MOOCs

A Review of the State-of-the-Art

Ahmed Mohamed Fahmy Yousef

1

, Mohamed Amine Chatti

1

, Ulrik Schroeder

1

Marold Wosnitza

2

and

Harald Jakobs

3

1

Learning Technologies Group (Informatik 9), RWTH-Aachen, Ahornstrasse 55, Aachen, Germany

2

School Pedagogy and Educational Research, RWTH-Aachen, Eilfschornsteinstraße 7, Aachen, Germany

3

Center for Innovative Learning Technologies (CIL), RWTH-Aachen, Ahornstrasse 55, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Massive Open Online Courses, MOOCs, OER, Learning Theories, Assessment.

Abstract: Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have drastically changed the way we learn as well as how we teach.

The main aim of MOOCs is to provide new opportunities to a massive number of learners to attend free

online courses from anywhere all over the world. MOOCs have unique features that make it an effective

technology-enhanced learning (TEL) model in higher education and beyond. The number of academic

publications around MOOCs has grown rapidly in the last few years. The purpose of this paper is to compile

and analyze the state-of-the-art in MOOC research that has been conducted in the past five years. A

template analysis was used to map the conducted research on MOOCs into seven dimensions, namely

concept, design, learning theories, case studies, business model, targets groups, and assessment. This

classification schema aims at providing a comprehensive overview for readers who are interested in

MOOCs to foster a common understanding of key concepts in this emerging field. The paper further

suggests new challenges and opportunities for future work in the area of MOOCs that will support

communication between researchers as they seek to address these challenges.

1 INTRODUCTION

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have

attracted a great deal of interest in educational

institutions. MOOCs anticipate leading the new

revolution of technology-enhanced learning (TEL),

by providing new opportunities to a massive number

of learners to attend free online courses from

anywhere all over the world (Liyanagunawardena et

al., 2013a). Over the last few years, the MOOCs

phenomenon has become widely acknowledged as

crucial for freely accessible high quality courses

provided by international institutes for informal as

well as formal education (Brown, 2013).

In recent years, topics around MOOCs are

widely discussed across a range of academic

publications from different theoretical and practical

perspectives, including numerous implementations

and design concepts of MOOCs. These publications

are however still in an infancy stage and a

systematic classification of the MOOC literature is

still missing. This paper is one of the efforts to:

1. Compile and analyze the state-of-the-art that has

been conducted on MOOCs between 2008 and

2013 to build a deep and better understanding of

key concepts in this emerging field.

2. Identify some future research opportunities in the

area of MOOCs that should be considered in the

development of MOOCs environments.

In the light of these goals, this paper will discuss

different angles of MOOCs and is structured as

follows: Section 2 is a review of the related work.

Section 3 describes the research methodology and

how we collected the research data. In section 4, we

review and discuss the state-of-the-art based on

several dimensions. Finally, Section 5 gives a

summary of the main findings of this paper and as a

result highlights new opportunities for future work.

2 RELATED WORK

Since research in MOOCs is still an emerging field,

we found only one systematic study of the published

9

Yousef A., Chatti M., Schroeder U., Wosnitza M. and Jakobs H..

MOOCs - A Review of the State-of-the-Art.

DOI: 10.5220/0004791400090020

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 9-20

ISBN: 978-989-758-022-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

literature of MOOCs from 2008-2012, done by

Liyanagunawardena et al. (2013b). The study

provides a quantitative analysis of 45 peer reviewed

studies and provides a general discussion based on a

categorization into eight dimensions, namely

introductory, concept, case studies, educational

theory, technology, participant focused, provider

focused, and other.

As compared to Liyanagunawardena et al.’s

study, our study adds a wide range of peer-reviewed

publications that have been conducted between 2008

and 2013 and provides a quantitative as well as

qualitative analysis of the MOOC literature.

Moreover, we apply a template analysis to

categorize the MOOCs state-of-the-art into several

dimensions. The study further provides critical

discussion according to each dimension and suggests

new opportunities for future research in MOOCs.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research was carried out in two main phases

including data collection followed by template

analysis of the literature review.

3.1 Data Collection

We collected data by applying the scientific research

method of identifying papers from internet resources

(Fink, 2005). This method includes three rounds.

Firstly, we searched 7 major refereed academic

databases

1

and secondly 18 academic journals

2

in the

field of education technology and e-learning indexed

by Journal Citation Reports (JCR), using the search

terms (and their plurals) “MOOC”, “Massive Open

1

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), JSTOR, ALT

Open Access Repository, Google Scholar, PsychInfo, ACM

publication, IEEEXplorer, and Wiley Online Library

2

American Journal of Distance Education, Australian Journal of

Educational Technology, British Journal of Educational

Technology, Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology,

Communications of the ACM, Continuing Higher Education

Review Journal, Educational Technology Research and

Development, Educational Theory, eLearning Papers Journal,

Frontiers of Language and Teaching, International Journal of

Innovation in Education, International Journal of Technology in

Teaching and Learning, International Review of Research in

Open and Distance Learning, Journal of Asynchronous

Learning Networks, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning,

Journal of Interactive Media in Education (JIME), Open Praxis

Journal, The European Journal of Open, and Distance and E-

Learning (EURODL)

Online Course” and “Massively Open Online

Course”. These two rounds resulted in 128 peer-

reviewed papers to be included in our study.

Thirdly, we applied a set of selection criteria as

follows:

1. Research must focus on MOOCs in pedagogical,

social, economic, and technical settings. Studies

with political and policymakers views were

excluded.

2. Papers providing experimental or empirical

studies from actual observations and case studies

with scientific data were included.

3. Papers presenting a new design of MOOCs were

included. Studies with personal opinions or

learner’s anecdotal impression were excluded.

The result was 84 peer-reviewed publications

which fit the criteria above (80 papers, 3

international reports, and 1 dissertation). Figure 1

shows the number of MOOCs publications between

2008 and 2013 which were found to be relevant for

this study.

Figure 1: MOOCs papers by publication year.

3.2 Template Analysis

The second phase was using Template Analysis as

classification technique for mapping MOOCs

literature in several dimensions (King, 2004). In the

first level of template analysis, we carefully read the

MOOCs literature to be familiar with the domain

context. Then, in the second level we formulated

concrete codes (themes), based on the understanding

of the studies domain and using the existing

classifications by Liyanagunawardena et al. (2013b)

and Pardos and Schneider (2013) as a reference to

test reliability and credibility. Then, we identified

seven codes as follows:

1. Concept included aspects in the literature which

referred to the concept e.g. definition, history,

and MOOCs types.

2. Design included design principals e.g.

pedagogical and technological features.

3. Learning theories that have built the theoretical

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Numberof

studies

1 1 3 8 11 60

0

20

40

60

80

MOOCsPublicationsbyyear

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

10

background of the conducted MOOC studies.

4. Case studies e.g. experimental and empirical

studies.

5. Business models that have been followed in the

different MOOC implementations.

6. Target groups included aspects which referred

to learner characteristics.

7. Assessment included different types in MOOCs

e.g. e-assessment, self-assessments, and peer-

assessment.

After having a stable code template, we had several

internal meetings to discuss each code and create a

mapping of the 84 publications that were selected in

this review into the seven identified codes as

depicted in Figure 2. This template analysis has been

done manually using printout tables.

Figure 2: Classification Map of MOOCs.

4 MOOC STATE-OF-THE-ART

In this section, we analyze and discuss in detail the

MOOCs state-of-the-art based on the template

analysis dimensions (codes) that have been

identified in Section 3. For the critical discussion

part, we apply the meta-analysis method which aims

to contrast and combine results from several studies

into a single scientific work (Fink, 2005).

4.1 Concept

The first dimension in our analysis is “concept”.

Nearly 25% of the literature reviewed in this paper

focus on the MOOC concept. To clarify the MOOC

concept three aspects have been considered in the

reviewed literature, namely definition, history, and

types.

4.1.1 MOOC Definition

Various definitions have been provided for the term

MOOC by describing the four words in the MOOC

acronym. The key elements of MOOCs are depicted

in Figure 3:

Massive(ly): In MOOCs, massiveness reflects

the number of course participants. While most of

the MOOCs had few hundred participants some

courses reached over 150,000 registrations

(Allen and Seaman, 2013); (Russell et al. 2013).

Massive refers to the capacity of the course to

expand to large numbers of learners (Anderson

and McGreal, 2012). The challenge is to find the

right balance between large number of

participants, content quality, and individual

needs of learners (Brown, 2013); (Esposito,

2012); (Laws et al., 2003).

Open: Openness includes four dimensions (4Rs)

Reuse, Revise, Remix, and Redistribute (Peter

and Deimann, 2013). In the context of MOOCs,

it refers to providing a learning experience to a

vast number of participants around the globe

regardless of their location, age, income,

ideology, and level of education, without any

entry requirements, or course fees to access high

quality education. Openness can also refer to

providing open educational resources (OER) e.g.

course notes, PowerPoint presentations, video

lectures, and assessment. (Anderson and

McGreal, 2012); (Schuwer et al., 2013).

Online: the term online refers to the accessibility

of these courses form each spot of the world via

internet connection to provide synchronous as

well as asynchronous interaction between the

course participants, (Brown, 2013); (Schuwer et

al., 2013). In some variations of MOOCs (e.g.

blended MOOCs), learners can learn at least in

part face-to-face beside the online interaction

possibilities (Stewart, 2013).

Courses: The term course is defined in higher

education as a unit of teaching. In MOOCs it

refers to the academic curriculum to be delivered

to the learners, including OER, learning

objectives, networking tools, assessments, and

learning analytics tools (Allen and Seaman,

2013); (Voss, 2013).

The original concept of MOOCs is to offer free and

open access courses for massive number of learners.

However, scalability issues and low completion

rates, (less than 10% in most of the offered MOOCs)

constantly concern the MOOC providers (Brown,

2013); (Trumbić and Daniel, 2013). Moreover,

20

16

15

15

8

5

5

Concept

Design

Learning

Theories

CaseStudy

Business

Models

Target

groups

Assessment

Classification Map of MOOCs

MOOCs-AReviewoftheState-of-the-Art

11

Figure 3: Key elements of MOOCs.

several MOOC providers either charge fees for their

courses or offer courses for free but learners have to

pay for exams, certificates, or teaching assistance

from third party partners (Brown, 2013). Thus, we

believe that the original definition of MOOCs will

change as a result of the various challenges and

rapid developments in this field.

4.1.2 MOOC History

Dave Cormier and Bryan Alexander coined the

acronym MOOC to describe the “Connectivism and

Connective Knowledge” (CCK08) course launched

by Stephen Downes and George Siemens at the

University of Manitoba in 2008 (Boven, 2013). This

new form of learning and teaching has led Stanford

University to offer three online courses in 2011

(Yuan and Powell, 2013a); (Rhoads, et al., 2013).

These courses significantly succeeded in attracting a

big number of participants, thus turning a qualitative

leap in the field of MOOCs. Driven by the success

of the Stanford MOOCs Sebastian Thrun and Peter

Norvig started to think about MOOC business

models and launched Udacity as a profit MOOC

model in 2012 (Peter and Deimann, 2013).

Two other Stanford professors Daphne Koller and

Figure 4: MOOCs and open education timeline (Yuan and

Powell, 2013a).

Andrew Ng have also started their own company

Coursera which partnered with dozens of renowned

universities to provide a platform for online courses

aiming at offering high quality education to

interested learners all over the world. (Schuwer, and

Janssen, 2013); (Dikeogu and Clark, 2013).

Additionally, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

(MIT) and Harvard University launched edX as a

non-profit MOOC platform. Figure 4 shows the

MOOC and open education timeline (Yuan and

Powell, 2013a).

Although these MOOCs platforms have different

objectives, they share the focus on building large

learning networks beyond the traditional teaching

environments.

4.1.3 MOOC Types

The current MOOC literature categorized MOOCs

into two main types “cMOOCs” and “xMOOCs”

(Smith and Eng, 2013). Moreover, new forms have

emerged from xMOOCs. These include “smOOCs”

and “bMOOCs”. Figure 5 shows the different types

of MOOCs and their underlying learning theories.

Figure 5: MOOC types.

The early MOOCs launched by Downes and

Siemens (CCK08) were driven by the connectivism

theory and were thus referred to as connectivist

MOOCs (cMOOCs). cMOOCs provide space for

self-organized learning where learners can define

their own objectives, present their own view, and

collaboratively create and share knowledge.

cMOOCs enable learners to build their own

networks via blogs, wikis, Google groups, Twitter,

Facebook, and other social networking tools outside

the learning platform without any restrictions from

the teacher (Kruiderink, 2013). Moreover, peer-

assessment was used to grade assignments or tests

based on pre-defined rubrics that improve students'

understanding of the content. Thus, cMOOCs are

distributed and networked learning environments

where learners are at the center of the learning

process. Figure 6 depicts the key concepts of

cMOOCs.

On the other hand, extension MOOCs

(xMOOCs) e.g. Coursera, edX, and Udacity follow

the behaviorism, cognitivist, and (social)

constructivism learning theories. In fact, in

xMOOCs, learning objectives are pre-defined by

Massive

• Large scale

100+ from

worldwide

Open

• Free of charge

• No requirements

•OER

Courses

• Learning

materials

• Assessment

• Networking tools

• Learning

analytics tools

Online

• Access at any

time around the

globe

• synchronous and

asynchronous

communication

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

12

Figure 6: cMOOCs.

teachers who impart their knowledge through short

video lectures, often followed by simple e-

assessment tasks (e.g. quiz, eTest) (Kruiderink,

2013); (Stewart, 2013); (Daniel, 2012). Only few

xMOOCs have used peer-assessment. Moreover,

xMOOCs provide limited communication space

between the course participants (Gaebel, 2013).

Unlike cMOOCs, the communication in xMOOCs

happens within the platform itself. The key concepts

of xMOOCs are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: xMOOCs.

Recently, new forms of MOOCs have emerged.

These include smOOCs as small open online courses

with a relatively small number of participants (e.g.

COER13) and blended MOOCs (bMOOCs) as

hybrid MOOCs including in-class and online

mediated instruction (e.g. OPCO11) with flexibility

ways that learners can interacting in real-time that fit

into around their motivation and to build learner

commitment to the courses (Coates, 2013); (Gaebel,

2013); (Daniel, 2012).

4.2 Design

The reviewed studies on MOOCs design distinguish

between pedagogical design principles that can

engage learners to attend the courses and

technological design principles that can make the

MOOCs more dynamic.

4.2.1 Pedagogical Design Principles

Most of the teachers and researchers believe that

MOOCs cannot completely replace traditional

learning (Ovaska, 2013). As a consequence, there is

an increasing focus on hybrid MOOCs (Szafir and

Mutlu, 2013). In order to encourage learners to

complete the course, Vihavainen, et al. (2012)

offered bMOOCs with support of scaffolding of

learner’s tasks using a purpose-built assessment

solution and continuous reflection between the

learner and the advisor. In other studies, the

integration of social networks in bMOOCs added

new value in learner’s interactions and activities

(Morris, 2013); (Calter, 2013).

McCallum, Thomas and Libarkin, (2013)

designed alphaMOOCs (aMOOCs) as a mix of

cMOOCs and xMOOCs by building collaboration

teams. McAndrew (2013) designed a project-based

MOOC (pMOOC) by structuring the offered MOOC

around a course-related project. Guàrdia, et al.

(2013) analyzed the learners needs in a MOOC and

presented a set of pedagogical design principles that

focus on improving the interactions among learners.

Bruff, et al (2013) discussed some pedagogical

design ideas that provide guidance on how to design

bMOOCs. The authors focused on competency-

based design, self-paced learning, pre-definition of

learning plans (objectives, schedules, and

assignments), as well as open network interaction

and collaboration tools that rise motivation and

avoid losing interest and drop out from the course.

And, Grünewald, et al. (2013) suggested peer-

assistance through the course to solve learning

difficulties.

4.2.2 Technological Design Principles

MOOCs are include several technology features that

support different important activities in the learning

experience such as interaction, collaboration,

evaluation, and self-reflection (de Waard et al.,

2011b); (Fournier et al., 2011). The tools used in the

reviewed literature can be classified into three main

categories, namely collaboration, assessment, and

analytics tools.

Most of the MOOCs provide collaboration work

spaces that include several tools to support learners

in communicating with each other such as forums,

blogs, video podcasts, social networks, and

dashboards (McAndrew, 2013); (Mak et al., 2010).

Different e-assessment methods are applied in

MOOCs. While most of xMOOCs use traditional

forms of e-assessment like eTests and Quizzes,

MOOCs-AReviewoftheState-of-the-Art

13

cMOOCs rather focus on self-assessment and peer-

assessment (Kellogg, 2013); (Spector, 2013).

In MOOCs it is difficult to provide personal

feedback to a massive number of learners. Thus,

several MOOC studies tried to apply learning

analytics tools to monitor the learning process,

identify difficulties, discover learning patterns,

provide feedback, and support learners in reflecting

on their own learning experience (Fournier et al.,

2011); (Giannakos et al. 2013).

4.3 Learning Theories

How learners learn through MOOCs? In other

words, how they absorb, process, build, and

construct knowledge? This is a simple question, but

the answer is quite complicated. Behaviorists and

cognitivists believe that learning experience is a

result of the human action with the learning

environment (Kop and Hill, 2008). Constructivists,

by contrast, believe that learning is an active process

of creating meaning from different experiences and

that learners learn better by doing (Anderson and

Dron, 2011). In the last years, technology has

changed the way we learn as well as we teach

(Viswanathan, 2013). And, the social Web has

provided new ways how we network and learn

outside the classroom. These opportunities are

reflected in recent learning theories and models.

These include connectivism which views learning as

a network-forming process (Martin, 2013);

(Tschofen and Mackness, 2012); (Kop, 2011);

(Siemens, 2005) and the Learning as a Network

(LaaN) theory which starts from the learner and

views learning as a continuous creation of a personal

knowledge network (PKN) (Chatti, 2010).

Back to the main question how learners learn

through MOOCs? As discussed in Section 4,

MOOCs are running in two major categories:

cMOOCs and xMOOCs. CCK08 was the first

MOOC designed based on the principals of

connectivism (Kop et al., 2011). The aim of CCK08

– and other cMOOCs – is to build and construct

knowledge through the interaction in learner

networks (Cabiria, 2012); (Bell, 2011); (Chamberlin

and Parish, 2011). Rodriguez (2013) pointed out that

some cMOOCs indeed succeeded to improve the

learner’s motivation. On the other hand, xMOOCs

were based on the behaviorism and cognitivism

theories with some (social) constructivism

components that focus on learning by doing (i.e.

experimental, project-based, or task-based)

activities. This wave of MOOCs is similar to the

traditional instructor-led courses offered at

universities that are organized around video lectures,

and e-assessment. Most of the researchers in the

reviewed literature put a heavier focus on xMOOCs

as a new model of learning and teaching in higher

education (Milligan et al., 2013); (Rodriguez, 2012).

Few researchers stressed the importance of social

components in xMOOCs. Blom et al. (2013)

reported that xMOOCs become more social using

collaboration tools e.g. forums and wikis. Purser et

al., (2012) suggested that the idea of peer-to-peer in

collaborative learning helps learners to improve their

learning outcome in xMOOCs.

In general, cMOOCs reflect the new learning

environments characterized by flexibility and

openness. On the other hand, xMOOCs offer high

quality content as compared to cMOOCs. To fill this

gap, hybrid MOOCs bMOOCs have been proposed

to combine the advantages of both cMOOCs and

xMOOCs.

4.4 Case Studies

Several case studies of MOOCs have been discussed

in the reviewed literature. In Table 1, we compare

different case studies in terms of learning theories,

design elements, structure, tools, and assessment

(Malan, 2013). We selected six case studies that are

representatives for different MOOC types. To

represent cMOOCs we selected CCK08 (Rodriguez,

2013); (Bell, 2010); (Mackness et al., 2010); (Fini,

2009). From xMOOCs we selected edX as non-

profit platform and Coursera as profit platform

(Cooper and Sahami, 2013); (Portmess, 2013);

(Rodriguez, 2013); (Subbian, 2013); (Machun et al.,

2012); (Hoyos et al., 2013). In addition, we selected

OPCO11 as an example of bMOOCs and COER13

and MobiMOOC as examples of smOOCs (Arnold,

2012); (de Waard et al., 2011a); (Romero, 2013);

(Koutropoulos, et al., 2012).

These different MOOCs share some common

features that focus on video-based lectures, the

support of open registration and informal learning,

and the use of social tools. Most of the MOOCs

apply traditional e-assessment tools (e.g. E-Tests,

Quizzes, MCQ). Peer-assessment is mainly used in

cMOOCs and bMOOCs and self-assessment rather

in smOOCs. The majority of the reviewed case

studies implement the behaviorism, cognitivism, and

constructivism learning theories. Only few case

studies (e.g. CCK08 and MobiMOOC) include

elements that are borrowed from connectivism, such

as personal learning environments and open

networking.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

14

Table 1: Comparison of MOOCs case studies.

Compare Item

CCK08

edX

Coursera

OPCO11

COER13

MobiMOOC

Learning theory

Connectivism

√ - - - - (√)

Behaviorism

- √ √ - - -

Cognitivist

- √ √ - - (√)

Social

constructivism

- - - √ √ -

Assessment

E-Assessment

(√) √ √ √ √ √

Peer-Assessment

√ - (√) (√) - -

Self-Assessment

- - - - (√) (√)

Openness

Profit

- - √

- - -

Open registration

√ √ √ √ √ √

Download

Material

- √ (√) (√) (√) √

Form

Formal Learning

(√) - (√) (√) - -

Informal Learning

√ √ √ √ √ √

Learning Tools

Video Lecture

√ √ √ √ √ √

Face-to-Face

- - - √ - -

Blogs, forums,

social network

√ √ √ √ √ √

Lecture Note, PPT

and PDF

√ √ √ √ √ √

√ Completely (√) Partly - Not supported

4.5 Business Models

The initial vision of MOOCs was to provide open

online courses that could reduce the cost of

university-level education and reach thousands of

low-income learners (Teplechuk, 2013); (Cusumano,

2013). Nevertheless, new business models have been

launched e.g. in Coursera, Udacity, and Udemy.

These business models are heralding a change in the

education landscape that poses a threat to the quality

of learning outcome and future educational

pathways (Schuwer and Janssen, 2013); (Yuan, and

Powell, 2013b).

Due to the huge budget that has been spent to

develop MOOC platforms, MOOC providers are

fighting to come up with new business models to

satisfy their investors (Freeman and Hancock, 2013);

(Guthrie et al, 2013).

Ruth (2012) reported his overview of potential

business models such as offering courses for free

and learners pay for certification, examination, and

teaching assistance. Coursera, for instance, offers

additional examinations for certificates. The

question here is whether these certificates will be

accepted. Green (2013) believes that if the

universities provide MOOC credits, this will be a

potential route to accept these certificates in the real

market. To achieve this, MOOCs should meet the

market needs by providing high quality content as

well as high quality outcome (Lambert and Carter,

2013); (Gallagher and LaBrie, 2012).

4.6 Target Groups

Some demographics studies have been conducted to

analyze target groups in MOOCs by determining

their locations, age group, and learner patterns.

One major goal of MOOCs was to reach low-

income learners particularly in developing countries.

Studies, however, have shown that the vast majority

of MOOC participants were from North America

and Europe. Only few participate from South East

Asia and fewer from Asia and Africa (Clow, 2013);

(Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013a); (Stine, 2013).

This is consistent with the analysis of 2.9 million

participants registered in Coursera from 220

countries around the globe (Waldrop, 2013).

Possible obstacles that could prevent learners

from Africa and Asia to take part in MOOCs include

the poor technology infrastructure. Only 25% of

Africa has electricity access (WEO-2012). And

Africa has the lowest internet access all over the

world with only 7% (Sanou, 2013). Asia is a

continent with many different cultures and

languages. Thus, linguistic issues could be a barrier

to participate in MOOCs.

Stine (2013) and de Waard et al. (2011b) noted

that around 50% of the participants from 31-50 age

groups, which indicates that informal learners have

more interest in MOOCs.

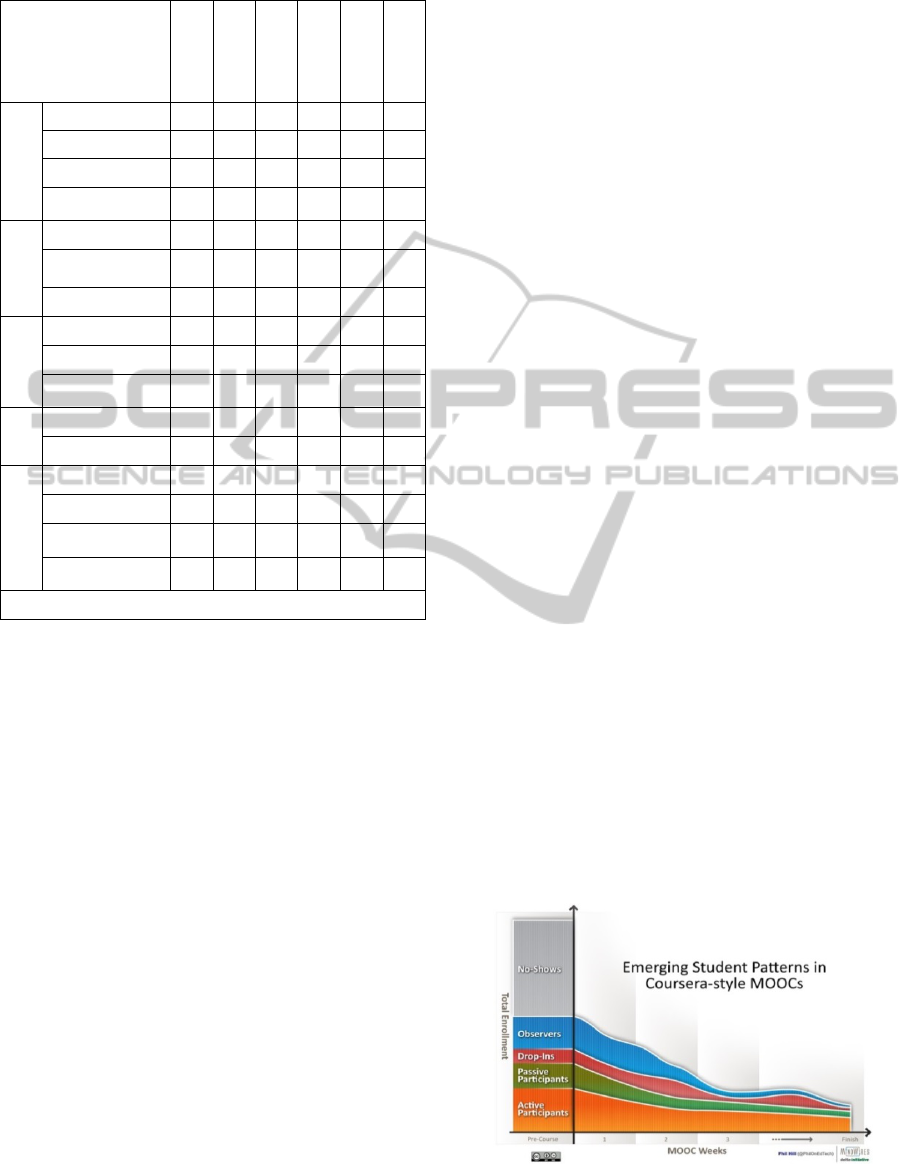

Several studies have reported a high drop-out

rate that reflects the learner patterns in MOOCs

(Waite, et al., 2013). Hill (2013) identified five

patterns of participants in Coursera, as shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 8: Pattern of participants in Coursera (Hill, 2013).

MOOCs-AReviewoftheState-of-the-Art

15

The vast majority were No-Shows participants

who register but never log into the course. Secondly,

observers who read content or discussions without

submitting any assignments. Thirdly, Drop-ins

participants who are doing some activities but do not

complete the course. Fourthly, Passive participants

who take the course and do tests but do not

participate in the discussion. Fifthly, Active

participants who regularly do all assignments and

actively take part in the discussions.

Some studies explored pedagogical approaches

to engage Observers, Drop-ins, and Passive

participants to be active learners through e.g. game-

based learning (Romero, 2013), social networking

that help learners to create their own personal

learning environments (Guàrdia, et al., 2013), and

project-based learning (Irvine et al, 2013);

(McAndrew, 2013).

4.7 Assessment

The ability to evaluate vast number of learners in

MOOCs is indeed a big challenge (Yin and

Kawachi, 2013). Thus, assessment is an important

factor for the future success of MOOC. So far

MOOC providers didn’t offer official academic

accreditation from their home institutions, which

might indicate that the quality of learning outcome

in MOOCs is different from university courses

(Sandeen, 2013); (Gallagher and LaBrie, 2012).

Currently, MOOCs are only providing a non-credit

certificate e.g. completion, attendance, or

participation certificate. In the reviewed literature,

three main types of assessment were conducted in

MOOCs, namely e-assessment, peer-assessment, and

self-assessment.

4.7.1 e-Assessment

e-Assessment is often used in xMOOCs to gauge

student performance. E-assessment in xMOOCs is

restricted to closed question formats. These include

exams with multiple choice questions based on

machine grading (Conrad, 2013). This

implementation of assessment is applicable in

Science courses. It is, however difficult to apply e-

assessment in Humanities courses due the nature of

these courses which are based on the creativity and

imagination of the learners (Sandeen, 2013).

4.7.2 Peer-assessment

Peer-assessment was used in cMOOCs and

xMOOCs to review essays, projects, and team

assignments. These assignments are not graded

automatically, but learners themselves can evaluate

and provide feedback on each other’s work. This

method of assessment is suitable in Humanities,

Social Sciences and Business studies, which do not

have clear right or wrong answers (O’Toole, 2013).

Cooper and Sahami (2013) point out that, some

learners in peer-assessment grade without reading

the work to be reviewed or do not follow a clear

grading scheme, which negatively impacts the

quality of the given feedback. Therefore, more

criteria and indicators are needed to ensure that peer-

assessment is effective.

4.7.3 Self-assessment

Self-assessment is still not widely used in MOOCs.

Sandeen (2013) and Piech et al. (2013) identified

some self-assessment techniques. These include

model answer as tool to students to cross check if

the marks they scored are in tune with the model

answers set by the educators, and learning analytics

where the learners can self-reflect on their

achievements.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

MOOCs present an emerging branch of online

learning that is gaining interest in the technology-

enhanced learning (TEL) community. In the last few

years after the launch of the first MOOC in 2008, a

considerable number of research studies have been

conducted to explore the potential of MOOCs to

improve the effectiveness of the learning experience.

The main aim of this paper was to compile and

analyze the state-of-the-art in MOOC research that

has been conducted in the past five years. 84 peer

reviewed papers were selected in this study. A

template analysis was applied to analyze and

categorize the MOOCs literature into 7 dimensions,

namely concept, design, learning theories, case

studies, business models, target groups, and

assessment.

The main result of our study is that the initial

vision of MOOCs as a new learning environment

that aims at breaking down obstacles to learning for

anyone, anywhere and at any time around the globe

is far away from the reality. In fact, most MOOC

implementations so far still follow a top-down,

controlled, teacher-centered, and centralized

learning model. Attempts to implement bottom-up,

student-centered, really open, and distributed forms

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

16

of MOOCs are rather the exception rather than the

rule. In general, MOOCs further require key

stakeholders to address a number of challenges,

including questions about hybrid education, role of

the university/teacher, plagiarism, certification,

completion rates, and innovation beyond traditional

learning models. These challenges will need to be

addressed as the understanding of the technical and

pedagogical issues surrounding MOOCs evolves. In

the following, we suggest research opportunities in

relation to each dimension:

Concept: More theoretical work is needed to

achieve a common understanding of the MOOC

concept as well as a systematic mapping between

the course goals and the MOOC type to be

implemented.

Design: it is necessary to conduct research on how

to improve the MOOC environments by

investigating new learning models (e.g.

personalized learning, project-based learning,

game-based learning, inquiry-based learning) and

tools (e.g. learning analytics).

Learning Theories: It is crucial that future MOOC

implementations are backed by a solid theoretical

background. A heavier focus should be put on

cMOOCs as well as bMOOCs which have the

potential to support different learning models

beyond formal institutional learning. These include

informal learning, personalized learning,

professional learning, and lifelong learning.

Case Studies: The field of MOOCs is emerging

and it is needed to conduct and share more

experimental studies with different MOOC formats

and variations.

Business Models: We need to identify new ways to

think about business models that preserve the

quality of the learning experience supported by

MOOCs.

Target Groups: We need to investigate new

methods to increase the motivation of observers,

drop-ins and passive learners in MOOCs through

e.g. learning analytics.

Assessment: it is necessary to go beyond

traditional e-assessment methods and apply open

assessment methods that fit better to the MOOC

environments characterized by openness,

networking, and self-organization.

This paper which compiles and analyzes the state-of-

the-art in MOOC research is original because firstly

it provides a comprehensive review of the

development of MOOCs which have been lacking

until now and secondly it examines the context

within which further work can take place by

identifying key challenges and opportunities that lie

ahead in this emerging research area.

Our future work will focus on learner-centered

MOOCs by providing a MOOC platform where

learners can take an active role in the management

of their learning environments, through self-

organized dashboards and collaborative workspaces.

The platform will be based on an app system that

enables learners to select the apps according to their

needs and preferences. These include a collaborative

video annotation app as well as learning analytics

apps to support self-reflection, awareness, and self-

assessment.

REFERENCES

Allen, I. E. and Seaman, J. (2013). Changing Course: ten

years of tracking online education in the United States.

Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research

Group, LLC, annual report, Retrieved from

http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/changin

gcourse.pdf.

Anderson, T., and Dron, J. (2011). Three generations of

distance education pedagogy. International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3), pp.

80-97.

Anderson, T., and McGreal, R. (2012). Disruptive

pedagogies and technologies in universities. Education

Technology and Society, 15(4), pp. 380-389.

Arnold, P. (2012). Open educational resources: The way

to go, or “Mission Impossible” in (German) higher

education? In Stillman, Larry; Denision, Tom;

Sabiescu, Amalia; Memarovic, Nemanja (Ed.) (2012):

CIRN 2012 Community Informatics Conference.

Bell, F. (2010). Network theories for technology-enabled

learning and social change: Connectivism and actor

network theory. Proceedings of the Seventh

International Conference on Networked Learning

2010, pp. 526-533.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its place in theory-

informed research and innovation in technology-

enabled learning. The International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3), pp.

98-118.

Blom, J., Verma, H., Li, N., Skevi, A., and Dillenbourg,

P. (2013). MOOCs are more social than you believe.

eLearning Papers, ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

Boven, D. T. (2013). The next game changer: the

historical antecedents of the MOOC movement in

education. eLearning Papers, ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue

33.

Brown, S. (2013). Back to the future with MOOCs?.

ICICTE 2013 Proceedings, pp. 237-246.

Bruff, D. O., Fisher, D. H., McEwen, K. E., and Smith, B.

E. (2013). Wrapping a MOOC: Student perceptions of

an experiment in blended learning, Journal of Online

Learning and Teaching, 9(2), pp. 187-199.

MOOCs-AReviewoftheState-of-the-Art

17

Cabiria, J. (2012). Connectivist learning environments:

Massive open online courses. The 2012 World

Congress in Computer Science Computer Engineering

and Applied Computing, Las Vagas.

Calter, M. (2013). MOOCs and the library: Engaging with

evolving pedagogy. IFLA World Library and

Information Congress (IFLA WLIC 2013), Singapore.

Chamberlin, L., and Parish, T. (2011). MOOCs: Massive

Open Online Courses or Massive and Often Obtuse

Courses?. eLearn, 2011(8), 1.

Chatti, M. A. (2010). Personalization in Technology

Enhanced Learning: A Social Software Perspective.

Shaker Verlag, November 2010, Dissertation, RWTH

Aachen University.

Clow, D. (2013). MOOCs and the funnel of participation.

LAK '13, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 185-189.

Coates, K. (2013). The re-invention of the academy: How

technologically mediated learning will –and will not –

transform advanced education. 6th International

Conference, ICHL 2013 Toronto, ON, Canada.

Springer, pp.1-9.

Conrad, D. (2013). Assessment challenges in open

learning: Way-finding, fork in the road, or end of the

line?. Open Praxis, 5 (1), pp. 41-47.

Cooper, S., and Sahami, M. (2013). Reflections on

Stanford’s MOOCs :New possibilities in online

education create new challenges. Comm. ACM 56(2),

pp. 28–30.

Cusumano, M. A. (2013). Technology strategy and

management: Are the costs of ‘free’ too high in online

education? Comm. ACM 56(4), pp. 26–29.

Daniel, J. (2012). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a

maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of

Interactive Media in Education, Retrieved from

http://www.jime.open.ac.uk/jime/article/viewArticle/2

012-18/html.

de Waard, I., Abajian, S., Gallagher, M. S., Hogue, R.,

Keskin, N., Koutropoulos, A., and Rodriguez, O. C.

(2011b). Using mLearning and MOOCs to understand

chaos, emergence, and complexity in education.

International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning, 12(7), pp. 94-115.

de Waard, I., Koutropoulos, A., Keskin, N. Ö., Abajian, S.

C., Hogue, R., Rodriguez, C. O., and Gallagher, M. S.

(2011a). Exploring the MOOC format as a

pedagogical approach for mLearning. 10th World

Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning

(mLearn2011). Beijing, China.

Dikeogu, G. C. and Clark, C. (2013). Are you MOOC-ing

yet? A review for academic libraries. College &

University Libraries Section Proceedings (CULS), 3,

pp. 9-13.

Esposito, A. (2012). Research ethics in emerging forms of

online learning: issues arising from a hypothetical

study on a MOOC. The Electronic Journal of e-

Learning, 10(3) pp. 315-325.

Fini, A. (2009). The technological dimension of a massive

open online course: The Case of the CCK08 course

tools. The International Review of Research in Open

and Distance Learning, 10(5).

Fink, A. (2005). Conducting research literature reviews:

from the internet to paper (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks,

California: Sage Publications.

Fournier, H., Kop, R., and Sitlia, H. (2011). The value of

learning analytics to networked learning on a personal

learning environment. LAK '11 Proceedings of the 1st

International Conference on Learning Analytics and

Knowledge, pp. 104-109.

Freeman, M., and Hancock, P. (2013). Milking MOOCs:

Towards the right blend in accounting education. In

The Virtual University: Impact on Australian

Accounting and Business Education, part B, pp. 86-

100.

Gaebel, M. (2013). MOOCs Massive Open Online

Courses. EUA Occasional papers, Retrieved from

http://www.eua.be/Home.aspx.

Gallagher, S. and LaBrie, J. (2012). Online learning 2.0:

strategies for a mature market. Continuing Higher

Education Review, 76, pp. 65-73.

Giannakos, M. N., Chorianopoulos, K., Ronchetti, M.,

Szegedi, P. and Teasley, S. D. (2013). Analytics on

video-based learning. LAK '13, Leuven, Belgium, pp.

283-284.

Green, K. (2013). Mission, MOOCs & money. AGB,

Trusteeship Magazine, 21(1), pp. 9-15.

Grünewald, F., Meinel, C., Totschnig, M., and Willems,

C. (2013). Designing MOOCs for the support of

multiple learning styles. 8th European Conference on

Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2013.

Pathos, Cyprus, pp. 371-382.

Guàrdia, L., Maina, M., and Sangrà, A. (2013). MOOC

Design Principles. A Pedagogical Approach from the

Learner’s Perspective. eLearning Papers, ISSN: 1887-

1542, Issue 33.

Guthrie, J., Burritt, R., and Evans, E. (2013). Challenges

for accounting and business education: blending

online and traditional universities in a MOOC

environment. In The Virtual University: Impact on

Australian Accounting and Business Education, part

one pp.9-22.

Hill, P. (2013). Some validation of MOOC student

patterns graphic. Retrieved from

http://mfeldstein.com/validation-mooc-student-

patterns-graphic/

Hoyos, C. A., Sanagustín, M. P., Kloos, C. D., Parada G.,

H. A., Organero, M. M., and Heras, A. R. (2013).

Analysing the Impact of Built-In and External Social

Tools in a MOOC on Educational Technologies. 8th

European Conference on Technology Enhanced

Learning, EC-TEL2013, Paphos, Cyprus, Springer, pp.

5-18.

Irvine, V., Code, J., and Richards, L. (2013). Realigning

higher education for the 21st-century learner through

multi-access learning. Journal of Online Learning and

Teaching, 9(2), pp. 172-186.

Kellogg, S. (2013). How to make a MOOC. Nature,

international weekly journal of science, Macmillan

Publishers Limited, 499, pp. 369-371.

King, N. (2004) Using Templates in the Thematic

Analysis of Text. In C.Cassell and G.Symon (Eds.),

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

18

Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in

Organizational Research, Sage Publications: 256–270.

Kop, R. (2011). The challenges to connectivist learning on

open online networks: Learning experiences during a

massive open online course. The International Review

of Research in Open and Distance Learning, Special

Issue-Connectivism: Design and Delivery of Social

Networked Learning, 12(3), pp. 19-38.

Kop, R., and Hill, A. (2008). Connectivism: Learning

theory of the future or vestige of the past?.

International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning, 9(3).

Kop, R., Fournier, H., and Mak, J. S. F. (2011). A

pedagogy of sbundance or a pedagogy to support

human beings? Participant support on Massive Open

Online Courses. The International Review of Research

in Open and Distance Learning, Special Issue -

Emergent Learning, Connections, Design for

Learning, 12(7): pp. 74-93.

Koutropoulos, A., Gallagher, M. S., Abajian, S. C., de

Waard, I., Hogue, R. J., Keskin, N. Ö., and Rodriguez,

C. O. (2012). Emotive vocabulary in MOOCs: Context

& participant retention. European Journal of Open,

Distance and E-Learning.

Kruiderink, N. (2013). Open buffet of higher education. In

Trend report: open educational resources 2013, pp.

54-58.

Lambert, S., and Carter, A. (2013). Business Models for

the Virtual University. In The Virtual University:

Impact on Australian Accounting and Business

Education, Part B, pp.77-85.

Laws, R. D., Howell, S. L., and Lindsay, N. K. (2003).

Scalability in Distance Education: Can We Have Our

Cake and Eat it Too?. Online Journal of Distance

Learning Administration, 6(4).

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A., and Williams,

S. A. (2013b) MOOCs: A systematic study of the

published literature 2008-2012. The International

Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning,

14(3): pp. 202-227.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Williams, S., and Adams, A.

(2013a).The impact and reach of MOOCs: A

developing countries’ perspective. eLearning Papers,

ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

Machun, P. A., Trau, C., Zaid, N., Wang, M., and Ng, J.

W. (2012). MOOCs: Is there an app for that?:

expanding Mobilegogy through an analysis of

MOOCs and iTunes university. International

Conferences on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent

Technology, IEEE/WIC/ACM, pp. 321-325.

Mackness, J. Mak, S. F. J., and Roy Williams, R. (2010).

The ideals and reality of participating in a MOOC. 7th

International Conference on Networked Learning

2010 Proceedings, pp. 266-274.

Mak, S. F. J., Williams, R. and Mackness, J. (2010). Blogs

and forums as communication and learning tools in a

MOOC. In L. Dirckinck–Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, C.

Jones, M. de Laat, D. McConnell, & T. Ryberg (Eds.),

Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference

on Networked Learning 2010, pp. 275-284.

Malan, D. J. (2013). Implementing a Massive Open Online

Course (MOOC). Journal of Computing Sciences in

Colleges, 28(6), pp. 136-137.

Martin, F. (2013). Will Massive Open Online Courses

change how we teach?: sharing recent experiences

with an online course. Comm. ACM 55(8), pp. 26–28.

McAndrew, P. (2013). Learning from open design:

running a learning design MOOC. eLearning Papers,

ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

McCallum, C. M., Thomas, S. and Libarkin, J. (2013). The

AlphaMOOC: Building a Massive Open Online

Course one graduate student at a time. eLearning

Papers, ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

Milligan, C., Littlejohn, A., and Margaryan, A. (2013).

Patterns of engagement in connectivist MOOCs.

Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), pp.

149-159.

Morris, L. V. (2013) MOOCs, emerging technologies, and

quality. Innovative Higher Education, Springer, 38,

pp. 251-252.

O'Toole, R. (2013) Pedagogical strategies and

technologies for peer assessment in Massively Open

Online Courses (MOOCs). Discussion Paper.

University of Warwick, Coventry, UK: University of

Warwick. Retrieved from

http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/54602/

Ovaska, S. (2013). User experience and learning

experience in online HCI courses. In P. Kotzé et al.

(Eds.): INTERACT 2013, Part IV, LNCS 8120,pp.

447-454.

Pardos, Z. A. and Schneider, E. (2013). First annual

workshop on Massive Open Online Courses

(moocshop). In K. Yacef et al. (Eds.): AIED, LNAI.

Springer 7926, P. 950.

Peter, S. and Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness

in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis,

5(1), pp. 7-14.

Piech, C., Huang, J., Chen, Z., Do, C., Ng, A., and Koller,

D. (2013). Stanford University, Retrieved from

http://www.stanford.edu/~cpiech/bio/papers/tuningPee

rGrading.pdf.

Portmess, L. (2013). Mobile Knowledge, karma points and

digital Peers: The tacit epistemology and linguistic

representation of MOOCs. Canadian Journal of

Learning and Technology, 39(2).

Purser, E., Towndrow, A., and Aranguiz, A. (2013).

Realising the potential of peer-to-peer learning: taming

a MOOC with social media. eLearning Papers, ISSN:

1887-1542, Issue 33.

Rhoads, R. A., Berdan, J. and Lindsey, B. T. (2013). The

open courseware movement in higher education:

unmasking power and raising questions about the

movement's democratic potential. Educational Theory,

63(1), pp. 87-110.

Rodriguez, C. O. (2012). MOOCs and the AI-Stanford like

courses: Two successful and distinct course formats

for massive open online courses. European Journal of

Open, Distance and E-Learning.

Rodriguez, O. (2013). The concept of openness behind c

and x-MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). Open

MOOCs-AReviewoftheState-of-the-Art

19

Praxis, Special theme: Openness in higher education,

5(1), pp. 67-73.

Romero, M. (2013). Game based learning MOOC.

promoting entrepreneurship education. eLearning

Papers, ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

Russell, D. M., Klemmer, S., Fox, A., Latulipe, C.,

Duneier, M., & Losh, E. (2013, April). Will massive

online open courses (moocs) change education?. In

CHI'13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (pp. 2395-2398). ACM..

Ruth, S. (2012). Can MOOC’s and existing e-learning

paradigms help reduce college costs? International

Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning,

8(1), pp. 21-32.

Sandeen, C. (2013). Assessment’s place in the new

MOOC world. Research & Practice in Assessment

Journal, 8 (summer 2013), pp. 5-13.

Sanou, B. (2013). The World in 2013: ICT Facts and

Figures. International Telecommunications Union.

Schuwer, R. and Janssen, B. (2013). Trends in business

models for open educational resources and open

education. In Trend report: open educational

resources 2013, pp. 60-66.

Schuwer, R., Janssen, B. and Valkenburg, W. V. (2013).

MOOCs: trends and opportunities for higher

education. In Trend report: open educational

resources 2013, pp. 22-27.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for

the Digital Age. International Journal of Instructional

Technology and Distance Learning, 2 (1).

Smith, B. and Eng, M. 2013. (2013). MOOCs: A learning

journey two continuing education practitioners

investigate and compare cMOOC and xMOOC

learning models and experiences. 6th International

Conference, ICHL 2013 Toronto, ON, Canada.

Springer, pp.244-255.

Spector, J. M. (2013). Trends and research issues in

educational technology. The Malaysian Online

Journal of Educational Technology, 1 (3), pp. 1-9.

Stewart, B. (2013). Massiveness + Openness = new

literacies of participation?. Journal of Online Learning

and Teaching, 9(2), pp. 228-238.

Stine, J. K. (2013). MOOCs and executive education.

UNICON, research report. Retrieved from

http://uniconexed.org/2013/research/UNICON-Stine-

Research-06-2013-final.pdf.

Subbian, V. (2013). Role of MOOCs in integrated STEM

education: A Learning perspective. 3rd IEEE

Integrated STEM Education Conference.

Szafir, D. and Mutlu, B. (2013). ARTFuL: Adaptive

review technology for flipped learning. In CHI 2013

conference: Changing Perspectives, Paris, France, pp.

1001-1010.

Teplechuk, E. (2013). Emergent models of Massive Open

Online Courses: an exploration of sustainable practices

for MOOC institutions in the context of the launch of

MOOCs at the University of Edinburgh. MBA

Dissertation, University of Edinburgh.

Trumbić, S. U. and Daniel, J. (2013). Making sense of

MOOCs: The evolution of online learning in higher

education. 8th European Conference on Technology

Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2013, Paphos, Cyprus,

pp.1-4.

Tschofen, C., Mackness, J. (2012). Connectivism and

dimensions of individual experience. The

International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning, 13 (1), pp. 124-143.

Vihavainen, A., Luukkainen, M. and Kurhila, J. (2012).

Multi-faceted support for MOOC in programming.

SIGITE’12, Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest

Group for Information Technology Education

Conference, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, pp. 171-176.

Viswanathan, R. (2013). Teaching and learning through

MOOC. Frontiers of Language and Teaching, 3, pp.

32-40.

Voss, B. D. (2013). Massive Open Online Courses

(MOOCs): A primer for university and College Board

members. AGB Association of Governing Boards of

Universities and Colleges.

Waite, M., Mackness, J., Roberts, G., and Lovegrove, E.

(2013). Liminal participants and skilled orienteers:

Learner participation in a MOOC for new lecturers.

Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), pp.

200-215.

Waldrop, M. M. (2013). Online learning: Campus 2.0.

Nature, international weekly journal of science,

Macmillan Publishers Limited, 495, pp. 160-163.

WEO (2012). International enargy agency. Retrieved from

http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/

Yin, S., and Kawachi, P. (2013). Improving open access

through prior learning assessment. Open Praxis, 5 (1),

pp. 59-65.

Yuan, L. and Powell, S. (2013a). MOOCs and open

education: Implications for higher education. JISC

CETIS, Retrieved from http://jisc.cetis.ac.uk/

Yuan, L., and Powell, S. (2013b). MOOCs and disruptive

innovation: Implications for higher education,

eLearning Papers, ISSN: 1887-1542, Issue 33.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

20