Synchronization of Electroencephalography and Eye Tracking using

Global Illumination Changes

Daniel Siboska, Henrik Karstoft and Henrik Pedersen

Department of Engineering, Aarhus University, Finlandsgade 22, 8200 Aarhus N, Denmark

Keywords: Electroencephalography, Eye Tracking, Gaze Estimation, Synchronization.

Abstract: This paper describes a flexible method for synchronizing electroencephalography (EEG) and eye tracking

(ET) recordings to the presentation of visual stimuli. The method consists of embedding a synchronization

signal in the visual stimuli, and recording this signal with both the EEG and ET equipment. The signal is

recorded by the EEG device as an additional data channel, and with the camera used in the ET equipment by

modulating the global illumination of the scene in time with the synchronizing signal. The prototype system

where this method was implemented resulted in a single sample of jitter in both the EEG and ET system,

while the ET system achieved a spatial resolution of 1.26 degrees. The system will be used in future work

with augmented memory applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recording of brain activity through

electroencephalography (EEG) combined with

measurements of eye movements gives researchers a

powerful tool for analyzing the human visual system

(HVS) (Sereno 2003). Such tools have been used for

developing methods for enhancing the everyday life

of severely disabled people, who have no other

means of communication than modulating their eye

movement and brain wave patterns (Y. Wang et al.

2008), (Agustin 2009). Applications for ordinary

users, such as image searching and classification, are

emerging as well (J. Wang et al. 2009), (E. a

Pohlmeyer et al. 2011), and the combination of eye

tracking (ET) and EEG recording holds promise as

one of the fundamental technologies in developing

augmented memory applications (Davies 2011),

(Bell & Gemmell 2007) in the near future.

Multiple researchers (Plöchl et al. 2012),

(Görgen & Walter 2010) have set up EEG/ET-

systems where the visual stimuli is presented on a

computer display, the eye movements are measured

with a video-based eye tracker, and the EEG is

recorded with a digital recording device connected

to a computer. The synchronization of these signals

(stimuli, EEG, and eye movement) is of profound

importance if any causality between the stimuli and

the response is to be analyzed, and is a major

challenge.

This challenge is addressed by the authors in

(Görgen & Walter 2010) who use accurate control of

the timing of the appearance of each frame of stimuli

on the monitor and of the recording of each sample

from the eye tracker and EEG to achieve

synchronization of the stimuli, EEG and eye

movement. This strategy requires low level control

of the graphics hardware, as well as a special

purpose video recording device for the eye tracker.

In commercial state of the art systems such as the

RED500 with EEG headset from SensoMotoric

Instruments GmbH (SMI) and Emotiv, or the Smart

Eye Pro from Electrical Geodesics Inc. (EGI) and

Smart Eye AB, a similar low level control of the

sampling time of both EEG and ET is used.

In this article we propose an alternative strategy

for solving the synchronization issue in an EEG/ET-

system. We embed a synchronization signal in the

visual stimuli and record this signal with both the

eye tracker and EEG recording device. This offers

greater freedom in the choice of stimulus display

and video recording equipment for eye tracking, and

enables a more flexible generation of stimuli,

without the strict need for low level hardware

programming. Hereby already available hardware

can be used when a researcher wants access to a

combined EEG/ET system, instead of having to

acquire new hardware.

The following section describes the hardware

and software algorithms used in the combined

EEG/ET setup. Subsequently we evaluate the

55

Siboska D., Karstoft H. and Pedersen H..

Synchronization of Electroencephalography and Eye Tracking using Global Illumination Changes.

DOI: 10.5220/0004800400550060

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing (BIOSIGNALS-2014), pages 55-60

ISBN: 978-989-758-011-6

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

performance of this setup regarding spatial accuracy

of the eye tracker as well as timing jitter between the

stimulation presentation and EEG as well as eye

movement recordings.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

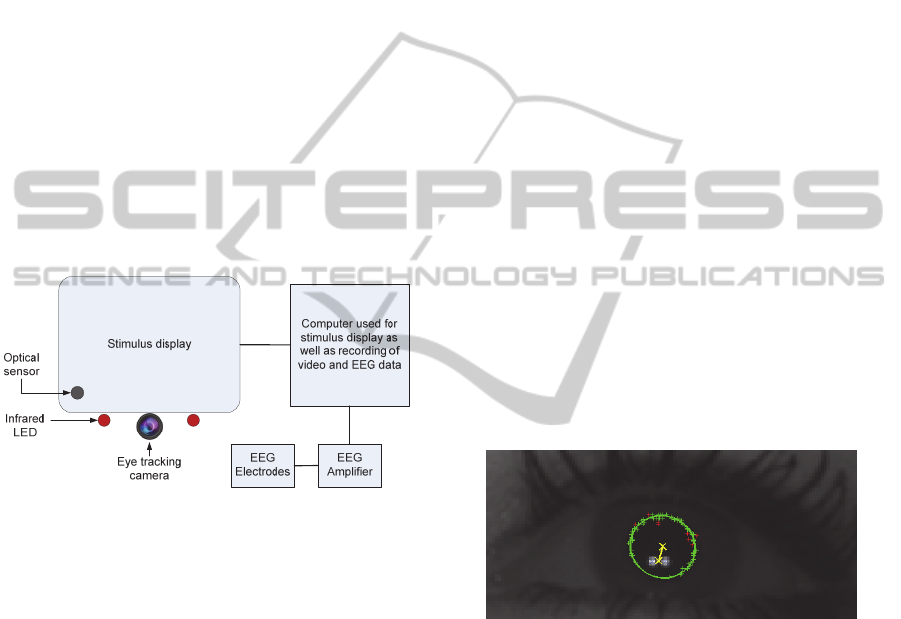

The developed system is outlined in

Figure

1, and comprises the following subsystems:

Eye Tracker - consisting of two infrared (IR)

light emitting diodes (LED) directed towards the

face of the subject, as well as a camera with infrared

recording capabilities used to record the eye

movement of the subject.

EEG Recorder - including an EEG cap with

active electrodes and a 16 channel EEG amplifier

with additional trigger input.

Visual Stimulus Presentation - consisting of a

large computer display with a dedicated area for

embedding the synchronization signal.

Figure 1: Overview of the hardware used in the combined

EEG / Eye tracking system.

Synchronization System - consisting of an optical

sensor measuring the signal in the dedicated

synchronization area on the stimulus display and

regulating the intensity of the IR LEDs based on the

signal from the optical sensor. The optical sensor

output is connected to the EEG amplifier as well.

All of the subsystems are controlled by a central

computer.

2.1 Eye Tracking Hardware

Eye movements were recorded with a remote video

eye tracking system using the pupil-center corneal-

reflection (PCCR) technique (Villanueva et al.

2009). The PCCR technique requires two infrared

illumination sources to produce two distinct

reflections on each eyeball and to provide general

illumination of the subjects face.

The camera used to record the eyes was a Basler

ACA640-100gc GigE camera with a resolution of

658 x 492 pixels and a maximum frame rate of 100

Hz. The camera used a fixed focus lens with a focal

length of 16 mm, which resulted in a field of view of

10 x 15 cm at the operating distance of 60 cm.

Attached to the lens was a Schneider Kreuznach 093

IR pass filter which helped control the exposure of

the camera sensor, since the IR LEDs were the

dominating source of infrared illumination in the

setup.

Each of the illumination sources in our system

comprised a cluster of four OSRAM SFH485

infrared (IR) light emitting diodes (LED). Since the

subjects were exposed to the infrared radiation for

extended periods of time, the current through each

LED was limited to avoid exceeding the long term

exposure limit for the retina (Jäger 2010). The

infrared LEDs were also used as part of the

synchronization system by modulating the global

illumination of the camera scene based on the signal

from the optical sensor. This is described further in a

later section.

2.2 Eye Tracking Algorithm

The PCCR technique uses the two reflections of the

LEDs on each cornea of the eyes as well as the

location of pupil center in the video stream to

determine the direction of the subjects gaze.

Figure 2: Eye tracking features extracted from each eye.

Blue: Corneal reflections. Yellow: PCCR vector. Green

and red: Edge points found by the starburst algorithm (Red

points were rejected by RANSAC step).

The reflections were extracted from each video

frame by calculating a difference of Gaussians

(DoG) and thresholding the result, which resulted in

a number of candidate clusters. The corneal

reflections for each eye were found as the best fit of

the distance and orientation of each pair of candidate

clusters to an experimentally established mean

distance and mean orientation, which was obtained

by manually measuring on a video frame from 12

test subjects.

The positions of the corneal reflections were

refined on a sub-pixel level by fitting a constrained

BIOSIGNALS2014-InternationalConferenceonBio-inspiredSystemsandSignalProcessing

56

2D Gaussian to the corneal reflection using least

squares.

The pupil centers were found using a modified

Starburst algorithm (Winfield & Parkhurst 2005).

The first step in the Starburst algorithm is to

threshold the vicinity of the corneal reflections to

find a rough estimate of the pupil’s location. This

first estimate is used as a starting point for a search

for gradients above an experimentally established

threshold along rays extending from the center of the

blob. If such gradients are found, the positions are

added to a list of potential edge points. This search is

repeated for each of the located potential edge

points, with rays directed back towards the center of

the blob. When the geometric center of the edge

points converges, the list of points is used in a

RANSAC (Fischler & Bolles 1981) based search for

an ellipse representing the edge of the pupil. The last

step in the algorithm is to refine the position of the

ellipse using an optimization step. The optimization

searches for the strongest gradient along the edge of

the pupil, with experimentally established

constraints on the size and eccentricity of the ellipse.

The output of the algorithm is the PCCR vector from

the center of the two corneal reflections to the center

of the pupil for each eye. The extracted features are

shown in Figure 2.

To map the relative locations of the corneal

reflections and pupil (PCCR vector) to a point on the

stimulus display, a mapping function was calculated

individually for each eye of each subject. The

mapping function from PCCR vector to the image

coordinates is a second order polynomial in two

variables of the form:

22

12 3 456

22

12 3 456

screen

screen

x

ax ay axyaxaya

ybxbybxybxbyb

, where

s

creen

x

and

s

creen

y

are the coordinates in the

image,

x

and

y

are the coordinates of the PCCR

vector, and

1...6

a

and

1...6

b

are subject specific

constants.

To determine the constants in the mapping

function, each subject was presented with a standard

calibration screen on the stimulus display with nine

fixation targets in a three-by-three grid. The subjects

were asked to fixate on each of the nine patterns in

turn, while 100 frames (1 second) of video were

recorded for each position. Since the position on the

stimulus display of each pattern was known, the best

fitting mapping constants could be found by

calculating the least squares fit on all PCCR vectors

extracted from the 900 frames of video.

2.3 EEG Recording Hardware

EEG data were recorded using a 16 channel G.tec

g.USBamp with the g.GAMMAsys active electrode

system. The data were recorded at a sampling rate of

1200 Hz and post processed with a band-pass filter

between 0.1 Hz and 200Hz. During recording all

electrodes were referenced to the Cz electrode

position and the cheek was connected to ground.

2.4 Visual Stimulus Presentation

and Synchronization

The presentation of visual stimulus as well as the

embedded synchronization signal was shown on a

26” LG DT-3003X display with a resolution of 1280

x 768 pixels and a refresh rate of 60 Hz. The face of

the subjects were placed 60 cm from the monitor

slightly below the center.

A dedicated area of 20 x 20 pixels in the lower

left corner of the stimulus display was used for the

embedded synchronization signal. The

synchronization signal can be viewed as a one bit

wide serial data link between the stimulus display

and the ET and EEG recorder. A ‘0’ is coded by

turning the dedicated area black, while a ‘1’ is

represented by a white area.

The detection of the synchronization signal on

the stimulus display is achieved by the use of an

optical sensor. The detected signal is sent to the

EEG amplifier and is used by the synchronization

hardware to modulate the illumination used in the

eye tracker. The amount of light from the high and

low level of this modulation is chosen to allow

robust detection of the synchronization signal from

the video stream, without compromising the fidelity

of the video through under- or overexposure of the

camera sensor.

When this is accomplished, the histogram of the

video frames with low illumination can be

transformed to match the frames with high

illumination before the ET algorithm.

The synchronization signal was extracted from

the video stream by calculating the number of pixels

whose intensities changed in a positive direction and

subtracting the number of pixels whose intensities

changed in a negative direction between each pair of

frames. The resulting signal showed a strong

resemblance with the time derivative of the original

synchronization signal and had strong positive and

negative peaks when the global illumination of the

scene changed rapidly. A typical example of this

kind of signal is shown in Figure 3 along with the

SynchronizationofElectroencephalographyandEyeTrackingusingGlobalIlluminationChanges

57

original synchronization signal as well as the time

derivative.

Figure 3: Original (s) and extracted (ET sync) sync signal.

The extracted signal is calculated as the normalized

difference between the number of pixel intensities

changed in a positive and negative direction.

3 RESULTS

3.1

Spatial Precision of the Eye Tracker

The spatial precision of the eye tracker was

evaluated by having a group of 12 subjects go

through the procedure of calibrating the eye tracking

system followed by a validation procedure.

Table 1: Bias and standard deviation of eye position for

the 9 areas of the display measured in degrees of visual

angle.

x: -0.18 ± 0.43 °

y: 0.05 ± 0.31 °

x: 0.13 ± 0.38 °

y: 0.30 ± 0.38 °

x: 0.01 ± 0.33 °

y: -0.20 ± 0.35 °

x: 0.22 ± 0.35 °

y: -0.17 ± 0.32 °

x: 0.18 ± 0.46 °

y: -0.33 ± 0.60 °

x: -0.40 ± 0.47 °

y: 0.54 ± 0.63 °

x: 0.01± 0.41 °

y: 0.18 ± 0.31 °

x: -0.31 ± 0.34 °

y: -0.13 ± 0.31 °

x: 0.34 ± 0.41 °

y: -0.25 ± 0.44 °

During the validation procedure a grid of 9 fixation

patterns was shown, one after the other, and one

second of eye movement was recorded while the

subject fixated on each pattern in turn. The accuracy

and precision of each of the 9 positions are shown in

visual angle in Table 1.

3.2

Measurement of Synchronization

Jitter

The synchronization of the stimulus display and the

eye tracker was subject to timing jitter. The primary

cause of this jitter is illustrated in Figure 4 where it

can be seen that with the eye tracker’s frame rate of

100 Hz, there can be a delay of up to 10 ms before a

change in the synchronization signal presented on

the stimulus display is recorded by the eye tracker.

To measure if any other sources of timing jitter

between the stimulus display and the eye tracker

were present, a simple stimulus, which is used in

visual evoked potentials (VEP) experiments, was

shown to one subject. The stimulus showed a

checkerboard with each square alternating between

black and white. One of the alternating squares

resided in the dedicated synchronization area on the

display.

The frequency of the alternating black and white

squares must divide the display refresh rate into an

integer, so a frequency of 7.5 Hz was chosen,

resulting in 4 consecutive frames of the same color

being displayed before changing color. The

synchronization signal was extracted from the video

stream (as shown in Figure 3) and the variation in

time between each period was calculated. The period

of the original signal was 133.3 ms, and the

maximum as well as minimum period extracted from

the eye tracking signal was 130.0 ms (13 frames)

and 140.0 ms (14 frames) respectively. In other

words, only a single frame of jitter was present in

the extracted synchronization signal. The signal-to-

noise ratio of the extracted synchronization signal

was 37.6 dB.

The amount of jitter in the EEG recordings was

evaluated with the same experimental setup as

described above, and the maximum as well as

minimum period extracted from the EEG data was

132.5 ms (159 samples) and 134.1 ms (161 samples)

respectively.

3.3

Real-time Performance

To determine if it would be possible to make the

stimulus display dependant on the current fixation

target in a closed loop experiment, the runtime

performance of the eye tracking algorithm was

evaluated. The processing frame rate on a 3.4 GHz

Intel Core i5 computer was 10 Hz.

4 DISCUSSION

The focus of the combined eye tracking and EEG

recording setup presented in this article is on high

flexibility and acceptable performance for HVS

experiments. Compared to state of the art

commercial remote eye tracking and EEG solutions,

such as the RED500 with EEG headset from

SensoMotoric Instruments GmbH (SMI) and

Emotiv, or the Smart Eye Pro from Electrical

Geodesics Inc. (EGI) and Smart Eye AB, the

presented system has some limitations due to the

choice of hardware used in the implementation.

BIOSIGNALS2014-InternationalConferenceonBio-inspiredSystemsandSignalProcessing

58

The methods developed are not limited to be

used with the chosen hardware, therefore, it is

expected that the performance of the system will

improve if the hardware is improved.

The camera used in the system was able to

achieve a temporal resolution of 10 ms with no more

than one frame of jitter, which makes it possible to

distinguish between saccades and fixations in the

eye movement data. If the dynamic behavior of the

saccades needs to be analyzed, a camera with a

higher temporal resolution must be used, such as the

500 Hz camera used in the RED500 eye tracker.

In general the jitter will be uniformly distributed

with a minimum and maximum of -10 and +10 ms

respectively. This amount of jitter makes it difficult

to use the eye tracking data directly for eliminating

EOG artifacts in the EEG data; however it gives a

rough estimate of the time of such artifacts, which

can then be refined further.

The amount of jitter in the EEG recordings was

measured to be within a single sample, and can

therefore be expected to be uniformly distributed

with a minimum and maximum of -0.8 and +0.8 ms

respectively. Since the peaks from the event-related

potentials (ERP) recorded by the EEG device are

generally separated by tens or hundreds of ms (Luck

2005), this amount of jitter does not affect the ability

to resolve individual ERPs.

The spatial accuracy of the system was measured

to be 1.26° in the worst case, which is comparable to

the performance of 1.01° achieved by (Villanueva et

al. 2009) and slightly worse than the advertized

accuracy of 0.4° for the RED500.

The obtained spatial resolution is sufficient to

use the system in a brain computer interface (BCI),

if the distance between fixation targets is kept above

this lower limit. For reliable control of a general

purpose computer interface designed for use by a

computer mouse, a higher spatial resolution is

required.

The human eye is able to attend to any target

within a 2 degree cone of the fixation point without

eye movement (Fairchild 1998). Even with higher

accuracy, there will still be a high degree of

ambiguity as to which target the subject is directing

the attention towards within this 2 degree cone, so

for many HVS studies, the obtained resolution is

sufficient.

The runtime performance of the software

algorithms suggests the possibility of using the

developed system in closed-loop experiments, where

the visual stimuli depend on the fixation point, if the

lower temporal resolution of 10 Hz is sufficient. A

complete evaluation of the possibility of real-time

performance with an optimized implementation of

Figure 4: Diagram showing the primary cause of timing

jitter between the stimulus display and the eye tracker and

EEG recording respectively.

the algorithms resulting in higher frame rates is

beyond the scope of this article.

In the experiments presented in the previous

section, the synchronization signal was used as a

very simple clock signal, however since arbitrary

data can be encoded in the synchronization signal, it

is possible to use this communication channel to

embed information about the stimuli directly in the

ET video. One suggested use of this feature would

be in the visual oddball paradigm (Courchesne et al.

1975), where different types of objects or characters

(target, non-target and novelty) are presented to the

subject sequentially. Using the synchronization

signal as a data channel, the type of object currently

presented to the subject could be embedded directly

in the eye tracking data.

The results presented in this paper will be used

as the foundation for future work in augmented

memory applications.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we have described the general

implementation of a combined EEG and eye

tracking system, as well as a new flexible way to

solve the problem of synchronizing the different data

sources in the system. The proposed synchronizing

method forgoes the need for low level control of the

sampling time of eye tracker and EEG as well as

presentation time of the visual stimuli. This in turn

eases the development of different types of stimuli

and enables the use of a wider range of eye tracking

camera and EEG recording equipment. The results

obtained with the reference implementation of this

SynchronizationofElectroencephalographyandEyeTrackingusingGlobalIlluminationChanges

59

method are comparable to similar systems with

respect to the spatial and temporal resolution, and

the amount of jitter in the system is primarily

dependent on the temporal resolution of the eye

tracking and EEG recording equipment.

REFERENCES

Agustin, J. S., 2009. Low-Cost Gaze Interaction : Ready to

Deliver the Promises. , pp.4453–4458.

Bell, G. & Gemmell, J., 2007. A Digital Life. Scientific

American, 296(3), pp.58–65.

Courchesne, E., Hillyard, S.A. & Galambos, R., 1975.

Stimulus novelty, task relevance and the visual evoked

potential in man. Electroencephalography and

Clinical Neurophysiology, 39(2), pp.131–143.

Davies, S., 2011. Still building the memex.

Communications of the ACM, 54(2), p.80.

Fairchild, M., 1998. Color Appearance Models, Reading,

Mass.: Addison, Wesley, & Longman.

Fischler, M. A. & Bolles, R.C., 1981. Random Sample

Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with

Applications to Image Analysis and Automated

Cartography. Communications of the ACM, 24(6).

Görgen, K. & Walter, S., 2010. Combining Eyetracking

and EEG. Publications of the Institute of Cognitive

Science, 15.

Jäger, C., 2010. Eye Safety of IREDs used in Lamp

Applications Application Note,

Luck, S., 2005. An Introduction to the Event-Related

Potential Technique (Cognitive Neuroscience) 1st ed.,

A Bradford Book.

Plöchl, M., Ossandón, J. P. & König, P., 2012. Combining

EEG and eye tracking: identification, characterization,

and correction of eye movement artifacts in

electroencephalographic data. Frontiers in human

neuroscience, 6(October), p.278.

Pohlmeyer, E. a et al., 2011. Closing the loop in cortically-

coupled computer vision: a brain-computer interface

for searching image databases. Journal of neural

engineering, 8(3), p.036025.

Sereno, S., 2003. Measuring word recognition in reading:

eye movements and event-related potentials. Trends in

Cognitive Sciences, 7(11), pp.489–493.

Villanueva, A. et al., 2009. A geometric approach to

remote eye tracking. Universal Access in the

Information Society, 8(4), pp.241–257.

Wang, J. et al., 2009. Brain state decoding for rapid image

retrieval. Proceedings of the seventeen ACM

international conference on Multimedia - MM ’09,

p.945.

Wang, Y. et al., 2008. Brain-computer interfaces based on

visual evoked potentials. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag,

27(5), pp.64–71.

Winfield, D. & Parkhurst, D.J., 2005. Starburst: A hybrid

algorithm for video-based eye tracking combining

feature-based and model-based approaches. In 2005

IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer

Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05) -

Workshops. IEEE, pp. 79–79.

BIOSIGNALS2014-InternationalConferenceonBio-inspiredSystemsandSignalProcessing

60