An Approach to Measure Knowledge Transfer in Open-Innovation

António Abreu

1,2

and Paula Urze

3,4

1

ISEL/IPL, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

2

CTS – Uninova, Almada, Portugal

3

FCT/UNL, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

4

CIHCT - Centro Interuniversitário de História das Ciências e da Tecnologia, Pólo Universidade Nova de Lisboa,

Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Knowledge Transfer, Open-Innovation, Collaborative Networks, Social Network Analysis.

Abstract: Recent studies show that a growing number of innovations that are introduced in the market come from

networks of enterprises that are created based on core competencies of each enterprise. In this context, the

characterization and assessment of the knowledge transfer among members within a network is an important

element for the wide adoption of the networked organizations paradigm. However, models for

understanding the knowledge transfer and indicators related to knowledge transfer in a collaborative

environment are lacking. Starting with some discussion on mechanisms of production and circulation of

knowledge that might operate in a collaborative environment, this paper introduces an approach for

assessing knowledge circulation in a co-innovation network. Finally, based on experimental results from a

Portuguese collaborative network, BRISA network, a discussion on the benefits, challenges and difficulties

found are presented and discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

In order to be competitive, enterprises must develop

capabilities that will enable them to respond quickly

to market needs. According to several authors, one

of the most relevant sources of competitive

advantage is the innovation capacity (Tidd, 2005);

(Argote, 2000). However, innovation capacity

requires access to new knowledge that enterprises do

not usually hold. As a result, enterprises can

improve their knowledge either from their own

assets, making sometimes high investments, or from

the knowledge that may be mobilized through other

enterprises based on a collaborative process. In fact,

there is an intuitive assumption that, when an

enterprise is a member of a long-term networked

structure, the existence of a collaborative

environment enables the increase of knowledge

production as well as the transfer of knowledge, and

thus the enterprises may operate more effectively in

pursuit of their goals (Abreu, 2010).

However, in spite of this assumption, it has been

difficult to prove its relevance due to the lack of

models that support mechanisms that explain the

production and transfer of knowledge in

collaborative environment. Furthermore, the absence

of indicators related to knowledge transfer – clearly

showing the amount of knowledge transferred and

the impact of this knowledge at a member level, for

instance, in terms of capacity for generating new

ideas, processes and products, organizational

improvement through the combination of the

existent resources, and diversity of cultures and

experiences of other enterprises – might be an

additional obstacle for a wider acceptance of this

paradigm.

In this context, the definition and application of a

set of indicators can be a useful instrument to the

network manager, and also to network members.

This work aims at contributing to answer the

following main questions:

• How is knowledge transferred from one network

member to another?

• How can competences circulation be analyzed in

a collaborative context based on an inter-

organizational perspective in order to support

decision-making processes?

2 SOME BACKGROUND

Upon reviewing the international literature, we find

183

Abreu A. and Urze P..

An Approach to Measure Knowledge Transfer in Open-Innovation.

DOI: 10.5220/0004811801830189

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES-2014), pages 183-189

ISBN: 978-989-758-017-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

many studies highlighting the societal importance of

innovation and knowledge within modern economies

(Castells, 2005); (Soete, 2006). "Knowledge

Economy" are highly regarded concepts, but we

could mention other interesting works from Toffler

(2003), Bell (1974), or Giddens (1990).

Knowledge always played an important role in

the economy. But only over the last few years has its

relative importance been recognised, just as that

importance is growing. However, the stock of

knowledge upon which economic activity is based

today is definitely much larger than in previous eras.

In the emergent economy and society, the

accumulation of knowledge becomes the main

motivational strength towards growth and

development (Gosman, 1991); (Maskel, 1999) and

(Urze, 2011).

Actually, the last decades have shown a

generalised concern about the study on how

companies create knowledge and, particularly, on

how they operate this transference. Knowledge is

recognised as a principal source of economic rent,

and the effective management of organizational

knowledge has increasingly been linked to

competitive advantage and is considered critical to

the success of the business firm. One of the

distinctive features of the knowledge-based

economy is the recognition that the diffusion of

knowledge is just as significant as its production,

leading to increased attention to "knowledge

distribution networks" and “national systems of

innovation”. These are the agents and structures

which support the advance and use of knowledge in

the economy and the linkages between them.

In this line of thought, Gibbons (1994) introduce

a distinction between Mode 1 knowledge

production, which has always existed, and Mode 2

knowledge production, a new mode that is emerging

alongside it and which is becoming more and more

relevant. While knowledge production used to be

located primarily at scientific institutions

(universities, government institutes and industrial

research labs) and structured by scientific

disciplines, its new locations, practices and

principles are becoming much more heterogeneous.

Mode 2 knowledge is produced in different

organizations, resulting in a heterogeneous practice.

The potential sites for knowledge production include

not only the traditional universities, institutes and

industrial labs, but also research centres, government

agencies, think-tanks, and high-tech spin-offs.

Mode 2 refers to a production of knowledge

which is not exclusively reserved for qualified

academic research but focuses on the different actors

integrated in a contextualised problem-solving

oriented process. The importance of knowledge is

then assessed by its social value and interest to

stakeholders engaged in the process of production.

Five main features of Mode 2 summarise how it

differs from Mode 1. First, Mode 2 knowledge is

generated in a context of application; Mode 1

knowledge can also result in practical applications,

but these are always separated from the actual

knowledge production in space and time. A second

characteristic of Mode 2 is transdisciplinarity, which

refers to the mobilisation of a range of theoretical

perspectives and practical methodologies to solve

problems. Transdisciplinarity goes further than

interdisciplinarity in the sense that the interaction of

scientific disciplines is much more dynamic.

Theoretical consensus cannot easily be reduced to

specific scientific parts. Thirdly, Mode 2 knowledge

is produced in a diverse variety of organisations,

resulting in a very heterogeneous practice. The

potential sites for knowledge generation include not

only the traditional universities, institutes and

industrial labs, but also research centres, government

agencies, think-tanks, high-tech spin-off companies

and consultancies. These sites are linked through

networks of communication, and research is

conducted in dynamic interaction. The fourth feature

is reflexivity. It means that researchers become more

aware of the societal consequences of their work

(‘social accountability’). Sensitivity to the impact of

the research is built in from the start. Novel forms of

quality control constitute the fifth characteristic of

the new production of knowledge. Traditional

discipline-based peer review systems are replaced by

additional criteria of economic, political, social or

cultural nature.

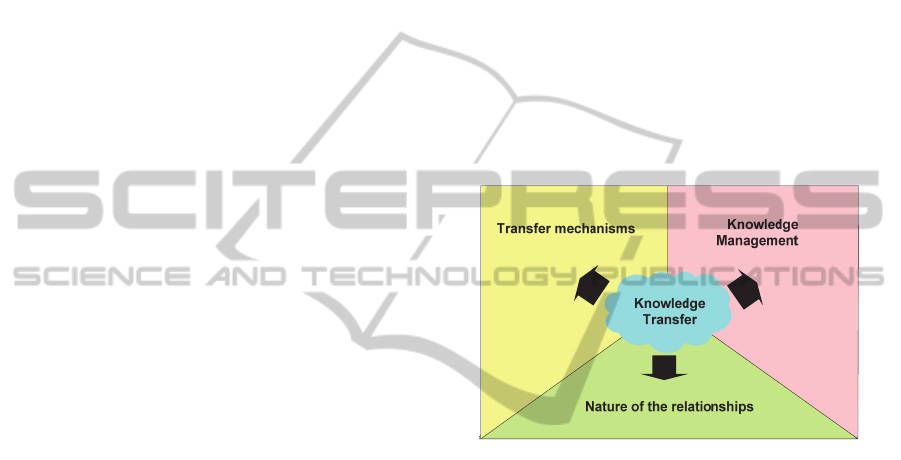

Figure 1: Production of knowledge environment 1A)

Mode I and 2B) Mode I.

In Mode 2, research is carried out in the context

of application in which there is a continuing

dialogue between interested parties – including

producers and users of knowledge – from the

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

184

beginning. Thus, the concept of knowledge transfer

has to be reconsidered. It cannot be understood as a

simple transmission of knowledge from the

university to the receiver. The participants may

include business people, venture capital, industry,

research centres and many others in addition to the

university. In short, all need to become actively

engaged in the process of knowledge production and

its transfer.

Figure 1 illustrates the two modes (I, II) of

knowledge production and its transfer taking as

environment the collaborative networks.

3 A MODEL TO ANALYSE

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Based on the literature (Gibbons, 1994); (Forzi,

2004); (Abreu, 2008); (Camarinha-Matos, 2008);

(Urze, 2012), and taking into account the context of

collaborative networks, to analyse and understand

the processes and mechanisms of knowledge transfer

in a collaborative network, it is necessary to develop

a model that supports, as a first approach, the

following perspectives:

• Transfer Mechanisms – This perspective

focuses on the identification and characterisation

of distinct ways of “physical” interrelationship

that support the process of knowledge transfer

between enterprises within a network, such as

internal publications, external publications,

reports, patents, exchange of resources between

organizations, videoconferencing, infrastructure

to support collaborative processes (e.g.

workgroup tool), telephone / mobile phone,

informal meetings, and periodic meetings.

• Competences Management - This perspective

addresses the principles, policies, and

governance rules that may facilitate or constrain

the processes of creating the competence and

searching for competences by the members of

the network. Therefore, general issues such as

definition of accessibility levels (e.g. public,

internal to network members or private),

definition of policies in terms of competence

dissemination among members of the network,

definition of principles to assure the transparency

and traceability of the competences in the

network), and definition of rules in terms of

Intellectual Property rights (IPR) (e.g.

confidential or non-confidential) are considered

here.

• Nature of the Relationships - The nature of the

relationships determines the way collaborative

space enables or facilitates the flow of

knowledge among enterprises. Thus, this

perspective focuses on the identification and

characterisation of the various types of

relationships that enterprises may have with

other enterprises within the network: the

relationships with new enterprises created from

existing enterprises that belong to the network

(e.g. spin-offs and start-ups) and also the

relationships between the network as a whole

and external entities (e.g. suppliers, customers,

end-users, competitors, external institutions, and

potential new partners).

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed model for the

analysis of knowledge transfer in the context of

network organizations.

Figure 2: Knowledge transfer model.

In order to analyse the processes of knowledge

transfer in a collaborative network, it is necessary to

develop a model that supports the analysis of

knowledge transfer among enterprises.

In an attempt to contribute to such need, we start

with the assumption that the processes of knowledge

transfer in a collaborative network can be

represented graphically through a graph.

Therefore, as a first approach, using concepts

from Social Network Analysis it is possible to apply

several graph properties and relating them to

circulation of knowledge.

To illustrate the potential application of graph

properties let us consider some simple examples

“archetypes” in this discussion. Assuming the degree

of a node is a measure of the “involvement” of the

enterprise in the network, it may be relevant to

analyze the knowledge transfer process based on this

perspective. According this approach, a network can

be classified as decentralized or centralized. A

network is decentralized when all enterprises have

equal value of nodal degree (in-degree and out-

degree), otherwise the network is centralized.

AnApproachtoMeasureKnowledgeTransferinOpen-Innovation

185

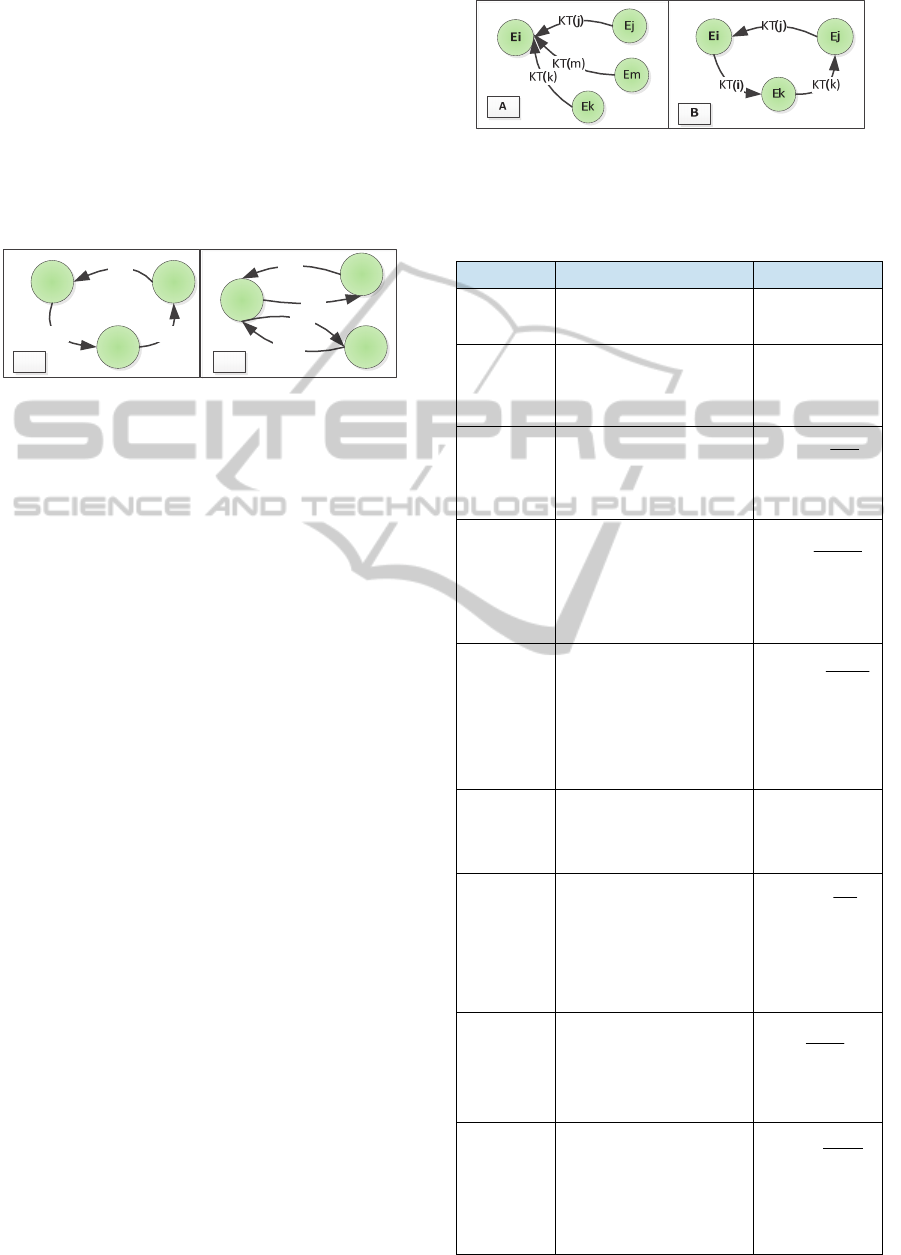

Figure 3A illustrates an example of decentralized

knowledge transfer network supported by a

mechanism of indirect reciprocity and Figure 3B)

shows an example of centralized knowledge transfer

network supported by a mechanism of direct

reciprocity. However, comparing these two types of

network, a knowledge transfer process supported on

a decentralized network might be more attractive,

since the number of provide/receive new

competences is identical for all enterprises.

Figure 3: Decentralized vs. centralized knowledge transfer

network.

Based on analyse of network connectivity Figure

4A) shows an example of acyclic network. This type

of network is characterized by a weak connectivity

among enterprises.

According to this approach the existence of

acyclic knowledge transfer network means that there

are enterprises that provide/receive competences

to/from someone and do not receive/provide none

from/to others. As a result, for some enterprises (in

this case, enterprise E

i

and E

m

) the participation in a

collaborative process supported by acyclic

knowledge transfer network might not be

advantageous, unless one of the following

assumptions is verified:

The enterprises believe that its actions can be

perceived as an investment and later on, they can

get some competences or benefits from others.

The enterprises that receive new competences

recognize a “debit” as a result of contributions

received in the past.

On the other hand, Figure 4B) shows an example of

cyclic network. A cycle is a closed walk of at least

three nodes in which all links are distinct, and all

enterprises except the beginning and ending

enterprises are distinct. Consequently, the

development of a knowledge circulation process

based on a cyclic transfer network assumes that

enterprises provide/receive new competences

to/from someone and simultaneously

receive/provide new competences from/to others. As

a result, the participation in a knowledge transfer

process supported by cyclic or closed walk

knowledge transfer network is usually more

attractive.

Figure 4: Acyclic vs. Cyclic network of knowledge

transfer.

Table 1: Indicators for competences production and

circulation analysis.

Indicator Potential Use Expression

Total of

Competences

(C)

This indicator measures the level of

versatility/polyvalence of the

network.

C – Number of

distinct competences

involved in the

network

Total of

enterprise

Owned

Competences

(TOC)

This indicator measures the level of

expertise and the potential capacity

of an enterprise in terms of

knowledge transfer.

TOC = Number of

competences held by

an enterprise.

Apparent

Owned

Competence

Index (AOCI)

An enterprise with an AOCI close to

one means that this enterprise is the

owner of nearly all competences

available within the network.

M

TOC

AOCI

M – Number of

competences held by

the network

Owned

Competences

Index

(OCI

i

)

Normalization of the number of

competences held by an enterprise

in relation to other members of the

network.

Benchmarking with enterprises

involved in other networks.

N

j

j

i

i

TOC

TOC

OCI

1

N – Number of

enterprises involved

in the network

Owned

Competences

Progress Ratio

(OCPR

i

)

The aim of this ratio is to measure

the progress of competences held by

an enterprise over a period of time.

If:

decreasedOCPR

increasedOCPR

changenoisthere

OCPR

i

i

tt

i

1

1

1

21

,

Benchmarking with enterprises

involved in other networks

1

2

21

,

t

i

t

i

tt

i

OCI

OCI

OCPR

12

tt

Competences

Abundance

(CA

i

)

This indicator measures the level of

abundance of a competence inside

the network. A competence with a

CA near to zero means that it is

exclusive because it is owned by

few enterprises of the network.

CA

i

= Number of

ownership relations

connected to

competence i.

Apparent

Competences

Exclusivity

Index

(ACEI

i

)

This index gives a simple to

compute measure of exclusivity of a

competence. A competence with an

ACEI near to zero means that such

competence belongs to few

enterprises. On the other hand, a

competence with an ACEI close to

one means that such competence is

owned by all enterprises in the

network.

N

CA

ACEI

i

i

N –Number of

enterprises involved

in the network

Competences

Exclusivity

Index

(CEI

i

)

Normalization of the level of

exclusivity of a competence in the

network.

Benchmarking with other networks.

M

j

j

i

i

CA

CA

CEI

1

M – Number of assets

held by the network

Competences

Exclusivity

Progress Ratio

(CEPR

i

)

The aim of this ratio is to measure

the variation of exclusivity of a

competence over a period of time.

If:

decreasedCEPR

increasedCEPR

changenoisthere

CEPR

i

i

tt

i

1

1

1

21

,

Benchmarking with other networks

1

2

21

,

t

i

t

i

tt

i

CEI

CEI

CEPR

12

tt

B

Ei

Ej

KT(j)

KT(m)

Em

KT(i)

KT(i)

Ei Ej

KT(j)

KT(i)

Ek

KT(k)

A

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

186

Since, the most favourable network for

promotion of knowledge transfer is dependent on the

existence of cycles or close walk processes, it is

useful to analyse in detail the conditions that drive

the emergence of this type of structure. Therefore, in

order to establish a close walk process it is necessary

to satisfy the following three conditions:

Provide Condition – Enterprises must provide

new competences. For each enterprise E

j

, there is

at least another enterprise E

k

to which E

j

provides a new competence.

Receive Condition – Enterprises have to receive

new competences. For each enterprise E

k

there is

at least another enterprise E

j

from which E

k

receives a new competence.

Identity Condition – Enterprise E

k

≠ E

j

.

Taking into account the context of collaborative

networks, and combining concepts borrowed from

the Social Networks Analysis (SNA) area. Table 1

shows a number of basic indicators that can

contribute to evaluate the level of expertise of an

enterprise and how production and circulation of

knowledge is done within the network. Furthermore,

these indicators can be determined for a particular

collaboration process or over a period of time

(average values) and can be used in decision-making

processes, such as the planning of a new

collaborative network.

However, the use of graphs implies a partial

view and consequently, a limitation of this approach.

In order to have a full description it is important to

combine other tools (such as: game theory, causal

models, fuzzy tools, belief networks, etc.) to analyse

in detail the impact of the three dimension proposed

in a knowledge transfer process.

4 BRISA CASE STUDY

The paper’s empirical section is based on one case

study pointed to the largest Portuguese motorway

operator. Brisa - Auto-estradas de Portugal, founded

in 1972, currently operates, on a concession basis, a

network of 11 motorways, with a total length of

around 1096 km, constituting the main Portuguese

road links. The Brisa co-innovation network is a

long-term collaborative network that has more than

30 members from several domains and business

activities (e.g. researches institutions, universities,

associations, governmental entities, start-ups,

business angels, and suppliers).

The empirical work is grounded on two main

projects developed by BRISA, namely E_TOLL –

Electronic Tolling System a self-service toll lane

where it is possible to pay by a bank card, money

and ALPR – Advanced License Plat Recognition an

enforcement system based on the automatic license

plate recognition for situation where the vehicle is

not equipped with an on-board-unit (OBU) or the

OBU fails to electronically identify the vehicle. In

the case study three techniques were combined to

carry out the empirical research: in-locu observation

of the work processes, semi-directive interviews and

questionnaires addressed to actors belonging to

different organizations that take part of E_TOLL and

ALPR.

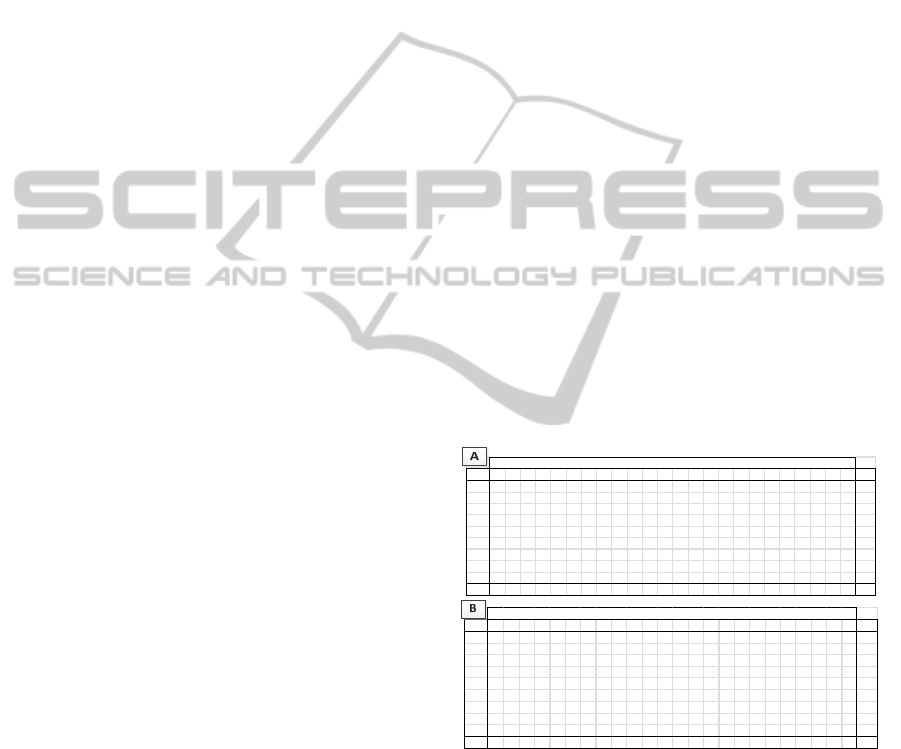

Taking into account the data collected, Table 2A

shows the types of competences used by each

partner in the collaborative projects, and Table 2B

identifies the types of competences held by each

partner in the end of the collaborative projects.

Applying the equations defined in Table 1, Table

3A evaluates the production of new knowledge

based on the number of distinct competences held by

network in the end of the project E_TOLL and

ALPR, and the number of different competences

used by the network when the projects started. Based

on these data, it is possible to verify that 6 new

competences were produced (C19, C20, C21, C22,

C23, and C24).

Table 2: Record of the competences.

Entity C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 C11 C12 C13 C14 C15 C16 C17 C18 C19 C20 C21 C22 C23 C24 Total

O1 111100000000000000000000 4

E1 010100000000000000000000 2

E2 000000000000000001000000 1

E3 000010000000000000000000 1

E4 010101000000000000000000 3

E5 000000100000000000000000 1

E6 000000000001111100000000 5

E7 100000000000001010000000 3

O2 000000011110000000000000 4

Total 231311111111112111000000 18

Competences

Entity C1 C2 C3 C4 C5 C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 C11 C12 C13 C14 C15 C16 C17 C18 C19 C20 C21 C22 C23 C24 Total

O1 111100000000000000111110 9

E1 010100000000000000000000 2

E2 001100000000000001000000 3

E3 000010000000000000000000 1

E4 111101000000000000000000 5

E5 000000100000000000000000 1

E6 000000000001111100000000 5

E7 100000000000001010000000 3

O2 000000011110000000000001 5

Total 333411111111112111111111 34

Competences

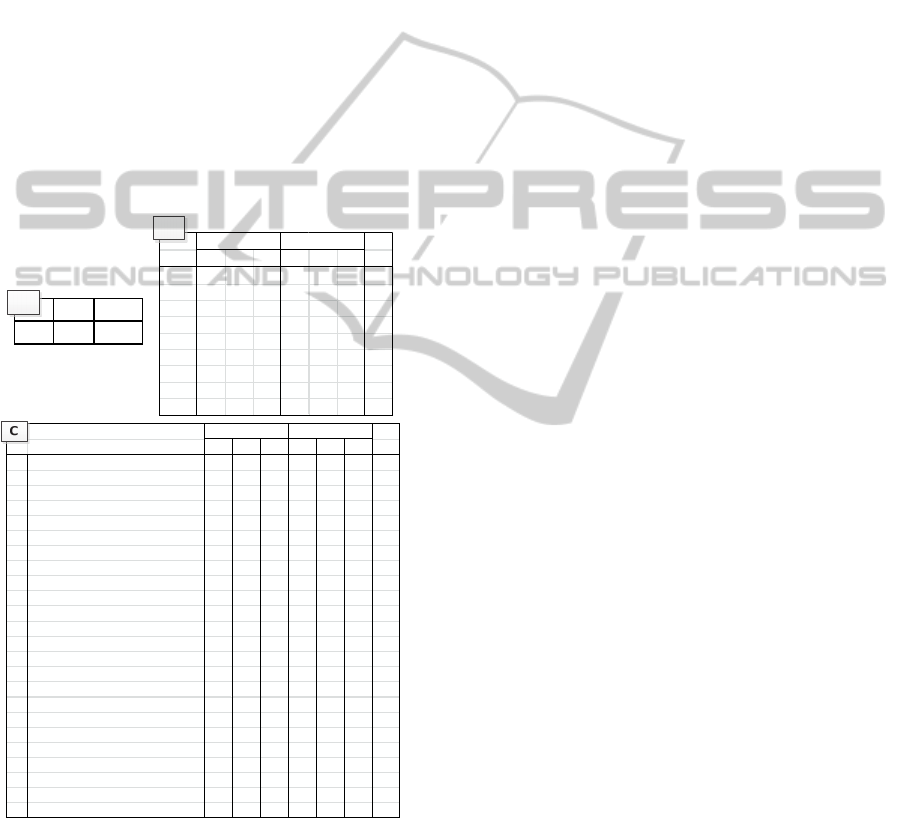

Table 3B shows indicators to analyse, for

instance, how the competences are held by network

members, and the benefits of the entities’

participation in a collaborative process. Assuming

that the benefits of an entity can be viewed as the

capacity of involvement in a collaborative process;

in this case, we are not particularly concerned with

whether this benefit is due to the development of

exclusive competences, but rather in analysing how

many distinct competences might be performed by a

member. According to Owned Competences

AnApproachtoMeasureKnowledgeTransferinOpen-Innovation

187

Progress Ratio (OCPRI), at the end of those two

projects, there are three members, O1, E2, and E4

that had a significant increase in terms of acquiring

new competences that might be used in the future,

and consequently, they have more opportunities to

participate in collaborative processes than those who

have a low ratio.

Table 3C illustrates some examples of indicators

to evaluate, for instance, the level of exclusivity of

each competence and the circulation of competences

among members. Based on these data, it is possible

to verify, for example, that according to

Competences Exclusivity Progress Ratio (CEPR),

the highest value belongs to competence C3

(infrared illumination) that had a great proliferation

among members of the network.

Table 3: Indicators for Knowledge production and

circulation analysis.

Start Finish

C 18 24

A

Entity

TOC AOCI OCI TOC AOCI OCI OCPR

O1 4 0,22 0,17 9 0,38 0,27 1,64

E1 2 0,11 0,08 2 0,08 0,06 0,73

E2 1 0,06 0,04 3 0,13 0,09 2,18

E3 1 0,06 0,04 1 0,04 0,03 0,73

E4 3 0,17 0,13 5 0,21 0,15 1,21

E5 1 0,06 0,04 1 0,04 0,03 0,73

E6 5 0,28 0,21 5 0,21 0,15 0,73

E7 3 0,17 0,13 3 0,13 0,09 0,73

O2 4 0,22 0,17 5 0,21 0,15 0,91

Start Finish

B

Competences CA ACEI CEI CA ACEI CEI CEPR

C1 Computervision 2 0,22 0,11 3 0,33 0,09 0,79

C2 SoftwareEngi nee ring 3 0,33 0,17 3 0, 33 0,09 0,53

C3 Infraredillumination 1 0,11 0,06 3 0,33 0,09 1,59

C4 Automaticpatternrecogniti on 3 0,33 0,17 4 0, 44 0,12 0,71

C5 Tollsystems 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C6 InformationSystemsArchi te cture , 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C7 IndustrialDesign 1 0,11 0,06 1 0,11 0,03 0,53

C8 Modellingofproducts 1 0,11 0,06 1 0,11 0,03 0,53

C9 Rapidprototyping 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C10 Developmentofmolds 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C11 Plasticinje ction 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C12 FunctionalTe sts 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C13 SoftwareDeve lopment 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C14 SoftwareArchitecture 1 0,11 0,06 1 0,11 0,03 0,53

C15 ProjectManagement 2 0,22 0,11 2 0,22 0,06 0,53

C16 FunctionalAnalysis 1 0,11 0,06 1 0,11 0,03 0,53

C17 Remotemonitoring 1 0,11 0,06 1 0,11 0,03 0,53

C18 Supplierofequipmentforimagecapture 1 0,11 0,06 1 0, 11 0,03 0,53

C19 ElectronicTollCollection(ETC)systems 0 0,00 0,00 1 0, 11 0,03 ‐‐‐‐

C20 InformationSystemsopentomulti‐vendor 0 0,00 0,00 1 0,11 0,03 ‐‐‐‐

c21 Automati cvehicleidentificationsyste ms 0 0,00 0, 00 1 0,11 0,03 ‐‐‐

C22 Communicationsystemsbetweenvehicles 0 0,00 0,00 1 0,11 0,03 ‐‐‐

C23 Classificationsystemsofvehicles 0 0,00 0,00 1 0,11 0,03 ‐‐‐‐

C24 Shortrunproduction 0 0,00 0,00 1 0,11 0,03 ‐‐‐

FinishStart

5 CONCLUSIONS

Reaching a better characterization and understanding

of the mechanisms of production and circulation of

knowledge in collaborative networks is an important

element for a better understanding of the behavioral

aspects, and also to improve the sustainability of this

organizational form.

The development of a set of indicators to capture

and measure the circulation and production of

knowledge can be a useful instrument to the

manager of this network, as a way to support the

promotion of collaborative behaviors, and for a

member as a way to extract the advantages of

belonging to a network. Using simple calculations as

illustrated above, it is possible to extract some

indicators. Some preliminary steps in this direction

were presented. However, the development of

indicators to measure the potential impacts and

worth related to production and circulation of

knowledge, for instance, at a member level, in terms

of capacity of generating new ideas, development of

new processes, new products or services,

organizational improvement through the

combination of the existent resources and diversity

of cultures and experiences of other enterprises is

not yet well understood and requires further research

and development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by BRISA Innovation

and Technology (BIT) through a research and

development project.

REFERENCES

Abreu, A. and L. M. Camarinha-Matos, 2010.

Understanding Social Capital in Collaborative

Networks, in

Balanced Automation Systems for Future

Manufacturing Networks

, Á.O. Bas., R.D. Franco.,

and P.G. Gasquet, (Eds.), Boston, Springer. pp. 109 -

118.

Abreu, A., P. Macedo, et al., 2008. Towards a

methodology to measure the alignment of value

systems in collaborative networks.

Innovation in

Manufacturing Network

. A. Azevedo (Eds.) Boston,

Springer, pp. 37- 46.

Argote, L., et al., 2000. Knowledge Transfer in

Organizations: Learning from the Experience of

Others.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes,

82(1).

Bell, D., 1974.

The coming of postindustrial society,

Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Camarinha-Matos, L. M., P. Macedo, et al., 2008.

Analysis of core-values alignment in collaborative

networks.

Pervasive Collaborative Networks. L. M.

Camarinha-Matos and W. Picard (Eds.), Boston,

Springer, pp.53 - 64.

Castells, M., 2005. A era da informação: economia,

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

188

sociedade e cultura, Vol I. A sociedade em rede,

Lisboa

, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Forzi, T., M. Peters, and K. Winkelmann, 2004. A

Framework for the Analysis of Knowledge

Management within Distributed Value-creating

Networks, in Proceedings of I-KNOW'04. Graz,

Austria.

Gibbons et al., 1994. The New Production of Knowledge:

The Dynamics of Science and Research in

Contemporary Societies

, London, Sage.

Giddens, A., 1990.

The Consequences of Modernity.

Cambridge.

Gosman, G. and E. Helpman, 1991. Innovation and

Growth in the Global Economy,

Cambridge: MIT

Press

.

Maskel P. and Malmberg, A., 1999. Localized learning

and industrial competitiveness, Cambridge Journal of

Regions, Economy and Society

, Oxford University

Press.

Soete, L., 2006. A Knowledge Economy Paradigm and its

Consequences

, in A. Giddens, P. Diamond and R

Liddle (ed)

Global Europe, Social Europe,

Cambridge, Polity Press, pp.193-214.

Tidd, J., J. Bessant, and K. Pavitt 2005. Managing

Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and

Organizational Change,

Hong Kong: John Wiley &

Sons, Ltd.

Toffler, A., 2003. A terceira vaga, Lisboa, Edições livros

do Brasil

Urze, P., 2011. Networked R&D Units: Case Studies on

Knowledge Transfer Processes

, Adaption and Value

Creating.

Collaborative Networks, in Camarinha-

Matos,

Luis M.; Pereira-Klen, Alexandra

Afsarmanesh, Hamideh (Eds.) Boston, Springer.

Urze, P., Abreu, A., 2012. Knowledge Transfer

Assessment in a Co-innovation Network.

Collaborative Networks in the Internet of Services.

L.M. Camarinha-Matos, L. Xu, and H. Afsarmanesh

(Eds.), Boston, Springer, pp. 605–615.

AnApproachtoMeasureKnowledgeTransferinOpen-Innovation

189