A Method for Semi-automatic Explicitation of Agent’s Behavior

Application to the Study of an Immersive Driving Simulator

K

´

evin Darty

1

, Julien Saunier

2

and Nicolas Sabouret

3

1

Laboratory for Road Operations, Perception, Simulators and Simulations (LEPSIS),

French Institute of Science and Technology for Transport, Development and Networks (IFSTTAR),

14-20 Boulevard Newton Cit

´

e Descartes, 77447 Marne la Vall

´

ee, France

2

Computer Science, Information Processing and Systems Laboratory (LITIS), National Institute of Applied Sciences (INSA)

of Rouen, Avenue de l’Universit

´

e - BP8, 76801 Saint-

´

Etienne-du-Rouvray Cedex, France

3

Computer Sciences Laboratory for Mechanics and Engineering Sciences (LIMSI),

National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), Rue John von Neumann, BP133, 91403 Orsay Cedex, France

Keywords:

Multi-agent Simulation, Credibility Evaluation, Objective and Subjective Approach, Behavior Clustering and

Explicitation.

Abstract:

This paper presents a method for evaluating the credibility of agents’ behaviors in immersive multi-agent

simulations. It combines two approaches. The first one is based on a qualitative analysis of questionnaires

filled by the users and annotations filled by others participants to draw categories of users (related to their

behavior in the context of the simulation or in real life). The second one carries out a quantitative behavior

data collection during simulations in order to automatically extract behavior clusters. We then study the

similarities between user categories, participants’ annotations and behavior clusters. Afterward, relying on

user categories and annotations, we compare human behaviors to agent ones in order to evaluate the agents’

credibility and make their behaviors explicit. We illustrate our method with an immersive driving simulator

experiment.

1 INTRODUCTION

The validation of the credibility and realism of agents

in multi-agent simulations is a complex task that has

given rise to a lot of work in the domain of multi-

agent simulation (see e.g. (Caillou and Gil-Quijano,

2012)). When the number of agents increases, Dro-

goul shows (Drogoul et al., 1995) that the valida-

tion of such a simulation requires an evaluation of

the system at the macroscopic level. However, this

does not guarantee validity at the microscopic level,

i.e. the validity of the behavior of each agent in the

system. In some simulations such as virtual reality

environments, where humans coexist with simulated

agents, the human point of view is purely local and

behavior is considered at the microscopic level. In-

deed, if the agents’ behavior is inconsistent, user im-

mersion in the virtual environment (i.e. the human’s

feeling to belong to the virtual environment) is bro-

ken (Fontaine, 1992; McGreevy, 1992).

Methods and implementations of behaviors are

not directly observable by the user, only the result-

ing behaviors are. This is why, this notion of credi-

bility at the microscopic level does not depend on the

way the behaviors are modeled. The outside observer

judges them and this perception depends on many

factors including sensory elements (visual rendering,

haptic, proprioceptive, etc.) (Burkhardt et al., 2003;

Stoffregen et al., 2003). The term used in the liter-

ature to denote this feeling of realism is called pres-

ence effect (Witmer and Singer, 1998). The multiple

techniques that are used to enhance the presence ef-

fect (called immersion techniques) are mainly evalu-

ated on subjective data. Consequently, the evaluation

of the presence effect resulting from a virtual reality

(VR) device is done with methods from human sci-

ences.

In this paper, we propose to evaluate the agents’

credibility at the microscopic level. To do so, we

combine subjective evaluation methods from human

sciences with automated behavior traces analysis

based on artificial intelligence algorithms. Section 2

presents the state of the art. Section 3 explains the

general method we have developed, which relies on

data clustering and comparison, and section 4 gives

the details of the underlying algorithms. Section 5

81

Darty K., Saunier J. and Sabouret N..

A Method for Semi-automatic Explicitation of Agent’s Behavior - Application to the Study of an Immersive Driving Simulator.

DOI: 10.5220/0004821400810091

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2014), pages 81-91

ISBN: 978-989-758-016-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

presents its application on an immersive driving sim-

ulator and its results.

2 STATE OF THE ART

In this section, we first define the notion of behavior.

We then present existing subjective and objective ap-

proaches.

2.1 Levels of Behavior

Behaviors are a set of observable actions of a person

in the environment. There are different levels of hu-

man behavior (Pavlov and Anrep, 2003): The lowest

level corresponds to simple reflex actions such as go-

ing into first gear in a car. These behaviors are similar

to the agent’s elementary operations. The intermedi-

ary level is tactical, it is built on an ordered sequence

of elementary behaviors such as a car changing lane

on the highway. The highest level of behavior is the

strategic level, corresponding to the long term. It is

based on a choice of tactics and evolves according to

the dynamics of the environment and the mental state

of the person (Premack et al., 1978) as in overtaking

a truck platoon or choosing a stable cruise speed. In

our study, we evaluate the behavior of the agents at

the last two levels (tactical and strategic).

2.2 Subjective Approach

The subjective approach comes from the VR field and

aims at validating the agents’ behavior in simulation.

It consists in evaluating the general (or detailed) im-

mersion quality via the presence effect using ques-

tionnaires (Lessiter et al., 2001). In our case, the no-

tion of presence is too broad because it includes var-

ious elements (visual quality, sound quality, etc.) of

the device, but does not detail the virtual agents be-

havior credibility component.

However subparts of the presence effect evalua-

tion are consistent with our goal:

• The behavioral credibility: Users interacting with

the agent believe that they observe a human be-

ing with his own beliefs, desires and personal-

ity (Lester et al., 1997),

• The psychological fidelity: The simulated task

generates for the user an activity and psychologi-

cal processes which are similar to those generated

by the real task (Patrick, 1992). The simulator

produces a similar behavior to the one required in

the real situation (Leplat, 1997).

In this article, we focus on the behavioral credibil-

ity and especially on its qualitative and quantitative

evaluation. A solution is to set up a mixed system

where humans control avatars in the virtual environ-

ment. The evaluation of presence or of behavioral

credibility is subjective. This is why it is sensitive to

psychological phenomena such as the inability to ex-

plain one’s judgments (Javeau, 1978). Moreover this

evaluation does not necessarily explain missing be-

haviors nor the faults of the behaviors judged as not

credible.

That is why we propose to complete these subjec-

tive studies with an objective analysis of simulation

data.

2.3 Objective Approach

The objective approach is generally used in the field

of multi-agents systems: It consists in comparing

quantitative data produced by humans with data pro-

duced by different categories of virtual agents (Cail-

lou and Gil-Quijano, 2012). It aims at verifying that

the behavior of the agents is identical to the one ob-

served in reality and therefore at evaluating the real-

ism of the simulation. When the number of agents in-

creases, objective evaluation is generally done at the

macroscopic level because real data are both more

readily available and easier to compare with sim-

ulation outputs (Champion et al., 2002; Maes and

Kozierok, 1993).

This macroscopic validation is necessary for the

VR but not sufficient to validate the agents’ behavior.

A valid collective behavior does not imply that the in-

dividual behaviors that compose it are valid. Thus,

an analysis at the microscopic level is required, al-

though microscopic data analysis and comparison is

complex. Some tools are available to summarize in-

teractions of a multi-agent system for manual debug-

ging (Serrano et al., 2012). Nevertheless, as simula-

tion data involving participants consist of more than

just message exchange variables, these tools are not

directly applicable to complex and noisy data. A so-

lution for data analysis, adopted by (Gonc¸alves and

Rossetti, 2013) for driving tasks consists of classify-

ing participants according to variables. However, our

method deals with a larger amount of both variables

and participants, increasing the clustering task diffi-

culty. It also provides explicit high-level behaviors

via external annotation.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no tool to

analyze strategic behavior in simulation combining

both a validation of behavioral credibility and simi-

larities between humans and virtual agents. Subjec-

tive and objective approaches complement each other

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

82

in two different ways: human expertise and raw data.

3 OBJECTIVE AND APPROACH

Our goal is the evaluation of the agents of a multi-

agents simulation at a microscopic level, in the con-

text of virtual environments. The method we pro-

pose is based on the aggregation of individual data

(for both agents and human participants) into behav-

ior clusters that will support the actual behavior analy-

sis. In this view, behavior clusters act as abstractions

of individual traces. This paper details the compu-

tation of such clusters (section 4) and their use for

behavior analysis (section 5). The originality of our

model is that we use the two available types of data:

objective data with logs and subjective data via ques-

tionnaires.

3.1 General Approach

The general architecture of the method is described

in the Figure 1 and the data processing is detailed in

Figure 4. It consists of 4 main steps: collection of

data in simulation, annotation of this data, automatic

clustering of data, and clusters comparison.

The first step of our method is to collect data about

human participants. We consider both subjective data,

using questionnaires about their general habits and

their adopted behaviors in the given task, and objec-

tive data, using immersive (or participatory) simula-

tion in the virtual environment. The raw data from

participants’ experiments in the simulator is called

logs and the answers to questionnaires is called habits

in the figure.

The second step is to refine this data by 1) produc-

ing new simulations (or “replays”) in which the hu-

man participant has been replaced by a virtual agent;

and 2) having all replays (with human participants and

with virtual agents) being annotated by a different set

of participants, using the behavior questionnaire. This

step produces a set of annotations.

Our objective is twofold. First, we want to study

the correlation between participants’ categories and

their behaviors observed in the simulation so as to ver-

ify that the automated clustering of observation data

is related to task-related high-level behavior. Sec-

ond, we need to compare participants’ behavior and

agents’ behavior so as to report on the capability of

agents to simulate human behavior. In both cases,

this cannot be done on raw data (should it be ques-

tionnaires or data logs). Logs, especially in the case

of participants, are noisy: two different logs can rep-

resent the same type of tactic or strategic behavior.

This is the reason why, in order to generalize the anal-

ysis of our logs to a higher behavior level, we pro-

pose to use behavior categories (called abstractions

in the figure). These categories serve as abstraction

to the logs by gathering together, within the same

cluster, different logs representative of the same high

level behavior. This is done using automatic unsuper-

vised clustering methods (because supervised algo-

rithms require labeling by an expert of a large amount

of logs). In the same way, we use clustering methods

on the two questionnaires habits and annotations.

The comparison of these abstractions is our fi-

nal step. We both evaluate the similarity between

agents and humans logs and the annotated behaviors

(dashed arrow number 1); and between the logs and

self-reported habits for humans (dashed arrow num-

ber 2). While the first comparison allows us to evalu-

ate the level of credibility of our virtual agents in the

simulation, the second one is used to verify that the

logs automated clustering corresponds to task-related

high-level behaviors. If there is a strong similarity be-

tween the composition of behavior clusters and partic-

ipant self-reported categories (habits), it then means

that behavior clusters are meaningful in terms of par-

ticipant typology. Note that this comparison is mean-

ingful if and only if we use the same sort of indicators

for habits and annotations.

Human Participants and Agents

For the comparison between participants’ behavior

clusters and agents’ ones, we collect the same logs

for simulated agents as for the participants. As will

be discussed in section 4.2, the clustering algorithm

does not work directly on raw data: we use higher-

level representation based on expert knowledge on the

field.

Different types of agents are generated by explor-

ing the parameter space such as normativity, experi-

ence, decision parameters . . . The agents are placed in

an identical situation to that presented to participants,

so that the same logs are collected. The clustering

is done on both agents and human participants logs,

gathered together in the general term of main actors

(see section 4.2).

For the evaluation step, it is possible to distinguish

three cluster types:

1. The clusters containing both human and agent

main actors; they corresponds to high-level be-

haviors that are correctly reproduced by the

agents.

2. Those consisting of simulated agents only; they

correspond to behaviors that were produced only

by the agents. In most cases, it reflects simula-

AMethodforSemi-automaticExplicitationofAgent'sBehavior-ApplicationtotheStudyofanImmersiveDriving

Simulator

83

Categories

on humans

Experiment on

simulator

Humans' and agents'

behaviors clustering

Habits

Human'

categories clustering

Abstraction

Human

clusters

Agents

clusters

Humans' and agents’

annotations clustering

Annotations

on agents

and humans

Human

participant

Behavioral

questionnaire

Replays

Annotations

Logs

1

2

Agent

Figure 1: An architecture for behavior analysis and evaluation.

tion errors, but it can also be due to a too small

participants sample.

3. Those consisting of participants only; they corre-

spond to behaviors that have not been replicated

by the agents, and are thus either lacks in the

agent’s model, or due to a too small agents sample

in the parameter space.

3.2 Case Study

In the end, we combine this agent-human compari-

son with the annotation-habits analysis: The partici-

pants’ behavior clusters are correlated to their habits

categories. Furthermore, the composition of the be-

havior clusters in term of simulated agents and par-

ticipants allows us to give explicit information about

those agents.

Our method was tested in the context of driv-

ing simulators. We want to evaluate the realism and

credibility of the behavior of the IFSTTAR’s road

traffic simulator’s agents (see Figure 2) by using

the ARCHISIM driving simulator (Champion et al.,

2001). To do this, the participants drive a car on a road

containing simulated vehicles. The circuit (shown in

Figure 3) provides a driving situation on a single car-

Figure 2: Driving simulator device with 3 screens, steering

wheel, gearbox and a set of pedals.

riage way with two lanes in the same direction. It

corresponds to about 1 minute of driving. The main

actor encounters a vehicle at low speed on the right

lane.

Figure 3: Scenario: The main actor (in black) is driving on

a single carriage way with two lanes in the same direction

with a smooth traffic flow. Then, a vehicle at low speed on

the right lane (in dark gray) disturbs the traffic.

Our method is illustrated in the following sections

with this application to the study of driving behavior.

However, the presented method may be used in any

kind of participatory simulation, by choosing relevant

task-related questionnaires.

4 DATA PROCESSING METHOD

In this section, we detail the different elements of our

behavioral validation method and the algorithms that

we use.

4.1 Clustering of Main Actors

Categories

We first describe the habits questionnaire and the an-

notations questionnaire applied to the driving simula-

tion, and then detail the clustering algorithm.

4.1.1 Participants Habits

In the first place it is necessary to submit a behavior

questionnaire specific to the field before the experi-

ment to characterize the general behavior of the par-

ticipant in the studied activity. In the context of our

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

84

application to driving simulators, we chose the Driv-

ing Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ) (Reason et al.,

1990). It provides a general score, but also scores on

5 subscales: 1) slips; 2) lapses; 3) mistakes; 4) un-

intended violations; and 5) deliberate violations. In

addition, it supplies 3 subscales related to the accident

risk: 1) no risk; 2) possible risk; and 3) definite risk.

4.1.2 Annotation of Main Actors Behaviors

An adopted behavior in a precise situation may not

correspond to the participant’s general behavior. For

example, in driving simulators, the general driving

behavior captured by the DBQ may not correspond to

the participant’s behavior in the precise studied situa-

tion. Furthermore, the general behavior questionnaire

is completed by the driver himself about his own be-

haviors. This adds a bias due to introspection.

This is why we need to use a second questionnaire

called annotations. This questionnaire is completed

by a different set of participants. It avoids the in-

trospection bias. Furthermore, having a population

which is observing the situation allows us to collect

situation specific information. The questions are rated

on a Likert-type scale (Likert, 1932). In our applica-

tion to driving simulators, the questionnaire contains

a question rated on a 7 points scale (and no opinion)

from no to yes for each of the 5 DBQ subscales.

The 3 risk-related subscales are merged in a

unique question named accident risk rated on a 3

points scale (and no opinion). We also add a question

related to the perceived control on the same 7 points

scale with the purpose of evaluating the main actors

control in general. At last, a question asking if the

main actor is a human or a simulated agent is added in

order to compare how the behavior clustering and the

annotators separated the participants from the agents.

4.1.3 From Data to Categories

In the general case (independently from the applica-

tion domain), using behavior questionnaires, we ob-

tain qualitative data on Likert-type scales. The an-

swers are transformed into quantitative data via a lin-

ear numeric scale. Scale scores of questionnaires are

then calculated by adding the scale-related questions,

and normalized between 0 and 1. Once data are pro-

cessed, we classify the participants’ scores using a

clustering algorithm to obtain drivers categories. This

allows us to obtain clusters corresponding to partici-

pants’ habits and how they are annotated. As seen in

section 3.1, the algorithm must be unsupervised with

a free number of clusters. Several algorithms exist

in the literature to this purpose, such as Cascade K-

means with the Variance Ratio Criterion (Calinski-

Harabasz) (Cali

´

nski and Harabasz, 1974), X-means

based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (Pel-

leg et al., 2000), or Self-Organizing Maps (Kohonen,

1990).

We chose to use the Cascade K-means algorithm

which executes several K-means for K ∈ {1,... ,N}.

The classic K-means algorithm uses K random ini-

tial centroids. It then proceeds those two steps alter-

natively until convergence: 1) The assignment step

which assigns each main actor ma to the cluster C

i

whose mean yields the least within-cluster sum of

squares m

i

at time t (see Equation (1)); 2) The up-

date step which calculates the new means m to be the

centroids of the main actors in the new clusters at time

t + 1 (see Equation (2)).

∀ j ∈ {1, ...,k}

C

(t)

i

=

ma

p

:

ma

p

− m

(t)

i

2

≤

ma

p

− m

(t)

j

2

(1)

m

(t+1)

i

=

1

|C

(t)

i

|

∑

ma

j

∈C

(t)

i

ma

j

(2)

The initialization of the clusters is done with K-

means++ (Arthur and Vassilvitskii, 2007) which al-

lows a better distribution of clusters’ centers in accor-

dance with the data. To do so, the centroid of the first

cluster is initialized randomly among the main actors.

Until having K clusters, the algorithm computes the

distance of each main actor to the last selected cen-

troid. Then, it selects the centroid of a new cluster

among the main actors. The selection is done ran-

domly according to a weighted probability distribu-

tion proportional to their squared distance.

Finally, we must select the “best” number of clus-

ters with respect to our clustering goal. This is done

using the Variance Ratio Criterion which takes into

account the inter-distance (i.e. the within-cluster er-

ror sum of squares W ) and intra-distance (i.e. the

between-cluster error sum of squares B) of the clus-

ters (Cali

´

nski and Harabasz, 1974). Let |C

k

| be

the number of elements in the cluster C

k

, C

k

be the

barycenter of this cluster and C be the barycenter of

all main actors (i.e. the clustering). Then, the Vari-

ance Ratio Criterion CH for K clusters is as described

bellow (in Equation (3)):

CH(K) =

B/(K − 1)

W /(N − K)

(3)

B =

K

∑

k=1

|C

k

|kC

k

− Ck

2

W =

K

∑

k=1

N

∑

n=1

kma

k,n

−C

k

k

2

AMethodforSemi-automaticExplicitationofAgent'sBehavior-ApplicationtotheStudyofanImmersiveDriving

Simulator

85

4.2 Clustering of Behaviors

This section describes how raw data logs are turned

into clusters, within a series of pre-processing and

clustering methods. The figure 4 shows the pre-

processing applied to the logs in order to obtain clus-

ters. Squares indicate the data name and its shape with

the number of variables (X), the number of indicators

(K), the number of main actors (N), and the time (T ).

The used algorithms are in squircles above arrows.

The section 4.2.1 (on the top of the figure) describes

the logs of the main actors; the section 4.2.2 (on the

middle of the figure) explains the pre-processing; and

the section 4.2.3 (on the right of the figure) explains

the clustering algorithm.

Indicators

K x N x T

Mean

K x N

Coords

K x N

Clustering

Std

K x N

DTWs

K x N x N

Coords’

K’ x N

Experts

K-means

PCA

MDS

DTW

Logs

X x N x T

RMS

K x N

Figure 4: Logs pre-processing and clustering.

4.2.1 Main Actors Logs

During the simulation we collect the logs of the main

actor (participant or agent), of neighboring agents and

of the environment. These logs are then used for the

clustering of tactical and strategic behaviors. The data

to be recorded must be defined by experts in the do-

main of application.

In our traffic simulation example, we collect each

300 ms from 8 to 13 variables. The variables shared

by all the main actors are the time, the milepost, the

road, the gap and the cap to the lane axis, the speed,

the acceleration, and the topology. Specific variables

to the driven vehicles are added: the wheel angle, the

pressure on pedals (acceleration, brake and clutch),

and the gear.

The road traffic experts chose the following in-

dicators: some high-level variables like the inter-

vehicles distance and time, the jerk (the derivative of

acceleration with respect to time), the time to collision

(under the assumption of constant speeds for both ve-

hicles), and the number of lane changings (which is

not a temporal indicator) ; as well as some low-level

variables such as speed, acceleration, and lateral dis-

tance to the road axis.

4.2.2 Pre-processing

Some significant indicators dependent on the applica-

tion field cannot be directly obtained. For this reason,

field experts are consulted to identify important indi-

cators. Then we calculate the indicators from the logs

for those that could not be collected.

In the context of a dynamic simulation, most of

the indicators are temporal. The data to classify are

thus ordered sequences of values for each main ac-

tor. In order to classify those data, two ways exist:

to use an algorithm taking temporal data as input or

to use flat data by concatenating temporal indicators

related to a participant on a single line. The first solu-

tion significantly increases the algorithms’ complex-

ity because they must take into account the possible

temporal offsets of similar behaviors. The second one

ignores temporal offsets but permits the application of

classic algorithms.

We chose a hybrid solution of data pre-processing

which allows us both to have a single set of attributes

for each participant and to take into account tempo-

ral offsets. To do this, we generate as many vec-

tors as main actors (participants and virtual agents).

Each vector contains the following information ex-

tracted from the indicators identified by the field ex-

perts: a) mean values; b) standard deviations; c) root

mean squares; and d) temporal aggregations. Tempo-

ral indicators are compared with an algorithm taking

into account temporal offsets.

The adopted solution for the pre-processing of

temporal offsets is to use a pattern matching algorithm

such as Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) or Longest

Common Subsequence (LCS). We chose the DTW al-

gorithm which calculates the matching cost between

two ordered sequences (i.e. indicators ind

a

and ind

b

)

in order to measure their similarity (Berndt and Clif-

ford, 1994). Let T be the number of simulation time

steps. The algorithm computes a T × T matrix. It

initializes the first row and the first column to infin-

ity, and the first element to 0. It then computes each

elements of the matrix M

i, j

∀(i, j) ∈ {2,..., T + 1}

2

according to the distance between the two sequences

at this time t and to the matrix element neighborhood

(see Equation (4)). As DTW complexity is O(N

2

), we

use an approximation of this algorithm: the FastDTW

algorithm which has order of O(N) time and memory

complexity (Salvador and Chan, 2007).

DTW [i, j] ← distance(ind

a

i

,ind

b

j

)+ (4)

min(DTW [i − 1, j], DTW [i, j − 1],DTW [i − 1, j − 1])

As DTW calculates the similarity between two in-

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

86

stances of a temporal variable, the less the instances

are similar, the more the cost increases. Let inds be

the set of indicators and K = |inds| be the number of

indicators. For each indicator ind ∈ inds, we calculate

the N × N mutual distances matrix D

ind

DTW

, where N is

the number of main actors (participants and agents).

In order to include DTW similarities as new vari-

ables describing the main actors, we use a Multi-

Dimensional Scaling algorithm (MDS) to place each

main actor in a dimensional space. The algorithm

assigns a point to each instance in a multidimen-

sional space and tries to minimize the number of

space dimensions. The goal is to find N vec-

tors (coord

1

,. .., coord

N

) ∈ R

N

such that ∀(i, j) ∈

N

2

,kcoord

i

− coord

j

k ≈ D

ind

DTW

(i, j).

As DTW is a mathematical distance, the MDS al-

gorithm applied to each D

DTW

is able to minimize the

number of space dimensions to 1 (i.e. a vector of co-

ordinates). Then we have as many vectors of coordi-

nates as indicators.

Indicators’ coordinates may be correlated among

each others but the K-means algorithm uses a dimen-

sional space of which the axes are orthogonal to each

other. In order to apply this algorithm, we need to

project the data on an orthogonal hyperplane of which

the axes are two by two non-correlated.

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) calcu-

lates the non-correlated axes which give a maximal

dispersion of the data. It is then possible to reduce

the number of dimensions avoiding redundant infor-

mation by compressing them. Data are represented

in a matrix of coordinates C with K random vari-

ables {ind

1

,. .., ind

K

} containing N independent real-

izations. This matrix is standardized according to the

center of gravity

ind

1

,. .., ind

K

(with ind the arith-

metic mean) and to the standard deviation σ of the

random variables. It is then possible to calculate the

correlation matrix:

1

N

·

e

C

T

·

e

C. The PCA looks for the

axis u which maximizes the variance of the data. To

do so, it calculates a linear combination of the ran-

dom variables in order to project the data on this axis:

π

u

(C) = C · u. We keep the same number of axes K

0

for the projected indicators as for the indicators (K).

e

C =

ind

1,1

−ind

1

σ(ind

1

)

·· ·

ind

1,K

−ind

K

σ(ind

K

)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

ind

N,1

−ind

1

σ(ind

1

)

·· ·

ind

N,K

−ind

K

σ(ind

K

)

(5)

4.2.3 Behavior Clusters

Finally, we apply on the PCA projected indicators the

same K-means algorithm as the one applied on the

questionnaire’s scores in order to classify these data

(normalized between 0 and 1). We thus obtain behav-

ior clusters of main actors, as shown in Figure 4.

4.3 Clusterings Comparison

Now that we have annotations clustering, behaviors

clustering on main actors and habits clustering on par-

ticipants, we want to compare the clusters composi-

tion between the annotations and the behaviors, and

between the habits and the behaviors.

As we want to compare clusterings, we need a

similarity measure between two clusterings C

1

and

C

2

. We use the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) (Hu-

bert and Arabie, 1985) - a well known index recom-

mended in (Milligan and Cooper, 1986) - which is

based on pair counting: a) N

00

: the number of pairs

that are in the same set in both clusterings (agree-

ment); b) N

11

: the number of pairs that are in dif-

ferent sets in both clusterings (agreement); and c) N

01

and N

10

: the number of pairs that are in the same set

in one clustering and in different sets in the other (dis-

agreement) and vice-versa. The Rand Index RI ∈ [0, 1]

is described in Equation (6) (Rand, 1971). The Ad-

justed Rand Index ARI ∈ [−1, 1] is calculated using

a contingency table [n

i j

] where n

i j

is the number of

agreements between instances i and j: n

i j

= |C

i

1

∩C

j

2

|

(see Equation (7)). It is a corrected-for-randomness

version of the RI: Where the expected value of RI for

two random clusterings is not constant, the expected

value of ARI is 0.

RI(C

1

,C

2

) =

N

00

+ N

11

N

00

+ N

11

+ N

01

+ N

10

(6)

ARI(C

1

,C

2

) =

RI(C

1

,C

2

) − E [RI(C

1

,C

2

)]

1 − E [RI(C

1

,C

2

)]

(7)

where

E [RI(C

1

,C

2

)] =

"

∑

i

∑

k

n

ik

2

∑

j

∑

l

n

l j

2

#

/

n

2

5 EXPERIMENTATION

The participants to our driving simulation experiment

are regular drivers aged from 24 to 59 (44% female).

Our experiment is carried out on a device compris-

ing a steering wheel, a set of pedals, a gearbox and

3 screens allowing sufficient lateral field of view (see

Figure 2). These screens are also used to integrate the

rear-view mirror and the left-hand mirror. 23 partici-

pants used this device.

Firstly, the Driver Behavior Questionnaire is sub-

mitted before the simulation. Secondly, a first test

AMethodforSemi-automaticExplicitationofAgent'sBehavior-ApplicationtotheStudyofanImmersiveDriving

Simulator

87

without simulated traffic is performed for the partici-

pant to get accustomed to the functioning of the sim-

ulator and to the circuit. Then, the participant per-

forms the scenario, this time in interaction with simu-

lated vehicles. It should be noted that as the behavior

of simulated vehicles is not scripted, situations differ

more or less depending on the main actor behavior.

The data are then recorded for the processing phase.

A video is also made for the replay. Finally, another

population of 6 participants fills the annotations ques-

tionnaire after viewing the video replay of the simula-

tion in order to evaluate the adopted behaviors of the

main actors (i.e. 23 participants and 14 agents).

One participant had simulator sickness but was

able to finish the experiment, and one annotator had

dizziness and ceased watching.

5.1 Results

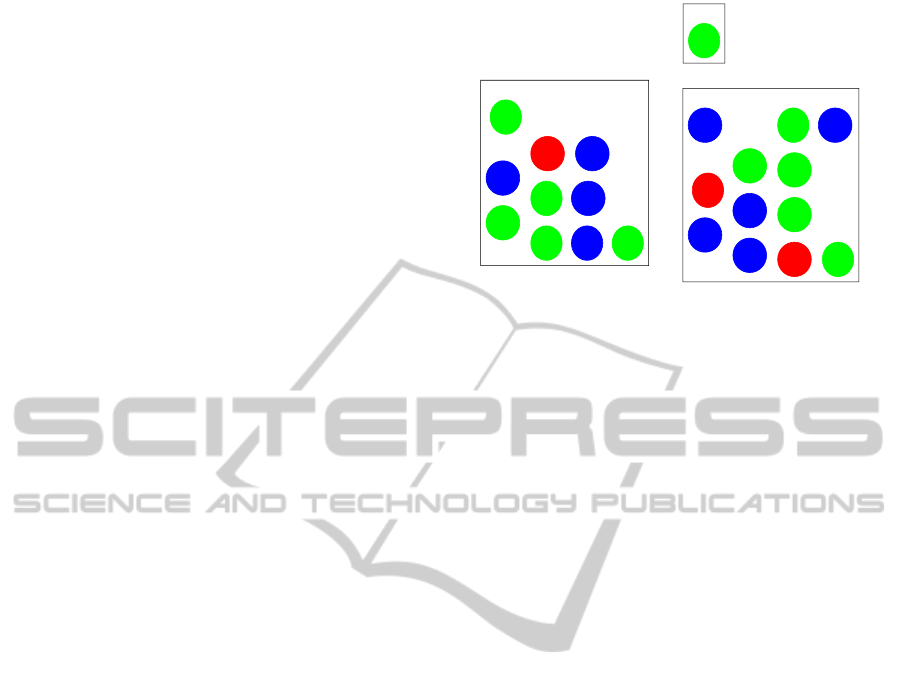

We have compared the habits clustering, the anno-

tations clustering, and the behaviors clustering. The

composition of the clusterings is illustrated with three

graphs. Agents are represented with rectangles and

are named a#. Participants are represented with el-

lipses and are named s#. The main actors of one clus-

tering are grouped together within rectangles contain-

ing the cluster number on the top. The others cluster-

ing’s main actors are grouped together by color and

the cluster number is written just bellow the main ac-

tors names.

5.1.1 Habits & Annotations Clusters

We want to compare the DBQ scales and the summa-

rized DBQ scales of our annotations questionnaire.

The figure 5 shows the habits clustering (within rect-

angles) and the annotations clustering (grouped to-

gether by color), and their similarity. As the habits

clustering from the DBQ questionnaire is only filled

by simulation participants, we do not display the

agents from the annotations clustering. The habits

clustering contains 3 clusters which are close to the 2

clusters of the annotations clustering. cluster1 con-

tains nearly all participants of the cluster (1) (ex-

cepted s12). cluster2 is composed of cluster (2) par-

ticipants only. Also, cluster3 is mainly composed of

cluster (2) participants (excepted s17). The rand in-

dex is 0.71 and the adjusted rand index is 0.42. This

means that our summarized DBQ scales in the an-

notations questionnaire is meaningful with regard to

driver behavior habits.

cluster1

cluster2

cluster3

s1

1

s12

2

s13

1

s3

1

s4

1

s5

1

s6

1

s8

1

s9

1

s16

2

s2

2

s21

2

s23

2

s10

2

s11

2

s14

2

s15

2

s17

1

s18

2

s19

2

s20

2

s22

2

s7

2

Figure 5: Comparison of participants between habits

clustering (within rectangles) and annotations clustering

(grouped together by color).

cluster1

cluster2

cluster3

a1

1

a10

1

a11

2

a12

2

a13

1

a14

1

a2

2

a3

1

a4

1

a6

1

a7

1

a8

1

a9

1

s9

1

s1

1

s11

1

s17

2

s18

2

s19

1

s21

2

s4

1

s6

1

s7

2

s8

1

a5

2

s10

2

s12

2

s13

1

s14

2

s15

2

s16

2

s2

2

s20

2

s22

2

s23

2

s24

2

s25

2

s3

1

s5

1

Figure 6: Comparison of main actors between behav-

ior clustering within rectangles and annotations clustering

grouped together by color.

5.1.2 Behavior Clusters & Annotations Clusters

With the behavior clustering on main actors, we are

able to analyze how many human behaviors are re-

produced by the agents, how many human behaviors

are not adopted by the agents, and how many agent

behaviors are not adopted by participants. We are

also capable of making explicit those behaviors via

the similarity with annotations clusters if relevant.

The figure 6 presents the behaviors clustering

(within rectangles) and the annotations

1

clustering

grouped together by color. The number of clusters is

1

Except for the human or simulated agent question

which is not related to the adopted behavior.

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

88

similar in both clusterings (3 behaviors versus 2 types

of annotations). The rand index is 0.59 and the ad-

justed rand index is 0.17.

• cluster1 contains one participant and nearly all

the agents (excepted a5). Most of its main ac-

tors are annotated in the same way (i.e. in cluster

(1)). So, the main actors of the cluster 1 adopted

a similar driving behavior and were annotated in

the same way, i.e.: the highest score on perceived

control question and the lowest scores on the other

questions. Therefore, they are judged as careful

drivers.

• cluster2 is only composed of participants which

are mixed between the two annotations clusters.

• cluster3 is mainly composed of participants (and

the agent a5). Those participants are largely anno-

tated in the same cluster (2), which has the lowest

score on the perceived control question and the

highest scores on other questions, meaning that

they are judged as unsafe drivers.

5.1.3 Behavior Clusters & Habits

We have compared the drivers habits using the DBQ

questionnaire with the adopted behavior. As the

habits clustering from the DBQ questionnaire is only

filled by simulation participants, we do not displayed

the agents from the annotations clustering. The Vari-

ance Ratio Criterion selects 3 clusters. The rand in-

dex is low (0.48) as is the adjusted rand index (0.07).

The clustering contains a singleton cluster and two

other clusters, each containing a mixture of all the

DBQ clusters, meaning that the behavior clustering

does not correspond to the habits clustering. It vali-

dates the use of annotations by observers, which are

closer to data clustering results.

5.2 Discussion

Firstly, there is no significant similarity between

habits clustering and behaviors clustering. This might

be due to the general approach of the DBQ question-

naire. The driver’s habits may differ from the adopted

behavior. The DBQ is filled by the driver itself. The

introspection bias may be the reason of the differ-

ences. This is also an issue for us because we cannot

apply it to the agent. The 3 scales dealing with the risk

could be another problem: 8% of the participants had

some high scores on the No risk scale and the Definite

risk scale but a low score one the Possible risk scale.

Another problem is that the same type of participant

in term of DBQ cluster can adopt different behaviors

for the same situation, leading to different logs. Sim-

ilarly, the same behavior can be adopted by different

cluster1

cluster2

cluster3

s9

2

s1

2

s11

3

s17

3

s18

1

s19

3

s21

2

s4

2

s6

2

s7

3

s8

2

s10

3

s12

2

s13

2

s16

2

s2

1

s20

3

s22

3

s23

3

s24

3

s25

1

s3

2

s5

2

Figure 7: Comparison of main actors between behavior

clustering within rectangles and habits clustering grouped

together by color.

types of participants. This is an issue to analyze the

similarity between the habits clustering and the be-

haviors clustering with the ARI measure. A solution

could be to merge the subsets for which all main ac-

tors are also in the same cluster in the other clustering.

Secondly, we have a significant similarity between

annotations and behavior clusterings, meaning that

we are able to classify our logs data into high-level be-

havior clusters which are meaningful in term of driv-

ing annotations. Nevertheless the two clusterings are

not identical with regard to the clusters composition

nor with regard to the clusters number. This could be

due to the few number of annotators, we are currently

increasing this population. Furthermore, the behav-

ior clustering is done on noisy indicators for human

participants and on smooth indicators for agents. A

solution might be to add a noise on the agents data

or to smooth the participants data. This problem may

come from the clustering algorithm which is a classic

but basic one. We have to test with advanced algo-

rithms like EM or a temporal algorithm.

In the comparison of annotations and behaviors,

one agent was in a mainly human composed cluster.

Does this mean that it is able to simulate the majority

of driver’s behaviors of this cluster which is cautious

? If it is, we can then consider that this cautious be-

havior is an agents ability. To verify this assumption,

we would need a specific test in which the parame-

ter set that was used for the agent a5 is confronted to

different situations, and compared with logs and an-

notations of cautious human drivers. Conversely, one

participant was in the mainly agent composed cluster

judged as dangerous for a majority of them. This re-

quires further study to understand what was specific

in this subject’s driving behavior that was similar to

the agents’ behaviors. cluster2 does not contain any

agent, meaning that the agent’s model is not able to

reproduce this human driving behavior (i.e. this be-

AMethodforSemi-automaticExplicitationofAgent'sBehavior-ApplicationtotheStudyofanImmersiveDriving

Simulator

89

havior is lacking in the agent’s model). Another type

of cluster - which does not appear in this experiment -

is composed of agents only. In that case, we can con-

sider - as no participant adopted this behavior - that

the agents behavior is inaccurate (i.e. is an error) and

should be investigated further.

6 CONCLUSIONS &

PERSPECTIVES

This paper presents a method to study the agents’ be-

havioral credibility through an experiment in a virtual

environment. This validation is original in coupling

a subjective analysis of the agents’ behavioral credi-

bility (via human sciences questionnaires and annota-

tions) with an objective analysis of the agents’ abil-

ities. This analysis is based on behaviors clustering

which allows us to obtain behaviors categories at a

higher level than raw data. The method is generic

for mixed simulation where agents and humans inter-

act. When applied to a new domain, some of the tools

have to be adapted, such as the choice of the behavior

questionnaire which is domain-specific. The method

is fully implemented, built on the Weka toolkit. The

software shall be made available in the future.

Our validation method was applied to the road

traffic simulation. This experiment showed that the

methodology is usable for mixed and complex VEs

and that it is possible to obtain high-level behaviors

from the logs via our abstraction. A larger annota-

tors population should provide more evidence of the

method’s robustness.

Several tracks for further work remain to explore.

On the clustering part, the evaluation of multiple algo-

rithms should enable to better assess their relevance.

To do so, the use of the results of the comparison

between annotations clusters and observed behavior

clusters allows us to choose the most pertinent algo-

rithm depending on the application. Another research

open issue - as annotation are similar to behaviors

whereas habits differ - is how the behaviors cluster-

ing evolve through multiple situations of a longer sce-

nario, whether the participants clusters remain stable

or change in number or composition.

REFERENCES

Arthur, D. and Vassilvitskii, S. (2007). k-means++: The

advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the

eighteenth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete

algorithms, pages 1027–1035. Society for Industrial

and Applied Mathematics.

Berndt, D. and Clifford, J. (1994). Using dynamic time

warping to find patterns in time series. In KDD work-

shop, volume 10, pages 359–370.

Burkhardt, J. M., Bardy, B., and Lourdeaux, D. (2003). Im-

mersion, r

´

ealisme et pr

´

esence dans la conception et

l’

´

evaluation des environnements virtuels. Psycholo-

gie franc¸aise, 48(2):35–42.

Caillou, P. and Gil-Quijano, J. (2012). Simanalyzer: Auto-

mated description of groups dynamics in agent-based

simulations. In Proceedings of the 11th Interna-

tional Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-

agent Systems-Volume 3, pages 1353–1354. Interna-

tional Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multi-

agent Systems.

Cali

´

nski, T. and Harabasz, J. (1974). A dendrite method for

cluster analysis. Communications in Statistics-theory

and Methods, 3(1):1–27.

Champion, A.,

´

Espi

´

e, S., and Auberlet, J. M. (2001). Be-

havioral road traffic simulation with archisim. In Sum-

mer Computer Simulation Conference, pages 359–

364. Society for Computer Simulation International;

1998.

Champion, A., Zhang, M. Y., Auberlet, J. M., and Espi

´

e, S.

(2002). Behavioral simulation: Towards high-density

network traffic studies. ASCE.

Drogoul, A., Corbara, B., and Fresneau, D. (1995). Manta:

New experimental results on the emergence of (artifi-

cial) ant societies. Artificial Societies: the computer

simulation of social life, pages 190–211.

Fontaine, G. (1992). The experience of a sense of pres-

ence in intercultural and international encounters.

Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments,

1(4):482–490.

Gonc¸alves, J. and Rossetti, R. J. F. (2013). Extending

sumo to support tailored driving styles. 1st SUMO

User Conference, DLR, Berlin Adlershof, Germany,

21:205–211.

Hubert, L. and Arabie, P. (1985). Comparing partitions.

Journal of classification, 2(1):193–218.

Javeau, C. (1978). L’enqu

ˆ

ete par questionnaire: manuel

`

a

l’usage du praticien. Editions de l’Universit

´

e de Brux-

elles.

Kohonen, T. (1990). The self-organizing map. Proceedings

of the IEEE, 78(9):1464–1480.

Leplat, J. (1997). Simulation et simulateur: principes et us-

ages. Regards sur l’activit

´

e en situation de travail:

contribution

`

a la psychologie ergonomique, pages

157–181.

Lessiter, J., Freeman, J., Keogh, E., and Davidoff, J. (2001).

A cross-media presence questionnaire: The itc-sense

of presence inventory. Presence: Teleoperators & Vir-

tual Environments, 10(3):282–297.

Lester, J. C., Converse, S. A., et al. (1997). The persona ef-

fect: affective impact of animated pedagogical agents.

In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human

factors in computing systems, pages 359–366. ACM.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of atti-

tudes. Archives of psychology.

Maes, P. and Kozierok, R. (1993). Learning interface

agents. In Proceedings of the National Conference on

ICAART2014-InternationalConferenceonAgentsandArtificialIntelligence

90

Artificial Intelligence, pages 459–459. John Wiley &

Sons LTD.

McGreevy, M. W. (1992). The presence of field geologists

in mars-like terrain. Presence: Teleoperators and Vir-

tual Environments, 1(4):375–403.

Milligan, G. W. and Cooper, M. C. (1986). A study of

the comparability of external criteria for hierarchical

cluster analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research,

21(4):441–458.

Patrick, J. (1992). Training: Research and practice. Aca-

demic Press.

Pavlov, I. P. and Anrep, G. V. (2003). Conditioned reflexes.

Dover Pubns.

Pelleg, D., Moore, A., et al. (2000). X-means: Extend-

ing k-means with efficient estimation of the number

of clusters. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Inter-

national Conference on Machine Learning, volume 1,

pages 727–734. San Francisco.

Premack, D., Woodruff, G., et al. (1978). Does the chim-

panzee have a theory of mind. Behavioral and brain

sciences, 1(4):515–526.

Rand, W. M. (1971). Objective criteria for the evaluation of

clustering methods. Journal of the American Statisti-

cal association, 66(336):846–850.

Reason, J., Manstead, A., Stradling, S., Baxter, J., and

Campbell, K. (1990). Errors and violations on the

roads: a real distinction? Ergonomics, 33(10-

11):1315–1332.

Salvador, S. and Chan, P. (2007). Toward accurate dynamic

time warping in linear time and space. Intelligent Data

Analysis, 11(5):561–580.

Serrano, E., Mu

˜

noz, A., and Botia, J. (2012). An approach

to debug interactions in multi-agent system software

tests. Information Sciences, 205:38–57.

Stoffregen, T. A., Bardy, B. G., Smart, L. J., and Pagulayan,

R. J. (2003). On the nature and evaluation of fidelity

in virtual environments. Virtual and adaptive environ-

ments: Applications, implications, and human perfor-

mance issues, pages 111–128.

Witmer, B. G. and Singer, M. J. (1998). Measuring pres-

ence in virtual environments: A presence question-

naire. Presence, 7(3):225–240.

AMethodforSemi-automaticExplicitationofAgent'sBehavior-ApplicationtotheStudyofanImmersiveDriving

Simulator

91