Observational Research Social Network

Interaction and Security

Rui Pedro Lopes

1,2

and Cristina Mesquita

1

1

Polytechnic Institute of Braganc¸a, Campus St. Apol

´

onia, Braganc¸a, Portugal

2

IEETA, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords:

Preschool Education, Observational Research, Social Networks.

Abstract:

Quality in education depend heavily on the teachers’ professional development, as a mean for pedagogical

methodologies and practice improvement. In this sense, learning is enhanced by sharing and working in a

community of practice, a learning organization that generate knowledge and allow members to innovate. In

this context, children observation is fundamental, allowing a sound basis for reflection and action around

learning experiences and teaching environments. Specific guidelines and programs, such as the EEL/DQP, can

help reducing the inherent subjectivity, providing a common base for teachers and the preschool education

community. In this paper we propose an online, web based community to improve the observation process as

well as the communication between researchers. The social relations are identified and the security issues are

discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

The literature about teachers’ professional develop-

ment shows that communities of practice constitute

centers for professional growth (Sheridan et al., 2009;

Evans et al., 2006). In this sense, communities of

practice are groups of people who gather from com-

mon professional interests and a desire to improve

their practice, sharing their knowledge, ideas and ob-

servations. A community of practice can be under-

stood as a social system for learning because, like

other social systems, provide: i) a structure where

they develop complex and dynamic relationships; ii)

ongoing negotiations between members; iii) shared

meanings and cultural identity (Wenger, 2010).

In this perspective, communities of practice can

constitute itself as an opportunity for learning about

what really matters, about epistemology, ontology

and methodology that can sustain the praxis. Com-

munities of practice are conceived as learning organi-

zations which investigate their situation and their rela-

tionships and generate praxeological knowledge that

allows teachers to innovate.

The Effective Early Learning (EEL) Project

(Bertram and Pascal, 2004), known in Portugal under

the designation Desenvolvendo Qualidade em Parce-

ria – DQP (Bertram and Pascal, 2009) propose the

creation of communities that develop a collaborative

action, focused on shared purposes and in a sustained

process of pedagogical mediation by an external su-

pervisor. This intends to improve the quality of early

childhood education contexts, through an active in-

volvement of participants. It is a monitoring process

that uses several observations tools requiring that pro-

fessionals build knowledge and skills about the un-

derlying processes that allow them to reflect with the

peers about their action.

Observations in the EEL/DQP are used to assess

children physical, emotional, social, and intellectual

development, focusing on specific areas, such as so-

cial interaction, learning experiences, space manage-

ment and creations, and others. They can also help to

better understand how different areas of development

are interrelated, as well as helping recognizing what

behaviors are typical of various age groups. In turn,

this understanding will help the teacher to improve as

a person and as a professional.

Each observation process depends heavily on the

sensibility and experience of the teacher. It is very dif-

ficult to get consistent results if the observers diverge

in the way they interpret the setting. Although natural

and inherent to the process, it is important to mini-

mize this subjectivity. In order to do so, the observa-

tions are performed simultaneously by more than one

teacher in a democratic way. The external supervisor

also has a thorough perspective on the whole project

57

Pedro Lopes R. and Mesquita C..

Observational Research Social Network - Interaction and Security.

DOI: 10.5220/0004837800570064

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 57-64

ISBN: 978-989-758-022-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

and may participate in some or all observations. The

bottom line is that to be able to get meaningful in-

formation, the communication between all the teach-

ers and researchers is fundamental, as a way to foster

reasoning and action building.

In this paper we propose the design and develop-

ment of an online, web-based, regulated community,

providing:

• A central and secure repository of observation

data, results and annotations;

• A computer mediated social network.

This service allows each teacher to manage the

observation process, sharing information with autho-

rized colleagues and improving their experience and

knowledge.

2 EVALUATION PROCESS IN

EEL/DQP

The evaluation of quality of early learning in the

scope of EEL/DQP requires obtaining a considerable

amount of data through several techniques, includ-

ing detailed observations of children and adults, inter-

viewing parents, practitioners and children, documen-

tary analysis and others. This complex and somewhat

subjective process requires well-trained teachers and

researchers. In particular, the EEL/DQP initiative de-

fines a four phase/thirteen steps procedure (Figure 1).

Data is gathered and systematically organized in

research portfolios, that will be used in a cyclic pro-

cess of thinking-do-thinking to research and create

change (Mesquita-Pires, 2012). This process is en-

hanced by the utilization of observation techniques

which measure the effectiveness of the learning and

teaching processes, such as the Child Tracking Ob-

servation Schedule, to gain a snapshot of the childs

day and providing information of learning experi-

ences (Bertram and Pascal, 2006), the Child Involve-

ment Scale, an observation technique which mea-

sures the level of a childs involvement in an activity,

the Adult Engagement Scale, to evaluate the interac-

tion between the practitioner and the child (Laevers,

1994).

The application of the procedure has a broad set

of difficulties and challenges. Initially, it is neces-

sary that the research group learn about participatory

pedagogies as theoretical foundations about EEL re-

search techniques and the practicalities of their use.

The application of interviews come soon after, which

lead the participants to reflect on the ethical issues in-

volving its use. Learning to observe is another chal-

lenge, because the signs are not always evident and

Evaluation

Initial Preparation

Initial Data Gathering

Interviews

Child Tracking Observation Schedule

Child Involvement Scale

Adult Engagement Scale

Development of Evaluation Report

Action Planing

Development of the Action Plan

Development

Document and implementation of the action plan

Child Tracking Observation Schedule

Child Involvement Scale

Adult Engagement Scale

Reflection

Reflection on the impact of the plan in the future

Final Report

Figure 1: EEL/DQP phases and steps.

observers must be well trained to identify them. Be-

sides, the observation process should be systematic

requiring that kindergarten teachers find time in their

daily routine to observe the children and understand

how they are learning.

2.1 EEL/DQP Procedure

The EEL/DQP overall procedure follows the four

phases described above. It starts by an initial orien-

tation of the work to be performed, in which all the

process is prepared and all the participants informed

in detail. Initial data gathering follows, where the in-

stitution is characterized, including the interior and

exterior spaces, its education philosophy, the differ-

ent learning activities, and others.

The third step includes performing interviews to

the dean, staff (about 50 %), children (20%), and par-

ents (20%). It is very important that all the stake-

holders are well informed and understand the process.

The teacher records the interviews and take notes of

key phrases, to support the written report. In the end,

access to interview transcripts must be given to par-

ticipants.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

58

The fourth step requires an observation process,

using the Child Tracking Observation Schedule, with

the main purpose of understanding the child’s daily

routine. This technique gives information about the

learning experiences, the level of choice, his involve-

ment, the group organization and interaction with

adults.

The Child Involvement Scale seeks to measure

not only the learning outcomes but also the under-

lying processes. Essentially, it gathers information

about the participation in activities and projects, thus

giving indicators of concentration and motivation as

well as of satisfaction (Laevers, 2005). When lack-

ing, chances are that the children development will

stagnate, and all the actors in the education process

should do everything in order to create an environ-

ment in which children can engage in a wide variety

of activities. The details are registered in a specific

form.

The Adult Engagement Scale evaluates the inter-

action between the practitioner and the child (Laev-

ers, 1994). It targets the effectiveness of the teaching-

learning process through observation of adult-child

interaction. The quality of the adult’s intervention is a

critical factor for the child’s knowledge building. Up

to a maximum of 5 adults should be observed, paying

special attention to the sensibility, stimulation and au-

tonomy categories.

2.2 Ethical Behavior

Ethical behavior is fundamental in the whole process,

since it tackles professional behavior, privacy, and

confidentiality concerns (always keep in mind that the

observer is representing his school as well as himself).

Children, parents and professionals should be treated

with courtesy, always respecting the privacy rights of

children and family.

All the participants in the project, including chil-

dren, should be informed about all the details of the

project and their role in the whole process, giving

their consent. This will ensure that all of them are

comfortable and willingly, contributing to better re-

sults.

During observations, teachers may gather sensi-

tive information, such as details about child’s devel-

opment and behavior, as well as videos or pictures.

Children and their parents must know that this data is

restricted and will not be used in other contexts. Even

with adequate permission to observe and record these

details, the information must be stored appropriately,

to avoid misuses and eavesdropping.

2.3 Community Use Case

The procedure described in the previous sections is

traditionally paper-based, requiring a lot of written

material. In a typical set of 24 children, of which only

50% are observed, as much as 48 to 72 pages of forms

are filled. In a kindergarten, this procedure is repeated

in all the rooms, totaling more than 200 pages of gath-

ered data. Moreover, all the visual and audio details

are lost.

The subjectivity inherent to this process also re-

quires that all the observers, usually the kindergarten

teachers, receive an uniform training, allowing them

to achieve similar interpretations of similar situations.

This is only possible if the communication between

them is open and regular, requiring several in person

meetings.

Moving this information to an online service, such

as a social network, will allow the observers to store

and organize all the observation data in a single pro-

file, combining video, audio and text data in the same

observation procedure. This also makes it possible

to communicate asynchronously with other observers,

providing a valuable tool for subjectivity reduction

and better overall learning.

3 THE TEOBS SOCIAL

NETWORK

The interactions between observers (kindergarten

teachers) is fundamental to provide a stimulating en-

vironment for reflection and discussion, essential to

ensure low levels of subjectivity and to improve ob-

servers’ skills. The EEL/DQP process expects sev-

eral, face-to-face, meetings to discuss about the data

gathered in all of its steps.

The social relationships established between the

participants in this process (friendship, co-working,

information exchange, . . . ) can be mediated by com-

puters through the TeObs social network. Computer-

mediated communication (CMC) gives the possibil-

ities for asynchronous exchange of information, re-

gardless of where participants are. The community is

no longer defined as a physical place, but as a set of

relationships where people interact socially for mu-

tual benefit (Garton et al., 2006). However, this does

not preclude face-to-face meetings, should the com-

munity decide accordingly.

MySpace, Facebook or Twitter are remarkable ex-

amples of social networks, connecting millions of

people around the world. TeObs intends to be an audi-

ence specific social network, connecting kindergarten

teachers and providing a constantly updated memory

ObservationalResearchSocialNetwork-InteractionandSecurity

59

of experiences and previous knowledge. This can re-

sult in connections between individuals that would

not be made otherwise and that can prove valuable

for the overall process as well as for each participant

training (Boyd and Ellison, 2007).

3.1 Social Interactions

TeObs is a web-based service that allow individuals

to construct a public or semi-public profile within a

community. Connections among participants are ar-

ticulated through a list of other users, keeping in mind

the ethical behavior and security concerns. Under this

restrictions, each user is allowed to traverse their list

of connections and those made by others within the

system.

Each user can be in two broad status:

• Idle: the user is not currently participating in an

observation project, having access to specific con-

nections and to previous notes and contents;

• Active: the user is participating in an observation

project, with mandatory connections to peers and

to the external advisor (the supervisor).

Each role the user can have is associated to his

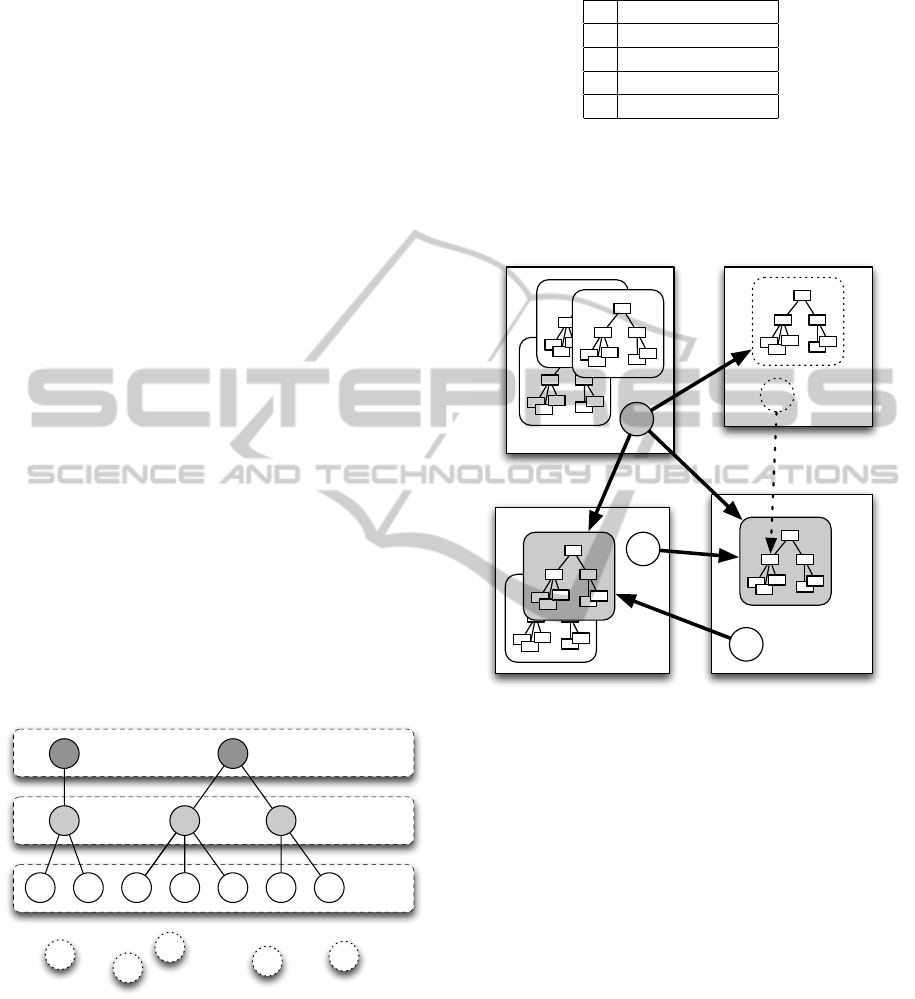

experience level (Figure 2). The bottom layer is

populated with members unable to perform observa-

tions without undergoing a training process – dot-

ted circles. After acquiring basic skills, the member

gets the observer status, able to perform observations

autonomously (as long as following the predefined

guidelines).

Observers

Local supervisor

Supervisor

Figure 2: Community.

With increasing experience, the status may be el-

evated to experienced observer and, later on, to local

supervisor. Finally, with complete domain of the ob-

servation process and with several successful projects,

the teacher can become a full supervisor (Table 1).

An observation process starts with a supervisor

creating a community and adding a number of kinder-

garten teachers. Usually, the community corresponds

Table 1: Observer level.

4 Supervisor

3 Local Supervisor

2 Experienced

1 Basic training

0 No training

to an institution, although it is not mandatory. Next,

the supervisor establishes the relationship between

the community elements, granting or removing access

to the data collected by each observer (Figure 3).

S

A

B

C

Figure 3: Social relations in an observation process.

Each observer, identified by a circle, collects and

organizes information, stored in his personal area (the

large rectangle). The observation data is structured as

a tree, enclosed in a round rectangle. Each observer

has full access to his area and all the data elements

within. To reduce subjectivity, it is important that the

data is shared with a peer and with a supervisor, to

ensure similar criteria among observers. Sharing is

configured by the supervisor, granting access to some

information. In figure 3, the supervisor ‘S’ has access

to the current procedure (gray round rectangles), the

observer ‘A’ has access to the data collected by ‘B’

and vice-versa.

Each observer can also have data from previous

procedures (white round rectangles). This is private

information and is only shared with the supervisor

and the observers of the same community at that time

– ‘B’ and ‘S’ may not have access to it.

When starting a new community, the supervisor

can invite a non-trained observer (dotted shapes in the

figure). He is not able to contribute with observation

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

60

data without acquiring basic skills so, the first step is

to go through a training process. Other than “brick-

and-mortar” training, observer ‘C’ may have access

to specific data from other observations, granted by

the supervisor, as well as other materials. He must

be familiar with the team members, their perspectives

and pedagogical practices so that among peers could

be developed positive interactions.

The data, the social relations as well as the ex-

perience level is instantiated in a web-based, online

application, which we call TeObs.

4 STRUCTURE AND

IMPLEMENTATION DETAILS

TeObs is built in Java Enterprise Edition, following

an multitier architecture structured in three functional

layers (Figure 4):

• Data Model – responsible for data persistence and

structure;

• Business Layer – library of actions available to

upper layers and external applications, such as

web browser, smartphone or desktop user inter-

face;

• Web Layer – Web browser interface with the user.

Data Access

JDBCJDBC

BusinessEJB EJB EJB

Web Services JSF JSF JSF

iOS

Android

Web Browser

JSON

HTML

Figure 4: Multitier architecture.

Each layer is self contained, allowing the encap-

sulation of functionality and the distribution of re-

sources to better cope with peak usage patterns or the

increase of the number of users. This approach al-

lows to build large-scale, scalable, reliable, and secure

applications as well as simplifying the development

of complex, distributed applications. The existence

of a representational state transfer (REST) communi-

cations API allows integrating external applications,

running in smartphones, for example (Mesquita-Pires

and Lopes, 2014).

4.1 Data Management

As mentioned above, the observation process in the

EEL/DQP project is implemented in three proce-

dures: the Child Tracking Observation Schedule, the

Child Involvement Scale and the Adult Engagement

Scale. The observation details are registered in forms,

structured according to the type and nature of each

field. The EEL/DQP defines several fields, such as

the institution and the observer name, the date, time,

and the child’s name, sex and age. In addition it also

records the number of children and adults present dur-

ing the session, the child’s level of initiative (1 to

4), learning experiences, involvement (1 to 5) and in-

teraction, among others (Mesquita-Pires and Lopes,

2014).

At a macro level, the procedure is structured hi-

erarchically, in which an observation has several ses-

sions and each session has many activities. Consid-

ering the structure and the nature of each data field

as well as the associations between data entities, the

structure of information in this situation is represented

as five entities (Figure 5). The AES prefix indicates

Adult Engagement Scale specific data.

AESSession

AESObservation

Community Observation

*

1

SharedKey

User

1

1

Session

*

1

*

1

Activity

*

1

ACL

*

1

*

1

Figure 5: Entity diagram.

4.2 User Management

All the actions and data in the TeObs Social Network

are associated to and belong to a specific user. In this

context, users represent human agents that use a net-

work service. He has to be identified, through a user-

name, and authenticated using a password. This in-

formation is organized in specific entities (Figure 6).

The password is stored in the database in the form

of a unidirectional hash, so that even if the password

table is compromised, the attacker will not be able

to decipher it. The entity Certificate stores the

user’s certificates, containing the public key necessary

to protect the information he gathers.

ObservationalResearchSocialNetwork-InteractionandSecurity

61

String username

String email

String passwordHash

String name

int experienceLevel

User

String group

String username

Group

byte[] certificate

boolean invalid

Date invalidDate

Certificate

*

1

*

1

Figure 6: User elated entities.

5 SECURITY ISSUES

The ethical behavior inherent to all observation pro-

cedures demand rigorous security measures. In par-

ticular:

• Users must be authenticated;

• Data must be kept private;

• Users must be authorized to perform an action.

Each of this points depend on different mech-

anisms. Authentication is performed through the

identification of a user and verification. Privacy is

ensured through cryptography, both symmetric, to

cypher data, and asymmetric, to deal with the key

distribution. Finally, authorization depends on access

control, through an Access Control List.

5.1 Authentication

Before any user is allowed to perform any action, he

has to be authenticated or, in other words, his identity

has to be confirmed. This is performed in three pos-

sible ways: using something the user has, something

he knows or something he is or does. We chose to

authenticate the user through something he knows – a

password.

To make password cracking more difficult, we

add a salt to each password (Wagner and Goldberg,

2000). The salt is a sequence of characters, generated

through a Cryptographically Secure Pseudo-Random

Number Generator (CSPRNG), that causes the hash

to be different even is situations where the password

is the same. The salt is stored in the user table along-

side the hash (Figure 6).

The procedure to store a password requires that a

random salt is generated, using a CSPRGN. Next, the

salt is concatenated to the password characters and

the hash is computed, using the SHA256 algorithm.

Finally, both the salt and the resulting hash are stored

in the database.

When accessing the social network, the user is re-

quested a password. Since only the hash is stored in

the database, password validation require:

1. Retriving the user’s salt and hash from the

database;

2. Prepending the given password with the salt;

3. Computing the SHA256 hash;

4. Comparing the resulting hash with the one from

the database.

If both hashes match, the user is authenticated.

Otherwise, the password is incorrect. To ensure pri-

vacy, users also store their certificates in the system,

making the public keys available to other users and to

the system.

5.2 Privacy

Data has to remain confidential, regardless of where

and how it is stored. The nature of the TeObs So-

cial Network requires the existence of a rigid privacy

policy as well as a verifiable consent from a parent to-

wards the protection of children’s privacy and safety

online. In this situation, privacy is achieved through

cryptography.

All the observation material is cyphered before

storing, so that it remains protected against disclosure.

However, data should not be prevented to be shared

between authorized members, although it should be

completely protected to a third party.

Traditional cryptography falls under symmetric,

where the same key is used to cipher and to decipher,

and asymmetric, also knows as public key cryptogra-

phy. This uses two keys: a private and a public. One

of the keys is used to cipher and the other to decipher.

In TeObs we use symmetric cryptography to cipher

data and asymmetric to distribute the shared key (Fig-

ure 7).

When starting a project, the supervisor (the gray

circle with a ‘C’) creates a new Community. The pro-

cess starts by generating a key, which will be ciphered

to the supervisor’s public key (black key from the

Certificates repository), and stored in the KeyStore.

Only the supervisor (or another element through del-

egation) has the possibility to add members to the

community, automatically creating a relationship with

him.

When a new observer is added to the community,

the shared key is deciphered (using the supervisor pri-

vate key), ciphered to the public key of the new ob-

server and stored in the KeyStore. Prior to data gath-

ering, the observer retrieves and deciphers the shared

key from the KeyStore. All the data is then ciphered

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

62

Data access

Data generation

Key Generation

KeyStore

A

B C

Community

User A

Activity

Activity

Activity

User B

Activity

Activity

User C

Activity

Activity

Activity

Activity

A

C

B

Certificates

A

C

B

C

C C

B

B

B

A

A

A

Figure 7: Key management.

and stored in the Community, ensuring that only the

members have access to the content.

In other words, each community will have a sin-

gle, specific, shared key. Although simple, this re-

duces the risk of compromise the keys, since no key

exist before the start of the procedure and it changes

with the community. At the same time, the data is se-

cure from eavesdropping, even if all the database and

all the stores are attacked.

To protect data against unauthorized or improper

modifications, each community member digitally

signs the piece of information submitted to the Com-

munity with his private key. This allows confirming

the ownership as well as the integrity of the data.

5.3 Authorization

Cryptography protects privacy and integrity of infor-

mation, as described above. However, enforcing pro-

tection also requires that every access to a system and

its resources be controlled and that all and only autho-

rized accesses can take place (Samarati and de Vimer-

cati, 2001).

Access control models are generally concerned

with whether subjects (any entity that can manipu-

late information), can access objects (entities through

which information flows through the actions of a sub-

ject), and how this access can occur.

In the TeObs Social Network, the concept of Com-

munity defines the members with privileged access to

information. However, further, fine grained, access

control policies are necessary. Considering the pre-

vious social interactions, we have several access pro-

files (Table 2).

Table 2: Access profiles.

N No access

R Can read

W Can write

R/W Can read and write

D Can delegate access

Considering a community member as the subject

and the data as the object, the possibilities of access

include reading, writing or delegating control, as sum-

marized above. The relation between the subject, the

object and the associated actions define the access

control policies, which will have to be met by the se-

curity mechanism.

This approach is designated by Discretionary Ac-

cess Control (DAC), based on the identity of the re-

quester and on access rules stating what requesters

are (or are not) allowed to do. This is instantiated

in an Access Control Matrix, a three dimensions ma-

trix relating subjects, objects and actions (Lampson,

1974). However, since this matrix is very sparse, it is

not very efficient to be stored directly. An alternative

implementation allows storing the matrix by column,

defining Access Control Lists (ACL).

ACL are associated with the objects, registering

who has access to it and how. In TeObs this is stored

as an entity associated with the Activity and the

User, in a many-to-many association (Figure 5). The

ACL will have an entry for each user with access as

well as the authorized action (Table 3).

Table 3: Access Control List.

Activity 1

User A R

User B R/W

User C R/W/D

The ACL builds on top of the privacy mechanism

to further define the security policy. This allows re-

stricting the possibilities within the community, al-

lowing or denying specific members specific actions.

For example, an user may read, write or delete infor-

mation although another may only read it.

Each user is responsible for defining each activ-

ity’s ACL. However, he can also delegate this function

to other user, allowing the supervisor, for example, to

update it.

ObservationalResearchSocialNetwork-InteractionandSecurity

63

6 CONCLUSIONS

Quality in education depends on the teachers’ pro-

fessional development, enhanced by observational re-

search in preschool environment and sharing and

working in a community of practice. Traditionally,

this community is based on face-to-face discussion

and exchange of experiences. This learning organi-

zation can be instantiated in an online social network,

where communication is mediated by computers.

A web based community allows enhancing com-

munication processes between members, particularly

out of regular teaching periods. Moreover, it allows

the integration of professionally isolated teachers.

In this paper we propose an observational research

social network for preschool education, where the in-

teractions between members are maintained and ex-

tended with the possibility for asynchronous commu-

nication. Moreover, a database of previous knowl-

edge is also available, allowing better training and fur-

ther studies.

Ethical behavior is fundamental, particularly pri-

vacy and access control. Cryptography is used for ci-

phering information and for key distribution and dis-

cretionary access control is used to specify the infor-

mation each user can access and associated actions.

This social network is complemented with smart-

phone application for gathering and exporting data, as

well as web pages for overall process management.

REFERENCES

Bertram, T. and Pascal, C. (2004). Effective Early Learning

({EEL):} A handbook for evaluating, assuring and

improving quality in settings for Three to Five Year

Olds. Amber Publishing, Birmingham.

Bertram, T. and Pascal, C. (2006). The baby effective

early learning programme: Improving quality in early

childhood settings for children from birth to three

years. Birmingham: Centre for Research in Early

Childhood.

Bertram, T. and Pascal, C. (2009). Manual {DQP} - de-

senvolvendo a qualidade em parceria. Minist

´

erio da

Educac¸

˜

ao, Lisboa.

Boyd, D. M. and Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social Network

Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1):210–230.

Evans, K., Hodkinson, P., Rainbird, H., and Unwin, L.

(2006). Improving Workplace Learning (Improving

Learning). Routledge.

Garton, L., Haythornthwaite, C., and Wellman, B. (2006).

Studying Online Social Networks. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(1).

Laevers, F. (1994). Adult Style Observation Schedule for

Early Childhood Education ({ASOS-ECE)}. Centre

for Experiential Education, Lovaina.

Laevers, F., editor (2005). {Sics/Zicko.} Well-being and In-

volvement in Care Settings. A Process-oriented Self-

evaluation Instrument. Kind & Gezin e Research Cen-

tre for Experientel Education, Lovaina.

Lampson, B. W. (1974). Protection. ACM SIGOPS Operat-

ing Systems Review, 8(1):18–24.

Mesquita-Pires, C. (2012). Children and professionals

rights to participation: a case study. European Early

Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(4):565–

576.

Mesquita-Pires, C. and Lopes, R. (2014). Data Model

and Smartphone App in an Observational Research

Social Network. In 6th International Conference

on Computer Supported Education - CSEDU 2014,

Barcelona.

Samarati, P. and de Vimercati, S. (2001). Access control:

Policies, models, and mechanisms. Foundations of Se-

curity Analysis and Design, 2171:137–196.

Sheridan, S. M., Edwards, C. P., Marvin, C. A., and Knoche,

L. L. (2009). Professional Development in Early

Childhood Programs: Process Issues and Research

Needs. Early education and development, 20(3):377–

401.

Wagner, D. and Goldberg, I. (2000). Proofs of security for

the Unix password hashing algorithm. Advances in

CryptologyASIACRYPT 2000.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social

learning systems: the career of a concept. Social

learning systems and communities of practice.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

64