Procurement Auctions to Maximize Players’ Utility in Cloud Markets

Paolo Bonacquisto, Giuseppe Di Modica, Giuseppe Petralia and Orazio Tomarchio

Department of Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering, University of Catania, Catania, Italy

Keywords:

Cloud Market, Procurement Auction, Bidding Strategy, Cloud Simulations.

Abstract:

Cloud computing technology has definitely reached a high level of maturity. This is witnessed not just by

the interest of the academic community around it, but also by the wide adoption in commercial scenarios.

Today many big IT players are making huge profits from leasing their computing resources “on-demand”, i.e.,

letting customers ask for the amount of resources they need, and charging them a fixed price for each hour

of consumption. Recently, studies authored by economists have criticized the fixed-price applied to cloud

resources, claiming that a better pricing model can be devised which may increase profit for both the vendor

and the consumer. In this paper we investigate how to apply the mechanism of procurement auction to the

problem, faced by providers, of allocating unused resources. In particular, we focus on the strategies providers

may adopt in the context of procurement auctions to maximize the utilization of their data centers. We devised

a strategy, which dynamically adapts to changes in the auction context, and which providers may adequately

tune to accommodate their business needs. Further, overbooking of resources is also considered as an optional

strategy providers may decide to adopt to increase their revenue. Simulations conducted on a testbed showed

that the proposed approach is viable.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cloud computing aims to provide computing re-

sources to customers like public utilities such as

water and electricity (Buyya et al., 2008). In an

Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) cloud environment,

physical resources are packaged into distinct types

of virtual machines (VMs) and offered to customers.

A cloud customer, on the other hand, will purchase

VMs to run his applications, by looking for specific

resource requirements in terms of CPU, memory and

disk. Given the finite capacity for each type of re-

sources in each data center, a fundamental problem

faced by IaaS provider is how to select the price and

allocate resources for each type of VM services in or-

der to best match the interests of the customers while

maximizing his revenue. This issue is further com-

plicated by the fact that, differently from traditional

utility markets, cloud demand is strongly time vary-

ing and often burstly.

The resource allocation and trading mechanisms

used by the current cloud computing systems are in-

efficient and inflexible due to the flat rate pricing

model adopted. We argue that a fixed price-based re-

source allocation currently in use in cloud comput-

ing systems do not provide an efficient allocation of

resources and do not maximize the revenue of the

cloud providers. In a previous work (Di Modica

et al., 2013), we already showed that a better alter-

native would be to use auction-based resource allo-

cation mechanisms. In this paper we address issues

related to the bidding strategies adopted by providers

of computing resources in the context of procurement

auctions. We try to analyze all the factors that mainly

impact the strategic choices of providers in the acqui-

sition of the goods allocated through auctions. The

purpose of this work is not to devise an optimal bid-

ding strategy, but rather, to prove that any strategy

will have its objective guaranteed by the procurement

mechanism. We also devised a tentative provider’s

strategy which adapts its aggressiveness to the earlier

mentioned factors. In the addressed market scenario,

we stress that our attention is devoted to the optimiza-

tion of the utilization rate of providers’ data centers

and the utility of providers.

The remainder of the paper is structured as fol-

lows. Section 2 makes a review of the literature and

gives some rationale of the work. Section 3 intro-

duces the proposed idea and delves into technical de-

tails about procurement auctions. In Section 4 simu-

lation results are presented and discussed. Finally, the

work is concluded in Section 5.

38

Bonacquisto P., Di Modica G., Petralia G. and Tomarchio O..

Procurement Auctions to Maximize Players’ Utility in Cloud Markets.

DOI: 10.5220/0004854700380049

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science (CLOSER-2014), pages 38-49

ISBN: 978-989-758-019-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 RELATED WORK

All main commercial IaaS providers “comply” with

the On-Demand approach, and offer to charge cus-

tomers for the actual time frame during which the

resource is actually utilized

1

. They ask users pay

a fixed price for computing capacity by the hour.

The only chance for the customer to get discounts

on the price-per-hour is to opt on the reservation or

the flat rate charging models. According to these op-

tions, customers get a discount on the price but are

committed to longer periods of lease (from a month

to a year). Among commercial providers, the only

one that successfully proposed an approach alterna-

tive to the fixed-price is Amazon with its Spot In-

stance model

2

. This model enables the customer to

bid for what they call unused computing capacity.

Virtual machines are charged the Spot Price, which

is set by Amazon and fluctuates periodically depend-

ing on the supply/demand rate for computing capac-

ity. According to this model, on the one hand the

provider gives the customer the possibility to acquire

computing resources at a lower price then the stan-

dard; on the other one, whenever the resources’ de-

mand increases, the provider reserves the right to pre-

empt those resources and give them to better bidders.

This model represents the very first attempt to build

up a virtual market of computing resources regulated

by market prices, i.e., prices which dynamically fluc-

tuate according to offer and demand. In spite of this,

the model is still unclear (the formula of price fluc-

tuation is not known) and is not proved to be re-

sistant to potential malicious behaviors of customers

(dishonest customers can abuse the system and ob-

tain short-term advantages by bidding large maximum

price bid while being charged only at the lower spot

price (Wang et al., 2012)). Furthermore in (Agmon

Ben-Yehuda et al., 2011) authors prove that the Ama-

zon’s Spot Price is not market driven, rather is typi-

cally generated as a random value near to the hidden

reserve price within a tight price interval. The con-

sideration stemming from this observation is that a

provider, being an interested party, may not be a guar-

antee for the correctness of the price determination.

Instead, a third party broker should be in charge of

calling out prices in auction-based contexts. A quick

review of the recent literature proves that researchers

are very much concerned with the application of auc-

tion mechanisms to the problem of the allocation

(read “sale”) of computing resources. In (Risch et al.,

1

http://aws.amazon.com/ec2/

http://www.microsoft.com/windowsazure/

http://www.rackspace.com/

2

http://aws.amazon.com/ec2/spot-instances/

2009) authors propose a marketplace of computing

resources where prices are determined using an ex-

change market. In (Chard and Bubendorfer, ) authors

discuss several strategies that cloud providers should

adopt in order to reach high performance and to over-

come most of criticisms of auctions like high over-

heads and high latency using techniques like over-

booking and Flexible Advanced Reservations. They

propose several bidding functions but each one takes

into account only one parameter among those moni-

tored by a cloud provider. Our work is different as

we try to guarantee the provider’s utility maximiza-

tion through an adaptive strategy based on several pa-

rameters referring to the actual condition of resources

allocation, intentionally weighted by the provider in

order to address a specific target.

For the majority of researchers, combinatorial

auctions are the most appropriate sale mechanism for

allocating virtual machines in the cloud. In combi-

natorial auctions the participants bid for bundles of

items rather than individual items (Cramton et al.,

2005). This mechanism seems to perfectly fit the

Cloud context, as customers usually need to acquire

not just one resource but a bunch of resources (e.g.,

one for hosting the database server, one for the appli-

cation server and one for the web server). In (Wang

et al., 2012) authors propose a suite of computation-

ally efficient and truthful auction-style pricing mech-

anisms, which enable customers to fairly compete for

resources and cloud providers to increase their overall

revenue. (Zaman and Grosu, 2013) proposes a com-

binatorial auction-based protocol for resource alloca-

tion in grids. They considered a model where dif-

ferent grid providers can provide different types of

computing resources. Buyya et al. (Buyya et al.,

2010) propose an infrastructure for auction-based re-

source allocation across multiple cloud systems. In

(Vinu Prasad et al., 2012) authors address the sce-

nario of multiple resource procurement in the realm of

cloud computing. In the observed context, they pre-

process the user requests, analyze the auction and de-

clare a set of vendors bidding for the auction as win-

ners based on the Combinatorial Auction Branch on

Bids (CABOB) model.

The discussed works mainly focus on solving the

problem of optimal sale of resources in combinato-

rial auctions, which is known to be NP-hard. The

work we propose, instead of defining yet another sub-

optimal allocation algorithm, takes a different direc-

tion. From a strictly technical point of view, one of

IaaS providers’ main issue is to adopt an efficient allo-

cation scheme which allows them to map customers’

requests to virtual machines (or virtual resources, in

general) in an efficient way. Often, when a new re-

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

39

quest must be served there are many management op-

erations that need to be carried out along. Let us sup-

pose that an IaaS provider has a number of hosts, and

a new request R demanding some computing power

has arrived. According to both the actual hosts’ oc-

cupancy rate and the adopted allocation scheme many

different actions may be taken. For instance, comput-

ing capacity may be allocated in the host where the

computing availability best (or worst) fits the comput-

ing request. Or, computing capacity may be allocated

in an unloaded host running on a stand-by state. Or

again, a running virtual machine allocated in host H

1

may be migrated to host H

2

in order to make room

for R (whose size fits better in H

1

than in H

2

). Those

cited here are only a few of the many examples of

management issues that providers must face with.

The profit of a provider strongly depends on its

capability of keeping the hosts’ average occupancy

rate as high as possible. For their nature, comput-

ing resources can be regarded as perishable goods that

need to be sold within a certain time frame otherwise

they get wasted. Not selling a virtual machine in a

given slot time means a profit loss for the provider,

who anyway is spending money to keep the physi-

cal machines up and running. We then look at the

trade of computing resources from a new perspective,

in which providers, in the aim of maximizing their

data center’s occupancy rate, may be willing to attract

customers by lowering the offer price. On their turn,

customers may get what they need, at the time they

need it, at a price which is lower than the standard

price at which they usually buy. We advocate that

the market model best fitting this perspective is the

one which guarantees the sale of computing resources

through procurement auctions. Procurement auc-

tions (Klemperer, 1999) (also called reverse auctions)

reverse the roles of sellers and buyers, in the sense

that the bidders are those who have interest in selling

a good (the providers), and therefore the competition

for acquiring the right-to-sell the good is run among

providers.

The sale of computing resources through procure-

ment auctions will work as follows. The market gath-

ers computing demands from any customers. For each

computing request a procurement auction is publicly

called out. Providers can search the market in order

to identify the specific request(s) which best fits their

need in that particular moment (e.g., a request for a

virtual machine of a specific size that would “fill” a

given host’s capacity) and participate in the respec-

tive call(s). A call will be won by the provider offer-

ing to serve the demand at the lowest price. On the

provider’s side, this mechanism is profitable since the

huge number of computing demands gathered by the

market increases the chances of the provider to find

the one(s) satisfying their needs. In their turn, many

customers will be attracted by the possibility to get

what they ask at a price that is lower than the standard,

therefore will be stimulated to push their requests to

the procurement-based market.

3 PROCUREMENT AUCTION

MARKET

The purpose of this work is not to convince providers

to abandon the direct-sell mechanism in favor of the

procurement-based market. Providers have their reg-

ular customers, who issue requests which most of

the times have a well known timing. For this kind

of requests the most appropriate model is the direct-

sell/fixed-price, in that it provides guarantees for both

the provider and the customer. What we propose is

the adoption of an alternative, dynamic pricing model

for selling what is usually referred to as the unused

capacity, i.e., the residual capacity that, on average,

the provider is not able to sell through direct-sell.

Let us define the utilization rate U(t) as the frac-

tion of the overall unused capacity committed to serve

customers’ requests at time t . The lower U, the

higher the profit loss for the provider. In the aim

of maximizing the utilization rate (minimizing the

residual capacity) providers need to adopt new selling

strategies. The simplest strategy could just be lower-

ing the price per computing unit. Amazon currently

leases its unused capacity by adopting an auction-

inspired price strategy that let the customers acquire

resources for a price which is lower than the standard.

We argue that providers, to avoid “wasting” comput-

ing capacity, are willing to give up a portion of profit

per computing unit (same as it happens for sale of per-

ishable goods). As far as we know, the Amazon’s is

the only example of dynamic price strategy that is al-

ternative to the fixed-price. If on the one hand it is true

that customers benefit from low prices, on the other

one the proprietary mechanism by which the virtual

machines’ price fluctuates has never been disclosed.

The computing capacity’s actual supply/demand rate

is not shared to customers, nor the price policy has

ever been released.

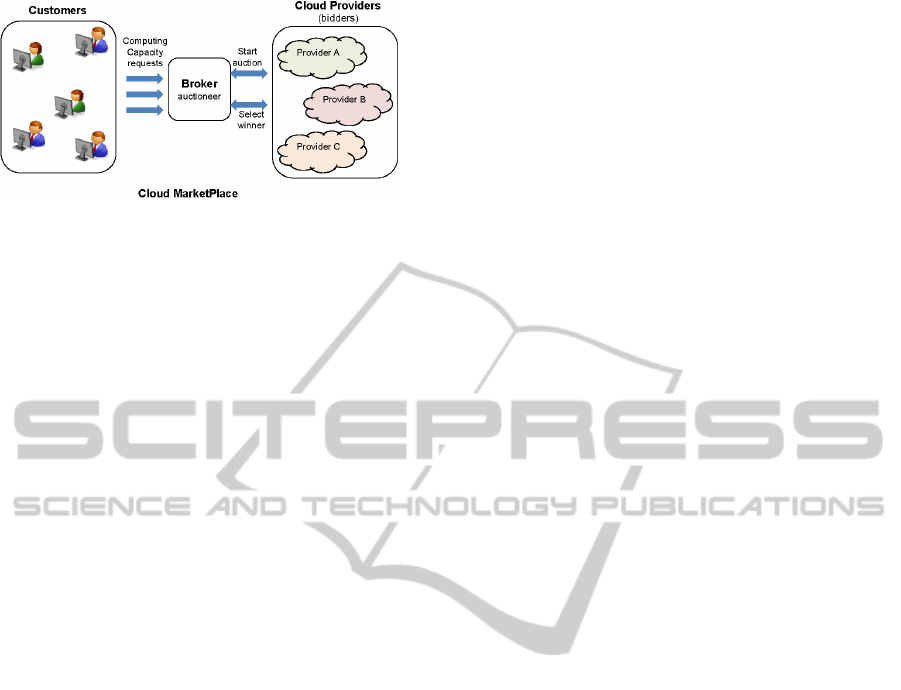

In this paper we propose the design of a market of

computing capacity (Figure 1), to which any provider

is admitted, and where computing resources can be

sold through auction-based allocation schemes. The

perspective is that of procurement auctions, where an

initial price is called out and bidders iteratively have

to call lower prices to win. The market mechanism

is the following. Customers communicate their com-

CLOSER2014-4thInternationalConferenceonCloudComputingandServicesScience

40

Figure 1: The Cloud Marketplace scenario.

puting demand to the market. A broker will take care

of demands. For each specific demand, the broker

(auctioneer) will run a public auction to which any

provider (bidder) can participate and compete for “ac-

quiring” the demand. The winning provider (who of-

fered the lowest price) will eventually have to serve

the demand. Being the auctions open to the participa-

tion of multiple providers, the competition is granted.

Providers will have to fight to gain the right-to-serve

the demand. Bidding strategies enforced by providers

can range from the most conservative to the most ag-

gressive. The determination of the final price is driven

only by the evaluation that each provider has on the

goods to acquire (i.e., the customer’s demand to be

served). Customers will get their demand served at

the lowest price. Further, they will have no more the

burden to search for providers, as providers are gath-

ered in the market. As for the broker, its income will

be evaluated in a way proportional to both the number

of transactions (auctions) it will be able to carry out

and the prices formed in the transactions.

3.1 Customer’s Demand

Customers need to acquire cloud resources to sat-

isfy their computing needs. Following the cloud

paradigm, the computing power of a physical ma-

chine can be adequately shaped to satisfy the most

demanding customer need, in terms of CPU cores,

CPU cycles, Mips and main memory size. In practice,

all cloud providers offer a restricted number of vir-

tual machines (VM) configurations (instance types),

which go from the very minimalist to the most pow-

erful one. In this paper we will refer to a classification

of VM instance types which recalls that of Amazon.

Though discrepancies exist between the classification

being presented and those adopted by other providers,

schemes that map the respective items can easily be

derived (but are out of the scope). In the rest of the

paper, we will then assume that customers’ demand

will address the following VM instance types:

• General Purpose.

– M1.small - 32/64-bit architecture, 1 vCPU,

1 ECU, 1.7GB RAM, 160GB Storage, Low

Bandwidth;

– M1.medium - 32/64-bit architecture, 1 vCPU,

2 ECU, 3.75GB RAM, 410GB Storage, Mod-

erate Bandwidth;

– M1.large - 64-bit architecture, 2 vCPU, 4 ECU,

7.5GB RAM, 820GB Storage, Moderate Band-

width;

– M1.xlarge - 64-bit architecture, 4 vCPU, 8

ECU, 15GB RAM, 1.6TB Storage, High Band-

width;

– M3.xlarge - 64-bit architecture, 4 vCPU, 13

ECU, 15GB RAM, 0 Storage, Moderate Band-

width;

• Compute Optimized.

– C1.medium - 32/64-bit architecture, 2 vCPU, 5

ECU, 1.7GB RAM, 350GB Storage, Moderate

Bandwidth;

– C1.xlarge - 64-bit architecture, 8 vCPU, 20

ECU, 7GB RAM, 1.6TB Storage, High Band-

width;

• Memory Optimized.

– M2.xlarge - 64-bit architecture, 2 vCPU, 6.5

ECU, 17.1GB RAM, 420GB Storage, Moder-

ate Bandwidth.

We also assume that customers may demand for

combinations of the above listed resources. For in-

stance, a customer may issue a request for three

M2.xlarge instances and four M1.large instances.

Along with the (combination of) resources needed,

the customer must communicate the time at which the

resource(s) need to be accessed (start-provision time)

and the time at which the resource provision must ter-

minate (stop-provision time).

3.2 Auction Types

Auctions are the tool that the broker will make use

of in order to allocate providers’ computing capacity

to customers’ demand. An auction can be run by the

broker as soon as a new demand has arrived. For a

given demand, the broker can choose from some auc-

tion types to run. The choice of the best suiting auc-

tion type is driven by several factors, which are object

of observation in this paper. Also, it is up to the broker

the setting of the initial price of the auction.

As outlined before, the typology of auction that

best fits the depicted context is the procurement auc-

tion. In a procurement auction the buyer (customer,

in our case) advertises a need (demand for computing

capacity) and sellers (providers) compete to provide

the service (virtual machines to satisfy the demand).

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

41

This leads to decreasing prices being offered during

the period of the procurement auction.

In this paper we will focus on three different types

of procurement auctions. The common part of the

three auction mechanisms is the auction preparation,

which provides that upon the arrival of a demand, the

broker issues a public “call for proposal” (CFP) to

invite providers. The CFP shall specify a minimum

set of auction parameters including the start-provision

time, the stop-provision time, the initial price (from

which discount bids are expected), the bidding rules

(who can bid and when, restrictions on bids) and the

clearing policy (when to “terminate” the auction, who

gets what, at what price). After having collected the

willingness of providers to participate in the auction,

the preparation phase ends up and the bargain starts

according to what is specified in the bidding rules

and the clearing policy. What characterizes one auc-

tion mechanism from another one is the information

specified in the bidding rules and the clearing policy.

For our purpose we will address the following mech-

anisms:

• English Reverse (ER)(Parsons et al., 2011). The

ER is a multi-round auction. The CFP specifies

the initial price from which discounting bids (of-

fers) are expected. The participating bidders can

post their offers. Discounting offers are called out,

so that every bidders is always aware of the refer-

ence price for which further discounts are to be

proposed. If no offer arrives within a time-frame

(publicly set in the CFP), the good will be as-

signed to the last best (i.e., the lowest priced) of-

fer. This type of auction allows bidders gather in-

formation of each other’s evaluation of the good.

• First Price Sealed Bid (FPSB)(Parsons et al.,

2011). The FPSB is a single-round auction, i.e.,

all bidders have the chance to bid just once, before

the auction being cleared. When bidders receive

the CFP, they check the initial price and decide to

either bid or not to bid. After all participants have

posted their bid, the broker clears the auction and

allocates the “demand” to the bidder who has val-

ued it the most (in the case of a reverse auction,

the least). The peculiarity of this auction is that

bidders are not aware of each other’s offer, as only

the winning bid will be broadcast at the end of the

auction.

• Second Price Sealed Bid (SPSB). Like the FPSB,

it is a single round auction. But with the differ-

ence that the one who wins the auction (i.e., who

offers the highest price) will pay the second high-

est bid price. This mechanism, applied to a re-

verse auction, aims at improving the provider’s

utility (refer to the next section for the definition

of the provider’s utility). In fact, according to

this mechanism each provider may keep its good’s

evaluation secret, and if they will win the good

they will be acknowledged a price which is higher

than their own bid, thus increasing the overall util-

ity.

3.3 Provider’s Strategy

One of the objective of this work is the study of an

adaptive (i.e., dynamic) strategy for the providers that

participate in procurement auctions. By strategy we

mean a set of rules producing the decisions a provider

must take to maximize their own business objective.

Basically, a strategy shall drive the provider in choos-

ing the right actions to be undertaken when competing

for the acquisition of a good (e.g., whether to partici-

pate in a given auction, to bid in a given round, not to

bid, which price to offer). In the strategy design, the

first step was to outline the main factors that may im-

pact such choices. Secondly, we tried to devise a dy-

namic strategy which accounts for the just mentioned

factors and smoothly adapt their fluctuations. Finally,

we set up and configured a test environment to ana-

lyze the results produced by the strategy.

According to the literature, the behavior of an auc-

tion’s participant is mainly driven by the information

the participant has on the value of the good being

sold (Klemperer, 1999). In respect to this informa-

tion, two basic auction models are possible: 1) the

private-value model, where each bidder has an esti-

mate of the good for sale, and that estimate is private

and unaffected by others’ estimates, and 2) the pure

common-value model, where the actual value of the

object is the same for everyone, but bidders have dif-

ferent private information on how much that value ac-

tually is. Combined models can also be derived from

the cited ones.

If we better analyze the context of cloud auctions,

a computing resource can be seen as a good whose ac-

tual value (price) is common to all providers. In fact,

though for computing resources we can not yet speak

of conventional “market prices”, all providers in their

regular sales adopt well known, leveled prices. We

can then conclude the actual values of such kind re-

sources are somewhat common to providers. In the

context of a procurement auction of computing re-

sources, the estimate E

pi

of the i-th provider for a

given good may differ from the the estimate E

p j

of

the j-th provider according to the diverse needs each

provider may have in pursuing their own business ob-

jective.

Primary objective of a provider is to maximize

what is referred to as Utility. Given a resource to

CLOSER2014-4thInternationalConferenceonCloudComputingandServicesScience

42

be allocated through an auction sale, the provider’s

Utility for that request is defined as the difference be-

tween the winning bid price and the evaluation that

the provider gives to the resource. (Wang et al., 2012).

Of course, the provider aims at maximizing the aver-

age utility for the resources they compete for. Recall-

ing the considerations made earlier, in the context of

an auction sale of spare resources this objective can

be pursued: a) by keeping the data center’s utiliza-

tion as high as possible; b) by bidding prices higher

than the personal evaluation (which we will refer to as

lower bound) and c) by choosing the most profitable

combination of customers’ request to serve.

We identified a non-exaustive list of factors which

may strongly influence the strategy of a provider in a

procurement auction.

• The duration of the customer task (demand) to be

served (L). The longer the task, the higher the

profitability for the provider, since the required

capacity will be committed for a longer time. A

provider, then, might prefer to participate in auc-

tions where long tasks are traded.

• The type of VM instance required to serve the cus-

tomer task (T ). Of course, the profitability of a

task is directly proportional to the task’s require-

ments in terms of amount of computing capacity

per hour, so providers may be motivated in point-

ing on auctions calling for a higher capacity/hour.

But depending on the actual utilization level of

both each single host and the whole data center,

it might not be possible to serve further tasks re-

quiring high capacity VMs.

• The gap between the potential revenue obtain-

able from serving the task the standard way (i.e.,

through the fixed-price market) and that obtain-

able by serving the task at the price called by the

auctioneer (G

r

). The revenue for serving a task is

given by the L times the price (P) of the resource

that will serve the task. This factor strongly de-

pends on the provider’s enforced revenue policy.

A provider pointing on auctions to sell their un-

used capacity might accept a much lower revenue

(bidding a lower price) in the case that expenses

are already covered. Conversely, the provider

might not be willing to excessively lower the price

in the case that expenses are not yet covered.

• The utilization of the particular physical machine

that is going to serve the customer’s request. The

marginal revenue, in fact, is affected by the uti-

lization level of a host: if a host is already running

and serving other tasks, adding more tasks to that

host “costs” less than activating a new host.

Finally, some considerations need to be made

about the lower bound. Each strategy must envision

an “exit condition”, which represents the condition

that, when verified, forces the exit of the provider

from the auction. When the provider decides to par-

ticipate in an auction, they will have to set the lower

bound price, which represents the maximum discount

that the provider is willing to offer for the good be-

ing traded in that auction. Of course, this parame-

ter only makes sense in multi-rounds auctions, as in

single round auctions actually exit is imposed by the

mechanism itself at the end of the first round. The

lower bound parameter actually represents the eval-

uation of the provider for a given good (customer’s

request). It incorporates all provider’s consideration

regarding the costs for executing a VM, managing a

VM’s life cycle and supporting the customer.

The objective of a strategy is to suggest the

provider the price to call for the next bid. In calling

a price, a strategy may be more or less “aggressive”,

i.e., may propose higher or lower discounts. We dis-

cuss two different strategies. One is driven by ran-

domness (aggressiveness is randomly chosen auction

by auction, round by round). The other is adaptive,

in the sense that is able to adapt the aggressiveness

according to the above listed factors. For this kind

of strategy, the aggressiveness can be tuned by ade-

quately weighting the factors.

Recalling a formula presented in (McAfee, 1987),

the adaptive strategy will suggest the next bid as:

bid =

n − 1

n − (1 − α)

∗ lastWinningBid (1)

where n is the number of bidders participating in

the auction and lastWinningBid is the price of the bid

that won the last round. In case of single-round auc-

tions and in the case of first rounds of multi-round

auctions, lastWinningBid will be the auction’s start-

ing price. The parameter α is calculated as follows:

α = w

1

∗U (t) + w

2

∗

L

L

max

+ w

3

∗

P

a

P

f

+ w

4

∗

T

vm

T

max

+ w

5

∗ H(t) (2)

As we can see in the equation 2, α depends on:

• U(t), the current utilization rate of the pool of

spare resources; the less U (t), the higher α, so

the evaluated bid price will decrease (in a reverse

auction, lowering the bid price means pointing to

gain the good). As expected, the aggressiveness

of a strategy increases with the reduction of the

utilization rate.

•

L

L

max

, the ratio between the time period for which

the computing resource is requested and the max-

imum time period for which a resource can be

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

43

requested

3

. The ratio will increase for requests

with longer execution time. The provider will

be more aggressive in auctions where longer cus-

tomer tasks are negotiated, as those ensure a

higher utilization of the data center and, as a con-

sequence, higher revenues.

•

P

a

P

f

the ratio between the resource’s starting price

in the auction and the corresponding price in the

standard fixed-price market. The provider’s ag-

gressiveness will be higher when the price at the

start of a round is closer to the reference price

(price at which resources are traded in regular

markets, or, direct-sell price). The more the round

price decreases, the lesser the provider’s aggres-

siveness.

•

T

vm

T

max

the ratio between the computing power of the

resource being traded in the auction and the com-

puting power of the highest resource. This fac-

tor increases the provider’s aggressiveness in the

case of customer tasks demanding high comput-

ing power. The higher the requested computing

power, the higher the task’s initial price. Further,

a highly demanding task requires a bigger capac-

ity on the data center, thus increasing the overall

utilization rate.

• H(t), the current utilization of the host on which

the customer task to serve will be scheduled. This

factor increases the α parameter and, therefore,

increases the provider’s aggressiveness. Recall-

ing a previous consideration, the provider is more

conservative in their strategy if for serving a task

a new physical machine has to be activated.

Each parameter is weighted by a factor

(w

1

,w

2

,w

3

,w

4

,w

5

), for which the following con-

straint applies:

5

∑

i=1

w

i

= 1 (3)

Different combinations of weights lead to differ-

ent strategies. Finally, in the adaptive strategy the

lower bound price will depend on α according to the

following equation:

Lb = P

f

∗ (1 − discount) (4)

where discount is

discount = (0.5 ∗ α) ± rand ∗ 0.03 (5)

and P

f

is the price of the resource advertised in the

standard fixed-price market. The maximum discount

3

In real situations the time period for which a resource

can be requested has no bound; in our simulation we will

take into account tasks lasting no longer than 24 hours

on the fixed price is evaluated as the 50% of α; the

higher alpha, the lower the bound. A variability of

3% was also introduced to model a differentiation

among providers, which reflects their respective per-

sonal evaluations.

3.4 Resource Overbooking

The auction mechanism causes a waste of computing

resources at the provider’s end. A provider may par-

ticipate in many auctions (say m) at the same time.

For each auction, no matter they win or lose, the

provider will have to reserve a pool of resources to ac-

commodate the customer’s request for which they are

competing. The number of auctions every provider

will participate depends on the instant capacity of

their free computing resources. In general, provider

will win n auctions, being n <= m, thus, for the du-

ration of all m auctions there may be a waste of re-

sources proportional to the number of lost auctions

(m − n). To overcome this limitation, the provider

may decide to participate in more auctions and com-

pete for customers’requests which they are not poten-

tially able to meet. This mechanism, also known as

resource overbooking, contributes to decrease the re-

source waste on the one hand, but on the other may

bring to situations where the provider runs out of

computing resources and may not honor one or more

contracts signed at the time they won the auctions. In

this cases, the risk compensation principle is applied

(Phillips, 2005), and the provider will incur penalties

which are proportional to their actual bid.

In order to implement such mechanism in our mar-

ket, we let the provider count on an amount of vir-

tual computing capacity (namely, overbooking capac-

ity) which is set to 20% of their real capacity. The

provider is then able to participate in m + o auctions,

where o is proportional to the overbooking capacity.

This way the number of won auctions will increase,

and the provider’s utilization rate will get closer to

1. In the case the provider won more auctions than

those they are actually able to serve, a penalty is due.

When an auction appoints as winner a provider who

is not eventually able to honor a request, the second

best bidding provider is chosen. If, again, the latter is

not able to serve the request, the third best is chosen,

and so on. In this chain, all providers are subjected to

penalties. The penalty is a monetary cost calculated

as:

penalty

it

=

P

i

− bid

it

P

i

− winnerBid

i

∗ P

i

∗ duration

i

(6)

where penalty

it

is the penalty for the i-th CFP due

by provider t, P

i

is the auction’s starting price, bid

it

is

CLOSER2014-4thInternationalConferenceonCloudComputingandServicesScience

44

Figure 2: Auction preparation phase.

the bid called by provider t, winnerBid

i

is the winner’s

bid price and duration

i

is the time frame for which the

computing resource is required by the customer. This

law aims at penalizing the providers proportionally to

their risk attitude. The auction winner who is eventu-

ally unable to meet the request will pay a penalty of

P

i

∗ duration

i

. The following best bidders (2nd, 3rd,

ect..) who on their turn are not able to serve the re-

quest will pay a lower penalty as their bid is higher

than the winner’s. If all participating providers hap-

pen to fail the provision due to the overbooking, the

auction will be closed and a new auction will be called

up.

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

In order to prove the viability of our proposal a sim-

ulative approach was followed. A prototype was

implemented on the well-known Cloudsim simula-

tor (Calheiros et al., 2011). We developed a new

component (the Auctioneer) and modified the be-

havior of other existing components (Datacenter,

Broker and Cloudlet). Cloudlet is the component

of Cloudsim representing the task submitted by the

customer, while Datacenter is representative of the

provider that will compete for acquiring the task.

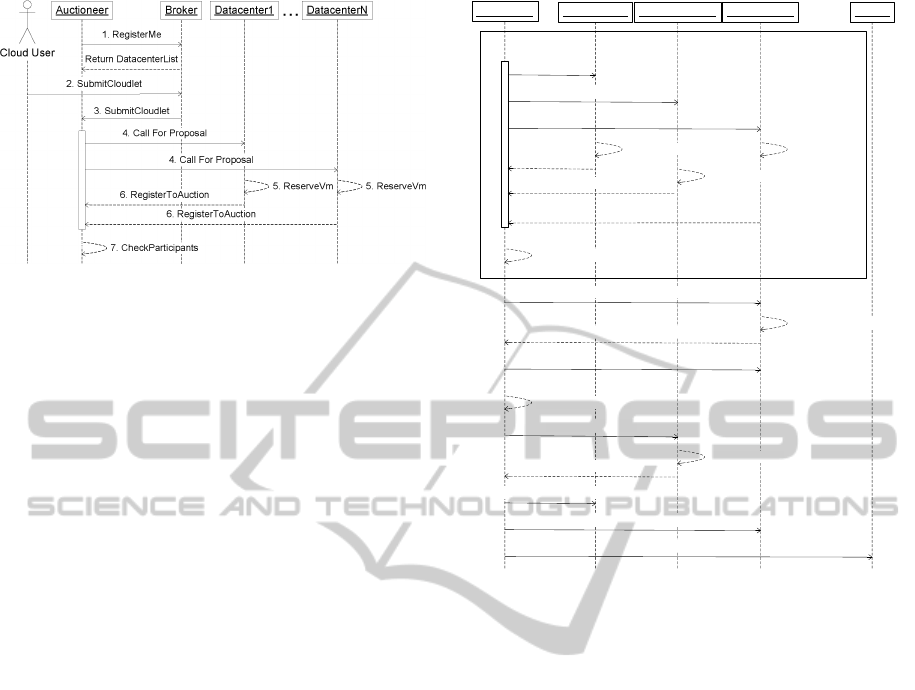

Figure 2 shows the basic steps of the auction

preparation phase. The Auctioneer registers to the

Broker (step 1) and receives the list of available Dat-

acenters. When a Cloudlet is submitted to the Broker

(step 2) it is passed on to the Auctioneer (step 3). The

Auctioneer broadcasts a Call For Proposals (CFP)

which specifies the task and the auction requirements

(step 4). Each interested Datacenter checks its own

capacity, reserves a VM and responds to the call (step

5-6). If the Datacenter has run out of physical re-

sources, but is adopting the overbooking mechanism,

it will check out whether the overbooking limit has

been overcome. If not, it will answer the call. If at

Auctioneer

Datacenter1

DatacenterN-1 DatacenterN

Broker

1.StartRound

1.StartRound

1.StartRound

2. CalculateBid

2. CalculateBid

2. CalculateBid

ReturnBid

ReturnBid

ReturnBid

3. SelectWinner

Loop until Max Nr Rounds or No Response

4. NotifyAuctionWin

5. UnableToInstantiate

return FailInstantiationOfVm

6. NotifyPenalty

7. SelectNextWinner

8. NotifyAuctionWin

9. InstantiateVm

Return Vm

10. CommunicateResult

10. CommunicateResult

11. CommunicateBinding

Figure 3: Auction running phase.

least two Datacenters answers the CFP (step 7), the

auction is ready to start.

The auction running phase is depicted in Figure 3.

The Auctioneer notifies the participant that the round

is open (step 1). At the beginning of each round the

starting price is communicated to the participants. In

the very first round the starting price is set equal to

a standard on-demand fixed-price. In the following

rounds the initial price is the price of the winning bid

of the previous round (this applies only to English

auctions). Each Datacenter calculates the bid accord-

ing to its strategy (step 2) and submits it to the Auc-

tioneer, who will appoint the winner (step 3). If the

auction type is multi-round, the bidding procedure is

repeated until the exit condition holds true. For in-

stance, if the auction is of English type it terminates

when no bid has been received within a round. When

the auction is closed, the Auctioneer sends the result

to the winner (step 4) and wait for the Ack. If the

winning Datacenter is not able to serve the request

(step5), it will return a negative Ack. The Auction-

eer will then contact the second best bidder. If again,

the latter has run out of resources, the process will go

further until a positive Ack is returned (step 10) or no

Datacenter is able to honor the contract. In the first

case the auctioneer notifies the losers (step 11) and

the broker that will bind the VM to the winning Dat-

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

45

Table 1: Weight Setting for the Datacenters’ strategies.

Datacenter ID Strategy w

1

w

2

w

3

w

4

w

5

DC1 Adaptive 0.6 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1

DC2 Adaptive 0.1 0.6 0.1 0.1 0.1

DC3 Adaptive 0.1 0.1 0.6 0.1 0.1

DC4 Adaptive 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.6 0.1

DC5 Adaptive 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.6

DC6 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC7 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC8 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC9 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC10 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC11 Random

acenter (step 12). In the second case the auction is

considered unresolved, and a new auction is called.

Typical Datacenters’ VM allocation policies are:

• First fit: a VM is allocated in the first available

host which is capable of running it. According to

this policy, a single physical machine is used to

host VMs until there is available computing ca-

pacity. When that machine capacity is saturated,

a new unused physical machine will be activated.

• Worst fit or Balanced allocation: a VM is allo-

cated in the less saturated host among those capa-

ble of running it. This policy ensures a balancing

of the load among the hosts, but causes high frag-

mentation of hosts’ computing capacity.

• Best fit: a VM is allocated on the host having the

least amount of unused capacity among those ca-

pable of running it. This policy optimize the re-

source utilization. This is the policy we used for

our tests.

To test the adaptive strategy, we created a set of

11 Datacenters, ten of which adopt the proposed adap-

tive strategy, while one adopts a Random strategy: the

latter makes its bids using the same equation of the

adaptive strategy (Eq. 1), where the α parameter is as-

signed random values in the [0,1] range, without any

specific objective to pursue. The weights characteriz-

ing the α parameter ((Eq. 2) are shown in Table 1. As

the reader may notice, strategies were expressly split

in unbalanced, for which Datacenters point on just

one factor, and balanced, for which all the weights

are assigned the same value.

The objective of the simulation is to show that

strategies actually guide Datacenters in the choice of

tasks to compete for. Every Datacenter counts 70

hosts, each characterized by the following features:

• number of cores uniformly chosen between

[64,128,256,512];

• RAM: 320 GB;

• Storage: 10 TB.

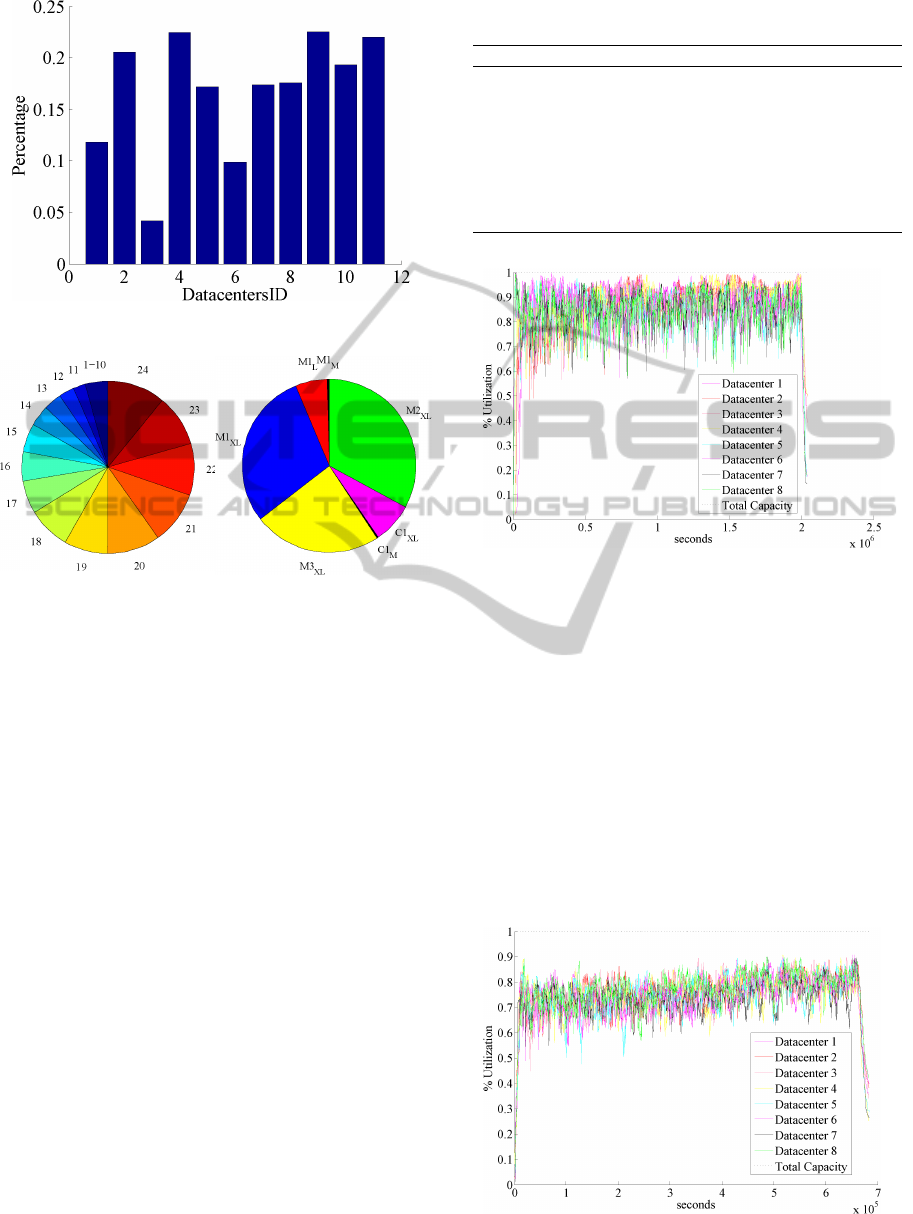

Figure 4: Datacenters Utilization: ER Auction.

A core is modeled in CloudSim with a capacity of

2400 Mips. in the first battery of simulation we sub-

mitted 25000 cloudlets having a length uniformly dis-

tributed in the range [1,24] hours and requiring a VM

type uniformly distributed in the range of the eight

VM types described in Section 3.1. The interarrival

times of the cloudlets are distributed accordingly to

a Poisson distribution, with λ = 0.1 (10 secs is the

maximum time that lapses between the arrivals of two

consecutive cloudlets). From early results, we noticed

that the adaptive strategy of each Datacenter guaran-

tees the achievement of the objective, regardless of

the specific auction type. For this reason (but also for

space reasons) we are going to show the results ob-

tained from testing the English Reverse Auction.

The main parameter we measured was the utiliza-

tion rate of the Datacenters, which is depicted in Fig-

ure 4. We can observe that all the Datacenters (DC)

pursuing one (or a combination) of these two objec-

tives 1) to acquire VMs that require high capacity in

terms of computing resources and 2) to obtain longer

lasting tasks, actually reach an high level of utilization

rate (in Table 1 DC2 and DC4 respectively).

DC11, that adopts the Random strategy, reaches

an high level of utilization rate too, because it can eas-

ily win auctions for tasks that do not meet the objec-

tives of other Datacenters (i.e. low performing VMs,

short tasks).

DC1’s objective is to optimize the utilization rate;

in the graph it can be noticed that after reaching an

utilization rate between 60% and 80%, it is not able

to further increase it, as its objective has almost been

reached: the strategy aggressiveness decreases in a

way that no more auctions are won.

The Datacenter that obtains the lowest utilization

rate (around 20%) is DC3; it exhibits low aggres-

siveness in the auctions as its objective is to obtain

cloudlet with a price not too far from a standard on-

demand fixed-price. However, as it can be seen in Fig-

ure 5 where the revenue loss percentage of the Data-

CLOSER2014-4thInternationalConferenceonCloudComputingandServicesScience

46

Figure 5: Revenue Loss Percentage per Datacenter.

(a)

(b)

Figure 6: Auctions won by DC2 and DC4, grouped by the

length of the Cloudlets the type of VMs respectively.

centers is shown, the objective of DC3 guarantees the

lowest revenue loss. Datacenters with balanced strat-

egy may also avoid revenue losses while, at the same

time, reaching a better utilization rate than DC3.

Finally, we report some graphs showing the

cloudlet characteristics of auctions won by two spe-

cific Datacenters. Figure 6(a) shows the rate of

auctions won by DC2, grouped by the length of

the cloudlets expressed in hours. DC2 mainly won

cloudlets with a length of more than eleven hours (the

reader can check in Table 1 that the weight of param-

eter related to the length of the cloudlets is the high-

est). Figure 6(b) depicts the auctions won by DC4. It

mainly wins auctions requiring high performing VMs,

as it strategy is set to point on that type of VMs.

In order to check the overbooking mechanism a

new simulation battery was run. We created a set of 8

Datacenters enforcing an adaptive strategy with bal-

anced weights, as shown in Table 2. First, the sim-

ulator was fed with 40.000 cloudlets having a length

uniformly distributed in the range [1,12] hours and

poissonian arrivals with λ = 0.01. In Figure 7 we may

notice that all datacenters reach an utilization very

close to 100%. This is due to the fact that cloudlets

are long (in terms of time required by the task) and

Table 2: Weight Setting for the Datacenters’ strategies.

Datacenter ID Strategy w

1

w

2

w

3

w

4

w

5

DC1 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC2 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC3 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC4 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC5 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC6 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC7 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

DC8 Adaptive 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

Figure 7: Datacenters Utilization without overbooking -

40000 Cloudlets, max length = 12h, λ = 0.01.

distant enough (100 secs is the cloudlets’ interarrival

time). We then repeated the simulation with the same

number of cloudlets but with a length uniformly dis-

tributed in [1,6] and poissonian arrivals with λ = 0.06

(17 seconds between consecutive cloudlets). In this

case the average utilization decreases to 70-80%, as

shown in Figure 8.

What happens is that, being the interarrival time

shorter, datacenters simultaneously engage in many

auctions. Each datacenter will only win a subset of

these auctions, which are also very short, thus it will

not be able to saturate its capacity. In this specific case

Figure 8: Datacenters Utilization without overbooking -

40000 Cloudlets, max length = 6h, λ = 0.06.

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

47

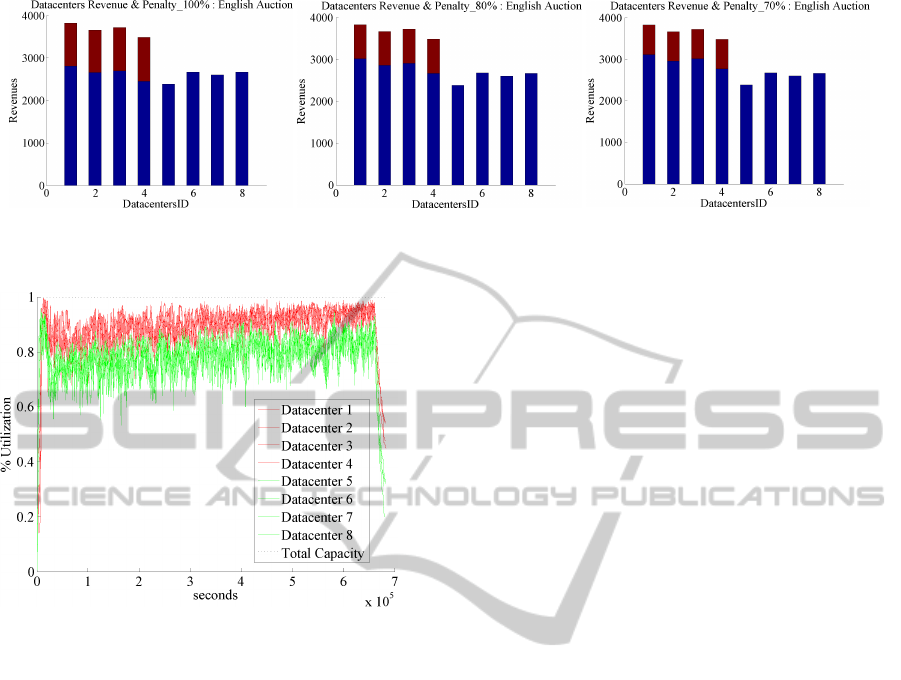

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 10: Overbooking Revenues and Penalties.

Figure 9: Datacenters Utilization with overbooking - 40000

Cloudlets, max length = 6h, λ = 0.06.

it may be of help to opt on the overbooking. We then

ran a new simulation, with the same parameters, but

configuring four of the eight datacenters to enforce a

20% of overbooking (DC1,DC2,DC3,DC4). Figure 9

shows that the the overbooking datacenters (depicted

in red) reach a very high utilization (close to 100%).

The collateral effect is of course that they incur penal-

ties, which have been evaluated with the formula in 6.

The revenue of datacenters enforcing the overbooking

drops below the revenue of datacenters which do not

use overbooking, as depicted in 10(a). Put in this way,

there is no point in opting for the overbooking. We

considered new formulas for the evaluation of penal-

ties which consider a reduction of 20% and 30% with

respect to the penalty evaluated in 6. Figures 10(b)

and 10(c) shows that with the new formulas data-

centers enforcing the overbooking have an acceptable

revenue. This is to say that overbooking is an opportu-

nity which must be carefully evaluated by datacenters,

and must be suitably tuned against the penalty policy

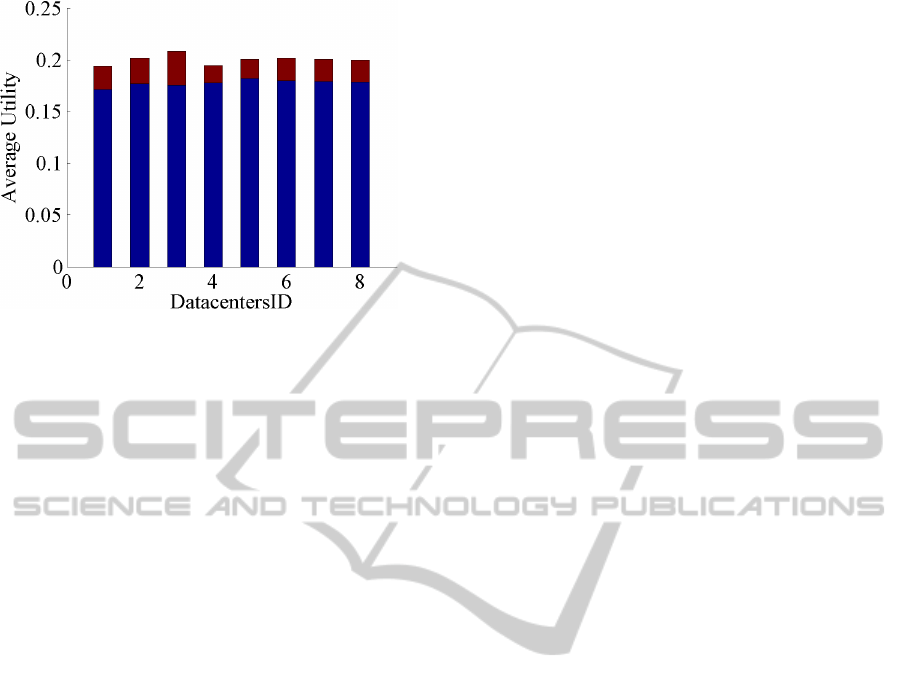

adopted by the market. Last consideration is on single

round auctions. Both First and Second Price Sealed

Bid did not provide encouraging results for the over-

booking. This is because the auctions are resolved in

a very short time and the utilization of resources is

not as dynamic as it is in a multi-round auction. We

have then compared the performance of the First and

the Second Price Sealed Bid auctions focusing on the

average utility of the provider. As depicted in Figure

11, the second price auction guarantees, on average,

a better utility. This kind of auction, in fact, let the

datacenter bid its real evaluation of the cloudlet pre-

venting the utility from excessively decreasing.

5 CONCLUSION

Cloud computing has stimulated a great interest both

in the academic community and in business contexts.

More and more IT players look at this technology as

a great opportunity of increasing their profit. Though

several studies report the cloud services’ market rev-

enue is rocketing, economists say the business po-

tential of cloud computing is not yet fully exploited.

There is not yet an open market of cloud resources

where providers and consumers can meet to satisfy

their needs. In this paper we propose a market of

resources where demand and offer of resources can

be matched in auction-based sales. Specifically, we

looked at this market from the perspective of the

provider, who needs a strategy to allocate at best their

unused computing capacity. We proposed an adaptive

strategy that, suitably tailored to the provider’s busi-

ness objective, will help them to maximize the rev-

enue in the context of procurement auctions. Also,

the resource overbooking mechanism has been inves-

tigated as an optional strategy providers may adopt

in order to increase their revenue. Simulations run to

test the proposed approach gave encouraging results,

by showing that each provider is able to reach their

objectives by finely tuning the weights associated to

their strategy. In the future, more factors will be taken

into account in the definition of the provider’s strat-

egy. Further, the business models of the broker of re-

sources (auctioneer) will also be investigated, in order

to prove that a market model based on procurement

CLOSER2014-4thInternationalConferenceonCloudComputingandServicesScience

48

Figure 11: Utility Comparison between FPSB and SPSB.

auctions can yield profit for all market actors.

REFERENCES

Agmon Ben-Yehuda, O., Ben-Yehuda, M., Schuster, A.,

and Tsafrir, D. (2011). Deconstructing amazon ec2

spot instance pricing. In Cloud Computing Technol-

ogy and Science (CloudCom), 2011 IEEE Third Inter-

national Conference on, pages 304–311.

Buyya, R., Ranjan, R., and Calheiros, R. N. (2010). Inter-

cloud: utility-oriented federation of cloud computing

environments for scaling of application services. In

Proceedings of the 10th international conference on

Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing

- Volume Part I, ICA3PP’10, pages 13–31.

Buyya, R., Yeo, C. S., and Venugopal, S. (2008). Market-

oriented cloud computing: Vision, hype, and reality

for delivering it services as computing utilities. In

High Performance Computing and Communications,

2008. HPCC ’08. 10th IEEE International Conference

on, pages 5 –13.

Calheiros, R., Ranjan, R., Beloglazov, A., De Rose, C. A. F.,

and Buyya, R. (2011). Cloudsim: A toolkit for model-

ing and simulation of cloud computing environments

and evaluation of resource provisioning algorithms. In

Software: Practice and Experience.

Chard, K. and Bubendorfer, K. High performance resource

allocation strategies for computational economies. In

IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Sys-

tems, volume VOL. 24, NO. 1.

Cramton, P., Shoham, Y., and Steinberg, R. (2005). Combi-

natorial auctions. The MIT Press.

Di Modica, G., Petralia, G., and Tomarchio, O. (2013). Pro-

curement auctions to trade computing capacity in the

Cloud. In Eighth International Conference on P2P,

Parallel, Grid, Cloud and Internet Computing (3PG-

CIC 2013), Compiegne (France).

Klemperer, P. (1999). Auction theory: A guide to the liter-

ature. Journal Of Economic Surveys, 13(3).

McAfee, R. P. e McMillan, J. (1987). Auctions and bidding.

Journal of Economic Literature, 15:699–738.

Parsons, S., Rodriguez-Aguilar, J. A., and Klein, M. (2011).

Auctions and bidding: A guide for computer scien-

tists. ACM Computing Surveys, 43(2).

Phillips, R. (2005). Pricing and revenue optimization. Stan-

ford University Press.

Risch, M., Altmann, J., Guo, L., Fleming, A., and Courcou-

betis, C. (2009). The gridecon platform: A business

scenario testbed for commercial cloud services. In

Grid Economics and Business Models, volume 5745,

pages 46–59. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Vinu Prasad, G., Rao, S., and Prasad, A. (2012). A combi-

natorial auction mechanism for multiple resource pro-

curement in cloud computing. In Intelligent Systems

Design and Applications (ISDA), 2012 12th Interna-

tional Conference on, pages 337–344.

Wang, Q., Ren, K., and Meng, X. (2012). When cloud

meets ebay: Towards effective pricing for cloud com-

puting. In INFOCOM, 2012 Proceedings IEEE, pages

936–944.

Zaman, S. and Grosu, D. (2013). Combinatorial auction-

based allocation of virtual machine instances in

clouds. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput., 73(4):495–508.

ProcurementAuctionstoMaximizePlayers'UtilityinCloudMarkets

49