The Experiment Has Shown

Set Your Own Goal and save Electricity!

Jurek Pyrko and Magdalena Uggmark

Department of Energy Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Keywords: Electricity Saving, Energy Feedback, Energy Visualization, Smart Energy Use.

Abstract: This study describes the final results from so-called “The Experiment - Swedish largest energy saving

experiment” carried out by E.ON Sweden. The purpose of the Experiment was to investigate whether

visualization of electricity consumption in real time would lead to a reduced electricity use. Almost 10,000

customers participated in the project and received displays where they could observe their electricity use.

Over 50% of the participants made an actual electricity saving; for these customers the mean electricity

saving became 8%. At the beginning of the Experiment, participants could set a saving goal and about 22%

of the customers managed to achieve the target. This group saved about 15% of electricity. All the

participants in total had made a saving of 0.7% compared to a control group that had increased their use by

1.5% during the same period. The impact of different factors on the final result was investigated in four

segmentations after space heating type, family composition, level of education and bidding area. Four

surveys were sent out to all participants to investigate their opinions and views on the Experiment. The

interest for possible changes in the service and the willingness to pay for it was also investigated.

1 INTRODUCTION

Power company E.ON Sweden launched, as they

called, “The Experiment - Swedish largest energy

saving experiment” where 10,000 customers partici-

pated and tried on energy feedback technique called

100Koll. The main question of this experiment was

weather the involved households could save

electricity by getting their usage visualized and by

setting up clear saving goals, which was a new way

that has never before been tested in an experiment

on the same scale. Furthermore, this experiment

covered a full year, which is also rare for this type of

investigations.

The Experiment started on February 1st, 2012

and lasted a whole year until January 31st, 2013.

10,000 grid customers of E.ON used home displays

retrieving data from smart meters, giving possibility

to follow household electricity consumption in real-

time. Participants of the Experiment could also log

into a website "My Account" and download a mobile

application to monitor their daily electricity

consumption.

A control group of 2,000 households was

randomly chosen by the energy company among all

the customers in the country (besides bidding area 1

in Northern Sweden - as for the experiment group),

not participating in the Experiment and not being

aware that they were included in the control group in

order to evaluate their energy consumption change

and compare it with the results from households

participating in the Experiment.

1.1 Motivation Events

In order to increase participants' motivation to

change their habits and achieve reduction of

electricity use, five so-called “motivation events”

were planned during the Experiment (E.ON, 2013).

The aim of these actions was to generate interest in

savings, in various ways, and to encourage partici-

pants to try to save even more electricity. Some of

them were connected to TV-commercials, billboards

and advertisements in newspapers all over the

country. The results of these campaigns were

evaluated in two surveys during the Experiment.

The first period started with the motivation case

called "Balance". The participants could download

an application to their smart phones to track the

electricity usage of the households visualized in

Swedish currency instead of kWh, see Figure 1.

179

Pyrko J. and Uggmark M..

The Experiment Has Shown - Set Your Own Goal and save Electricity!.

DOI: 10.5220/0004861401790184

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart Grids and Green IT Systems (SMARTGREENS-2014), pages 179-184

ISBN: 978-989-758-025-3

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Figure 1: Visualization of the Balance.

Second period was called "Neighbour Feud" and

was a game between neighbours. 5 families in the

neighbourhood could compete with each other to see

who was able to save the most of electricity during

the game, see Figure 2.

Figure 2: The “Neighbour Feud” on a smart phone display.

Then, the "Carrot" was a period during the

Experiment where the households could send in their

saving tips. The best of them were later rewarded

with prizes and some saving tips were illustrated in a

playful manner by cartoonist Henrik Lange (see

Figure 3) and in humoristic TV-advertisements.

Figure 3: Example of energy saving tips from the

motivation booster Carrot - The Anonymous Energy-

holics. (Text: Change your behaviour! “Hej! My name is

Gustav and I don’t turn the light off when I leave a

room.”)

After that, during the autumn 2012, the fourth

motivation case called “General” started. Through a

special app, downloaded from the Experiment’s

website, daily reminders were sent of things possible

to do and with inspiration and challenge to do even

more savings - much like a personal “energy coach”,

see Figure 4.

Finally came the "Bongo", a small creature who

appealed to the Experiment participants’ empathy

being very sad and feeling sick if the family

members did not save electricity, see Figure 5.

The boosting period that was most appreciated

by the participants was the "Balance". They felt that

it helped them the most with their electricity saving

efforts.

The overall interest was quite low for all the

motivation cases. During the interviews it was

revealed that some people felt that motivation cases

were a bit bizarre in an otherwise so important and

serious subject as energy saving. One participant

also pointed out the contradiction in messages in the

game "Neighbour Feud". The more the family saved,

the greater became the house and at last it could end

up with a helipad on the roof of this already very

spectacular building.

SMARTGREENS2014-3rdInternationalConferenceonSmartGridsandGreenITSystems

180

Figure 4: Motivation booster ”The General”. (Text on the

display says: “Not bad! I’ve checked your electricity use

and it’s sinking. Is there something more you can do to

lower it further? Think really carefully now!”).

Figure 5: “Bongo” on a smart phone display.

2 METHODS OF EVALUATION

The scientific evaluation of the whole Experiment

was carried out at the Department of Energy

Sciences at the Lund University and reported in

three publications (Andersson and Larsson, 2012),

(Taimor and Hols, 2013), (Uggmark, 2013).

Electricity consumption during one calendar year

(Feb 1, 2012 - Jan 31, 2013) was compared with

equivalent period 2011-2012. Monthly electricity

consumption data was collected and analysed for

each household showing how the electricity

consumption had changed compared to previous

year. For electrically heated households the data was

corrected for outdoor temperature variations.

A particular methodology was developed by the

authors to calculate electricity savings. The

percentage of electricity used for space heating was

calculated as a difference between electricity use

during winter (October -April) and summer (June-

August) months. Degree-days values were obtained

from the energy company and processed before they

were allotted to the households.

Four web-based surveys and an interview study

with limited amount of households were conducted

during the Experiment in order to examine how the

participants experienced different aspects of the

Experiment - from technology to engagement. The

content and structure of each survey was designed in

cooperation with representatives from the energy

company. The responses from the questionnaires and

the facts about participants of the Experiment were

put together to enable the segmentation of different

test groups. Statistical tests were then performed to

ensure that any differences between groups were

significant and not just a coincidence.

Some specific conditions for participation in the

Experiment were required:

1. the household should be a customer of E.ON;

2. the participants lived in single-family houses;

3. the electricity use was at least 10,000 kWh per

year (which usually means for Swedish

conditions that electricity is used both for space

heating and household needs).

4. the household should decide an electricity saving

target for the coming year (from 1 to 25%).

Totally, over 8.000 households participated actively

in the Experiment. Unfortunately, as the analyses

showed later, about 800 of them had electricity use

below 10,000 kWh per year.

Annual electricity consumption (between Febru-

ary 1, 2012 and January 31, 2013) was compared

with equivalent period year before (February 2011 -

January 2012).

Because of the weather-related changes in heat

demand, the evaluation of electricity savings from

one year to another has to consider how the outdoor

temperature differ between the two years. The space

heating data was corrected for outdoor temperature

TheExperimentHasShown-SetYourOwnGoalandsaveElectricity

181

variations for all electrically heated households

(direct resistive heating, electric furnaces or heat

pumps).

In this way, the electricity savings were defined

as temperature corrected difference between the year

of the Experiment and the year before.

The methodology used for temperature correc-

tion was developed by one of the authors and is

presented in detail in the final report (Uggmark,

2013).

The method used was based on degree-days for

each geographical location and on the assumption

that the electricity use during the summer months

(June to August) might represent the use of

electricity for household purposes and tap hot water

preparation. This electricity was assumed as constant

over the year. In this way the energy consumption

was only adjusted for the part of electricity used for

space heating.

Four web-based surveys were conducted during

the Experiment with responses according to a 6-

grade Likert´s scale. The content and structure of

each survey was designed in cooperation with the

staff from the energy company. The responses from

the questionnaires and the facts about households

were put together to enable the segmentation of

different experiment groups. Each question was

evaluated and the level of “belief” or “scepticism”

was calculated.

Statistical tests were then performed to ensure

that any differences between groups were significant

and not just a coincidence. Kruskal-Wallis test and

Chi2-test were used to examine the significance of

the response results (significance level 0.05).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Electricity Savings

The final result of the Experiment is based on 8,040

participating households. At the beginning of the

Experiment, the participants were asked to decide

the electricity saving target during the coming year.

Of these who actively participated, about 23%

achieved or exceeded their stated energy saving

targets. This group saved about 15% of electricity.

Of the remaining active households, about 34%

saved electricity but stayed below their saving

targets. About 43% of the households even raised

their consumption, in some cases as much as by

70%.

Somewhat over 50% of the households who

participated in the Experiment made some electricity

savings (>0) compared to the year before. Their

average savings were of 8%.

The group “Active households” comprises

households participating actively in the Experiment

by answering surveys (3985 households). This group

as a whole saved 1.68% of power. In this group,

totally 2,203 households saved 8.40% of the

electricity. Those who reached their targets within

this “active” group (886 households) saved 14.88%,

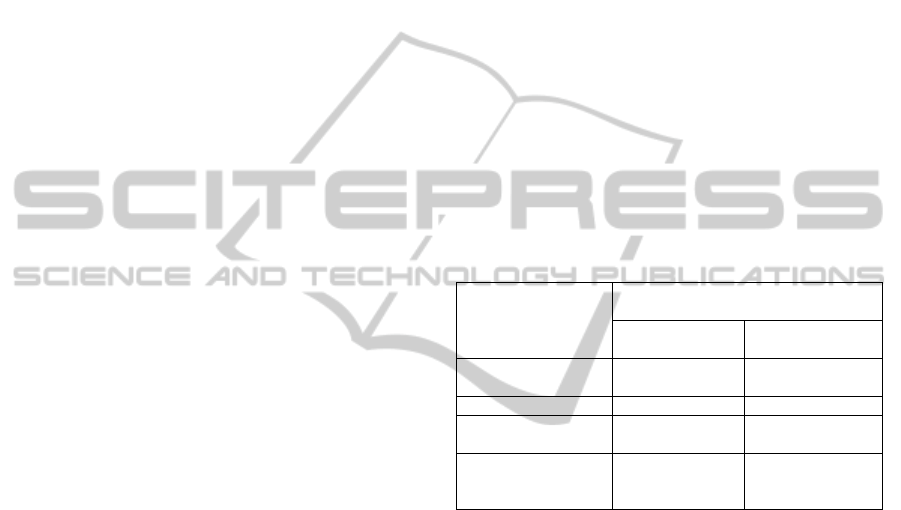

see Table 1.

The analysis made with the same criteria for the

Control group (2,000 households) showed that this

group, on average, increased its use of electricity by

1.50% during the same period.

The fairly similar result was identified for those

participants of the Experiment who did not put up

the saving targets (about 4,000 households) in the

beginning of the Experiment. This group had also

increased the electricity consumption by 0.2%.

Table 1: The final energy savings in the Experiment

(Uggmark, 2013).

Total electricity saving

(+values = saving)

Experiment

group

Control group

All households

0.74%

-1.50%

‘Active’ households

1.68%

-1.50%

‘Active hh’ who

’Saved power’

8.40% 8.33%

‘Active hh’ who

’Reached saving

target’

14.88%

NA

To investigate closer whether different groups

among the participants had better (or worse) electri-

city saving results compared to the others, four

segmentations after “space heating type”, “family

composition”, “level of education” and “bidding

area” (there are 4 such areas in Sweden) were made.

The most noticeable result from the segmen-

tations was that bidding area 4 (Malmö) in the south

of Sweden, usually having higher electricity prices,

had the highest saving of 2% and that bidding area 3

(Stockholm) made a significantly lower savings.

Households within bidding area 2 (Sundsvall)

actually increased their use of electricity with

approximately 0.6%.

3.2 The Participants' Experiences

To collect and evaluate participants' opinions on the

Experiment, four surveys and an interview study

was made. Surveys were sent out to all participants

to investigate their own opinions on for example the

SMARTGREENS2014-3rdInternationalConferenceonSmartGridsandGreenITSystems

182

motivation cases and to study their views on the

Experiment. The interest for possible changes was

also investigated to see what could make the service

more attractive and so was also the willingness to

pay for the service. The survey ended with a

question whether the respondents could consider

participating in an interview. 18 respondents were

later contacted for a short interview so that some

questions could be investigated further.

It appeared that many participants were very

positive about the Experiment. Most of the

households felt that they would benefit from the

equipment in the future and would be very

disappointed if the service disappeared.

In addition, slightly more than half of the

households were willing to pay for the service.

Families with children and those who had reached

their saving target were in slightly higher extent

willing to pay. Not surprisingly - those who reached

their electricity saving target probably had a more

clear view of the benefits.

However, it was quite noticeable that many

households participated in the Experiment not

because of a possibility to save electricity and

money. Many of them were also very interested in

keeping an eye on their own everyday electricity

use. For many households it was the most important

argument. Another example of the reason to partici-

pate in the Experiment was the possibility to be able

to see that the electricity bills were correct. Yet

another one was, for example, the possibility to

remotely watch that everything worked properly in

the summerhouse.

The interest in the motivation cases was proved

not to be very large however “The Balance” was

considered to be the motivation case that had helped

most participants to save electricity.

Finally, an inquiry was made to see how

Facebook had been used during the Experiment and

what kind of saving tips that had been submitted

during the motivation case period “Saving tips”.

Most of all Facebook was used for technical support

and other questions but the interest for this platform

soon declined.

Technical Measures. The Experiment had

influenced many participants to make small changes

in their homes like switching lighting to more

energy efficient but several families had also made

major changes, such as changing heating systems or

installing new white goods.

Approximately 66% of the participants answered

that they had carried out different technical measures

during the Experiment in order to save energy

(Taimor and Hols, 2013).

The responses also indicated that performing

technical measures was preferred rather than change

of the behaviour. Participants also seemed to use the

real-time display 100Koll a lot to ensure that the

measures they had undertaken really resulted in

energy savings.

Behavioural Changes. About 73% of the

participants said in the surveys that they had

changed their behaviour as a way of achieving

energy savings during the Experiment (Taimor &

Hols, 2013).

Again, the answers indicated that the participants

made bigger steps in behavioural adaptation than

they would if they were not involved in the

Experiment.

The survey answers indicated also that the

behavioural changes in the households did not affect

the indoor comfort or family’s living standard. Some

respondents mentioned however that the most

negative impact of the measures was reduction of

the indoor temperature.

Respondents also indicated that both their

partners and children often changed their energy

related behaviour during the Experiment.

Usability of the System. Although one-third of

survey respondents strongly agreed with the

statement that they only had few problems with the

feedback system during the Experiment, many

households used the opportunity to submit open

answers about the problems they experienced. At

least one-third of these comments indicated that the

equipment did not work correctly. Sensors reading

electricity consumption often lost contact with the

display. This means that nearly 20% of the

households had this problem. This might also have

affected the results of electricity savings shown on

the website because the estimation of electricity

consumption made by the company was based on

these readings.

Many participants stated that their knowledge

about household electricity consumption increased

due to the visualization and feedback.

Possible Improvements. Some improvements and

new options added to the service would, according

to the participants, additionally increase the value of

the service:

better contact between devices,

automatic updating of electricity price,

more smart plugs for measuring individual

outlets,

possibility of measuring the consumption of

fixed appliances e.g. heat pump,

TheExperimentHasShown-SetYourOwnGoalandsaveElectricity

183

better information about possible functions,

comparison with ‘normal’ values,

lighting of the display,

warning system for the temperature level - too

high or too low,

possibility of deciding saving targets

warning system for if the consumption is too

high for the goal to be achieved.

3.3 Future

There is a clear possibility that the participants

discovered some "electricity thieves" during the

Experiment and have started some major invest-

ments to reduce their electricity consumption during

the next heating season (2013-2014).

Many households were very interested to keep

the equipment after the end of the Experiment,

which promises well. Whether the participants will

continue to save electricity or will return to their old

habits, remains to be seen. A possible follow-up

after the winter 2013-2014 might give some

indication of the duration of electricity savings for

each group.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The following conslusions have been drawn from

the study:

Just over 50% of the participants made electricity

savings during the experiment compared with the

previous year; this group of customers saved an

average of 8% electricity.

Just over 22% of participants with a set energy

saving goal managed to reach the target; this

group saved an average of 15% electricity.

All the participants together made a saving of

0.7%.

All the customers from the control group

increased electricity consumption by 1.5 %.

30% of the households believed they had reached

their goals, while 55% did not know if they done

it or not.

Most people would benefit from the equipment

and the service in the future and would be

disappointed if it disappeared.

Most people were not afraid that it would be a

problem of privacy or integrity with company’s

access to the information about their electricity

consumption.

Slightly more than half of the households would

be willing to pay for a similar service in the

future.

Families with children were more willing to pay

for the service and more than others used the

consumption data to check the situation at home.

Those who achieved their electricity saving

target were willing to pay more for the service

than the others.

Many of the participants interviewed had made

some smaller or bigger modifications of the

heating systems.

Many of the participants interviewed had made

some small changes at homes like converting

light bulbs to more energy efficient.

Participants used Facebook but focused on

technical problems and issues.

E.ON used Facebook primarily to spread out

information about the Experiment and its

homepage.

The number of posts from participants dropped

sharply during the Experiment.

Almost 70% of the saving tips sent by the

participants were serious.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the staff of the

energy company E.ON Sweden for all their help and

support during the Experiment.

REFERENCES

Andersson, J., Larsson, P., 2012. Energy use and energy

feedback - Evaluation of the largest energy-saving

experiment at E.ON - Phase 1. Report LUTMDN/

/TMHP--12/5255--SE, Lund University, Lund. (in

Swedish)

Taimor, A., Hols, D., 2013. Energy use and energy

feedback - Evaluation of the largest energy-saving

experiment at E.ON - Phase 2. Report LUTMDN/

/TMHP--13/5267--SE, Lund University, Lund. (in

Swedish)

Uggmark, M., 2013. Scientific evaluation of the largest

energy-saving experiment at E.ON - Results. Report

LUTMDN/TMHP--13/5278--SE, Lund University,

Lund. (in Swedish)

E.ON, 2013. Website of the Experiment. Available at

http://experimentet.eon.se, December 15th, 2013.

SMARTGREENS2014-3rdInternationalConferenceonSmartGridsandGreenITSystems

184