Integrating Testing into Agile Software Development Processes

R. van den Broek

1

, M. M. Bonsangue

2

, M. Chaudron

3

and H. van Merode

4

1

JEM-id, Amersfoort, The Netherlands

2

LIACS – Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands

3

Chalmers – University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

4

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, Schipool, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Software Processes, Agile Development, Scrum, Testing, Agile Testing.

Abstract:

Although Agile methodologies have grown very popular, there is a limited amount of literature that combines

Agile software methodologies and testing, especially on how testing is integrated with Scrum. In this paper we

present an analysis of problem based on case study performed at the IT department of KLM regarding testing

in a Scrum team. After having triangulated our results with several interviews with external topical experts

and existing literature we propose a visual model that integrates testing activities in Scrum.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the last years more and more organizations

have started to adopt, or already have adopted, Ag-

ile methodologies for their software development pro-

cesses (VersionOne, 2011). The increased pressure

of the Internet industry on realizing a fast time-to-

market, designing flexible processes, and responding

to changing requirements poses several challenges to

organizations’ established software development ap-

proaches. Combined with the continuous struggle

software development teams face in the dilemma of

increasing productivity while also maintaining and/or

improving the quality of the software delivered (Lind-

vall et al, 2004), organizations and teams are moti-

vated to look out for new ways to develop their soft-

ware.

Agile methodologies build upon the values ex-

pressed in the Agile Manifesto (Cunningham, 2001)

and aim to achieve close customer collaboration, to

deliver business value as soon as possible in an incre-

mental manner, and to respond to changing customer

requirements (Barlow et al, 2011; Cockburn, 2003).

The methodologies captured under the umbrella term

”Agile methodologies” are not new concepts per se,

but the combination of existing best practices with

new techniques and a new mindset make them a re-

freshing and stable approach towards software devel-

opment. Although the benefits of Agile methodolo-

gies seem to be appealing, misinterpretations of the

Agile manifesto and/or inappropriate project contexts

can hinder teams in achieving their goals (Barlow

et al, 2011). Furthermore, various researchers have

recognized that there is no ”one size fits all” (Barlow

et al, 2011; Boehm and Turner, 2003a; Lindvall et al,

2004) methodology for software development, and or-

ganizations should assess both a project’s context and

the organizational context when selecting a suitable

development approach (Boehm and Turner, 2003b).

At the moment, the most frequently practiced Ag-

ile methodology is Scrum (VersionOne, 2011). Scrum

provides a lightweight process framework that can

be described in terms of roles (product owner, scrum

master, team), process (planning, iteration, review),

and artifacts (product and sprint backlogs, burndown

charts) (Schwaber and Sutherland, 2009).

Testing in Agile projects is different from tradi-

tional testing because of the continuous and integrated

nature of testing in the project lifecycle from the very

beginning (Crispin and Gregory, 2009; Lindvall et al,

2004; Talby, Keren, Hazzan, and Dubinsky, 2006).

Furthermore, because every iteration aims to deliver a

”potentially shippable” product, the developed func-

tionality within every iteration should be tested and

validated in order to assure that risks are covered.

Also the role of a tester in Agile projects changes sig-

nificantly with respect to the traditional role (Crispin

and Gregory, 2009; Kaner, 2004; Sumrell, 2007; Vis-

itacion, Rymer, and Knoll, 2009). Typically Ag-

ile projects do not have extensive requirements, nor

a complete architecture, but both evolve (and can

change) over time. As a consequence, testers must be

561

van den Broek ., Bonsangue M., Chaudron M. and van Merode H..

Integrating Testing into Agile Software Development Processes.

DOI: 10.5220/0004877105610569

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development (MODELSWARD-2014), pages 561-569

ISBN: 978-989-758-007-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

able to cope with evolving, incomplete requirements,

architectures, and products. Other challenges posed

to testers are the close team-collaboration, the in-

creased focus on test automation and regression test-

ing, and exploratory testing. Although the differences

between Agile testing and traditional testing are var-

ious, the test types and techniques that are applied in

Agile testing are not different from those applied in

traditional testing (van Veenendaal, 2010; van Vee-

nendaal, 2009). After all, the goal of testing is still to

verify that requirements are met.

The popularity of Agile methodologies has re-

sulted in a set of valuable scientific publications that

mostly report about case studies and experiences dur-

ing the introduction of Agile methodologies. How-

ever, the extent to which the focus has been specif-

ically given to the aspects of testing and quality as-

surance remains very limited. The only exception

we are aware of is (Karlsson and Martensson, 2009),

where a set of brief recommendations is proposed to

the existing test process. Relevant aspects that testers

need to know in Agile methodologies are also men-

tioned in (Astels, 2003; Beck, 2003; Crispin and Gre-

gory, 2009) and (Madeyski and Biela 2007; Madeyski

and Biela 2008). However, these publications remains

rather unclear on the way organizations starting with

Agile development should integrate their testing pro-

cesses.

In this paper we try to cover this gap, by identify-

ing the problem areas (Section 2), outline recommen-

dations (Section 3), and incorporate these in a model

(Section 4) that can be used by organizations to in-

tegrate their testing with Scrum. We have based our

observations on our experience on a project team at

KLM implementing Scrum as development method-

ology, and by visiting two other companies active in

the transportation sector. The results have been an-

alyzed using the grounded theory approach (Strauss

and Corbin, 1994), followed by the development of

a model how testing could be integrated with Scrum

and what practices/activities are recommended to im-

plement in future projects in order to enable a smooth

integration. The developed model and recommenda-

tions have been triangulated with external topical ex-

pert interviews, existing literature, and targeted inter-

views with KLM employees, as briefly explained in

Figure 1.

2 OBSERVATIONS

In this section we describe the case and the observa-

tions made during an implementation at KLM Scrum

as development methodology. We have categorized

our observations into five categories: project prepa-

ration, team composition, product backlog design,

sprint preparation, and product quality.

The project under observation was about the de-

velopment of a mobile web-application to be used by

KLM employees. The core Scrum team selected for

this project initially consisted out of 3 developers, 1

tester, a product owner and a Scrum master. In to-

tal, 7 sprints have been implemented over a period of

3 months whereby each sprint lasted two weeks. It

was the first time at KLM that test competence (CC

Test Management) was involved into an Agile devel-

opment process. Besides testers, also Business, In-

formation Management, and Operations were aligned

to the project in order to have a true cross-functional

group of stakeholders and to be able to pilot Agile

through the whole organization (and not just the IT

department).

2.1 Project Preparation

Project preparation turned out to be an essential as-

pect for the team to reach an efficient way of working

which, if not done properly, can result in a set of im-

pediments and waiting times. It is important to pre-

pare enough elements so that a team can efficiently

start sprinting.

In the project we observed there was no access to

test and acceptance environments before the first it-

eration started. The unavailability of these environ-

ments has caused several problems due to a delay of

5 weeks before resolving. First, the tests that were

actually executed were executed from a developer en-

vironment, thus demanding time from programmers

to prepare their environments. Although Agile ad-

vocates collaboration and interaction (Cunningham,

2001), this situation caused unnecessary delays for

both the tester and the programmer. Second, develop-

ment environments are not similar to test - or accep-

tance environments, thus questioning the value and

quality of the tests.

While Agile promotes communication about team

roles and personal expectations, the project at KLM

faced initial difficulties in overcoming the traditional

viewpoint of a tester’s tasks and responsibilities. In

combination with the unavailability of test environ-

ments the added value of the tester was not recog-

nized, eventually resulting in the termination of a

tester’s contract after 2 iterations.

Further, incomplete and unclear system depen-

dencies caused problems during the development and

testing of the application. It was not known which in-

teractions should be tested, what test data should be

used, and what the expected results of the test data

MODELSWARD2014-InternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

562

Figure 1: Research Methodology.

were supposed to be. Iteration 4 reported a change

in the deployment platform. Although Agile method-

ologies are capable of dealing with changing require-

ments (and so was the project team), platform require-

ments need some stability to avoid wasting valuable

time.

2.2 Team Composition

The project has seen the come and go of several differ-

ent team members. Due to a combination of the ear-

lier stated issues in total, three different persons have

been working as tester in the seven iterations of the

project, leaving periods of one to two weeks between

the exit and entry of the next tester. Furthermore, the

project has employed a total of five programmers with

an average involvement of 2.5 programmers per iter-

ation. With the absence of a tester in iteration 3, only

programmers and business stakeholders tested the ap-

plication (both not possessing the specific test skills).

Furthermore, after a new tester joined the project, the

defect data-trends in iteration 4 and 5 showed peaks

in the number of defects found. These peaks made it

difficult to complete all estimated user stories, given

that the team had not reserved time to resolve defects.

Of course, the entrance of a new member to the

team affects a team. Without previous project knowl-

edge new members need to orient themselves and dig

up assumptions the team already has, which takes

time and can hinder the flow of the team.

2.3 Product Backlog Design

Preparing the product backlog’s content for sprint

planning sessions was not implemented in a proper

way and caused meetings to overrun in time, cre-

ated tensions in these meetings, and contributed to the

lack of overview of the business. Initially, the prod-

uct backlog was not prioritized and user stories that

were placed on the product backlog were too large

in size. Subsequent sprint planning meetings priori-

tized user stories, but they were not concrete enough

for the team to be understood. More urgent was the

fact that some stories were also unclear to the business

stakeholders. The results were lengthy sprint plan-

ning sessions, high effort estimates because of uncer-

tainty, and shifting of the story’s priorities due to the

missing information.

Unclear user stories in sprint planning resulted in

changing sprint backlogs during a sprint, while de-

velopment and testing had already started (which is

against Agile). Occasionally, the content of user sto-

ries changed which resulted in additional rework.

2.4 Sprint Preparation

Sprint preparations aim to set the scope for the up-

coming iteration and to generate effort estimates for

this scope. Although a sprint’s preparation is related

to the product backlog design issues, there were more

aspects that hindered the team. Because of the peaks

of defects discovered in iteration 4 and 5 the team had

to concentrate on resolving defects during sprint plan-

ning rather than on the user story. As a result the time

spent on closing defects exceeded the time reserved

and only an average of 70% of the user stories was

concluded. Combined with the product backlog de-

sign issues, it resulted in programmers not knowing

what the business expected, and testers with difficul-

ties in designing and executing test cases that reflected

the business’ wishes.

To save time, those user stories of which accep-

tance criteria were discussed at sprint planning, were

not documented or stored in a systematical manner.

The result was that the acceptance criteria become

vague (or forgotten) and thus required a re-consult of

the business for re-clarification of already discussed

issues.

2.5 Product Quality

In Agile development it is a team’s responsibility to

deliver increments of a ”potentially shippable” prod-

uct that is continuously assured to be of high qual-

ity. Due to several impediments the team we ob-

served faced time pressures in the first two iterations,

IntegratingTestingintoAgileSoftwareDevelopmentProcesses

563

which resulted in the development of quick and dirty

solutions implying that code quality can get at risk,

potentially affecting the product’s quality. The deci-

sion in the tradeoff between resolving the problems

by code refactoring and implementing new function-

ality was not obvious. The first got the team’s pref-

erence, whereas new functionality had the business’

preference.

The demonstration at sprint 3 revealed some de-

fects that were not found during the sprint. Since

there was no tester present in the team on that sprint,

the overall product quality was questionable. Espe-

cially when the business gets to face defects that the

team is unaware of, convincement of putting a product

into production gets harmed. Further, technical doc-

umentation appeared to be incomplete making code

and technical decisions harder to understand

3 RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the observations and analysis outlined in

Section 2 we have produced a set of recommenda-

tions addressing the issues identified and aiming at

improving the integration of testing into Scrum-based

projects. Although each recommendation can be im-

plemented on itself, the combination of recommenda-

tions shows an interrelated set that complements each

other in the areas where difficulties have been experi-

enced.

3.1 Implement Sprint Zero

In order to deal better with preparation issues, Sprint

Zero

1

(also known as ’pre-iteration’, or ’iteration 0’)

can add value to the process by putting in place

enough elements for the team to achieve an efficient

and effective process. Although there is ”sprint” in

the name, the duration of this phase should not be

fixed but tailored to the characteristics and demands

of a project.

For teams and organizations new to Agile it is im-

portant to clearly communicate the changing project

roles (Sumrell, 2007) (especially the tester’s role),

and to manage expectations within, but also outside,

the team (Lindvall et al, 2004; West et al, 2010).

It has been recognized that although teams are self-

organizing they require a shared mindset, values and

principles (Fry and Greene, 2007). Training initia-

1

Jakobsen and Johnson (Jakobsen and Johnson, 2008)

see Sprint Zero as a kind of CMMI (Team, 2006) planning,

and state that the use brings more discipline to the project -

resulting in a projection of successes in larger Agile projects

tives and organizing workshops can help in attaining

this goal.

Following the vision of lean development (Pop-

pendieck and Poppendieck, 2003), waste in the soft-

ware development process should be minimized.

Teams interact with many, and depend on some, dif-

ferent organizational stakeholders and actors (Lind-

vall et al, 2004), that each can cause delays for the

project team when the team has failed to contact or

involve them in the project. In order to minimize the

effect of organizational stakeholders on the team and

the process, possible impediments they may cause

should be eliminated early on.

From a test perspective, sprint zero is an ideal time

to design a suitable test strategy. Outlining the over-

all approach towards testing focusing on the product’s

characteristics and risks, but also think of approaches

regarding defect management, test automation, and

regression testing. Furthermore, one might need spe-

cialist testers to do non-functional testing or access to

stakeholders to do user acceptance testing, which can

be reserved/contacted from the beginning.

As preparation to the project it is a good practice

to arrange the test infrastructure (environments and

tooling) before the first iteration starts. Not being able

to thoroughly test from the beginning hinders the true

continuous and integrated nature testing is supposed

to have in Agile development, and leads testing to lag-

ging behind on development immediately.

Although the overall IT architecture of large orga-

nizations is complex, dependencies should be identi-

fied between the system to be developed and the ex-

isting infrastructure. If not, the result can be long

waiting times to get the specifications and access, but

might also be implemented functionality that is based

on the wrong interactions (and thus requires rework).

During sprint zero, the Definition of Done (DoD)

(Claesson, 2011) should be designed in collaboration

with the project stakeholders in order to define when

a release, a sprint, or a user story is satisfied. Not

only can the team set the quality criteria and activities

that they think are required for each user story, iter-

ation, or release; but other stakeholders that interact

with the project/product in later stages such as main-

tenance can also contribute in, for example, cases of

technical documentation.

3.2 Implement Product Backlog

Grooming

Product Backlog Grooming sessions are intended to

review the product backlog before the next sprint

planning and can be used to address the problems re-

lated to the design of the product backlog and user sto-

MODELSWARD2014-InternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

564

ries. Furthermore, by executing it in a parallel fashion

to a running sprint, upcoming sprint planning sessions

are supposed to be relieved from lengthy discussions

and un-ready user stories.

During the grooming sessions user stories are an-

alyzed regarding their size, level of detail, and depen-

dencies. Large stories need to be sliced down and am-

biguous or incomplete stories should be corrected by

the Product Owner. Stories that contain dependencies

with other stories need to be carefully planned (e.g.

preferably not in the same sprint).

These sessions can further help the team in iden-

tifying what extra actions should be taken before

certain pieces of functionality can be implemented.

Whenever new requirements have been designed that

require additional tooling, test data, or environments,

actions can already be taken to prevent waiting time

in the next sprint. Finding out these things during a

sprint planning session may result in delays during

sprints (as occurred in the observed project).

To reduce costs, at least the Product Owner, the

Scrum Master, a tester, and one developer should be

be participating in grooming the product backlog. In

fact each of these participants add value through a dif-

ferent perspective, but especially a tester contributes

because of the critical perspective to get user stories

testable.

Given the fact that product owners and business

stakeholders may have difficulties in designing user

stories (Fry and Greene, 2007; Lindvall et al, 2004;

Seffernick, 2007; West et al, 2010) the adoption of

a Definition of Ready (DoR) is also recommended.

As is the case with the DoD, the DoR aims to set

quality criteria on a user story but this time to label

it as ’READY’. Previous research by (Jakobsen and

Sutherland, 2009) has showed that the DoR is able

to remove the waste caused by issues related to user

stories.

3.3 Use the Whole Team Approach

Our major recommendation is to have a tester in the

team and to keep the team constant for at least the du-

ration of the project. A constant team does not face

the delays that are related to people getting used to

the team and to the project and are thus better able to

learn as a team. Furthermore, with a multi-functional

team including a tester, continuity of product quality

is better assured because the test efforts can be uni-

formly distributed in all sprints.

Having a tester in the team contributes to the prod-

uct backlog design issues by providing a perspective

that is focused on the customer, but also takes into

account the technical problems that may occur during

development. The combination of the complementary

perspectives of programmers, product owner / stake-

holders, and tester, is also referred to as ’The Power

of Three’ (Crispin and Gregory, 2009). Furthermore,

testers are the ones that preserve the ’helicopter view’

over a product and are able to assess whether the over-

all quality would be acceptable to the business.

Although the entire team should be responsible for

testing, and testing should be a task that can be ex-

ecuted by any team member (Crispin and Gregory,

2009), our experience demonstrates that without a

tester the product’s quality might be at risk during

sprints: defect trends show an immediate increase

when a tester is not present in a team. Evans (Evans,

2009) supports the case for the value of the specific

test-skills a tester brings in order to deliver high-

quality software that meets the business’ needs. Ad-

ditional support is provided by (Sumrell, 2007) stat-

ing that everyone should be focused on quality and

that Agile testers are the ones infusing quality into the

team and the product throughout its lifecycle.

An often referred to model that is used for Ag-

ile testing, is ”The Agile Testing Quadrants” (Crispin

and Gregory, 2009). Originally, the model was de-

veloped by Marick (Marick, 2003) in order to distin-

guish the different type of tests that each serve dif-

ferent purposes. Without a tester in the team, it is

unlikely that the four quadrants are covered enough.

Programmers will be primarily focused on the first

quadrant describing technical tests that verify small

pieces of functionality. But business analysts and UI

designers will mostly focus on the third quadrant de-

scribing business tests focused on business scenario’s

and user interaction. This leaves two quadrants with-

out enough attention, namely the one on business tests

that verify whether user story’s acceptance criteria

are met, and the other on technical tests that verify

whether the non-functional requirements, or quality

attributes, are met.

For a team to implement a good ”Whole Team Ap-

proach” (Crispin and Gregory, 2009), it is important

to select a tester that fits Agile development and is

compatible within the team. The continuous and in-

tegrated nature of Agile testing, the team pressure on

delivering business value, and the team’s responsibil-

ity for quality are changing the role of a tester in Agile

projects. A skill of testers part of a Scrum team should

include knowledge about Scrum, hard skills (i.e. test

[automation] skills and acceptance test driven devel-

opment skills), and also good soft skills (i.e. commu-

nicative skills) because of the focus on individuals,

interaction, communication, and feedback (Cunning-

ham, 2001).

IntegratingTestingintoAgileSoftwareDevelopmentProcesses

565

3.4 Implement Acceptance Test Driven

Development

Implementing Acceptance Test Driven Development

(ATDD) can help teams in developing a good input

for test case design. ATDD resembles the practice of

extracting acceptance criteria, examples, scenarios, or

workflows from the product owner while discussing

the desired functionality of user stories. The goal of

the technique is to collect the test basis for user sto-

ries that can be enhanced to design test cases for these

stories immediately. Not only does the technique re-

sult in a test basis, it also facilitates and guides the

directions of the discussions.

From a test perspective, acceptance criteria are

important to identify given they are used to validate

functionality. Also, having acceptance criteria clear

and documented at the beginning of an iteration re-

inforces a programmer’s mindset and helps her/him

in developing a properly designed set of unit tests

through Test Driven Development (TDD).

But there is more value to find in practicing

ATDD: it significantly speeds up the process of de-

signing test cases and also has them resemble the

”real-world” better (Adzic, 2009). Furthermore, de-

pending on the nature of the test cases and the piece

of functionality, the tests can be transformed into au-

tomated tests to be executed efficiently and requiring

very little effort from a tester.

3.5 Focus on Value and Risk

Having traditional testing focusing primarily on the

risk areas, Agile development stresses the importance

of realizing business value. Although there is value in

covering those areas where business gets hurt most,

there are also other areas that may not be a high risk

but do deliver high value (i.e. benefits). Testing in Ag-

ile projects should thus not focus only on identifying

and covering ’risk areas’, but should also on identify-

ing and covering the ’value areas’. Functionality that

does not deliver direct ’damage’, but can deliver di-

rect ’benefits’ is as important to the business and thus

should be assured of high quality.

There exist several tools to help teams in defining

what is value for features. Initially, user stories were

designed to model functionality that provides value to

the business by requesting the writer to express who

the stakeholders are and why they want this function-

ality (Cohn, 2004). Adzic (Adzic, 2011) recognized

that there is a need to also have a project overview

of delivering value and introduced effect maps. An

effect map aims to guide a team in setting priorities

to those features that contribute most to the business

goals that were set. By using this tool and combining

this with a risk-value based test approach, both func-

tionality with high risks and high value are covered

by testing.

3.6 Start Test Automation Early

One of the first recommendations that is often made

to Agile teams is to start test automation early on. In-

vestments in the automation of tests will deliver pay

back in later stages by reducing the amount of time

required to execute tests. Automated tests are effi-

cient and consequent in execution and reduce the time

required for testing significantly. Especially regres-

sion testing can benefit from automation given the fact

that the regression test suite grows over time and will

reach a stage where testing can no longer keep up with

development.

However it is questionable whether test automa-

tion has to be applied in every project. For exam-

ple, for projects focussing on user interface on mobile

devices automation is difficult. Also, when a project

lifetime until maintenance is less than 3 months test

automation could be avoided. Finally, test automa-

tion requires a significant initial investment, and thus

it should be considered whether the Return on Invest-

ment (ROI) for test automation is positive. Teams

should consider the expected ROI of test automa-

tion during Sprint Zero, and question to what extent

maybe only parts of the test activities, such as prepar-

ing test data, can be automated.

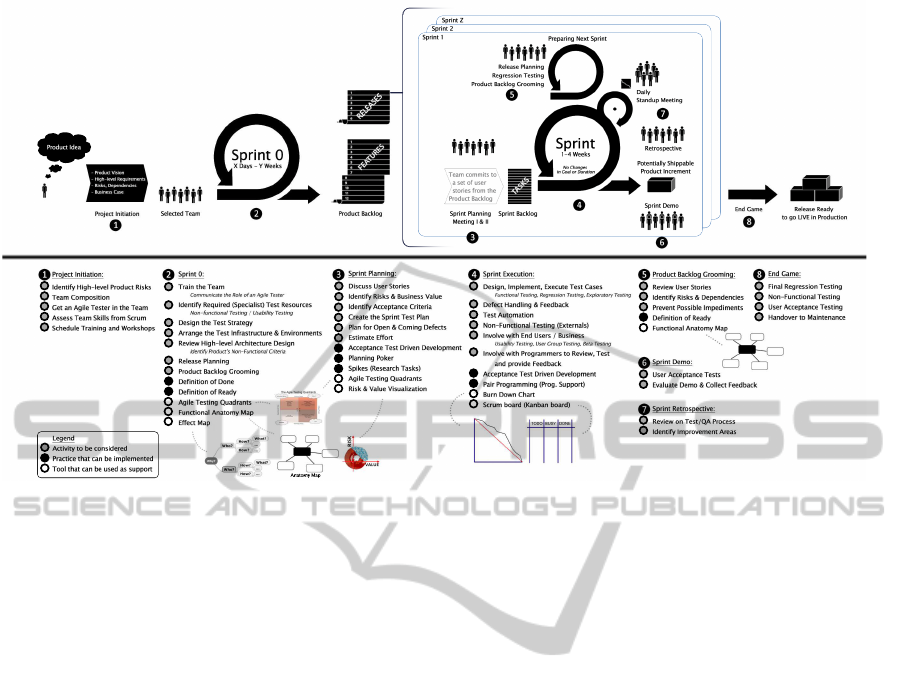

4 PROPOSED MODEL

To assist organizations (especially those new to

Scrum) with the integration of testing and QA activ-

ities with Scrum and the changing role of a tester in

Agile projects, we have developed a model that out-

lines the different aspects related to testing and QA

within the Scrum framework, see Figure 2 in the ap-

pendix. The rationale behind the model is based on

the project observations, the set of recommendations

outlined in Section 3, the interviews conducted, and

the academic literature consulted. Besides the chang-

ing role of a tester in Agile projects, we also see a

changing role for the test manager: a test manager

will be of a supportive role during the project when

it comes to, for example, the arrangement of test spe-

cialists and the test infrastructure, and will primarily

be actively involved in sprint zero.

The model distinguishes between the process

framework and a sub-layer of identified activities,

practices, and tools that relate to steps in the process.

MODELSWARD2014-InternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

566

Figure 2: The Scrum and Testing Framework.

Activities resemble the activities a team and testers

do during the development process; practices resem-

ble the identified practices that are recommended to

incorporate in the Scrum process; and tools resemble

means that can assist the team in performing its work.

Starting from the initiation of a project, we go

through an adjusted version of the general Scrum pro-

cess framework. As can be seen from the figure,

Sprint Zero has been included as we see it as an es-

sential phase for Scrum teams to be able to imple-

ment sprints in an efficient and effective manner from

the start. As stated before, the duration of Sprint

Zero can be flexible as long as the team gets prepared

well enough to start the first sprint. Besides taking

away possible impediments, communicating the role

of testers in the project, and arranging the required

test infrastructure, the team can develop a shared un-

derstanding about quality by defining the overall test

strategy, designing a good definition ready and a good

definition of done.

The inclusion of product backlog grooming and

release planning as clear steps in the process (and

as activities in sprint zero) stresses the importance

we again see in enough preparation. By eliminating

waste regarding the content and composition of user

stories in a timely manner, these activities aim to pre-

vent the team from unnecessary long sprint planning

sessions, ambiguous user stories, unclear priorities

and unclear content. Preparing the product backlog

for sprint planning sessions by timely reviewing also

trains the business in designing their stories in such a

way that they are accepted as ’READY’ by the team.

Following from good product backlog grooming, the

sprint planning sessions in their turn will be more fo-

cused on what they should be: finding out what it is

that the business really needs.

Following from a properly designed set of user

stories, the implementation of ATDD provides a valu-

able way to extract user stories’ acceptance criteria

and examples, which together are a valuable source of

input for test case design. By driving the dialogue be-

tween programmers, testers, and the business, ATDD

aims to guide the team to find out what it is that the

customer really wants (i.e. challenging the business),

what his or her true acceptance criteria are, and what

kind of real-world examples there might appear in

practice. Together with well designed user stories,

ATDD enables a team to develop a large part of test

case design before a sprint has even started.

The above three inclusions relate to the changing

role we see for a tester. Being integrated with the de-

velopment team and being involved with the project

from day 0, testers can add a lot of value to the team

as a whole. Although the added value of a tester may

be clear during the execution of a sprint given the re-

lation to traditional testing (i.e. test case design, ex-

ecution of test cases, defect management, etc.), we

especially see opportunities for testers to add value to

the team during sprint zero, product backlog groom-

ing, and sprint planning sessions.

The model contains several notions of risk and

value based testing in sprint zero, sprint planning,

IntegratingTestingintoAgileSoftwareDevelopmentProcesses

567

and product backlog grooming. We see the focus on

both risks and value as an important switch compared

to the traditional risk-perspective. In order to create

a consistent focus throughout the entire project, we

state that teams should start to identify business value

and priorities of desired functionality in sprint zero.

A tool through which this can be done is the effect

map (Adzic, 2011), outlining the relationships be-

tween functionality, stakeholders, and business goals

(i.e. the value the project wants to generate). Know-

ing the value that can be realized by specific pieces

of functionality, the test planning for one iteration can

map the combination of the risks and the value in user

stories in order to set the priorities for testing and in

this way ensuring that the test effort is focused on the

most important aspects for the business.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we present an empirical study that ex-

poses the difficulties that were faced by a project at

KLM regarding the integration of testing with Scrum.

Based on the project observations, additional inter-

views, and existing literature we have analyzed the

problem areas and propose a set of recommendations

that help organizations to integrate their testing into

Scrum. The recommendations are maybe common

sense and when seen in isolation they are not neces-

sarily novel. Our contribution is in complementing

the recommendations by developing a model that ex-

tends the common known Scrum framework in order

to map the activities, practices, and tools that are re-

lated to testing and quality assurance.

We have not included experimental results to vali-

date our framework, because to draw general conclu-

sions about the added value of the proposed model

a large number of development teams in different

contexts would have to be observed and measured.

However, in order to prevent threats to the valid-

ity of our findings, we have taken several measures.

First, to preserve construct validity and internal va-

lidity, we have consulted multiple sources during

the development of the model: literature, expert in-

terviews, project observations, and workgroup ses-

sions. Second, the interviews and project observa-

tions have been transcribed, coded, and analyzed fol-

lowing the grounded theory approach (Strauss and

Corbin, 1994). Third, to preserve external validity,

two similar companies have been visited, external ex-

perts have been consulted and literature was used in

order to prevent any bias.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank KLM for providing the op-

portunity to observe a real-life project implementing

Scrum and all interviewees that have freed their valu-

able time to help us in our study.

REFERENCES

G. Adzic. Bridging the Communication Gap: Specifica-

tion by Example and Agile Acceptance Testing. Neuri

Limited, 2009.

G. Adzic. Agile product management using Effect Maps.

Agile Record The Magazine for Agile Developers and

Testers, 2011.

D. Astels. Test-Driven Development: A Practical Guide.

Pearson Education Inc., 2003

J. B. Barlow et al. Overview and Guidance on Agile Devel-

opment in Large Organizations. Comm. of the Ass. for

Inform. Systems, 29(1):25–44, 2011.

K. Beck. Test Driven Development: By Example. Pearson

Education Inc., 2003

B. Boehm and R. Turner. Balancing Agility and Discipline:

A Guide for the Perplexed. Addison-Wesley Pearson

Education, 2003.

R. Boehm, B. Turner. Using risk to balance agile and plan-

driven methods. Computer, 36(6):57–66, 2003.

A. Claesson. Test Strategies in Agile Projects. In EuroSTAR

2011, 2011.

A. Cockburn, L. Williams Agile software development:

it’s about feedback and change IEEE Computer,

36(6):39–43, 2003

M. Cohn. User Stories Applied: for Agile Software Devel-

opment. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2004.

L. Crispin and J. Gregory. Agile Testing: a Practical Guide

for Testers and Agile Teams. Addison-Wesley Profes-

sional, 7th ed., 2009.

W. Cunningham. Agile Manifesto, 2001.

http://www.agilemanifesto.org.

D. Evans. How to Succeed in an Extreme Testing Environ-

ment. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

C. Fry and S. Greene. Large Scale Agile Transformation in

an On-Demand World. In AGILE 2007, pages 136–

142. IEEE, 2007.

C. R. Jakobsen and K.A. Johnson. Mature Agile with a

Twist of CMMI. In Agile Conference, 2008, pages

212–217. IEEE, 2008.

C. R. Jakobsen and J. Sutherland. Scrum and CMMI: Going

from Good to Great. In Agile Conference, 2009, pages

333–337. IEEE,2009.

C.J.D. Kaner. The Ongoing Revolution in Software Test-

ing. Software Test & Performance Conference, Seat-

tle, 2004.

E. Karlsson and F. Martensson. Test Processes for a Scrum

Team. Master’s thesis, Lund University, Sweden,

2009.

MODELSWARD2014-InternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

568

M. Lindvall, et al. Agile Software Development in Large

Organizations. IEEE Computer Society, 4:26–34, De-

cember 2004.

L. Madeyski and W. Biela. Empirical Evidence Principle

and Joint Engagement Practice to Introduce XP In

Proc. of Extreme Programming and Agile Processes in

Software Engineering volume 4536 of Lecture Notes

in Computer Science, pp. 141–144, Springer, 2007.

L. Madeyski and W. Biela Capable Leader and Skilled and

Motivated Team Practices to Introduce eXtreme Pro-

gramming in Proc. of Balancing Agility and Formal-

ism in Software Development, volume 5082 of Lec-

ture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 96–102, Springer,

2008.

B. Marick. Exploration through Example. http://

www.exampler.com/old-blog/2003/08/21/.

M. Poppendieck and T. Poppendieck. Lean Software De-

velopment: An Agile Toolkit. Addison-Wesley Pro-

fessional, 2003.

K. Schwaber and J. Sutherland. Scrum guide. Scrum Al-

liance, Seattle, 2009.

T. R. Seffernick. Enabling Agile in a large organization: our

journey down the yellow brick road. In Agile Confer-

ence, 2007, pages 200–206. IEEE, 2007.

A. Strauss and J. Corbin. Grounded theory methodology:

An overview. Sage Publications, 1994.

M. Sumrell. From Waterfall to Agile - How does a QA

team transition? In Agile Conference, 2007, pages

291–295. IEEE, 2007.

D. Talby, A. Keren, O. Hazzan, and Y. Dubinsky. Agile

Software Testing in a Large-scale Project. Software,

23(4):30–37, IEEE 2006.

C. P. Team. Cmmi for Development, Version 1.2. 2006.

E. van Veenendaal. Scrum & Testing: Back to the Future.

Testing Experience, 3, 2009.

E. van Veenendaal. Scrum & Testing: Assessing the risks.

Agile Record, 3, 2010.

VersionOne. State of Agile Survey 2011 - The State of Agile

Development. 2012.

M. Visitacion, J. R. Rymer, and A. Knoll. A Few Good

(Agile) Testers. Forrester Research Inc., 2009.

D. West and et al. Overcoming the Primary Challenges Of

Agile Adoption. Forrester Research Inc., 2010.

IntegratingTestingintoAgileSoftwareDevelopmentProcesses

569