Networks of Pain in ERP Development

Aki Alanne

1

, Tommi Kähkönen

2

and Erkka Niemi

3

1

Department of Information Management and Logistics, Tampere University of Technology, Tampere, Finland

2

Software Engineering and Information Management, Lappeenranta University of Technology, Lappeenranta, Finland

3

Information and Service Management Department, Aalto University School of Economics, Helsinki, Finland

Keywords: ERP, Development, Network, Interpretive Qualitative Case Study, Challenges, Stakeholders.

Abstract: Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems have been providing business benefits through integrated

business functions for two decades, but system implementation is still painful for organizations. Even

though ERP projects are collaborative efforts conducted by many separate organizations, academic research

has not fully investigated ERPs from this perspective. In order to find out the challenges of ERP

development networks (EDN), a multiple case study was carried out. We identified three main categories of

pain: evolving network, inter-organizational issues, and conflicting objectives. The dynamic nature of the

EDN causes challenges when new organizations and individuals enter and leave the project. Relationships

between organizations form the base for collaboration, yet conflicting objectives may hinder the

development. The main implication of this study is that the network should be managed as a whole in order

to avoid the identified pitfalls. Still more research is needed to understand how the EDN efficiently interacts

to solve different problems in ERP development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recently, both researchers and practitioners have

paid a great deal of attention to Enterprise Resource

Planning (ERP) (Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009). ERP

offers organizations an all-in-one solution for the

seamless integration of information flow across the

organization and, as a result, increased

competitiveness (Davenport, 1998). ERP research in

Information Systems (IS) has focused on areas such

as critical factors (Al-Mashari et al. 2003), failures

(Barker and Frolick, 2003), organizational

development (Berente et al., 2008), and

organizational fit of ERP (Hong & Kim, 2002).

Moreover, it was noted in the literature already a

decade ago that implementation projects are prone to

failure, lead to cost overruns, and, in the worst-case

scenario, to project cancellations (Pekkola et al.,

2013). Unfortunately, examples of ERP project

failures are not difficult to find, see e.g. Hershey,

Nike, or HP (CIO, 2009). In fact, it has been

estimated that more than 90 percent of ERP

implementations are unsuccessful to some degree

(Momoh et al., 2010). Due to contemporary

practices, ERPs are often developed in networks of

organizations that comprise a multitude of

stakeholders from different levels of each of the

organizations (Dittrich et al., 2009). The network

aspect of ERP development has not, however,

gained enough attention in ERP research

communities.

In this paper, the challenges in ERP development

are investigated by examining the ERP development

networks (EDN) of three large enterprises. The

research question is as follows: what kind of pain

can be identified in ERP development networks? To

accomplish this, we conducted an interpretive case

study comprising 43 semi-structured interviews.

In section 2, the findings from a review of the

related research are presented. Section 3 introduces

the case organizations and the research approach.

Section 4 presents, the findings from an analysis of

the data. In the discussion section, the findings are

elaborated on and linked to existing literature.

Finally, the conclusions section highlights our key

findings and suggests areas of future research.

2 RELATED RESEARCH

An ERP system is a packaged information system

that provides, through a process-oriented view, an

257

Alanne A., Kähkönen T. and Niemi E..

Networks of Pain in ERP Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0004890002570266

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 257-266

ISBN: 978-989-758-028-4

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

integrated solution for an organization’s information

processing needs that enables the organization to

efficiently manage its use of resources (Nah et al.,

2001).The implementation of an ERP system affects

most parts of the organization and usually involves

external stakeholders (Davenport, 1998). Together,

these actors form a development network that

comprises all actors starting from the flagship

organization (e.g. SAP) to the users in the adopting

organization (AO) (Dittrich et al., 2009; Sarker et

al., 2012). There may also be various other actors

from different organizations that provide diverse

areas of expertise, e.g. implementation consultants

or offshored developers (Dittrich et al., 2009; Ernst

and Kim, 2002). Communication and interaction

between these actors are prone to errors and

misunderstandings (Sarker and Lee, 2003).

The development networks, their problems, and

interactions are understudied in IS literature.

Previously, these global networks were approached

from a general business perspective (Ernst, 2010),

from a global vendor’s and its partners’ perspective

(Sarker et al., 2012), or based on human

communications research from single companies’

internal perspective while separating the network

from the development activities (Isomäki and

Pekkola 2010).

To highlight the pain in ERP development, we

have drawn on the literature that describes the

critical factors in ERP implementation. A

preliminary literature review revealed a large

number of IS papers that were concerned with

critical factors and other impediments in ERP

implementation. None of them, however, explicitly

focused on network related issues, except for Nour

and Mouakket (2011). Instead, they investigated

factors from a multi-stakeholder perspective,

mapping the factors identified from the literature to

proposed fundamental stakeholders in ERP

implementation. We, on the other hand, used the

literature on critical factors to assemble a holistic

picture about the possible issues encountered in ERP

implementation in general.

Six articles (Al-Mashari et al. 2003; Amid et al.,

2012; Dezdar and Sulaiman, 2009; Kim et al., 2005;

Momoh et al. 2010; Shirouyehzad et al., 2011) were

chosen as the starting point from which to gather the

general ERP challenges from the literature. Forward

and backward searches were also applied when

considered necessary (Webster and Watson, 2002).

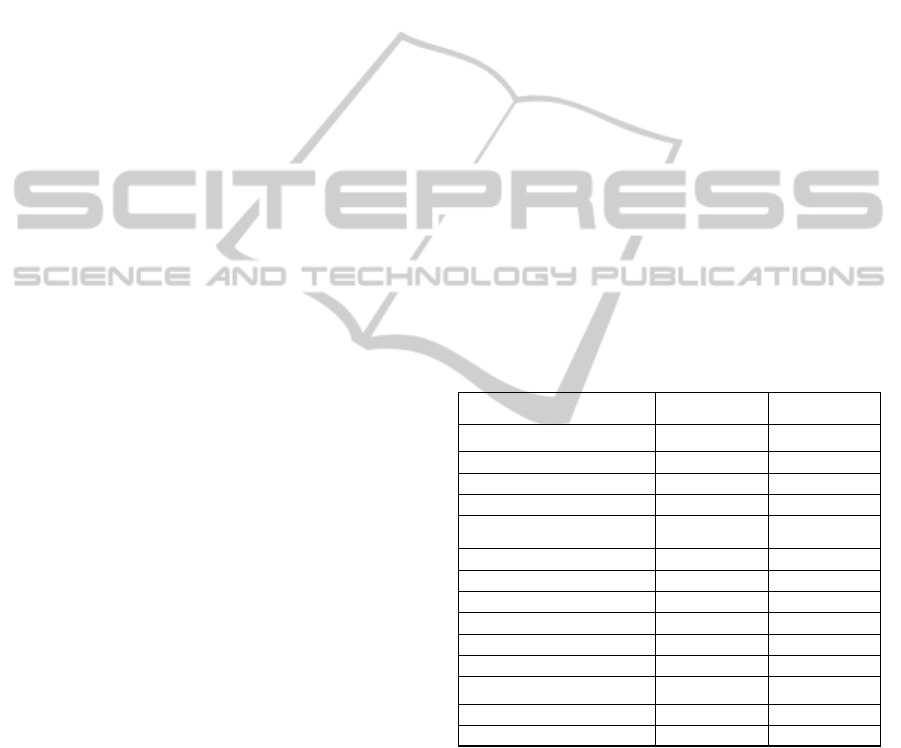

The pain in ERP development was divided into

eight categories comprising 40 issues. The

examination of these issues strengthens the earlier

observations that the current literature does not pay

Figure 1: Pain in ERP development.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

258

much attention to network-related issues. For clarity,

the themes are labeled alphabetically and the issues

under them are numbered accordingly. The findings

are presented in Figure 1.

3 RESEARCH APPROACH

An interpretive case study approach (Walsham,

1995) was selected in order to gain in-depth

knowledge on EDNs. Data was gathered from three

different organizations to identify characteristics and

issues related specifically to ERP development

networks rather than idiosyncratically to a certain

organization. The interviews were conducted

between January and June 2013 and analyzed

between June and September 2013.

3.1 Case Organizations

Case A is a large, global manufacturing organization

with almost 30.000 employees. In the mid-1990s,

the company initiated a customized ERP system for

sales and logistics to replace the legacy systems. The

existing ERP products on the market did not support

the specialized business processes. The project

encountered many challenges that included

architectural redesign and a merger with another

company. These challenges resulted in both budget

and schedule overruns. The system is currently in

use in its intended scope and it is still being

developed in cooperation with the original vendor.

Case B is a global service provider in the retail

business with over 1.000 employees. The company

is currently renewing its ERP system with a

customized solution because the old system no

longer supported the critical business processes. The

company and the vendor have had a history of

cooperation for over 15 years. The same vendor also

provided the previous ERP system. The current

project was initiated in 2008 and at the time of the

writing of this paper it was in the pilot phase with

initial rollouts.

Case C is a globally operating manufacturing

organization with over 20.000 employees. It decided

to implement a customized ERP system for its raw

material procurement business together with a

vendor. The initial planning was started in 2003 with

the actual project kick-off in 2006. The first version

of the system went live in 2008. At the time of

writing this paper, the company was continuing to

invest heavily in project and maintenance work to

further improve the system. The system was rolled

into new geographical areas in 2011.

3.2 Data Collection

Data collection began in each case organization with

an initial interview with our main contact person

(e.g. CIO). The rest of the interviewees were chosen

with snowball sampling. Additionally,

organizational charts were studied in order to

consider all the relevant stakeholder perspectives.

The interviewees, their work profiles, and

organizations are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: The work profiles of the interviewees.

Inter-

viewees

Business

IT

ERP

vendor

3

rd

party

Tot

al

Case A

2 6 7 2 17

Case B

7 5 4

- 16

Case C

6 4 - - 10

Total

17 13 11 2 43

The content of the interviews was based on the

preceding literature review. Each interview was

conducted onsite at the case organization. The

interviews lasted from 11 to 111 minutes, and the

average was about one hour per interview. The

interviews were recorded and transcribed for

analysis purposes. The researchers also collected

secondary research material such as documents and

reports to better understand the context.

3.3 Data Analysis

One dedicated researcher was responsible for the

data analysis of each EDN. The following analysis

method was chosen because of the data-driven

approach and cooperation of the three researchers.

First, the responsible researcher identified and

categorized the ERP development challenges from

the data. Second, the researchers compared the

categories with each other in several brainstorming

sessions in order to find similarities and differences

as well as to agree on common categories for the

analysis. Third, due to the network perspective, the

challenges that could occur in in-house development

without the presence of EDN partners were

excluded. As a result, three main categories and

eleven subcategories were identified. Finally, the

findings were compared with the existing literature

in order to understand the theoretical implications.

NetworksofPaininERPDevelopment

259

4 FINDINGS

“You most likely know the critical success factors of

an ERP project? We failed them all.“ –Case C, AO

The resulting three most essential categories and

their sub-categories are presented below. Some

categories are in practice intertwined, but to improve

clarity they have been divided.

4.1 Evolving Network

“We have lost some of the key persons [with 20

years’ of experience] already before. It always stops

the development like hitting a brick wall.” –Case C,

AO

The EDN of each case organization has evolved

at three levels during the ERP system development.

The network can evolve at the organizational level.

Also, structural changes in the organization or

environment of the EDN can introduce additional

challenges for ERP development, as can individual

people entering and leaving the projects for various

reasons.

4.1.1 New Organizations Involved

The development has involved business partners and

external stakeholders such as vendor subcontractors

and implementation consultants. Some of these

organizations have had a periodic role in the

development:

“We have done it in several waves. The latest

one, I can’t remember the name of the firm, we

designed the layouts together and they made the

models and designed the usability.” –Case B,

Vendor

“We purchased consulting services for the initial

planning, but I can’t remember who or which

company it was.” –Case C, AO

AO in Case A ended up in a conflict with a

database vendor:

“And things ran smoothly with [the original

database vendor] for a couple of years but then they

became a little greedy at some point and the license

fees starting increasing a little too much and they

weren’t as flexible anymore so we decided to,

[switch the vendor]” –Case A, AO

The periodic presence of organizations increases

the complexity of the EDN at the organizational

level, and thus possibly complicates the overall

management efforts.

4.1.2 Structural Changes in Organizations

Structural changes in an organization can hinder the

ERP development. For example, a merger changed

the original scope of the system in Case A:

“Then we had a project phase with severe system

architectural issues. The original scaling,

implemented with the technology of the time, was

insufficient for production use at the scale of our

company at that time, as the merged company.” –

Case A, AO

The merger also introduced competing systems.

Upper management had to decide which system to

abandon and which system to develop further. The

length of time before a decision was made resulted

in a period of uncertainty. Even organizational

changes on a smaller scale can change the roles and

relationships:

“We had a very good network of specialists,

coordinators, super users, and users but the co-

determinations killed the whole thing” –Case C, AO

In addition to the changes in AO, structural

changes in the vendor organization were also seen as

a challenge to ERP development. The structural

changes were the result of the continuously

increasing number of employees, new operating

models, and the offshoring of operations. These

actions introduce difficulties:

“The vendor and we have changed organizations

so that I could not contact him, but instead someone

who doesn't know anything about the issue.” –Case

C, AO

4.1.3 Involvement of Individuals

The EDN constantly evolves on an individual level.

Some of the individuals were identified as being

crucial for the ERP project because of their

experience and tacit knowledge. Thus, their absence

creates a void that further disrupts the project

dynamics:

“…there was a clear dip in performance when he

[project manager] left, there was no single person

who has the 13 years’ of experience about the

system.” –Case B, AO

The role of key persons was further emphasized.

If a key person decides to leave, it can take a long

time to train a new person – even with a help of

good documentation:

“Just before a new go-live, one important

business stakeholder moved to another country and

another person responsible for the specifications

retired. Even though we had pretty good

documentation we lost a lot of important knowhow.”

–Case C, AO

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

260

Additional challenges were due to changes in the

involvement of different people in different project

phases. For example, the business representatives

present in the specification phase were different

from those in the verification phase.

“There were over 100 persons during the busiest

implementation phase, but only a handful of the

original are here anymore.” –Case C, AO

“As the project dragged on and ran into

complications, I must say that the business people

disappeared along the way” –Case A, AO

This caused confusion and misalignment of

needs, and, as a result, extra work was needed to re-

establish the personal relationships between

individuals, after changes in involvement.

4.2 Inter-organizational Issues

“We have understood for a long time that we are in

a kind of a forced marriage” –Case A, AO

As ERP development is a cooperative effort

carried out by a dynamic EDN, the relationships

between different organizations are of major

importance. Misunderstandings, unevenly divided

power, and vendor incompetence were identified as

challenges in these relationships. The development

model formed by the network and third party

relationships were also considered to be problematic.

4.2.1 Long-term Relationship with Vendor

In all cases, a long-term relationship between vendor

and AO was identified, and both history and

personal ties determined this relationship. The

vendor-AO relationship turned out to be significant

in terms of impact on development activities.

In Case A, the relationship was described as a

“forced marriage”. The AO had even considered

buying the source code of the system from the

vendor. In the project phase, a very solid project

group was established and development was done in

close cooperation, whereas currently the vendor

would like to have more direct contact with the

AO’s business. Also, the constant cost cutting of the

AO has forced the vendor to continuously optimize

its processes and to outsource the development to

low-cost countries.

History between the AO and vendor can affect

the development process. For example, in Case B

some features are made “off-the-record” to satisfy

the AO. However, the long-term relationship can

also cause problems. For example, in Case B the AO

had “blind trust” in the vendor’s knowledge both

about project management and business logic in the

initial development phases. This resulted in a

miscalculation of the resources required and to

misfits between the system and business processes.

Also, in Case A, trusting too much on a vendor’s

expertise when choosing the system’s base

technologies was a mistake because the system

encountered architectural problems during the initial

rollouts.

4.2.2 Misunderstandings

Misunderstandings between stakeholders hindered

the development:

“There was a completely wrong illusion about

the situation.” –Case C, AO

In Case B, the vendor saw the project phase as

piloting while AO management considered it to still

be planning and development because half the

modules were missing. Other misinterpretations

concerned the number of missing features; the

vendor saw that most of the necessary features were

in place: “At the moment we have an understanding

that there shouldn’t be a long list of new features”

while the AO thinks these are just the initial ones

“we have four years of development needs waiting”.

Furthermore, in Case A, achieving a common

understanding was initially challenging:

“I was talking about the fence pole and they

were talking about the fence. We had agreed on

completely different things and neither of us

understood anything.” –Case A, AO

4.2.3 Unevenly Divided Power

In Case B, there are considerable differences in size

and revenue between the vendor and the AO. Thus,

the AO is able to dictate the order in which new

features for the system are developed:

“We have a pressuring means towards that end

[vendor], so that all the other doings will stop if we

have that kind of [major] problem.” –Case B, AO

In Case C, the situation is reversed as the AO is

struggling to keep the vendor’s competent personnel

in the project:

“At the moment, we have to cut our investment

budget and we're really afraid to lose the key

resources at the vendor side. We know that they will

be allocated to different projects if we can't give

them enough work.” –Case C, AO

Unlike with Case B, in Case A the power

relationships between the AO and vendor are more

even. It was estimated that the failure of the ERP

project would have caused serious consequences for

both sides:

“I would say so that what saves these kind of

NetworksofPaininERPDevelopment

261

projects is the situation where [AO] and vendor are

both equally in trouble…Then there is the will to go

forward.” –Case A, Consultant

4.2.4 Vendor Incompetence

The vendor’s incompetence was highlighted as one

of the challenges in ERP system development. The

vendor’s ability to manage the overall development

was criticized in Case B. According to the AO,

“vendor has too many things and changes going

on”. The vendor has not been able to allocate

resources properly because the scope of the project

has not been fully realized. Furthermore, the vendor

has not been able to create a roadmap for the system

and that has caused problems for the whole EDN.

”By roadmap I mean that the vendor could have

clearly stated when certain stages are finished and

what those will include…That has been the

challenge.” –Case B, AO

Further, due to poor testing practices, too many

errors have been found when piloting the system.

New versions have caused old functionality to break

and the load on the system has not been calculated

properly.

In Case A, the vendor had a lack of well-

established practices in the beginning of the project.

Because of insufficient testing, the first deployment

of the system failed. According to consultants, the

vendor conducted the testing in an unrealistic

environment. Consultants entered the project to

cooperate with the vendor to solve the problems

caused by non-scalable system architecture. This

cooperation was difficult in the beginning:

“Practically, they didn’t have a clue how to

make it work… They developed it in a vacuum and

when we looked at it, it seemed that the way of

implementing the system… was completely wrong.”

–Case A, Consultant

4.2.5 Development Model

A development model includes practices and

processes for carrying out the cooperative

development between the stakeholders in the EDN.

The development model was causing problems:

“The customer and vendor are partially working

in their own silos. On a personal level, the co-

operation is good but we are not sure if this is the

most efficient and optimal way of working.” –Case

C, AO

In Case A, it appeared that establishing a solid

project group between the AO and the vendor was

considered challenging:

“I was leading the project at the customer side

and the vendor had their own leaders… it was

messed up completely… The biggest challenge was

to get rid of the mind-set of ‘we pay and you

deliver’.” –Case A, AO

The vendor on the other hand criticized the

current development model for being too slow until

the requests are turned into features of the system.

Similarly, a representative of Case C criticizes the

issue management:

“It takes about two-three weeks if I create a

service ticket before someone from India starts

calling and doesn't understand anything.” –Case C,

AO

Furthermore, in Case A, the AO and the vendor

created separately the business and technical

roadmaps of the ERP system. The vendor saw this as

a mistake and emphasized the closer cooperation:

“Their business is a customer to their IT, and

our customer is their IT organization. This is the old

model that we've stuck with.” –Case A, Vendor

4.2.6 Relationships with Third Parties

Relationships with third parties in the EDN can

cause additional challenges for the development. In

Case A, consultants estimated that both the AO and

the vendor were relying too much on the solutions of

large database vendors whose products they were

already familiar with. Later, the chosen technology

turned out to be insufficient.

Because ERP systems integrate with the systems

of third parties, additional organizations may

become involved in the EDN. In Case B, integrating

the ERP with the systems of two business partners

was seen as especially challenging. In addition, in

Case C, a major integration challenge has emerged

due to a possible need to include the standardized

interfaces of a third party in the system.

4.3 Conflicting Objectives

“The local director hated the system and didn't want

it…They didn't say it in public but that's how it

was.“ – Case C, AO

Conflicting objectives turned out to be a major

issue in ERP system development: the vendor’s dual

objective, ownership issues, and power relationships

hindered the decision-making.

4.3.1 Dual Objective of the Vendor

The vendor can have a dual objective: to customize

the system to serve the AO’s needs and to

simultaneously build a general product for other

clients. In Case A, the initial plans for making the

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

262

product were discarded, as the amount of custom

logic made specifically for the AO increased:

“We should have thought more clearly about

whether we are making a product or a customized

system… That’s one of the basic things that

distracted the project.” –Case A, Vendor

Similarly, the vendor in Case B saw that when

making a product, compromises needed to be made:

“My role began with starting to chew that wish

list [of specifications], thinking about how we can

fulfill those wishes with our new product...So it’s a

kind of balance, how many of them can become

general features. And some flexibility, that the AO

can be flexible about some things that we can make

them general features that we can’t make everything

according to their wishes.” –Case B, Vendor

However, it seemed that the vendor lacks the

resources to accomplish both of its goals, especially

if the needs of other clients acquiring the product are

conflicting with the AO’s requirements. This easily

leads to tensions between organizations:

“It is annoying to pay for some basic

functionality which you have in a way developed,

and afterwards other clients may of course buy it for

some package price but they would never buy that

plus this [the development work].” –Case B, AO

Also in Case C, an interviewee commented on

how the vendor could benefit the competitors:

“If the vendor learns something new during this

project, they can reuse the ideas with the

competitor.” –Case C, AO

4.3.2 Internal Conflicts in the AO

Internal conflicts inside the AO can introduce

additional challenges for ERP development.

Different business functions may have conflicting

needs and managing these needs within one system

is not easy. As an extreme example, when Case A

went through a merger during the project, power

relationships changed and some functional areas

came under different leadership:

“They [logistics] started making separate

islands … they wanted to “freeze” the system to a

certain point and started to include all kinds of

additional systems there. It has been ongoing for ten

years now and we have ended up with serious

problems …” –Case A, AO

Additionally, because of scarce resources, it was

found that multiple simultaneously ongoing projects

disrupted the ERP development. For example, in

Case B the objective is to implement a new

operating model along with the ERP. Since these

projects were in different phases and managed by

different personnel, misfits occurred, e.g. business

project people considered the project as a clean slate

approach while the IT department sees it as using the

old system as a basis for development, even though

their alignment is considered essential.

5 DISCUSSION

Even though ERP research has reached a certain

level of maturity (Schlichter & Kraemmergaard,

2010), ERP projects often still exceed schedules and

costs, heavily (Amid et al., 2012; Momoh et al.,

2010). Most of the literature on ERP challenges

focuses on the AO while vendor and network related

issues are given less attention. Our findings,

however, suggest that issues caused by networked

development are in fact relevant for an ERP project.

We compared our findings with the literature

synthesis presented in Figure 1 and mapped the

issues overlapping with our sub-categories (Figure

2). Four categories have already been fairly well

documented in the literature, and four categories are

found at least on some level. Our study has also

revealed three new categories of issues that hinder

the development activities in such networks.

Figure 2: Findings mapped with the existing literature.

Evolving Network. Frequent changes in key users or

building and retaining a competent ERP project team

are found challenging (Amid et al., 2012), yet they

focus on the individual level. We found that

equivalent issues are also caused on the group and

organizational level. Changes in the AO’s business

environment add challenges to ERP development

(Kim et al., 2005; Momoh et al., 2010). Our findings

indicate that structural changes, e.g. switching

Identified pain Literature coverage

References (as

labelled in Fi

g

ure 1

)

EVOLVING NETWORK

New Organizations Involved NO -

Structural Changes in Organizations PARTLY G3

Involvement of Individuals YES F6, H4, H6

INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL

RELATIONSHIPS

Long-Term Relationship with Vendor PARTLY A3, E3

Misunderstandings YES A5, D3

Unevenly divided power NO -

Vendor Incompetence YES A3, B5, B6

Development Model PARTLY A4, D2, G2, H4

Relationships with Third Parties PARTLY A2

CONFLICTING OBJECTIVES

Dual Objective of the Vendor NO -

Internal Conflicts in the AO YES A1, F5, E4

NetworksofPaininERPDevelopment

263

operating model or outsourcing operations, within

the vendor organization may also introduce

problems. ERP development in networks becomes

challenging as new organizations become involved,

but no references from the literature was found to

support this. In addition, the changes in the network

cause other types of challenges to emerge, e.g. the

temporary involvement of third parties may set

certain pressures for documentation standards and

communication methods.

Inter-organizational Issues. Distrust between

partners and external parties’ lack of industry

competence are obstacles for successful cooperation

(Al-Mashari et al., 2003). Due to long-term

cooperation, these were not identified as problems.

In our study, trust was often the term used to

describe the relationship between the AO and the

vendor. Surprisingly much trust about business

processes is placed on the shoulders of the vendor.

This, however, introduces new challenges for ERP

development, e.g. stakeholders’ competence is taken

for granted and formal cooperation methods are

bypassed. At worst, this leads to a misalignment of

the development activities, and thus distracts the

cooperation within the EDN.

Generally, the relationship between the AO and

the vendor/consultant is considered important

(Dittrich et al., 2009; Sammon and Adam, 2002).

We found evidence of unevenly divided power

between these organizations that hindered the

development. One party with the upper hand in

decision-making is capable of steering the project in

biased way. In addition to the AO-vendor

relationship in the network, third parties can

establish important relationships between

themselves, and hence complicate the network

structure and power relationships. Both these issues

are challenging for the overall management of the

network, yet neither of them was earlier identified in

the literature.

Inter-organizational relationships define the

development model for the EDN, which was

identified as a source of pain. Nevertheless, the

current literature does not clearly separate the AO

and the vendor when discussing ERP software

development and product management challenges.

We see that when developing the system in a

network, a joint development model is very

important in order to avoid the misalignment of

business and IT in all organizations, for example.

Conflicting Objectives. Since EDNs reach over

organizational and national boundaries, and

stakeholders may have differing goals, multi-site

issues such as cultural differences hampers the

overall project (Momoh et al., 2010). Problems arise

from the conflicting agendas and objectives between

different functional units within the AO (Amid et al.,

2012). In addition, our study highlighted the dual

objective of the vendor that hinders the

development. The vendor’s custom versus product

dilemma caused significant problems. For example,

mutual understanding was difficult to build or the

resources for development were insufficient. Similar

project management challenges from the AO’s point

of view have been identified (Kim et al., 2005;

Shirouyehzad et al., 2011) but these do not usually

take the vendor into account.

The sheer number of stakeholders involved in

ERP projects has been considered challenging

(Momoh et al., 2010). Sammon and Adam (2002)

stress the need to understand the relationships

between the organizations involved in ERP

development. Current literature is not fully aware of

these relationships and their impact on the ERP

development. Our study takes a step forward in

filling this gap by observing that in all cases both the

third parties and the organizations’ separate

stakeholders can have a huge impact on the ERP

project.

This study has its limitations. First, the results of

qualitative case studies are not easily generalizable,

so quantitative studies on EDNs would also be

useful. Second, the context should not be dismissed

when applying these findings. These networks are

all from similar cultural environments that are in

general considered to be democratic in terms of

coordination. Within and between the organizations,

more emphasis is laid on trust than on different legal

agreements. Hence, these findings, as such, may not

be applicable, for example, in North American

organizations. Third, all cases are from a custom

system development context that differs from

customization of an off-the-shelf product

(Damsgaard and Karlsbjerg, 2010), e.g. the role of

the vendor organization is not the same. However,

Chiasson and Green (2007) suggest that: “the

differences between packaged software and

customized development are one of degree, not kind”

(p. 553). Thus, we believe our findings are also

usable for packaged EDN.

In future, we want to understand how the

identified pain could be avoided. For example, how

can the issues caused by different development

models be overcome. Investigating the suitability of

agile methods in such environments would be a

potential area for future research. Communication

between different groups in ERP projects is

challenging (Al-Mashari et al., 2003). Thus, the

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

264

EDNs should be studied more deeply, and especially

how the EDN forms the development model and

how information is shared between the EDN.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study contributes to field of ERP and IS

research. The objective of this paper was to identify

those challenges that may hinder ERP development

when co-operating in multiple stakeholder networks.

These challenges were uncovered by analyzing 43

interviews from the EDNs of three large

organizations. The findings were classified into three

main categories: evolving network, inter-

organizational issues, and conflicting objectives.

These were further divided into 11 sub-categories.

The aim of this paper was not to provide yet

another set of critical failure factors. In relation to

the literature, however, we found that four of the

identified challenges were only partly covered

earlier and three of the challenges had not gotten any

attention before. The novel issues hindering the ERP

development activities were temporal involvement

of organizations, unevenly divided power between

stakeholders, and dual objectives of the vendor.

This study took an important step to treat ERP

development and its challenges from a network

perspective. For practitioners, the categories provide

a tool to evaluate and seek possible causes of

problems in such networks. By doing so,

organizations could be able to focus more on the

relevant issues in ERP development, and thus

improve the overall management of the project. The

categorization is not only useful for the AO but may

be used by other stakeholders in the network as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the Academy of Finland

grants #259267, #259831 and #259454.

REFERENCES

Al-Mashari, M., Al-Mudimigh, A. & Zairi, M. 2003,

"Enterprise resource planning: a taxonomy of critical

factors", Eur. J. Oper. Res., vol. 146(2), pp. 352-364.

Amid, A., Moalagh, M. & Zare Ravasan, A. 2012,

"Identification and classification of ERP critical

failure factors in Iranian industries", Inf Syst, vol.

37(3), pp. 227-237.

Barker, T. & Frolick, M.N. 2003, "ERP implementation

failure: A case study", Inf. Syst. Manage., vol. 20(4),

pp. 43-49.

Berente, N., Yoo, Y. & Lyytinen, K. 2008, "Alignment or

drift? Loose coupling over time in NASA's ERP

implementation", ICIS 2008 Proceedings. Paper 180.

Chiasson, M.W. & Green, L. 2007, "Questioning the IT

artefact: user practices that can, could, and cannot be

supported in packaged-software designs", European

Journal of Information Systems, vol. 16(5), pp. 542-

554.

CIO. 2009. “10 Famous ERP Disasters, Dustups and

Disappointments”.http://www.cio.com/article/486284/

10_Famous_ERP_Disasters_Dustups_and_Disappoint

ments (accessed November 5th 2013).

Damsgaard, J. & Karlsbjerg, J. 2010, "Seven principles for

selecting software packages", Communications of the

ACM, vol. 53(8), pp. 63-71.

Davenport, T.H. 1998, "Putting the enterprise into the

enterprise system", Harv. Bus. Rev., vol. 76(4).

Dezdar, S. & Sulaiman, A. 2009, "Successful enterprise

resource planning implementation: taxonomy of

critical factors", Industrial Management & Data

Systems, vol. 109(8), pp. 1037-1052.

Dittrich, Y., Vaucouleur, S. & Giff, S. 2009, "ERP

customization as software engineering: knowledge

sharing and cooperation", Software, IEEE, vol. 26(6),

pp. 41-47.

Ernst, D. 2010, "Upgrading through innovation in a small

network economy: insights from Taiwan's IT

industry", Economics of Innovation and New

Technology, vol. 19(4), pp. 295-324.

Ernst, D. & Kim, L. 2002, "Global production networks,

knowledge diffusion, and local capability formation",

Research policy, vol. 31(8), pp. 1417-1429.

Hong, K. & Kim, Y. 2002, "The critical success factors for

ERP implementation: an organizational fit

perspective", Information & Management, vol. 40(1),

pp. 25-40.

Isomäki, H. & Pekkola, S. 2011, Reframing Humans in

Information Systems Development, Springer.

Kim, Y., Lee, Z. & Gosain, S. 2005, "Impediments to

successful ERP implementation process", Business

Process Management Journal, vol. 11(2), pp. 158-170.

Momoh, A., Roy, R. & Shehab, E. 2010, "Challenges in

enterprise resource planning implementation: state-of-

the-art", Business Process Management Journal, vol.

16(4), pp. 537-565.

Nah, F.F., Lau, J.L. & Kuang, J. 2001, "Critical factors for

successful implementation of enterprise systems",

Business process management journal, vol. 7(3), pp.

285-296.

Nour, M. A. & Mouakket, S. 2011. "A classification

framework of critical success factors for erp systems

implementation: a multi-stakeholder perspective,"

International Journal of Enterprise Information

Systems, vol. 7, pp. 56-71.

Pekkola, S., Niemi, E., Rossi, M., Ruskamo, M. & and

Salmimaa, T. 2013, "ERP Research At ECIS And

ICIS: A Fashion Wave Calming Down?", ECIS, .

Sammon, D. & Adam, F. 2002, "Decision Making In The

NetworksofPaininERPDevelopment

265

ERP Community.", ECIS, p. 1005-1013.

Sarker, S. & Lee, A.S. 2003, "Using a case study to test

the role of three key social enablers in ERP

implementation", Information & Management, vol.

40(8), pp. 813-829.

Sarker, S., Sarker, S., Sahaym, A. & Bjørn-Andersen, N.

2012, "Exploring value cocreation in relationships

between an ERP vendor and its partners: a revelatory

case study", MIS Quarterly, vol. 36(1), pp. 317-338.

Schlichter, B.R. & Kraemmergaard, P. 2010, "A

comprehensive literature review of the ERP research

field over a decade", Journal of Enterprise Information

Management, vol. 23(4), pp. 486-520.

Shirouyehzad, H., Dabestani, R. & Badakhshian, M. 2011,

"The FMEA Approach to Identification of Critical

Failure Factors in ERP Implementation", International

Business Research, vol. 4(3), pp. p254.

Walsham, G. 1995. “Interpretive case studies in IS

research: nature and method”, EJIS, 4, pp. 74-81.

Webster, J. & Watson, R.T. 2002, "Analyzing the Past to

Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review",

MIS quarterly, vol. 26(2).

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

266