Scoping Customer Relationship Management Strategy in HEI

Understanding Steps towards Alignment of Customer and Management Needs

B. Khashab, S.R. Gulliver, A. Alsoud and M. Kyritsis

School of Business Informatics, Systems and Accounting, University of Reading (UK), Henley Business School,

RG6 6UR, Reading, Berkshire, U.K.

Keywords: Customer Relationship Management (CRM), Strategy, Scoping; Alignment, Higher Education Institutions.

Abstract: Higher Education Institutions (HEI) are complex organisations, offering a wide range of services, which

involve a multiplicity of customers, stakeholders and service providers; both in terms of type and number.

Satisfying a diverse set of customer groups is complex, and requires development of strategic Customer

Relationship Management (CRM). This paper contributes to the HEI area, by proposing an approach that

scopes CRM strategy, allowing us a better understanding CRM implementation in Higher Education

Institutions; maximising alignment of customer and management desires, expectation and needs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) means

different things to different people, however, despite

confused and often conflicting understandings,

interest in CRM implementation within Higher

Education Institutions (HEIs) has soared. There is

increasing evidence that CRM should be managed as

a critical business strategy (e.g. Lindgreen et al,

2006; Rigby and Ledingham, 2004), which is of

strategic imperative to business success (Bohling et

al., 2006). There is, however, no consensus or

developed methods demonstrating how customer

desires expectations and needs (DEN), and business

strategy can be systematically aligned.

By identifying customers, the effective scope of

their needs can by defined. By identifying

appropriate steps in HEI CRM strategy development

can support the creation of superior value to

customers. In this paper we aim to better understand

existing CRM implementation in HEI. Presentation

of materials in this study is as follows: In section 2

we present a literature review that highlights existing

discrepancies in CRM implementation. This is

followed, in section 3, by a brief explanation of

related work concerning CRM, with focus on the

HEI setting. We discuss the research methods

adopted in section 4, and as a result of practitioner

interviews, in sections 5 and 6 we propose a six-step

approach, to scope strategy and maximise alignment

of customer and management desire, expectations

and needs.

2 CRM DISCREPANCY

To date there has been some confusion, in both

commerce and academia, concerning “what CRM

is”. CRM can be conceptualised as a strategy,

process, capability, philosophy or technological

solution (Zablah, et al., 2004), which has lead to

some significant differences in the perception of

what CRM includes. Lindgreen et al. (2006), for

example, claims that CRM can be grouped into three

main themes (strategic, infrastructure and process).

Poornima and Charantimath (2011), Buttle (2009)

and Thakur et al. (2006) all consider CRM as a core

business strategy, which maximises revenue,

profitability, and customer satisfaction; and openly

reject the perspective that CRM is nothing other than

a technical solution (Payne and Frow, 2005). CRM

in this study, and in the context of HEI, is defined as

a cross-departmental, customer-centred, technology-

aggregated business-process-management strategy

that should optimise customer relationships; and

yield benefits that span the entire enterprise

(Goldenberg, 2000).

Due to the historically high rate of CRM

implementation failure, and because of the lack of

understanding concerning the scope of CRM, a

267

Khashab B., R. Gulliver S., Alsoud A. and Kyritsis M..

Scoping Customer Relationship Management Strategy in HEI - Understanding Steps towards Alignment of Customer and Management Needs.

DOI: 10.5220/0004891002670274

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 267-274

ISBN: 978-989-758-028-4

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

number of CRM implementation frameworks have

been developed to support practitioners. Gartner

(2001) introduced a CRM model called ‘The Eight

Building Blocks of CRM’, which considers eight

steps towards success (Radcliffe, 2001), which

specifically emphasised the need to focus on the

strategic role of CRM. Payne and Frow (2005)

proposed a strategic CRM framework that

underscored the importance of strategy as the

starting point, in order to overcome the shortfall of

considering CRM as simply a narrow technological

solution. Payne and Frow (2005) state that business

strategy and customer strategy alignment affects

CRM strategy success. They stress a need to

consider business strategy at the starting point to

define how the customer strategy should evolve.

Thakur et al. (2006) identified seven steps to

implementing CRM strategy (i.e. make customers

the essential focus of CRM strategy; categorise

customers on the basis of their perceived

importance; deliver value to prioritised customers;

concentrate on strategic capabilities; create strategies

that are customer centric; select CRM technology;

and implement the CRM strategy). Finally Buttle

(2009) defined a five phase implementation

framework, which focused on the development of

CRM strategy as being key to CRM implementation

success. Buttle (2009) defined CRM strategy as “a

high-level plan of action that aligns people,

processes and technology to achieve customer-

related goals.” In his strategy stage, he highlighted

the significance of establishing the goals based on

the prioritised and focused business processes.

Buttle argued that strategic CRM is a main

customer-centric business strategy that concentrates

on spreading customer oriented business culture.

To be effective, as identified by all key CRM

implementation frameworks, a CRM strategy must

be effectively aligned to the business strategy (Payne

and Frow, 2005). However, as

customer/management desires, expectation and

needs differ (Anton, 1996), it is important to

understand and manage the conflict that occurs

(Kotorov, 2002).

3 RELATED WORK IN HEI

Higher Education Institutions (HEI) are complex

organisations, offering a wide range of services (i.e.

teaching, research, knowledge transfer), involving a

multiplicity of stakeholders; both in terms of type

and numbers. Moreover, customer types vary

significantly (e.g. prospective / current students,

parents, alumni, business community, accreditation

organisations, government funding agencies, etc.).

Unlike most companies, however the output product

in HEI is commonly the customer, i.e. a student

(Kotler and Fox, 1985). Satisfying the conflicting

needs of diverse customer groups and stakeholders is

complex.

Daradoumis et al. (2010) highlighted that only

limited studies have considered CRM in the domain

of HEIs; and that existing studies commonly only

consider a limited scope or context within HEI

activity (e.g. prospective student activity); which has

resulted in solutions that do not consider all CRM

solution types (i.e. strategic, analytical, operational

and collaborative) (Buttle, 2009).

Seeman and O’Hara (2006), found that

implementing CRM systems within the university

improves management of customer data process,

raises student oriented focus, and increases student

retention, loyalty and satisfaction with the

university’s educational programs and services.

Seeman and O’Hara suggested that treating students

as customers enables HEIs to gain a competitive

advantage; improving capabilities to attract, keep

and satisfy its customers via superior value.

Moreover, Biczysko (2010) stated that CRM

systems can identify students who might drop out.

Biczysko claimed that by conducting frequent

surveys to measure the student’s satisfaction, and

reacting immediately to their demands, student

retention has been improved; which is of significant

financial value to management.

With increasing international competition within

the HEI sector, there is increasing pressure to satisfy

‘customer’ needs, yet limited support is given within

this complex sector to CRM strategy development.

Our research aims to understand effective CRM

implementation in HEIs, by studying existing HEI

CRM implementation. This is then used to develop

an approach, which can provide insights to

institutions that are planning adoption of a CRM

solution.

4 RESEARCH METHOD

To better understand CRM implementation in HEI,

and thus enable us to define a CRM strategy

development approach, we conducted interviews

with individuals who had in-depth experience of

CRM implementation in a range of UK based

universities. By tapping into the knowledge of

experienced implementers, we sought to gain an in-

depth understanding of CRM HEI implementation

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

268

success and failure. The research aimed to achieve

two primary objectives: i) To investigate the extent

to which HIEs employ CRM strategies, if any, and

how these are formulated; ii) To highlight key areas

that appear critical to the success of CRM

implementation in HEIs.

Universities selected for this study had CRM

implementation experience, and the people

interviewed were selected from Joint Information

Systems Committee (JISC) reports; which feature

more than 27 UK institutions websites. Ten semi-

structured interviews were carried out with key

implementation stakeholders (including one vice

chancellor, four project managers, two IT managers,

and three CRM managers) taken from six different

universities. Data was analysed using the Content

Analysis Method (Babbie, 2010), which facilitates

analysis and interpretation through the use of

structured codes on the basis of the following

questions: 1) Did they have a clear CRM strategy?

2) How did they formulate this strategy? 3) What are

the critical success factors that affected CRM

implementation? 4) How did they define the key

stakeholders involved in the CRM implementation?

5) What method did they use to define the

stakeholders? The process led to the emergence of

six critical steps, justified and elaborated in sections

5 and 6 respectively, which need to be addressed to

achieve successful HEI CRM strategic scoping and

alignment.

5 APPROACH DEFINITION

Interview data revealed a need to include six key

steps, which are: i) Define the CRM output focus; ii)

Define relevant customer groups; iii) Contextualise

output; iv) Map output lifecycle; v) Define customer

group needs/expectation/desires; vi) Quantify and

evaluate needs/expectation/desires in context of the

business strategy.

5.1 Step 1 - Define CRM Focal Output

70 % of interviewees stated that top management

should initiate CRM strategy; and that Customer

Relationship Management strategy should align with

the business strategy. “We look at our strategic

objectives as a university” (Interviewee 4).

Interviewees pointed out that it is essential to have

“a very detailed understanding of what the corporate

business requirements are, and how that might relate

to the wide strategy” (Interviewee 7). Interestingly,

one of the key factors, identified by 70% of

respondents, was the need to have “a different

strategy for different sectors and customer groups”

(i.e. specific teaching, research, knowledge transfer

outputs, degree level, etc.). Accordingly, to achieve

implementation success, each CRM strategy should

have a clear focus. In our approach we propose an

initial step that defines the HEI output scope.

5.2 Step 2 - Define Customer Groups

If separate CRM strategies are defined for specific

HEI output, it is important to define what customer

groups relate to that output. 60% of respondents

indicated that CRM strategy can only be gained by

understanding the bottom line (i.e. stakeholder

needs). It is therefore critical to define the primary

client(s), yet highlight the interaction of additional

secondary beneficiaries, e.g. staff who would not be

employed if the output did not exist. A step was

therefore added to our approach that defined all

customer groups (both primary and secondary),

highlighting their role in context of the focal output.

5.3 Step 3 - Contextualise Output

“Most of the goals for CRM systems will be driven

by the particular function” (Interviewee 5). Thus

CRM strategy should be designed around the

strategic functional needs of a specific output focus.

To deliver target functionality for specific customer

groups, in context of the focal output, it is important

that process occurs change at the appropriate point

within the organisation. “You have got to understand

the overall business processes that you’re trying to

satisfy” (interviewee 4). Accordingly it is important

to add a step to our approach that scoped the impact

of the CRM strategy in context of organisational

outputs, i.e. does change need to occur at University,

Faculty or School level; thus also highlighting the

scope of influence held by different customer groups

on the specific focal output.

5.4 Step 4 – Lifecycle Mapping

“It is important not to disregard the output lifecycle

when implementing CRM” (Interviewee 3). To

understand how customer groups interact with, and

influence, the focal output, it is important to

understand the lifecycle of contact points (i.e.

processes, activities, events and roles) in context of

the focal output. Respondent 6 mentioned that

different product customer groups need different

solutions at different times. “The undergraduate

experience is very different to the PG experience”

ScopingCustomerRelationshipManagementStrategyinHEI-UnderstandingStepstowardsAlignmentofCustomerand

ManagementNeeds

269

(Interviewee 6); and hence it is important, when

defining the CRM strategy, that the ‘as is’ lifecycle

for the focal output is clearly defined. Accordingly,

a step was added to our approach to map ‘as-is’

activities, events and roles involved in the lifecycle

of the focal output.

5.5 Step 5 - Defining DEN

60% of interviewees agreed that it is critically

important to consider students’ needs and

expectations when creating strategic CRM goals.

70% of the respondents highlighted the importance

of considering student experience as a pre-

implementation requirement. “I don’t think you can

really set out objectives without taking into account

what the students want” (Interviewee 10).

Accordingly a step was added to our approach,

which captured customer group desires, expectations

and needs (DEN).

5.6 Step 6 - Quantify and evaluate DEN

Capturing customer DEN in HEI is substantial to the

development of a successful CRM strategy; however

customer DEN (bottom up) needs to be balanced

against company objectives (top-down). Simply

capturing customer DEN does not fully consider

issues of practical alignment with the business

strategy. Accordingly, a step is needed in our

approach where senior management consider

customer DEN (bottom-up), and identify i) which

DEN will be taken forward, and ii) what quantifiable

measurement should be assigned.

6 SCOPING METHOD

6.1 Define CRM Focal Output

The first step of our approach is to identify the

university’s high level CRM strategic output focus,

i.e. the university output where value needs to be

added to the customer interaction. As HEI produce

multiple outputs (Hashimoto and Cohn, 1997),

defining the scope for the CRM strategy is critical to

successful resource use and implementation. Top

HEI management (i.e. at University level) are

therefore required to strategically prioritise what

outputs are critical to the University.

The HEI should focus CRM strategy

development on or around specific outputs, i.e. to

allow top HEI management highlighting what

discernable outcomes will be positively affected by

the specific CRM strategy. The focal output should

therefore be an output that senior management are

interested in strategically improving. If multiple

focal outputs are identified by management, then

distinct CRM strategies should be created to

consider each output. By focusing on outputs we are

able to determine the level and scope of

implementation within the organisation. By

following this first step, senior HEI management

will be able to discuss what business outcomes need

to be develop; via implementation of CRM systems.

By allowing senior HEI staff to define the high-level

focus of the CRM strategy, benefits can be justified,

the same senior management will also be ready,

willing, and able to fund / support resulting CRM

projects and solution implementations. In this paper

the focal output, used in the example will be the full-

time MBA degrees in a business school.

6.2 Define Customer Groups

Numerous studies have described the significant

importance of segmentation on the successful

implementation of a CRM strategy (e.g. Bligh and

Turk, 2004; Rigby et al., 2002). There are numerous

stakeholders within the context of any HEI output.

Spanbauer (1995) grouped HEI customers into two

categories: external (employers, students,

community, government, etc.) and internal

(instructors, service department staff, etc.). Each

stakeholder, in the lifecycle of the focal output, will

influence and/or benefit from the output - either

directly, as the client, or indirectly via allocation of

resource. By simply using a single one-umbrella

classification, it is impossible to identify the

complexity of HE stakeholder influence.

Accordingly, in the second step of our approach

we propose the use of stakeholder capture and

categorisation methods (as defined in Liu et al.,

2007); which applies organisational semiotic

approaches to classify the role and influence of

different stakeholders benefiting from the output.

Six role categories, defined in Liu et al. (2007), are:

1) Actors, i.e. those that take action that directly

influences the outcome; 2) Clients, who receive the

consequences of the outcomes; 3) Providers, who

provide the conditions to facilitate the deliverables

of the outcome; 4) Facilitators, who are the initiators

and enablers of an output, and are the ones who

solve conflicts and ensure continuity and steer the

team towards its goals; 5) Governing Bodies, who

take part in the project planning and management

planning and supply the legal framework; and 6)

Bystanders, who are not part of the project but can

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

270

influence the outcome. Staff involved in the

provision of the focal output (at faculty / school

level), should define how all stakeholders’ influence,

and benefit from, the delivery of the defined focal

output; with each segment classified as a separate

customer group. This allocation of roles allows us to

define direct and indirect customer groups (i.e.

beneficiaries of the given output), and the roles that

they take in the focal output lifecycle. In the context

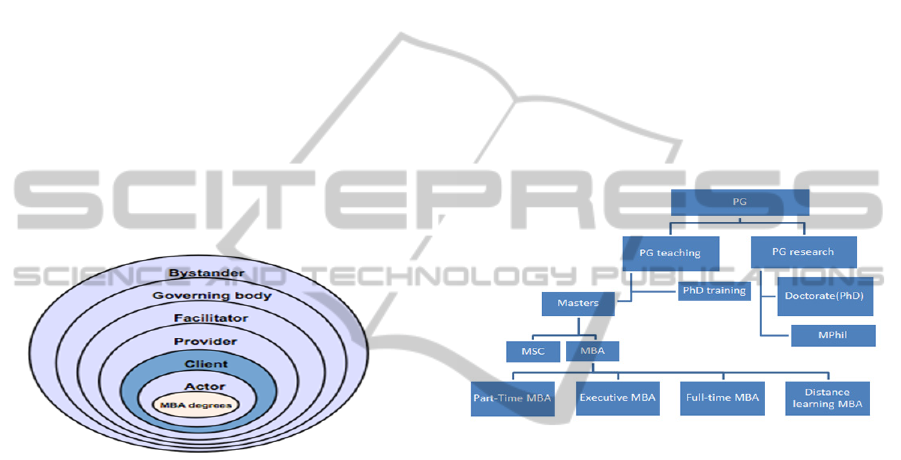

of an MBA programme output (see Figure 1),

stakeholders might be: Actor - programme director;

Client - MBA students, supporting companies;

Provider - financial departments, teaching staff,

module conveners; Facilitator – Research

supervisors, admissions; Governing body –

University senate; Bystander: business

organisations, community institutions, press

agencies, etc. The list of customer groups should

categorise all stakeholders involved in the lifecycle

of the focal output.

Figure 1: CRM roles influencing HEI output.

The results from this step should be tabulated

separately for each focal output. This table should

also be, as required, augmented with information

concerning stakeholder responsibilities, roles, and

job function.

6.3 Contextualise Output

Renner (2000) stated that maximising customer

relationships requires a full understanding of their

scope. To understand the size of our focal output

within the organisation, and the scope of customer

group relationships, the third step of our approach

maps all customer groups (see section 5.2) in context

of the focus output hierarchy. Figure 2 shows a

simplified HEI hierarchical structure for

postgraduate degrees. If senior management defines

‘MBA’ as the HEI CRM ‘focal output’ (see step 1),

it is important to note that the MBA is just one of

many masters programmes. The MBA is by

definition a master programme, yet if MBA

specifically is deemed by management as deserving

an augmented level of customer service / interaction,

the CRM strategy should not necessarily impact all

master programmes; but at the sub-level of MBA

specifically. By scoping the influence of the focus

output we are able to define the scope of the CRM

strategy. In our example, the MBA programme is

sub-categorised as being full-time, part-time,

executive, or via distance learning. Each of these

delivery modes may have a very different model of

customer relationship. As we are considering just the

full-time MBA it is important to define whether all

delivery modes are considered to be included in the

scope of a single strategy (i.e. one strategy that will

apply to all four cohorts), or whether different

teaching modes equates to four separate focal

outputs (with potentially separate CRM strategies

required for each).

Figure 2: Hierarchical structure for postgraduate degrees

to facilitate contextualisation.

Defining the scope of the focal object, in context of

the organisation, allows implementation staff to

support senior staff to better tailor the strategy

definition. Moreover, identifying smaller and

smaller groups enables the university to better

manage the use of business processes/services with

each segment; treating customers in accordance to

their values and needs.

6.4 Lifecycle Mapping

The fourth step in our approach relates to the

detailed mapping of all customer groups, to current

Processes, Activities, Events and Roles (PAER) in

the lifecycle of the output (AS IS) – i.e. its current

state. O'Rand and Krecker (1990) claimed that

consideration and use of life cycles and life-events

supports alignment of desperate viewpoints

concerning a single entity or person. Unsurprisingly,

the life event concept is being increasingly adopted,

by public information service providers, to manage

customer experience (Kavadias and Tambouris,

ScopingCustomerRelationshipManagementStrategyinHEI-UnderstandingStepstowardsAlignmentofCustomerand

ManagementNeeds

271

2003). The use of focal object, lifecycle and life-

events, allows us to consider the ordering and impact

of customer group interaction. Since, within HEI,

different stakeholders (i.e. customer groups), interact

with, influence and/or benefit from the focal object

at different points in the output lifecycle, it is

important that information about the focal output

lifecycle should be used to structure the relationships

of customer groups in context of time.

As the primary client passes through the

lifecycle of the output (e.g. Full time MBA students

in our example), customer groups will have varying

influence / interaction on specific Processes,

Activities, Events and Roles (PAER) at each life

stage (e.g. recruitment stage). By understanding the

layout of these PAER, in context of the output

lifecycle, the experience of all customer groups can

be understood incrementally; thus building up an

interaction model of the whole focal output.

Such a model will help the university determine

the customer experience at each stage of the

lifecycle; thus highlighting areas that require

improvement / development. For instance, within the

MBA recruitment stage, measuring applicant

experience can help HEI admissions staff to guide

students to the correct programme (full-time/part-

time/executive); and can be used to define any areas

where better resourced is required.

6.5 Defining DEN

Desires, expectations and needs (DEN) are

differentiated by a set of subtle definitions

(Boradkar, 2010). Needs equate to essential

functional requirements, and must be met to ensure

that the focal output is viable. Expectations are

benefits, attributes and / or outcomes that

customer groups expect to exist in the focal output.

If an expectation is not delivered in the final output,

then the customer would, if left unmanaged, suffer a

feeling of disappointment; from which a feeling of

discontentment will result (Kano, 1995). Galbreath

and Rogers (1999) argued that a business cannot

survive if they do not meet their customer needs and

expectations. Desires are attributes and / or

outcomes that customer groups would like to exist in

the focal output, however customers are unlikely to

expect all desires to be met.

In HEIs, different stakeholders, e.g. a student and

the HEI vice chancellor, will have a very different

perspective on essential DENs. For example, in the

context of MBA taught programmes, a student is

both the client (i.e. the primary customer), but

arguably also the output. The student is paying to

experience the output lifecycle, yet course content is

developed by academic staff to often align with the

wider school teaching portfolio. Accordingly senior

management risk prioritising DEN that are of little,

or no significant importance to the paying client.

Explicit classification of desires, expectation and

needs, particularly from client and management

perspectives, is important to consider both bottom-

up (from client) and top-down (management)

desperate views.

We propose that in the fifth step of our approach,

four sub-steps are required. Firstly the focal output

(i.e. Full-Time MBA) DEN of senior management

should be collected and considered against the ‘AS-

IS’ lifecycle, defined in section 6.4. Secondly, senior

management should use a Likert type scale,

prioritise their DEN; in the paper we will call this A.

Thirdly customer groups (i.e. relating to full-time

MBA) should be asked to assess management DENs

from their own perspectives; using a similar Likert

type scale; in the paper we will call this B. The

result can be used to highlight the proposed CRM

improvements that will most positively impact

specific customer groups. Finally, we suggest that

customer groups define a set of additional DEN

concerning the focal object; and a weight (on a

Likert type scale) to identify their perception of

importance.

Figure 3: Customer / Management DEN definition.

6.6 Quantify and evaluate DEN

Porter (2010) stated that HEI institutions should

focus on the realistic objectives. Management should

evaluate which DEN should determine the final set

of focal object DEN (see figure 3). As a result of

customer feedback, a final set of DEN should be

evaluated. It can be argued that the more the HEI

knows about its customer groups, and allocates

available resources effectively to achieve their DEN,

the greater management can enhance business

performance and improve customer satisfaction

(Kirkby, 2002); which in turn leads to customer

loyalty (Anderson and Mittal, 2000). Whilst top

managers are ultimately responsible for formulating

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

272

and defining the final CRM strategy, feedback and

customer DEN (highlighted in section 6.5), however

for the sake of customer acceptance, senior

managers should consider customer DEN /

feedback; particularly in context of the focal output

lifecycle. If senior managers disregard customer

DENs, and do not view them as being critical, then

they risk loosing customer satisfaction. If, however,

management implement customer DEN, without

consideration of business strategy, they risk

inclusion of DEN that may not ultimately be viable.

Accordingly HEIs need to balance management

(top-down) and end-customer (bottom-up) DEN.

If numeric quantification is needed, gap analysis

can be used to allow the analyst to gauge customer

attitudes towards a given strategy (whether positive

or negative). For example, in their SERVQUAL

model, Parasuraman et al. (1988) stresses on the

importance of measuring, understanding customer

expectations, and aligning them to the business

processes. Closing expectation gaps between the

perceived service and expected services allowing to

align customer strategy with the business strategies

and services.

To identify and prioritise customer expectation

gaps, we suggest adopting an adapted version of

Cheng et al.’s (1998) gap analysis method. Value =

(A-B)*A; where A is the management strategic

score, and B is the defined customer relevance score.

If the customer score is less than the management

score, the value will be positive; implying that the

specific DEN is more important to management than

the customer group. If the customer score is more

than the management score, then the value will be

negative; implying that a DEN is more important to

the customer than management. To reflect the

strategic importance of the specific DEN value, we

magnify the sum by the management strategic score.

The greater the level of importance placed on the

DEN by management, the larger the final value.

The goal of this step is to view the entire

spectrum of DENs, and decide which to consider

and which to ignore. Such information facilitates

senior management to focus on the key DEN that

supports the business strategy that will be accepted

positively by customers. A wide gap between

management and customer requirements indicates an

absence of alignment. Where value is deemed to be

negative, the viability of client DENs must be

assessed by senior managers.

In the case of our full-time MBA focal object,

students might expect regular networking with

alumni students. Management might have given this

service a priority of 3 (i.e. A) on a 7 point Likert

style scale. If MBA students, however, give this

service a priority of 7 (i.e. B) on a similar 7 point

Likert style scale, the service value is currently (-

12); Value = (A-B)*A. As this is a negative number

management can instantly see that a low focus on

this service risks resulting in dissatisfaction from

students. It is then up to management to decide

whether resource can be viably invested.

Gap analysis quantifies the importance of DEN,

and allows managers to assess the plausibility of

each set of DENs; i.e. decide which should be

carried forward strategically. Moreover, gap analysis

supports quantification of each DEN, allowing

management to quantify CRM outcome.

The scoping strategy that we propose seeks to

align business model imperatives with customer

DENs, and to check the appropriateness of the

strategy as a tool for prioritising, segmenting, and

quantifying DENs, as a result of ranking and

mutually defined priorities. If customer and senior

management DENs are aligned, then the strategy

adopted will ideally implement strategically

important DEN, whilst providing customers with

what they want.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In a complex organisation, such as the HEIs, in

which multiple stakeholders have very different sets

of needs, expectations, and desires, the challenge of

implementing CRM solutions becomes particularly

great. In this paper, we develop a scoping approach

to help align the CRM strategy of management with

the desire, expectation and needs of customer

groups. Our method builds upon practical evidence

from the results obtained with interviews, which

were systematically synthesised. We investigated

HEI CRM implementation issues, placing focus on

institutions that have implemented CRM, with the

aim of understanding effective steps in the

development of HEI CRM strategy. Focusing on and

understanding customer groups’ desires,

expectations and needs can be used to support

effective strategy creation; which in turn, improves a

HEIs unique position.

It is believed that this paper is of significant

value to both CRM researches and practitioners;

when developing and implementing CRM strategies

within HEIs. Future research will focus on the

iterative implementation of our CRM strategy-

scoping approach; to help us identify the pros and

cons of the proposed approach in maximising the

alignment of customer and management DEN.

ScopingCustomerRelationshipManagementStrategyinHEI-UnderstandingStepstowardsAlignmentofCustomerand

ManagementNeeds

273

REFERENCES

Anderson, E. W. and Mittal, V., 2000. Strengthening the

Satisfaction-Profit Chain. Journal of Service Research,

Volume 3, No. 2, pp.107-120.

Anton, J. 1996. Customer Relationship Management:

Making Hard Decision with Soft Number, Prentice

Hall, Englewood Cliffs, and New Jersey.

Babbie, E., 2010. The Practice of Social Research (12th

Ed.). Wadsworth: Cengage Learning. p. 530.

Biczysko, D., 2010. CRM solutions for Education. In: P.

Jałowiecki and A. Orłowski, ed. 2010. Information

systems in management, Distant Learning and Web

Solutions for Education and Business. WULS Press,

Warsaw, 1st edition, pp.18-29.

Bligh, P. and Turk, D., 2004. CRM Unplugged Releasing

CRM’s Strategic Value. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Bohling, T., et al., 2006. CRM Implementation

Effectiveness Issues and Insights." Journal of Service

Research 9(2), 184-194.

Boradkar, P. 2010. Designing things: a critical

introduction to the culture of objects, Berg.163-164.

Buttle, F. 2009. Customer Relationship Management

(Paperback). 2nd Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann.

Cheng, B. W. and Lin, S. P. and Liu, J. C., 1998. Applying

quality function deployment to improve the total

service quality in a Hospital’s Out-patient Department,

Proceedings of National Science Council: Humanities

& Social Science, 8(3), 479–493.

Daradoumis, T. et al. 2010. CRM Applied to Higher

Education: Developing an e-Monitoring System to

Improve Relationships in e-Learning Environments.

International Journal of Services Technology and

Management, Volume 14, Issue 1, 103-125.

Galbreath, J. and T. Rogers. 1999. Customer relationship

leadership: a leadership and motivation model for the

twenty-first century business. The TQM magazine

11(3), 161-171.

Goldenberg, B. 2000. What is CRM? What is an e-

customer? Why you need them now, in Proceedings of

DCI Customer Relationship Management Conference,

Boston, MA.

Hashimoto, K. and Cohn, E. 1997. Economies of scale and

scope in Japanese private universities. Education

Economics 5(2), 107-115.

Kano N. 1995. Upsizing the organization by attractive

quality creation G.H. Kanji, Total Quality

Management: Proceedings of the First World

Congress. Chapman.

Kavadias, G., Tambouris, E. 2003. GovML: A Markup

Language for Describing Public Services and Life

Events, in Proceedings of the 4th IFIP international

working conference on Knowledge management in

electronic government, 106-115.

Kotler, P., and Fox, K. 1985. Strategic Marketing for

Educational Institutions. Prentice Hall. New Jersey.

Kotorov, R. P. 2002. Ubiquitous organization:

organizational design for e-CRM. Business Process

Management Journal 8(3), 218-232.

Lindgreen, A., Palmer, R., Vanhamme, J., and Wouters, J.

2006. A relationship management assessment tool:

Questioning, identifying, and prioritizing critical

aspects of customer relationships. Industrial

Marketing Management, 35(1), 57−71.

Liu, K and Sun, L and Tan, S. 2007. Using Problem

Articulation Method to Assist Planning and

Management of Complex projects, in Charrel, P. J and

Galarreta, D. (Eds.) Project Management and Risk

Management in Complex Projects: Studies in

Organisational Semiotics. Springer, Netherlands, 1-14.

O'Rand M and Krecker L. 1990. Concepts of the life

cycle: their history, meanings and is- sues in the social

sciences. Annual review of sociology. Vol. 16, 241-62

Parasuraman, A. Zeithaml, V.A, and Berry, L.L. 1998.

SERVQUAL: a multi-item scale for measuring

consumer perceptions of service quality, Journal of

Retailing Vol. 64.12-40.

Radcliffe, J. 2001. Eight Building Blocks of CRM: A

Framework for Success. Gartner research note.

Renner, D. 2000. Customer relationship management: a

new weapon in your competitive arsenal”, Siebel

Magazine, Vol. 1 No. 2.

Payne, A. and Frow, P. 2005. A strategic framework for

customer relationship management. Journal of

Marketing, Vol. 69, 167-76.

Poornima M. C and Charantimath, M. P. 2011. Total

Quality Management, Pearson Education India, 477-

480.

Porter, B. 2010. KRADLE Project Kingston Relationship

Application Data for Learner Engagement. [Online].

Available at: http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/

programmes/bce/kradlefinalreport.pdf. [Accessed:

12th November, 2013]

Kirkby, J. (2002). Developing a CRM Vision and

Strategy. GartnerG2, A1, CRM31.

Rigby. D and Ledingham, D. 2004, CRM done right",

Harvard Business Review, 11.

Rigby, D. K., et al. 2002. Avoid the four perils of CRM."

Harvard Business Review 80(2), 101-109.

Seeman, D.E. and O'Hara, M., 2006. Customer

relationship management in higher education: Using

information systems to improve the student-school

relationship, Campus - Wide Information Systems,

Vol.23.No 1, pp. 24-34.

Spanbauer, S. J. 1995. Reactivating higher education with

total quality management: using quality and

productivity concepts, techniques and tools to improve

higher education, Total Quality Management, Vol. 6,

No. 5/6.

Thakur, R. et al. 2006. CRM as strategy: Avoiding the

pitfall of tactics, Marketing Management Journal, Vol.

16, Issue 2, 147-154.

Zablah, A.R, Bellenger, D.N and Johnston, W. J. 2004. An

evaluation of divergent perspectives on customer

relationship management: Towards a common

understanding of an emerging phenomenon .Industrial

Marketing Management, 475–489.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

274