Weather Effect on Apparel Sales in France

Jean-Louis Bertrand and Xavier Brusset

ESSCA School of Management, Angers, France

Keywords:

Supply Chain Management, Weather Risk Management, Apparel Distribution, Statistical Model.

Abstract:

In 2012, French apparel industry suffered weak sales for the fifth consecutive year. Even if economic condi-

tions were not favorable, trade professionals feel that the weather played a significant role. Its impact on retail

sales in general has not been formally quantified. This has become an urgent issue as climate change is ag-

gravating naturally occurring climate variability and is becoming a source of uncertainty for climate-sensitive

economic sectors. In this paper we provide managers with tools to evaluate the impact of temperature anoma-

lies on sales volumes. We present a statistical method to separate out the weather effect from the underlying

real performance of apparel sales. The model has been developed for the retail economic sector but can be

extended to all fast moving consumer goods both in France and abroad. These models are applicable to supply

chain managers and business analysts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Weather is a powerful force affecting the economy.

Abnormal weather conditions can shift the timing of

purchases or result in a total loss of demand. Weather

is a risk factor for business and government. Retailers

often talk about how adverse weather impacts their

sales and/or earnings. Witness, for example, the July

6, 2005, statement on second-quarter earnings by Pe-

ter Harris, CEO of West Marine, who said of his com-

panys sales: “As one would expect, continuing poor

weather in April and May on both coasts dampened

second quarter sales, especially when compared to the

great spring weather we enjoyed last year”. In the fol-

lowing, we present both a method for computing the

impact of the weather on economic activity and an il-

lustration using the retail sales in the apparel industry

in France as recorded by the Institut Franc¸ais de la

Mode (IFM).

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The impact of weather on economic activity has been

acknowledged as being large in most economic sec-

tors in all countries (Howarth and Hoffman, 1984; El-

lithorpe and Putnam, 2000). In some industries such

as agriculture and energy, weather is such a risk factor

that it is tracked, documented and hedged through risk

management instruments (Roll, 1984; Lee and Oren,

2009).

Although the impact of the weather on behavior

has been explored in fields such as finance, energy

consumption and psychology, it has been largely ig-

nored in the marketing literature. (Stoltman et al.,

1999) used weather conditions as one of six fac-

tors that affect behavioral reactions while shopping

for clothes. (Conlin et al., 2007) found evidence

of weather-related projection bias of catalogue sales.

However, there is now more than anecdotal evidence

that firms try to incorporate weather variables into

their sales forecasting models. For example, Wal-

Mart lowered its June 2006 sales forecasts due to un-

usually cool summer weather (Murray et al., 2010).

The impact of the weather on retail sales has been

recognized now for a long time (Steele, 1951). It

has been studied with varying conclusions. (Linden,

1959) studied the effects on New York City depart-

ment stores of rain, sunshine, temperature and snow

on the ground during business hours, finding few sys-

tematic effects. (Swinyard, 1993; Babin and Dar-

den, 1996; Groenland and Schoormans, 1994) fo-

cused on the link between consumer mood, behavior

and weather. To mitigate the effects of the weather on

sales in fashion retail, (Caliskan Demirag, 2013) stud-

ied the effectiveness of weather-conditional rebates

applied by numerous retail and manufacturing orga-

nizations to promote a variety of products from toys

to health and beauty items with cash values incentives

when weather conditions are unfavorable.

277

Bertrand J. and Brusset X..

Weather Effect on Apparel Sales in France.

DOI: 10.5220/0004918802770281

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES-2014), pages 277-281

ISBN: 978-989-758-017-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

In the particular sector of garment and apparel dis-

tribution, (Bahng and Kincade, 2012) provide strong

evidence that fluctuation in temperature can impact

sales of seasonal garments on a daily basis. However,

no evidence has been found to substantiate an impact

on sales of a whole season. (Rowley, 1999) prove

what retailers had long suspected, ie, that precipita-

tion affected substantially actual clothing purchases.

The classic example can be found in the northern

hemisphere: the placement of Easter in the calendar

affects seasonal retail sales pattern depending upon

whether it is in early March or late April. Generaliz-

ing, (Starr-McCluer, 2000) estimated that the effect of

weather on retail sales in the United States has a small

but statistically significant role in explaining monthly

retail sales.

3 DATA AND METHODS

3.1 Data

The analysis of this relationship relies on choosing

the most representative set of economic output, rele-

vant weather data, and appropriate quantitative tech-

niques. The objective is to prove the existence of a

statistically significant relationship and establish the

weather-sensitivity relationship in the case of textile

and clothing.

3.1.1 Defining Weather Sensitivity

Weather exposure is the amount of revenues or costs

at risk, which results from changes in weather con-

ditions (Brockett et al., 2005). Many businesses ex-

perience some form of seasonal pattern in their activ-

ity. For example, electricity consumption is higher in

winter than in summer, ice cream sales are stronger

in summer than in winter, and so on. Business man-

agers can execute their plans as long as the weather

patterns remain typical. Potential gains or losses arise

when weather conditions unexpectedly deviate from

their normal values. Meteorologists refer to these

deviations as weather anomalies. Because they are

unexpected, weather anomalies, or weather surprises

(Roll, 1984), can potentially change the economic

performance of a firm or a sector. Normal weather

conditions are calculated as the average weather over

30 years (Baede, 2001; Dischel, 2002).

The average weather is the climate. Climate vari-

ability is the extent to which actual weather differs

from this climate. Climate variability causes potential

disruption in economic conditions (Dischel, 2002).

How much less will the ice-cream producer sell if

the temperature is cooler than normal? How much

more will the motorway operator spend to clear roads

if snowfall is higher than in a typical winter? An

economic sector is considered to be weather sensi-

tive if weather anomalies can explain a percentage of

the performance of the sector. In other words, a sec-

tor is weather sensitive if it is possible to establish a

statistically significant relationship between weather

anomalies and change in revenues: The stronger the

relationship, the higher the sensitivity to weather.

3.1.2 Time Series from the Institut Franc¸ais de

la Mode

The first weather-sensitivity research papers focused

on U.S. economic output. Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) or gross state product data for the 11 non-

governmental sectors were used as a measure of eco-

nomic activity principally because time-series were

sufficiently long to apply statistical analysis (Dutton,

2002; Larsen, 2006; Lazo et al., 2011).

Similarly, one important data source which could

have been used are monthly turnover indices pub-

lished by the French National Bureau of Statistics

(INSEE). These indices aggregate turnover figures of

firms falling within the scope of value-added tax pay-

ment. They are available at the most detailed level of

the European classification of activities. More impor-

tant, turnover indices are volume-based, which make

them particularly relevant as a base for testing the im-

pact of weather anomalies, as weather risk is a volume

risk (Brockett et al., 2005; Barrieu, 2003; Dischel,

2002). Though data starts in January 1995, only two

sectors could have been used for our analysis (tex-

tile retail sales in specialized stores and retail sale via

stalls and markets of textiles, clothing and footwear).

Moreover, the level of detail is insufficient.

We used data provided by IFM, the French Insti-

tute of Fashion. Researchers from the Economic Ob-

servatory of IFM have been gathering sales figures

in volume from a panel of thousands of textile and

clothing retailers across France since January 2000.

Panel members range from independent multi-brand

clothing stores to specialized single brand chain stores

and department stores. Data is available by garment

type for women, men and children. Sales figures are

compiled and analyzed by IFM in a survey (Distribi-

lan) to highlight major trends and changes by product

category and distribution channel year on year on a

monthly basis (see table 1).

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

278

Table 1: Apparel categories and distribution channels as used by the Institut Franc¸ais de la Mode.

Category Product Distribution Channels

Ready-To-Wear Independent Stores

Women Small Garments Department Stores

Underwear Mass Merchant, Factory Outlets

Ready-To-Wear Online

Men Small Garments Hypermarkets

Underwear Large Distribution Chains

Children Children’s Clothes Specialty Chain Stores

Haberdashery - Knitting Wool Multi-Brand Independent Stores

Other Fabric By Meter

Household Linen

3.1.3 Weather Data

The choice of weather variables is a key step of the

process. IFM sales figures are produced at national

level, whereas weather is a local risk. On a given

day at a given time, weather conditions are different

in Paris, in Brest in western France, and in Marseille

in southern France (Barrieu, 2003). IFM indices add

revenues from all regions at a national level. There-

fore, weather variables must be constructed in such a

way that they not only are a valid representation of

national weather conditions but also can capture po-

tential weather signals at a national level. In 2002,

M

´

et

´

eo France and Powernext developed a range of

national temperature indices (NextWeather), initially

aimed at the financial community to serve as a base

for derivative instruments. They constructed the tem-

perature index to fit the geographical distribution of

economic activity. M

´

et

´

eo France selected 22 rep-

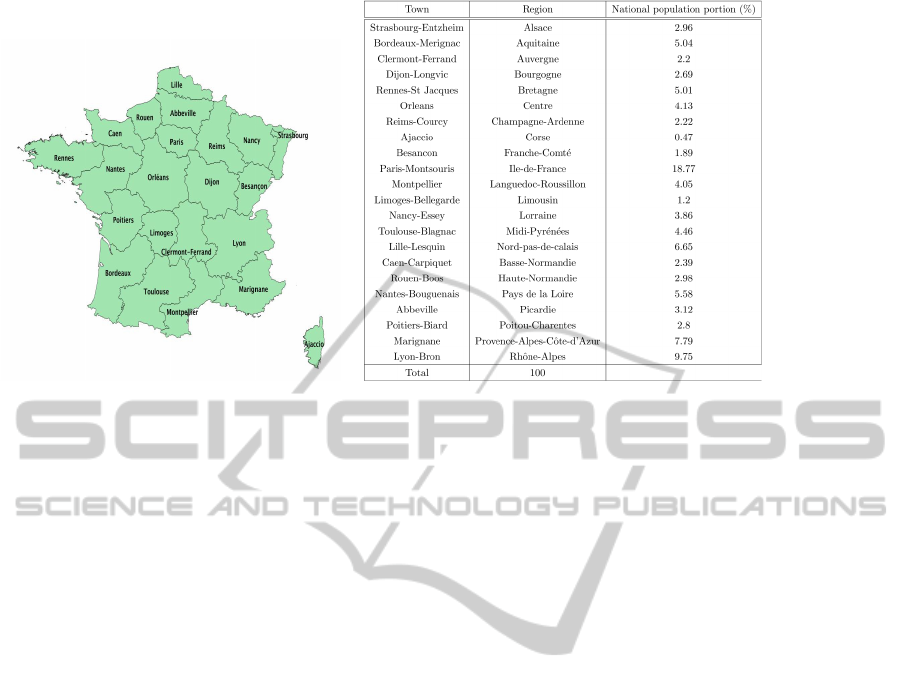

resentative weather stations (figure 1) and weighted

daily data from each station by the population in

each region to construct national temperature indices

(Bertrand, 2010).

We applied the methodology developed by M

´

et

´

eo

France to construct our set of weather data. We used

certified temperature and precipitation data from the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA). To facilitate the replication of our work, it is

important to detail the calculation process using one

example. For each month m of year y, we calculated

the national temperature index T

m,y

as follows:

T

m,y

=

22

∑

s=1

l

m

∑

d=1

1

l

m

p

v

p

total

·t

d,s,m

, (1)

where t

d,v,m

is the average temperature of day d of

year y in the weather station s of the 22 representative

cities, l

m

is the number of days within the month m, p

v

the regional population and finally p

total

the total pop-

ulation for all regions. Since we defined weather sen-

sitivity as the exposure to weather anomalies, we cal-

culated weather anomalies as the difference between

the observed value and its “normal” value. For the

current studys purposes, the normal value is the aver-

age observation over 30 years (19832012) as defined

by the World Meteorological Office. For each month

m of year y, the national temperature index anomaly

T

0

m,y

is given by the difference between the monthly

national temperature index T

m,y

and the average of the

same index over 30 years:

T

0

m,y

= T

m,y

−

1

30

2012

∑

y=1983

T

m,y

(2)

4 MODEL SELECTION

4.1 Times Series: Stationarity and Lags

A common assumption in time series analysis is that

the data are stationary. Stationary series follow an

accurate mathematical definition, which, for the pur-

poses of the current study, is summarized by taking

to mean that a stationary process has the property that

the mean, variance, and autocorrelation structures are

constant over time. This property means that station-

ary series are trendless with no seasonal fluctuations.

There are several precise statistical tests on station-

arity, of which the DickeyFuller one (Greene, 2011).

This test applied to our data confirmed our assump-

tion that all series are stationary. To test whether tex-

tile sales anomalies can be explained by temperature

anomalies, we built the following linear models:

α

m,y

= α + βT

0

m,y

+ ε, (3)

where α

m,y

is the apparel sales anomaly of month

m and year y, T

0

m,y

the national temperature index

WeatherEffectonApparelSalesinFrance

279

Figure 1: Regions of France and share of total population.

anomaly, ε a random variable following a normed

and centered distribution, and α and β the coefficients

which we need to estimate. The textile industry is

season-driven so we assumed that the sensitivity to

weather for each month does not change within the

same season. We therefore tested each model, for

each of the four seasons to build each model. The

models use the unexpected change in sales volumes

which may be explained by unexpected changes in

weather conditions as represented by temperatures.

For each model, we tested the significance and the fit

of the linear regression.

5 MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

The present study is the first research work which ana-

lyzes the impact of temperature anomalies on sales in

the entire apparel sector at regional level for a whole

country. We calculate the sensitivity to weather of

each product category, for each distribution channel,

for men, women and children. As a result, we show

how to remove the impact of weather on the histor-

ical apparel sector performance to display the true

organic performance. We show how to specifically

identify periods of the year which exhibit the high-

est exposure to changes in weather conditions. And

finally, we provide “sales at risk” results thanks to a

deep weather database to determine the average and

the maximum potential losses which can be caused

by extreme weather conditions by product category,

by distribution channel. The fact that weather has an

impact on apparel sales is not new to retailers. For the

first time however, our findings formalize the relation-

ship between weather and apparel sales and provide

retailers with invaluable information about their per-

formance excluding weather effect and about their ex-

posure to weather. Such modeling also allows for risk

management instruments such as weather derivatives

or weather insurance to be implemented to protect re-

tailers from losses caused by unfavorable weather.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has been written using material collected

with the help of the Institut Franc¸ais de la Mode. We

would also wish to thank Meteo-Protect for providing

us with curated and certified weather data.

REFERENCES

Babin, B. J. and Darden, R. (1996). Good and bad shopping

vibes: spending and patronage satisfaction. Journal of

Business Research, 35(3):201–206.

Baede, A. P. M. (2001). Climate change 2001: Working

group i: The scientific basis. appendix i - glossary.

Technical report, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change (IPCC).

Bahng, Y. and Kincade, D. (2012). The relationship be-

tween temperature and sales. International Journal of

Retail and Distribution Management, 40(6):410–426.

Barrieu, P. (2003). Introduction aux produits d

´

eriv

´

es clima-

tiques. Journal de la Soci

´

et

´

e Franc¸aise de Statistique,

144(3):53–68.

Bertrand, J.-L. (2010). La gestion du risque m

´

et

´

eorologique

en entreprise. PhD thesis, Universit

´

e Paris Ouest Nan-

terre La D

´

efense.

Brockett, P., Wang, M., and Yang, C. (2005). Weather

derivatives and weather risk management. Risk Man-

agement and Insurance Review, 8(1):127–140.

ICORES2014-InternationalConferenceonOperationsResearchandEnterpriseSystems

280

Caliskan Demirag, O. (2013). Performance of weather-

conditional rebates under different risk preferences.

Omega, 41:1053–1067.

Conlin, M., O’Donoghue, T., and Vogelsang, T. J. (2007).

Projection bias in catalogue orders. The American

Economic Review, 97(4):1217–1249.

Dischel, R. (2002). Climate Risk and the Weather Market:

Financial Risk Management with Weather Hedges,

chapter Introduction to the weather market: Dawn to

mid-morning, pages 25–41. Risk Books, London.

Dutton, J. (2002). Opportunities and priorities in a new era

for weather and climate services. Bulletin of American

Meteorological Society, 83(9):1303–1311.

Ellithorpe, D. and Putnam, S. (2000). Weather derivatives

and their implications for power markets. The Journal

of Risk Finance, 1(2):19–28.

Greene, W. (2011). Econometric Analysis. Prentice Hall,

Upper Saddle river, NJ, USA, 7th edition edition.

Groenland, E. A. and Schoormans, J. P. L. (1994). Com-

paring mood-inducion and affective conditioning as

mechanisms influencing product evaluation and prod-

uct choice. 11:183–197.

Howarth, E. and Hoffman, M. S. (1984). Amulti dimen-

sional approach to the relationship between mood and

weather. British Journal of Psychology, 75(1):05–23.

Larsen, P. H. (2006). Estimating the sensitivity of u.s. eco-

nomic sectors to weather. Working Paper, Cornell

University.

Lazo, J. K., Lawson, M., Larsen, P. H., and Waidmann,

D. M. (2011). U.s. economic sensitivity to weather

variability. Bulletin of American Meteorological Soci-

ety, 92:709–720.

Lee, Y. and Oren, S. (2009). An equilibrium pricing model

for weather derivatives in a multi-commodity setting.

Energy Economics, 31:702–713.

Linden, F. (1959). The business of department stores. Tech-

nical report.

Murray, K., Di Muro, F., Finn, A., and Popkowski Lesz-

cyc, P. (2010). The effect of weather on consumer

spending. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Ser-

vices, 17:512–520.

Roll, R. (1984). Orange juice and weather. The American

Economic Review, 74(5):861–880.

Rowley, J. (1999). Loyalty, the internet and the weather;

the changing nature of the marketing information sys-

tems. Management Decision, 37:514–518.

Starr-McCluer, M. (2000). The effect of weather on retail

sales. Technical report.

Steele, A. T. (1951). Weather’s effect on sales of a depart-

ment store. Journal of Marketing, 15:436–443.

Stoltman, J. J., Morgan, W. F., and Anglin, K. L. (1999).

An investigation of retail shopping situations. Inter-

national Journal of Retail and Distribution Manage-

ment, 27(4):145–153.

Swinyard, W. R. (1993). The effects of mood, involve-

ment and quality of store experience on shopping in-

tentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2):271–

293.

WeatherEffectonApparelSalesinFrance

281