A Knowledge Management Framework for Knowledge-Intensive

SMEs

Thang Le Dinh

1

, Thai Ho Van

1

and Éliane Moreau

2

1

Laboratory for Enterprise Development in Developing Countries, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières,

Trois-Rivières, Canada

2

Institut de recherche sur les PME, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, Canada

Keywords: Conceptual Framework, Knowledge Management, Knowledge-Intensive Enterprises, SMEs.

Abstract: Nowadays knowledge-intensive enterprises, which offer knowledge-based products and services to the

market, play a vital role in the knowledge-based economy. Effective knowledge management has become a

key success factor for those enterprises in particular and the whole economy in general. Knowledge

management is important for both large and small and medium knowledge-intensive enterprises; however,

there is still a little focus on this topic in knowledge-intensive small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In this

study, the authors propose an integrated framework as a foundation for designing an appropriate knowledge

management solution for knowledge-intensive SMEs. The paper begins with a theoretical background and

the research design and then continues with the characteristics of the framework. Accordingly, the principal

components of the framework corresponding to design science research such as the constructs, model,

method and instantiations are illustrated. The paper ends with the conclusions and future work.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge-intensive enterprises (KIE) play an

important role in the knowledge-based economy

(OECD, 2007). Knowledge-intensive enterprises can

be loosely and preliminary defined as organizations

that offer to the market the use of fairly sophisticated

knowledge or knowledge-based products and

services (Doloreux and Shearmur, 2011).

Knowledge management is important for both large

enterprises and small and medium-size enterprises

(SME). As a matter of fact, many topics related to

knowledge management in SMEs have not been well

studied yet (Durst and Edvardsson, 2012). Given the

importance of effective knowledge management in

knowledge-intensive SMEs (KI-SME), there is a

special need for more research on this topic. An

appropriate knowledge management framework for

KI-SMEs may help them to manage their business

activities effectively, to improve their performance

and innovation capacity, and also contribute to the

development of the economy as a whole.

This paper is organized as follows. Following the

introduction, the paper begins with theoretical

background and research design, and then continues

with the characteristics of the proposed framework.

Accordingly, the principal components of the

framework for KI-SMEs are presented. The paper

ends with a short discussion and conclusion,

including implications for research and practice.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Knowledge-intensive enterprises are organizations

that assist others in solving problems and making

business decisions that require external sources of

knowledge (Miles, 2005). KIEs often provide

products and services that get involved in activities

to create the values of knowledge collection,

enhancement, and dissemination (Miles et al., 1995).

The two groups of KIEs are technology KIEs and

professional KIEs (Shearmur and Doloreux, 2008).

Technology KIEs perform activities related to

information technology, research and development,

architecture and engineering activities and related

consultancy, testing and technical activity’s analysis.

In professional KIEs, the following activities are

included: legal sectors, accounting, bookkeeping and

auditing activities, tax consultancy, market research,

as well as the entire advertising industry. Moreover,

there are three characteristics of KIEs (Miles et al.,

435

Le Dinh T., Ho Van T. and Moreau É..

A Knowledge Management Framework for Knowledge-Intensive SMEs.

DOI: 10.5220/0004950404350440

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 435-440

ISBN: 978-989-758-029-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

1995). Firstly, activities of KIEs are mainly based on

professional knowledge. Secondly, KIEs either use

their own sources of information and knowledge in

their activities or external knowledge sourcing in

services for their clients or suppliers (Clausen,

2013). Finally, the competitive edge of KIEs is that

they are the primary knowledge suppliers for their

clients when they expect to perform and innovate

(Harris et al., 2013).

Knowledge and intellectual capital are

increasingly recognized as the main sources of

competitive advantages in the knowledge-based

economy (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995;

Steinmueller, 2002; Daud and Yusoff, 2010). For

this reason, knowledge is one of the key elements in

the success of KIEs (Muller and Doloreux, 2007).

The main focus of KIEs is on knowledge creation,

transfer and development (Miles, 2005). Therefore,

effective knowledge management is a question of

survival for KIEs (Scarso and Bolitani, 2010).

Organizations realize that they need to pay more

attention to knowledge management and social

capital (Daud and Yusoff, 2010). Knowledge

management influences social capital; social capital

affects organizational performance, and the

integration of knowledge management and social

capital can improve organizational performance and

innovation capacity (Daud and Yusoff, 2010; Harris

et al., 2013).

For SMEs, knowledge management is

recognized as the key strategy to deal with the

complexities and changes in the modern economy

(Beijerse, 2000; Jetter et al., 2006). Applying

knowledge management activities may bring various

benefits to SMEs such as staff development,

innovation enhancement, improved customer

satisfaction and external relationships, increased

sales growth and decreased losses (Edvardsson and

Durst, 2013). Although both large and SMEs

recognize the role of knowledge management as a

vital competitive edge, research on knowledge

management in SMEs has been received a little

focus. Since SMEs only apply knowledge

management at the operational level, systematic

knowledge management practices need to be

adopted in these enterprises (Beijerse, 2000). Indeed,

SMEs face major challenges in the implementation

of knowledge management projects such as the lack

of human and financial resources (Durst and

Edvardsson, 2012).

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

This paper seeks to answer the following research

question: “What is the appropriate knowledge

management framework for KI-SMEs?”

In order to explore this research question, we

used a design science research framework, which is

particularly useful for creating and evaluating IT

artefacts for solving identified organizational

problems. The framework includes fundamental

components such as a set of constructs, a model, a

method and a set of instantiations (March and Smith,

1995; Vaishnavi and Kuechler, 2004).

The main purpose of this study is to propose a

conceptual framework for building a knowledge

management solution for various types of KI-SMEs

that need to overcome the key challenges related to

human and financial resources. Consequently, the

characteristics of the proposed framework, called

NIFO, can be represented by its four attributes:

Natural, Incremental, Focal, and Open. The natural

attribute of the framework can assist KI-SMEs in

convincing their employees to participate actively in

the knowledge management process in an informal

and appropriate way corresponding to their habits

and culture in order to transform the business

information produced and used in daily activities

into organizational knowledge. The incremental

attribute can help enterprises implement the

knowledge management project step-by-step and in

an evolutionary way depending on their

organizational growth level. The focal attribute

supports enterprises to focus on knowledge

management for core products and services

according to their business priority. The open

attribute allows enterprises to manage actively their

projects and to overcome the challenges related to

human and financial resources by co-operating and

innovating together as well as by using open source

solutions.

The NIFO framework has two levels: design and

implementation. At the design level, enterprises can

understand extensively the values of knowledge to

design the appropriate knowledge management

solution, starting with core activities (focal attribute)

and then applying the knowledge management

system step-by-step (incremental attribute). At the

implementation level, the model helps enterprises to

implement the system effectively to motivate

employees to create explicit knowledge from tacit

knowledge in a natural way (natural attribute) at the

lowest costs (open attribute).

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

436

4 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

FRAMEWORK FOR KI-SMEs

4.1 Constructs of the Framework

The constructs of the NIFO framework are different

types of concepts related to the business information

and knowledge produced and used in daily business

activities. For this reason, the constructs need to

represent the characteristics of knowledge such as

the structure, transition, possession and coherence of

knowledge.

The structure of knowledge is represented by the

“know-what” that describes knowledge that relates

to a phenomenon of interest (Garud, 1997). Know-

what is often generated through ‘learning-by-using’.

Know-what in a KI-SME focuses on products,

services or intellectual capital of the organizations.

This construct describes what types of information

exist, their structures, as well as their interrelations.

The key concept of this construct is the classes. A

class is defined as an object type and a set of objects

of this type. An attribute of a class is a function

corresponding to every object of this class and to a

set of objects of other classes.

The transition of knowledge is represented by the

“know-how” that describes the understanding of the

generative processes that constitute phenomena

(Garud, 1997). Know-how is generated through

‘learning-by-doing’, which has been represented by

the concept of processes. A process is a feedback of

the organization to the occurrence of an event or a

situation. A process may perform a transformation

of a set of dynamic states.

The possession of knowledge is represented by

the “know-who” that describes groups or individuals

who may provide resources related to domain

knowledge. One way to obtain know-who is

‘learning-by-working-together’ that aims at

participating and co-operating with others. This

construct describes who may be knowledgeable

about a specific knowledge. Its key concept is the

concept of zone of responsibilities (ZoR). In KIEs,

this construct often includes the knowledge about

who-know-what and who-know-how.

The coherence of knowledge is represented by

the “know-why” that describes the understanding of

the principles underlying phenomena. This construct

is represented by the rule aspect that concerns the

coherence of information. Its key concept is the

concept of business rules (BR). Scopes of a BR

represent the business context that covers a set of

classes. Risks of a BR are the possibilities of

suffering the incoherence of information that relates

to a set of processes.

4.2 Model of the Framework

The model of the NIFO framework aims at

expressing the relationships among the concepts that

can be specified using simplified Unified Modeling

Language (UML) notation (Rumbaugh et al., 1999).

KI-SMEs can use this model to represent the

conceptual specification of their knowledge base. In

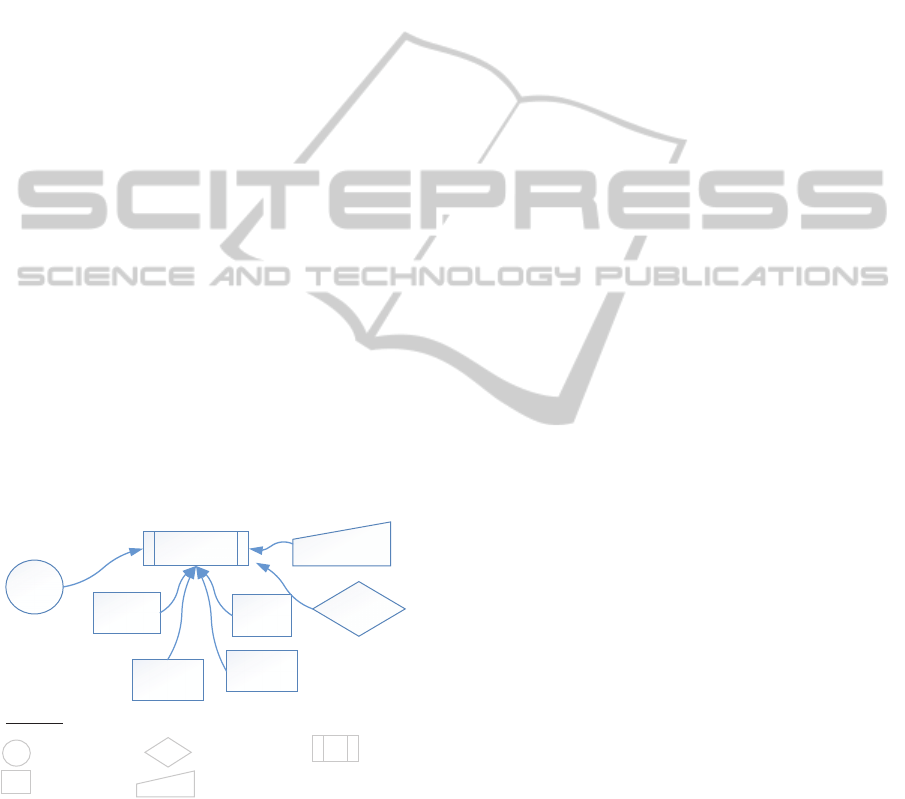

Figure 1, each class of UML represents a key

concept of our framework. The structure of

knowledge is represented by concepts such as

classes and their attributes. A method of a class

performs a specific function. The transition of

knowledge is represented by processes and dynamic

states. A process performs a transformation of

information that invokes a set of methods and

changes a set of dynamic states. The possession of

knowledge is represented by a zone of

responsibilities that describes the relation between

know-who with know-what or know-how. The

coherence of knowledge is represented by business

rules. The scope of a rule represents a set of classes

as a semantic context within which it operates. The

risks of a rule relate to a potential incoherence in the

information that concerns a set of attributes and

involves a set of methods.

Figure 1: Model of the NIFO framework.

4.3 Method of the Framework

The method of the NIFO framework is a set of

activities supporting the process of knowledge

management. We adopted four knowledge

conversions (combination, internalization,

Class Process

Integrityrule

Dynamicstate

Me tho d

Scope Risk

Attribute

1

*

1

*

1

*

FromStates

ToStates

1

*

1*

Involvedin

Zoneofresponsibilities

KNOW‐WHAT

KNOW‐HO

W

KNOW‐WH

O

KNOW‐WH

Y

Who‐know‐how

Who‐know‐what

AKnowledgeManagementFrameworkforKnowledge-IntensiveSMEs

437

externalization and socialization) and five

knowledge enablers (vision, strategy, staff, structure,

and system) proposed by Nonaka and Takeuchi

(1995) as a foundation for our method.

Figure 2 presents the overall architecture of the

knowledge management system (Alavi and Leidner,

2001). We consider a knowledge management

solution in a KIE as a service system that needs to

take into account the three dimensions of service

science: Management, Science and Engineering (Le

Dinh and Pham Thi, 2012).

Figure 2: Method of the NIFO framework.

The management part is related to the effectiveness

of enterprises with the objective of enhancing

effectiveness and coordination with partners. This

part concerns the value creation chain of the

enterprise and corresponds to three knowledge

enablers: Vision, Strategy and Staff. Firstly, KI-

SMEs must determine their knowledge vision and

strategy, which must be conformed to business

strategy and priority. Secondly, they also need to

pay attention to working with staff for promoting

knowledge sharing and for a cross-levelling of

knowledge.

The science part is related to business

information, especially to the process of collecting

data and transforming data into information. The

focus of this part is on determining which good and

innovative products and services they can supply to

clients and how to supply them. In other words, this

part focuses on knowledge about business activities

of enterprises. The science part corresponds to the

structure knowledge enabler that redefines the

organizational structure to promote and facilitate the

knowledge management and conversions.

Additionally, this part is also necessary to customize

the framework and to build the knowledge hierarchy

model of the organization.

The engineering part is related to knowledge that

is defined as the use of business information to

create added values. This part focuses on knowledge

about the processes of performing tasks in

organizations. The engineering part corresponds to

the system knowledge enabler that aims at

implementing networking communities of

knowledge.

4.4 Instantiations of the Framework

The instantiations related to the experimentation of

the framework are the focal point of our present and

future work. The instantiation presented hereafter is

related to a KI-SME that offers IT services and

resources in a developing country. This SME has

about 30 employees who are mostly team leaders

and software developers. The demand for IT

professionals in this developing country is rather

high; therefore, employees often leave the SME to

work for large enterprises. Knowledge management,

especially training and knowledge transferring to

new employees, is a survival factor for this SME.

Concerning the method, the business priority of

the SME is to provide better knowledge-intensive

services to its customers. Therefore, the knowledge

management solution needs to promote both

innovation in services and innovation in service

processes. Accordingly, all of the four knowledge

conversions have been used to promote the learning

process and intellectual capital (Nonaka and

Takeuchi, 1995). The SME has used an open-source

platform, which supports the reconciliation of e-

collaboration and knowledge management systems

(Le Dinh et al., 2013). The taxonomy system has

been organized based on the concepts of the NIFO

framework. Each content is associated to one or

several tags of the taxonomy (i.e. types of

knowledge components). At the group level, the

SME organized several teams. Each team has 3 to 8

persons, who work on a same project and use a

common working space in the platform. Related to

the socialization conversion, tacit knowledge can be

shared through forum discussion, chat and video

conference functions. Related to the externalization

conversion, all written documents, Q&A, and

presentations have been classified and shared within

and between teams. Related to the combination

conversion, a wiki system has been used at the

organizational level. All of the content is being

collected and classified in order to form the new

content as wiki pages. Those wiki pages are linked

based on their tags. Related to the internalization

conversion, the SME motivates its employees to

consult the wiki system when doing their tasks and

also to give comments on the wiki pages.

Concerning the model, the SME has decided to

begin with the concepts such as class, attribute,

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

438

process, rule, scope, risk and zone of

responsibilities. The other concepts such as method

and dynamic state have been foreseen for the next

step.

Concerning the construct, the structure of

knowledge concerns the knowledge related to its

services, represented by the “Service” class. The

“Service” class may have attributes such as “Start

date”, “End date”, “Contact person”, “Estimated

cost”, and “Actual cost”. Related to the transition of

knowledge inside the KI-SME, there are process

concepts that relate to the “Service” class concept

such as “Service proposal”, “Service design”,

“Service implement”, and “Service operation”.

Related to the possession of knowledge, there are a

ZoR, related to the “Service” class as a who-know-

what, and several ZoRs related to the processes of

“Service proposal”, “Service design”, “Service

implement”, and “service operation” processes as

who-know-how. Finally, the coherence of

knowledge must correspond to the goal of the SME,

which aims at improving the satisfaction of its

customers by controlling effectively project schedule

and budget. Accordingly, there is a business rule

about the relationship between “Estimated cost” and

“Actual cost”. The management of the KI-SME has

decided that the difference between those two costs

should be less than 10% of the estimated cost. The

scope of this rule is the “Service” class. The risks

concern the processes such as “Service proposal”,

“Service design”, “Service implement”, and

“Service operation”.

Know‐what

Notation:

Know‐why

Know‐who

Know‐how

Zoneof

responsibilities

Service’sZoR

Whoknow

what

Service

Service

proposal

Service

design

Service

implement

Cost

control

Service

operation

Figure 3: Excerpt of the constructs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have presented an appropriate

knowledge management framework for knowledge-

intensive enterprises (KIE) with a focus on the

particularities of knowledge-intensive small and

medium enterprises (KI-SME). Accordingly, the

framework, called NIFO framework, has four main

attributes: Natural, Incremental, Focal, and Open.

We believe that our work is one of the first

approaches that focuses on building a knowledge

management solution for KI-SMEs based on the

perspective of knowledge components. To answer

our research question, we proposed a framework for

knowledge management and conversions that

consists of different artefacts with different levels of

abstraction: constructs, model, method, and

instantiations. With regard to practical implications,

when a KI-SME intends to build its knowledge

management solution¸ the NIFO framework

provides a starting point to determine and organize

knowledge according to their knowledge

components such as know-what, know-how, know-

who and know-why.

Concerning the related work, there are

approaches that suggested the concept of knowledge

audit as the initial process in knowledge

management (Choy et al., 2004; Perez-Soltero et al.,

2009). Our approach shares the common strategy of

those approaches serving as an integrated approach

for knowledge management. Compared to Choy et

al. (2004), the NIFO framework includes the

constructs, model, method and instantiations;

however, the approach of Choy et al. (2004) focuses

more on the method, including different phases in a

systematic manner. Compared to Perez-Soltero et al.

(2009), the NIFO framework also has more

dimensions at different levels. The approach

proposed by Perez-Soltero et al. (2009) is based on

ontology that corresponds essentially to the structure

of knowledge. Furthermore, our framework is not

only useful for collecting, storing, and analysing

knowledge, but also for developing new knowledge

to support different types of innovation related to

products, services and business processes in KI-

SMEs.

Currently, we are working on building an

intranet-based knowledge management system based

on an open-source content management platform so

that SMEs could reuse and enhance this system as

their solution at lower costs.

Concerning the future work, we intend to

experiment our framework with some specific

knowledge-intensive industries in the fields of

business, research and development, educational and

health-care services.

AKnowledgeManagementFrameworkforKnowledge-IntensiveSMEs

439

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincerely

thank to the FRQSC (Fonds de recherche sur la

société et la culture) of the Government of Quebec,

Canada for the financial support for this research.

REFERENCES

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. 2001. “Knowledge

management and knowledge management systems:

Conceptual foundations and research issues”, MIS

Quarterly, 25 (1), pp. 107-136.

Beijerse, R. P. 2000. “Knowledge management in small

and medium-sized companies: Knowledge

management for entrepreneurs”, Journal of Knowledge

Management, 4(2), 162 – 179.

Choy, S. Y., Lee, W. B., & Cheung, C. F. 2004. “A

systematic approach for knowledge audit analysis:

Integration of knowledge Inventory, mapping and

knowledge flow analysis”, Journal of Universal

Computer Science,10(6), 674-682.

Clausen, T. H. 2013. “External knowledge sourcing from

innovation cooperation and the role of absorptive

capacity: Empirical evidence from Norway and

Sweden”, Technology Analysis & Strategic

Management, 25(1) 57-70.

Daud, S., & Yusoff, W. F. W. 2010. “Knowledge

management and firm performance in SMEs: The role

of social capital as a mediating variable”, Asian

Academy of Management Journal,15(2), 135–155.

Doloreux, D. & Shearmur, R. 2011. “Collaboration,

Information and the Geography of Innovation in

Knowledge Intensive Business Services,” Journal of

Economic Geography. DOI:10.1093/jeg/lbr003

Durst, S., & Edvardsson, I. R. 2012. “Knowledge

management in SMEs: A literature review”, Journal of

Knowledge Management, 16(6), 879-903.

Edvardsson, I. R., & Durst, S. 2013. “The benefits of

knowledge management in small and medium-sized

enterprises”, Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 81, 351-354.

Garud, R. 1997. “On the distinction between know-how,

know-what, and know-why”, Advances in Strategic

Management. JAI Press, 81-201.

Harris, R., McAdam, R., McCausland, I. & Reid, R. 2013.

“Knowledge management as a source of innovation

and competitive advantage for SMEs in peripheral

regions”, International Journal of Entrepreneurship &

Innovation, 14(1), 49-61.

Jetter, A., Kraaijenbrink, J., Schröder, H., & Wijnhoven,

F. 2006. Knowledge Integration: The Practice of

Knowledge Management in Small and Medium

Enterprises. Physica-Verlag.

Le Dinh, T. & Pham Thi, T.T. 2012. “Information-driven

Framework for Collaborative Business Service

Modelling”, International Journal of Service Science,

Management, Engineering, and Technology, Vol.3,

No.1, pp: 1-18, IGI Global.

Le Dinh T., Rinfret, L., Raymond, L., Dong Thi, B.T.

2013. “Towards the reconciliation of knowledge

management and e-collaboration systems”,

Interactive Technology and Smart Education, Vol.10

No.2, pp.95-115, Emerald.

March, S. T., & Smith, G. S. 1995. “Design and natural

science research on information technology”, Decision

Support Systems, 15 (4), 251-266.

Miles, I. (2005). “Knowledge intensive business services:

Prospects and policies”, Emerald Group Publishing

Limited, 7(6), 39-63. DOI 10.1108/1463668051

0630939

Miles, I., Kastrinon, N., Flanagan, K., Bilderbeek, R., den

Hertog, P., Huntink, W., & Bouman, M. 1995.

“Knowledge-intensive business services: Their roles

as users, carriers and sources of Innovation”, The

University of Manchester.

Muller, E., & Doloreux, D. 2007. “The key dimensions of

knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS)

analysis. A decade of evolution”, Arbeitspapiere

Unternehmen und Region, U1. Retrieved from

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0011-n-549957

Nonaka I., & H. Takeuchi. 1995. The knowledge-creating

company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press,

USA.

Oganization for Economic Co-Operation and

Development (OECD). 2007. Innovation and

knowledge-intensive services activities. OECD

Publishing, Paris, 2007.

Perez-Soltero, A., Barcelo-Valenzuela, M., Sanchez-

Schmitz, G., & Rodriguez-Elias, O. M. (2009). “A

computer prototype to support knowledge audits in

organizations”, Knowledge and Process Management,

16(3), 124–133. doi:10.1002/kpm.329

Rumbaugh, J., Jacobson, I., & Booch. G. 1999. The

unified modeling language reference manual. Addison

Wesley Longman, Amsterdam.

Scarso, E, & Bolisani, E. 2010. “Knowledge-based

strategies for knowledge intensive business services:

A multiple case-study of computer service

companies”, Electronic Journal of Knowledge

Management, 8(1), 151-160. Retrieved from at

www.ejkm com

Shearmur, R., & Doloreux, D. 2008. “Urban hierarchy or

local buzz? High-order producer service and (or)

knowledge-intensive business service location in

Canada, 1991-2001”, The Professional Geographer,

60(3), 333-355. DOI: 10.1080/00330120801985661

Steinmueller, W. E. 2002. “Knowledge-based economies

and information and communication technologies”,

International Social Science Journal, 54(171), 141-

153. DOI: 10.1111/1468-2451.00365

Vaishnavi, V., & Kuechler, W. 2004. “Design science

research in information systems”, last updated

September 30, 2011. Retrieved from http://

desrist.org/desrist.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

440