Making Classroom Response Systems More Social

Jonas Vetterick

1

, Bastian Schwennigcke

2

, Andreas Langfeld

2

,

Clemens H. Cap

1

and Wolfgang Sucharowski

2

1

Department of Computer Science, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

2

Department of Humanities, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

Keywords:

Classroom Response Systems, CRS, Live Feedback, Social Learning, Social Communication, Class-wide

Discussion.

Abstract:

Classroom Response Systems (CRS) have been used in the last years to support teachers getting feedback

from their students, especially in lessons with large audiences. Whereas CRS become more and more popular

it is less known how students really use CRS for providing feedback and if social communication on CRS -

and as a consequence in the classroom itself - can increase the benefit of CRS. Our research aims to open the

discussion for more social communication on courses and lessons on CRS-usage by providing grounding of

social communication with CRS. Moreover we outline conceptual and technical insights on an Social CRS

implementation.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is a commonplace that learning success highly de-

pends on the social embedding of learning processes.

Beside motivational or emotional aspects we want to

emphasize, that this embedment can be defined in

terms of communicative interventions into learning

processes. Social embedment of learning allows any

learner to evaluate his or her understanding of given

contents. It even allows to assess the appropriateness

of this understanding through communication with

other learners as well as with teachers and tutorial at-

tendants in different learning contexts. Additionally it

is another commonplace that academic teaching still

often shows a lack of socially embedded learning this

way. Even more, academic teaching misses signifi-

cant strategies to develop this aspect of learning (Lau-

rillard, 2002) (Laurillard, 2012). However, the issue

of how to overcome this state and enable a signifi-

cant social involvement of learning is far less trivial

and still a serious challenge on quality and success of

learning (Masschelein and Simons, 2013).

Classroom Response Systems (CRS) can be re-

garded as a technological reply to this issue. Whereas

the original idea of CRS mainly implements a clicker

functionality, where students answer multiple choice

questions of the teachers (Fies and Marshall, 2006),

they now become a wider platform to provide feed-

back and to elaborate it in direction to a higher social

embedment of learning. Although teachers are still

able to ask multiple choice questions, modern CRS

provide students with the possibility to give more

detailed feedback on demand (Feiten et al., 2012)

(Kundisch et al., 2012).

Whilst modern CRS have been extended with

many features, we think that CRS currently do not

draw on their full potential to support the social em-

bedment of learning. Until know, they are a helpful

tool to link more explicitly the presentation and trans-

mission of content on the teachers side with a specific

range of receptive reactions on the learners side. In

result CRS may support the addressing and solving of

understanding problems.

Moreover, experience with CRS with features be-

yond mere multiple choice tests resulted in partic-

ipants spontaneously inventing new forms of com-

munication. For example, a public chat-like feed-

back channel intended originally to pose questions to

the teacher was used for tutorial-style communication

and for organizing study groups by the students. This

demonstrates a demand for increased social interac-

tion in the classroom.

But at this stage of evolution especially social in-

teractions and communication are neither usefully in-

closed by CRS learning concepts nor documented for

students and teachers further usage on the CRS. In

153

Vetterick J., Schwennigcke B., Langfeld A., Cap C. and Sucharowski W..

Making Classroom Response Systems More Social.

DOI: 10.5220/0004959801530161

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 153-161

ISBN: 978-989-758-020-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

previous work, we recognized a strong need of stu-

dents to communicate with each other on CRS and to

get durable access to the CRS content generated in a

lesson (Vetterick et al., 2014).

Although the social evolution of CRS seems to

be a vital demand as well as an exciting direction of

development, the relation between social interaction

and learning is widely unexplained, especially in the

context of blended and e-learning interventions. This

conceptual paper shall explore this gap in order to bet-

ter estimate social phenomena in the evaluation of ex-

isting CRS and to provide significant constraints for

technological advancements.

This publication describes our position on a cur-

rent learning model, which covers latest and coming

generations of CRS that are aware of social commu-

nication and interaction between students and teach-

ers. Based on this discussion we will elaborate which

aspects of socially embedded learning CRS currently

enable and which aspects are still to be claimed. Fur-

thermore this work outlines how coming CRS should

look and act in order to contribute a serious interven-

tion into the social challenge on learning.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Sec-

tion 2 covers the related work in the field of learning

and feedback and in the field of CRS. In section 3 we

show that there are two different types of communi-

cation on providing feedback. Section 4 presents our

approach for an Social CRS that is aware of and sup-

ports these types. At the end we conclude our work

and outlook future research in section 5.

2 STATE OF THE ART

2.1 Learning and

Communication/Feedback

To ground our investigation on the social embedment

of learning, we want to adopt (this chapter) and par-

tially develop (chapter 3) the learning model, Diana

Laurillard introduced in the late 1990s and has refined

up to her present contributions to the debate on aca-

demic teaching. It promotes our position in a three-

fold way (Laurillard, 1999) (Laurillard, 2002) (Lau-

rillard, 2008) (Laurillard, 2012).

• First, it comes from scientifically based efforts for

reforms in academic education.

• Second, it uses an educational-driven approach to

the use of digital technologies (Laurillard, 2008,

p. 1).

• And third, it implements important aspects of the

social nature of learning.

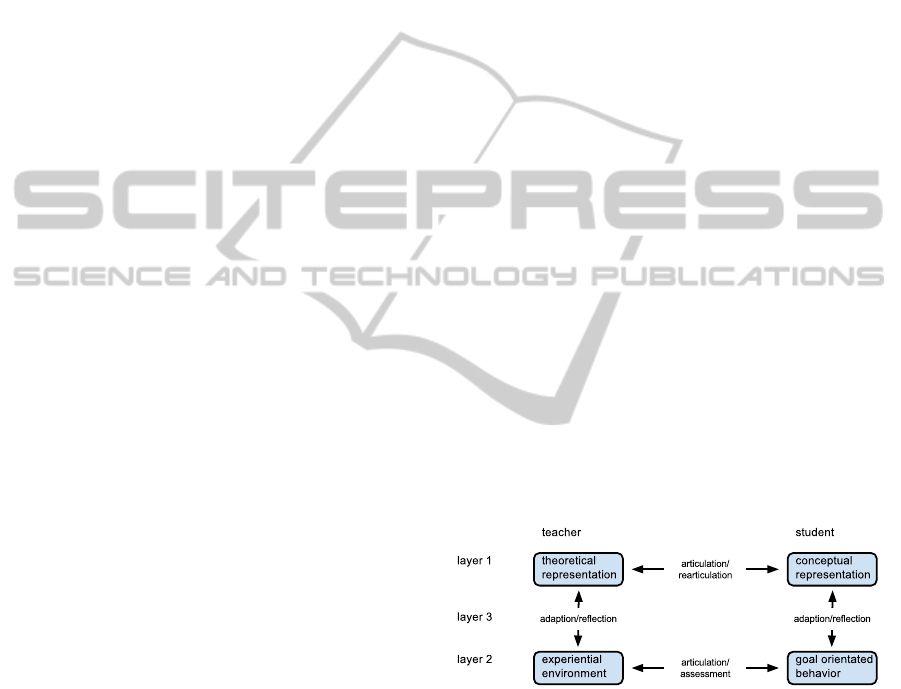

Her model essentially consists of three layers

composed to an conversational framework of learn-

ing (Figure 1). These layers postulate the main func-

tions teachers and learners have in educational set-

tings. The first layer, the layer of conceptual dis-

cussion combines the function of content distribution

on the basis of theoretical conceptions on the teach-

ers side and the function of content documentation

framed by an individual conception on the learners

side. Learners even have to reply on distributed con-

tent and to control their individual understanding of

content in the light of the teachers reactions on their

replies.

The second layer, the layer of interaction, is deter-

mined by a learning environment constituted by the

teacher. Within this environment learners are obli-

gated to solve concrete tasks, such as working out

exercises, solving questions or preparing talks or pa-

pers. Interaction even includes to observe how learn-

ers cope with those tasks on the teachers side. Addi-

tionally, learners will admit their processing of tasks

while teachers attend to and react on their attempts at

a solution.

The third layer establishes a connection between

the first and the second one. It has a meta-cognitive

function and its realization allows to adopt the op-

erations on the interactive layer with respect to the

interchange of content on the conceptual layer. Fur-

thermore it enables to assess the reaches and limits

of theoretical concepts in the light of task coping and

outcomes as practical experiences on the interactive

layer.

Figure 1: Conversational framework of learning (Laurillard,

1999) (Laurillard, 2002) (Laurillard, 2012).

Laurillard claims that learning processes based on

these three layers go beyond simple instruction. Be-

cause any successful understanding of content de-

pends on the ability of teachers and learners to apply a

common ontological (object reference) and epistemic

(direction of understanding) frame of reference. That

means they have to anticipate a common identification

of objects and their epistemic treatment in order to use

transmitted content the same way. However, a central

demand on teaching is not to presume this redundancy

of orientation between teachers and learners, but to

support its evolution. This evolutionary process has to

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

154

take into account an iterative progress of adjustment

between the differing prerequisites of the participants

in an educational process. The core instrument Lau-

rillard suggests to make the outlined adjustment run

is giving and handling feedback on each of the frame-

works layers.

First of all, feedback is a way to interrupt the

progress of content transmission and task instruction

in order to claim a sequence of adjustment between

transmission and reception of content. Normally this

is the case when intentions behind content transmis-

sion on the teachers side and abilities to cope with

content in the intended way on the learners side do not

interlock. Any reaction on feedback has to respond to

that imbalance between intended and performed un-

derstanding more or less extensively. The core is-

sue to compensate this imbalance will be to explore

the individual conditions learners apply to understand

given educational content. This is a common sense

affordance on modern teaching and it means to center

teaching around the learner and provide as much oc-

casions as possible to clear up and integrate the learn-

ers prerequisites within learning processes.

Enabling feedback belongs to a set of ideal solu-

tions to integrate modern, learner centered teaching

into academic education (Weimer, 2013). But there is

a common risk behind those avant-garde demands on

teaching. Admitting feedback contains the problem

to include topics and issues into the learning setting

that could endanger the viability of courses and lec-

tures. Not only genuine spam but also content driven

feedback is able to disturb a lesson significantly. It is

an important challenge to distinguish between feed-

back assimilable to a lesson and feedback that cannot

be integrated. Beside explicit rules or technical fil-

tering, we assume that those decisions are normally

processed by the use of communicative strategies.

2.2 Modern Classroom Response

Systems

As Kay et al stated in (Kay and LeSage, 2009) CRS

have been voting mechanism in the first place: Teach-

ers ask a multiple choice question and students could

answer by clicking the corresponding button on a spe-

cial voting device. As these voting devices are very

expensive and have to be maintained, modern CRS

use the mobile devices students already have. Since

mobile devices, as smartphones, pads or notebooks,

provide a display that can draw more than just buttons

for multiple choice questions, CRS evolve to compre-

hensive feedback systems that are able to implement

more complex forms of feedback (Draper et al., 2002)

(Feiten et al., 2012) (Jenkins, 2007) (Kundisch et al.,

2012) (Vetterick et al., 2013) such as:

• Multiple Choice questions asked by the teachers

(TQ): Teachers can still use modern CRS as click-

ers, but without the limitations of a hardware de-

vice, so they may label their answers or use a flex-

ible number of answers for example.

• Questions from students (SQ): Students ask spe-

cific questions. Other students may vote questions

up or down, which can be an indicator for the im-

portance of questions. Based on the number of

votes the instructor can address the issues in his

lecture. In a variant of this scheme, members of

the audience may reply in writing using the sys-

tem.

• Rating specific presentation parameters (SP): Stu-

dents mark specific issues, for example when the

instructor is moving ahead too fast or the talking

volume is inadequate.

Moreover modern CRS are able to organize the

given feedback to get a deeper understanding. The

following methods present current methods for orga-

nizing live feedback.

• Durable Access (DA): Students and teachers can

later access all the given feedback. Teachers are

then able to provide additional material or exam-

ples and can improve the presentation. Students

can use the feedback to identify important facts,

topic or issues for a better preparation for their

exams (Crouch and Mazur, 2001) (Vetterick et al.,

2014).

• Identify students learning issues across lessons

and terms (LA): By the use of identities (or even

pseudonyms) teachers are able to track down how

students learn. Interested readers are referred to

the field of learning analytics (Ferguson, 2012).

Figure 2 demonstrates how the three forms of

feedback TQ, SQ and SP are organized by DA and

LA. Whilst the feedback generated in a lesson can be

accessed afterwards (DA), LA allows to identify cor-

relations between the students feedback over lessons

or terms.

Figure 2: Interaction of access modes and CRS-features.

Regarding the previously presented interdepen-

dent layers of learning process organization (dis-

cussion layer, interaction layer, layer of adoption

MakingClassroomResponseSystemsMoreSocial

155

and reflection), modern CRS only fit these layers in

parts. The layer of discussion is covered by stu-

dents questions (SQ) and the possibility to rate teach-

ers speech parameters (SP). Students initiate the dis-

cussion about a certain issue or parameter, whereas

teachers have to respond. The layer of interaction is

covered by students questions (SQ), where students

again initiate the feedback by asking questions. Ad-

ditionally the layer of interaction is partly covered

by teachers questions (TQ), because teachers demand

feedback from their students, who then have to in-

teract with their teachers. The layer of adaption and

reflection is partly used by all modern CRS imple-

mentations of TQ, SQ and SP: Students may reflect

their knowledge and understanding on teachers (TQ)

or other students questions (SQ). Moreover teachers

may reflect their teaching to identify facts, topics or

illustrations that are hard to understand for students

(issue repeat offender).

Regarding the methods to organize feedback, LA

and DA cover the layer of adaption and reflection, too.

DA provides persistent access to the content created

by teachers and students during a lesson, so students

are able to reflect their knowledge and understanding

afterwards at any time. Furthermore teachers can do

the same to reflect their teaching. LA allows teachers

to get a deeper knowledge of how students proceed in

their lessons over time (for a whole term for example),

so teachers can reflect their teaching on a wider scope.

3 COMMUNICATIVE LEARNING

3.1 From Feedback to Communication

Chapter two showed that feedback is no add-on but a

core element of learning. Here we want to add that

feedback only works in connection with social, or

rather communicative forms of intervention into the

learning process. Therefore, any elaboration of feed-

back depends on the specific communicative strate-

gies the participants of learning processes are able and

allowed to realize in educational settings. What these

strategies might be, how they work and to what extent

they support learning processes are open questions

within the learning research discussion we presented

above. We consider answers to these questions to be a

significant prerequisite for the evolution of feedback

technologies like CRS.

Communication takes its special role within feed-

back processes, because its main function is not to

discover the full potential of an individuals condi-

tions applied to his or her engagement with trans-

mitted content. That means, communication is more

than just talking about individual states or sensitivi-

ties within learning processes. Communication has to

find a scope of selective topics and issues, which the

communicative partners are able to connect with from

their individual state while they are attending to and

coping with feedback. To treat feedback by commu-

nication means to find a selective way of marking and

negotiating feedback. Selective communicative treat-

ment gives feedback a specific sense and determines

its relevance. We now want to distinguish two major

strategies conveying two basic forms of coping with

feedback in the outlined way (for general introduction

(Baecker, 2009)).

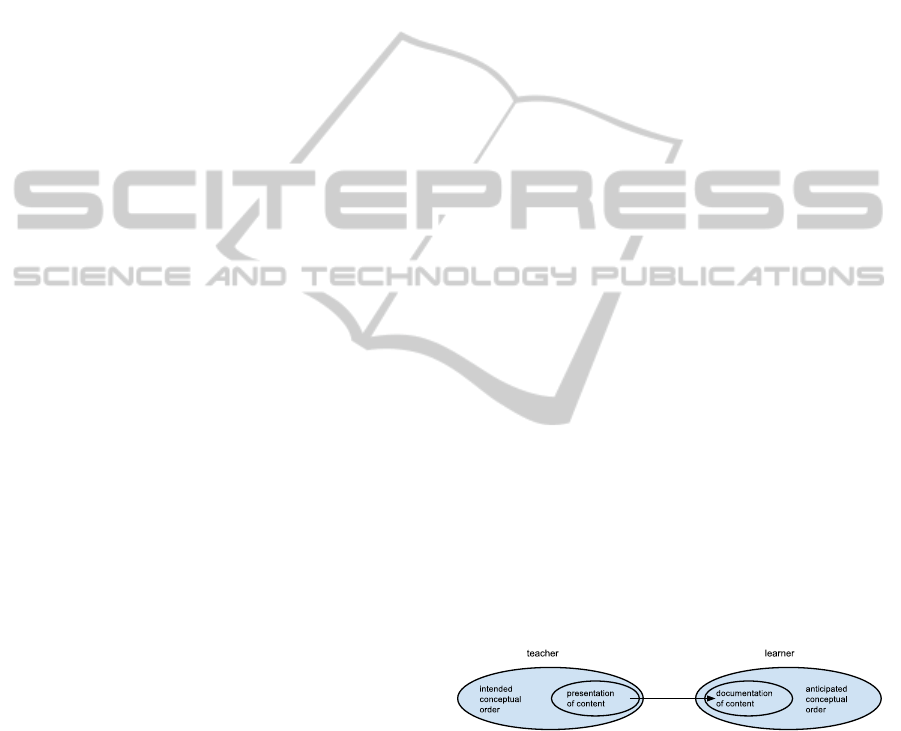

3.2 Systemic Feedback/Communicative

Strategies within Lectures

Lectures normally work on the conceptual layer of

learning. Lectures are successful when learners are

able to anticipate an intended conceptual order of

knowledge out of the way they document presented

content (Figure 3). From a communication the-

ory point of view, this setting could be regarded as

systemic setting. Communicative Systems contain

an affordance-competence balance (Baecker, 2010).

And this is the case, when behavior on the one hand

could be regarded as an accomplishment of an af-

fordance setting on the other. The learners activi-

ties to document content and to anticipate underly-

ing conceptual orders then are accomplishments to

the intentions a teacher has in a specific learning pro-

cess. Feedback framed by a systemic communica-

tion strategy will focus the partners on their knowl-

edge about the structure of demands within that set-

ting. They have to specify and reformulate what they

determine to be the right understanding of underlying

affordances.

Figure 3: Conceptual basis of learning based on (Laurillard,

2002) (Laurillard, 2012).

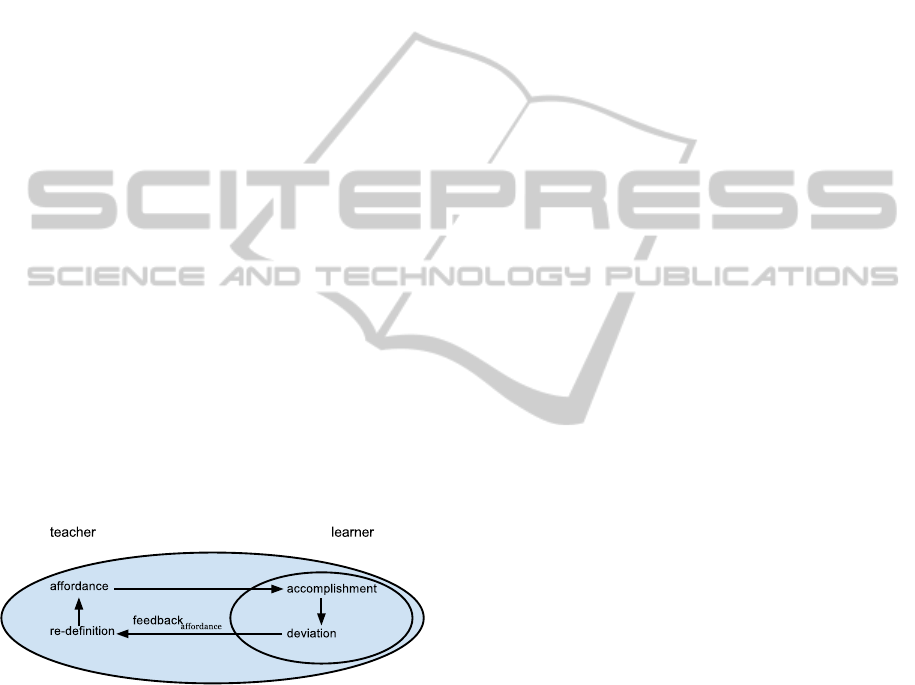

In result the partners are able to decide whether

their behavior is a deviation reclaimable by an accom-

plishment that fits to their understanding of given de-

mands. Reaction on feedback within this framework

will take feedback as a hint on deviation from ideal

and it will reclaim this ideal by re-defining the affor-

dance structure behavior should apply to. The prob-

lem is, such communicative framework only deals

with feedback allowing to connect deviating behavior

with redefinitions of given affordances. That means,

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

156

feedback already has to contain certain links to that

affordance structure. In other words, it has to be con-

sciously settled within a given affordance framework,

which is shared between the communicative partners

in the feedback process.

For example students ask for more explanation

within a given topic area because they understand this

topic area to be important for their exams and fear to

overlook important issues without more explanation.

However requesting more explanation could be a de-

viation from ideal learner performance within a lec-

ture. But it could be handled within the systemic strat-

egy, if the students request already contains knowl-

edge about an intended affordance on the teachers

side, e.g. exam preparation, and if this knowledge is

shared between teacher and student. Replies to this

feedback only have to redefine the affordance struc-

ture exam preparation in order to adjust performed

and ideal behavior, that means to decide whether re-

questing more explanation is useful or not within the

affordance set exam preparation.

We call feedback annotated in Figure 4 affordance

competent or systemic feedback. We want to sug-

gest that it only can be given by skilled students with

enough experience within specific educational set-

tings as university lectures or courses. It only works if

feedback is applied to students assumptions on possi-

ble affordance structures or more general if feedback

can be treated this way. Treating feedback within a

systemic strategy needs communicative partners, who

are able to find and assume comparable assumptions

on a set of affordances in a learning process.

Figure 4: Systemic feedback process (integrated application

of (Baecker, 2010) and (Laurillard, 2002)).

3.3 Concept Critical Interventions into

Feedback

Feedback without a strong linkage to socially shared

affordances is difficult to handle within a systemic

framework. This is a significant problem for learn-

ing processes. Because this more open type of feed-

back contains the highest potential to enable and de-

velop learning advancements (Bateson, 2000). Be-

cause deviation from pre-defined sets of learning af-

fordances allows to go beyond affordance sets and to

understand their constitution and justification within

broader conceptual considerations (Baecker, 2008)

(Baecker, 2012) (White, 2012). If we go back to our

little example of exam preparation it makes a signif-

icant difference whether students understand how to

apply lecture contents to exam affordances or they

understand, that exam affordances are constituted in

the context of different and sometimes even com-

peting standards within scientific paradigms or even

other perhaps administrative and legal considerations.

Feedback that deviates from pre-defined affordance

sets contains the opportunity to investigate such con-

texts and to reclaim a deeper understanding of learn-

ing affordances and their range of variation .

The learning theory discussion above suggested

to realize such demands by switching between dif-

ferent learning layers and to transfer experiences on

one layer to the other. It has been emphasized that

such transfer allows to insert experiences on one layer

as a hint on the conceptual basis, that constitutes the

other layer. For example the quizzes function of CRS

can be used to go through a kind of exam like situ-

ation in order to help students anticipating the exam

affordance set behind lectures. However the main is-

sue here is, that this conclusion has to be worked out

in a broader communicative setting. Within this set-

ting communication has to ensure, that deviations are

not rejected too soon as interferences into pre-defined

systemic frameworks. Instead communication has to

be aligned to find contexts which handle systemically

deviating feedback as occasion to search for other

affordance-accomplishment balances or as occasion

to adapt pre-defined affordances.

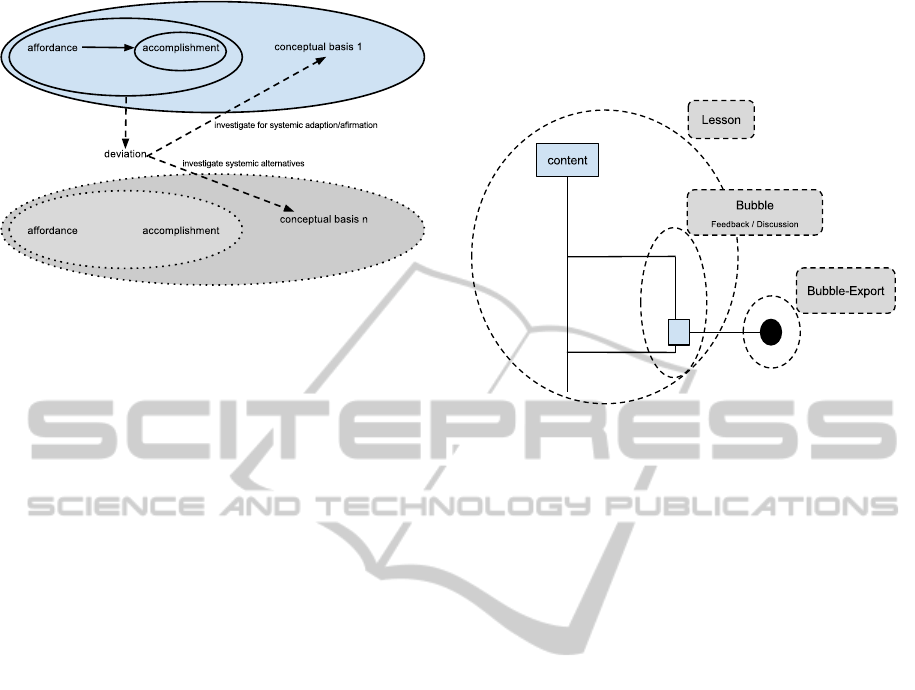

On a communicative level it also means to find

different partners or groups, who are able to pick up

and investigate feedback in the outlined way. In ef-

fect, this type of communication leads to adaptive

processes within given systemic frameworks as well

as to distinction and differentiation between varieties

of systemic settings. This type of communication ad-

ditionally unfolds demands on the comparative com-

petences amongst communicative partners. And this

demand has to be implemented by parallel investiga-

tions into the conceptual basis different systemic set-

tings are based on (Figure 5).

This type of communicative intervention allows

to rebind deviations from single affordance settings

back into academic lessons and to apply the content

and the progress of lessons to different scopes of rele-

vance and function. In effect, the communicative de-

mands on such intervention are more complex. Be-

cause given feedback could not only be immediately

applied or rejected, but even preserved for later treat-

ment, transferred into other contexts of application

MakingClassroomResponseSystemsMoreSocial

157

Figure 5: Concept critical intervention into feedback.

and integrated into social discourse about the range

of conceptual diversity feedback fits to.

4 SOCIAL CLASSROOM

RESPONSE SYSTEMS

Based on the critics and the suggestions for improve-

ment from chapter 3, we will outline a new generation

of CRS that is aware of and supports communicative

intervention into feedback. The notion of classroom,

however, has to be understood in the broader sense of

a community of learners; their interaction may occur

at the same time and same place (traditional CRS) or

at different places (for remote learners) or times (car-

ried over to different cohorts of learners).

This section describes our approach for a social

CRS that is aware of social communication. At first

we will present the conceptual design for this ap-

proach, then we address technical challenges and state

feasible implementations for them.

4.1 Conceptual Design

On feedback-events (communicative interventions),

when students struggle with an issue, discussions with

others can arise. CRS should be aware of these

events, because they are a part of students learning

process. Similar to bubbles that rise to the surface,

discussions can split off the lessons content. Whether

or not discussions may not directly related to the

lessons content, they are important for their mem-

bers and can become interesting later on. Moreover,

CRS should provide methods to initiate or create such

discussion-bubbles. Because students often use their

own medium, as social networks or online learning

platforms, to discuss an issue, CRS should be able to

export discussions. Thereby students are still able to

use their known medium for discussion even if they

deal with something that has not been created on this

medium (enabling concept critical feedback). Figure

6 illustrates this concept.

Figure 6: Discussion initiated during a lesson and their pos-

sibility for usage in external environments.

In addition to the ability to leave lessons to fol-

low a discussion, CRS have to provide a mechanism

to return to a lecture, so students on the one hand can

adapt their knowledge generated from the discussion

to the current teaching content and teachers on the

other hand can react on issues aftereffects. CRS that

support to leave to and return from a discussion to

a lesson are then able to keep track of learning pro-

cesses. This enables teachers and students to orga-

nize and analyze their own and others learning pro-

cesses. Furthermore a lecture does now not only con-

sist of teachers knowledge-materials, it also consists

of the process how students identify and solve issues

on lessons knowledge itself and on teachers learning-

materials (adopt systemic affordances and investigate

alternatives according to chapter 3.3, Figure 6).

Whereas traditional technical support in a class-

room started with a blackboard and evolved via pro-

jector to an electronic presentation of learning mate-

rial. The next logical step is interactive learning ma-

terial, where the interaction can take place with a pre-

programmed digital tutor (systemic intervention), or

with a human docent or co-learner (systemic and con-

cept critical intervention). This communication how-

ever must not have the usual digital form of interper-

sonal exchange (such as email, forum etc.) since in

this form it is not centered on the topic to be learned

or on the learner but rather on the usual human rit-

ual of communication. Rather, new forms of dynamic

lecture materials should be developed, where a Q&A

session with a docent of a co-learner is directly con-

nected with that place in the lecture material, where

the problem arose.

Filtering of content, when a participant is able to

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

158

select the information he will see, and targeting of

content, when a participant is able to designate recip-

ients for his questions, remarks and answers, might

be necessary to maintain a reasonable signal-to-noise

ratio on a social CRS. This is especially important,

when the collection and dissemination of contribu-

tions is not restricted to real time classroom activities

and may span even courses.

4.2 Technical Design

Regarding the concepts previously described there are

many technical challenges for implementations of So-

cial CRS. Because modern CRS clients mostly run

on mobile devices we assume that every potential

user has a web browser and an internet connection,

whether mobile or not. Based on this assumption we

identify three main technical challenges. First of all

there is the teaching content itself, which is the source

of most feedback and the main part of interactive

learning materials. Second the discussions, including

their participants, references and verbalisations have

to be implemented. Third the export of discussions is

a functionality that highly depends on other technical

frameworks, concepts and standards.

The teaching content mainly covers teachers pre-

sentation slides, scripts or any other digital docu-

ments. Current web technologies are able to present

and distribute all of these documents, so the previous

assumptions of an existing web browser enables So-

cial CRS to display nearly every digital content teach-

ers are currently using.

Providing a space for discussion or social commu-

nication is mainly covered by feedback type SQ (stu-

dents questions). Even so discussions can arise from

issues on other feedback types, so there has to be an

implementation to switch to SQ or at least to initiate

a discussion on a different medium. Furthermore dis-

cussions can include references to the teaching con-

tent, which can be implemented with references to

digital objects (pictures, paragraphs, words, videos,

etc.) of the digital teaching content. Moreover, so-

cial communication needs participants who can be ad-

dressable and identifiable. Modern CRS mostly have

possibilities for users to use an existing identity, either

from their university software system or their social

networks. At least all users should be able to address

new participants for a discussion and to resign the par-

ticipation in a discussion. Social CRS can implement

this requirement by using the existing identity man-

agement.

Exporting discussion or social communication

highly depends on targets for an export and needs a

specification for addressing. As stated above we rec-

ommend a strategy where digital fragments (or dig-

ital objects), as paragraphs, slides, pictures, etc, get

unique identifiers. Additionally we assign each dis-

cussion and each point of discussion an unique id.

Over the set of all digital objects and their identifiers

Social CRS can span an Application Programming

Interface (API), so identifiers are accessible with an

unique URL. Thus Social CRS create the ability for

an ecosystem around the given feedback. Applica-

tions of this ecosystem are able to access all the digital

objects even if they were not created on them.

5 CONCLUSION

Our conclusion is that there is a strong need for CRS

to allow and support social communication in learn-

ing environments. We showed that there are two basic

types of communication on providing feedback. On

the one hand the systemic intervention into feedback,

when students need to deviate their accomplishment

due to differences between their understanding and

teachers knowledge. On the other hand the concept

critical intervention onto feedback, which allows to

rebind deviations from an affordance settings and to

apply the teaching content and the progress of lessons

to different scopes of relevance and function.

Moreover we presented conceptual and technical

designs to create a Social CRS that is aware of these

types of social communication (of feedback). This

includes our approach to handle discussions (commu-

nicative interventions), which result from feedback,

as important and necessary. CRS should allow to ini-

tiate or create discussions as a new part of a lesson

that may be progressed in a different medium as well

as CRS have to provide a way back to the teaching

content. In addition we presented technical solutions

for this concept which mainly base on a web applica-

tion that provides discussion-objects.

In fact of the importance of discussions we are

sensible of the distractions Social CRS will create.

We see (Social) CRS as a tool for teachers and stu-

dents that can support the learning process. For this

reason one has to be aware that CRS are only able to

see a portion of reality. This means that the benefit of

feedback and its permanently availability highly de-

pends on students motivation to document their feed-

back.

Beside this limitation Social CRS and CRS in gen-

eral are able to become more than just feedback sys-

tems. In practice we observed students using CRS

to criticize also the system around the lecturer: Some

students claimed nuisances on the composition of stu-

dents with different states of knowledge, which is

MakingClassroomResponseSystemsMoreSocial

159

because the students come from different areas and

which is enforced by the university administration.

Even if the lecturer recognized this critics as spam at

first, he identified it as this critic later on. Keeping this

in mind makes it hard to decide if a discussion’s level

of distraction is worth it or not, even if this discussion

might look like spam.

Further research should take up the discussion

about social communication with CRS in general.

Moreover there are several interesting questions on

the discussion export. For example if it is possible to

remove an existing export or all related connections.

Furthermore it is possible that the ability to document

all the social communication can lead to more unre-

lated information, such as spam, and that such infor-

mation result in more expense of filtering them. In

addition to this question further research can focus on

the filtering itself. The filtering itself can be a part of

the learning process and may be underestimated.

At least studies on CRS usage are highly impor-

tant. On the one hand it has to be evaluated how

teachers and students use Social CRS and if they get

an benefit from them. On the other hand it should be

evaluated when students use Social CRS or their doc-

umented content respectively. The latter may show

that students use their documented social communica-

tion mostly for preparation for their exams. Of course

this hypothesis is speculative at this point, but such

an offline use, however, could require coining a new

term, since it no longer is a Classroom Response Sys-

tem.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the German Fed-

eral Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and

the University of Rostock. We gratefully acknowl-

edge the professional and motivating atmosphere of-

fered by them in supporting our study. We thank M.

Garbe for discussions and comments on this topic.

REFERENCES

Baecker, D. (2008). The network synthesis of social action

ii: Understanding catjects. Cybernetics and Human

Knowing, 15(1):45–65.

Baecker, D. (2009). Systems, network, and culture. Soziale

Systeme, 15:271–287.

Baecker, D. (2010). A systems primer on universities.

Soziale Systeme, 16:356–367.

Baecker, D. (2012). Observing networks: A note on asym-

metrical social forms. Cybernetics and Human Know-

ing, 19(4):9–25.

Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected

essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution and

epistemology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago,

5 edition.

Crouch, C. H. and Mazur, E. (2001). Peer instruction: Ten

years of experience and results. American Journal of

Physics, 69:970.

Draper, S., Cargill, J., and Cutts, Q. (2002). Electronically

enhanced classroom interaction. Australian journal of

educational technology, 18(1):13–23.

Feiten, L., Buehrer, M., Sester, S., and Becker, B.

(2012). Smile-smartphones in lectures-initiating a

smartphone-based audience response system as a stu-

dent project. In CSEDU (1), pages 288–293.

Ferguson, R. (2012). The state of learning analytics in 2012:

A review and future challenges. Knowledge Media

Institute, Technical Report KMI-2012-01.

Fies, C. and Marshall, J. (2006). Classroom response sys-

tems: A review of the literature. Journal of Science

Education and Technology, 15(1):101–109.

Jenkins, A. (2007). Technique and technology: Electronic

voting systems in an english literature lecture. Peda-

gogy, 7(3):526–533.

Kay, R. H. and LeSage, A. (2009). Examining the benefits

and challenges of using audience response systems:

A review of the literature. Computers & Education,

53(3):819–827.

Kundisch, D., Sievers, M., Zoyke, A., Herrmann, P., Whit-

taker, M., Beutner, M., Fels, G., and Magenheim, J.

(2012). Designing a web-based application to support

peer instruction for very large groups. International

Conference on Information Systems 2012.

Laurillard, D. (1999). A conversational framework for indi-

vidual learning applied to the ’learning organisation’

and the ’learning society’. Systems research and be-

havioral science, 16(2):113–122.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: A

framework for the effective use of learning technolo-

gies. RoutledgeFalmer, London, 2 edition.

Laurillard, D. (2008). Digital Technologies and Their Role

in Achieving Our Ambitions for Education. ERIC.

ISBN 978-0-8547-3797-0.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science: Build-

ing Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technol-

ogy. Routledge, New York.

Masschelein, J. and Simons, M. (2013). The university

in the ears of its students: On the power, architec-

ture and technology of university lectures. In Ricken,

N., Koller, H.-C., and Keiner, E., editors, Die Idee

der Universit

¨

at - revisited, pages 173–192. Springer

Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden.

Vetterick, J., Garbe, M., and Cap, C. H. (2013). Tweed-

back: A live feedback system for large audiences. In

5th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU2013).

Vetterick, J., Garbe, M., Daehn, A., and Cap, C. H. (2014).

Classroom response systems in the wild: Technical

and non-technical observations. International Journal

of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 8(1):21–25.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

160

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key

Changes to Practice. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2

edition.

White, H. C. (2012). Identity and Control: How Social For-

mations Emerge. Princeton University Press, Prince-

ton, 2 edition.

MakingClassroomResponseSystemsMoreSocial

161