Using Activity Theory in Developing Instructial Tools for

Project Management Studies

Maritta Pirhonen

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Keywords: Project-based Learning, Project Management Education, Activity Theory, Supervising, Instruction.

Abstract: Competence and skills of the project manager are significant to project success. The skills needed in project

managers’ work cannot be learned only by reading the books or a lecture hall; one learns them by practice.

Therefore, an important challenge for educational institutions is to develop pedagogical practices that allow

students to participate in working life projects and to confront real-life problems. Project-based learning

(PBL) offers a model that enables students to practice the skills and competences needed in working life

projects by utilizing real-world work assignments in time-limited projects. Using PBL method alone does

not necessarily guarantee learning result. In order to be successful, PBL method requires effective and

competent supervision and guidance of students as well as appropriate tools for instruction. In this study the

concepts from activity theory (AT) are applied to development tools for supervising project-based learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

The connection between project manager’s skills

and project success has been addressed in several

studies (Iacovou and Dexter, 2004); (Müller and

Turner, 2007). Often these skills are learnt in real-

life working situations, because acquiring skills

necessitates experience instead of studying

theoretical facts by reading a book, or attending a

lecture. Learning necessary soft skills required in IS

project management and leadership during the

project studies might support IS projects succeeding

in "real world" working scenarios. Therefore, project

management education needs to focus on practical

issues of managing rather than on tools and

techniques of management itself.

Project-based learning (PBL) offers a model for

students to practice the skills and competences

needed in IS projects by utilizing real world work

assignments in time-limited projects (Tynjälä et al.,

2009). However, using PBL method alone does not

guarantee learning results. In order to be successful,

PBL method requires both effective and competent

supervision and an uniform learning environment

that enables easy access and use of online materials.

The goal of the research in progress is to develop

pedagogic methods and tools to support the learning

of skills and competencies required in IS project

work. Activity Theory (AT) concepts provide an

analytical framework for developing the

instructional methods responding to the educational

needs. Particularly the concept of contradiction

(“historically accumulating structural tensions

within and between activity systems” (Engeström,

2001, p. 137) is seen to provide rich and fruitful

insights into the system dynamics.

This paper is organized as follows. First, we

depict the course, which is based on the project-

based learning approach. Second, pedagogical

background for project-based learning is reviewed.

In the following chapter brief description of activity

theory is presented. This is followed by the

description of the project management course as an

activity in AT. Finally, an outline of our ongoing

research is presented.

2 PROJECT MANAGEMENT

COURSE

The project-based learning (PBL) approach has been

adopted in information system education at the

University of Jyväskylä for years (see more

Pirhonen 2009, 2010). For example, the

implementation of the Project Management and

Execution (PME) course (10 ECTS credits) is based

323

Pirhonen M..

Using Activity Theory in Developing Instructial Tools for Project Management Studies.

DOI: 10.5220/0004963203230328

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 323-328

ISBN: 978-989-758-021-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

on PBL approaches (Tynjälä et al., 2009). The

course belongs to the elective studies towards the

degree of Master of Economic Sciences in the field

of ICT. The main aim of the PME course is to offer

the students an opportunity to gain authentic

practical experience of an ICT experts’ work. In

addition, the goal is to provide students with a

comprehensive and a realistic view of the work in IS

projects. In more detail, students are expected to

learn project management, leadership, group work,

and communication by managing, leading and

executing information systems projects. In addition,

they are expected to learn an assessment of the

significance of team leading as a part of project

success.

The learning environment is maintained in co-

ordination with three parties – a student group, the

university, and a client organization. A legally

binding cooperation contract is drawn up between

the three parties before project starts. It covers the

subject matter (a description of the project

objectives), the obligations and rights of the

contracting parties, copyrights, guarantees and

maintenance, confidentiality and the concealment of

confidential information, payments and the payment

schedule.

The project course lasts from the beginning of

November to the end of April (26 weeks). During

the course each student is expected to use 140 hours

for implementing the project task and 130 hours for

demonstrating project-work skills, including team

leading, group work, and communication. The

groups plan their work, complete the scheduled

tasks, and produce deliverables. Each student is

expected to take the role of project manager and

project secretary. These roles rotate every month to

ensure that each member of the project team works

in both roles at least once. In total, a group of five

students uses 700 hours in planning and executing

the client project.

During the course, students work in close co-

operation with their client and they meet with the

client representatives on weekly basis. In addition,

the guest lectures from collaborative companies are

invited to give lectures on relevant topics to project

management. The collaboration with a client ends in

a steering group meeting at which the results of the

project are approved.

During the course seminars are arranged to

enhance students´ communications skills..

Pedagogical activities such as peer reviewing, group

discussion, peer coaching and self/peer assessment

are being set up by supervisors to enhance the

learning effectiveness of the project.

Each student group is evaluated twice during the

six-month period of the project. The first evaluation

takes place in the middle of February after three

months’ work. The second evaluation is carried out

at the end of the course in April. The content of the

evaluation is grouped and structured around the

themes covering issues to the course’s learning

objectives and critical to project management

success. The course grade (1-5) for a group is

calculated on the basis of the following factors:

project management, project work, and

communication. The evaluation involves composing

an evaluation report using the assessment

framework. Both students and their supervisors

compose the report. Written evaluations are

uploaded in the digital learning environment Optima

(the day before an evaluation discussion). The

evaluation is based on the perceptions of the

students´ work capabilities with their clients as well

as the documentation produced during the project.

Both supervisors and the student groups are

acquainted with the each other’s evaluations before

an evaluation discussion. The grading of the course

is mainly based on the debates that emerge during

discussions concerning the reports.

3 PROJECT-BASED LEARNING

Problem-Based Learning (PBL – nowadays also the

abbreviation for Project-Based Learning) has

become widely recognized over the last 40 years.

PBL has been proven to be successful educational

approach in many different study domains. It has

been adopted for years in Aalborg University in

Denmark (Graaff and Kolmos, 2003). According to

Kjersdam (1994) students graduated from Aalborg

are more productive and competent compared to

graduated students from other educational

institutions.

Project-based learning (PBL) refers to a theory

and practice of utilizing real-world work

assignments on time-limited projects to achieve

mandated performance objectives and to facilitate

individual and collective learning (Smith and Dods,

1997). The theory of PBL is based on constructivism

and according to the constructivism theory, the

learner is guided to build and modify his or her

existing mental model. This means that the focus is

on knowledge construction rather than on

knowledge transmission as in the theory of

behaviourism. Constructivism takes account of the

situational nature of learning and thus advocates

authentic or simulated environments (von

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

324

Glasersfeld 1984). There are five significant features

of PBL (Helle, Tynjälä, Lonka and Olkinuora 2007):

• a problem or a question serves to drive learn-ing

objectives;

• a concrete artifact is constructed;

• the learners control the learning process (pacing,

sequencing, and actual content);

• the learning is contextualized (what we learn in a

particular context we recall in similar contexts);

and

• projects are complex enough to induce students

to generate questions of their own.

In many models of project-based learning, students

are assumed to work on real world projects by

default. This creates good conditions to learn a vast

range of skills in various project areas. Students

learn management, teamwork, and communications,

as it involves both individual and co-operative

activities, interactive discussions and writing in the

form of plans, reports, memos etc. This type of

learning offers a very concrete and holistic

experience of certain processes such as the process

of construction work or managing a project (Helle et

al., 2006). Often collaboration skills are put into

action by the collaborative nature of project

management. In fact, the studies have suggested that

project work may have many educational and social

benefits (Moses et al., 2000), such as the

development of communication skills (Pigford,

1992), along with team-building and inter-personal

skills (Roberts, 2000). Supervisors support the work

of their students by guiding and assisting them to

learn independently and helping them to retrieve

relevant information when required. Supervisors

oversee the project process and monitor the progress

and performance of each student. The role of the

supervisor is vital, especially in the early stages of

the project when students may need more guidance

in situations where they need to communicate and

collaborate with their client.

4 ACTIVITY THEORY – AN

OVERVIEW

Activity theory (AT) offers a theoretical framework

to study both individual and collective activities. It

provides an analytical framework within which to

study human activity in general. A model of the

structure of an activity system (AS) includes two

types of constituents: core components, such as

subject, object/outcome, and community; and

mediatory components, such as instruments (tools),

rules, and division of labor (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The structure of a human activity (adapted from

Engeström, 1987, p. 78).

An activity is a collective phenomenon; it has a

subject (an individual or collective) who understand

its motive, and who uses tools to achieve an object,

thus transforming objects into outcomes. An activity

is always associated with long-term purposes and

strong motives. All members of the community

share the object (and the motive) of the activity.

Tools mediate between a subject and the object,

which is transformed into the outcome. The object is

seen and manipulated within the limitations set by

the tools. Rules mediate the relationship between the

community and the subject, while the division of

labor mediates the relationship between the

community and the object. Rules cover both implicit

and explicit norms, conventions, and social relations

in a community as related to the transformation

process of the object into an outcome. The

responsibilities of the members of the community

are coordinated by some division of labor (e.g., the

division of tasks and roles among members of the

community and the divisions of power and status),

yet guided by rules. These rules regulate, as well as

constrain, their actions and relationships in the

activity system (Engeström, 1990; Kuutti, 1996).

Engeström (1987) added the concept of

contradiction onto Vygostky´s (1978) thinking.

Primary contradictions are those found within a

constituent of the activity (i.e., in the object, rules,

tools, etc.) and secondary contradictions are those

that appear between constituents of the activity (e.g.,

between the tool and the subject). Contradictions

constitute a key principle in AT and shape an

activity (Engeström, 2001). When contradictions

arise, or when they are observed, they expose

dynamics, inefficiencies, and importantly,

opportunities for a change (Helle, 2000). Kuutti

(1996, p. 34) describes contradictions as “a misfit

within elements, between them, between different

Instruments

Object

Rules

Subject

Community Division of

l

a

bour

Outcome

Transformation

Motivation

UsingActivityTheoryinDevelopingInstructialToolsforProjectManagementStudies

325

activities, or between different development phases

of a single activity”. They generate “disturbances

and conflicts, but also innovative attempts to change

the activity” (Engeström, 2001, p. 134).

Contradictions are significant for development

and they exist in the form of resistance to achieving

goals of the intended activity. They also exist as

emerging dilemmas, disturbances, and

discoordinations. In spite of the potential of

contradictions to result in development in an activity

system, the development does not always occur.

Often contradictions may not be easily recognized or

acknowledged, visible, or even openly discussed by

those experiencing them (Engeström, 2001). On the

other hand, contradictions that are not discussed may

be embarrassing, or uncomfortable in nature. They

may also be culturally difficult to confront, such as

personal habits, bad behaviour, or an incompetence

of the leader.

To summarize, subjects, who are motivated by

an object, carry out activities. A subject transforms

the object into an outcome. An object may be shared

by a community of people, working together to

achieve a desired outcome. Tools, rules, and a

division of labor mediate the relationship between

the subjects, community, and the object.

Contradictions are a key principle in AT and they

are driving force of change.

5 PROJECT MANAGEMENT

COURSE AS AN ACTIVITY

In the depiction of PME course as an activity

system, a student group is chosen to be subject. A

subject plays a key role when analysing other

elements of an activity. In this case we are interested

in student group´s perspective – how the tools

support their learning and achieving the course’s

learning objectives - when analysing PME activity.

The objectives of the cooperation parties differ.

From the students’ and supervisors’ points of view,

the main object is to learn useful skills needed in

“real project work”. Correspondingly clients’ main

motive to co-operate with the university and by

doing so, find potential employees to recruit.

Certainly, clients’ objective is also to obtain results

from the project they are involved with. This is a

goal they naturally share with the students they have

worked with. Different types of objectives, however,

might cause contradictions between the parties

involved. If such an event occurs, the supervisors

need to intervene in the situation by discussing

openly about the issue with all parties. In our study

we focus on the objective seen from the point of

student group´s view. Their motive is to achieve the

course’s learning objectives. The outcome of course

of is that students are provided with skills needed in

projects. The activity “PME course” is presented in

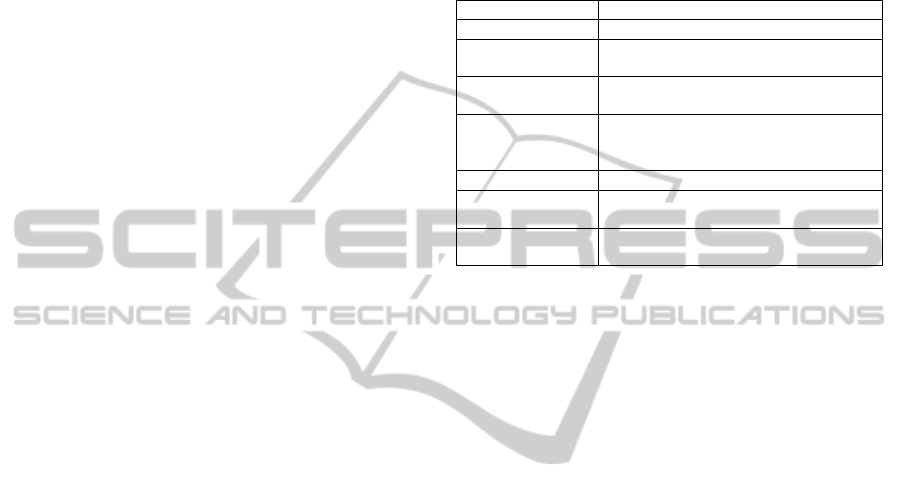

the terms of activity theory (AT) in Table 1.

Table 1: PME course as an activity.

5 Description

Subject Student group

Object

To learn skills needed in project

management

Outcome

To enable students to develop skills

needed in project

Instruments or

tools

Project management tools,

communication tools, guiding meetings,

written instructions, pedagogic methods

Community Students, teachers, clients

Division of labour

Responsibilities according to the

contract

Rules

Constraints on schedule, contract,

assessment

The tools include a project management system

(e.g. software, standards), weekly meetings between

the supervisor and the student group, and written

instruction. During the meetings, the weekly project

reports and project plans are discussed and

reviewed. The project manager and team members

keep providing updates of their project, which are

compared with the documented expectations in the

project plan.

The present tools are seen to have troublesome

features. First, the amount of the tools required in

the project work is great, and they are located in

several, different environments. Project management

tools (e.g. software for managing the schedule or the

resources) are located in multiple systems and data

transmission between systems has been proven to be

difficult and time-consuming. Second, the written

instructions are stored in the digital learning

environment into which students need to log in

separately in order to gain access to project

documentation, or upload and share new documents.

Students are frustrated while working with so many

incompatible systems, which may even decrease

their motivation to study.

Activity theory emphasizes that a tool should

come fully into being when it is used and that

knowing how to use it is a crucial part of the tool.

Therefore, the use of tools entails an evolutionary

accumulation and transmission of social knowledge,

which influences not only the external behaviour but

also the mental functioning of individuals.

Therefore, the pedagogic tools supporting and

promoting learning are vital part of supervisors work

with their students.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

326

6 CONCLUSIONS

Effective and competent supervision and guidance

of students is a vital part of a project-based learning

method; PBL method alone does not guarantee

learning results. Hence, appropriate pedagogic

instructional tools and methods are of critical

importance of achieving learning goals.

To understand the underlying contradictions

between a student group and tools used in project

studies, we adopt the activity theory (AT) as our lens

to explore possible misfits. The strength of AT is

that it allows to break down the structure of an

activity into smaller categorical elements

(Basharina, 2007), and to identify contradictions and

structural tensions of the activity (Engeström, 1995);

(Engeström, 2001). Contradictions relate to

tendencies or forces that need each other, but at the

same time negate each other. The contradictions

generate disturbances, conflicts, and eruptions in an

activity, thus making contradictions indirectly

visible. By recognising structural tensions that

causes disturbances and conflicts in activity it is

possible that new forms and qualitative stages of

activity emerge as solutions to the contradictions

(Engeström, 1987). This being the case, we argue

that the AT provides us with the proper theoretical

lens to develop instructional tools for project

management studies at the University of Jyväskylä.

So far we have modelled the PME course as an

activity system. Next step in our study is to start an

exploratory study by interviewing students,

supervisors, and clients having participated in the

PME course in 2011 - 2014. The aim of the study in

progress is to identify the disturbances emerged

during the course and contradictions that cause

“problems, ruptures, breakdowns, and clashes”

(Kuutti, 1996, p. 34). In this phase of the study we

are especially focusing on contradictions found

between the student group (subject) and pedagogic

methods and tools used during the course. Further

studies may also benefit from a deeper investigation

of the objectives of the PME course from clients’

points of view for purposes to find contradictions

between different objectives of the cooperation

parties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Eliisa Jauhiainen and Minna

Silvennoinen their insightful feedback in the

development of this study.

REFERENCES

Basharina, O. K. 2007. An activity theory perspective on

student-reported contradictions in international tele-

collaboration. Language Learning & Technology,

11(2), 82-103.

Cole, M. and Engeström, Y. 1993. A cultural-historical

approach to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (Ed.)

Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational

considerations. Cambridge University Press, New

York.

Engeström, Y. 1987. Learning by expanding: An activity-

theoretical approach to developmental research.

Helsinki: Orienta-konsultit.

Engeström, Y. 1990. Learning, working, and imagining:

Twelve studies in activity theory. Helsinki: Orienta-

konsultit.

Engeström, Y., 1995. Objects, contradictions and

collaboration in medical cognition: an activity-

theoretical perspective. Artificial Intelligence in

Medicine, 7 (5), 395-412.

Engeström, Y., 2001. Expansive learning at work: towards

an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of

Education and Work, 14(1), 133-156.

de Graaff E. and Kolmos, A., 2003. Characteristics of

problem-based learning, International Journal of

Engineering Education, 19(5), 657–662.

Helle, M. 2000. Disturbances and Contradictions as Tools

for Understanding Work in the Newsroom, Scandina-

vian Journal of Information Systems, 12(1), 81-113.

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P. and Olkinuora, E. 2006. Project-

based learning in post-secondary education – theory,

practice and rubber sling shots. Higher Education,

51(2), 287–314.

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P., Olkinuora, E. and Lonka K. 2007.

’Ain’t nothing like a real thing’. Motivation and study

processes on work-based project course in information

systems design. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 77(2), 397-411.

Iacovou, C. L. and Dexter, A. S. 2004. Turning around

runaway information technology projects. California

Management Review, 46(4), 68-88.

Kjersdam, F. 1994. Tomorrow´s Engineering Education –

The Aalborg Experiment. Journal of Engineering

Education, 19(2), 197-204.

Kuutti, K. 1996. Activity Theory as a potential framework

for human-computer interaction research. In B. Nardi

(ed.) Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and

Human Computer Interaction, MIT Press, Cambridge,

17-44.

Moses, L., Fincher, S., Caristi J., 2000. Teams work (panel

session) in Haller S. (ed.) Proceedings of the thirty-

first SIGCSE technical symposium on Computer

science education, March 7-12. Austin, USA. New

York: ACM Press, pp. 421-422.

Müller, R. and Turner J. R. 2007. Matching the project

manager’s leadership style to project type.

International Journal of Project Management, 25(1),

21-32.

Pigford, D. V., 1992. The Documentation and Evaluation

UsingActivityTheoryinDevelopingInstructialToolsforProjectManagementStudies

327

of Team-Oriented Database Projects. Proceedings of

the twenty-third technical symposium on Computer

science education, Kansas City, Missouri, United

States. New York: ACM Press, pp. 28-33.

Pirhonen, M. 2009. Challenges of Supervising Student

Projects in Collaboration with Authentic Clients. Pro-

ceedings of the 1st International Conference on Com-

puter Supported Education (CSEDU) [CD-ROM],

Lisbon, Portugal, May 23-26, 2009.

Pirhonen, M. 2010. Learning Soft Skills in Project

Management Course: Students´ Perceptions. In

Aramo-Immonen, H., Naaranoja, M. and Toikka, T.

(eds.) Proceedings of Project Knowledge Sharing

Arena, Scientific Track Project Days 2010, 31-41.

Roberts, E., 2000. Computing education and the infor-

mation technology workforce. SIGCSE Bulletin (32)2,

pp. 83-90.

Smith, B., Dodds, R., 1997. Developing Managers

Through Project-based Learning. Aldershot/Vermont:

Gover.

Tynjälä, P., Pirhonen, M., Vartiainen, T. and Helle, L.

2009. Educating IT project managers through project-

based learning: A working-life perspective. The

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, Vol. 24, Article 16, 270-299.

von Glasersfeld, E. 1984. An introduction to radical con-

structivism. In Watzlawick, P. (eds.) The Invented Re-

ality. How do We Know What We Believe We Know?

Contributions to Constructivism, Norton, New York,

NY, 17-40.

Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in Society. The development

of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, MA.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

328