Collaborative Annotation of Recorded Teaching Video Sessions

Florian Matthes and Klym Shumaiev

Lehrstuhl für Informatik 19 (sebis), Technische Universität München, Boltzmannstr. 3, Garching b. München, Germany

Keywords: Collaborative Annotation, Learning Video, Note-taking, Web Application.

Abstract: Driven by technology advances the availability of digital video recordings of live training sessions increases

at a fast pace. The goal of our research is to better understand the impact of these digital artifacts on the

individual (and possibly collaborative) note-taking process of learners. In this paper, we develop a

conceptual framework describing the augmentation of teaching sessions by computer-supported tools. We

use the framework to describe related work and to outline our research design that involves the development

of a minimum viable collaborative annotation tool and the study of the effects of variations in tool

functionality (like visibility of annotations, kinds of annotations, or form of annotations) on the learning

process. The scientific contribution of the conceptual framework and tool are to serve as a starting point for

empirical research by us and others who analyses the effect of variations in collaborative annotation tool

design.

1 MOTIVATION

AND INTRODUCTION

Today a number of computer-supported solutions

aim to improve student learning behavior and

performance in the classroom environment. The

main enablers for these changes are availability and

price reduction of broadband internet as well as

portable hardware, like, smartphones, laptops and

tablets (Alvarez, 2011). For example, using mobile

and web services, without interruption of the

teacher’s presentation, students have the possibility

to interact between each other simply texting on

Facebook or Twitter (M.D. Roblyera, 2010)

(Gabriela Grosseck, 2008), to give a live feedback to

the teacher (Veronica Rivera-Pelayo, 2013) and to

collaborate on the presented material (Kam, 2005).

Another important change is that today teaching

sessions are often recorded, that allows students to

re-view the presented material as many times as they

need. According to a survey conducted at the

beginning of 2013 at the Technical University of

Munich, 86% of the students considered the

possibility to watch lecture video recordings as

important or very important (Technische Universität

München, 2013). 1353 students took part in this

survey. About two-thirds of the participants claimed

that lecture recordings are used by them for follow-

up of the courses and for exam preparations. Only

2% of the students stated that audio recordings were

sufficient.

Another technology-enabled change in the

educational system is the concept of Massive Online

Open Courses (MOOCs). Students interested in a

particular subject have the ability to acquire freely

available qualitative educational content (Lane,

2013). MOOCs also build on the idea of teaching

sessions but address a much wider audience outside

of the classroom and also make heavy use of video

recordings.

As a result, the amount of educational digital

content and tools for handling this content grows

rapidly. In institutions where teaching session

attendance is not mandatory, new educational

solutions and services create a free-market

environment enabling students to vote with their feet

to attend lectures live, to watch teaching sessions

online, or to skip lectures entirely (Scott Cardall,

2008). This is an example of a significant change of

behavior introduced through digital media.

It remains unclear, how learners post-process

educational content and what kind of services they

use. Our research goal is to understand how learners

annotate educational videos, to develop a minimum

viable tool to assist students in this process and to

study the effects of the tool on the behavior of

instructors and learners. In the future, we plan to

study effects of changes of the tool design (visibility

576

Matthes F. and Shumaiev K..

Collaborative Annotation of Recorded Teaching Video Sessions.

DOI: 10.5220/0004964205760581

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 576-581

ISBN: 978-989-758-020-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

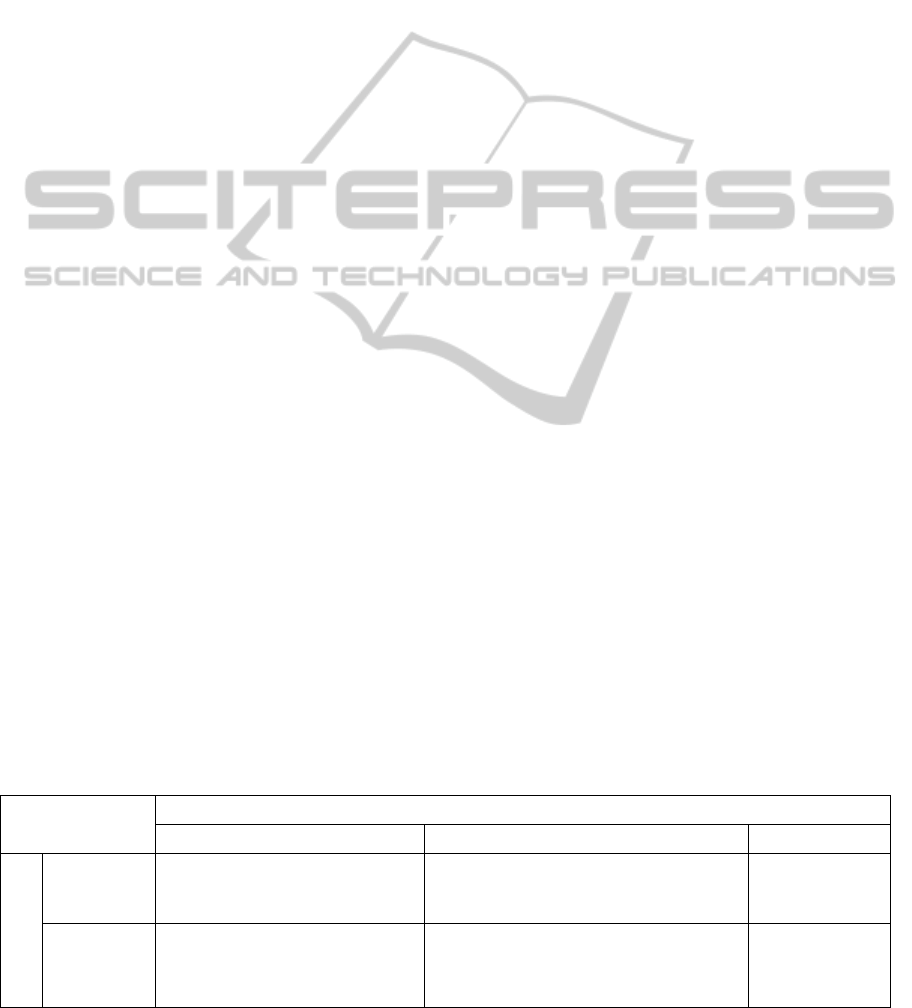

Table 1: Activities and content involved in a recorded live teaching session without additional computer-based tool support.

Phases

Preparation Live teaching session Post-processing

Actors

Instructor Plan timing of teaching

session.

Prepare teaching

material.

[Provide hand-out.]

Present teaching material.

Interact with students.

Record video.

Publish recorded video.

Learner [Process hand-out.]

[Take notes.]

Follow presentation.

[Interact with instructor.]

[Interact with other learners.]

[Take or review notes.]

[Watch recorded video]

[Review notes.]

[Share notes with other learners.]

of annotations, kinds of annotations, form of

annotations, etc.) as well. In this position paper, we

present the concepts underlying the tool, our

research questions and existing work regarding the

augmentation of teaching sessions in a unifying

conceptual framework. The goal of this position

paper is to get early feedback from the academic

community in computer-supported education.

2 A CONCEPTUAL

FRAMEWORK FOR

DESCRIBING AUGMENTED

TEACHING SESSIONS

This section introduces a conceptual framework to

explain the augmentation of teaching sessions by

video recording and annotation processes. We use

this framework to describe related work and to

explain our tool. In addition we clarify our

terminology and link our concepts to existing

research.

We use the general term teaching session to

describe a lecture, an exercise session, a seminar or

any kind of meeting where an instructor presents

teaching material (educational content) to one or

many learners. We call any teaching material made

available by a teacher to a student a hand-out and

any content created by a student a note. An

annotation is a note added to a special part of

teaching material.

In Table 1, we schematically illustrate a

conceptual framework where rows introduce actors

participating in the process. Up to now we only

distinguish between two kinds of actors: instructor

and learner.

Columns represent phases which help to

describe the synchronous and asynchronous

interactions (information flows) between actors over

time. The preparation phase includes the set of

activities aimed to prepare for the live teaching

session. The live teaching session phase subsumes

the synchronous interactions between actors and

their interactions with possible content. The post-

processing phase covers all actions performed by

actors with content created in the first two phases.

Cells describe actors’ activities (verbs) and

content (nouns) involved in these activities. Optional

activities are enclosed in brackets [].

Table 1 describes the basic collaborative process

of a live teaching session recorded by a video

without any additional computer-based tool support.

3 AUGMENTED TEACHING

SESSIONS

3.1 Note-taking and Annotation

without Use of a Special Tool

Steimle et al. survey 408 learners, where 316 were

students in computer science and 92 were students in

a pedagogy course (Steimle, 2007). No additional

tool for note-taking had been offered to the learners.

Table 1 provides an overview of the present study.

The study showed that numerous key characteristics

of traditional note-taking with pen and paper are

comparable with those of electronic notes on a

laptop. No differences between the two groups were

found in the types of notes taken, both in the post-

processing phase as well as in collaborative

activities. It should be noted that in the context of

this study collaborative activity means sharing hand

written notes between students after a live teaching

session, for example, to compare each other’s notes,

or copying notes in case one learner didn’t attended

the teaching session.

The study identified different types of content

CollaborativeAnnotationofRecordedTeachingVideoSessions

577

and their combination that were used to take notes

on:

printed slides;

empty sheets of paper;

empty sheets of paper and printed slides;

laptop;

laptop and empty sheets of paper;

laptop and printed slides.

Different types of software, that allows to annotate

the electronic course slides (e.g. Adobe Acrobat), or

word processors and text editors, were used by

learners for note-taking on the laptop. The data

shows that the ratio between students annotating

hand-outs and students taking notes on blank sheets

did not change if compared to the students

annotating slides on a laptop and students taking

notes using text editors.

The authors state that the discipline proved to be

an influential factor since laptop use differed largely

between the disciplines. In the pedagogy course,

laptop use was almost not existent and learners took

notes exclusively on paper.

Moreover, different advantages of taking notes

on paper and using laptop were identified. Learners

taking notes on a laptop valued that:

notes can be more easily modified;

it offers a cleaner appearance;

learners do not have to print the slides;

a laptop allows them to keep the information in

one place.

Those who take notes on paper stated that it is easier

and faster than note-taking on a laptop. All

participants valued the flexibility of free-form notes

on paper.

Another interesting finding was related to the

post-processing phase. The results show that in

contrast to the follow-up activities after class,

students become more active when preparing for the

exam.

In conclusion, the following implications for

future annotation systems were derived:

support of handwritten input;

support of both annotations and notes on blank

pages;

provide enough free space for annotations;

support of several languages;

support of collaboration;

adaptability to the specific context.

This study suggests that note-taking behaviour

largely depends on a complex multitude of context

aspects. Annotation systems must account for this

dependency. Therefore, they must be adaptable in

their central functionality (like support for

annotations vs. notes on blank pages, input modality,

types of the notes and collaborative features) to fit

the different user needs and teaching styles in

specific context situations.

3.2 Annotation using Special Tool

Kam et al. developed a system for cooperative

annotation in lectures (Kam, 2005). Table 2 shows

what types of activities and content were involved in

the overall process. To save place we do not include

activities that were mentioned in Table 1, but it is

considered that they were conducted as they are part

of a usual educational process. Unfortunately, there

is no information available on how the produced

notes were used during the post-processing phase,

nor about the availability of the teaching session

video recordings.

The following activities have been identified

when students create collaborative annotations of

hand-outs:

summarizing the entire slide;

posing questions to provocative bullet points;

answering questions framed as bullet points;

appending items to a list of sub-bullet points;

annotating specific bullet points;

listing additional ideas, examples, and issues in

response to bullet points;

raising objections and alternative reasoning;

criticising the choice of images or examples in

slides;

Table 2: Activities and contents involved in a teaching session where an annotation tool has been offered to the learners.

Phases

Preparation Live teaching session Post-processing

Actors

Instructor Upload hand-outs to the system.

[Give instruction how to use the

provided tool.]

[Follow the real-time feedback.] -

Learner

(with tool

access)

- Annotate the hand-out.

Read and comment annotation.

[Provide feedback about the speed of the

teaching session.]

-

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

578

explaining the meaning of abbreviations; and

complaining that the proposed design steps in a

slide do not apply to the problem at hand, and

correcting these.

Learners also added new details to bullet points,

especially when they contained examples.

In the collaboration environment learners appear

to find it important to explicitly distinguish between

teaching material and annotations.

The following implications were derived:

The need to enable learners to bring the instructor

into the loop whenever necessary, such as when

learning difficulties surface that students cannot

resolve on their own.

Certain aspects of collaborative note-taking and

dialogue are related to social expectations and

norms. For instance, some collaboration groups

seemingly broke down when the one or two

members with tool access were not contributing to

the shared note-taking and discussion.

It is noticeable that researchers at that time were

struggling with the lack of efficient portable

hardware and insufficient cross-platform technology

for collaboration. However, the research showed

how collaboration on the note-taking process

changed the style of notes. Comparison of individual

notes and collaborative group notes confirmed that

the last one had far more comments, questions and

answers. The study has shown that student

interactions with presentation slides during teaching

session alone are much broader and richer than

simply capturing the spoken part of the lecture.

Augmented note-taking or in other words annotation

of instructors’ content is likely to support

cooperative learning greatly. Teaching material

presented in the collaborative environment such as

the instructors’ slides can provide learning objects

that invite learners to interact with them.

3.3 Web-based Tagging of Recorded

Teaching Session

Shen et al. describe a web-based system that allows

learners to collaboratively annotate a video stream

using predefined tags (Shen, 2011). The video

stream was broadcasted from the live teaching

session. The authors argue that the cognitive gaps

between different learners’ note-taking are apparent,

even though they are annotating the same teaching

session slide. The collaborative learning may

increase the redundancy rather than create learning

efficiency. Due to this hypothesis and proposals of

other researches (Bateman, 2007), the authors

assume that collaborative tagging is one of the

solutions that can improve collaborative annotation.

In Table 3 we describe which actions and contents

are involved in the overall process of the system.

The main feature of the system developed by

Shen et al. (2011) is a wave-shape timeline chart

where learners are able to see which predefined tags

(good, question, disagree, etc.) that were used during

a teaching session. That allows identifying hot spots

of the recorded video and does not require a text

input.

3.4 Collaborative Annotation Tool for

Recorded Teaching Session Video

In this section we introduce our tool that is based on

the idea of having a specific collaboration

environment for the different phases of the teaching

process: the live teaching session and the post-

processing phases (see Table 4 on the next page).

The activities and contents of Table 4 extend the

activities and contents of Table 1.

The processes of note taking during the live

teaching session may differ from the one in the post

processing phase since in first case learners should

follow the instructors’ presentation and don’t have

much time to write long notes, while in the second

case the recorded video can be stopped or replayed.

As we observe from the previous studies, it was not

convenient for learners to start using a tool for

collaborative note-taking during the live teaching

session until they got an instruction how to use it

(Kam, 2005). At the same time, in the study of

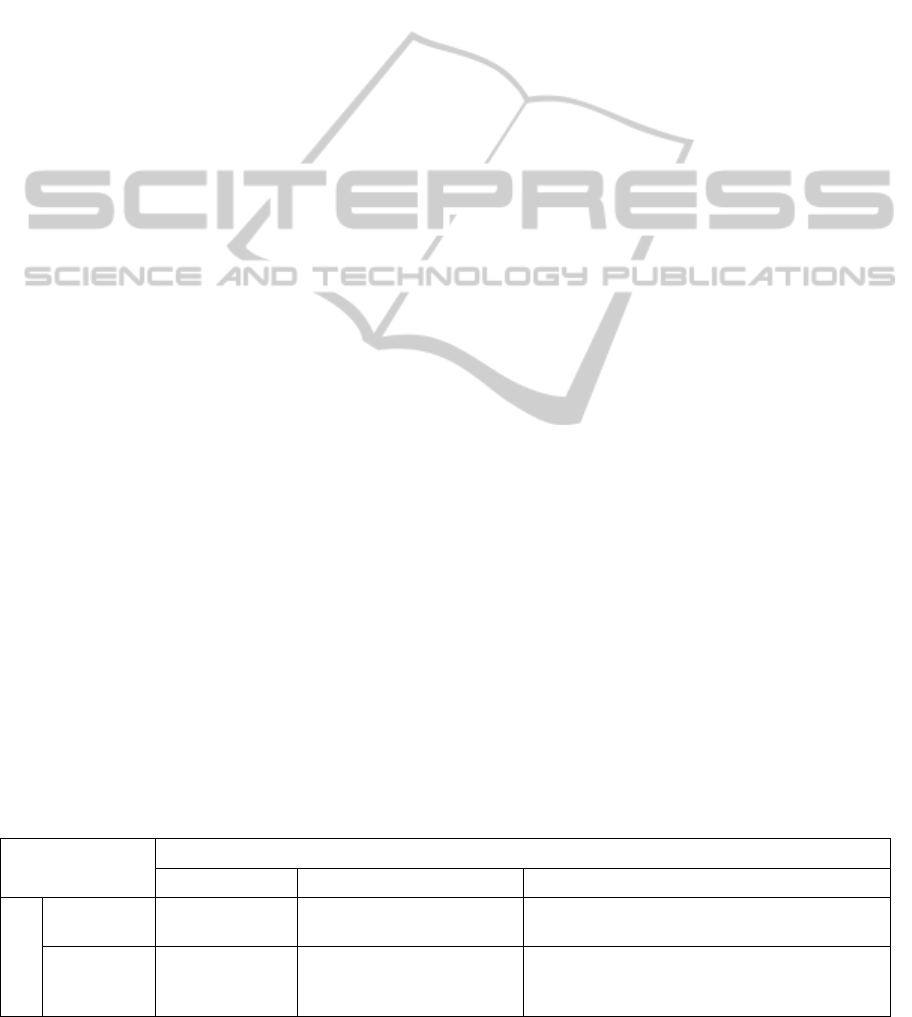

Table 3: Activities and contents involved in a teaching session where a special tool for tagging and video viewing has been

offered to the learners.

Phases

Preparation Live teaching session Post-processing

Actors

Instructor - Broadcast video stream.

Record the video.

-

Learner Access system. Add tag to streaming video.

View tag intensity chart.

View recorded video.

Navigate through recorded video using tag

intensity chart.

CollaborativeAnnotationofRecordedTeachingVideoSessions

579

Table 4: Collaborative annotation for recorded teaching session video (see text).

Phases

Preparation Live teaching session Post-processing

Actors

Instructor - View annotation. View and create annotation.

Learner - Create and view annotation. Create and view annotation.

Table 5: Possible synchronous and assynchronous collaboration via video annotations. Arrows show possible synchronous

and assynchronous collaboration.

Phases

Preparation Live teaching session Post-processing

Actors

Instructor

Learner

Steimle et al. (2007) learners use on their own

standard software to annotate presentation slides or

simple text editors to take notes. Therefore, the user

interface for taking notes during a teaching session

should have a similar user interface to commonly

used software; in this case the tool will be easy to

adopt.

To enable the transition of annotations during

live teaching session to the post-processing phase we

will synchronize the video stream with notes taken

when the particular frame of the video was captured.

The most challenging part of the annotation

system will be the collaborative aspect. As it will

influence the user interface and have to be

implemented in a way clearly understandable for

users. Moreover, various collaboration scenarios

have to be revised. In Table 5 we show possible

collaboration activities related to the annotations

during the overall process. Using this table we can

observe what actors have to be present in the system

and what rights for collaboration they will have

during each phase.

As shown in Table 4 and Table 5 our minimal

viable tool will only contain a small set of

functionalities and collaboration scenarios. That is

done on purpose, since at the beginning of our study

we would like to evaluate only the basic

functionality and avoid creating possibly unused and

distracting functionality.

4 FUTHER RELATED WORK

There are a few researchers as well as commercial

projects that study (video) annotation and retrieval

processes during meetings in enterprise

environments. Their results are relevant because a

meeting with a presenter and an audience is similar

to a teaching session.

Nathan et al. focus on the ability of people to

retrieve information from a meeting, and provide a

special tool for collaborative annotation of live

meetings (Nathan, 2012). As repositories of such

recorded video meetings grow, the value and utility

of these stores will depend on providing tools that

help users to quickly browse, find and retrieve

elements of interest. Given the long time (and high

costs) required to view a recorded meeting in its

entirety, there is a need for tools that assist in

efficient information retrieval. This is particularly

true for people who missed a meeting, who

frequently choose to learn about the proceedings

from a colleague (Banerjee, 2005), rather than invest

the time viewing its recording.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper we presented the design of a minimum

viable web-based tool for collaborative video

annotations of teaching sessions based on findings of

existing research and development regarding

augmented teaching sessions. For this purpose we

developed and used a unifying conceptual

framework based on three phases, two types of

actors, and activities using four types of artifacts

(teaching material, hand-outs, notes and

annotations).

The scientific contribution of the tool and the

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

580

framework are to serve as a starting point for

empirical research by us and others that studies the

impact of variations in tool design (like the visibility

of annotations in different phases, kinds of

annotations and notes, form of annotations, and

design of the user interface) on the behavior of the

learners and also of the teacher.

We are currently implementing the tool using

standard web technologies and are designing the

experiments (research questions, hypotheses and

measurement techniques) to be carried out in an

iterative and incremental way starting with the

minimum viable tool in the near future.

In our future work, we want to allow learners to

create both, private and shared notes. This allows the

learner to search only private notes.

Navigation should allow learners to jump from a

particular annotation to the exact time of the video

when it has been created.

A further extension would be to support two

different ways of note representations in the system:

One interface for “static” notes (relating to the

whole teaching session) and another for annotations

displayed dynamically (synchronized with the

video).

REFERENCES

Alvarez, C. a. B. C. a. N. M., 2011. Comparative Study of

Netbooks and Tablet PCs for Fostering Face-to-face

Collaborative Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav., March,

pp. 834--844.

Banerjee, S. C. R. a. A. I. R., 2005. The necessity of a

meeting recording and playback system, and the

benefit of topic–level annotations to meeting

browsing.. Human-Computer Interaction-INTERACT

2005, pp. 643-656.

Bateman, S. C. B. a. G. M., 2007. Applying collaborative

tagging to e-learning. s.l., ACM.

Gabriela Grosseck, C. H., 2008. Can we Use Twiter for

educational activities?. Bucharest, s.n.

Kam, M. W. J. I. A. T. E. C. J. G. D. T. O. C. J., 2005.

Livenotes: A System for Cooperative and Augmented

Note-Taking in Lectures. s.l., s.n., pp. 531-540 .

Lane, A., 2013. The potential of MOOCs to widen access

to, and success in, higher education. Paris, The Open

and Flexible Higher Education Conference 2013, 23-

25 October 2013, EADTU, p. 189–203.

M. D. Roblyera, M. M. M. W. J. H. J. V., 2010. Findings

on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of

college faculty and student uses and perceptions of

social networking sites. The Internet and Higher

Education, June, p. 134–140.

Nathan, M. a. T. M. a. L. J. a. P. S. a. W. S. a. B. J. a. T.

L., 2012. In Case You Missed It: Benefits of

Attendee-shared Annotations for Non-attendees of

Remote Meetings. Seattle, Washington, USA, ACM.

Scott Cardall, D. E. K. M. U., 2008. Live Lecture Versus

Video-Recorded Lecture: Are Students Voting With

Their Feet?. Academic Medicine, 12 December, pp.

1174-1178.

Shen, Y. T. a. J. T.-S. a. H. Y.-C., 2011. A "Live"

Interactive Tagging Interface for Collaborative

Learning. Hong Kong, China, Springer-Verlag.

Steimle, J. I. G. a. M. M., 2007. Notetaking in University

Courses and its Implications for eLearning Systems.

DeLFI, Volume 5, pp. 45-56.

Technische Universität München, 2013. Ergebnisse der

Studierenden-Umfrage. (Online) Available at:

http://www.it.tum.de/en/projects/vorlesungsaufzeichnu

ng/umfrage-studierende/ (Accessed 18 December

2013).

Veronica Rivera-Pelayo, J. M. V. Z. S. B., 2013. Live

Interest Meter: Learning from Quantified Feedback in

Mass Lectures. Leuven, Belgium, ACM.

CollaborativeAnnotationofRecordedTeachingVideoSessions

581