Towards a General Framework for Business Tests

Marijke Swennen

1

, Benoît Depaire

1,2

, Koen Vanhoof

1

and Mieke Jans

1

1

Business informatics research group, Hasselt University, Agoralaan Building D, 3590 Diepenbeek, Belgium

2

Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), Egmontstraat 5, 1000 Brussels, Belgium

Keywords: Business Test, Problem Definition, Performance, Compliance, Risk, Design Science.

Abstract: Testing and controlling business processes, activities, data and results is becoming increasingly important

for companies. Based on the literature, business tests can be divided into three domains, i.e. performance,

risk and compliance and separate domain-specific frameworks have been developed. These different

domains and frameworks hint at some aspects that need to be taken into account when managing business

tests in a company. In this paper we identify the most important concepts concerning business tests and their

management and we provide a first conceptual business test model. We do this based on an archival

research study in which we analyse business tests performed by an international consultancy company.

1 INTRODUCTION

In classical management theory, Fayol (1949)

identified five ‘elements’ of management, among

which Controlling is one. While the validity of

Fayol’s work has been subject of academic debate

(Fells, 2000), there is little arguing that companies

are increasingly confronted with incentives and

obligations to test and control their business (Wade

and Recardo, 2001; Shamsaei et al., 2010). These

business tests entail any kind of test on business

objects such as a process, an activity, an employee

or a product.

The need for business testing stems from different

origins, such as legislation compliance requirements,

Service Level Agreements (SLAs) or performance

management (Wade and Recardo, 2001). We argue

that due to the diverse nature of business test

incentives, management of business tests is often

without a holistic overview, fragmented and as a

consequence possibly inefficient.

The objective of this paper is threefold: we

provide a rationale for a consolidated view of

business tests, a working definition of business tests

and identify various dimensions of business tests.

This research is a first step towards a general

framework to identify, model and manage business

tests.

Section 2 and 3 will respectively describe the

applied research methodology and the data, while

section 4 introduces the rationale for a consolidated

business test framework. Next, section 5 will discuss

the definition and several dimensions of business

tests. Conclusions and future work will be discussed

in section 6.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research described in this paper is part of a

bigger research project with the objective to develop

models, methods and a language for a holistic

business test framework. The nature of these overall

research objectives demand for the scientific

paradigm of Design Science research (Hevner et al.,

2004, Peffers et al., 2007). This paper presents the

first steps of this paradigm, i.e. the problem

identification, the research motivation and a first

iteration to define a business test artefact.

All results were derived through literature review

and archival research. Firstly, a literature review of

existing work on business tests was performed

according to the steps by Fink (2005). Based on the

gained insights, the business test artefact was

developed.

Next, archival research on a set of 156 business

tests, provided by 4 different business units of an

international consultancy company, was performed

to evaluate to what extent the different elements of a

business test artefact can and have been applied.

The archival research findings were further

enriched by qualitative interviews with various

478

Swennen M., Depaire B., Vanhoof K. and Jans M..

Towards a General Framework for Business Tests.

DOI: 10.5220/0004969204780483

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 478-483

ISBN: 978-989-758-029-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

employees actively working with business tests at

different levels in the business test cycle, such as

developing, implementing, performing, evaluating

and improving business tests. The seven stages of

conducting interviews, stated by Kvale and

Brinkmann (2008), were applied.

3 DATA

For our archival research study, we selected an

international consultancy company as our case study

as it consists of different business units performing

business tests for different reasons. In total 4 units

were selected, i.e. Audit & Risk, Forensics, Tax and

Consulting, from which a convenience sample of

156 was drawn. Please note the exploratory nature of

this research which justifies the use of a convenience

sample.

The tests performed in the first business unit,

Audit & Risk, define the risk level of a client

company. The second business unit performs all

tests related to Forensics, which concerns the risk

and compliance level of a company. Tax is a

business unit in which all kinds of tests concerning

VAT and applied VAT rates are performed. These

are defined as compliance tests that result from rules

or laws the client companies need to obey to.

Finally, the Consulting business unit performs tests

to provide advice to client companies about different

elements such as pricing or customer orientation.

These tests can be categorized as performance tests.

The number of tests performed by each business

unit, is given in table 1.

Table 1: Overview of all tests per business unit in the case

study.

Business Unit

Number of tests

Audit & Risk 31

Forensics 75

Tax 36

Consulting 14

Total 156

4 AN INTEGRATED BUSINESS

TEST FRAMEWORK

Research on business tests has been done in three

business domains, i.e. performance management,

compliance management and risk management.

Within each domain, several separate models and

frameworks have been developed. For a

comprehensive overview of trends and different

frameworks in each domain, the reader is

respectively referred to Bourne (2001) or Bititci et

al. (2011), Mahmoud (2010) and O’Donnell (2005).

The fact that each research domain presents its

own frameworks is also reflected in the business

reality where an integrated approach towards

business tests is often lacking. Although each

business unit of the company in our archival

research study identifies its tests as exclusively

related to either performance, compliance or risk,

some tests can actually be assigned to multiple

domains. However, two lines of arguments can be

developed in favour of a more integrated approach.

Firstly, from a management perspective,

isolating business test efforts from each other, could

lead to inefficiencies. Shamsaei et al. (2010)

mention that different business rules might be

correlated and actions to improve the results for one

rule might have side effects on other rules. Being

unaware of such correlations leads to

suboptimisation. Also, measuring and evaluating

highly similar and even duplicate tests for different

perspectives, will create an administrative burden.

Furthermore, Bardoliwalla et al. (2009) state that

risk management is often hampered by

organizational silos, causing a lack of consistent

taxonomies, measurement, and reporting. This

results in obscured visibility, preventing managers to

obtain a true picture of the overall enterprise. It is

expected that their observation gains even more

importance when expanding to the full range of

business tests.

A second line of arguments in favour of an

integrated business test framework originates from

the information systems perspective. Business tests

deal with measuring and gathering the correct data

and providing it timely to the right manager,

preferably in an automated way. Consequently,

business tests should be an integrated part of the

information architecture and have a direct impact on

the data and system requirements. Strangely, while

several frameworks, models and languages exist to

provide an overview of the data architecture and the

business process architecture, no such framework

exists for business tests. Consequently, if a manager

asks the IT department for the implementation of a

new business test, the development team lacks a

complete overview of the existing business tests.

The idea of an integrated approach is not entirely

new and recently a few researchers have hinted at a

similar idea. A first attempt is the GRC concept,

TowardsaGeneralFrameworkforBusinessTests

479

which combines governance with risk and

compliance management and is an emerging topic in

the business domain (Racz et al., 2010).

Bardoliwalla et al. (2009) further combine the GRC

concept with performance management, merging the

main three sources of business tests. While the work

of Bardoliwalla et al. (2009) unifies the three

concepts of performance, risk and compliance into a

coherent strategic management process framework,

they do not provide an integrated framework how to

design, implement and document business tests.

5 THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

FOR A BUSINESS TEST

A test can be defined as the evaluation of a

measurement against a predefined target, where

the evaluation process results in a conclusion

about the measured object.

For example, to test whether we should stop at

the current gas station entails measuring the current

fuel level and evaluating it against the fuel level

target required to drive to the next gas station. Based

on this evaluation we can conclude if we make it to

the next station.

A Business Test is then a test that relates to any

kind of business object, such as e.g. a product or

process, and is typically related to some kind of

performance, risk or compliance purpose (or a

combination of them as we discussed in section 4).

Note that we define a business test at the lowest

(most detailed) measurement level.

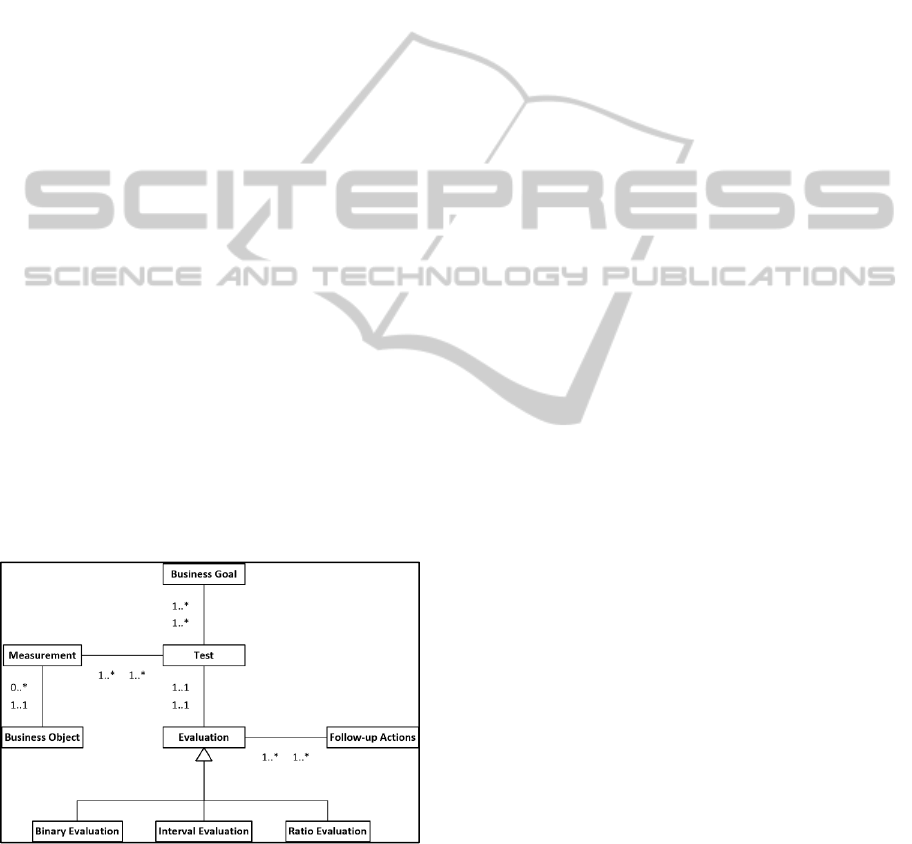

Figure 1: The conceptual model of a business test.

With this general definition of a business test, we

proceeded to analyse the literature to develop a

conceptual model for a business test, which is

illustrated in Figure 1. We identified concepts from

the performance, compliance and risk literature that

were relevant to a general business test concept.

Next, archival research evaluated if the different

elements of a business test made sense in practice.

Simultaneously, we explored to what extent our set

of business tests were complete in the sense of our

conceptual model.

Business Object

5.1

From our conceptual model in Figure 1 we can argue

that a business test should always be indirectly

linked to a business object via a measurement. A

measurement is an observation of a business object,

i.e. the number of steps in a process or the average

weight of a specific product, but is never a

comparison between two things, which is the

evaluation. A measurement is always related to only

one object but more than one measurement can be

necessary to perform a test. As a result, a single

business test can be concerned with several business

objects which means that several business tests may

be required to evaluate a specific aspect of the

company. The evaluation is the formula or metric

and the target with which the measured value will be

compared to define a conclusion.

For almost all business tests performed at the

international consultancy company a link with a

business object can be found. The Forensics and

Consulting business units, for example, both define

eleven business tests to check the quality of master

data of a client company. This implies that different

tests are performed to evaluate the quality of master

data. Furthermore, in the Audit & Risk business unit,

all tests perform a check on data from the purchasing

process in client companies. For each test a certain

measure of this process is stored. To conclude we

can state that for almost all tests at the different

business units of our case study company a link to a

business object is defined.

5.2 Business Goal

One of the frameworks in the performance

measurement domain, defined by Neely et al.

(2000), states that performance measures should

always be linked to the company’s strategic

objectives. Following this thought, we can argue that

business tests should be connected to one or more

business objectives or goals and that these goals

should be properly documented.

Most of the tests in the different lists of our

archival research do not include any objective or

goal. Only the list of tests from the Forensics

business unit includes for every set of tests an

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

480

objective. However, after analysis, these objectives

are found to be explanations of how the tests will be

performed and cannot be regarded as business goals.

For example, for the quality of master data tests, the

given objective is to identify missing critical master

data for customers and suppliers. This only gives an

overview of the different checks that will be

performed. From this we can conclude that the

objectives of the business tests in our sample are not

documented. Some additional questions at the

consultancy company tell us that the overall goal of

the different business units is to make sure the client

company is satisfied with the delivered service.

Furthermore, the interviews tell us that at Audit &

Risk the objectives are mostly to look for fraud and

irregularities in client data. This is something they

only started documenting very recently and is not

standardized or implemented yet.

5.3 Evaluation Scales

We defined a test as the evaluation of a

measurement against a predefined target, where the

evaluation process results in a conclusion about the

measured object. The risk management framework

developed by Kaplan and Mikes (2012) presents a

categorization of risks that allows to tell which

actions to take for and how to evaluate each risk

category. The first category are preventable risks,

which arise from within the organization. They are

controllable, should be eliminated or avoided and

are best managed through active prevention. This

implies a binary evaluation, the risk should be

corrected immediately if it occurs.

Category two are strategy risks that are quite

different from preventable risks because they can be

assumed to be not inherently undesirable.

Sometimes it is required to take on significant risks,

and managing those risks can be an important factor

in obtaining potential benefits. A risk management

system is required to reduce the probability that the

assumed risks occur and to improve the ability to

contain or monitor the ratio between performance

and risk. Here a ratio evaluation is implied which

requires measurements of different objects.

The third category are risks which arise from

events outside the company and are therefore

beyond its influence or control. Causes may be

natural or political disasters and major

macroeconomic shifts. With an interval evaluation

management should focus on measuring and

mitigating the impact of these risks because they

cannot be prevented from occurring.

At the Tax business unit all tests are evaluated

with ‘ok’ or ‘not ok’. This implies no toleration or

trade-off for the results of these tests. In the list of

tests from Forensics, some guidance steps for the

client company are provided in case risky or

unreliable results occur. All test results are evaluated

by checking their importance or impact, which

implies a ratio evaluation. From this we can

conclude that for some business units of our archival

research company a notion of ways to evaluate the

results is present. However, this is only true for two

of the four business units in the study.

5.4 Follow-up Actions

Based on the different categories of risk presented in

the risk management framework of Kaplan and

Mikes (2012), we can argue that all categories have

one thing in common. For a proper management of

risks not only measuring their impact is of

importance, also the identification of which actions

to take in mitigating or managing these risks should

be included. This refers to the conclusion in our

general definition of a business test. We can transfer

this idea to the business concept by stating that for

every business test the possible follow-up actions

and triggers to activate these actions should be

defined. Based on the three types of risks, we see

that different types of risks can have a different

influence on how each test should be evaluated and

which follow-up action should be performed. We

can add the notion that a follow-up action of a

business test can be another business tests. This is

also discussed in section 5.6.

In the Forensics and Tax business units we find

that for only a small amount of tests follow-up

actions are included. At Tax, most of the defined

follow-up actions are manual checks or the delivery

of a list of transactions with standout results to the

client company. In five of the tests performed by the

Tax business unit a business test is followed by

another business test if a certain result occurs.

However, there is no documentation about which

actions to take to prevent, manage or mitigate certain

risk events.

5.5 Weights

In the compliance management domain we find the

approach developed by Shamsaei et al. (2010) which

enables organizations to measure the current

compliance level of their processes and track down

and analyse compliance problems. Measuring the

importance of organizational rules allows to

distinguish the most important problems that need to

TowardsaGeneralFrameworkforBusinessTests

481

be assigned first from the less important problems.

By expanding these conclusions to the business test

concept, we can argue that giving weights to

business tests can provide an insight in which tests

and which resulting outcomes need to be covered

first. Moreover, an overall measure of compliance

can be found by providing more important tests with

a higher weight.

The notion of different weights given to business

tests could not be found in the lists of business tests

we received from the different business units of the

consulting company. The tests are presented as

being all at the same level, implying that they all

have the same weight or importance. Some

additional questions at the company tell us that these

weights and their documentation appear to be

interesting but are not yet developed or

implemented.

5.6 Intertest Relationships

Besides the notion of weights, Shamsaei et al.

(2010) also argue that more than one rule possibly

applies to a single process, and hence a change to

enhance the compliance level of one rule may have

side effects on the compliance level of other rules.

Transferred to the concept of business tests, we can

argue that the result or outcome of a business test

can be influenced by the implementation or the

result of another business test. This adds to the

findings that business tests can be follow-up actions

of other business tests. In the conceptual model in

Figure 1, this interest relationship is indirectly given

by the many-to-many relationship between objects

and tests. The business objects represent the link

between different business tests.

We already mentioned that some business tests

from the international consulting company are

followed by other business tests, but there is no

information about the influence of different business

tests and their results on each other.

6 CONCLUSIONS

From the literature review we can infer that the

different business test domains, i.e. performance,

compliance and risk, are only recently brought in

connection to each other. Most existing frameworks

concern only one of these domains. However, in this

research we found that some business tests are not

exclusively assignable to just one of these domains.

Furthermore, we noticed that in many cases,

business testing and the management of these tests

fall victim to organizational silos, lacking consistent

taxonomies, measurement, and reporting, which

obscures visibility.

In this first step of our overarching research

project to develop a holistic business test framework

we define a business test as an evaluation of a

measurement against a predefined target, where the

evaluation process results in a conclusion about the

measured object. Furthermore we state that business

tests are grouped around a business object and

connected to a higher business objective. The

evaluation scale, weight and follow-up actions,

which can be other business tests, should be defined

and intertest relationships may be present.

The need for a proper management of business

tests becomes clearer when adding the findings from

the archival research study. In this study we found

that the objectives of the business tests are not

documented properly and that no weights are

provided to the business tests as suggested by the

literature. Besides that, only a small amount of the

tests in the study include a notion of follow-up

actions and ways to evaluate the results of the tests.

However, most of the tests can be divided in

different groups around objects in the company.

Finally, we can conclude that valuable information

is trapped in the different departments of the

organization and is not aggregated with information

from other departments. Especially for the steps

before actually performing the tests, the data

collection and data cleaning, a lot of redundancy is

present.

In general, these results empirically validate the

need for an integrated framework for defining and

implementing business tests, as only some of the

business test elements are present.

After performing this first step in the Design

Science Research Methodology Cycle, the next steps

can be executed. In cooperation with some experts

working with the business tests in our archival

research the tests can be transferred into our

conceptual model. Appropriate enhancements or

modifications can be implemented.

However some challenges and different

perspectives can provide an even better basis for this

first step. First of all, we can assume that different

companies can be in a different maturity level in

terms of the development and implementation of

business tests and the structure of business tests.

Also, the same research can be carried out on tests

performed at companies on their own data instead of

consultancy companies who perform tests at client

data.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

482

REFERENCES

Bardoliwalla, N., Buscemi, S., Broady, D., 2009. Driven

to Perform: Risk-Aware Performance Management

From Strategy Through Execution. Evolved

Technologist Press. New York, 1

st

edition.

Bititci, U, Garengo, P., Dorfler, V., Nudurupati, S., 2011.

Performance measurement: challenges for tomorrow.

In International Journal of Management Reviews 14

(3). p. 305–327.

Bourne, M., 2001. Handbook of Performance

Measurement. Gee Publishing Limited, London.

Fayol, H., 1949. General and Industrial Management. Sir

Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd. London.

Fells, M. J., 2000. Fayol stands the test of time. In Journal

of Management History, 6 (8), p. 345–360.

Fink, A., 2005. Conducting Research Literature Reviews.

From the Internet to Paper. Sage Publications. 2

nd

edition.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., Ram, S., 2004.

Design Science in Information Systems Research, In

MIS Quarterly, 28 (1), p. 75-105.

Kaplan, R. S., Mikes, A., 2012. Managing Risks: A New

Framework. In Harvard Business Review. 90 (6), p.

48-60.

Kvale, S., Brinkmann, S., 2008. InterViews: Learning the

Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE

Publications, Inc.

Mahmoud, A., 2010. A compliance management

framework for business process models. Ph.D. Thesis.

Germany, University of Potsdam.

Neely, A., Bourne, M. Kennerley, M., 2000. Performance

measurement system design: developing and testing a

process-based approach. In International Journal of

Operations & Production Management. 20 (10). p.

1119-1145.

O’Donnell, E., 2005. Enterprise risk management: A

system-thinking framework for the event identification

phase. In International Journal of Accounting

Information Systems. 6 (3). p. 177-195.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M., Chatterjee,

S., 2007. A Design Science Research Methodology for

Information Systems Research, Journal of

Management Information Systems. 24 (3). p. 45-77.

Racz, N., Weippl, E., & Seufert, A., 2010. A frame of

reference for research of integrated governance, risk

and compliance (GRC). In Communications and

Multimedia Security, p. 106–117.

Shamsaei, A., Pourshahid, A., Amyot, D., 2010. Business

Process Compliance Tracking Using Key Performance

Indicators. In 6th Int. Workshop on Business Process

Design (BPD 2010), BPM 2010 Workshops, LNBIP

66, Springer, p. 73-84.

Wade, D., Recardo, R., 2001. Corporate Performance

Management: How to build a better organization

through measurement-driven, strategic alignment.

Butterworth-Heinemann.

TowardsaGeneralFrameworkforBusinessTests

483