Data-driven Diachronic and Categorical Evaluation of Ontologies

Framework, Measure, and Metrics

Hlomani Hlomani and Deborah A. Stacey

School of Computer Science, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Road East, Guelph, Ontario, Canada

Keywords:

Ontology, Ontology Evaluation, Metric, Measure, Data-drive Ontology Evaluation, Ontology Evaluation

Framework.

Abstract:

Ontologies are a very important technology in the semantic web. They are an approximate representation and

formalization of a domain of discourse in a manner that is both machine and human interpretable. Ontol-

ogy evaluation therefore, concerns itself with measuring the degree to which the ontology approximates the

domain. In data-driven ontology evaluation, the correctness of an ontology is measured agains a corpus of

documents about the domain. This domain knowledge is dynamic and evolves over several dimensions such

as the temporal and categorical. Current research makes an assumption that is contrary to this notion and hence

does not account for the existence of bias in ontology evaluation. This work addresses this gap and proposes

two metrics as well as a theoretical framework. It also presents a statistical evaluation of the framework and

the associated metrics.

1 INTRODUCTION

The web we experience today is in fact a fusion of

two webs: the hypertext web that we are tradition-

ally accustomed to, also known as the web of docu-

ments, and the semantic web, also known as the web

of data. The latter is an extension of the former. The

semantic web allows for the definition of semantics

that enables the exchange and integration of data in

communications that takes place over the web and

within systems. These semantics are defined through

ontologies rendering them the centrepiece for knowl-

edge description. As a result of the important role

ontologies play in the semantic web, they have seen

increased research interest from both academic and

industrial domains. This has lead to the proliferation

of ontologies in existence. This proliferation can be

a double-edged sword, so to speak. Critical mass is

essential for the semantic web to take off, however,

in the context of reuse, deciding on which ontology

to use presents a big challenge. To that end a var-

ied number of approaches to ontology evaluation have

been proposed.

By definition an ontology is a shared conceptual-

ization of a domain of discourse. A conflicting factor

is that, while it is a shared conceptualization, it is also

created in a specific environmental setting, time, and

largely based on the modeller’s perception of the do-

main. Moreover, domain knowledge from which it is

based is non-static and changes over different dimen-

sions. These are notions that have been overlooked in

current research on data-driven ontology evaluation.

The ultimate goal is to answer the question: “How do

the domain knowledge dimensions affect the results

of data-driven ontology evaluation?” Consequently,

this paper presents a theoretical framework as well

as two metrics that account for bias along the dimen-

sions of domain knowledge. To prove and demon-

strate the merits of the proposed framework and met-

rics an experimental procedure that encompasses sta-

tistical evaluations is presented in the context of four

ontologies in the workflow domain. For the most part

the results of the statistical experimentation and eval-

uation are in support of the hypotheses of this paper.

There are, however, cases where the null hypotheses

have been accepted and the alternate rejected.

2 RELATED WORK:

DATA-DRIVEN EVALUATION

This evaluation technique typically involves compar-

ing the ontology against existing data about the do-

main the ontology models. This has been done from

different perspectives. For example, Patel et al. (Pa-

tel et al., 2003) considered it from the point of view

of determining if an ontology refers to a particular

56

Hlomani H. and A. Stacey D..

Data-driven Diachronic and Categorical Evaluation of Ontologies - Framework, Measure, and Metrics.

DOI: 10.5220/0005072700560066

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD-2014), pages 56-66

ISBN: 978-989-758-049-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

topic(s). Spyns et al. (Spyns, 2005) attempted to ana-

lyze how appropriate an ontology covers a topic of the

corpus through the measurement of the notions of pre-

cision and recall. Similarly, Brewster et al. (Brewster

et al., 2004) investigated how well a given ontology or

a set of ontologies fit the domain knowledge. This is

done by comparing ontology concepts and relations to

text from documents about a specific domain and fur-

ther refining the results by employing a probabilistic

method to find the best ontology for the corpus. On-

tology coverage of a domain was also investigated by

Ouyang (Ouyang et al., 2011) where coverage is con-

sidered from the point of view of both the coverage of

the concepts and the coverage of the relations.

The major limitation of current research within the

realm of data-driven ontology evaluation is that do-

main knowledge is implicitly considered to be con-

stant. This is inconsistent with literature’s assertions

about the nature of domain knowledge. For exam-

ple, Nonaka (Nonaka and Toyama, 2005) asserts that

domain knowledge is dynamic. Changes in ontolo-

gies have been partially attributed to changes in the

domain knowledge. In some circles, ontological rep-

resentation of the domain has been deemed to be bi-

ased towards their temporal, environmental, and spa-

tial setting (Brank et al., 2005; Brewster et al., 2004).

By extension, the postulation is that domain knowl-

edge would change over these dimensions as well.

Hence, it is the intent of this research to succinctly in-

corporate these salient dimensions of domain knowl-

edge in an ontology evaluation effort with the view

of proving their unexplored influence on evaluation

measures.

3 GENERAL LIMITATIONS OF

ONTOLOGY EVALUATION

This section discusses subjectivity as a common major

limitation to current research in ontology evaluation.

We demarcate this discussion into: (i) subjectivity in

the selection of the criteria for evaluation, (ii) sub-

jectivity in the thresholds for each criterion, and (iii)

influences of subjectivity on the results of ontology

evaluation.

3.1 Subjectivity in the Criteria for

Evaluation

Ontology evaluation can be regarded over several dif-

ferent decision criteria. These criteria can be seen as

the desiderata for the evaluation (Vrandecic, 2010;

Burton-Jones et al., 2005). The first level of diffi-

culty has been in deciding the relevant criteria for a

given evaluation task. It has largely been the sole re-

sponsibility of the evaluator to determine the elements

of quality to evaluate (Vrandecic, 2010). This brings

about the issue of subjectivity in deciding which cri-

teria makes the desiderata.

To address this issue, two main approaches have

been proposed in literature: (i) induction - empiri-

cal testing of ontologies to identify desirable proper-

ties of the ontologies in the context of an application,

and (ii) deduction - deriving the most suitable prop-

erties of the ontologies based on some form of theory

(e.g. based on software engineering ). The advantages

of these coincidentally seem to be the disadvantage

of the other. For example, inductive approaches are

guaranteed to be applicable for at least one context,

but their results cannot be generalized to other con-

texts. Deductive approaches on the other hand, can be

generalized to other contexts, but are not guaranteed

to be applicable for any specific context. In addition,

for deductive approaches, the first level of challenge

is in determining the correct theory to base the de-

duction on. This then spirals back to the problem of

subjectivity where the evaluator has to sift through a

plethora of theories in order to justify their selection.

3.2 Subjectivity in Thresholds

The issue of thresholds for ontology evaluation cri-

teria has been highlighted by Vrandecic (Vrandecic,

2010). He puts forward that the goal for ontology

evaluation should not be to perform well for all cri-

teria and also suggests that some criteria may even be

contradictory. This then defaults to the evaluator to

make a decision on the results of the evaluation over

the score of each criterion. This leads to subjectivity

in deciding the optimal thresholds for each criterion.

For example, if a number of ontologies were to be

evaluated for a specific application, it becomes the re-

sponsibility of the evaluator to answer questions like,

“Based on the evaluation criteria, when is Ontology

A better than Ontology B?.

3.3 Influences of Subjectivity on the

Measures/Metrics

The default setting of good science is to exclude sub-

jectivity from a scientific undertaking such as an ex-

periment (Nonaka and Toyama, 2005). This has been

typical of ontology evaluation. However, as has been

discussed in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, humans are the ob-

jects (typically as actors) of research in most ontology

evaluation experiments. The research itself therefore,

cannot be free of subjectivity. This expresses bias

Data-drivenDiachronicandCategoricalEvaluationofOntologies-Framework,Measure,andMetrics

57

from the point of view of the evaluator. There exists

another form of bias, the kind that is inherent in the

design of the ontologies. An ontology (a model of do-

main knowledge) represents the domain in the context

of the time, place, and cultural environment in which

it was created as well as the modellers perception of

the domain (Brank et al., 2005; Brewster et al., 2004).

The problem lies in the unexplored potential in-

fluence of this subjectivity in the evaluation results. If

we take a data-driven approach to ontology evaluation

for example, it would be interesting to see how the

evaluation results spread over each dimension of the

domain knowledge (i.e. temporal, categorical, etc.).

This is based on equating subjectivity/bias to the dif-

ferent dimensions of domain knowledge. To give a

concrete example, let us take the results of Brewster

et al. (Brewster et al., 2004). These are expressed as

a vector representation of the similarity score of each

ontology showing how closely each ontology repre-

sents the domain corpus. This offers a somewhat one

dimensional summarization of this score (coverage)

where one ontology will be picked ahead of the others

based on a high score. It, however, leaves unexplored

how this score changes over the years (temporal), for

example. This could reveal very important informa-

tion such as the relevance of the ontology, meaning

that the ontology might be aging and needs to be up-

dated as opposed to a rival ontology. The results of

Ouyang et al. (Ouyang et al., 2011) are a perfect ex-

emple of this need. They reveal that the results of

their coverage showed a correlation between the cor-

pus used and the resultant coverage. This revelation is

consistent with the notion of dynamic domain knowl-

edge. In fact, a changing domain knowledge has been

attributed to the reasons for changes to the ontologies

themselves (Nonaka and Toyama, 2005). This offers

an avenue to explore and account for bias as well as

its influence on the evaluation results. This forms the

main research interest of this paper.

Thus far, to the best of our knowledge, no research

in ontology evaluation has been undertaken to account

for subjectivity. This has not been especially done to

measure subjectivity in the context of a scale as op-

posed to binary (yes- it is subjective, or no - it is not

subjective). Hence, this provides a means to account

for the influences of bias (subjectivity) on the individ-

ual metrics of evaluation that are being measured.

4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

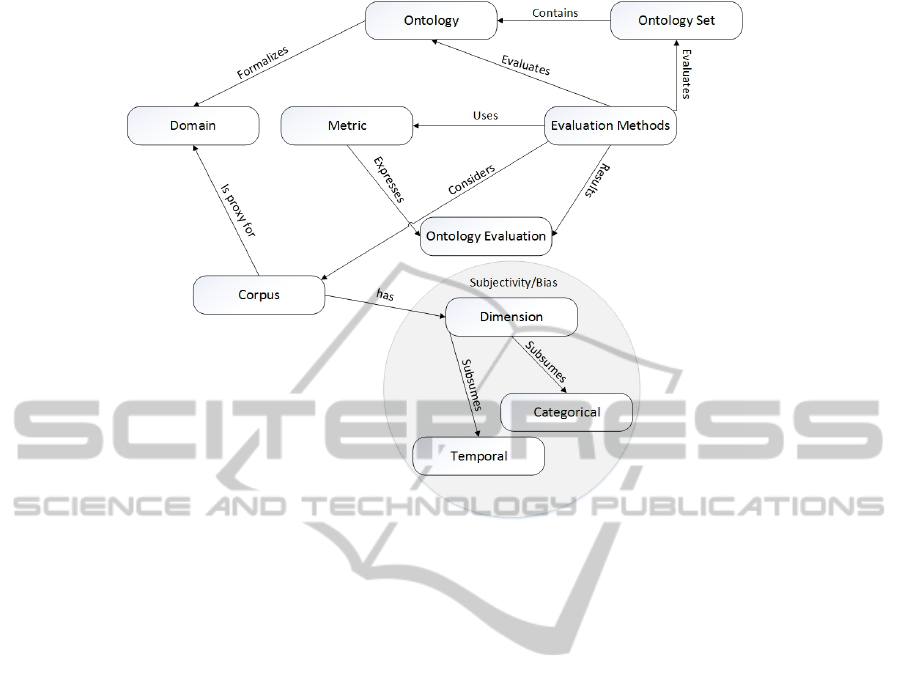

The framework presented in this paper which is rem-

iniscent of Vrandecic’s framework for ontology eval-

uation (Vrandecic, 2010) is depicted and summarized

in Figure 1. Sections 5 through 8 explain the fun-

damental components of this framework and provide

details on how they relate to each other. An ontol-

ogy (O) has been defined as a formal specification of

a domain of interest through the definition of the con-

cepts in the domain and the relationships that hold

between them. An ontology set (S) is a collection

of ontologies, ∃O ∈ S. Evaluation methods evaluate

an ontology or a set of ontologies. For the purposes

of a data-driven approach to ontology evaluation, the

evaluation is conducted from the viewpoint of a do-

main corpus. Put simply, evaluation methods evaluate

ontologies against the domain corpus by using met-

rics and their measures to measure the correctness or

quality of the ontologies. In other terms, an ontology

evaluation which is the result of the application of an

evaluation methodology, is expressed by metrics. In a

data-driven ontology evaluation undertaking, the do-

main corpus is a proxy for the domain of interest. We

argue that this proxy is non-static and changes over

several dimensions including the temporal, categori-

cal, etc. These dimensions are argued to be the bias

factors and this work endeavours to explore their in-

fluence on ontology evaluation.

5 THE CORPUS

Current research in data-driven ontology evaluation

assume that domain knowledge is constant. Hence,

the premise of this paper:

Premise

Literature has suggested that an ontology (a model of

domain knowledge) represents the domain in the con-

text of the time, place, and cultural environment in

which it was created as well as the modeller’s per-

ception of the domain (Brank et al., 2005; Brewster

et al., 2004). We argue that this extends to domain

knowledge. Domain knowledge or concepts are dy-

namic and change over multiple dimensions includ-

ing the temporal, spatial and categorical dimensions.

There has been recent attempts to formalize this in-

herent diversity, for example, in the form of a knowl-

edge diversity ontology (Thalhammer et al., 2011).

We therefore, argue that any evaluation based on a

corpus should then do it over these dimensions. This

is something that has been overlooked by current re-

search on data-driven ontology evaluation.

5.1 Temporal

As previously mentioned, information about a domain

can be discussed on its temporal axis. This is espe-

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

58

Figure 1: A Theoretical Framework for Data-driven Ontology Evaluation that identifies and accounts for subjectivity.

cially true from an academic viewpoint. For example,

in the workflow management domain, current provi-

sions are constantly compared in research undertak-

ings with new concepts and languages proposed as

solutions to gaps (Van Der Aalst et al., 2003). The

word current suggest a form of timeline; what was

current a decade ago is today considered in historic

terms as things evolve over time. For example, in the

early years of workflow management, the focus was

mostly on office automation (Lusk et al., 2005). How-

ever, from the early 2000s, the focus shifted towards

the formalization of business processes in the form of

workflow languages. These variabilities would be re-

flected in the documents about the domain, also re-

ferred to as the corpus. Hence, one would be in-

clined to deduce that there would be a better congru-

ence between a current ontology pitted against a cur-

rent corpus than there would be for an older ontology.

This congruence would suggest that if the ontology

requires a lot of revision then the congruence suggests

some form of distance between domain corpora and

the ontology.

5.2 Categorical

Closely related to the temporal dimension is the cate-

gorical dimension. While the temporal would show a

diachronic evaluation of an ontology’s coverage of the

domain, the categorical suggests the partitioning of

the domain corpus into several important subject ar-

eas. Taking the example of the workflow management

domain again, it can be partitioned into many differ-

ent subjects of interest. At the top level you would

consider such topics as workflow in business, scien-

tific workflows, grid workflows all within the um-

brella of “workflow” but with differing requirements,

environments and operational constraints. At another

level of granularity you could consider such topics as

business process modelling, workflow patterns, and

workflow management tools.

Often ontologies are used not in the applications

they were intended for. For example, a workflow on-

tology created to describe collaborative ontology de-

velopment (Sebastian et al., 2008) could be plugged

into a simple workflow management system since it

has the notions of task and task decomposition. How-

ever, the distance between the ontology as a model of

the domain and the different categories of the domain

need investigation.

6 ONTOLOGIES

An ontology is shared approximate specification of a

domain. This implies some sort of distance between

the ontology and the domain, hence, the need for eval-

uation. In the context of the proposed framework, an

evaluation undertaking involves one or more ontolo-

gies.

Data-drivenDiachronicandCategoricalEvaluationofOntologies-Framework,Measure,andMetrics

59

7 THE METRIC OF INTEREST

In the case of evaluating an ontology or a set of on-

tologies in the view of a corpus, we put forward that

the coverage measure is the most relevant. This may

not have been stated explicitly in current research on

data-driven ontology evaluation, however, we have

observed this to be the case. This is more obvious

in the account given by (Brewster et al., 2004) in ref-

erencing their creation of the Artequakt application

(Alani et al., 2003). Their purpose was to evaluate

their ARTEQUAKT ontology along side four other

ontologies in the view of a corpus by measuring the

congruence between the ontologies and the selected

corpus. Congruence here is defined as the ontology’s

level of fitness to the selected corpus (Brewster et al.,

2004). The evaluation consists of (i) drawing a vec-

tor space representation of both the domain corpus

(documents about the domain) and the ontology cor-

pus (concepts from the ontology), and (ii) calculating

the distance between the corpora in their case using

Latent Semantic Analysis. The result is a similarity

score, which in fact represents the ontology’s cover-

age of the domain. The same can be observed in one

of our recent works (Hlomani and Stacey, 2013) that

instantiates this approach to ontology evaluation.

Coverage is explicitly stated as a measure of in-

terest in (Ouyang et al., 2011) with respect to data-

driven ontology evaluation. Coverage in this work is

partitioned into the coverage of the ontology concepts

and the coverage of ontology relations with respect to

a corpus. This work also considers the cohesion and

coupling metrics, none of which has any bearing on

corpus evaluation.

In this regard, if domain knowledge is multi-

dimensional and if coverage is the measure that eval-

uates the congruence between an ontology or set

of ontologies and domain knowledge then, coverage

should be measured with respect to the dimensions

of the corpus. Hence, this work’s proposed metrics

(temporal bias and category bias).

8 METHODS

Methods or methodologies are the particular proce-

dures for evaluating the ontologies within the con-

text of an evaluation framework. With respect to the

data-driven ontology evaluation and this paper’s pro-

posed framework, a method calculates the measure of

a given metric in the view of a given corpus. As an

example, a methodology will measure the coverage

(metric) of a set of workflow ontologies or a single

ontology based on a workflow modelling corpus.

One method for evaluating an ontology’s cover-

age of a corpus as suggested by Brewster and his col-

leagues is that of decomposing both the corpus and

ontology into a vector space (Brewster et al., 2004).

This then allows for distances or similarity scores be-

tween the two corpora to be calculated. Similar exper-

imentation was conducted by (Hlomani and Stacey,

2013) and other variations of these have been docu-

mented in the literature, e.g. (Ouyang et al., 2011).

Latent semantic analysis has been a common tech-

nique used for this purpose. Tools have been devel-

oped that implement these structures such as the Text

Mining Library (TML) by Villalon and Calvo (Vil-

lalon and Calvo, 2013) which was employed for the

experiments in this paper. TML is a software library

that encapsulates the inner complexities of such tech-

niques as information retrieval, indexing, clustering,

part-of-speech tagging and latent semantic analysis.

9 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

There are two main hypotheses to this approach

each pertaining to a respective dimension. For each

hypothesis, there exists the Null Hypothesis (H

0

).

Temporal Bias

1. Null Hypothesis (H

0

): If the domain corpus

changes over its temporal dimension, then the

ontology’s coverage of the domain remains the

same.

2. Alternate Hypothesis (H

1

): If the domain corpus

changes over its temporal dimension, then the on-

tology’s coverage of the domain changes along

the same temporal dimension.

Category Bias

1. Null Hypothesis (H

0

): If the domain corpus

changes over its categorical dimension, then the

ontology’s coverage of the domain remains the

same.

2. Alternate Hypothesis (H

1

): If the domain corpus

changes over its categorical dimension, then the

ontology’s coverage of the domain changes.

9.1 Procedure

The main steps of each experiment are outlined in

Procedure 1.

Step 1 Ontologies: The ontologies used for experi-

mentation are listed in Table 1.

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

60

Table 1: Profiles of the ontologies in the pool.

Ontology Size Focus Year Created

BMO 700+ Business Process Management 2003

Process 70+ Web Services 2007

Work f low 20+ Collaborative Workflow -

Intelleo 40+ Learning and Work related Workflows 2011

Procedure 1: Experimental procedure.

1. Select the ontologies to be evaluated from the on-

tology pool

2. Select the documents to represent the domain

knowledge (corpus)

3. Repeat step 2 for each dimension

4. Calculate the similarity between the ontologies

and the domain corpus

5. Perform statistical evaluation

6. Repeat steps 4 and 5 for each ontology

Step 2. Document Selection: There were three main

things that were considered in the selection of the

corpus: (i) The source: here we considered three

main databases (IEEE, Google Scholar, and ACM);

(ii) Search terms: we used the Workflow Management

Coalition (WFMC) as a form of authority and used

its glossary and terminology as a source for search

terms. Ten phrases were randomly selected; (iii) Re-

strictions: in defining the corpora, bias is simulated

by means of restricting desired corpora by date (for

the date bias, refer to Table 2) and subject matter (for

the category bias, refer to Table 3).

Table 2: Corpus definition for experiment #1 showing date

brackets and number of documents for each bracket as well

as quantity of documents retrieved from each repository.

Bracket Per Repository

Google IEEE ACM Sum

[1984···1989] 1/3 1/3 1/3 24

[1990···1995] 1/3 1/3 1/3 24

[1996···2001] 1/3 1/3 1/3 24

[2002···2007] 1/3 1/3 1/3 24

[2008···2014] 1/3 1/3 1/3 24

Sum 120

Step 4. Calculate similarity between ontology and

corpora. Calculate the cosine similarity between each

document vector X

1

and each ontology X

2

as follows:

similarity(X

1

,X

2

) = cos(θ) =

X

1

· X

2

k X

1

k ∗ k X

2

k

Table 3: Corpus definition for experiment #2 showing key

phrases used for each corpus and number of documents for

each corpus. C

1

is Business Process Management, C

2

is

Grid Workflow, C

3

is Scientific Workflow.

Corpus Per Repository

Google IEEE ACM Sum

C

1

1/3 1/3 1/3 24

C

2

1/3 1/3 1/3 24

C

3

1/3 1/3 1/3 24

Sum 72

Step 5. Perform statistical evaluation. For each di-

mension we evaluate the ontology coverage measures

from two perspectives: (i) multiple ontologies (e.g.

we take each date bracket and evaluate how cover-

age of all the ontologies vary for the particular date

bracket); (ii) single ontology (e.g. we take an ontol-

ogy and evaluate how its coverage varies across the

different date brackets) and thus demarcate the exper-

iments as follows:

Date Bias Part 1: Multiple Ontologies (For each

bracket)

1. Compare the ontologies’ coverage for each

bracket against each other using nonparametric

statistics (Kruskal Wallis)

2. Do Post-Hoc analysis where there is significance:

n(n − 1)

2

= 6 pairwise comparisons (for each date

bracket)

Date Bias Part 2: Single Ontology

1. Difference between its coverage across date

brackets using nonparametric statistics (Kruskal

Wallis)

2. Do Post-Hoc analysis where there is significance:

n(n − 1)

2

= 10 pairwise comparisons (for each on-

tology)

The same structure is followed for the Category

Bias except instead of date brackets we define corpora

for the domain categories or subject areas.

Data-drivenDiachronicandCategoricalEvaluationofOntologies-Framework,Measure,andMetrics

61

Table 5: Post-hoc analysis: pairwise comparisons of the ontologies’ coverage of the domain between 1984 and 1989.

i

j

BMO Process Workflow Intelleo

Process p= 0.012

i = 36.38

j = 12.63

Workflow p= 0.036

i = 35.63

j = 13.38

p > 0.05

i = 18.25

j = 30.75

Intelleo p > 0.05

i = 35.88

j = 13.13

p > 0.05

i = 18.25

j = 30.75

p > 0.05

i = 26.92

j = 22.08

Table 4: Results for the evaluation of the difference between

the means of the four ontologies’ coverage of each bracket

using the Kruskal Wallis test.

Date Bracket P value Significant?

[1984 − 1989] 0.008358 yes

[1990 − 1995] 2.743e-12 yes

[1996 − 2001] 3.714e-10 yes

[2002 − 2007] 3.86e-09 yes

[2008 − 2014] 1.335e-07 yes

10 RESULTS

10.1 Date Bias - Part 1

Table 4 summarizes the results from the test between

the mean coverage of all the ontologies per bracket.

The table depicts the results of the statistical signif-

icance test of the difference between the mean cov-

erage of the BMO, Process, Workflow, and the In-

telleo ontologies per date bracket. The table shows

that at the α = 0.05 level of significance, there exists

enough evidence to conclude that there is a difference

in the median coverage (and hence, the mean cover-

age) among the four ontologies (at least one of them is

significantly different). In relating this to our tempo-

ral hypotheses, we would reject the Null Hypothesis

(H

0

) that ontology coverage remains the same if the

temporal aspect of domain knowledge changes. This

demonstrates the usage of the Temporal bias metric.

In contrast to current approaches where definitive an-

swers are given as to whether OntologyA is better than

OntologyB, we see a qualified answer to the same

question to the effect that OntologyA is better than

OntologyB only in these defined time intervals.

This test, however, does not indicate which of

the ontologies are significantly different from which.

Therefore, follow up tests were conducted to evaluate

pairwise differences among the different ontologies

for each date bracket. This also includes controlling

for type 1 error by using the Bonferroni approach.

10.2 Date Bias - Part 1: Post-Hoc

The post-hoc analysis results reveal which ontologies

as compared to the others have a significantly differ-

ent mean coverage for each of the data brackets. Ta-

ble 5 shows what appears to be a common theme with

regards to which ontology performed better than the

others. It shows that the BMO ontology’s mean cov-

erage is both larger (considering the mean ranks i and

j) and significantly different (p value < α) from the

other ontologies; hence we reject the null hypothesis

with regards to the BMO ontology. The table also

shows an exception to the earlier sentiments, and that

is in the case of the BMO compared to the Intelleo

ontology. In this case there is no statistical signifi-

cance in the difference between the mean coverage of

these ontologies. Therefore, at this time interval the

ontologies represented the domain similarly. The ta-

ble also appears to show another trend with regards

to the other ontologies as compared to their counter-

parts. Their P values are greater than the rejection

criteria (p value > α) and hence the null hypothesis is

accepted.

Table 5 shows only one of the date brackets, there

are four more of these but in the interest of space and

brevity we will only show results where there was sta-

tistical significance as depicted in Table 6.

10.3 Date Bias - Part 2

Table 7 shows that at the al pha = 0.05 level of sig-

nificance, there exists enough evidence to conclude

that there is a difference in the median coverage (and,

hence, the mean coverage) for each of the ontologies

coverage across the different date brackets. The dif-

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

62

Table 6: Pairwise comparisons of the ontologies’ coverage

for each date bracket.

Date Bracket Ontology Mean

Rank

P value

[1990-1995] BMO 36.38 0.00

Process 12.63

BMO 35.63 0.00

Workflow 13.38

BMO 35.88 0.00

Intelleo 13.13

Process 18.25 0.012

Workflow 30.75

Process 18.25 0.012

Intelleo 30.75

[1996-2001] BMO 35.79 0.00

Process 13.21

BMO 35.58 0.00

Workflow 13.42

BMO 35.75 0.00

Intelleo 13.25

[2002-2007] BMO 33.87 0.00

Process 13.13

BMO 33.09 6e-06

Workflow 13.91

BMO 34.09 0.00

Intelleo 12.91

[2008-2014] BMO 31.24 0.00

Process 11.76

BMO 30.19 2.4e-05

Workflow 12.8

BMO 30.05 3.6e-05

Intelleo 12.95

ference between the BMO’s coverage of at least one

of the date brackets is statistically significant. The

same applies to the other three ontologies (Process,

Workflow, and Intelleo) since their p values are less

that the α value (at 0.02007, 0.01781, and 0.03275,

respectively). In relating this to the temporal hypothe-

ses, we would reject the Null Hypothesis (H

0

) that on-

tology coverage remains the same if the temporal as-

pect of domain knowledge changes. This also demon-

strates the usage of the Temporal bias metric but only

considers each ontology for the different date brack-

ets. This gives perspective to an ontology evaluation

of a single ontology.

Like in the case of Experiment #1 Part 1, this test,

does not indicate which of the date brackets are sig-

nificantly different from which. Therefore, follow-up

tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences

among the different date brackets for each ontology.

This also includes controlling for type 1 error by us-

ing the Bonferroni approach.

Table 7: Results for the evaluation of the difference between

the means of each ontology’s coverage of the date brackets

using the Kruskal Wallis test.

Ontology P Value Significant?

BMO 0.01667 yes

Process 0.02007 yes

Work f low 0.01781 yes

Intelleo 0.03275 yes

10.4 Date Bias - Part 2: Post-Hoc

For each ontology, the post-hoc analysis results reveal

which date brackets as compared to the others have a

significantly different mean coverage. As an exam-

ple, this would answer questions like “How relevant

is a given ontology?” or “How does a given ontol-

ogy’s coverage vary with time?”. An answer to these

questions would then help in determining how rele-

vant the ontology is to current settings. If we look

at the results one ontology at a time, we observe the

following:

BMO ontology (refer to Table 8): In the case of

pairwise comparisons of the date brackets, there are

only two of the comparisons where there is statistical

significance in the difference between the mean cov-

erage. This is the case where the data bracket [1984-

1989] is compared to that of [1990-1995] and the

comparison between the [1984-1989] and the [1996-

2002] brackets. In both these cases, at the α = 0.05

we can reject the Null hypothesis (H

0

) and conclude

that the BMO ontology’s coverage of the domain does

vary with time at least for those time intervals (with

the p values < α at 0.04 and 0.02, respectively). In

this case we could conclude that BMO was better

suited for the domain between 1990 and 1995 as well

as between 1996 and 2001 than it was between 1984

and 1989. It does, however, cover the domain at the

other time intervals the same.

Table 8 also shows only one of the ontologies

there are three more of these but in the interest of

space and brevity we will only show results where

there was statistical significance as depicted in Table

9.

10.5 Category Bias - Part 1

Table 10 depicts the results of the statistical signifi-

cance test of the difference between the mean cover-

age of the BMO, Process, Workflow, and the Intelleo

ontologies per category (Business Process Manage-

ment, Grid Workflow, and Scientific Workflow). The

table shows that at the α = 0.05 level of significance,

there exists enough evidence to conclude that there

Data-drivenDiachronicandCategoricalEvaluationofOntologies-Framework,Measure,andMetrics

63

Table 8: Post-Hoc analysis for the BMO ontology across all date brackets.

i

j

[84-89] [90-95] [96-01] [02-07] [08-14]

[90-95] p = 0.04

i = 15.84

j = 26.88

[96-01] p = 0.02

i = 15.32

j = 27.29

p > 0.05

i = 23.13

j = 25.88

[02-07] p > 0.05

i = 17

j = 25.22

p > 0.05

i = 25.67

j = 22.26

p > 0.05

i = 26.58

j = 21.30

[08-14] p > 0.05

i = 16.89

j = 23.76

p > 0.05

i = 24.67

j = 21.10

p > 0.05

i = 25

j = 20.71

p > 0.05

i = 22.70

j = 22.29

Table 9: Pairwise comparisons of the date brackets for each

ontology.

Ontology Date Bracket Mean

Rank

P value

Process [1984-1989] 15.21 0.02

[1996-2001] 27.38

Workflow [1984-1989] 15.32 0.02

[1990-1995] 27.29

Intelleo [1984-1989] 16.11 0.06

[1990-1995] 26.67

is a difference in the median coverage (and, hence,

the mean coverage) among the four ontologies (at

least one of them is significantly different) for each

of the categories. However, this test does not indi-

cate which of the ontologies are significantly differ-

ent from which (or simply put, where the difference

lies). Therefore, follow-up tests were conducted to

evaluate pairwise differences among the different on-

tologies for each domain knowledge category. This

also includes controlling for type 1 error by using the

Bonferroni approach.

Table 10: Results for the evaluation of the difference be-

tween the means of the four ontologies’ coverage of each

Category using the Kruskal Wallis test.

Domain Category P Value Significant?

Business Process

Management

5.341e-09 yes

Grid Workflow 2.055e-08 yes

Scientific Workflow 4.364e-10 yes

10.6 Category Bias - Part 1: Post-Hoc

At an alpha (α) = 0.05, we can conclude that the BMO

ontology’s mean coverage is both larger (considering

the mean ranks) and significantly different (p value

< α) from the other ontologies across all the cate-

gories, hence we reject the Null hypothesis with re-

gards to the BMO ontology. In terms of the cate-

gory bias metric, it distinguishes the BMO ontology

as better representing the Business Process Manage-

ment Category of the Workflow domain (Table 11).

The same is seen to be true for the Grid Work-

flow Category and Scientific Workflow Category as

depicted in Table 12 which shows the pairwise com-

parison between the ontologies for the Grid Work-

flow and Scientific Workflow categories. This was

expected for the Business Process Management Cate-

gory considering that is the ontology’s area of focus.

The other ontologies, when pitted against each other

across the different domain categories seem to cover

the domain similarly.

10.7 Category Bias - Part 2

Table 13 summarizes the results from the test between

the mean coverage of each ontology across the five

domain categories. This reflects on how each ontol-

ogy’s coverage spreads through the partitions of the

domain as defined by the categories of this paper.

Considering these results we can conclude that for

all the ontologies at an α = 0.05 there is no signif-

icant statistical evidence to suggest that the ontolo-

gies cover the domain categories differently. For the

case of the BMO ontology, the observed results are

contrary to what we had expected since the ontology

was predicated on the Business Process Management

category of the workflow domain and therefore, you

would have expected a slight bias towards the same

category. We could attribute this observation to the

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

64

Table 11: Post-Hoc analysis for the Business Process Management Category.

i

j

BMO Process Workflow Intelleo

Process p < 0.05

i = 32.55

j = 12.45

Workflow p= 6e − 06

i = 32.18

j = 12.82

p > 0.05

i = 19.32

j = 25.68

Intelleo p < 0.05

i = 32.45

j = 12.55

p > 0.05

i = 20.00

j = 25.00

p > 0.05

i = 23.23

j = 21.77

Table 12: Pairwise comparisons of the ontologies for each

category.

Category Ontology Mean Rank P value

Grid

Workflow

BMO 28.58 0.00

Process 10.42

BMO 28.58 0.00

Workflow 10.42

BMO 28.42 6e-06

Intelleo 10.58

Scientific

Workflow

BMO 34.17 0.00

Process 12.83

BMO 34.39 0.00

Workflow 12.61

BMO 34.83 0.00

Intelleo 12.17

size of the ontology. You could argue that it contains

a large enough number of concepts to blur the lines

between the defined categories.

Table 13: Results for the evaluation of the difference be-

tween the means of each ontology’s coverage of the domain

categories using the Kruskal Wallis test.

Ontology P Value Significant?

BMO 0.1142 no

Process 0.9869 no

Work f low 0.2025 no

Intelleo 0.4836 no

11 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

Section 4 discusses a theoretical framework that ad-

vocates for qualifying the results of data-driven ontol-

ogy evaluation and thereby accounting for bias. This

has further been demonstrated through experimenta-

tion in Section 9. When the results are unqualified

as was the case in Brewster et al. (Brewster et al.,

2004), important information (e.g. the ontology is ag-

ing) remain hidden and its relevance pertaining to do-

main knowledge is undiscovered. A diachronic eval-

uation allows for such information to be uncovered.

For example, between 1984 and 1989 there was no

significant difference in the coverage of the workflow

domain by the Process ontology as compared to the

Workflow ontology. However, there was a difference

in the period 1990 to 1995. This would suggest some

change to domain knowledge between those time in-

tervals (e.g. introduction of new concepts). This dif-

ference would not be accounted for if domain knowl-

edge is not partitioned accordingly during data-driven

ontology evaluation.

12 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has discussed an extension to data-driven

ontology evaluation where the main point of discus-

sion was a theoretical framework that accounts for

bias in ontology evaluation. This is a framework that

is premised on the notion that an ontology is a shared

conceptualization of a domain with inherent biases

and as well as that domain knowledge is non-static

and evolves over several dimensions such as the tem-

poral and categorical. The direct contributions of this

work include the two metrics (temporal bias and cat-

egorical bias), the theoretical framework, as well as

an evaluation method that can serve as a template for

the definition of evaluation methods, measures, and

metrics.

It is fairly obvious that ontology evaluation consti-

tutes a broad spectrum of techniques each motivated

by several things such as goals and reasons for evalua-

tion as has been show in this paper. The framework of

this paper is directed to users and researchers within

Data-drivenDiachronicandCategoricalEvaluationofOntologies-Framework,Measure,andMetrics

65

the data-driven ontology evaluation domain. It serves

to fill the gap within this domain where time and cat-

egory contexts have been overlooked.

REFERENCES

Alani, H., Sanghee, K., Millard, E. D., Weal, J. M., Hall,

W., Lewis, H. P., and Shadbolt, R. N. (2003). Auto-

matic ontology-based knowledge extraction from web

documents. Intelligent Systems, IEEE, 18(1):14–21.

Brank, J., Grobelnik, M., and Mladeni

´

c, D. (2005). A sur-

vey of ontology evaluation techniques. In Proceedings

of the Conference on Data Mining and Data Ware-

houses (SiKDD 2005), pages 166–170.

Brewster, C., Alani, H., Dasmahapatra, S., and Wilks, Y.

(2004). Data-driven ontology evaluation. In Proceed-

ings of the 4th International Conference on Language

Resources and Evaluation, Lisbon, Portugal.

Burton-Jones, A., Storey, C. V., Sugumaran, V., and

Ahluwalia, P. (2005). A semiotic metrics suite for as-

sessing the quality of ontologies. Data & Knowledge

Engineering, 55(1):84 – 102.

Hlomani, H. and Stacey, A. D. (2013). Contributing evi-

dence to data-driven ontology evaluation: Workflow

ontologies perspective. In Proceedings of the 5th

International Conference on Knowledge Engineering

and Ontology Development, Vilamoura, Portugal.

Lusk, S., Paley, S., and Spanyi, A. (2005). The evolution of

business process management as a professional disci-

pline. In Evolution of BPM as a Professional Disci-

pline. BPTrends.

Nonaka, I. and Toyama, R. (2005). The theory of

the knowledge-creating firm: subjectivity, objectiv-

ity and synthesis. Industrial and Corporate Change,

14(3):419–436.

Ouyang, L., Zou, B., Qu, M., and Zhang, C. (2011). A

method of ontology evaluation based on coverage, co-

hesion and coupling. In Fuzzy Systems and Knowl-

edge Discovery (FSKD), 2011 Eighth International

Conference on, volume 4, pages 2451 –2455.

Patel, C., Supekar, K., Lee, Y., and Park, E. K. (2003). On-

tokhoj: A semantic web portal for ontology search-

ing, ranking and classification. In In Proc. 5th ACM

Int. Workshop on Web Information and Data Manage-

ment, pages 58–61.

Sebastian, A., Noy, N., Tudorache, T., and Musen,

M. (2008). A generic ontology for collaborative

ontology-development workflows. In Gangemi, A.

and Euzenat, J., editors, Knowledge Engineering:

Practice and Patterns, volume 5268 of Lecture Notes

in Computer Science, pages 318–328. Springer Berlin

/ Heidelberg.

Spyns, P. (2005). EvaLexon: Assessing triples mined from

texts. Technical Report 09, Star Lab, Brussels, Bel-

gium.

Thalhammer, A., Toma, I., Hasan, R., Simperl, E., and

Vrandecic, D. (2011). How to represent knowledge

diversity. Poster at 10th International Semantic Web

Conference.

Van Der Aalst, W. M. P., Ter Hofstede, A. H. M., Kie-

puszewski, B., and Barros, A. P. (2003). Workflow

patterns. Distrib. Parallel Databases, 14(1):5–51.

Villalon, J. and Calvo, R. A. (2013). A decoupled architec-

ture for scalability in text mining applications. Journal

of Universal Computer Science, 19(3):406–427.

Vrandecic, D. (2010). Ontology Evaluation. PhD the-

sis, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Ger-

many.

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

66