Knowledge Creation in Technology Evaluation of 4-Wheel Electric

Power Assisted Bicycle for Frail Elderly Persons

A Case Study of a Salutogenic Device in Healthcare Facilities in Japan

Miki Saijo

1

, Makiko Watanabe

2

, Sanae Aoshima

3

, Norihiro Oda

3

,

Satoshi Matsumoto

4

and Shishin Kawamoto

5

1

Graduate School of Innovation Management, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan

2

Graduate School of Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science, Chiba, Japan

3

Kakegawa Kita Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan

4

Corporate Planning Division, Yamaha Motor Engineering Co., Ltd, Shizuoka, Japan

5

Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

Keywords: Knowledge Creation, Tacit Knowledge, Health Care for Frail Elderly Persons, AT Devices, Technology

Evaluation.

Abstract: As societies age, it is anticipated that we will see a sudden increase in the number of frail elderly persons.

New assisted-technology (AT) devices to facilitate the activities of daily life (ADL), especially of walking,

are essential for the healthy life of these people. However, frail elderly people suffer a variety of physical

and mental weaknesses that tend to hinder their ability to make use of AT devices in the intended manner.

Because of this, it is important that new AT devices undergo technology evaluation within the context in

which they are to be used, but there is very little research in this area. In this study, frail elderly people in

Japanese daycare centers and rehabilitation facilities were given a 4-wheel, power-assisted bicycle, called a

“Life Walker” (LW), to ride, and technology evaluations were carried out based on functionality, usability,

and experience as perceived by the frail elderly riders. The LW is considered to be best suited for those age

75 and older assessed at level 1 to 3 under Japan’s long-term care insurance program, but the data for the 61

people at the rehabilitation facility who tried out the bicycle under the supervision of a resident physical

therapist (PT), indicated that there was considerable individual deviation on the continued use of the AT

device. The LW is also meant to enable frail elderly users who have difficulty walking to go outside and

enjoy themselves more. It was found, however, that this effect was achieved only when the physical

therapist intervened, gave encouragement, adjusted the bicycle settings as needed for the user, and otherwise

created new knowledge. It was also found that in order for this kind of knowledge creation to take place, the

bicycle must be used in an appropriate setting, the user needs to have a proactive attitude, and organizational

support to ensure that therapists are appropriately assigned is necessary.

1 INTRODUCTION

Between 2000 and 2050, the proportion of the

world’s population over 60 years will double from

around 11% to 22%. The absolute number of people

aged 60 years and over is expected to increase from

605 million to 2 billion over the same period (WHO,

2014). Japan is aging rapidly also. The population of

people 75 years or older will double over the next

two decades (Fukutomi et al, 2013), and the national

cost for medical care for those 70 years or older will

account for 45% (MHLW, 2011) of all medical cost.

Health promotion for this large cohort of aging

population is indispensable for building a

sustainable society.

Our perception of health has gradually changed

from a dichotomous to a salutogenic perspective. In

the former, health and disease are treated separately

and health is defined as being “low on risk factors”.

The latter, however, focuses on “keeping people

well”. From this perspective, health is viewed as an

ease/dis-ease continuum (Antonovsky, 1996). The

1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion marks

one of the starting points of this change. Before the

87

Saijo M., Watanabe M., Aoshima S., Oda N., Matsumoto S. and Kawamoto S..

Knowledge Creation in Technology Evaluation of 4-Wheel Electric Power Assisted Bicycle for Frail Elderly Persons - A Case Study of a Salutogenic

Device in Healthcare Facilities in Japan.

DOI: 10.5220/0005136100870097

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 87-97

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

charter was drafted, it was considered the

individual’s responsibility to maintain a healthy

lifestyle, but under the Ottawa Charter, health is

something to be achieved through a collaboration of

environment, community, personal skills, and public

policies. The Ottawa Charter initiated a redefining

and repositioning of institutions, epistemic

communities and actors within the disease-health

continuum (Kickbusch, 2003).

Frail elderly persons, especially those aged over

75 years, who tend to be the main users of aged care

services live in a dis-ease condition. Frailty is highly

prevalent in old age and poses a high risk of falls,

disability, hospitalization, and mortality (Fried et al,

2001). Falls are common and often devastating

among older people (Rubenstein, 2006). Walking is

a risk factor for falling, and yet walking is a basic

salutary factor in an individual’s life. Therefore, in

order to promote health among frail elderly persons,

optimal approaches involving interdisciplinary and

inter-agency collaboration are required to build an

environment in which such people can go out

without worry about falling.

While some people may have difficulty in

walking, they may still be able to ride a bicycle.

Already there are electric power-assisted bicycles on

the market that will allow the rider to climb steep

hills with ease, even if they do not have much foot

power. The power-assisted bicycles were originally

developed by the Yamaha Motor Company. The 4-

wheel assisted bicycle is a newly developed vehicle

which is safer than walking for frail elderly persons,

and is actually allowed on public roads as a

wheelchair. Its controls are set so that it will not

exceed a speed of 6 km per hour when going

downhill. With this vehicle, a person who cannot

walk can climb a hillside at the same pace as

someone walking at normal speed. Though

technically it is already available, this vehicle is not

yet on the market because there remain concerns of

its safety for frail elderly users.

In order to find salutogenic benefits in lifestyles

of the frail elderly, we undertook action research on

frail elderly people’s use of this 4-wheel electric

power assisted bicycle in a rehabilitation hospital in

the city of Kakegawa, Japan. As Antonovsky (1996)

said, we must start with the question, “How can this

person be helped to move toward greater health?”

This kind of effort must relate to all aspects of the

person, and the frail elderly adult is no exception.

We tackled this question through interdisciplinary

and inter-agency collaboration among manufacturer,

hospital, municipal government, and university.

2 LITEATURE REVIEW

2.1 Assessing Frailty in Elderly Persons

In order to provide appropriate care for frail elderly

persons covered by long-term care insurance (LTCI)

the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and

Welfare (MHLW) drew up a Kihon Checklist, a

basic health checklist, for those aged 65 and older, to

be used as a frailty index to predict the risk of

requiring care under LTCI. The checklist consists of

a 25-item, self-reported questionnaire, covering

seven categories including physical strength,

nutritional status, and oral function, as well as

houseboundness, mobility, cognitive function, and

depression risk (Fukutomi et al, 2013). Using this

checklist, municipal governments classify the frail

elderly persons in their communities according to

their need for preventive care. Kakegawa City

covers all 25 items on the questionnaire as well as

medical certificates to identify the frail elderly.

Figure 1 is a partial view of the checklist and its

screening criteria.

Municipal governments use the basic checklist as

a guide to decide their own criteria and procedures

for preventive care and care services, the dispatch of

helpers, the lending of wheelchairs, and the need to

provide rehabilitation. Care services are provided in

accordance with the degree to which acitivities of

daily life (ADL) have deteriorated. Table 2 shows

the assesement levels for LTCI. Persons classfied as

Support Level 1 and Support Level 2 are eligible for

preventive care. Table 2 was drawn up by the first

author as a simplified illustration of Japanese LTCI

assessment levels.

A few researchers have evaluated the validity of

this checklist to predict the risk of requiring care

(Fukutomi et al, 2013; Tomata et al, 2011).

Fukutomi, 2013, in particular, has suggested that

physical strength and cognitive function are more

useful indices for detecting the risk of future

deterioration of ADL. However, there is no

consideration of intervention to prevent future risk.

Frailty is defined as a clinical syndrome in which

three or more of the following criteria are present:

unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion,

weakness (grip strength), slow walking speed, and

low physical activity (Fried, 2001). Geriatric

interventions have been developed to improve

clinical outcomes for frail older persons (Applegate

et al, 1990; Rubenstein, 2006). Maki et al, 2012, also

evaluated the efficacy of intervention by examining

a municipality-led walking program for the

prevention of mental decline in the elderly aged

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

88

72.0±4.0, in a randomized controlled trial. This

study introduced a 90-minute intervention program

consisting of 30 minutes of exercise and 60 minutes

of group work, and concluded that this intervention

program may provide benefits for some aspects of

cognition. Though their research target was not the

frail elderly, from the criteria in Table 1 and the

assessment level of LTCI we can easily surmise that

the frail elderly requiring LTCI are unable to

participate in this kind of walking intervention.

In these studies, some interventions were

implemented to evaluate the efficacy for improving

clinical outcome through randomized controlled

trials (RCT). Though RCT is a traditional evidence-

based methodology to examine the efficacy of

medical treatments or interventions in medicine, it

does not address the fact that frailty involves

multiple deteriorations, or that an elderly person’s

ability to take part in an intervention will vary

according to the context in which they live.

We need other methodologies to assess the

frailty of the elderly and to mitigate the

inconveniences in their daily life.

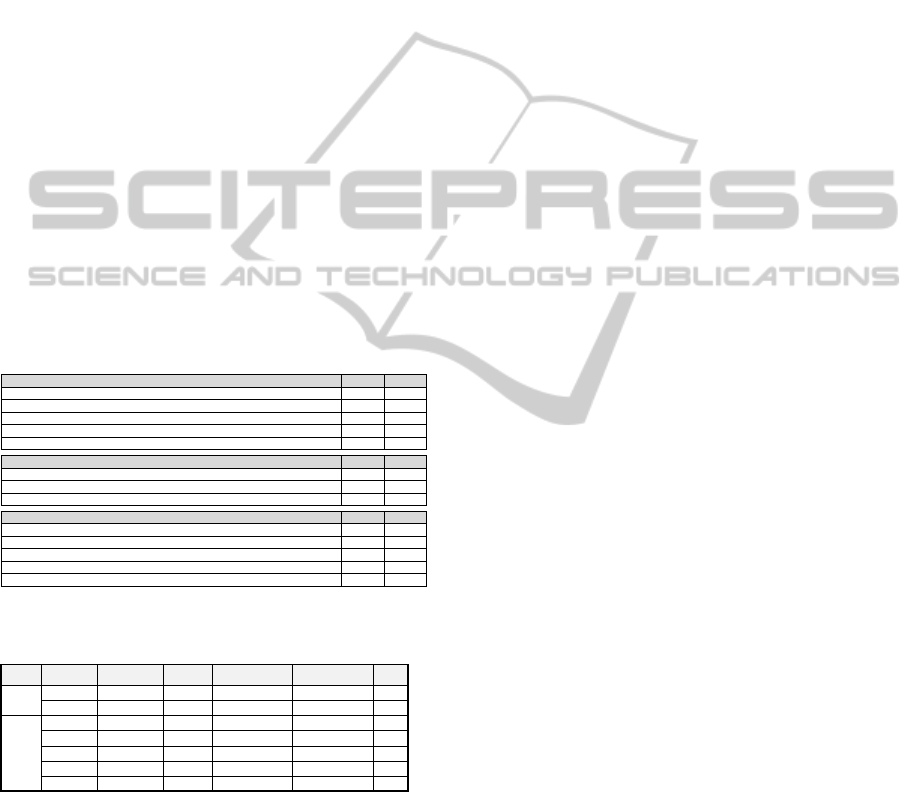

Table 1: Screening criteria for providing preventive care

(partial view of MHLW check list).

Mobility (those with top score of 3 points are candidates for preventive care) 0 point 1 point

Q6. Can you climb stairs without holding onto a handrail or wall? Yes No

Q7. Can you stand up from a sitting position without holding on to anything? Yes No

Q8. Can you walk continuously for 15 minutes? Yes No

Q9.Have you fallen within this one year? No Yes

Q10. Do you worry about falling down? No Yes

Cognitive functions (1 point or more required) 0 point 1 point

Q18. Do people around you say you repeat the same thing and have become forgetful? No Yes

Q19. Do you make phone calls by yourself? Yes No

Q20. Do you find yourself not knowing today’s date? No Yes

Depression (2 points or more required) 0 point 1 point

Q21. I do not feel any fulfillment in my daily life during the last two weeks. No Yes

Q22. I cannot enjoy things I used to enjoy during the last two weeks. No Yes

Q23. During the last two weeks, I am not willing to do what I could do easily before. No Yes

Q24. During the last two weeks, I do not feel I am useful to anyone. No Yes

Q25. During the last two weeks, I feel I am exhausted without any reason. No Yes

Table 2: Japan’s long-term care insurance assessment

levels (

△

○Yes, Partial, ×No).

Level Self-sufficient Body care Comprehension Behavior controlMobil

e

Support

Level 1

○

ᇞ

○ ○ ○

Level 2

○ ᇞ

ᇞ

○ ○ ○

L

TC

Level 1

ᇞ ᇞ

○ ○ ○

Level 2

ᇞ ᇞ

○ ○

ᇞ

Level 3

× ×

ᇞ ᇞ ᇞ

Level 4

× × × ×

ᇞ

Level 5

× × × × ×

2.2 Health Care in Tacit Knowledge

Since the 1970s, people have been given more room

to take the initiative in roles where they provide

expertise and participate in informing, ideating, and

conceptualizing activities in the early design phases

(Sanders and Stappers, 2008). This movement is

called user-centered design. For frail elderly people,

there are various assisted-technology (AT) devices

such as canes, walkers, and bath benches, as well as

wheelchairs, that could be considered to be user-

centered designs. As Mann et al (1999) notes, many

elderly persons rely on these devices.

NHS (the UK department of health) advocates

patient-led care and urges health care teams to move

from a service that does things to and for its patients

to one which is patient-led and which works with

patients to support them with their health needs

(Pickles, J., Hide, E., and Maher, L., 2008). AT

devices are provided to frail elderly people on the

assumption that the devices will promote their

independence and lower costs (Mann et al, 1999),

but there is little research on how much and what

kinds of frailty are mitigated by AT devices and

what kind of support is needed to make full use of

such devices. As some of the studies have pointed

out, an important part of health care consists of tacit

knowledge.

A significant part of health-care knowledge

exists in tacit form, for instance the working

knowledge of health care experts (Abidi, Cheah,

Curran, 2005). Abidi, Cheah, Curran, 2005, classify

tacit knowledge into 1) basic tacit knowledge or

routine experiential knowledge, and 2) complex tacit

knowledge or intuitive experiential knowledge. The

latter is “progressively accumulated as the expert

responds to atypical and high acuity clinical

problems–it is deeply embedded and, hence, not

easily articulated, yet manifests as the expert’s

intuitive judgment in challenging clinical situations.”

According to this classification, a health care

professional’s judgment of the usability of an AT

device for the frail user is inherent in the

professional’s tacit knowledge. The question is:

How can we extract this individual knowledge and

create new knowledge for patient-led care?

2.3 Knowledge Creation and

Technology Evaluation of AT

Devices

Knowledge creation starts with socialization, which

is the process of converting new tacit knowledge

through shared experiences in day-to-day social

interaction (Nonaka and Toyama, 2003). Nonaka

and Toyama also state that “knowledge creation is a

synthesizing process through which an organization

interacts with individuals, transcending emerging

contradictions that the organization faces”, and “one

can share the tacit knowledge of others through

shared experience” (Nonaka and Toyama, 2003). In

order to transform tacit knowledge to shared new

knowledge, socialization and efforts to transcend

KnowledgeCreationinTechnologyEvaluationof4-WheelElectricPowerAssistedBicycleforFrailElderlyPersons-A

CaseStudyofaSalutogenicDeviceinHealthcareFacilitiesinJapan

89

contradictions are needed. In professional health

care work places, medical doctors, nurses,

physiotherapists, and occupational therapists work

together. In this sense their routines consist of an

inter-agency, interdisciplinary collaborative

experience (Saijo et al, 2013). Also the main

contradictions in elderly health care are inherent in

the care itself. All human beings must eventually die,

but the care professional’s work is to challenge this

destiny. The need to transcend emerging

contradictions and shared experience are embedded

in their routines. The problem is how to elucidate

their tacit knowledge and reconstruct it to create new

knowledge. In this study, we describe this process

through a technology evaluation of a newly

developed 4-wheel electric power-assisted bicycle,

called a Life Walker or LW vehicle, for frail elderly

persons. This requires, however, that the health care

professional collaborate with outsiders, engineers

and researchers, to undertake the technology

assessment of the newly developed AT device.

Collaboration with outsiders requires socialization of

their mind or manners. We assume that this shared

new experience will extract their tacit knowledge to

create new knowledge in the methodology of caring

for frail elderly persons.

Technological evaluations of manual and

powered wheelchairs have already been made in the

field of anthropometry, the measurement of physical

characteristics and abilities of people (Paquet and

Feathers, 2004; Das and Kozey, 1999), with the

objective of acquiring information that is essential

for the appropriate design of a wheelchair. There is

little study, however, of the usability of a wheelchair,

or how it is actually used in real-world health care

circumstances. And there is no user-centered

technology evaluation of newly developed AT

devices for supporting the frail elderly on outings in

real-life circumstances with inter-agency and

interdisciplinary cooperation.

McNamara and Kirakowski (2005, 2006)

propose three aspects that need to be considered

from the viewpoint of user-centered technology

evaluation, namely, functionality, usability, and

experience. They state that these are unique but

independent aspects of usage. Functionality focuses

on the product and is evaluated by answering the

question, “What will the product do?” Usability is

defined by the ISO 9241-11 definition of usability as,

“the extent to which a product can be used by

specified users to achieve specified goals with

effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a

specified context of use” (ISO 9241). Experience is

the individual’s personal experience of using the

device. The question asked here should perhaps be,

“How do I relate to this product?”

In this study of the Life Walker (LW), we apply

these aspects of technology evaluation to the

framework of knowledge creation. The aim of this

study is to elucidate the process of knowledge

creation among inter-agency and interdisciplinary

health care professionals, engineers, and researchers

in evaluating AT technology meant to promote

patient-led care among frail elderly persons.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research questions

In introducing the Life Walker (LW), a

microcomputer-controlled, 4-wheel, electric power-

assisted bicycle, to frail elderly persons certified as

requiring care in a rehabilitation hospital and a

daycare center for the elderly, we began with two

questions: (1) What conditions are necessary to have

an LW used in a hospital or daycare setting in such a

way that there will be knowledge creation, and (2)

How can the functionality, usability, and experience

of the LW be measured quantitatively and

qualitatively? The three categories in the second

question were further broken down into additional

questions as follows:

Functionality: What are the distinguishing

characteristics of the LW and what kind of

elderly person is it best suited for?

Usability: What kind of elderly person will ride

the vehicle and for how long?

Experience: What do the elderly persons and

care professionals experience through riding the

LW?

3.2 Case Study Method

We loaned the LW for two months to a rehabilitation

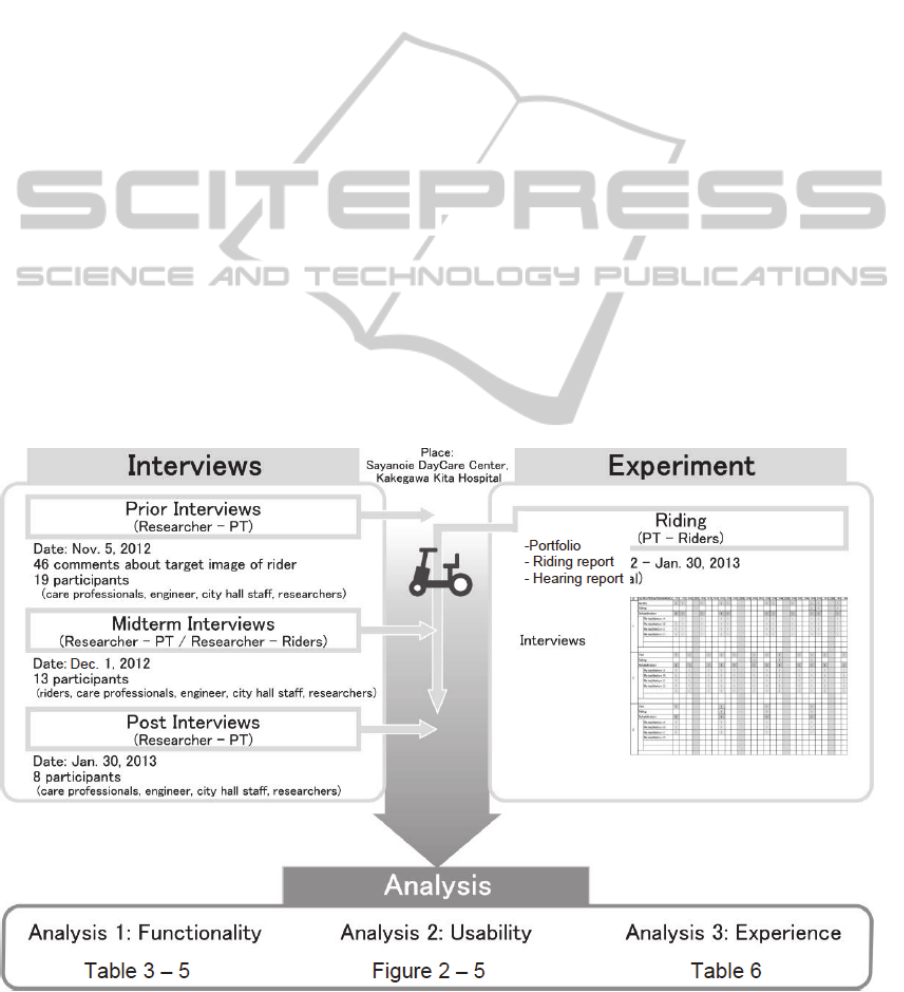

hospital and a daycare center for the elderly. Figure

1 shows the flow of data collection for this study.

• Period: Nov 5, 2012 to Jan 30, 2013

• Targets: 1) Frail elderly people (hereafter

“facility users”) in the Kakegawa Kita Hospital

and the Kakegawa City Sayanoie daycare facility

for the elderly. Facility users were rated at

Support Level 1 through LTC 4 level ; and

2) Hospital and daycare care professionals:

physiotherapists (PT), occupational therapists

(OT), care managers (CM), care workers (CW),

and social workers (SW)

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

90

• Methods: Questionnaire survey, test riding of

LW, and interviews of care professionals

The questionnaire for this study included the

following kinds of information. The authors

prepared a form that was filled out by the care

professionals (as it turned out, only PTs in the

rehabilitation hospital filled out the form). Also we

interviewed care professionals at both hospital and

daycare center.

Personal portfolio: Age, sex, care rating, dates at

facility, experience riding LW, type of

rehabilitation, continuing or interruption of LW

experience: PT’s predictions of whether each

facility user will become a continuing rider or

not.

Riding report: Rider’s basic checklist (if there

were multiple test rides, only changes from the

first ride were recorded), reason for test rides,

evaluation of driving skills

Recording of interview: The authors carried out

focus group interviews (FGI) of the care

professionals just before or after the loan of the

LWs and during the loan period.

The sub-categories of the research questions

were handled as follows.

3.2.1 Functionality

Functionality is a concept related to the technical

aspects of a product, and involves answering the

question, “What does the product do?” (McNamara

and Kirakowski, 2005, 2006)

The specifications of the LW vehicle used in this

study are as follows.

・Overall length x Overall width x Overall height:

1.190 mm x 655 mm x 990 mm

・Dry weight (with battery): 36 kg (38 kg)

・Tires: Sponge-type; do not blow out

・Drive system: dual electric-assisted run and full-

electric run

・ Control system: Microcomputer control with

motor controlled automatic brake

・Max forward speed: 6.0 km/h

・Max reverse speed: 0.5 km/h

When the rider is a healthy adult, the functions of

the vehicle are dependent on its specifications; while

there may be small divergences, the functions of the

vehicle do not change drastically among different

riders. The functionality of this vehicle as judged by

its specifications would be described thus:

With the electric-assist function, the vehicle can

be made to move forward with just light pressure on

the pedals. The vehicle can be stopped with

handbrakes or by simply removing one’s feet from

the pedals. Reversing is also possible. The vehicle is

pre-set so that it cannot go forward at a speed greater

than 6 km/h or reverse any faster than 0.5 km/h.

However, the users who are the subjects of this

study are all certified as requiring some level of

nursing care in their ADLs, as shown in Table 2, and

the functionality of the LW in the case of a facility

user greatly depends on the physical and mental

condition of the rider. Therefore, the question needs

to be revised to, “What kind of rider can move this

vehicle?” It must also be pointed out that since the

LW is not yet available on the commercial market,

facility users have no analogy with their past

experiences to refer to.

In FGIs carried out prior to the test riding of the

LW, we asked the health care professionals routinely

caring for the facility users what kind of person they

felt was suitable for this vehicle. During the loan

period of LW vehicles, we asked for volunteers

among the care professionals who would be willing

to encourage facility users to ride the LW. We then

asked them to predict whether each rider would

continue to ride the LW or not. Later, we included

these predictions in the personal portfolio.

3.2.2 Usability

Usability, according to ISO is defined as “the extent

to which a product can be used by specified users to

achieve specified goals with effectiveness,

efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of

use.” In this study, we created a histogram and

accumulated data chart comparing the riding rates of

continuous riders and those who discontinued riding,

a histogram of riding rates (number of rides / days at

facility) by attributes (sex, age cohort, care level) to

clarify what kind of people rode the LW at what

frequency. The effectiveness of the rides should also

be measured in terms of physical and mental effects,

but that is not within the scope of this study.

3.2.3 Experience

According to McNamara and Kirakowski (2005,

2006), judging experience requires answering the

question, “How do I relate to this product?” The

facility users who tried out the LW required

assistance in their ADLs, but they nevertheless made

the decision to ride the LW, tried it out several times,

and then decided to either continue or discontinue

riding during the period in which the vehicle was on

KnowledgeCreationinTechnologyEvaluationof4-WheelElectricPowerAssistedBicycleforFrailElderlyPersons-A

CaseStudyofaSalutogenicDeviceinHealthcareFacilitiesinJapan

91

loan to the facility. By keeping a record of their

reasons (for deciding to continue or discontinue use),

it was possible to learn what they found appealing,

or conversely, what they found to be a problem,

about the LW. Likewise, it was possible to find out

how they were influenced to try out the experience

of riding the LW. This data was collected by the

authors from the riding survey tables and through

interviews carried out after the vehicle loan period.

This study was carried out only after it had been

reviewed and approved by the ****************

research ethics committee. (authorization NBR:

2012021)

4 RESULTS

4.1 Circumstances which Elucidate

Knowledge Creation

In this experiment, not one facility user at the

daycare center attempted to ride the LW. At the

rehabilitation hospital, there were 61 users who rode

the vehicle. This result indicates that, without

exception, there was no knowledge creation

generated by the loan of the new AT device to the

daycare center. The following is an excerpt from an

interview related to this.

(D: Daycare Center Director; 1st: First Author;

2nd: Second Author; Ci: City Hall staff; En: LW

Engineer)

PT: When the vehicle was demonstrated, there

were two people who expressed interest, but they

never tried to ride the vehicle themselves.

D: They were told it was OK to ride the vehicle,

but the one person who we thought might be a

good candidate to try it out became sick and that

made a trial difficult.

1st: Yes, it may be difficult without an

atmosphere that this might become popular

within the facility.

PT: There was no word-of-mouth encouragement.

1st: If at least one person had tried it out, and

said it was fun....

PT: Yes, if that sort of thing had happened we

might have seen different results. But it didn’t

turn out that way, I’m sorry.

D: Persons who are undergoing rehabilitation are

working hard to resume their normal life, so for

someone like that a vehicle that they can pedal

on their own is appealing. There is a difference

between simply wanting to maintain your current

lifestyle such that, for example, even if you can’t

drive a car yourself, you can use a wheelchair or

your family will drive you, or you can have

groceries delivered, and being motivated to go

Figure 1: Flow of Data and Analyses.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

92

out on your own to do something. There is a

difference of drive and energy between the

two. ...

2nd: Apparently, people were reluctant to try out

the vehicle because they were told they could not

ride it outside. But even though they were

allowed to use it within the facility, no one tried,

so we were not able to find out how they might

have used the vehicle.

D: Given the size of the vehicle, it is not

surprising that people were reluctant to ride it

inside the facility. It is hard to imagine riding on

the LW through the same hallways in which

people are in wheelchairs, or walking, or even

just standing because they can’t walk. It doesn’t

seem reasonable to expect people to ride

smoothly inside a hospital.

Ci: I think it would be embarrassing, too. You

would have to have courage.

1st: You would stand out and you would feel

constrained to have to sweep by the other people.

D: A wheelchair would feel more natural. Two-

wheelers and 3-wheelers are what feel out of

place.

Ci: But if you get used to it, it wouldn’t be so

bad.

En: In America, people ride mobility scooters

[called “senior cars” in Japan] inside hospitals.

Ci: [It would be nice] if everyone could get used

to it that way.

(2013 Jan 30, Post interview FGI: Sayanoie

Daycare Center)

The daycare center is a place where elderly

persons certified as requiring care can spend time

during the day. They do not come to the center with

a specific purpose in mind, such as those who go to

the rehabilitation hospital, and there are no specified

activities for each individual. Still, just like at the

rehabilitation hospital, the daycare center PTs and

OTs did demonstrate the vehicle, riding the LW

themselves and inviting the facility users to do the

same. No one took them up on the invitation,

however. This indicates how important it is to have

someone try out the vehicle first in order to

disseminate use of the new AT device. Also, as

indicated in the interview excerpt above, the

conditions for health care knowledge creation in this

particular case are that facility users are highly

motivated to go outside, are proactive in their

lifestyles, and are not embarrassed to use the vehicle

inside the facility.

4.2 Functionality

4.2.1 The Type of Frail, Elderly Person for

Whom the LW Is Best Suited

Table 3 shows the characteristics that emerged from

the prior interview that best describe the type of

elderly person who would be able to make use of the

LW. As was shown in Figure 1, we collected 46

comments from interviews with care professionals.

Comments that were basically the same were

combined into one.

Table 3: Target image of frail elderly persons who are best

suited to use the LW vehicle.

Occupation ID Target image

CM S Forward-looking person

CM

S Candidate for secondary preventive care

CM

S

Person requiring preventive care or support as opposed to a

regular daycare user

CM

S

Person who is being taken care of by a general support

center (preventive care)

CM

S Person who wants to undergo rehabilitation

CM

S Person who can walk using a cane

CM

S

Person who thinks they can still ride a bicycle or who uses a

bicycle like a cane, but who others do not believe is actually

capable of riding a bicycle

CM

S

A relatively healthy elderly person who still farms (such as

in mountain valley areas or in tea fields)

CM

S Person who has not yet ridden a mobility scooter

CM

T

Person with relatively strong legs who can pedal (including

those with dementia)

PT A

Person who is mobile near the home using a cane or walker

but who has difficulty going further afield

PT

SW

Person who uses machines or bicycles for physical training

and rehabilitation

PT

A

Person who thinks they will be able to go outside if they

have this kind of vehicle

CW M Anyone who shows interest; anyone who likes vehicles

SW N

Person who is still riding bicycles but is losing confidence

in their ability to do so

Facility

director

IN

Person who doesn’t want to depend totally on a mobility

scooter

While no quantitative analysis has been made,

the comments shown in Table 3 contrast the target

image held by PTs and care managers. The PTs

speak of the facility user’s behavior and

psychological factors while the care managers tend

to base their target image on external markers such

as the facility user’s level of care, AT device, and

even occupation. Nevertheless, as will be

demonstrated in the next section on usability, these

kinds of external markers are not effective measures

of a user’s suitability for riding the LW.

4.2.2 PT’s Predictions of Whether a User

Will Continue or Discontinue Riding

Table 4 shows the PT’s predictions and actual

results of facility users’ continuity of riding. The rate

of accuracy of the PT’s predictions was around 50%.

KnowledgeCreationinTechnologyEvaluationof4-WheelElectricPowerAssistedBicycleforFrailElderlyPersons-A

CaseStudyofaSalutogenicDeviceinHealthcareFacilitiesinJapan

93

In Table 4, the “Neither” category indicates those

who rode only sporadically and for whom the PT

had difficulty deciding which category (continue or

discontinue) they belonged to.

Table 5 indicates the reasons for the PT’s

predictions. The numbers above the double line are

the PT’s predictions and the numbers below, the

actual results. The figure under “Prompt” indicates

the number of users the PT believed would respond

to or not respond to prompting. The criteria

“Prompt”, “Proactive”, and “Initiative” proved to be

effective measures for deciding whether a user was

likely to continue using the LW or not, but it was

found that the other criteria, “Willingness”

(willingness to try anything new), “Interest” (interest

in the LW vehicle), “Medical/physical condition”

(today’s condition), were not very effective

measures for judging a person’s reaction to the LW

vehicle. The reasons were recorded in the personal

portfolios, with each reason categorized in the 8

categories shown in Table 5. The PT sometimes

gave several reasons for a prediction, so the total

number of reasons is not the same as the total

number of riders.

Table 4: Rate of accuracy of PT’s prediction.

Result

Prediction

Continued Discontinued Total

Continue 31.1% 19.7% 50.8%

Neither 9.8% 14.8% 24.6%

Discontinue 6.6% 18.0% 24.6%

Total 47.5% 52.5% 100.0%

Table 5: Reasons for prediction by category.

Category

Prompt

Willingness

Proactive

initiative

Interest

Fear

Bicycle

Medical /

Physical

condition

All 10 11 12 7 19 3 5 9

Continue 7 6 8 5 5 0 1 2

Neither 3 1 2 1 7 0 2 1

Discontinue 0 4 2 1 7 3 2 6

4.3 Usability

The breakdown of the users who tried out the LW

vehicle in the rehabilitation hospital is as follows:

Age: 65-74: 22; 75-above: 39. Men: 36; Women: 25.

Care level: Support Level 1– LTC Level 4.

The number of days that a user came to the

facility varied according to the individual’s care

level and medical condition. In order to determine

what kind of persons rode the LW vehicle and to

what extent, it was necessary to calculate the rate of

riding by dividing the number of rides by the

number of days at the facility. Figure 2 compares the

riding rates and accumulated riding rates of those

who continued to ride against those who

discontinued. Those who continued where persons

who may have taken several breaks, but who

nevertheless continued to ride the LW vehicle

throughout the period it was on loan to the

rehabilitation hospital. Those who discontinued were

persons who tried out the vehicle a few times but

then stopped riding. There were only 4 riders in the

“Neither” category so we traced their record of

riding and re-categorized them in “continued” or

“discontinued”.

Looking at Figure 2, you can see that most of

those who discontinued riding generally did so after

they had reached a riding rate of around 20% (4

times). This indicates that the users were able to

judge by their fourth ride whether or not the LW

vehicle suited them. Those who continued to ride are

distributed between 20% to 90%, and half exceeded

a riding rate of 50%, indicating that they rode the

LW vehicle at least half of the days that they came

to the hospital.

Figure 2: LW riding rate and accumulated riding rate by

continued / discontinued category.

Figure 3: Rates by sex.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

94

Figure 4: Rates by age cohort.

Figure 5: Rates by care level.

Figures 3 through 5 indicate that more men than

women, and those older than 75 as compared to

those age 65 to 75, were likely to continue riding. In

terms of care levels, the greatest number of

continuing riders spans LTC Levels 1, 2 and 3, while

most of those at the less demanding care levels of

Support Levels 1 and 2 did not attempt to ride the

vehicle.

4.4 Experience

The most common reasons cited by users in their

personal portfolios for riding the LW vehicle were:

because I was encouraged to do so by the PT,

because it looked like fun, because I want to build

up some muscle, because I saw or heard about

someone riding, and because I want to be able to

ride a bicycle. Those who continued riding gave as

their reasons for doing so: able to go outside, fun,

encouraged to do so, condition was good, etc. Those

who discontinued riding gave as their reasons: hard

to ride, tiring, too slow, condition was poor, etc. As

was noted earlier, almost all of the 61 riders at the

rehabilitation hospital rode the LW vehicle at least

four times, suggesting that the PT’s encouragement

was a major factor in securing so many riders.

Below are some of the comments made in an FGI of

the rehabilitation hospital PTs during the experiment.

What these comments tell us is that the

rehabilitation hospital assigned staff specifically to

help with the trial rides, repeatedly encouraged users

to try out the vehicle, made adjustments as necessary

to ensure a smoother ride, called out a beat to give

the rider a rhythm by which to pedal, and otherwise

made proactive efforts to act as an interface between

the rider and the LW vehicle.

Table 6: PTs’ comments in midterm interview.

Topics Comments

Trial rides Start by gathering everyone together,

saying “Would you like to ride it? Let’s try

it.” Have a person get on the vehicle, show

them how to operate it and walk by them

as they go a few rounds. On the first ride,

the rider goes a few turns and tries out all

the vehicle’s functions. Each individual is

asked if they want to give it a try, and a

staff person accompanies each person who

decides to try riding. Once one person is

done, the next person is brought forward.

Those who want to try a second ride are

contacted by the facility staff.

Those who ride two or three times tend to

continue riding.

A common characteristic of those who

continue riding is that they are self-

sufficient at home but have difficulty

going out on their own.

These were mostly persons at support

level 1 and nursing care level 2.

There were some care level 3 people who

tried out the vehicle, but they generally

needed assistance in controlling the

vehicle, and some had to have help to keep

their feet on the pedals.

Those who had disabilities of their hands

or feet had difficulty controlling the

vehicle.

Encouragement

from hospital staff

during the

trial ride

Progress is uneven during the trial rides,

but we tried to encourage the rider by

helping them with rhythm, for example,

calling out, “One, two, one, two” each

time they stopped pedalling. The usual

staff worked with the riders [so they had

people they were familiar with helping

them out]

After the rider got on the vehicle, the seat

was adjusted (height, etc.) to ensure a

comfortable ride. It was slightly different

from adjusting a bicycle seat, but the staff

kept communicating with the rider, asking

“How does it feel?” and so on, and making

minor changes as needed.

(2012 Dec 1, Midterm FGI interview, Kakegawa Kita

Hospital)

5 CONCLUSIONS

As a new AT device, we found that the LW vehicle

could be fun and highly satisfactory to frail elderly

users who had difficulty walking on their own or

going outside. But this was an experience that could

not have been achieved without the interaction

between the PTs and the users. The PTs provided

encouragement, helped in adjusting the vehicle

settings, made judgments as to who might be suited

to ride the vehicle, and otherwise created new

knowledge to guide frail elderly persons to using the

KnowledgeCreationinTechnologyEvaluationof4-WheelElectricPowerAssistedBicycleforFrailElderlyPersons-A

CaseStudyofaSalutogenicDeviceinHealthcareFacilitiesinJapan

95

vehicle. In order for this kind of knowledge creation

to take place, it is imperative that the organization

provide an environment suitable for the use of the

device, that the user be proactive, and that dedicated

staff be appropriately assigned to assist as necessary.

In the setting of the rehabilitation hospital where

PT supervision was available, it was found that the

LW vehicle was best suited to users at LTC Levels 1

to 3 who were over the age of 75. At the same time,

there was considerable discrepancy among

individuals as to whether they would continue or

discontinue use of the vehicle. It was also found that

it was difficult for PTs to predict who would or

would not continue riding, and in this regard there is

a need for new knowledge creation.

The primary focus of the salutogenic perspective

on health is the individual’s ability, right up to the

time of death, to adapt to his or her own condition as

necessary to stay in good health. Today, there are a

variety of devices that support this ability. The more

devices that are made available to frail elderly

persons, the easier it will be to realize the kind of

health that is the focus of this perspective.

Unfortunately, major manufacturers are reluctant to

develop new products for the over-75 market

because of the fear of accidents and the probability

of being sued as a result. Still, the market for devices

for the over-75 age cohort is certain to expand and

there is ample room for innovation based on new

knowledge creation. As this study has shown, having

a new device evaluated within the context of a care

facility serves as an impetus to transform the tacit

knowledge of professional caregivers to explicit

knowledge. This requires, however, close

collaboration among the device maker, researchers,

and caregivers. In the current study, the city hall

staff also played an important role as intermediaries

bringing together diverse professionals and the staff

of the care facilities.

There are three topics that this study must

undertake in the future.

(1) Accurate measurement of effectiveness which

is a critical index for judging usability. We

need to elucidate the psychological and

physical effects of continuous use of the LW

vehicle.

(2) We need to provide a method, such as a

rehabilitation menu, by which care managers,

who are not as knowledgeable as PTs about

nursing care, can judge who is best suited to

use the LW vehicle.

(3) We need to consider what kind of knowledge

creation is needed to enable users to ride the

LW vehicle outside of the facilities.

REFERENCES

Abidi, S. S. R., Cheah, Y. N., Curran, J., 2005. A

knowledge creation info-structure to acquire and

crystallize the tacit knowledge of health-care experts.

Information Technology in Biomedicine. IEEE

Transactions, 9(2), 193-204.

Antonovsky, A., 1996. The salutogenic model as a theory

to guide health promotion. Health Promotion

International, 11(1), 11-18.

Applegate, W. B., Miller, S. T., Graney, M. J., Elam, J. T.,

Burns, R., Akins, D. E., 1990. A randomized,

controlled trial of a geriatric assessment unit in a

community rehabilitation hospital. The New Journal of

Medicine, 1572-1578.

Das, B., Kozey, J. W., 1999. Structural anthropometric

measurements for wheelchair mobile adults. Applied

Ergonomics, 30(5), 385-390.

Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B.,

Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., Seeman, T., Tracy, R., Kop,

W. J., Burke, G., McBurnie, M. A. for the

Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research

Group, 2001. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a

phenotype. Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences,

56 A (3), M146-M156.

Fukutomi, E., Okumiya, K., Wada, T., Sakamoto, R.,

Ishimoto, Y., Kimura, Y., Kasahara, Y., Chen, W.,

Imai, H., Fujisawa, M., Otuka, K., Matsubayashi, K.,

2013. Importance of cognitive assessment as part of

the Kihon Checklist developed by the Japanese

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for prediction

of frailty at 2-year follow up. Geriatrics and

Gerontology International, 13(3), 654-662.

ISO 9241, 1998., Ergonomic Requirements for Office

Work with Visual Display Terminals: Part 11:

Guidance on Usability.

Kickbusch, I., 2003. The contribution of the world health

organization to a new health and health promotion.

American Journal of Public Health, 93, 383–388.

Maki, Y., Ura, C., Yamaguchi, T., Murai, T., Isahai, M.,

Kaiho, A., Yamagumi,T., Tanaka, S., Miyamae, F.,

Sugiyama, M., Awata, S., Takahashi, R., Yamaguchi,

H., 2012. Effects of intervention using a community-

based walking program for prevention of mental

decline: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the

American Geriatrics Society, 60(3), 505-510.

Mann, W. C., Ottenbacher, K. J., Fraas, L., Tomita, M.,

and Granger, C. V., 1999. Effectiveness of assistive

technology and environmental interventions in

maintaining independence and reducing home care

costs for the frail elderly: A randomized controlled

trial. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(3), 210-217.

McNamara, N., Kirakowski, J., 2005. Defining usability:

quality of use or quality of experience? In

International Professional Communication Conference

Proceedings, IEEE. 200-204

McNamara, N., Kirakowski, J., 2006. Functionality,

usability, and user experience: three areas of concern.

Interactions, 13(6), 26-28.

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

96

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2011. Act for

partial revision of the Long-Term Care Insurance Act,

Etc., in order to strengthen long-term care service

infrastructure; 2011. Available at: http://www.mhlw.

go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/

dl/en_tp01.pdf.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., 2003. The knowledge-creating

theory revisited: knowledge creation as a synthesizing

process. Knowledge Management Research and

Practice, 1(1), 2-10.

Paquet, V., Feathers, D., 2004. An anthropometric study

of manual and powered wheelchair users. International

Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 33(3), 191-204.

Pickles, J., Hide, E., Maher, L., 2008. Experience based

design: a practical method of working with patients to

redesign services. Clinical Governance: An

International Journal, 13(1), 51-58.

Rubenstein, L. Z., 2006. Falls in older people:

epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for

prevention. Age and Ageing, 35(S2), 37-41.

Saijo, M., Suzuki, T., Watanabe, M., Kawamoto, S., 2013.

An analysis of multi-disciplinary & inter-agency

collaboration process: case study of a Japanese

community care access center, KMIS 2013, 66, 470-

475.

Sanders, E. B. N., Stappers, P. J., 2008. Co-creation and

the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5-18.

Tomata, Y., Hozawa, A., Ohmori-Matsuda, K., Nagai, M.,

Sugawara, Y., Nitta, A., Kuriyama, S., Tsuji, I., 2011.

Validation of the Kihon Checklist for predicting the

risk of 1-year incident long-term care insurance

certification: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Nippon

Koshu Eisei Zasshi, 58(1), 3-13. (In Japanese)

World Health Organization, 2014. Ageing and Life Course,

Available at: http://www.who.int/ageing/en/.

KnowledgeCreationinTechnologyEvaluationof4-WheelElectricPowerAssistedBicycleforFrailElderlyPersons-A

CaseStudyofaSalutogenicDeviceinHealthcareFacilitiesinJapan

97