What If We Considered Awareness for Sustainable Knowledge

Management?

Towards a Model for Self Regulated Knowledge Management Systems Based on

Acceptance Models of Technologies and Awareness

Carine Edith Toure

1,2

, Christine Michel

1,2

and Jean-Charles Marty

3

1

Université de Lyon, CNRS, Lyon, France

2

INSA-Lyon, LIRIS, UMR5205, F-69621, Villeurbanne, France

3

Université de Savoie, LIRIS, UMR5205, Villeurbanne, France

Keywords: Knowledge Management Systems (KMS), Acceptance, Continuance, Awareness, Regulation, Collaborative

Systems.

Abstract: We propose, in this paper, a model of continuous use of corporate collaborative KMS. Companies do not

always have the guaranty that their KMS will be continuously used. This statement can constitute an

important obstacle for knowledge management processes. Our work is based on the analysis of classical

models for initial and continuous use of technologies. We also analyse the regulation concept and explain

how it is valuable to support a continuous use of KMS. We observed that awareness may be a regulation

means that allows taking this problem into account. Awareness is a concept, which has been profusely used

to improve user experience in collaborative environments. It is an important element for regulation of

activity. In our model, we assume that one can integrate awareness in information systems to positively

influence beliefs about them. The final objective of our work is to refine some concepts to fit the

particularities of collaborative KMS and to propose an awareness regulation process using the traces of the

users’ interactions with the systems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Using KMS to support knowledge management

(KM) initiatives in companies is, nowadays, one of

the most often used approaches for KM (Boughzala

& Ermine, 2007). Companies increasingly invest in

collaborative or cooperative information systems

that promote capitalization of knowledge and

interactions between actors using this knowledge

through the system (Ermine, 2008). A successful

corporate KM process will thus maintain continuous

interactions between users and the system. The core

functionalities of KMS being publication, discovery,

collaboration and learning (Maier, 2007),

collaborators must publish/share, seek for

information, collaborate via the KMS in order to

sustain the knowledge flow within the system.

Nevertheless, this is not always the case and

companies usually have to deal with problems of

acceptance and use of their KMS.

The acceptance of a system can occur only when the

initial acceptance has been considered. Initial

acceptance corresponds to the first effective use of

the system. The acceptance is then satisfied when

users realize continuous use of the system, this is

called continuance (Bhattacherjee, 2001). Thus, to

carry out a sustainable KM initiative, companies

have to ensure a continuous use of their KMS.

In this paper, we propose to address the general

issue of regulation while using corporate

collaborative KMS. By regulation, we mean the

sustained commitment of the users toward the KMS

that guarantees the effective and long-term sharing,

seeking, learning and collaboration within users of

the company via the system.

It has been proven that activity awareness has a

prominent role in improvement and regulation of

interactions between the users and the information

system (Antunes, Herskovic, Ochoa, & Pino, 2014)

(Carroll et al., 2011). Being in the context of

collaborative systems, we will propose a model, for

self-regulation and sustainable KMS, which takes

413

Edith Toure C., Michel C. and Marty J..

What If We Considered Awareness for Sustainable Knowledge Management? - Towards a Model for Self Regulated Knowledge Management Systems

Based on Acceptance Models of Technologies and Awareness.

DOI: 10.5220/0005158604130418

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2014), pages 413-418

ISBN: 978-989-758-050-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

into account the concept of awareness in the use

activity. Our paper is organized as follows: in

section 2, we first propose to present an overview of

models for initial acceptance and continuance, and

then we discuss them and finally propose our model

for self-regulation of systems. In the last section, we

conclude and provide possible directions for future

research.

2 BACKGROUND AND

PROPOSITION

Most of acceptance models that have been published

in literature derived from social psychology theories.

They propose to explain people behaviours. These

researches led to models that are designed according

to a pattern published in the book of (Fishbein &

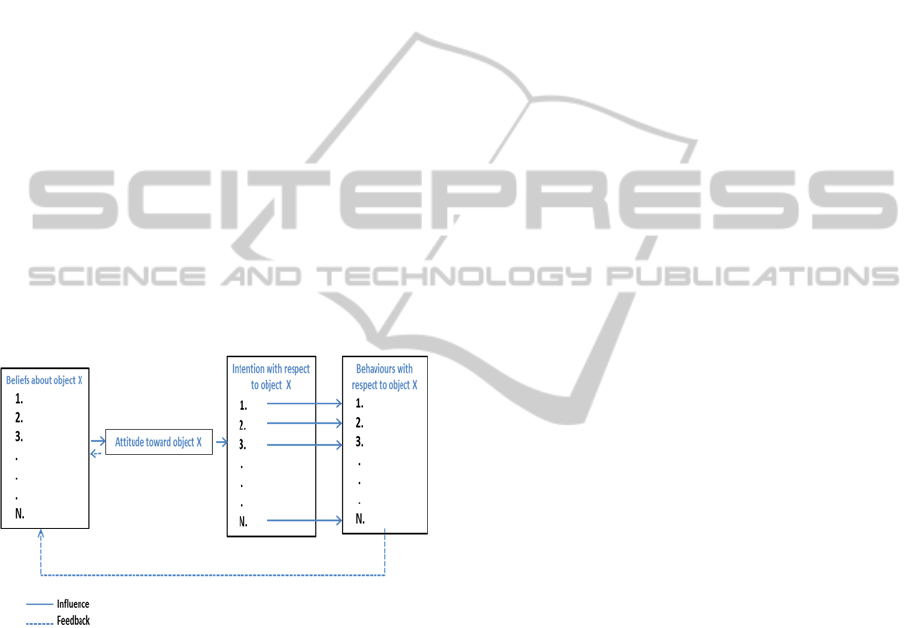

Ajzen, 1975). This pattern, as shown in the above

picture, contains causal links between the beliefs

about an object, the attitudes toward it, and the

intentions and behaviours associated to it. In the

following, we present some of the core models of

acceptance.

Figure 1: View of the pattern showing causal relationships

between beliefs, attitude, intention and behaviours.

2.1 Initial Use of Systems

In order to predict the effective use of information

systems in corporate environments, (Davis, 1993)

proposed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM).

In the TAM model, the beliefs of perceived

usefulness and perceived ease of use of a system are

the two fundamental criteria to build a positive

attitude toward technology and to stimulate the user

to start first experiments. More recently, (Venkatesh

et al., 2003) published the Unified Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

model, a unified model of 8 reference models and

theories for acceptance. About a decade later,

(Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu, 2012) proposed the

UTAUT2 which is an updated and more complete

version of their previous model. In addition to

factors like performance expectancy or effort

expectancy, they add some moderators such as the

age, the gender and the experience of the users.

2.2 Continuous Use of Systems

The different models cited previously were very

useful to figure out the intention of use and the

effective behaviours of people regarding

technologies. To address continuance,

(Bhattacherjee, 2001) proposed the Expectation

Confirmation Model (ECM) that uses variables like

perceived usefulness, confirmation and satisfaction.

Confirmation can be defined as the extent to which

the user opinion before using the system meets the

perception after an effective use. This confirmation

belief, which is constructed from user experience,

influences variables of satisfaction, continued use

intention and effective continued use.

Likewise, the Information System Success Model

(ISSM) of (Delone, 2003) also takes the use of the

system as a factor for a successful acceptance

process. The ISSM model indeed considers that the

system quality, the information quality, and the

service quality are to be considered independently.

They condition differently the intention of use and

also the satisfaction and the net benefits, ensuring

continuance.

(Jennex & Olfman, 2004) have adapted the ISSM

model for KMS systems by considering knowledge

quality and have validated it use, for KMS use

evaluation.

2.3 Discussions

We can observe a good level of coherence between

models of initial acceptance and those of

continuance. Indeed, the process of acceptance

begins with first beliefs that can be generated by

external stimuli like system quality or information

quality (cf. TAM or UTAUT models). Those beliefs

impact the user’s attitude toward the system, the

intention of use and therefore the effective behaviour

of use. After, this initial cycle of use, the user

acquires an experience that helps him to construct a

new belief confirming or disconfirming the previous

ones. This confirmation/disconfirmation thus

impacts his/her attitude (satisfaction or

dissatisfaction) and intention of use in the future,

and so on.

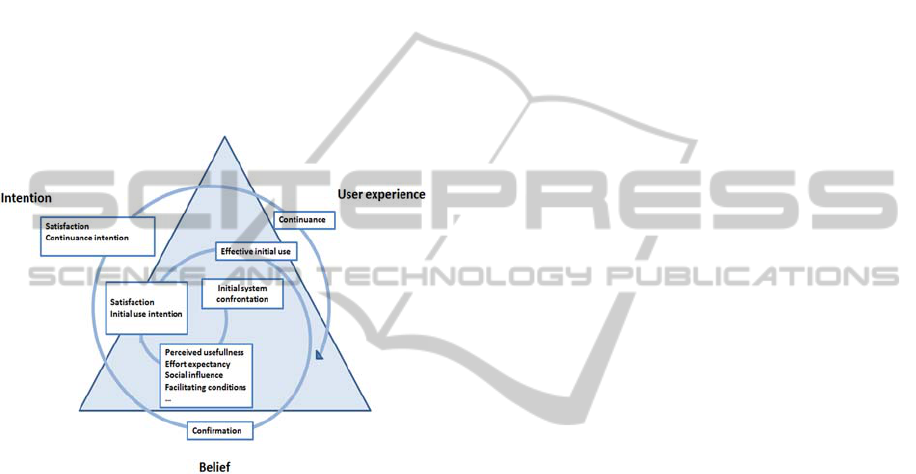

We can thus infer a spiral model (fig.2) of

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

414

sustainable use of systems based on the models

pattern of acceptance and continuance. The system

with its functionalities (information sharing,

discovering, publishing and learning) is in the centre

of the figure. When the user is first confronted with

the system, it is not necessarily through a use. It can

be through a presentation, a talk or an advertisement.

This first confrontation will influence emerging

beliefs (e.g. perceived usefulness, performance

expectancy, or effort), attitudes/intentions (e.g.

satisfaction, use intention) and behaviours (e.g.

initial use, continuance). Then s/he chooses to use it

or not, to build a new experience with it, to confirm

or not its beliefs, and so on as we explained before.

The continued use thus depends on the results of

each phase.

Figure 2: View of our synthetic model for sustainable use

of systems.

(Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) notice in their book that

attitudes and intentions are constructed at the same

time in someone brain. So, in order to simplify our

model, we merged the attitude and intention

variables under a unique label that is intention. We

also replaced the use behaviour by the user

experience to express that use have an impact on

user. This synthetic model will inspire us to propose

a model of sustainable use of KMS integrating

awareness concept. Our objective is to find a means

to reinforce positive beliefs and satisfaction in order

to sustain the continuance of use. We make the

hypotheses that awareness functions can be helpful

to do that.

2.4 Considering Awareness to Regulate

the Use of KMS

2.4.1 Awareness in Collaborative Systems

The concept of awareness has been used for many

years in the domain of computer supported

collaborative work (CSCW). (Harrison & Dourish,

1996) defines awareness as: “The sense of other

people’s presence and the ongoing awareness of

activity which allows us to structure our own

activity, seamlessly integrating communication and

collaboration ongoingly and unproblematically.” It

helps to support and facilitates interactions between

the users and the system (Antunes et al., 2014). It

also helps the user to construct the requisite

knowledge for performing his/her complex tasks

(Gutwin & Greenberg, 2002). Being aware of the

actual activities allows people to take autonomous

decisions for problem resolution. Awareness has

been profusely used to improve user experience in

collaborative environments. It allows the effective

regulation between actors participating in a shared

activity (Carroll et al., 2011). There are various

types of awareness (Antunes et al., 2014). Indeed

awareness can point out some specific elements

about the activity: collaboration awareness, location

awareness, context awareness, social awareness,

workspace awareness, situation awareness,

metacognitive awareness. Awareness can also

reflect the activities of a particular person or a group

of people: group awareness, individual awareness.

Awareness is used to support reflexive practices. In

his study of professional practises, (Schön, 1987)

showed that reflexive thought is a continuous

cognitive process, in which knowledge appears

through an iterative thinking process. A reflexive

process allows learners to be conscious of what they

have to do and how they do it, to analyse their

learning processes, to change and adapt their

behaviours in order to improve their way of learning.

The awareness of the action being performed then

becomes the source of knowledge and learning. The

group awareness has been defined by (Janssen,

Erkens, & Kirschner, 2011) as knowledge about the

social and collaborative environment the person is

working in (e.g., knowledge about the activities,

presence or participation of group members). The

authors argue that group awareness tools supply

information to users to facilitate coordination of

activities in the content space (space of collaboration

where users exchange information, discuss or solve

problems) or the social space (space for positive

group climate, effective and efficient collaboration).

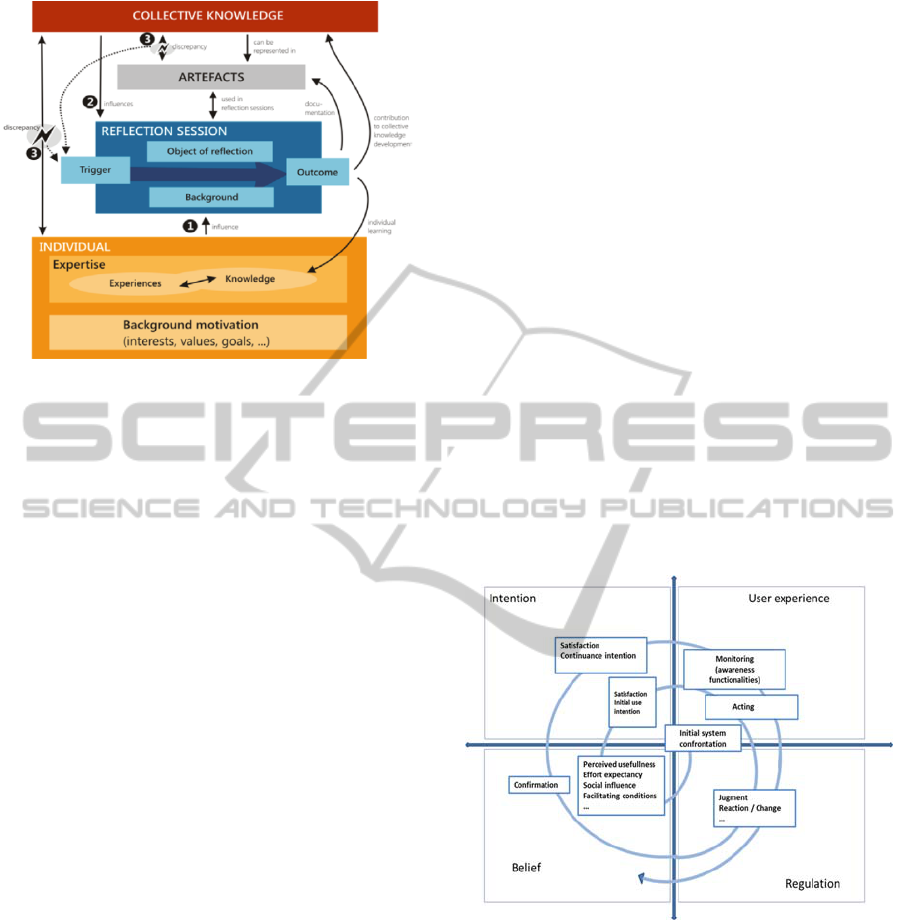

The model of (Krogstie, Schmidt, & Mora, 2013)

describes the links between reflection and

knowledge in professional contexts.

WhatIfWeConsideredAwarenessforSustainableKnowledgeManagement?-TowardsaModelforSelfRegulated

KnowledgeManagementSystemsBasedonAcceptanceModelsofTechnologiesandAwareness

415

Figure 3: A model connecting knowledge and reflection

(Krogstie et al., 2013).

Reflection sessions are supported by the

visualisation of indicators of the activities or the

state of mind. In some cases, the indicators are

presented directly near the activities they reflect.

NAVI surface (Charleer, Klerkx, Santos, & Duval,

2013) for example presents visualizations of user’s

communication activities by a “badge” presentation.

In other case, indicators are presented globally, into

a dashboard as it is the case in (Ji et al., 2013). The

reflection can be done by the user him/herself or

collaboratively, guided by an animator. In the

individual and group cases, the change process

occurring into this reflection session is called a

regulation process.

Regulation is defined as the “individual and social

processes of adaptation, engagement, participation,

learning, and development.” The authors also

introduce Self-regulation as “the cognitive and

metacognitive regulatory processes used by

individuals to plan, enact, and sustain their desired

courses of action”(Volet, Vauras, & Salonen, 2009).

Self-regulation is defined by (Zimmerman, 2000) as

a three steps process: self-monitoring, self-

judgement, and self-reaction.

2.4.2 Awareness for Knowledge

Management Systems

In collaborative KMS perspective, awareness can be

useful to encourage users to publish and share

information. They can also be informed of new

sharing and updates, and thus improve access to

recent content. This is an improvement for

discovery, publication and collaboration functions of

KMS systems. For example, in a collaborative

process of submission/publication of articles in a

corporate blogging platform, it is really useful for

both the contributor and the validator to have pieces

of information about the status of their activity. The

contributor will need to know whether or not his/her

new articles are actually processed by the validator,

who will need to have an overview of all the

submissions s/he has to validate (Gendron, 2010).

In addition, metacognitive awareness can improve

the learning process (Peña, Kayashima, Mizoguchi,

& Dominguez, 2013), which is another KMS core

functionality. Indeed, indicators of cognitive

awareness can for example present to the learner

his/her knowledge level or the improvement of

knowledge, the most difficult or easiest knowledge

and the number of solutions proposed by each

learner (Ji et al., 2013).

We thus assume that by proposing awareness

functionalities within the KMS, we could get a better

support of the regulation process and improve the

whole cycle of KMS use. Our model of continuous

use of systems who integrates awareness function is

presented in fig.4.

Figure 4: View of the model for sustainable use of KMS

systems with awareness functions.

This cycle for sustainable use of KMS begins, as our

synthetic model presented previously, with an initial

confrontation of the user with the system. This will

incent the emergence of different beliefs (perceived

usefulness, effort expectancy, etc.), and intentions.

To improve the user experience phase, we will add

some awareness functionalities in the system. When

the user will use the system, he will become aware

of collaboration and publication done by the others

or by him/herself. Moreover, awareness functions on

KMS can improve the discovery and learning

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

416

processes. These interactions with the system will

promote judgments, reaction and changes in the

behaviours of the user. The user will adapt

him/herself according to the system. We assume that

this phenomenon of regulation can positively

influence beliefs of confirmation, then intentions

(e.g. satisfaction, continued use intention) and

behaviours (continued use).

According to ECM model, these beliefs evolution

can reinforce the user’s engagement and

participation. Awareness indicators also help the

user to improve his/her skills, because s/he learns

from a global view on available information. His/her

behaviour can thus change. As an example, the

(Jennex & Olfman, 2004) KMS success model

presents the perceived benefit belief that positively

influences the continued KMS use.

3 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this work, we investigated awareness as an

incentive in the process of continuous use of

systems. We first reviewed several models of

acceptance of technologies and information systems.

This preliminary work helped us to deduct a

synthetic model of acceptance that inspired us to

propose a model for sustainable use of collaborative

KMS. We integrated in this model the concept of

awareness to emphasize users’ beliefs and reinforce

continuous use of the system.

Nevertheless, our work has just begun and we can

identify a number of steps we still have to achieve.

First, this model is based on researches made for

information systems and CSCW. As we are

interested in continuous use of collaborative KMS,

we need to precise, according to characteristics of

KMS, what sub-elements of each square are relevant

for our context. This will lead us to analyse more

deeply, each variable of the different identified

models, and keep only those that are valuable.

Then, we will implement and then evaluate our

model. Indeed, we are working with the Société du

Canal de Provence (SCP), a hydraulics Services

Company located in the Provence Alpes Côte

d’Azur French region. This company has massively

invested in a KMS for about a couple of decade. But

the initiative didn’t prove a great success because of

a lack of use. We want to add several awareness

functionalities in their KMS, and thanks to activity

indicators calculated with activity traces (Karray,

Chebel-Morello, & Zerhouni, 2014), we will

hopefully observe and measure the usage of the

system.

Finally, we also aim, based on this model, at

designing a cyclic methodology for implementation

of collaborative KMS that are self-regulated thanks

to awareness functionalities within the system.

REFERENCES

Antunes, P., Herskovic, V., Ochoa, S. F., & Pino, J. a.

(2014). Reviewing the quality of awareness support in

collaborative applications. Journal of Systems and

Software, 89, 146–169. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2013.11.1078

Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information

systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation

model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370.

Boughzala, I., & Ermine, J. L. (2007). La gestion des

connaissances, un nouveau modèle pour les

entreprises. In Management des connaissances en

entreprise - 2ème édition (pp. 47–86).

Carroll, J. M., Fellow, I., Jiang, H., Rosson, M. B., Shih,

S., Wang, J., … Pennsylvania, U. S. A. (2011).

Supporting Activity Awareness in Computer-Mediated

Collaboration, 1–12.

Charleer, S., Klerkx, J., Santos, J. L., & Duval, E. (2013).

Improving awareness and reflection through

collaborative , interactive visualizations of badges, 69–

81.

Davis, F. D. (1993). User acceptance of information

technology : system characteristics, user perceptions

and behavioral impacts.

Delone, W. H. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of

information systems success: a ten-year update.

Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4),

9–30.

Ermine, J. L. (2008). Management et ingénierie des

connaissances - Modèles et méthodes.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention

and Behavior : An introduction to Theory and

Research.

Gendron, E. (2010). Cadre conceptuel pour l’élaboration

d’indicateurs de collaboration à partir des traces

d’activité. Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1.

Gutwin, C., & Greenberg, S. (2002). A Descriptive

Framework of Workspace Awareness for Real-Time

Groupware. Computer Supported Cooperative Work

(CSCW), 11(3-4), 411–446. doi:10.1023/

A:1021271517844

Harrison, S., & Dourish, P. (1996). Re-place-ing space. In

Proceedings of the 1996 ACM conference on

Computer supported cooperative work - CSCW ’96

(pp. 67–76). New York, New York, USA: ACM Press.

doi:10.1145/240080.240193

Janssen, J., Erkens, G., & Kirschner, P. A. (2011). Group

awareness tools: It’s what you do with it that matters.

WhatIfWeConsideredAwarenessforSustainableKnowledgeManagement?-TowardsaModelforSelfRegulated

KnowledgeManagementSystemsBasedonAcceptanceModelsofTechnologiesandAwareness

417

Computers in Human Behavior, 27(3), 1046–1058.

doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.002

Jennex, M. E., & Olfman, L. (2004). Assessing

Knowledge Management Success / Effectiveness

Models, 00(C), 1–10.

Ji, M., Michel, C., Lavoué, E., George, S., Lyon, U. De,

Jean, U., & Lyon, M. (2013). An Architecture to

Combine Activity Traces and Reporting Traces to

Support Self-Regulation Processes.

Karray, M.-H., Chebel-Morello, B., & Zerhouni, N.

(2014). PETRA: Process Evolution using a TRAce-

based system on a maintenance platform. Knowledge-

Based Systems. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2014.03.010

Krogstie, B. R., Schmidt, A. P., & Mora, S. (2013).

Linking Reflective Learning and Knowledge Maturing

in Organizations. Third International Workshop on

Awareness and Reflection in Technology-Enhanced

Learning, 13–28.

Maier, R. (2007). Systems. In Knowledge management

systems - Information and communication

technologies for Knowledge Management (pp. 273 –

394).

Peña, A., Kayashima, M., Mizoguchi, R., & Dominguez,

R. (2013). A Conceptual Model of Metacognition to

Shape Knowledge and Regulation, 4–7.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner :

Towards a new design for teaching and learning in the

professions, 50(2).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Hall, M., Davis, G. B.,

Davis, F. D., & Walton, S. M. (2003). User acceptance

of information technology : Toward a unified view,

27(3), 425–478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012).

Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information

Technology : Extending the Unified Theory of

Acceptance and Use of Technology, 36(1), 157–178.

Volet, S., Vauras, M., & Salonen, P. (2009). Self- and

Social Regulation in Learning Contexts : An

Integrative Perspective Self- and Social Regulation in

Learning Contexts : An Integrative Perspective,

(September 2011), 37–41. doi:10.1080/

00461520903213584

Zimmerman, B. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social

cognitive perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation

(pp. 13–39).

KMIS2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

418