An e-Government Project Case Study

Interview based DEMO Axioms' Benefits Validation

Duarte Pinto

1

and David Aveiro

1,2,3

1

Exact Sciences and Engineering Centre, University of Madeira, Caminho da Penteada 9020-105 Funchal, Portugal

2

Madeira Interactive Technologies Institute, Caminho da Penteada, 9020-105 Funchal, Portugal

3

Center for Organizational Design and Engineering, INESC-INOV, Rua Alves Redol 9, 1000-029 Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Enterprise Engineering, Enterprise Change, DEMO, Case Study, Validation.

Abstract: This paper has as its background, a practical enterprise change project where the Design and Engineering

Methodology for Organizations (DEMO) was used in the initial stage as to give a neutral and concise but

comprehensive view of the organization of a local government administration in the process of

implementing an e-government project. The main contribution presented in this paper is an interview based

qualitative validation of some of DEMO's axioms and claimed benefits – something that, to our knowledge

has never been done up to now. Namely, we were able to validate DEMO's qualities of conciseness and

comprehensiveness brought about by the transaction and distinction axioms and also the stability of its

ontological models which are, by nature, highly abstracted from the human and technological means that

implement and operate an organization.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper has as its background a practical

enterprise change project where the Design and

Engineering Methodology for Organizations

(DEMO) was used in the initial stage with the

purpose to give a neutral and concise but

comprehensive view of the organization of a local

government administration having, itself, the

purpose to implement an e-government project. This

administration is present in a small island of a

European archipelago that is dependent on a main

island that has its own autonomous regional

government. We chose to apply DEMO in the

project, due to its growing use in projects in Europe

and purported qualities and benefits given by the

method. Such qualities highly fitted our work

context which had the need to harness the huge

complexity of the government administration target

of the project. The fact that, as far as we are aware

of, no academic study (qualitative or quantitative)

has ever been made to validate DEMO's qualities

gave rise to the idea of realizing research presented

in this paper. This small local government

administration – from now on referred to as SLGA –

is a kind of “miniature” replica of almost all

government functions from national to regional level

and – thanks to having so many functions

concentrated in a few persons – was chosen to be a

test pilot for the e-government project, later to be

extended to all government entities of the main

island. This project has three main aspects: (1) the

implementation of a work flow system to simplify

and automate many operational processes currently

paper based and/or – although using Word/Excel

documents – lacking in structure and coherence; (2)

the development of an online portal to automate as

much as possible the interactions and services

currently provided at a local physical Citizen Service

Desk (CSD), so that the citizens can initiate such

interactions in the comfort of their homes; and (3)

the development of an IT integration layer with

other regional and national government entities that

end up executing most of the processes. In this

context, our research team was assigned with the

responsibility of applying DEMO to model the

processes, interactions and information flows

occurring in the SLGA, to be used as a base for the

production of a strategic roadmap of organizational

changes that will have to occur for several

alternative scenarios of e-government

implementations, according to the possible levels of

integration and change in current government

entities and/or their IT systems. Our team comprised

4 DEMO experts, 2 working in the project full-time

138

Pinto D. and Aveiro D..

An e-Government Project Case Study - Interview based DEMO Axioms’ Benefits Validation.

DOI: 10.5220/0005171201380149

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD-2014), pages 138-149

ISBN: 978-989-758-049-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

and 2 part-time – one 50% and the other 25% –

totaling 55 man-days in a month of project

execution. Many interviews were made to officials

head of each of the SLGA's departments and also to

most of the officials responsible for each unit of

each department. Interviews were made both for

information collection and model validation. A final

global workshop with the presence of all

interviewees was made for final validation where

most models were deemed adequately correct and

complete after some small corrections and additions.

In the end we specified: 216 transactions – and their

associated result types; and 232 fact types – these

include classes/categories and fact types and exclude

properties. We additionally specified 250

ontological transaction kinds that followed a certain

repetitive pattern in certain departments and,

because of that, were abstracted into a small subset

of generic transactions of the above mentioned 216

transactions set. So, in fact, we specified almost 500

transaction kinds in this project.

Ten months after our main project activities

summarized above, we decided to conduct another

round of interviews having, as the main purpose, a

qualitative evaluation of DEMO's qualities of

conciseness and comprehensiveness brought about

by the transaction and distinction axioms and also

the stability of its ontological models. We took the

opportunity to re-validate all previously collected

data, and update existing models in case of

organizational changes. Very few changes and/or

corrections were needed demonstrating the stability

of the DEMO models which are, by nature, highly

abstracted from the human and technological means

implementing and operating an organization. The

qualities of conciseness and comprehensiveness

were also validated by the vast majority of the

interviewees. Regarding the interviews and their

analysis, we used a qualitative research method,

collecting the data with a previously conceived set

of questions specific for this case, most open ended

but with short answers. The outcomes in most

questions were mostly as expected but there were,

however, some peculiar answers.

In the remainder of this paper, section 2 presents

our Motivation, problem and research method. In

section 3, we present a brief introduction of DEMO -

Operation, Transaction and Distinction Axioms.

Section 4 has our Case details and Example

including some models of this case study. Section 5

explores the Interview questions and results based

on our experience and states the intentions behind

each question. Section 6 wraps it up with a Results

analysis and evaluation, and finally, in section 7, we

present our Conclusions.

2 MOTIVATION, PROBLEM AND

RESEARCH METHOD

Figure 1: Design Science Research Cycles.

We frame our motivation and research method in the

Design Science Research paradigm (Hevner et al.

2004)(Hevner 2007) which claims that all design

science research should take in account the three

cycles presented in Figure 1.

Regarding the relevance cycle, the motivation of

this study is the following problem: it is claimed in

(Dietz 2006) that DEMO possesses several qualities

but no formal proofs or studies are provided that

validate such claims. So our purpose was to validate

DEMO's qualities of conciseness,

comprehensiveness and stability of the ontological

models as to bring more weight and value in practice

to this method and associated theories. As for clear

definitions of these qualities, we adopt the ones from

(Dietz 2006). Namely by conciseness we mean that

no superfluous matters are contained in it, that the

whole is compact and succinct (Dietz 2006). That is,

models should provide a view containing the essence

that is a global picture of an organization out of

which all details can be properly specified.

Comprehensiveness implies that all relevant issues

are covered, that the whole is complete (Dietz 2006).

That is, all relevant perspectives like the dynamic

and static aspects of operation, human

responsibilities, operation flow and inter-

dependencies should be clearly understandable and

covered by the models. Stability of the ontological

models is supposedly guaranteed by the

implementation independence of DEMO models.

And by implementation it is understood the

assignment of human and/or computer resources to

operationalize an organization (Dietz 2006).

Looking at the rigor cycle we ground our study

on the sound formal theories behind DEMO and aim

to provide expertise to the Knowledge base while

contributing with a validation case study.

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

139

In respect to the design cycle, the research reported

in this paper aims to apply the DEMO artifact itself

and evaluate its claimed qualities by means of

interviews with key collaborators on the

organization target of study. Regarding such

evaluation, qualitative methods can facilitate the

study of issues in both depth and detail. They do not

have the constraints of predetermined categories of

analysis therefore allowing for a bigger depth,

openness and detail in the inquiry. On the other end

we find that quantitative methods require

standardized measures so that the varying

perspectives and experiences can fit in a limited

number of predetermined response categories to

which numbers are assigned (Patton & Patton 2002).

The main advantage of a quantitative approach is the

possibility to measure reactions of a large amount of

people to a limited set of questions, therefore

making comparisons and statistical aggregations of

data easier, and allowing for it to be presented in a

succinct way (Patton & Patton 2002). The

qualitative approach produces far more detailed

information about a much smaller sample of

individuals and cases. The qualitative approach

therefore increases the depth of the understanding of

the study but reduces the chances of it being

generalized (Patton & Patton 2002). The validity of

a quantitative research depends on careful

instrument construction that assures that what is

measured is really what is supposed to be measured.

This instrument must be appropriate and

standardized according to prescribed procedures.

The focus is on the measuring instrument, i.e. the

testing of the items, such as survey questions or

other measurement tools. In the qualitative inquiry,

the researchers are the instruments. The credibility

of these methods hinge in a great extent on the skill,

competence and rigor of the person doing the

fieldwork as well as what's going on in that person's

personal life that might prove to be a distraction

(Patton & Patton 2002). There is a third approach

that consists on mixing both of these methods, by

mixing both approaches, in some cases a researcher

can provide a better understanding of the problem

not using either the quantitative or qualitative

methods alone (Creswell & Plano Clark 2007). A

research using this third approach is usually named a

mixed methods research and can be defined as the

“class of research where the researcher mixes or

combines quantitative and qualitative research

techniques, methods, approaches, concepts or

language into a single study” (Johnson &

Onwuegbuzie 2004). By using a mixed methods

research, the researchers can provide more

comprehensive evidence than either quantitative or

qualitative research alone. Thus the researchers are

given permission to use all tools of data collection

available rather then being restricted to the types of

data collection associated with either of the methods

alone (Creswell & Plano Clark 2007). Given the

dimension of the SGLA target of our project and

analysis we have chosen a qualitative method

approach as we were limited to a small amount of

subjects having the knowledge about the modeled

processes.

As previously mentioned to achieve this

evaluation we opted to interview the key

collaborators involved, using a standardized open-

ended format that although lacking flexibility still

allowed us the use of open ended questions while

facilitating their analyzes furthermore the

generalization of the results (Patton & Patton 2002)

The interview method used can also be framed in the

seven stages of an interview investigation proposed

in (Kvale 1996).

1. Thematizing: formulation of a purpose of the

investigation and description of the topic being

investigated before starting the interviews – in this

case the purpose was the validation of the DEMO's

axioms in terms of the qualities of conciseness and

comprehensiveness and also the stability of its

ontological models. We wanted also to evaluate the

interview method itself. To achieve this we specified

several key points that the interviews should cover,

namely: (1) the duration of the interviews, (2) ability

by the collaborators to answer the questions in the

initial stage of the project both in the terms used by

the interviewers and their knowledge of what was

being asked for, (3) their opinion on the interview

methodology, (4) their current view on the processes

and eventual changes, (5) their perception of the

modeled workflow and ability to relate to the real

workflow in operation, (6) the names used in the

models, either in the organizational functions or the

transactions, (7) their self knowledge of the

organization, (8) the models and their

correspondence to current reality after almost a year

passed and (9) questions regarding the application of

the DEMO methodology and benefits obtained

thanks to its axioms.

2. Designing: planing the study taking in

consideration all the stages before the interviews

take place – to achieve this we devised a set of 43

questions that met the criteria set in the thematizing

as to approach all those 9 subjects, being most of

them open ended, but with the expectancy of rather

short answers considering the extent of the subjects

being inquired.

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

140

3. Interviewing: conducting the interviews based

on a guide and with a reflective approach

considering the desired knowledge – the round of

interviews was conducted with eleven SLGA

collaborators, ten that had been previously

interviewed, all either head of a department or chief

of a division, and one that, although not previously

interviewed, was now the current head of the human

resources department. Interviews took place

individually and were composed by the previously

mentioned set of 43 questions, placed after a re-

validation of the models that had been created for

the interviewee's department. Meetings were

previously scheduled and normally had a duration of

approximately one hour for all heads of department,

and two hours for the two chiefs of division so that

they could give their input on all the several

departments that they are responsible for.

4. Transcribing: preparing the interview results

for analysis; commonly translating oral speech into

written text – all answers were written down and

later organized into a spreadsheet containing all

participants together with the list of questions.

5. Analyzing: deciding, considering the purpose

of the interview and the interview material, what

methods are appropriate for analysis – in order to

facilitate analysis, our answer data was grouped in

sets according to common-theme questions. We then

studied the outcomes of each of those sets taking in

account the devised goals. All answers were also

analyzed individually for particularities and properly

considered in the presented results.

6. Verifying: ascertain the generalizability,

reliability, and validity of the interview findings i.e.

the possibility to apply the results in other contexts,

the consistency of the results, and if the study meets

the intended purpose – the findings of our research

are presented in chapter 6 Results analysis and

evaluation as also are the considerations relating to

those findings.

7. Reporting: communicate the findings and the

methods applied in a form that lives up to scientific

criteria, while taking the ethical aspects of the

investigation into consideration, and that having the

results in a readable and usable product for its

audience – in our case, to communicate our findings

we are using this paper, presenting the background,

contextualization and outcomes as well as a

description of the process used.

3 DEMO - OPERATION,

TRANSACTION AND

DISTINCTION AXIOMS

In the Ψ-theory (Dietz 2009) – on which DEMO is

based – the operation axiom (Dietz 2006) states that,

in organizations, subjects perform two kinds of acts:

production acts that have an effect in the production

world or P-world and coordination acts that have an

effect on the coordination world or C-world.

Subjects are actors performing an actor role

responsible for the execution of these acts. At any

moment, these worlds are in a particular state

specified by the C-facts and P-facts respectively

occurred until that moment in time. When active,

actors take the current state of the P-world and the

C-world into account. C-facts serve as agenda for

actors, which they constantly try to deal with. In

other words, actors interact by means of creating and

dealing with C-facts. This interaction between the

actors and the worlds is illustrated in Figure 3. It

depicts the operational principle of organizations

where actors are committed to deal adequately with

their agenda. The production acts contribute towards

the organization's objectives by bringing about or

delivering products and/or services to the

organization's environment and coordination acts are

the way actors enter into and comply with

commitments towards achieving a certain production

fact (Dietz 2008b).

Figure 2: Basic Transaction Pattern.

Figure 3: Actors Interaction with Production and

Coordination Worlds.

According to the Ψ-theory's transaction axiom the

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

141

coordination acts follow a certain path along a

generic universal pattern called transaction (Dietz

2006). The transaction pattern has three phases: (1)

the order phase, were the initiating actor role of the

transaction expresses his wishes in the shape of a

request, and the executing actor role promises to

produce the desired result; (2) the execution phase

where the executing actor role produces in fact the

desired result; and (3) the result phase, where the

executing actor role states the produced result and

the initiating actor role accepts that result, thus

effectively concluding the transaction. This

sequence is known as the basic transaction pattern,

illustrated in Figure 2, and only considers the “happy

case” where everything happens according to the

expected outcomes. All these five mandatory steps

must happen so that a new production fact is

realized. In (Dietz 2008b) we find the universal

transaction pattern that also considers many other

coordination acts, including cancellations and

rejections that may happen at every step of the

“happy path”.

Even though all transactions go through the four

– social commitment – coordination acts of request,

promise, state and accept, these may be performed

tacitly, i.e. without any kind of explicit

communication happening. This may happen due to

the traditional “no news is good news” rule or pure

forgetfulness which can lead to severe business

breakdown. Thus the importance of always

considering the full transaction pattern and the

initiator and executor roles when designing

organizations (Dietz 2008b).

The distinction axiom from the Ψ-theory states

that three human abilities play a significant role in

an organization's operation: (1) the forma ability that

concerns datalogical actions; (2) the informa that

concerns infological actions; and (3) the performa

that concerns ontological actions (Dietz 2006).

Regarding coordination acts, the performa ability

may be considered the essential human ability for

doing any kind of business as it concerns being able

to engage into commitments either as a performer or

as an addressee of a coordination act (Dietz 2008b).

When it comes to production, the performa ability

concerns the business actors. Those are the actors

who perform production acts like deciding or

judging or producing new and original (non

derivable) things, thus realizing the organization's

production facts. The informa ability on the other

hand concerns the intellectual actors, the ones who

perform infological acts like deriving or computing

already existing facts. And finally the forma ability

concerns the datalogical actors, the ones who

perform datalogical acts like gathering, distributing

or storing documents and or data. The organization

theorem states that actors in each of these abilities

form three kinds of systems whereas the D-

organization supports the I-organization with

datalogical services and the I-organization supports

the B-organization (from Business=Ontological)

with informational services (Dietz & Albani 2005).

By applying these axioms, DEMO is claimed to be

able to produce concise, coherent and complete

models with a reduction of around 90% in

complexity, compared to traditional approaches like

flowcharts and BPMN (Dietz 2008a).

4 CASE DETAILS AND

EXAMPLE

The SLGA currently has two divisions (had three at

the time of the first round of interviews in the

beginning of our project) which include ten main

departments. The first of those two is the Division of

Natural Resources Management (DNRM) that

includes the Veterinary, Fish, Parks and Agriculture

departments, all with a collaborator in charge, being

that the chief of the DNRM division is also in charge

of the Veterinary department. The second division is

the Division of Administration Finances,

Maintenance and Infrastructure Management

(DAFMIM) and comprises the departments of

Human Resources, Supply, Finance, Fleet,

Maintenance and the Citizen Service Desk, each also

with a different collaborator in charge. Each of these

departments deals with specific different aspects of

the SLGA. For example, the Veterinary department

has the only available veterinarian on the island and

deals mostly with farm animals health, safety and

well-being, and food safety issues regarding animal

based food and animal food itself. The Fish

department makes the bridge between the local

fisherman and the local commerce but also deals

with matters related with fishing boats diesel oil, the

selling of ice to local businesses and cold storage

units rental. On the DAFMIM division we find the

department of Human Resources that deals with the

allocation of the workers to the different

departments, their vacations, their evaluations, and

training programs in their unit as well as their day to

day task management realized by the head of each

department. The CSD, although included in the

DAFMIM is barely connected to the other

departments as it works as a local proxy for services

offered by multiple regional divisions located at the

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

142

Figure 4: CSD - Actor Transaction Diagram.

main island, such as employment related issues,

housing, driving related issues and so on. In Figure 4

we can see, an excerpt of the Actor Transaction

Diagram, produced for one of the SLGA

departments, the CSD, and the description can be

found in the following paragraphs.

In Figure 4 we can notice four clear clusters in

the ATD diagram, the first being the transactions

initiated by the citizen; it starts with a citizen service

that may or may not lead to a process realization –

e.g. the case that what the citizen needs is not

provided at this desk but in another specific

government office. If there is a process realization

then there will be a creation of process. The process

realization may have an associated cost

communicated in the process payment transaction.

But there are many processes with no costs

associated that may be target of an emission of proof

of receipt of the request for the realization of the

process. Hence why a step that usually would simply

be the state act of a payment transaction deserves to

be a transaction on its own. The second cluster is the

funds deposit cluster, this one is isolated from the

rest due to its nature. It is a daily transaction that can

only be done by one CSD coordinator at the end of

the day.

The third cluster is the process management

cluster, here are the transactions related with the

process done in the back-office when the CSD

collaborators are free from attending citizens. Two

of the datalogical transactions, the scanning of

documents of the process and archiving of these

documents of the process take place whenever the

CSD collaborators have free time, while the

forwarding process documents may vary depending

on the process forwarding method. If it's sent by fax

it takes place at the time of scanning. If it is sent by

paper through the ferry boat it takes place every

afternoon sometime before the ferry trip. The last

transaction in this cluster also takes place when the

CSD collaborators have free time, but it does not

happen every day as many of the CSD processes

have no returning documents, and in most that do,

those documents are sent directly to the citizen by

postal mail instead of returning to the CSD building.

Finally in the fourth cluster we have the process kind

management and its related transactions that, as we

previously stated, are meant to deal with the constant

change in processes and their related documents and

conditions.

The diagram described previously is a typical

example of contents presented to the interviewees

and already give an idea of the conciseness quality

of DEMO, something to which, as we will see just

next, almost all interviewees agreed to.

5 INTERVIEW QUESTIONS AND

RESULTS

The research pool for this interviews was rather

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

143

small with only eleven individuals but, considering

their positions within the organization and the

objectives of these interviews, this was a very

significant and useful sample. As previously

mentioned, the interview's questions were mostly

based on open ended questions, although most with

short sentence responses. When a simple yes or no

question was made, the usual follow up question

consisted in asking the reasons for such answer.

Out of 43 questions made in the interviews 20

are listed below in Table 1 with a summary of the

multiple outcomes. The other 23 questions were not

relevant for the focus of this paper, as they mostly

focused on: our interview method, approach and

language used in the first round of interviews in the

beginning of the project; as well as on comparisons

with results of two other modeling initiatives that

had occurred prior to ours. Unfortunately we were

unable to obtain enough information to compare our

approach with the others, as the key collaborators

involved in these other initiatives were no longer

working at the SGLA. Therefore, the other 23

questions are not present here, not only due to the

mentioned reasons but also due to space constraints.

The results obtained from these other questions will

be target of another paper. As many of the placed

questions were open ended, we have opted to

summarize and group the related answers in order to

present them in a more compact and intuitive

manner. For each question presented in the

following table, we present the number of

interviewees that answered with each of the

alternative or generally given responses, as well as

the total number of collaborators that in fact

answered to each specific question. After the table

we explain the goals and/or reasoning for each

question asked while already providing some

comments on the results. In the next section we do a

more thorough analysis on the outcome.

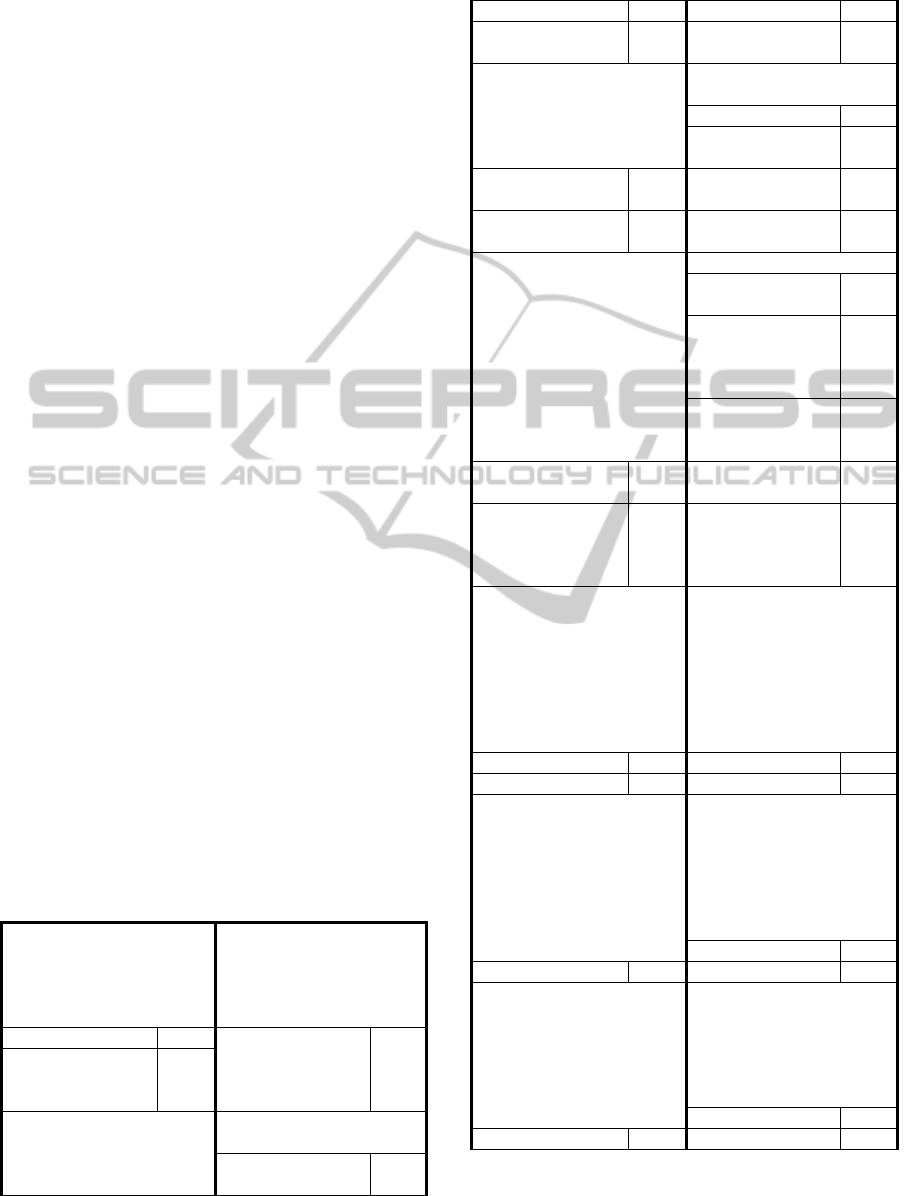

Table 1: Interview Answers.

7. Have you ever felt

difficulty with the framing

of the questions that were

made to you? (Regarding

the terms used)

14. How do you evaluate

the workflow in the models

when compared with the

real operational flow of

your work?

Had difficulty 1/10 Corresponds to the

real Work flow

11/11

Had no difficulty

(or quickly

answered)

9/10

15. Looking at the names

assigned to the transactions

would you change any?

16. Which one(s) would

you change?

Specification of

intervention

1/3

Table 1: Interview Answers. (cont.)

Yes 3/11 Expense process 1/3

No 8/11 Records for

statistical purposes

1/3

17. Looking at the names

assigned to the

organizational functions

would you change any?

18. Which one(s) would

you change?

DGMI responsible 1/3

Requester of

vehicle

2/3

Yes 3/11 Names of the

regional offices

1/3

No 8/11 Warehouse

responsible

1/3

19. Can you identify

anything produced in your

organizational area that you

cannot find described in the

models?

20. (If yes) 16. What?

HACCP Control

(fishery)

2/5

Management of

lighting and air.

(multi-purpose

pavilion)

1/5

Technical opinion

(supply and

finances)

1/5

Yes 5/11 Registration of

commitment

1/5

No 6/11 Decision of the

selection of

budgets (supply

and finances)

2/5

21. In your personal

opinion, do you feel that

these models can give you a

concise and unambiguous

notion of what goes on in

the organizational area

where you perform your

work?

28. Do you agree with all

transactions in the areas

under your responsibility?

Yes 11/11 Yes 11/11

No 0/11 No 0/11

29. (If no) Which are the

ones you do not agree with?

30. Can you find any of

your transactions, or one in

an area under your

responsibility that you had

a different perception of

the actors involved before

this modeling?

Yes 0/11

Answers 0/0 No 11/11

31. Which one (s)? 32. Do you consider that

the models that were

produced still describe the

reality of performed

transactions and involved

actors?

Yes 11/11

Answers 0/0 No 0/11

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

144

Table 1: Interview Answers. (cont.)

33. (If no) What has

changed?

35. Can you find any

reason for these models be

considered an important

resource in the knowledge

of the organization for their

own employees?

Yes 8/11

Answers 0/0 No 3/11

37. Suppose you had a new

employee under your

supervision and you had to

explain his roles within the

organization. Would you

consider using any of these

models as an aid in this

explanation?

38. Do you think these

models give you a

comprehensive and

summarized vision of the

organization's operation?

Yes 9/11 Yes 11/11

No 2/11 No 0/11

39. Why? 40. Do you believe that is

useful that these models

give a view abstracted of

implementation (regarding

people, technology,

technical, implementation

channels)?

All is discriminated

and summarized.

8/11

Reflects the steps

and processes and

who performs the

tasks.

1/11

Properly

diagrammed.

2/11 Yes 10/11

Generalized view. 1/11 No 1/11

41. Why? 42.Do you think that the

fact that these models

differentiate the initiator

and executor actor roles

and include the acts of

request, promise, execute,

accept and state a

transaction help understand

and clarify the

responsibilities of each

member of the

organization?

Because there is

constant change in

those items.

9/11

Because it is more

practical.

1/11 Yes 9/11

It makes it difficult

to give credit to the

proper person.

1/11 No 2/11

43. Why?

Because it clarifies

responsibilities

8/11

Needs to be well

explained so that

information does

not get lost

1/11

Can be used for

assigning blame

1/11

There is no need

because the process

is treated as a

whole

1/11

Question 7 tried to determine if the terms used

by us in the interviews were of difficult

understanding for the participants. By terms used,

we refer to more technical words such as actor, role,

and transaction, widely used in the DEMO

methodology. Nine of the participants stated that

either had no difficulty, or, if in fact some doubt

arose, it was promptly clarified by the interviewer's

explanation of the terms. One of the collaborators

however stated that she had in fact difficulty during

the questions as she had been “caught off guard”.

Question 14 had the intention to validate the

workflow modeled in the process step diagrams in

comparison to the real workflow in order to find any

flaws or changes in it. All the eleven collaborators

who answered this question agreed that the

workflow in the models was in fact similar to the

reality of their processes agreeing to what was

modeled in every step of each transaction.

Questions 15 and 16 were related to the names

specified for the transactions. Although there had

been already some discussion and validation on this

point around one year ago, we decided to re-evaluate

the appropriateness of these given names. Three of

collaborators found, each, just one name that they

would change in their department's models.

Questions 17 and 18 were on their turn related to

the names assigned to the organizational functions.

Three collaborators said they would change one or

more names. In fact it was somehow surprising that

one of the collaborators told us that some names

were not “generic” enough. As the positions within

the organization are in constant change the

DAFMIM chief of division did not agree that that

position was used as an organizational function, but

instead suggested that we used chief of said

department. In the same way, it was also suggested

to change the names of the regional authorities, as

they also suffer changes when another government is

elected. In this case it was suggested that we

changed to “regional direction with tutelage of said

service”. The other two suggestions by the other

collaborators were related to names that are more

commonly used, instead of the originally proposed

ones.

Questions 19 and 20 intended to identify possible

missing items that failed to be modeled originally.

Five of the collaborators were able to find items that

were not modeled. In the fish department the Hazard

analysis and critical control points (HACCP)

Control was not modeled initially as the head of the

department did not find it important at the time, but

as the paper print left in the process was significant

both him and the chief of the division in charge now

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

145

qualified it as significant. Finally on the supply and

finances department there were just three new

transactions proposed to be integrated in the current

steps of the product acquisition process. All-in-all,

the number of new items identified was quite small

compared to the vast amount of transactions that

kept stable during this whole year.

On question 21 we tried once again to receive

input by the members of the organization on how

DEMO was appropriate for the modeling, by asking

them if they found the models of their departments

concise and unambiguous. Every collaborator that

answered to this question confirmed this quality.

Questions 28 and 29 aimed at reinforcing the

comprehensiveness quality while confirming if all

collaborators agreed with all the listed transactions

in the models deeming them as needed or even as

essential.

With questions 30 and 31 we intended to find

any eventual discrepancy between the collaborators'

perception of reality compared to the modeled

transactions. No interviewed person had a different

perception of what was modeled, further reinforcing

the comprehensiveness quality.

Question 32 intended to capture the validity of

the work produced nearly one year before, and how

it was still applicable to the current reality. Even

though some collaborators and documents used

changed, all eleven interviewees agreed that all

models still correctly described the reality of the

organization.

Question 35 aimed to get a perception on the

relevance given to the DEMO models by the

collaborators. The answers here varied, and although

most collaborators said yes, three couldn’t find any

reason for the models to be relevant and another one

stated that their activities were already so mechanic

that the models were of little use.

Question 37 had the intention to obtain the

predisposition to use these models to explain

someone who was not familiarized with the

organization and their new tasks. Answers were

somehow similar to the previous question. Most

collaborators said yes, but one questioned the ability

of someone new to understand these models,

although another also mentioned that the actor

transaction diagram, would be a good model to

explain the procedures without complications. Still

another person that also said “no” mentioned also

that the models could be complicated, and it would

be more profitable time wise to show them the real

operations in practice.

With questions 38 and 39 we intended once more

to validate one of the claimed qualities of DEMO

models, and their perception by the organization's

members. To do so, we asked if the models gave a

comprehensive and summarized view of the

organization's operation. All interviewees answered

yes, and when asked why they thought like that,

there was little variation in their answers. Most

replies focused on how everything was

discriminated and properly summarized, others

stated that it was properly diagrammed and reflected

their department of the organization, one also

mentioned that it gave a generalized view of

everything, and finally it was also stated that it

clearly reflected step by step the processes of each

collaborator and their respective tasks.

The objective of question 40 was to validate the

level of abstraction used in DEMO and understand

to what extent this is assimilated by the collaborators

of an organization. Ten out of the eleven

interviewees answered that it was useful to use this

level of abstraction, while one said otherwise. When

asked why the responses showed the understanding

of the reasons as they were mostly based on the fact

that the organization is in constant change, new

employees join, old employees leave and the

documentation is also under constant updates,

therefore this level of abstraction allowed for the

models to remain correct after a long period of time,

and still reflect the reality of the organization, as

also demonstrated in the previous questions of the

interview. Although most answers were centered in

these aspects, one of the collaborators had a very

different opinion that may reflect some difficulty

understanding the method, as the reason used to

justify the “no” was that this level of abstraction

makes it difficult to give proper credit to a

collaborator when its due, because no person names

are used, but instead only the organizational

functions.

The last question of this interview focused on

determining if the collaborators found important the

fact that, in the models, there was a differentiation

between the initiator and executor roles as well as

the specification of each transaction's main steps of

request, promise, execute, state and accept. Nine of

the answers were positive, eight focused on how this

helped indeed to clarify the responsibilities, and how

important it is to know who is responsible for what

within each department. One answer had a different

justification: the organization needs to be well

explained so that information does not get lost, and

this way of modeling did exactly prevent that. There

were two collaborators on the “no” side, one stating

that there was no need for this differentiation in their

department because a single collaborator usually did

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

146

most of the transactions as being a single process,

and the other stated that clarifying the

responsibilities isn’t always good, as the goal of the

employees is to properly do their work, as such, they

normally don’t do mistakes on purpose. And, that

being the case, they should not look to assign blame

but instead work together as a group to fix what

went wrong.

6 RESULTS ANALYSIS AND

EVALUATION

With these interviews we were able to validate the

importance and relevance of the Ψ-theory's

operation, transaction and distinction axioms and the

qualities they bring about in the application of

DEMO. We will now see how these axioms affected

the modeling outcome and the perception the

interviewees have of their organization and of its

respective models, thus, validating the DEMO

qualities target of research in this paper.

In Table 2 we have a summary of our results

analysis where we present the three DEMO qualities

that we intended to validate in the research reported

in this paper, along with the questions (presented in

the first column) and the validating outcomes

(presented in the second column). The reasoning of

how the outcomes validate each quality can be found

after this table.

Table 2: Demo qualities analysis.

DEMO Quality - Concise

21. In your personal opinion, do you

feel that these models can give you a

concise and unambiguous notion of

what goes on in the organizational area

where you perform your work?

100% Yes

38, 39. Do you think these models give

you a comprehensive and summarized

vision of the organization Operation?

100% Yes

40, 41. Do you believe that is useful

that these models give a view abstracted

of implementation (regarding people,

technology, technical, implementation

channels)?

91% Yes

9% No

DEMO Quality - Comprehensive

7. Have you ever felt difficulty with the

framing of the questions that were made

to you? (Regarding the terms used)

10% Yes

90% No

14. How do you evaluate the workflow

in the models when compared with the

real operational flow of your work?

100%

Corresponds

fully

Table 2: Demo qualities analysis. (cont.)

19, 20. Can you identify anything

produced in your organizational area

that you cannot find described in the

models? (Note: in this question,

although almost half of the interviewees

found missing items, the percentage of

missing items in their area of

responsibility varied only from 1% to

6% and the other half reported 0% of

missing items)

45% Yes

55% No

28, 29. Do you agree with all

transactions in the areas under your

responsibility?

100% Yes

30, 31. Can you find any of your

transactions, or one in an area under

your responsibility that you had a

different perception of the actors

involved before this modeling?

100% No

35. Can you find any reason for these

models be considered an important

resource in the knowledge of the

organization for their own employees?

73% Yes

27% No

37. Suppose you had a new employee

under your supervision and you had to

explain his roles within the

organization. Would you consider using

any of these models as an aid in this

explanation?

82% Yes

18% No

38, 39. Do you think these models give

you a comprehensive and summarized

vision of the organization's operation?

100% Yes

42. Do you think that the fact that these

models differentiate the initiator and

executor actor roles and include the acts

of request, promise, execute, accept and

state of a transaction help understand

and clarify the responsibilities of each

member of the organization?

82% Yes

18% No

DEMO Quality - Stable

14. How do you evaluate the workflow

in the models when compared with the

real operational flow of your work?

100%

Corresponds

OK

15, 16. Looking at the names assigned

to the transactions would you change

any?

27% Yes

73% No

17, 18. Looking at the names assigned

to the organizational functions would

you change any?

27% Yes

73% No

32, 33. Do you consider that the models

that were produced still describe the

reality of performed transactions and

involved actors?

100% Yes

Question 7 was relevant to make sure that the

participants were at ease with the main concepts of

the DEMO approach – like actor and transaction –

leading to a correct comprehension of the models.

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

147

The strong positive result in this question supports

the comprehensiveness quality of DEMO.

Question 14 was a very important question in

order to demonstrate 2 points. By having a

unanimous answer on how the process step diagram

models reflected the proper workflow of the

organization's departments, we realize the great

importance of the transaction axiom. Thanks to the

structuring of the many essential and common

process steps in the transaction pattern, we managed

to uncover some “hidden” (in the minds of the

persons) transactions and, on the other hand, because

the collaborators become aware that a single

transaction “automatically” includes the many kinds

of social interactions that can happen regarding

some production, they end up evaluating the

modeled process fully corresponds to their daily

work. Thus, this outcome also validates DEMO's

comprehensiveness. We were also able to verify that

the models remained current even after multiple

changes in the organization in terms of persons and

documentation, demonstrating DEMO's quality of

model stability, brought about thanks to the

distinction axiom and its separation of the human

abilities, where we normally abstract from

information processing, communication and

document aspects.

Questions 15 to 18 allowed us to demonstrate

how the naming’s determined for both

organizational functions and transactions were quite

adequate for the collaborators that realize the

respective transactions, something that sometimes

proves difficult when gathering this kind of

information. There were three suggestions of

transaction name changes and four organizational

function changes, but taking in account the huge

number of almost 500 transactions that had been

modeled and the number of twice as much actor

roles involved (even though many repeat themselves

multiple times), the amount of change suggestions is

of very small significance. This outcome strongly

validates the stability of DEMO models.

Questions 19 and 20 demonstrated that, although

the DEMO approach seems to be a very good

approach compared to other methods, it is not

infallible and, as such, these questions allowed us to

detect some transactions that were not modeled on

the first round of interviews around one year ago.

But to give the due relevance to the amount of new

transactions found in a more precise fashion, we

now analyze the answers of each of the five

collaborators that answered this question

individually. One of the collaborators, the chief of

the division DAFMIM, identified three lacking

transactions while 317 transactions were modeled as

being under his responsibility, that is, not much

more than 1% of missing items. The other chief of

division (DNRM) identified only one missing

transaction in the set of 162 transactions modeled for

the areas under her responsibility. Again a

percentage close to 1%. The other three

collaborators – all department heads – identified as

missing transactions in their area of responsibility,

respectively: 1 out of 18, 1 out of 26 and 1 out of 31,

that is, percentages from 6% to 4%. The other 5

department heads could not find any missing item,

leading to 0% of missing items. These figures also

highly contribute to validate DEMO's quality of

comprehensiveness.

With question 21 we validated the conciseness

quality thanks to a unanimous response on how the

models really gave a concise and unambiguous

notion of each of the organizational areas to their

respective heads

Questions 28 and 29 demonstrated the

importance of the operation axiom on how it

allowed that interviewees' interactions within the

organization were correctly modeled, by having a

once again unanimous positive outcome when asked

if they agreed with all the transactions under their

areas of responsibility, thus also contributing to

comprehensiveness.

Questions 30 and 31 helped to demonstrate the

importance of the transaction axiom because all

modeled transactions had all the proper responsible

participants identified, thus also contributing the

comprehensiveness quality.

Questions 32 and 33 demonstrated the

importance of the distinction axiom by proving that

all models were still up to date thanks to the

separation of the ontological, infological and

datalogical aspects, thus reinforcing the validation of

the stability quality.

With questions 35 and 37 we tried to understand

if the models could be considered useful both for

existing collaborators and to help train new ones.

The outcomes were not always the expected but the

answers confirmed that the models were considered

important for the collaborators to have, not only

knowledge of their individual tasks, but also of other

tasks all over the organization. Although some

interviewees pointed out that some of the diagrams

could be difficult to understand and thus answered

negatively, the outcome is strong enough to also

contribute to validate the comprehensiveness

quality.

Finally, the block of questions from 38 to 43

allowed us to demonstrate the understanding by the

KEOD2014-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeEngineeringandOntologyDevelopment

148

organization's members of some key aspects of

DEMO such as the focus on abstraction from

implementation and the separation of the transaction

steps. Although not unanimously, the majority of

interviewed collaborators found these aspects

important and considered them a good quality of this

modeling process, as it can be seen from some of the

opinions we transcribed. So 38 and 39 clearly both

validate the qualities of comprehensiveness and also

conciseness. 40 and 41 distinctly validate the

conciseness quality, while 42 ends up also validating

comprehensiveness thanks to the clarification

provided by the clear identification of organizational

responsibilities.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Following the tenets of Design Science Research we

presented a relevant and needed contribution of an

interview based qualitative validation of some of

DEMO's axioms and claimed benefits – something

that, to our knowledge has never been done up to

now. Namely we looked at the qualities of

conciseness, comprehensiveness and stability of

DEMO's ontological models. This was done in the

context of a large scale practical DEMO project and,

to our knowledge, no publicly available study exists

that practically demonstrates such qualities. And

such studies like these – based in large scale projects

– are essential to contribute to a more widespread

and mainstream acceptance and adoption of DEMO

in enterprise change projects. We interviewed 11

key departments and division heads involved in a

large e-government project where around 500

ontological transactions were specified. Our research

was able to demonstrate that indeed DEMO's Ψ-

theory and its axioms contribute to provide a concise

and comprehensive view of the essential dynamic

and static aspects of an organization and that, even

after a year has passed, the majority of DEMO

models were still up to date and only needed to be

subjected to some minor changes. Our study has

limitations since the DEMO approach was evaluated

individually. In future studies we will apply also

other modeling approaches such as simple

flowcharts and/or BPMN based so that we can also

evaluate them in the same dimensions of analysis

target of this paper and we can compare the

performance of each approach according to the

perception of the organization's members.

Furthermore, the number of interviewees in the

research presented in this paper is not enough for a

pure quantitative validation which is something that

has to be done also to bring up even more solid

arguments supporting DEMO's claimed qualities.

We expect that, as the project advances from the

pilot stage in the small island to the full fledge stage

in the main island, then we will again apply DEMO

for modeling further processes to be implemented in

the e-government project and we will have a sample

of interviewees big enough for a pure quantitative

validation.

REFERENCES

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., Ram, S.: Design

science in information systems research. MIS

Quarterly. 28, 75–106 (2004).

Hevner, A.: A Three Cycle View of Design Science

Research. Scandinavian Journal of Information

Systems. 19, (2007).

Dietz, J. L. G.: Enterprise Ontology: Theory and

Methodology. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg (2006).

Patton, M.Q., Patton, M.Q.: Qualitative research and

evaluation methods. Sage, Thousand Oaks, Calif.

[etc.] (2002).

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L.: Designing and

conducting mixed methods research. SAGE

Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif. (2007).

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J.: Mixed Methods

Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has

Come. EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER. 33, 14–26

(2004).

Kvale, S.: InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative

Research Interviewing. SAGE Publications (1996).

Dietz, J. L. G.: Is it PHI TAO PSI or Bullshit? Presented at

the Methodologies for Enterprise Engineering

symposium , Delft (2009).

Dietz, J. L. G.: On the Nature of Business Rules.

Advances in Enterprise Engineering I. 1–15 (2008).

Dietz, J. L. G., Albani, A.: Basic notions regarding

business processes and supporting information

systems. Requirements Eng. 10, 175–183 (2005).

Dietz, J. L. G.: Architecture - Building strategy into

design. Academic Service - Sdu Uitgevers bv (2008).

Ane-GovernmentProjectCaseStudy-InterviewbasedDEMOAxioms'BenefitsValidation

149