Value-driven Design and Implementation of Business Processes

Transferring Strategy into Execution at Pace with Certainty

Mathias Kirchmer

1,2

1

BPM-D, 475 Timberline Trail, West Chester, PA 19382, U.S.A.

2

Organizational Dynamics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, U.S.A.

mathias.kirchmer@bpm-d.com

Keywords: ARIS, BPM, BPM-discipline, Execution, Innovation, Optimization, Modelling, Process Design, Process

Implementation, Reference Models, Strategy, Value-Driven BPM.

Abstract: An organization only competes with approximately 20% of its business processes. 80% of the processes are

commodity processes that can have an industry average performance. A value-driven process design and

implementation considers this by focusing innovation and optimization initiatives as well as individual

software development on the 20% high impact processes, while commodity processes are designed based on

industry reference models and implemented as far as possible through standard software. The paper

describes an approach to such a value-driven design and implementation of businesses – transferring

strategy into execution, at pace with certainty.

1 INTRODUCTION

A key challenge of organizations in today’s volatile

business environment is “leveraging people to build

a customer-centric performance-based culture”

(Mitchel, Ray, van Ark, 2014). Therefore it is not

only important to have a good strategy, hence to

know what to do. But in many organizations the key

challenge is about how to do things in order to build

such a customer and market-oriented organization.

This can be achieved through a consequent process-

orientation since processes deliver by definition a

result of value for a client outside the process.

However, this requires a structured value-driven

design of processes focusing on realizing the

business strategy of an organization (Rummler,

Ramias, Rummler, 2010) (Burlton, 2010).

This paper presents such a value-driven process

design and implementation approach that is both,

focused on executing the strategy of an organization

while being as resource efficient as possible. Result

is a practical and effective approach to process

design and implementation.

The approach has been developed based on

practical experience in large and mid-size

organizations, mainly in the USA and Europe. It has

been combined with academic research regarding

such value-driven design and implementation

methodologies.

2 TARGETING VALUE

The overall goal of the approach is to target and

focus on business value during the design and

implementation of processes. Research has shown

that organizations only compete with approximately

20% of their business processes (Franz, Kirchmer,

2012). This means that 80% of the business

processes are commodity processes which can be

carried out according to industry standards or

common industry practices. An average industry

performance is sufficient. Sophisticated

improvement approaches targeting higher

performance are not delivering real additional

busienss value. Hence, process innovation and

optimization initiatives have to focus on the 20%

high impact processes while other business

processes can be designed and implemented using

existing industry common practices. Results are

highly organization specific business processes

where this really delivers competitive advantages

and processes following industry common practices

where this is sufficient.

Such an approach also enables organizations to

use resources where they provide best value during

design and implementation initiatives. People who

are highly qualified in sophisticated process design

and implementation methods, for example, focus on

high value areas. They can systematically target

297

Kirchmer M.

Value-driven Design and Implementation of Business ProcessesTransferring Strategy into Execution at Pace with Certainty.

DOI: 10.5220/0005427402970302

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2014), pages 297-302

ISBN: 978-989-758-032-1

Copyright

c

2014 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

value as well as reduce the risk of project failure

(Kirchmer 2013). They can focus on moving the

organization to the next level. This reflects

requirements of a modern Chief Information Officer

(CIO) (Scheer 2013) who moves away from being a

technical expert to a driver of innovation and

performance. Hence, the approach allows such a

person to transition into a Chief Process Officer

(Franz, Kirchmer, 2012).

Such an approach requires the appropriate

segmentation of processes as basis for a

differentiated design and implementation approach.

Process models developed during the process design

need to reflect the requirements of those different

process segments and the importance of the resulting

business processes for the strategy of an

organization. Different levels of sophistication

regarding the improvement approaches are

necessary.

The following process implementation, including

the appropriate software support, is executed

accordingly to the process design based on the

identified process segments. The value-driven

design leads often to different approaches to procure

the enabling software. Highly organization-specific

processes often require an individual development of

software. Processes designed based on industry

standards lead in most cases to the use of standard

software packages.

Such a value-driven process design and

implementation approach enables the required

performance of an organization while meeting

efficiency goals. It helps creating a culture with the

right performance and customer focus by moving

strategy into execution at pace with certainty.

3 SEGMENTING PROCESSES

A business process assessment based on the impact

of a business process on main strategic value-drivers

is the basis for the segmentation of processes into

high impact and commodity processes (Franz,

Kirchmer, 2014). This process assessment is the key

tool to align business strategy with process design

and implementation. It enables the desired value-

driven approach and makes it a management

discipline to transfer business strategy into

execution.

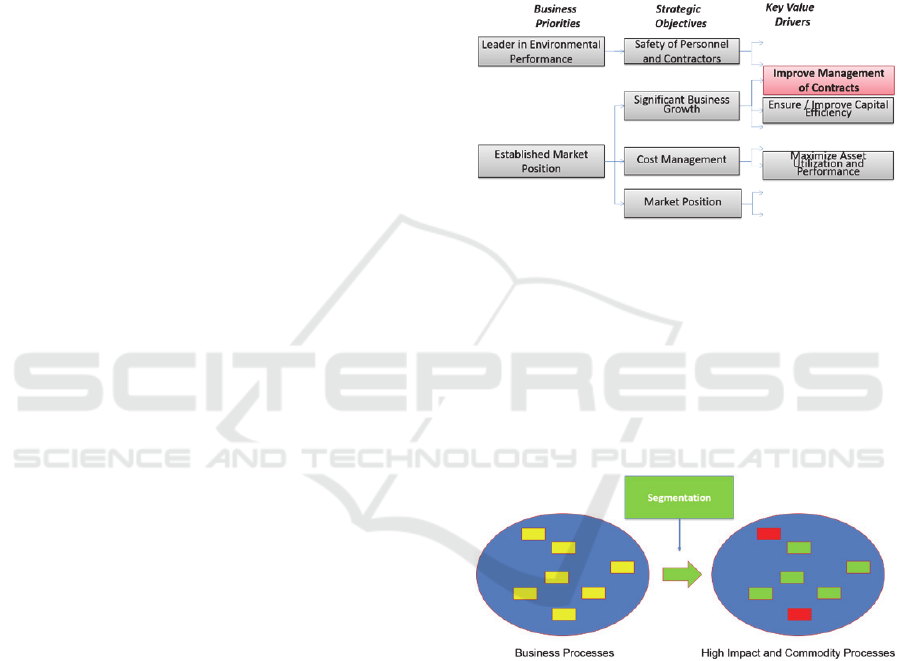

The value-drivers are deducted from the business

strategy of the organization using value-driver-tree

models (value-driver trees). This is a way of

transferring the strategic intension of an organization

into operational value-driven targets. An example

for such a value-driver tree is shown in figure 1. The

value-drivers themselves can again be prioritized to

focus the segmentation on the most important value-

drivers.

In practice a three step approach has proven to be

successful. The strategy delivers the business

priorities which are decomposed into strategic

objectives. Then one or several value-drivers are

identified for each objective, hence the drivers that

make this objective happen.

Figure 1: Value-driver tree (Excerpt).

The business processes of an organization are

then evaluated based on their total impact on the

specific value-drivers. Result are two segments of

business processes: high impact and commodity

processes. “High impact” processes are the ones that

are key to make the business strategy of the

organization happen. They link strategy to

execution. This approach is visualized in figure 2.

Figure 2: High impact and commodity processes.

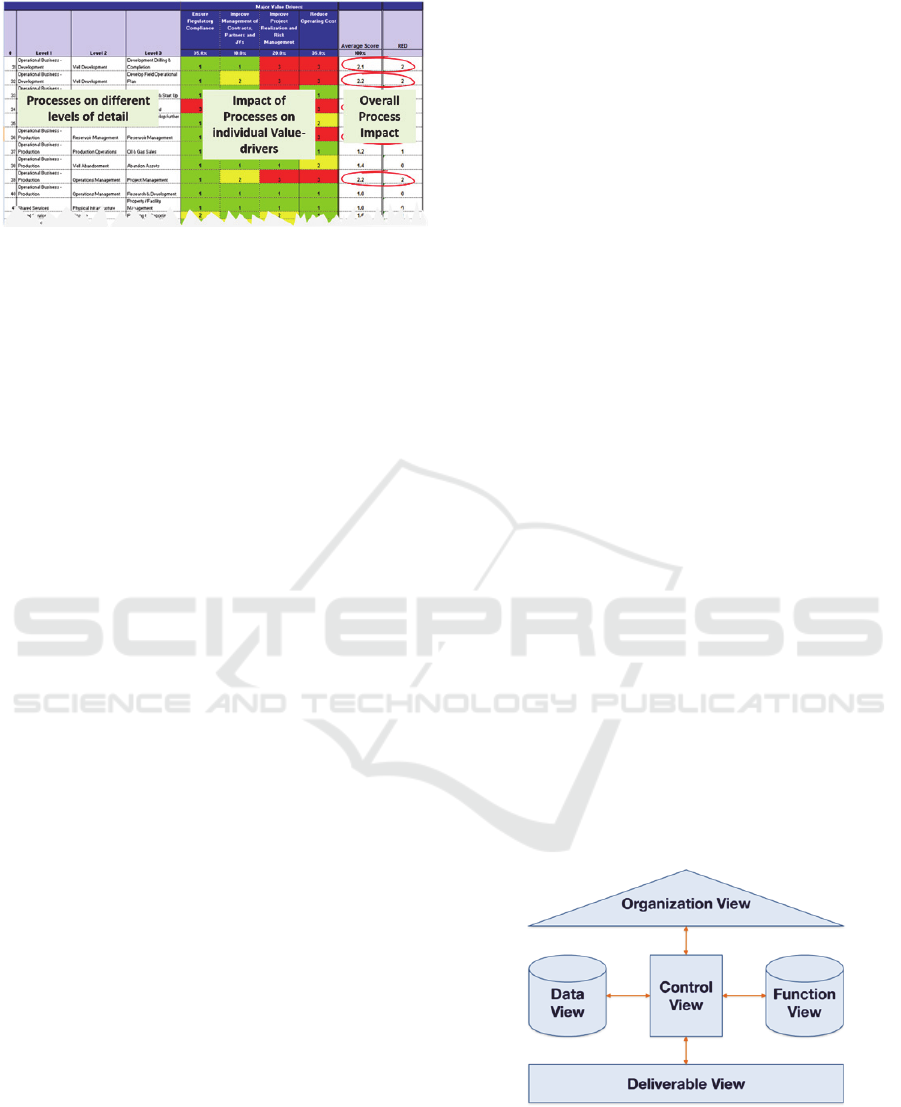

The value-drivers can be weighted regarding

their importance. Minor changes and adjustments in

strategy can then be just reflected through

adjustments of those weights. Larger strategy

changes result in different or additional value-

drivers. For each process it has to be defined if it has

no (0), low (1), medium (2) or high (3) impact on

each of the value-drivers. Then the overall impact is

calculated in a process assessment matrix by

multiplying impact with the weight of the

appropriate value-driver and calculating the total of

all impacts of a process. An example of a process

assessment matrix is shown in figure 3.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

298

Figure 3: Process assessment matrix (Excerpt).

The high impact processes have then to be

evaluated based on general industry practices, e.g.

through benchmarks or purely qualitative

evaluations. In that way you identify the high impact

“high opportunity” business processes. These are the

processes where improvements have the biggest

value potential since the process has a high impact

on the strategy but it currently performs only in or

even under the industry average.

Practice experience with different companies has

shown that the processes should be identified on a

level of detail so that 150-200 process definitions

describe the entire organization. This is often

referred to as “level 3” (L3). This level is detailed

enough to obtain differentiated results but high level

enough to avoid to high work efforts. Using the

results of the process assessment matrix the 20% of

the processes that are classified as high impact can

be identified. The others are the commodity

processes.

In practice there is often a “grey” area of

processes that could be in either group. Hence there

may be slightly more or less than 20% of the

processes in the high impact segment. This issue has

to be resolved in a case to case basis reflecting the

specific situation of an organization and its business

strategy.

4 VALUE-DRIVEN DESIGN

The high impact processes (or at least high impact

high opportunity processes, if further prioritization is

necessary, e.g. due to budgets) are subject to detailed

process innovation and optimization activities

focusing on the previously identified value-drivers

(Kirchmer, 2011). Therefore product and market-

oriented design approaches (Kirchmer, 1999b) have

been proven effective. The approach is used in

conjunction with the application of standard

modelling methods like Event-driven Process Chains

(EPC) or the Business Process Modelling Notation

(BPMN) to facilitate the integration of process

design and implementation. The product and market-

oriented design supports an integrated product

(offering) and process innovation. Such an approach

is especially important for the processes that are

highly relevant for the strategic positioning of an

organization. In order to identify these business

processes another segmentation of the high impact

processes is required distinguishing between

strategic and non-strategic high impact processes.

The focus is on high impact strategic processes

(Franz, Kirchmer, 2012). These are perfect targets

for innovation initiatives. As an example, a

compressor company may deliver “compressed air

as a service” instead of just selling compressors.

Offering and related sales processes change

simultaneously – reflected in the integrated design.

For all high impact processes techniques like

process model based simulations and animations are

helpful to come up with best suited design solutions.

Traditional improvement methods like Lean or Six

Sigma (George, 2010) can be applied in selected

cases. However, these are in general not approaches

that support a focused innovation. Hence, they are

more targeted to bringing less strategic people

intense processes to better efficiency, in most cases

resulting in cost or time reductions.

A structured modelling and design approach is

essential to produce models that enable a seamless

link to implementation. A perfect framework is

“ARIS”, the Architecture of Integrated Information

Systems (Scheer 1998). This facilitates the design of

processes from different view points: organization,

functions, data, deliverables and control flow. Result

are process models that contain all information for

the following implementation. The ARIS

architecture is shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: ARIS architecture by A.-W. Scheer.

Starting point for the design of commodity

processes are industry reference models. These

models are available for example through industry

organizations, consulting and software companies

Value-driven Design and Implementation of Business Processes - Transferring Strategy into Execution at Pace with

Certainty

299

(Kirchmer, 2011). In many cases they are already

developed using standard modelling methods. The

industry common practices reflected in those models

are only adjusted to the specific organization when

this is absolutely necessary. The process design

work focusses on “making the industry standard

happen”. If process areas are identified where the

industry standard cannot be applied, e.g. due to

product specifics, only those areas will be designed

in a company specific way, keeping the adjustments

as close to the industry standard as possible. Process

solutions can here often be found through a simple

application of the mentioned traditional

improvement methods like Lean and Six Sigma

since a pure efficiency focus is in most cases

justified here. However, it is important to keep in

mind that it is in general not worth improving above

industry standard performance.

This value-driven process design approach is

visualized in figure 5. It shows that also for the

design of high impact processes reference models

can be used as an input. But this is only one

component of getting all information together to

come up with real innovative and optimized

solutions.

Figure 5: Value-driven process design approach.

In both cases process models are developed until

the level of detail that still provides relevant

business information through the design. The

decomposition of the function “Enter Customer

Order” into “Enter First Name”, “Enter Last Name”,

etc. would from a business point of view not add any

additional relevant content (but may be necessary

later for the development of software). When

reference models are used this can mean that in areas

where the design deviates from the initial industry

model a higher level of modelling detail is required

then in other “standard” areas.

Both, high impact and commodity processes are

part of overlying end-to-end business processes.

Process-interfaces in the underlying detailed

processes reflect this overall context and make sure

that the various process components or sub-

processes fit together. Hence, during the process

improvement work cause-and-effect considerations

have to take place in order to avoid fixing issues in

one area while creating new ones in other processes.

5 VALUE-DRIVEN

IMPLEMENTATION

The very organization specific process models for

high impact business processes are in general

implemented using highly flexible next generation

process automation engines and require in most

cases the development of application software

components. The process models reflecting the

optimized and innovative design are the entrance

point for the more detailed modelling of the

underlying software. At this point the modelling

method can change, for example to the Unified

Modelling Language (UML), reflecting the desired

software structure to support the high impact

processes. Also the workflow engine of next

generation process automation engines can be

configured based on those models, depending on the

underlying modelling and execution technology

even automatically or semi-automatically. The

integration between process modelling and

execution tools can be extremely beneficial in this

situation.

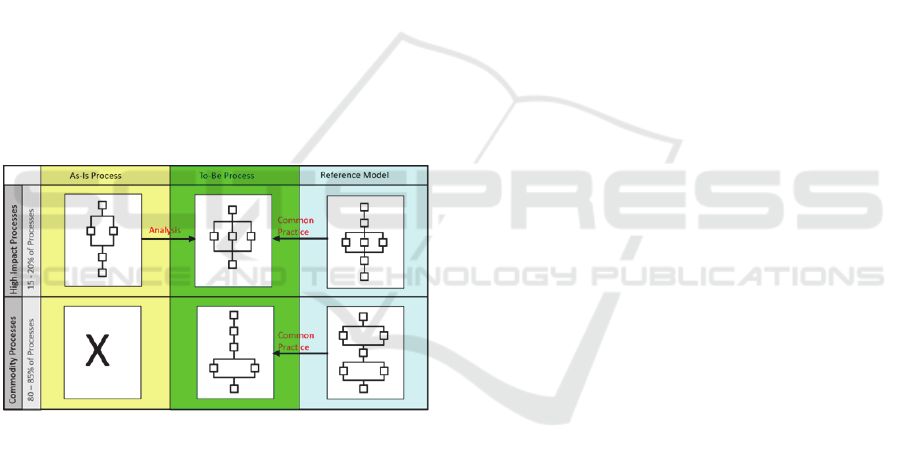

The overall architecture of such next generation

process automation environments is often referred to

as Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). In such an

architecture the “execution software” and the

“process logic” (workflow) are separated (Kirchmer,

2011) (Slama, Nelius, 2011). Hence, the developed

process models can on one hand be sued to

configure the workflow and on the other hand to

develop the software services that are not available

in existing libraries. Existing software services may

include detailed process reference models that can

be included in the process design. This architecture

of next generation process automation environments

is visualized in figure 6.

Key advantage of such an architecture is the high

degree of flexibility in adjusting process flows and

functionality. This can be crucial for a company

looking for agility and adaptability. Main

disadvantage is the effort for providing the

appropriate governance while running such an

environment as well as modelling efforts in the

building phase.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

300

Figure 6: Next generation process automation.

The process models of the commodity processes

are used to select or at least evaluate pre-selected

“traditional” software packages like Enterprise

Resource Planning (ERP) systems, Supply Chain

Management (SCM) or Customer Relationship

Management (CRM) systems. These can become

part of the overall next generation architecture,

representing one software component. Then those

models from the process design are used to drive a

process-oriented implementation of the software

packages across the various organizational units

involved in the business processes in scope

(Kirchmer, 1999). Ideally one uses already industry

specific software-reference models during the

process design. This means, one procures the

reference models to be used from the software

vendor. Hence, one benefits from the “business

content” of the software and minimizes design and

modelling efforts. Using other industry reference

models (different from the software based model)

may lead to design adjustments once the software is

selected.

Figure 7: Traditional software architecture.

Figure 7 shows the architecture of such a

traditional software. Here process definition and

software functionality are linked in a static way.

This means the software more or less dictates how a

process has to be executed (allowing only pre-

defined variants through the software configuration).

This is fine for commodity processes but causes

issues in strategic high impact processes that need to

be company specific. Consequently we have used

another implementation approach there. However, in

some cases it is also possible to develop add-on

software to support high impact processes and

integrate it into the larger software package, e.g. the

ERP system.

Advantages and disadvantages are just the

opposite as explained for next generation process

automation approaches. Hence, in practice a

combination of both efforts is in most cases the

solutions that delivers best value.

The process-interfaces in the different process

models guide the software integration. This can be

supported from a technology point of view through

appropriate enterprise application integration

environments – in general included in SOA

environments. Such software tools or middle-ware

tools reduce the efforts for interface development to

a necessary minimum. Their efficient use is again

driven through the appropriate process models,

specifically the integration of the various process

components.

Result are end-to-end business processes based

on a value-driven process design and an appropriate

integrated automation. The approaches provides the

necessary flexibility where it delivers real business

value and the required efficiency where possible.

Business process management, software selection

and development are integrated in one overlaying

discipline of value-driven business process

management (BPM) (Franz, Kirchmer, 2014)

(Franz, Kirchmer, 2012).

6 CONCLUSIONS

The approach of value-driven business process

design and implementation allows an organization to

move its strategy systematically into execution. It

aligns the modelling and implementation efforts

with the strategic direction of the organization.

First experiences with real live companies

showed that this approach helps on one hand to

dramatically reduce process design and

implementation times due to the efficient handling

of commodity processes. Companies estimated more

than 50% savings in time and effort. On the other

hand it enables real strategic advantage though the

innovation and optimisation of high impact process

areas.

While the basic approach has proven to be

successful in practice there are still gaps to close. In

Value-driven Design and Implementation of Business Processes - Transferring Strategy into Execution at Pace with

Certainty

301

the design part the systematic achievement of

appropriate process innovation is still a topic that

needs further research. Considering the importance

of process innovation, this is a real key topic. In the

field of process implementation the integration of

the process modelling and execution environments

can still be improved. While there is quite a bit of

progress on the software-side (Scheer 2013) (Stary

2012), there is still work to do on an integrating

software and organizational governance solution.

REFERENCES

Burlton, 2013. Delivering Business Strategy through

Process Management. In: Vom Brocke, J., Roemann,

M.: Handbook on Busienss Process Management 2 –

Strategic Aignment, Governance, People and Culture,

Springer, Berline, New York, e.a.

Elzina, Gulledge, Lee, 1999. Business Engineering,

Springer, Norwell.

Franz, Kirchmer, 2012. Value-driven business Process

Management – The Value-Switch for Lasting

Competitive Advantage, McGraw-Hill, New York, e.a.

Franz, Kirchmer, 2014. The BPM-Discipline – Enabling

the Next Generation Enterprise. BPM-D Executive

Training Documentation, London, Philadelphia.

George, 2010. The Lean Six Sigma Guide to Doing More

with Less – Cut Costs, Reduce Waste, and Lower your

Overhead. McGraw-Hill, New York, e.a.

Kirchmer, 2013. How to create successful IT Projects with

Value-driven BPM, In: CIO Magazine Online,

February 27th 2013.

Kirchmer, 2011. High Performance through Process

Excellence – From Strategy to Execution with

Business Process Management. Springer, 2nd edition,

Berlin, e.a.

Kirchmer, 1999a. Business Process Oriented

Implementation of Standard Software – How to

achieve Competitive Advantage Efficiently and

Effectively. Springer, 2nd edition, Berline, e.a.

Kirchmer, 1999b. Market- and Product-oriented Definition

of Business Processes. In: Elzina, D.J., Gulledge, T.R.,

Lee, C.-Y (editors): Business Engineering, Springer,

Norwell.

Mitchel, Ray., van Ark, 2014.: The Conference Board –

CEO Challenge 2014: People and Performance,

Reconnecting with the Customer and Reshaping the

Culture of Work. The Conference Board Whitepaer,

New York, e.a. 2014.

Rummler, Ramias, Rummler, 2010: White Space

Revisited – Vreating Value thorugh Processes.Wiley,

San Francisco.

Scheer, 2013. Tipps fuer den CIO: Vom Tekki zum

Treiber neuer Business Modelle. In: IM+IO – Das

Magazin fuer Innovation, Organisation und

Management, Sonderausgabe, Dezember 2013.

Scheer, 1998. ARIS – Business Process Frameworks,

Springer, 2nd edition, Berlin, e.g.

Slama, Nelius, 2011. Enterprise BPM – Erfolgsrezepte

fuer unternehmensweites Prozessmanagement.

dpunkt.verlag, Heidelberg.

Stary, 2012. S-BPM One – Scientific Research. 4th

International Conference, S-BPM ONE 2012, Vienna,

Austria, April 2012, Proceedings.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

302