Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity:

Theoretical Background and Design Process

Gilles Kermarrec

1

, Yannick Guillodo

2

, Damien Mutambayi

2

and Léo Ballarin

2

1

European Research Center for Virtual Reality and Research Center for Education,

Learning and Didactics, European University of Brittany, France

2

Coaching Sport Santé Company, 2920 Brest, France

Abstract. Considering advances from research and technologies concerning

physical activity and health, this chapter presents the C2S’s Project (Coaching

Sport Santé). C2S is a French start-up aiming at designing a device for promot-

ing Daily Physical Activity (DPA). Based on Self-Determination, Self-Esteem

Self-Regulation theories, and on the Trans-theoretical Model of Behaviour

Change, a mobile phone App was developed including pedometer technology.

The app offer a five step-strategy aimed at taking in account a) initial or normal

everyday steps counts, b) individual motivational factor, and c) personally-

adapted feedbacks.

1 Introduction

Benefits of physical activity for improving health are well established. Regular physi-

cal activity is associated with enhanced health and reduced risk of mortality factors,

including cardiovascular disease,

ischemic stroke, non–insulin-dependent, diabetes,

colon cancers,

osteoporosis, depression,

and fall-related injuries (for an review see

[1]).

Therefore, a survey of EU countries demonstrated that two thirds of the adult

population did not reach recommended levels of physical activity (http://

www.who.int/whr/2002/en). In contrary, the prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle has

been established in the European Space (e.g. in the 15 Member States of the European

Union, [2]). Sedentary lifestyle has been defined according to various criteria: the

number of hours that individuals spend sitting down in a typical day, the number of

hours expended walking or in other specific physical activities, or how many times a

week they participated in an activity that induced sweating [3]. Recently Europeans

have been identified as high-risk populations; thus, the European Union’s council

recommendation of 26 Nov 2013 on promoting health enhancing physical activity

called for monitoring of physical activity levels across member states. The Determi-

nants of Diet and Physical Activity (DEDIPAC) European knowledge hub

(www.dedipac.eu) organizes a major workshop on physical activity and sedentary

behaviour surveillance and assessment in may 2015.

Considering these advertising, and advances from research and technologies, this

chapter presents the C2S’s Project (Coaching Sport Santé). C2S is a French start-up

aiming at designing tools for promoting Daily Physical Activity (DPA). Especially, an

interdisciplinary team of exercise psychologist, doctor and health experts, managers

and engineers collaborated in designing a physical activity smartphone application.

Guillodo Y., Ballarin L., Mutambayi D. and Kermarrec G.

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process.

DOI: 10.5220/0006157001130124

In European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health and Sports (EPS Rome 2014), pages 113-124

ISBN: 978-989-758-154-0

Copyright

c

2014 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

113

Based on Self-Determination, Self-Esteem Self-Regulation theories, and on the Trans-

theoretical Model of Behaviour Change, a device including a mobile phone App was

developed to promote Daily Physical Activity (DPA).

The purpose of this chapter is to summarize reviews about physical activity inter-

ventions, to provide a framework for increasing DPA, and to present our App’s design

process and its outcomes.

2 Changing for Daily Physical Activity: Advances from Research

Recommendations in order to benefit from regular physical activity are well-known:

30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity on 5 or more days per week, or 20 minutes

of vigorous-intensity activity on 3 or more days per week. Activities that expend 3- to

6-fold the energy expenditure of sitting at rest (3 to 6 metabolic equivalents or METs,

1 MET=3.5 ml O2•kg-1•min-1) are defined as moderate (walking), those that expend

more as vigorous, and less as light intensity (running) [4]. Strategies and interventions

to promote DPA are problematic. Several reviews have been conducted in this area

and provided us with guidance for our project. The conclusions can be summarized

into three points.

2.1 Several Types of Interventions for the Promotion of Physical

Activity

Kahn et al., [5] produced a systematic review of interventions for the promotion of

physical activity. Three categories of interventions have been distinguished:

- Informational approaches to change knowledge and attitudes about the benefits;

especially in the self-regulation theory, knowledge about PA and health are a key

component of the behavioural change mechanism. Knowledge help people to

identify new goals and goals lead to behavioural strategies.

- Behavioural approaches to teach people the skills necessary for both successful

adoption and maintenance of behaviour change. Especially studies including goal

setting, self-monitoring, self-assessment, specific feedbacks showed that behav-

ioural change in DPA could be achieved.

- Environmental and policy approaches to change the structure of physical and

organizational environments to provide safe, attractive, and convenient places for

physical activity. Especially, interpersonal setting is often thought to have poten-

tial for motivation (cooperation and competition) and social support are effective

in increasing PA level.

Behavioural approaches and individually adapted health behaviour change programs

consist of the most successful way. There is strong evidence that this kind of face-to-

face PA programs are effective in increasing level of physical activity. Thus, face-to-

face interventions are considered to be the optimal means for changing health-related

behaviour.

114

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

114

2.2 Findings of Research on PA Interventions

Hillsdon et al., [6] summarized the evidence from sixteen systematic reviews and

meta-analyses. Their ‘review of reviews’ provided a summary of the findings of re-

search on interventions aiming at promoting physical activity for adults.

Evidences suggested that short-term change is achievable, and that use of a moti-

vational and behaviour change theory will help. For instance, intervention could be

based on various social cognitive theory of motivation (e. g., self-efficacy theory,

self-regulation theory) or on the trans-theoretical model of change. Nevertheless, in

many studies evidences were not consistent, or the research method could be criti-

cized because PA was assessed thanks to declarative and self-administered question-

naires, such as the “International Physical Activity Questionnaire”.

Moreover, the authors pointed out there are no consistent evidence for changes in

workplace settings despite the fact that the importance of promoting physical activity

through organisations is frequently pointed out. Especially the workplace, while tar-

geted extensively in North America, has shown inconsistent involvement in physical

activity promotion especially in European Space. Nevertheless, the workplace can

offer large numbers of individuals and larger companies use to offer an infrastructure

to support health promotion initiatives. Considering that adults spend about one quar-

ter of their time at their place of work during their working lives, walking may be the

best way to increase DPA, so that we suggested that pedometer technology could be

relevant for the C2S project.

2.3 Pedometers: Furnishing a Realistic Measure for DPA

Biddle and Mutrie [7] produced a synthesis of the literature in which the use of pe-

dometers is considered an efficient motivational tool. Using pedometers is not new,

and studies showed they are accurate to count steps and assess PA [8]. Then, re-

searchers have pointed out the effect of pedometers on motivation and PA [9]. Even

the presence of pedometers alone could increase walking steps, and feedbacks from

pedometers seem to be relevant information in order to involve motivation and DPA

[10]. Therefore, Biddle and Mutries [7] pointed that in other studies walking steps did

not increase significantly. In one of their studies they demonstrated that pedometers

provided a short-term effect, but that this effect was not evident in the long term.

Thus, all over the world, campaigns promoted the idea that 10,000 steps a day are

required for health, and pedometers seems to be a reliable technological support for

assessing DPA and providing feedbacks to people. Therefore, reported an overview

of 32 studies Biddle and Mutries pointed that 10,000 steps could be too low or too

high objectives for some people (active or sedentary individuals), so that the 10,000

steps goal might lead to reduce motivation, especially if people do not feel able to

reach this goal.

In accordance with these authors, we suggested that pedometers measures could

involve PA programs’ efficiency, because they allow to promote more adapted or

personalized step-goals.

115

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process

115

2.4 Conclusions

Research advances are particularly relevant to design intervention in DPA. There was

strong evidence that motivational support through social cognitive motivation frame-

work, self-regulation theory, or trans-theoretical model for behavioural change,

should increase DPA program effectiveness. Interventions should target behaviour

change by personalized and adapted interventions. Therefore, Interventions aiming at

increasing DPA are still problematic because:

a) Information about PA and health are relevant but few healthcare professionals are

trained to promote PA’s effects

b) PA program Intervention is efficient only if it is individually adapted or when

people is face-to-face

c) In most of countries it seems to be hard to change DPA in workplace settings

d) There was insufficient evidence that technology-based support interventions effec-

tively increased physical activity

Finally, the C2S project tried to take in account these advances. The global project is

described on the web, and many informational resources on PA and health are provid-

ed (www. agircontrelasedentarite.org). The C2S Project included a promotion initia-

tive, called “Challenging sedentary lifestyle”, gathering together many companies or

workplaces settings. Previous research showed that promoting DPA should consider

the workplace setting. Workplace could be an interpersonal setting which has poten-

tial for DPA changes, only if companies are members or partners of the project. In

2015, 20 local companies (in the west of France) and 318 employees participated

voluntarily in this ride.

The global project and the challenge need efficient technological support. A mo-

bile phone App (www.bouge-application.fr) was designed in order to deliver an indi-

vidually adapted program. The design process was theoretically based on motivational

and behavioural change frameworks. These frameworks and their implications for the

program will be presented in the second section.

The mobile phone application includes pedometer technology and may offer effi-

cient strategies aiming at taking into account a) initial or normal everyday steps

counts, b) individual motivational factor, and c) personally-adapted feedbacks. The

design process will be presented in the third section.

3 Enhancing Daily Physical Activity: Impact of Psychological

Factors

The development of exercise psychology has led to the proliferation of theories, pri-

mary tested in social and health psychology. Thus psychological factors of physical

activity have been studied extensively and helped us understand why people are moti-

vated or not (“amotivated”) and why they adopt a physically active lifestyle or not

(sedentary). The study of human motivation has been central to exercise psychology.

Vallerand and colleagues [11] offered an operational definition of motivation, consid-

ering some the following behavioural indicators: the initiation, the direction, the per-

sistence, the intensity, and continued motivation. These components of a motivated

116

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

116

behaviour could be influenced by social and cognitive factors.

More precisely, considering this perspective and previous empirical studies we

chose to take in account many models of motivation and behaviour in an exercise

setting. They were supposed to lead to principles for DPA program and to guide the

App’s design process. Thus each model we chose can be considered as a blend of

theoretical and practical support for our strategy and device. Consequently, our inter-

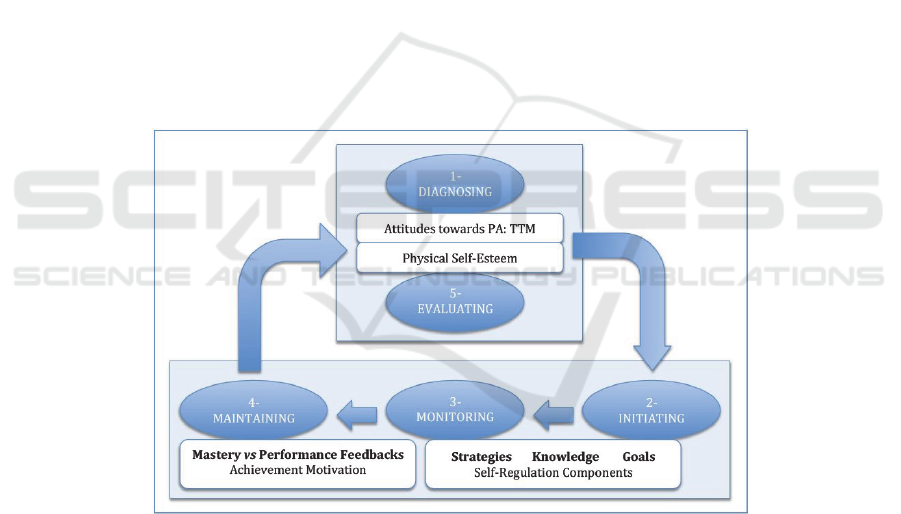

vention strategy consisted of five steps (see figure 1), including diagnosing, initiating,

monitoring, maintaining and evaluating. Each step has to be theoretically based, in

order to insure the all-strategy reliability.

3.1 Diagnosing Attitude towards Behaviour Change: The

Trans-Theoretical Model

The first model we took in account was the trans-theoretical model (TTM) of behav-

iour change. The TTM is not a model of motivation, but it as been classified as a

stage-based behavioural model [7]. The TTM was developed as a comprehensive

theory of behaviour change and was initially applied to smoking cessation [12]. The

TTM has been applied to physical activity, it could be considered as a precious tool

aiming at diagnosing the attitudes towards PA. The stages are [13]:

- Pre-contemplation: no intention to start physical activity

- Contemplation: considering starting physical activity

- Preparation: beginning a limited program of exercise

- Action: engaging in regular physical activity for less than six months

- Maintenance: engaging in regular physical activity for more than six months.

Studies [13] showed that TTM is a modest predictor of exercise.

Therefore, these stages are useful to diagnose if individuals are ready or not to ac-

cept the program; they should lead designers or practitioners to adapt their program.

In the TTM, the processes of change are the strategies used to progress along the

stages of change. The processes are divided into cognitive (thinking) and behavioural

(doing) strategies so that self-regulation theories should constitute a complementary

resource for modelling changes in DPA.

3.2 Initiating and Monitoring Behavioural Change: The Role of

Self-regulation Components

Aiming at understanding the initiation and the monitoring of behaviour, early at-

tempts in exercise psychology favoured theories of perceived control. One of the most

popular is the self-regulation theory advocated by Flavell [14]. Thus, goals, strategies,

metacognition and knowledge are considered as components within the self-

regulation process. Goals are considered as internal specific or general representations

of a desired state: people could try to involve daily steps, or to be more active; some-

times they want to please a parent or the doctor, or to take care of themselves. Re-

searchers interested in self–regulation showed that goals depend on prior knowledge

about the concerned domain, and on metacognition.

Knowledge about PA and health (sometimes researchers called them beliefs) de-

117

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process

117

termines motivation and behaviour towards PA. If someone knows that walking is the

most reliable way to well being, he might adopt goal to change his sedentary behav-

iour. Then, self-regulation theory describes a relationship between goals and behav-

ioural strategies: people whose goals are to enhance their DPA would adopt strategies

to walk everyday. Strategies are means or solutions that people imagine, or that

coaching should offer in order to reach a goal (e.g., walking during you’re phoning;

walking to get the next bus stop). These strategies are supposed to help people to

monitor and involve DPA.

Metacognition is simply defined as cognition about self [14]. People engaging in

metacognition will internally design knowledge about their own capabilities, and their

own skills. If someone knows that he is not able to walk more than 5,000 steps a day,

he spontaneously might not adopt a goal up to 10,000 steps a day. In contrary, if a PA

program is addressed to him, and seems too difficult, too high, he simply would give

up. Thus, metacognition is a precious component when designers want to select ap-

propriate goals and strategies in exercise settings [15]. In this perspective pedometers

should be helpful tools for people to know their own real DPA, and lead them to

adopt a relevant goal.

Complementary, when one wants to initiate PA, goal setting theory, and the self-

determination theory are also well-known resources. Research shows that motivation

for physical activity is likely to be more robust if environment offers choices and self-

determination rather than external control. This conducted us to consider that the

program should offer alternative goals. Individuals should be invited to choose the

best goals for themselves, or the most motivating one.

3.3 Maintaining Active Behaviour: Interest of Achievement Motivation

Because goals are personal representations, people are usually motivated through

various types of goals. According to the Achievement Motivation Theory goals and

behaviour could be referred to mastery – oriented or performance – oriented elements.

Closely related to the issue of Goal Achievement Motivation Theory, the climate, or

the relationships, within the exercise environment [16]. Perceptions of the motiva-

tional climate within a workplace or a training group can be classified as “mastery” or

“performance”. A mastery climate is one in which the participants perceive that self-

improvement is the most important. A “performance” climate is one where partici-

pants are often compared with each other or with normatively superior performance

(e.g. 10,000 steps a day).

A meta-analysis of climate studies across all physical activity settings quantified

the links between climates and outcomes [16]. The overall effects from fourteen stud-

ies involving over 4,000 participants showed a large effect for mastery climate on

positive outcomes and a moderate effect for performance climate on negative out-

comes.

Because feedbacks in a device are important elements of a perceived climate, this

line of research provides an important rationale for designing PA setting. Mastery

oriented feedbacks or performance oriented feedbacks should be addressed to partici-

pant depending to their personal motivation orientation or to their physical self-

esteem.

118

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

118

3.4 Evaluating Outcomes of DPA Intervention

Contemporary self-esteem theory proposes that our global view of ourselves (“global

self- esteem”) is underpinned by perceptions of specific domains of our lives, such as

social, academic and physical domains. Based on this approach and on Fox previous

work [17], Ninot et al., [18] has developed an operational measure of physical self-

perceptions and its self-perception subdomains of sport competence, perceived

strength, physical condition, and attractive body. Self – esteem theory proposed that

everyday events are likely to affect more specific perceptions of self, such as the be-

lief that one can walk 10,000 steps a day, which may eventually contribute to en-

hanced self-perceptions of physical condition or even physical self-worth. Self-

perceptions could be important psychological constructs guiding general motivated

behaviour, when people have to initiate PA. Self-perceptions can also be viewed, such

as consequences or outcomes of a PA program.

Finally both of Physical – Self Esteem Scale and TTM of behaviour change fur-

nished guides to implement the evaluation stage of the five-step intervention strategy.

3.5 Conclusions

The C2S Project aimed at implementing a technological solution, more specifically a

mobile phone application, based on advances from research in exercise psychology.

Fig. 1. The Five-Steps Strategy: a rationale for the App design process.

The program was considered as a set of personalized walking goals, behavioural

strategies and knowledge about PA and health, and daily-individualized feedbacks.

The question for the designer of a DPA program is how to deliver these information

or artefacts to individuals? The whole strategy and its backgrounds are summarized in

figure 1. These rational have been presented to the designers at the beginning of the

design process.

119

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process

119

4 Delivering a Personalized Physical Activity Program: A Design

Process

Despite an explosion of mobile phone applications concerning PA, few have been

based on theoretically derived constructs in order to promote health behaviours and

reduce sedentary behaviour [19].

During the period from September 2013 – May 2014, the interdisciplinary team

undertook initial app design, programming, and iterative user testing. Following these

activities, initial app was developed and feedbacks from potential users were ob-

tained. The Android smartphone platform was used. The smartphone battery life suf-

ficiently to allow continuous accelerometer data capture throughout the day. The data

collected via the smartphone's built-in accelerometer were transmitted to the project's

local servers each evening for data storage and to allow researchers to monitor the

quality of data while the design progressed. Feedbacks from users and ergonomic

analysis lead to involve the design. During the period from September 2014 – January

2015, a second version of the app, called MOVE (“BOUGE” in French language),

was developed, and was able to be commercialized. MOVE delivered an 8-weeks

program aiming at involving DPA

The 5-steps intervention strategy was implemented within the design of the App.

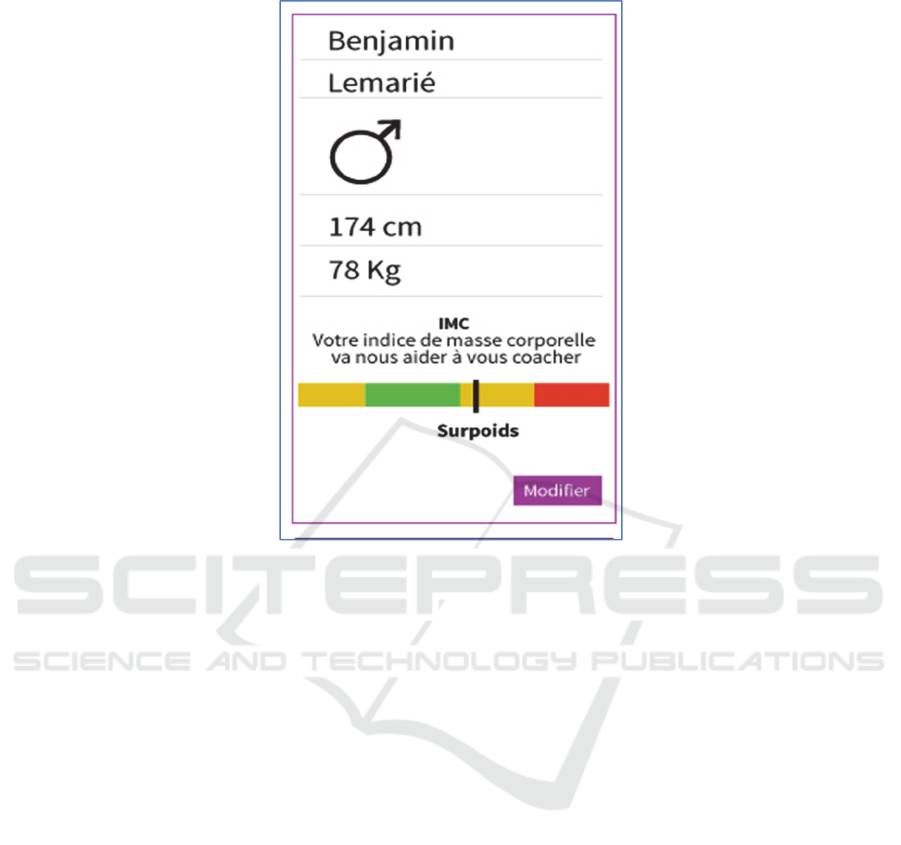

4.1 Diagnosing

The initial session is used to provide instruction on the general use of the App, and to

collect data including age, size, weight and gender. Especially, attitudes towards PA

and Physical Self-Esteem are diagnosed. The user has to answer the Physical-Self

Inventory (PSI-6), a six-item questionnaire developed and validated by Ninot et al.,

[18]. The PSI-6 is a short version of a previously validated questionnaire, the PSI-25,

adapted from the Physical Self-Perception Profile [18]. PSI-6 contains one item for

global self-esteem (GSE), one item for physical self-worth (PSW), and one item for

each of the four sub-domains identified by Fox and Corbin [17]: physical condition

(PC), sport competence (SC), attractive body (AB) and physical strength (PS). This

questionnaire was proven to reproduce the factorial structure of the corresponding

multi-items inventories [18] and to possess the same hierarchical properties. Each

item is a simple declarative statement, to which participants was invited to respond

using an analogic visual scale.

Attitude towards PA and behaviour change is measured using the stage of exercise

behaviour change scale, adapted from Cardinal [20]. Users are asked to place them-

selves in one the five stages. During this first week, descriptions of the physical activ-

ity recommendations for health and sedentary lifestyle risks are available on a single

screen.

The first week of the 12-weeks program is used as a baseline or a testing period

for delivering an adapted program. Users are requested to continue with their normal

physical activity and sedentary behaviours during the baseline week. The main screen

of the app provides the user’s current daily number of steps.

At the end of this initial week, the program can be personalized and users receive

goals and advices.

120

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

120

Fig. 2. User’s profile on a screen.

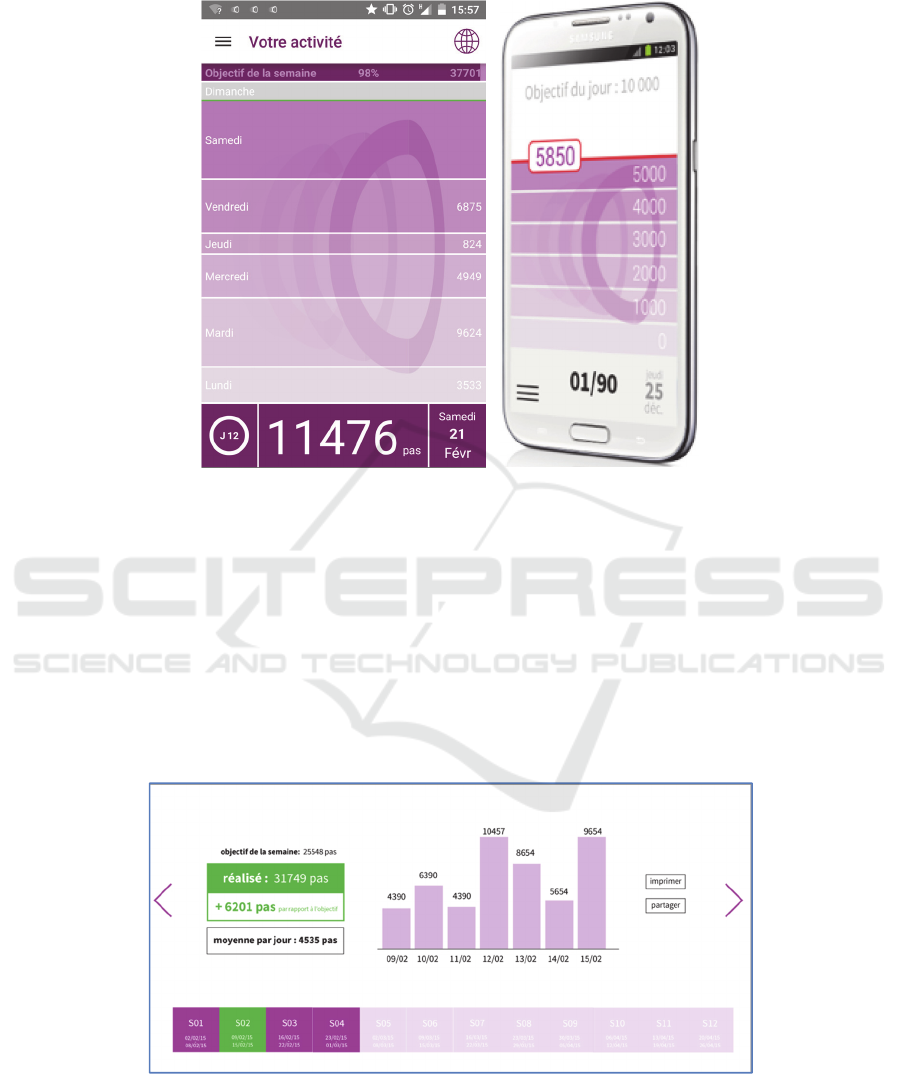

4.2 Initiating and Monitoring

At the beginning of each week, users receive specific goal setting, which emphasized

walking steps increase. For each week a distal goal is assigned depending both based

on the score or number of walking steps the user reached at the end of previous week

(e.g., 30 000 steps a week), and on his psychological profile (i.e., Physical Self-

Esteem score). Depending on previous data, 5, 10, 15, 20% enhancement in weekly

walking steps was used as references points. Participants were provided with three

goal options of varying difficulty (e.g., 33 000 steps, or 34 500 steps, or 36 000 steps).

These choice options were given based on the self-determination and goal-setting

theory principles.

Whenever he wants, the user can see on the same screen his just-in-time score, the

score for previous days, and the target at the end of the week.

In addition to having access to some “help” as part of this app, users participants

can edit a set of behavioural strategies. On a specific screen, written solutions for

increase DPA are listed and the user is invited to choose some of them. Twice a day

brief health information and knowledge about benefits of PA (e.g., 1 minutes for PA =

10 minutes for life) are displayed.

Thus, goals, knowledge and strategies are supposed to stimulate self-regulation be-

haviour aiming at initiating and monitoring DPA.

121

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process

121

Fig. 3a and 3b. User’s daily current screens.

4.3 Maintaining

It was attempted that personalized feedback delivered by the app aim maintain moti-

vation and PA. Balance sheets are provided in the middle of the fourth, the eighth and

the eleventh week of the program. An email is sent to the user including graphs and

encouragements or advices. Feedbacks’ content depends on scores and on psycholog-

ical profile. Thus they can be mastery – oriented (e.g., Congratulations! An increase

of 15% over the previous weeks! Go on! You walk for your health!), or performance

– oriented (Congratulations! You’ve reached 50 000 steps a week! You’re now con-

sidered as an active person!).

Fig. 4. User’s balance sheet.

122

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

122

4.4 Evaluating

In line with previous research in exercise psychology, pedometers are reliable for

furnishing a realistic and objective measure about everyday walking steps. Such an

on-going evaluation is supposed to impact motivation and behaviour control. Users

perceived the gap between the goal they have chosen and their own DPA. Conse-

quently, self-regulation mechanisms consist in imagining solutions, imitating pairs’

behaviour, seeking for advices. The app helps people in taking in charge their own

behaviour.

Finally, as soon as the program is closed, users receive a final balance sheet and

advices for future. This constitutes a milestone in our 5-steps strategy; when someone

is able to evaluate his own progress, it was hypothesized that his own self-perception

would enhance. Thus at the end of the program, users are asked to answer the Physi-

cal Self-Esteem. If users observe increases concerning both of DPA and Physical

Self-Esteem, they would get confidence in the device effectiveness. These psycholog-

ical effects would favour continued motivation for DPA.

5 Perspectives

Benefits of Physical Activity are attempted for adults in the European Space. The C2S

Project including a web resource, a ride for companies called “Challenging sedentary

lifestyle”, and the MOVE App, is a medical, technologic and scientific project. Thus,

an empirical study (200 participants in experimental group vs 100 participants in

control group) has been conducted to assess the effect of the program on DPA. Re-

sults could have important implications for advancing the field of PA sciences, and

will be precious to involve the design of the App. Moreover collected data on daily

PA or behaviour changes in a workplace setting will be stored and should be useful

for health institutions.

References

1. O'Donovan, G. , Blazevich, A., Boreham, C., Cooper, A.H., Crank, H., Ekelund, U., Fox,

K.R., Gately, P., Giles-Corti, B., Gill, J.M.R., Hamer, M., McDermott, I., Murphy, M.,

Mutrie, N., Reilly, J.J., Saxton, J.M. and Stamatakis, E. : The ABC of Physical Activity for

Health: A consensus Statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Scienc-

es. J. of Sports Sc. 28, 6 (2010) 573-591

2. Blair SN. : Physical Inactivity: the Biggest Public Health Problem of the 21st Century. Br.

J. Sport. Med. 43 (2009) 1–2

3. Varo, J.J., Martinez-Gonzalez, M-A.: Current Challenge in the Research About Physical

Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle. Rev Esp Cardiol. 60 (2007) 231-233

4. Williams, P.T. and Thompson, P.D.: Walking vs Running for Hypertension Cholesterol,

and Diabete Risk Reduction. Art. Thomb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 5, (2013) 1085-1091.

5. Kahn, E. B., Ramsey, L. T., Brownson, R. C., Heath, G. W., Howze, E. H., Powell, K. E.,

Stone, E. J., Rajab, M. W. and Corso, P.: The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase

Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Am. J. of Pre. Med. 22 (2002) 73–107.3.

6. Hillsdon, M., Foster, C., Naidoo, B. and Crombie, H.: A Review of the Evidence on the

123

Mobile Phones App to Promote Daily Physical Activity: Theoretical Background and Design Process

123

Effectiveness of Public Health Interventions for Increasing Physical Activity Amongst

Adults: A Review of Reviews. London: Health Development Agency (2003).

7. Biddle, S. J. H. & Mutrie, N.: Psychology of Physical Activity. Determinants, Well-being

and Intervention. 2

nd

Edition, Routledge, New-York and London (2008).

8. Crouter, S., Schneider, P., Karabulut, M. And Basset, J.: Validity of 10 Electronic Pedome-

ters for Measuring Steps, Distance, and Energy Cost. Med. Sc. In Sp. and Ex. 35, 8 (2003)

1455–60.

9. Rooney, B., Smalley, K., Larson, J. and Havens, S.: Is knowing Enough? Increasing Physi-

cal Activity by Wearing a Pedometer. Wis. Med. J. 102, 4 (2003) 31–6

10. Stovitz, S., VanWormer, J., Center, B. and Bremer, K.: Pedometers as a Means to Increase

Ambulatory Activity For Patients Seen at a Family Medicine Clinic. J. Am. B. of Fam.

Prac. 18 (2005) 335–43

11. Vallerand, E.L., Pelletier, R.J., and Ryan, L.G.: Motivation and Education: the Self-

Determination Perspective. The Ed. Psy. 26 (1991) 325-346

12. Prochaska, J. O. and DiClemente, C. C.: Transtheoretical Therapy: Toward a More Integra-

tive Model of Change. Psychotherapy: Th. Res. and Prac. 19 (1982) 276–88

13. Callaghan, P. Khalil, E. and Morres, I.: A Prosective Evaluation of th Transtheoretical

Model of Change Appled to Exercise in Young People. Int. J. of Nurs. St. 47 (2010) 3-12

14. Flavell, J. H. Cognitive monitoring. In: Dickson, W. P. (Ed.): Children’s oral communica-

tion skills. New York: Academic Press (1981)

15. Kermarrec, G., Todorovitch, J. and Fleming, D.: Investigation of the Self - Regulation

Components Students Employ in the Physical Education Setting. J. of Teach. in Phys. Ed.

2, 23 (2004) 23-142

16. Ntoumanis, N. and Biddle, S. J. H.: A Review of Motivational Climate in Physical Activity.

J. of Sp. Sc. 17 (1999) 643–65

17. Fox, K.H. and Corbin, C.B.: The Physical Self-Perception Profile: Development and pre-

liminary validation. J. of Sp. and Ex. Psy. 11, (1989) 408-430

18. Ninot, G., Fortes, M., and Delignières, D.: Validation of a Shortened Assessment of Physi-

cal Self in Adults. Perc. And Mot. Skills 103 (2006) 531-542.

19. King, A.C., and al.: Harnessing Different Motivational Frames via Mobile Phones to Pro-

mote Daily Physical Activity and Reduce Sedentary Behaviour in Aging Adults. Plos One

8, 4 (2013) 1-8

20. Cardinal, B.J.: Construct Validity of Stages of Change for Exercise Behaviour. Am. J. of

Health Prom. 12, 1 (1997) 68-74

124

EPS Rome 2014 2014 - European Project Space on Computational Intelligence, Knowledge Discovery and Systems Engineering for Health

and Sports

124