Understanding Information Technology Security Standards Diffusion

An Institutional Perspective

Sylvestre Uwizeyemungu

1

and Placide Poba-Nzaou

2

1

Département des Sciences Comptables, UQTR, 3351, boul. des Forges, Trois-Rivières (Québec), Canada

2

Département d’Organisation et Ressources Humaines, ÉSG UQAM, 315, Ste-Catherine Est, Montréal (Qc), Canada

Keywords: IT Security, Information Security, Security Standards, Institutional Theory, Standards Diffusion, ISO

27000.

Abstract: Organizations' dependency on information technology (IT) resources raises concerns over IT

confidentiality, integrity, and availability. IT security standards (ITSS) which play a key role in IT security

governance, are meant to address those concerns. It is then important for researchers, managers, and policy-

makers to understand the reasons for the low levels of ITSS diffusion in organizations. Building on

institutional perspective, this study shows that none of the ITSS has yet reached the stage of legitimation

that would prompt a widespread diffusion across organizations. Of particular focus is the benchmarking of

ISO/IEC 27000 against other more diffused ISO generic standards. Three methodological approaches were

used: structured documentation analysis, public secondary data analysis, and informal interviews of experts.

This study sensitizes managers and policy-makers to the key role of institutional mechanisms in shaping

ITSS diffusion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Organizations in modern societies rely heavily on

Information Technology (IT) to perform a wide

range of activities from basic, and routine operations

to highly complex and critical ones. Yet, IT-

dependent operations are exposed to IT

vulnerabilities and to threats of different kinds.

Vulnerabilities refer to weaknesses in one or more

parts of an IT system, whereas threats refer to

possible dangers directed towards the system (Chang

et al. 1999). In recent years, numerous IT-related

incidents have been reported by many IT managers:

virus incidents (49%), insider abuse of computer

systems (44%), and unauthorized access from

external sources (29%) (Hu et al. 2011). Current

surveys have systematically reported a dramatic

increase in cybercrime-related incidents (PwC,

2013; Singleton, 2013).

Organizations try to deal with all these issues

through IT security governance which refers to

mechanisms, technologies, structures, and policies

combined together in order to ensure that the

organization’s IT assets in all their components such

as software and hardware, data and information, and

people respond constantly to required levels of

availability, confidentiality and integrity (von Solms,

2005). Organizations’ dependence on IT makes IT

security governance an important issue. By all

accounts, IT security standards (ITSS) recognized at

industrial, national, or international levels are

essential for organizations aiming to effectively

implement IT security-related mechanisms,

technologies, structures, and policies (Disterer,

2013; Hone and Eloff, 2002).

Given the importance of ITSS, one would expect

to find a high rate of ITSS diffusion in

organizations. This, however, is not the case: for

example, when compared to quality system

standards (ISO 9001) and environmental

management standards (ISO 14001), certification

levels of ITSS (ISO/IEC 27000) are very low.

Statistics released by ISO show that while ISO 9001

and ISO 14001 could display respectively 1,101,272

and 285,844 certifications worldwide in 2012,

ISO/IEC 27000 was limited to a meager number of

19,577 certifications; that is 1.8% and 6.9% of

respectively quality and environmental standards.

This means that for 100 firms certified ISO 9000 one

finds less than 2 firms with ISO IT security

certification, and the ratio is 100 firms certified ISO

14000 for 7 certified ISO 27000. One would argue

that the lower diffusion of ISO 27000 is simply due

to its being launched later (ISO 9000 was launched

5

Uwizeyemungu S. and Poba-Nzaou P..

Understanding Information Technology Security Standards Diffusion - An Institutional Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0005227200050016

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP-2015), pages 5-16

ISBN: 978-989-758-081-9

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

in 1987, ISO 14000 in 1996, and ISO 27000 in

2005). We will show that this argument does not

hold by comparing the respective evolutions of the

above-mentioned standards in the first seven years

following each ISO launch. More significant are the

results of surveys showing that even the level of

awareness of ITSS is low. For example, a 2008

survey in the UK showed that only 21% of

businesses were aware of ISO 27000 series, and

among them, only 30% had the standards fully

implemented (Tsohou et al., 2010). The low level of

awareness among top managers, including CIO

(chief information officers) or CTO (chief

technology officers), with regard to “key

cornerstones of a strong cyber-security program” is a

great concern (PwC, 2013, p. 4).

Considering the utmost importance of IT security

in today’s business activities, and the important role

that ITSS play in ensuring IT security, it is necessary

for researchers and practitioners to understand why

the diffusion of ITSS in organizations remains low.

This leads to our research question: “why the

diffusion of IT security standards in organizations is

low in spite of their acknowledged importance?”

Justifications one finds in IT security literature to

explain this situation are all substantive in nature

(Wood and Caldas, 2001); that is based on “rational”

reasons for which the implementation of the

standard would be deemed impossible or

inappropriate. Examples of such substantive

reasoning include limitations associated to extant

standards (Siponen, 2006a; van Wessel et al., 2011),

financial considerations or low incentives (Gillies,

2011). This paper proposes an alternative

explanation rooted in institutional theory: based on

the analysis of the historical evolution of different

ITSS worldwide, we contend that none of them has

reached the “stage of legitimation” (Lawrence et al.,

2001, p. 627) that would be characterized by a wide

diffusion of one or a few of available ITSS across

organizations. We analyze in particular statistics of

ISO certifications in North America (Canada and

USA) in relation to the bulk of registered

corporations in the same region. Then, we proceed

to a benchmarking of ISO 27000 evolution against

the evolution of other ISO generic standards, namely

ISO 9000 and ISO 14000. Our results indicate that if

nothing is changed with regards to current

institutionalization mechanisms, the ITSS diffusion

will remain very low. An important implication of

this study is to make different stakeholders sensitive

to the key role of institutional mechanisms in

shaping ITSS diffusion as ITSS are deemed essential

to implement sound security measures commensu-

rate with the security challenges of the modern

information-dependent economies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as

follows: in the theoretical and empirical background

of our study, we briefly present the institutional

perspective which is the cornerstone of our analysis

of the diffusion of ITSS. We then present our

methodological approaches; followed by a section

devoted to results presentation and analysis which

includes the mapping of the broad ITSS historical

evolution, the analysis of their institutionalization

process, and the benchmarking of ISO 27000 against

quality and environment standards. The final two

sections will respectively cover the discussion of our

results, and our concluding remarks.

2 THEORETICAL AND

EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Institutional Perspective

The diffusion of IT security standards can be

analyzed through the lens of institutional theory,

according to which external or environmental

pressures play a significant role in the diffusion of

innovations in organizations. Besides being

economic systems driven by the pursuit of economic

efficiency and performance, organizations are also

social and cultural entities driven by the necessity to

meet expectations from their direct and indirect

environment, and gain in the process some

legitimacy. The notion of legitimacy is central to the

institutional theory (Cousins and Robey, 2005): for

their survival, organizations need more than

production resources (capital, labor), they also need

acceptance by informal and formal networks in

which they are embedded, and they seek this

acceptance (or legitimacy) by adjusting themselves

to a number of regulations, norms, practices, values,

and beliefs prevalent in those networks.

This tendency of organizations evolving in the

same environmental context to adopt the same

practices, rules, and norms for the sake of legitimacy

is known as institutional isomorphism which can be

of coercive, mimetic, or normative nature

(DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). The adoption of

innovations, such as ITSS, is no exception to this

phenomenon. The adoption of an innovation will be

qualified as coercive isomorphism whenever it is

due to pressures (which can be more or less

“gentle”) from business partners, relations or

regulations; it is referred to as normative

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

6

isomorphism when it stems from the influence of

professional training or communities of key

employees or managers; it is labeled as mimetic

when it is based on following other organizations

seen as models or references, or based on alignment

to standardized solutions or common practices

generally known as “best practices”. These “best

practices” can be spread through consultancy or

accounting firms. Analyzing the diffusion of the

British IT security standard (BS 7799) Backhouse et

al. (2006) ruled out coercive forces arguing that

there were no laws in the UK making it mandatory

for organizations to adopt the standard. However,

coercive pressures are more than just laws. They can

manifest themselves in forms of “obligatory passage

points” which refer to the requirement that an

organization “A” complies to a given standard in

order to be allowed to do business with an

organization “B” (Backhouse et al., 2006, p. 415).

As for example, national IT security standards

promoted by government agencies have mainly been

developed in this spirit for government contractors.

2.2 The Concept of Institutional Field

In institutional theory, isomorphic mechanisms

operate between organizations belonging to an

organizational field, or institutional field (DiMaggio

and Powell, 1983; Lawrence et al., 2001), that is a

network of organizations that form a recognized area

of institutional life due to their area of expertise or

activity, or relationships they may have (suppliers,

customers, regulatory agencies, competitors, etc.).

The study of the diffusion of an innovation with

regards to the institutional field allows for the

inclusion of all relevant actors or stakeholders in the

analysis. Therefore, in the context of ITSS diffusion,

it is important to consider the relevant institutional

field.

Working from the statistics provided by ISO,

previous studies generally analyze the evolution rate

of certifications from one year to the next; they point

out the increasing pace of ISO 27000, and conclude

to its strong diffusion (Disterer, 2013; Tsohou et al.,

2010). The numbers of certifications of year n are

compared to the number of certifications of year n-1,

without any reference to the bulk of organizations

that are targeted. Such analysis does not take into

account the institutional field and therefore leads to

a somewhat misleading conclusion: the high rate of

increase observed year after year masks the fact that

the ISO 27000 certification remains a marginal

phenomenon among potential adopting organiza-

tions, even after a period of seven years. The

institutionalization of an innovation or practice can

only be conceived relative to the field of its potential

application, and in the case of generic standards like

ITSS, one can assume that all organizations,

regardless of their sector, are potential targets. This

assumption has been explicitly or implicitly made

for other ISO generic standards, ISO 9000 and ISO

14000 (Franceschini et al., 2006; Francceschini et

al., 2004; Marimon et al., 2010).

2.3 Institutionalization Process and

Mechanisms

The institutionalization of an innovation generally

follows a process in four main stages labeled

innovation, diffusion, legitimation, and

deinstitutionalization (Lawrence et al., 2001). The

innovation phase refers to the early stage when a

new practice or technology emerges and is adopted

by few organizations. A parallel can be made

between the innovation phase and the pre-

institutionalization and theorization stages of

institutional change according to Greenwood et al.

(2002). The diffusion phase refers to the period

when the innovation gains momentum within a field

and is extensively adopted by organizations. With

the legitimation phase, the innovation reaches the

point of saturation and is widely considered as a

taken-for-granted practice in organizations (Enrione

et al., 2006). Finally, the deinstitutionalization phase

is when the innovation loses its legitimacy due to

“precipitating jolts” in form of social, technological,

or regulatory changes (Greenwood et al., 2002, p.

60).

Analyzing temporal patterns of institutionaliza-

tion, Lawrence et al. (2001) contend that the pace

and stability of any institution hinges on the

institutionalization process supporting mechanisms

used. The main concepts defined by these authors, as

well as the institutionalization mechanisms with

their respective temporal effects are presented in

Table 1.

Combining the mode of power (episodic vs

systemic) exercised by the institutional agent and the

relationship of power this agent assumes with regard

to targeted actors (object vs subject), Lawrence et al.

(2001) offer a much more granular conceptualization

as opposed to the general conceptualization

proposed by DiMaggio and Powell (1983).

Lawrence et al. (2001) identify four mechanisms of

institutionalization: influence, force, discipline, and

domination. With influence-based mechanisms, the

institutionalization process is slow and the resulting

institutions less stable; a force-based institutionali-

UnderstandingInformationTechnologySecurityStandardsDiffusion-AnInstitutionalPerspective

7

zation is very fast but less stable; a discipline-based

institutionalization is characterized by a slow pace

and a high stability, while a fast pace and a high

stability are related to a domination-based

institutionalization. The authors also explore two

combinations of mechanisms: the combination of

influence and discipline-based mechanisms results in

a medium pace and a high stability institutionali-

zation, while the combination of force and

domination-based mechanisms yields a very fast

pace and a high stability institutionalization.

3 METHOD

Three main methods were used for this research, that

is structured documentation analysis, public

secondary data analysis (statistics), and informal

exchanges (e-mails and discussions). The

combination of these three methods was necessary to

identify the pace of ITSS institutionalization process

and to make sense of the actual state of

institutionalization.

For mapping the ITSS historical evolution, we

analyzed the relevant literature with the aim of

identifying instances of institutionalization

(Lawrence et al., 2001). This historical approach

was necessary as “it is impossible to understand an

institution adequately without an understanding of

the historical process in which it was produced”

(Selznick et al., 1967: in Scott, 1987).

Documentation analysis has been previously and

successfully used in studies applying institutional

theory (Cousins and Robey, 2005; Enrione et al.,

2006).

To identify the relevant literature, we used a

structured approach for literature review proposed

by Webster and Watson (2002). We performed a

topic-based search using two major journal

databases, the ABI/INFORM Global (ProQuest) and

Information Science & Technology Abstracts

(ISTA). We applied a cross-combination of search

terms. Each of the terms “information security”,

“information technology security”, “IT security”,

“information system security”, and “IS security” was

combined with each of the terms “standard”,

“certification” or “certificate”. The search aim was

to determine the presence of combined terms in

peer-reviewed article titles and abstracts. The

original search yielded 84, and 61 articles

respectively for ABI/INFORM and ISTA.

Based on titles and abstracts analysis, we

eliminated duplicates and irrelevant articles, and

then conducted a backward search in the citations of

Table 1: Concepts and Mechanisms of Institu-tionalization

with Associated Temporal Effects (Elaborated from

Lawrence et al. 2001).

Dimension Type Definition

Mode of

power

Episodic Relatively discrete, strategic acts

of mobilization initiated by serf-

interested actors

Systemic Forms of power that work

through routine, or through

ongoing practices of

organizations (e.g. socialization,

accreditations, technological

systems, insurance and tax

regimes)

Relationship

to target

Subject Target of power is assumed to be

capable of agency (ability to

choose)

Object The power does not require

choice on the part of its target

(actor incapable of choice, or

whose choice is irrelevant to the

exercise of power)

Temporal

dimensions

of

institutiona-

lization

Pace Length of time taken for an

innovation to become diffused

throughout an organizational

field

Stability Length of time over which an

institution remains highly

diffused and legitimated

Mechanisms

of

institutiona-

lization

Mecha-

nism

Combi-

nation

Result (Pace,

Stability)

Influence Episodic X

Subject

P-, S-

Discipline Systemic X

Subject

P-, S++

Force Episodic X

Object

P+++, S-

Domina-

tion

Systemic X

Object

P++, S++

Combined

mecha-

nisms

Influence +

Discipline

P+, S++

Force +

Domination

P+++, S++

Legend. P: Pace; S: Stability; -: Low or Slow; +: Medium; ++:

High or Fast; +++: Very Fast

already identified articles. At the end of this process

we had 17 articles from which we were able to map

the ITSS evolution. This analysis was completed by

information gathered from documents available

through the websites of major international bodies

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

8

related to IT security standards such as ISO and

Information Security Forum (ISF).

The collected documents were read, re-read, and

cross-checked. After several iterations, we were able

to develop a deep understanding of the historical and

spatial background of the ITSS evolution in

organizations.

We also analyzed public statistics on ISO generic

standards. ISO statistics have been widely used in

multiple scholar researches, and are deemed reliable

(Marimon et al., 2010). We compared the

certification statistics of ISO/IEC 27000 with those

of other generic standards (ISO 9000 and ISO

14000) worldwide and in North America (Canada +

USA), in order to highlight the relatively slow

institutionalization of the security standard. We also

compared ISO certification statistics in North

America with statistics on registered enterprises

from Statistics Canada and the Census Bureau of

Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB).

The benchmarking of ISO/IEC 27000 against

ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 makes sense for at least

three reasons. First of all, the three standards are

cross-industrial (generic) in nature: they are referred

to as meta-standards (Heras-Saizarbitoria and Boiral,

2013) that can be adopted by organizations

regardless of their sector of activity. The second

reason is that they all benefit from the international

recognition endowed by the brand ISO. The third

reason is that while ISO 27000 is relatively recent

and its adoption in organizations poorly researched,

the adoption of ISO 9000 and to some extent ISO

14000 have been extensively researched and thus

offer a solid basis for benchmarking.

Throughout the research process, we maintained

informal contacts (through e-mails, by phone and

with in person discussions), with three main sources:

4 representatives of certifications bodies in North

America (Canada + USA), 2 representatives of

statistics agencies (1 in Canada, and 1 in USA), and

2 IT security professionals working for 2 different

Canadian manufacturing firms. Informal

conversations or interviews have proven to be

valuable in complement with other methods (Sarker

and Lee, 2002); in our study, they helped make

sense of the diffusion patterns found using statistics

and documentation analysis.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Historical Evolution of ITSS

As stated earlier, based on a literature review, we

have identified multiple information or ITSS and

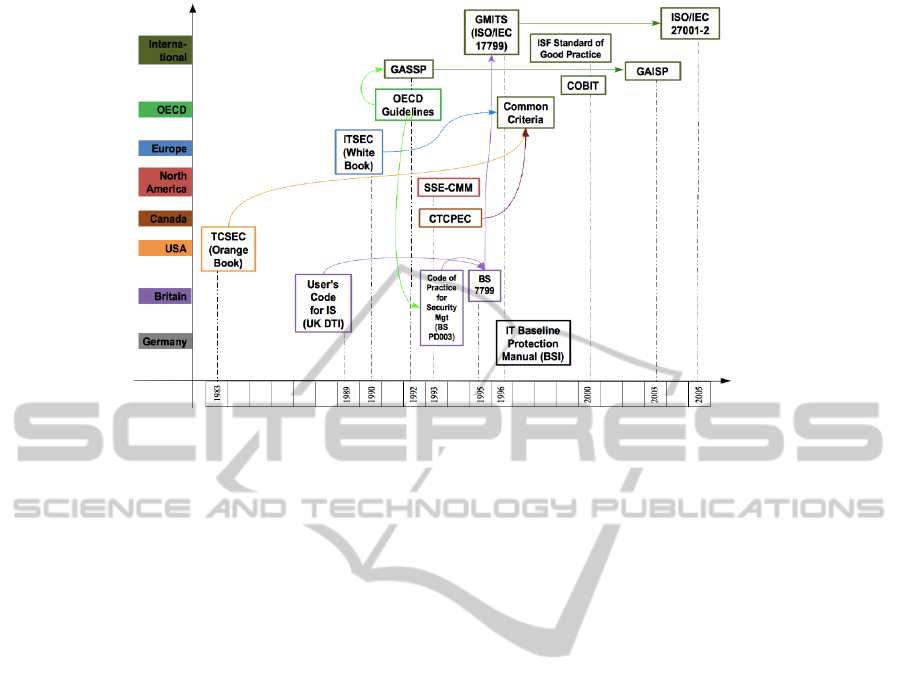

how they have evolved. Figure 1 presents the ITSS

by region of origin, the time of their initial

development, their evolution and links with other

standards.

The first standard, the Trusted Computer

Security Evaluation Criteria (TCSEC), also known

as “Orange Book”, appeared in 1983 promoted by

the US department of defence (von Solms, 1999). A

few years later, in 1989, the UK Department of

Trade and Industry (UK DTI) published the “User’s

Code of Practice for Information Security” (Gillies,

2011).

In 1992, the Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development (OECD) published its

Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems

(Orlowski, 1997). As a means of implementing these

OECD guidelines (Ibid), the UK DTI, in 1993,

published a “Code of Practice for Security

Management” (BS PD 003) which eventually

evolved, in 1995, into BS 7799 (Backhouse et al.,

2006; von Solms, 1999), considered as the first de

jure standard (Smith et al., 2010), and widely spread

in the UK, New-Zealand, South-Africa, and

Australia (Siponen and Willison, 2009).

In 1996, in a joint effort, ISO and the

International Electro-technical Commission (IEC)

transformed the BS 7799 into an international

standard, the Guidelines for the Management of IT

Security - GMITS (ISO/IEC 17799) (Backhouse et

al, 2006; Siponen and Willison, 2009) which will

become, in 2005, ISO/IEC 27000 (Gillies, 2011).

Meanwhile, in response to the American

standards (Abu-Musa, 2002), the European

Commission (EC) and the Canadian government

issued their own standards, respectively in 1990 and

1993: the Information Technology Security

Evaluation Criteria (ITSEC), also known as “White

Book” (von Solms, 1999) for the EC, and the

Canadian Trusted Computer Product Evaluation

Criteria (CTCPEC).

The SSE-CMM (System Security Engineering -

Capability Maturity Model), well known in North

America, was developed in 1993 under the

sponsorship of the US National Security Agency

(NSA) in tandem with the International Systems

Security Engineering Association (ISSEA) (Siponen

and Willison, 2009).

The IT Baseline Protection Manuel is another well

known standard. It was first developed in 1996 (von

Solms, 1997) by the German Bundesamt für

Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik (BSI) [German

federal agency for security in information

technology] and it is, in its 2000 version, a federal

UnderstandingInformationTechnologySecurityStandardsDiffusion-AnInstitutionalPerspective

9

Figure 1: IT Security Standards - Origin, Links, and Evolution.

agency for security in information technology] and it

is, in its 2000 version, a nationally recognized

standard in Europe (Brooks et al, 2002; Hone and

Eloff, 2002).

In 1996, the Common Criteria emerged when

three previous standards, the American TCSEC, the

European ITSEC, and the Canadian CTCPEC were

combined (Whitmore, 2001). The Common Criteria

is also recognized as ISO/IEC 15408 (Caceres et al.,

2010; Tsohou et al., 2010).

The Generally Accepted Systems Security

Principles (GASSP-1992, GASSP-1999), later

known as Generally Accepted Information Security

Principles (GAISP-2003) (Siponen, 2006a; Siponen,

2006b) is another international standard. Its

development was based on OECD principles (Poore,

1999; Siponen and Willison, 2009), and was

supported by US Government and the International

Information Security Foundation in conjunction with

several organizations around the World (Hone and

Eloff, 2002; Siponen, 2006b).

There are two other international standards

published in 2000 (Hone and Eloff, 2002): the ISF’s

Standard of Good Practice by the Information

Security Forum in 2000, and the Control Objectives

for IT and Related Technology (COBIT) developed

by the Information Systems Audit and Control

Association (ISACA).

4.2 Analysis of the General

Institutionalization Process of ITSS

From the analysis of the broad IT security standards

(ITSS) evolution presented earlier, one can draw

some conclusions with regards to the timeline of

their development. Three main periods can be

clearly identified and labeled:

•

The genesis phase or initial development phase

(1980-1990): it is in this decade that the first major

standards were developed, when integrated IT

security frameworks instead of mere checklists

were proposed (Siponen, 2006b).

•

The proliferation phase (1990-1995): during this

relatively short period, other standards appeared

and the first major efforts to go beyond the

national boundaries took place.

•

The internationalization phase (1995-2005): this

period is characterized by more effort either to

combine national and regional standards into more

international standards, or to propose others by

international groups.

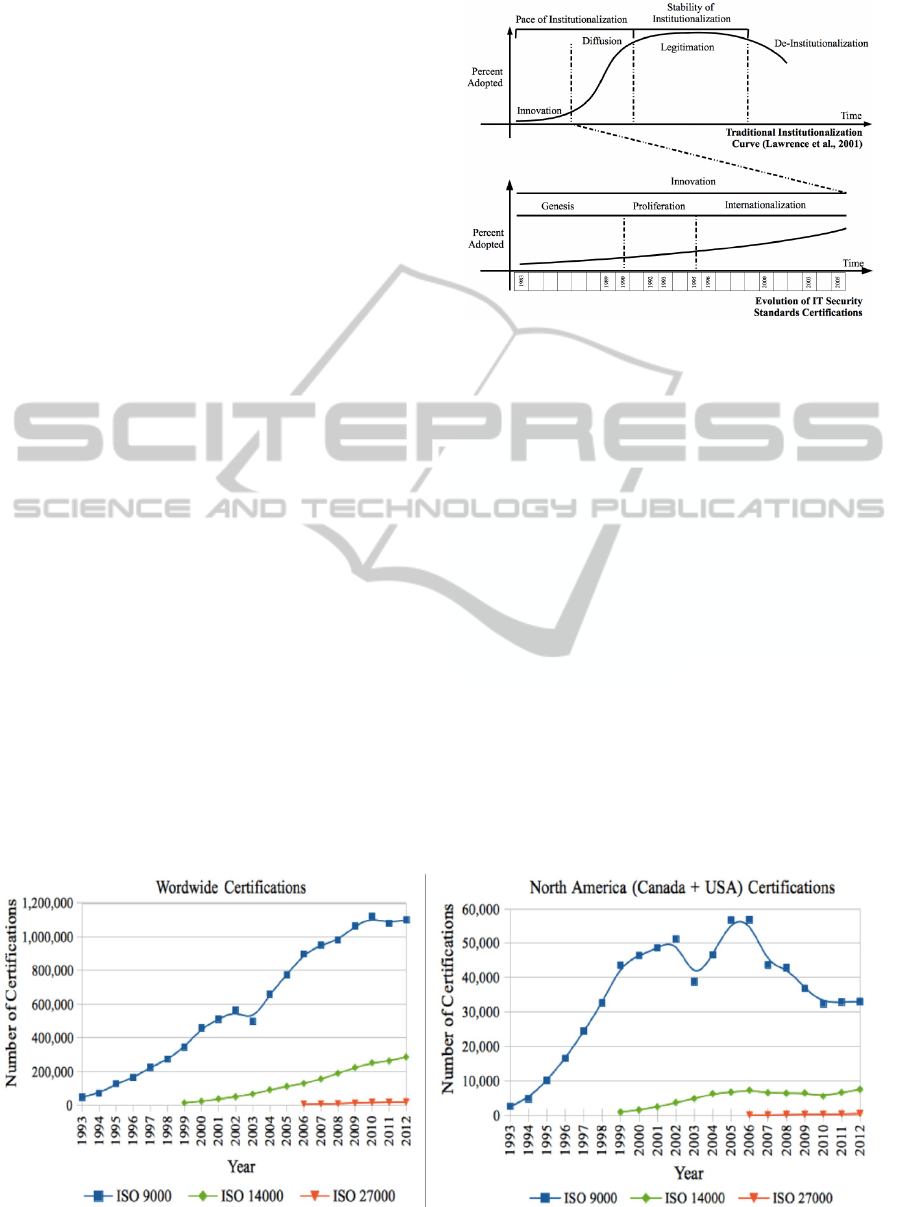

Statistics from ISO can help us illustrate the

stage of the institutionalization process of ITSS. We

used ISO/IEC 27000 (which we will refer to from

now on as ISO 27000) due to its international status

and to the availability of data. We compare statistics

on ISO 27000 certifications in North America with

statistics on registered corporations which are

theoretically potential adopters of the standards.

ISO statistics show that in 2010, Canada and the

USA counted respectively 26 and 247 ISO 27000

certifications. Considering that registered enterprises

the same year were respectively 2,428,270 and

8,162,808 (from the statistics agencies of both

countries), one notes that the diffusion rate of the

standard in North America is insignificant

(respectively 0.001% and 0.004%). Considering that

the low level of ISO 27000 diffusion is largely

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

10

echoed in prior studies for different ITSS (Gillies,

2011; Tejay and Shoraka, 2011, van Wessel et al.,

2011), one would assume that ITSS have not yet

reached the diffusion phase on the

institutionalization curve (cf. Figure 2). All the

above-mentioned periods of ITSS evolution

(genesis, proliferation, internationalization) can be

considered as different steps of the innovation phase

of the traditional institutionalization curve. It is

worth noting that sometimes the institutionalization

process does not go past the innovation phase. This

was the case for example with the “c:cure

certification scheme against BS7799 Part 2”, an

initiative launched in April 1998 in UK and

discontinued in 2000 due to low adoption rate

(Backhouse et al., 2006, p. 423).

Another conclusion from the analysis of the

evolution of ITSS is that, although the

internationalization of standards seems to have been

a major trend for the last years (no more exclusively

national standards have been developed in recent

years), many international standards coexist: the

internationalization process does not seem to lead to

unification of standards, though we do not assume

that a unique international ITSS would be

preferable, but the question deserves analysis. As

political actions, power games, and groups interests

play a much more influential role than economic or

rational reasons in the process of acquiring an

international status (Backhouse et al., 2006), the

validity or the legitimacy of maintaining multiple

international standards may be questioned with

regards to economic or security effectiveness. When

viewed from an institutional theory perspective, it is

clear that the coexistence of multiple standards

indicates that none has yet clearly established its

legitimacy over others.

Figure 2: Comparing the Evolution of IT Security

Standards Certifications Against the Traditional Institutio-

nalization Curve.

In terms of expectations for the mid- and long-

term future of ITSS in general, and for ISO 27000 in

particular, we note that as ISO 27000 has been

launched years after other generic standards, namely

quality (ISO 9000) and environment (ISO 14000)

were launched and from which certification statistics

are available for much more longer periods, insights

from the latter can probably help us understand the

former’s evolution thus far, and eventually predict

its future evolution. As well, there are more scholar

studies on ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 than on ISO

27000 (Fomin et al., 2008).

4.3 ITSS Diffusion: Benchmarking of

ISO Security Standard against ISO

Quality and Environment

Standards

Based on statistics from ISO, Figure 3 presents the

Source: Adapted from ISO Survey 2012.

Figure 3: Evolution of ISO Generic Standards Certifications.

UnderstandingInformationTechnologySecurityStandardsDiffusion-AnInstitutionalPerspective

11

evolution of certifications for the three standards

worldwide and in North America. The debuts of ISO

27000 and its evolution rate appear to be more

modest compared to ISO 14000, and more so when

compared to ISO 9000.

Taking into consideration the institutional field

as referred to earlier, we present a portrait of the

magnitude in the diffusion of certifications among

companies that are potential targets of ISO generic

standards. Figure 4 presents the percentage of

enterprises certified in North America for each

generic standard and for the first 5 years for which

ISO statistics are available. The first 5 years

statistics for each standard were chosen to take into

account the differences of temporal horizon from

one standard to another. The first 5 years are

respectively and inclusively from 1993 to 1997 (ISO

9000), from 1999 to 2003 (ISO 14000), and from

2006 to 2010 (ISO 27000).

Source: Elaboration of the authors, based on ISO survey 2012 and

Enterprises Census from Statistics Canada and The Census Bureau of

Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB).

Figure 4: Percentage of Certificates Compared to

Registered Corporations in Canada and USA.

From figure 4 we can conclude that:

1). the diffusion of all the three generic standards

was low compared to the bulk of enterprises in

North America: after the first 5 years the rates of

diffusion are 0.36%, 0.06%, and 0.003%

respectively for ISO 9000, ISO 14000, and ISO

27000.

2). the IT security standard lags behind the

environment standard and far behind the quality

standard in terms of diffusion rate within

organizations in North America.

However, the above figures should be interpreted

with caution. Although ISO generic standards are

aimed at organizations of all sectors and all sizes,

one would argue that it would be an exaggeration to

assume that all registered enterprises are necessarily

potential adopters. Indeed, it has been empirically

demonstrated for example that the likelihood of ISO

9000 and ISO 14000 adoption increases with the

size of organizations, and that the early adopters are

mainly large firms (Bodas Freitas and Iizuka, 2012;

Pekovic, 2010). As for ISO 27000, its suitability for

SMEs has been questioned (Barlette et al., 2008).

However, SMEs cannot be ruled out completely

when it comes to standards adoption: in its efforts to

attract SMEs, ISO published certification guides

specifically targeting SMEs for all its generic

standards. Considering that the likelihood of ISO

certification is low for very small firms which

generally are under resources constraints (financial

and human) that put them at a disadvantage when it

comes to adopting and implementing standards

(Pekovic, 2010), it would make sense to analyze ISO

standards diffusion taking into account the size of

organizations. Unfortunately, such an analysis could

not be performed as ISO certification statistics do

not provide a breakdown by organization size.

It can also be argued that the differences between

the evolution statistics of the three generic standards

can be explained by the cumulative effects caused

by the lag time between their launch year and the

first year for which statistics are available. Indeed,

the launch years and the first years of available

statistics are respectively 1987 and 1993 for ISO

9000 (6-year lag), 1996 and 1999 for ISO 14000 (3-

year lag), 2005 and 2006 for ISO 27000 (1-year lag).

So, for ISO 9000, ISO 14000, and ISO 27000

statistics are available from respectively the 7th, 4th,

and 2nd years. While it would not be fair to compare

available statistics matching the years, given

differences of time horizon, one can compare the

three standards if, one counts at least 7 years

beginning at each launch time (and not at the first

year of statistics availability): in Figure 5 we see that

ISO 14000 had actually known the fastest growth

both worldwide and in North America, while ISO

27000 registered the slowest growth.

The faster growth of ISO 14000 compared to

ISO 9000 in their first years of adoption has been

attributed to factors related to the genesis of the two

standards, but the most important factor advanced is

that ISO 9000 success paved the way for ISO 14000

(Marimon, et al., 2011). One would then assume that

the diffusion of ISO 27000 would be facilitated by

both ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 series previous

implementations. The data contradict this

assumption: Figure 5 shows that initial growth for

ISO 27000 during the 7 first years was lower than

the initial growths for the two other generic

standards, both worldwide and in North America.

This can be explained in two main ways.

The first explanation can be found in statistics.

From statistics depicted in Figure 3, we can see that

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

12

ISO 27000 was launched at the moment when the

other generic standards were about to reach their

saturation level (worldwide) or were beginning to

decline (North America); the enthusiasm they had

originally attracted was beginning to fade, and the

brand new ISO series could not but suffer from such

a situation. The “de-institutionalization” of standards

that could be more or less associated with ISO

27000 is likely to negatively affect the later’s

diffusion across organizations.

The second explanation, rooted in institutional

theory as it refers to coercive isomorphism, is

probably the most significant. We illustrate it by the

following quote from one of our respondents, vice-

president of one of the certification bodies in North

America. When asked how he can explain the

differences between the statistics of certifications

between the generic standards, he responded:

“I think the reason is demand by the customers

of the certified organizations. Many business to

business purchasers were asking their suppliers

to be certified in ISO 9001 in the belief it would

make them more reliable suppliers. There was

less such demand with regard to ISO 14001. I am

not aware of any significant B2B demand for

ISO 27001”.

5 DISCUSSION

In accordance with the institutional theory, our study

contends that the low rate of ITSS diffusion across

organizations can be explained with reference to the

traditional institutionalization curve of innovations

(Lawrence et al., 2001). None of the available

international ITSS has yet reached the legitimation

phase of institutionalization whereby it would be

recognized as a largely agreed upon reference for

which most organizations would seek certification. It

seems that the bandwagon phenomenon

(Abrahamson and Rosenkopf, 1993) - that is the

diffusion of an innovation, regardless of its intrinsic

merits in terms of efficiency or returns, just because

the pressure to adopt it accumulates with the rising

number of organizations that have already adopted it

- does not yet apply for any of the available IT

security standards in general, and ISO 27000 in

particular.

We further contend that institutional theory

offers an appropriate theoretical framework to

analyze ITSS adoption by individual organizations.

The highly dynamic nature of IT infrastructure and

software industry entails a high level of ambiguity in

the assessment of ITSS efficiency or returns, and

therefore a certain degree of uncertainty for adopting

organizations. Yet, ambiguity surrounding an

innovation influences the bandwagon effect (Abra-

hamson and Rosenkopf, 1993): greater ambiguity

leads organizations to found their adoption decision

on social considerations as opposed to economic

efficiency. In case of uncertainty, organizations tend

to succumb to mimetic isomorphic pressures by

aligning themselves to standardized solutions or best

practices DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). With this in

mind, the low levels of ITSS certifications can be

interpreted as a reflection of the absence of one or a

few standard(s) whose adoption is generally

accepted as “best practice” to initiate the cycle of

mimetic isomorphism.

Alternatively, one would assume that we are still

in the early stages of ITSS diffusion in which

organizations (early adopters) are reluctant to adopt

the standards considering that the opaqueness about

their potential returns is unlikely to be compensated

by the magnitude of expected returns (Abrahamson

and Rosenkopf, 1993). These two explanations are

complementary and in line with institutional theory

according to which early adopters of an innovation

found their decision on technical analysis while later

adopters are mainly swayed by legitimacy pressures

(Lawrence et al., 2001).

Any institutional agent promoting an innovation

would like to see it diffused and legitimated at a fast

pace. He/she would also like to see it remaining

legitimate for a long period (stability). The

discipline-based mechanisms such as normalization

and examination on which certification bodies rely

for the diffusion of their IT security standards are

clearly not good enough for such a double purpose.

They are good for ensuring high stability, but

stability concerns come in only when an innovation

reaches the legitimation phase: as the pace of

institutionalization process with discipline-based

mechanisms is slow, the risks that the innovation

will never reach the legitimation phase are high. The

results of our analysis through the lens of

institutional theory show that the future of ITSS in

general, and ISO 27000 in particular, does not bode

well.

Force-based mechanisms would not either meet

the double requirement of fast pace and high

stability: they would ensure a fast pace of the

institutionalization process of ITSS, and fail to

guarantee its high stability. The fast growth of ISO

14000 as reported in the precedent section can be

explained by force-based mechanisms of

institutionalization such as environmental laws.

Such mechanisms need to be regularly activated

UnderstandingInformationTechnologySecurityStandardsDiffusion-AnInstitutionalPerspective

13

Source: Adapted from ISO Survey 2012.

Figure 5: ISO Certifications Numbers 7 Years after the Initial Launch.

(law enforcement) to maintain the commitment of

organizations (institutionalization stability). The

combined mechanisms (influence and discipline-

based mechanisms, and force and domination-

mechanisms) described by Lawrence et al. (2001)

seem to be the most appropriate for institutional

agents promoting the adoption of ITSS.

6 IMPLICATIONS AND

CONCLUSION

The literature review on ITSS shows discrepancies

between theory and practice. A consensus emerges

from both scholarly and professional publications

that ITSS are important and their implementation

necessary to help organizations deal with IT security

challenges in the information age. One would then

expect high levels of ITSS adoption in modern

organizations whose dependency on IT in almost all

their activities is tremendous. In reality, however,

few organizations have adopted the ITSS available.

As a result, many organizations are ill-prepared to

meet IT security challenges. We have shown that

institutional theory can be mobilized to understand

and explain this phenomenon and to devise

strategies that will not only prompt the diffusion

process (diffusion pace) of ITSS, but also ensure

their being embedded in routines and practices of

organizations for longer periods (stability).

From a theoretical point of view, this study

contributes to the theoretical foundation of research

in managerial IS/IT security, a research field that has

been thus far largely atheoretical (Björk, 2004).

From a practical point of view, considering the

diffusion of ITSS through the lens of institutional

theory may help any international, national, or

industrial entities engaged in or interested by

promoting IT security practices in organizations to

take appropriate measures. For instance, they would

consider adopting institutionalization mechanisms

that accelerate the diffusion pace of ITSS and ensure

a lasting commitment to those standards.

In line with institutional theory, we have arrived

at the conclusion that none of the available ITSS has

yet reached the legitimation phase that would make

it a taken-for-granted reference for any organization

seeking to implement sound IT security practices.

Arising from this result, an interesting research

avenue would be to explore how does an

organization deal with IT security challenges when

IT security standards that should serve as references

have not yet reached a stable institutional status.

In this study, the analysis of the evolution of one

of the major ITSS, namely ISO 27000, in

comparison with other generic standards from ISO

has provided interesting insights. However, the

consideration of other ITSS than ISO 27000 would

allow portraying a broader and more complete

picture of ITSS diffusion. We analyzed mainly ISO

statistics from North America, one of the regions

where the diffusion of ISO standards is the lowest. It

may be interesting to do the same analysis

contrasting regions with different patterns of

diffusion such as Europe and developing regions.

REFERENCES

Abrahamson, E., & Rosenkopf, L. 1993. Institutional and

competitive bandwagons: Using mathematical

modeling as a tool to explore innovation diffusion. The

Academy of Management Review, 18(3), 487-517.

Abu-Musa, A. A. 2002. Security of computerized

accounting information systems: An integrated

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

14

evaluation approach. Journal of American Academy of

Business, 2(1), 141-149.

Backhouse, J., Hsu, C. W., & Silva, L. 2006. Circuits of

power in creating de jure standards: Shaping an

international information systems security standard.

MIS Quarterly, 30(Special Issue), 413-438.

Barlette, Y., & Fomin, V. V. (2008, 7-10 January).

Exploring the suitability of IS security management

standards for SMEs. Paper presented at the 41st

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

(HICSS), Los Alamitos, Hawaii.

Björk, F. (2004). Institutional theory: A new perspective

for research into IS/IT security in organisations. Paper

presented at the 37th Hawaii International Conference

on System Sciences (HICSS), Big Island, Hawaii.

Bodas Freitas, I. M., & Iizuka, M. 2012. Openness to

international markets and the diffusion of standards

compliance in Latin America: A multi level analysis.

Research Policy, 41(1), 201-215.

Brooks, W. J., Warren, M. J., & Hutchinson, W. 2002. A

security evaluation criteria. Logistics Information

Management, 15(5/6), 377-384.

Caceres, G. H. R., & Teshigawara, Y. 2010. Security

guideline tool for home users based on international

standards. Information Management & Computer

Security, 18(2), 101-123.

Chang, E. S., Jain, A. K., Slade, D. M., & Tsao, S. L.

1999. Managing cyber security vulnerabilities in large

networks. Bell Labs Technical Journal, 4(4), 252-272.

Cousins, K. C., & Robey, D. 2005. The social shaping of

electroninc metals exchanges: An institutional theory

perspective. Information Technology & People, 18(3),

212-229.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. 1983. The iron cage re-

visited: Institutional isomorphism and collective

rationality in organizational fields. American

Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

Disterer, G. 2013. ISO/IEC 27000, 27001 and 27002 for

Information Security Management. Journal of

Information Security, 4(2), 92-100.

Enrione, A., Mazza, C., & Zerboni, F. 2006.

Institutionalizing codes of governance. American

Behavioral Scientist, 49(7), 961-973.

Fomin, V. V., de Vries, H. J., & Barlette, Y. (2008,

September 17-19). ISO/IEC 27001 information

systems security management standard: Exploring the

reasons for low adoption. Paper presented at the third

European Conference on Management of Technology

(EUROMOT), Nice, France.

Franceschini, F., Galetto, M., & Cecconi, P. 2006. A

worldwide analysis of ISO 9000 standard diffusion.

Considerations and future development.

Benchmarking: An International Journal, 13(4), 523-

541.

Franceschini, F., Galetto, M., & Gianni, G. 2004. A new

forecasting model for the diffusion of ISO 9000

standard certifications in European countries.

International Journal of Quality & Reliability

Management, 21(1), 32-50.

Gillies, A. 2011. Improving the quality of information

security management systems with ISO27000. TQM

Journal, 23(4), 367-376.

Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. 2002.

Theorizing change: The role of professional

associations in the transformation of institutionalized

fields. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58-80.

Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., & Boiral, O. 2013. Symbolic

adoption of ISO 9000 in small and medium-sized

enterprises: The role of internal contingencies.

International Small Business Journal, (Forthcoming),

1-22.

Hone, K., & Eloff, J. H. P. 2002. Information security

policy - What do international information security

standards say? Computers & Security, 21(5), 402-409.

Hu, Q., Xu, Z., Dinev, T., & Ling, H. 2011. Does

Deterrence Work in Reducing Information Security

Policy Abuse by Employees? Communications of the

ACM, 54(6), 54-60.

Lawrence, T. B., Winn, M. I., & Jennings, P. D. 2001. The

temporal dynamics of institutionalization. The

Academy of Management Review, 26(4), 624-644.

Marimon, F., Casadesús, M., & Heras, I. 2010.

Certification intensity level of the leading nations in

ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 standards. International

Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 27(9),

1002-1020.

Marimon, F., Llach, J., & Bernardo, M. 2011.

Comparative analysis of diffusion of the ISO 14001

standard by sector of activity. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 19(15), 1734-1744.

Orlowski, S. 1997. Government initiatives in information

technology security. Information Management &

Computer Security, 5(3), 111-118.

Pekovic, S. 2010. The determinants of ISO 9000

certification: A comparison of the manufacturing and

service sectors. Journal of Economics Issues, XLIV(4),

895-914.

Poore, R. S. 1999. Generally accepted system security

principles. Information Systems Security, Fall, 27-77.

PwC. (2013). Key findings from the 2013 US state of

cybercrime survey Retrieved from

https://www.pwc.com/en_US/us/increasing-it-

effectiveness/publications/assets/us-state-of-

cybercrime.pdf.

Sarker, S., & Lee, A. S. 2002. Using a positivist case

research methodology to test three competing theories-

in-use of business process redesign. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 2(Article 7), 1-

72.

Scott, W. R. 1987. The adolescence of institutional theory.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(4), 493-511.

Singleton, T. (2013). The top 5 cybercrimes. Retrieved

from http://www.aicpa.org/interestareas/forensicand

valuation/resources/electronicdataanalysis/downloadab

ledocuments/top-5-cybercrimes.pdf.

Siponen, M. 2006a. Information security standards focus

on the existence of process, not its content.

Communications of the ACM, 49(8), 97-100.

UnderstandingInformationTechnologySecurityStandardsDiffusion-AnInstitutionalPerspective

15

Siponen, M., & Willison, R. 2009. Information security

management standards: Problems and solutions.

Information & Management, 46(5), 267-270.

Siponen, M. T. 2006b. Secure-system design methods:

Evolution and future directions. IT Professional

Magazine, 8(3), 40-44.

Smith, S., Winchester, D., Bunker, D., & Jamieson, R.

2010. Circuits of power: A study of mandated

compliance to an information systems security de jure

standard in a government organization. MIS Quarterly,

34(3), 463-486.

Tejay, G. P. S., & Shoraka, B. 2011. Reducing cyber

harassment through de jure standards: a study on the

lack of the information security management standard

adoption in the USA. International Journal of

Management & Decision Making, 11(5-6), 324-343.

Tsohou, A., Kokolakis, S., Lambrinoudakis, C., &

Gritzalis, S. 2010. A security standards' framework to

facilitate best practices' awareness and conformity.

Information Management & Computer Security, 18(5),

350-365.

van Wessel, R., Yang, X., & de Vries, H. J. 2011.

Implementing international standards for Information

Security Management in China and Europe: A

comparative multi-case study. Technology Analysis &

Strategic Management, 23(8), 865-879.

von Solms, R. 1997. Driving safely on the information

superhighway. Information Management & Computer

Security, 5(1), 20-22.

von Solms, R. 1999. Information security management:

Why standards are important. Information

Management & Computer Security, 7(1), 50-57.

von Solms, S. H. 2005. Information security governance:

Compliance management vs operational management.

Computers & Security, 24(6), 443-447.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. 2002. Analyzing the past to

prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS

Quarterly, 26(2), xiii–xxiii.

Whitmore, J. J. 2001. A method for designing secure

solutions. IBM Systems Journal, 40(3), 747-768.

Wood, T., & Caldas, M. P. 2001. Reductionism and

complex thinking during ERP implementations.

Business Process Management Journal, 7(5), 387-393.

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

16