Comparing the Sensor Glove and Questionnaire as Measures of

Computer Anxiety

Tlholohelo S. Nkalai

1

, Lizette de Wet

1

and Robert Schall

2

1

Department of Computer Science and Informatics, University of the Free State, Nelson Mandela Drive,

Bloemfontein, South Africa

2

Department of Mathematical Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of the Free State, Nelson Mandela Drive,

Bloemfontein, South Africa

Keywords: Computer Anxiety, Skin Conductance, Physiological Measures, Usability Evaluation.

Abstract: Contradictory findings are reported in the literature concerning computer anxiety and how it affects the

performance of individuals executing computer-related tasks. The discrepancies in the findings could be

caused by the sole use of computer anxiety questionnaires. The aims of the present study were to establish

whether using a sensor glove provided complementary information to an existing computer anxiety

questionnaire; and to compare the computer anxiety of participants using a sensor glove and an anxiety

questionnaire with relation to performance. The study results suggest that the sensor glove and the anxiety

questionnaire provided different information concerning participants’ anxiety before and after performing

tasks on the computer. A negative correlation between computer anxiety and performance was found using

both the sensor glove measurements and the computer anxiety scores. It is concluded that the sensor glove

possibly measures a different variable from the anxiety questionnaire and further research is necessary in

that regard. Additionally, it is concluded that the higher an individual’s levels of anxiety, the poorer he/she

performed on the assessment.

1 INTRODUCTION

Computer anxiety is defined as an emotional fear or

phobia experienced by individuals when using

computers or when thinking of using computers

(Chua et al., 1999). According to Blignaut, Burger,

McDonald and Tolmie (2005, p.500) it is “a diffuse,

unpleasant, and vague sense of discomfort and

apprehension when confronted by computer

technology or people who talk about computers”.

Concerning these definitions of computer anxiety, it

is evident that computer anxiety involves emotional

“fear” or “apprehension” when interacting or

anticipating interaction with computers.

1.1 Computer Anxiety and Stress

Researchers agree that individuals experiencing

computer anxiety exhibit certain physiological

reactions. These reactions may include sweaty

palms, dizziness or light headedness, rapid

breathing, a pounding heart, feelings of unreality,

chest pain, shaking or trembling (Appelbaum and

Primer, 1990; Beckers and Schmidt, 2001; Mayo

Clinic, 2012). Some of these physiological reactions

are similar to those of individuals experiencing

stress. According to Rogge (2011), the symptoms of

stress include pain in the abdomen, headaches and

muscle tightness or pain. For highly stressed

individuals, the symptoms may include a faster heart

rate, skipped heartbeats, rapid breathing, sweating,

trembling and dizziness. It is apparent that, based on

these symptoms of anxiety and stress, it is easy to

misinterpret anxiety for stress or vice versa. To

distinguish between the two, Merrill (2013) states

that stress is instigated by an existing stress-causing

factor or “stressor”, whereas anxiety is stress that

remains after the “stressor” is gone. Despite this

distinction, anxiety and stress are sometimes used

interchangeably with the understanding that they

have a similar meaning (Princeton University,

2013). In this paper we also use the terms anxiety

and stress interchangeably.

93

Nkalai T., de Wet L. and Schall R..

Comparing the Sensor Glove and Questionnaire as Measures of Computer Anxiety.

DOI: 10.5220/0005229800930103

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems (PhyCS-2015), pages 93-103

ISBN: 978-989-758-085-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

1.2 Computer Anxiety and

Performance

Individuals experiencing computer anxiety tend to

score poorly in tests which require them to use

computers (Glaister, 2007; Parayitam et al., 2010).

In the study conducted by Glaister (2007), the

student nurses who reported having medium to high

anxiety levels performed poorer than those with low

levels of computer anxiety. According to Parayitam

et al., (2010), students experiencing computer

anxiety obtain low grades as a consequence of

avoiding assignments or exercises which necessitate

them to use computers. Despite these findings, a

recent study conducted by Olufemi and Oluwatayo

(2014) revealed a non-significant difference in the

performance of students with high, moderate and

low computer anxiety. The performance was based

on the scores obtained by the students in a computer-

based test.

Since reports in the literature disagree about how

computer anxiety affects performance of individuals,

extensive investigations regarding computer anxiety

and performance are necessary.

1.3 Computer Anxiety Questionnaires

In many research studies concerning computer

anxiety, computer anxiety questionnaires have been

used as the sole instruments for measuring anxiety.

Examples include studies conducted by Aziz and

Hassan (2012), Hismanoğlu (2011), Korobili, Togia

and Malliari (2010), Longe and Uzoma (2007), and

Ursavas and Teo (2011). According to Isen and Erez

(2006), the exclusive use of questionnaires is

insufficient for drawing conclusions about emotions.

This is because of the limitations posed by this

method. For example, the participants may

experience ambiguous emotions which can be

difficult to interpret accurately. Moreover, factors

such as incentives or even rules can influence the

participants to respond the way they think is

appropriate or expected by the researcher (Bandura,

1971 cited in Isen and Erez, 2006). Other possible

measurements are therefore worth investigating.

1.4 Physiological Measures

Physiological measures are defined as physical

signals of the human body which are produced when

the body undergoes psychological changes. These

measures are also termed psychophysiological

measures where the preceding word “psycho”

emphasizes that a measurement is taken of the

psychological state of an individual (Dirican and

Göktürk, 2011).

Employing physiological measures is

advantageous in that the measurements are objective

−they do not depend on the views of the participants

(unlike questionnaires). Physiological measures are

also unobtrusive in that they do not interfere with the

participant’s natural behavior. Moreover, the signals

can be measured in real-time because they are

continuous (Kivikangas et al., 2011).

Special equipment is required to measure

physiological signals. Examples of the equipment

include the BodyMedia SenseWear armband

(SwordMedical, 2010), Galvactivator (Picard and

Scheirer, 2001), and the Emotion RECognition

sensor system (EREC) (Kaiser and Oertel, 2006).

Physiological measures are employed in a research

area named affective computing. The goal behind

affective computing is to provide computers with

emotional intelligence and make them understand

emotions in a similar way as a human being would

do (Picard, 1997).

From the above-mentioned definition of

computer anxiety by Chua et al., (1999), which is in

agreement with Cambre and Cook (1987), computer

anxiety is specified as an emotional state. As a

result, it can be inferred that computer anxiety is an

emotion. Since emotions have successfully been

investigated using physiological measures in

affective computing, it was deemed appropriate that

computer anxiety be investigated using these

measures.

The physiological measure employed in the

present study was skin conductance. When an

individual experiences increased sympathetic

activation, for example, in cases of stress and

nervous tension, the individual’s palms become

damp because increased sympathetic activity causes

the sweat ducts and the surface of the skin to be

hydrated. This hydration (sweating) causes the skin

resistance to decrease while the conductance will

increase (Barreto, 2008).

When describing changes in electrical

conductance of the skin, the term generally used is

EDA rather than skin conductance. EDA is

reflective of the changes in autonomic sympathetic

arousal associated with emotional and cognitive

states (Critchley, 2002). It is among the signals that

are used in polygraph (‘lie-detector’) tests and in

studies that involve stress and cognitive workload

(Picard and Scheirer, 2001). EDA is considered to

be very sensitive to physiological changes (Barreto,

2008).

It is difficult to determine the cause of a certain

change in skin conductance as it can be triggered by

PhyCS2015-2ndInternationalConferenceonPhysiologicalComputingSystems

94

various stimuli. However, the skin conductance level

swiftly elevates in events which are major or of

intense nature (for example when experiencing

stress and anxiety). When executing tasks that

involve mental workload, the level is inclined to

increase suddenly and then decrease slowly.

Normally this response occurs at the beginning of

new and engaging experiences (Picard and Scheirer,

2001).

1.5 Purpose of the Study and

Hypotheses

Traditionally, computer anxiety has been

investigated using computer anxiety questionnaires

solely. The goals of the present study were to: (1)

establish whether using a sensor glove provided

complementary knowledge to an existing computer

anxiety questionnaire; (2) compare the computer

anxiety of participants using a sensor glove and an

anxiety questionnaire with relation to performance.

The following statistical null hypotheses were

tested:

H1: There is no correlation between existing

computer anxiety questionnaire scores and

conductance readings of the sensor glove before and

after interaction with a computer.

H2: There is no correlation between computer

anxiety and performance according to computer

anxiety questionnaire scores and skin conductance

readings.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit 58

participants for the study. The participants were

computer illiterate individuals who had recently

been enrolled in a partnership programme at a local

university. In this programme, the participants

received free computer literacy training for one

week. The participants were recruited for this study

after completing the programme. The participants

had basic education (with Matric or Grade 12 as the

highest qualification) and the majority of them did

not have access to computers at home. Because of

their background, it was expected that the

participants would exhibit anxiety when working

with computers. An informed consent form was

issued to each participant before the data collection

commenced.

2.2 Measures

As mentioned earlier, data were gathered using an

existing computer anxiety questionnaire and an

instrument for measuring physiological data.

Additional methods for collecting data were pre-test

and post-test self-developed questionnaires,

observations and interviews.

2.2.1 Computer Anxiety Rating Scale

The questionnaire instrument used in the present

study was the Computer Anxiety Rating Scale

(CARS), developed by Heinssen, Glass and Knight

(1987). CARS consists of 19 items with a five-point

Lickert type scale rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to

5 (strongly agree). The CARS scores range from 19

to 95 where the higher scores reflect higher levels of

computer anxiety (Heinssen et al., 1987). The CARS

questionnaire was completed by each participant

before and after executing tasks on the computer.

The aim was to measure and compare the levels of

computer anxiety of the participants at these two

instances.

2.2.2 Emotion RECognition System

The physiological measuring instrument used in the

study was the Emotion RECognition system (EREC

II) sensor glove. According to Kaiser and Oertel

(2006), the EREC system was developed in

Germany at the Fraunhofer Institute for Computer

Graphics Rostock (IGD-R).

The two main parts of the EREC system are the

sensor unit and the base unit. The sensor unit, in the

form of a glove, contains the skin resistance and skin

temperature sensing elements. Additionally, the

sensor unit measures the environmental air

temperature. The sensing elements are integrated in

the glove, but the sensor circuitry is placed in a

small wrist pocket (Peter et al., 2007). The

components of the EREC II are shown in Figure 1.

Although EREC can be used to measure skin

temperature, skin resistance and heart rate, in this

study the researchers were particularly interested in

skin conductance which was calculated from the

skin resistance measurements. Skin resistance is

measured in Kilo-ohms (kΩ) which was converted

into conductance in milli-Siemens (mS).

Conductivity is the reciprocal of resistivity, therefore

the conversion was performed easily. The EREC

system captured ten skin resistance readings per

second and the data were recorded in a Microsoft

(MS) Excel application.

ComparingtheSensorGloveandQuestionnaireasMeasuresofComputerAnxiety

95

Figure 1: EREC II components (Picture taken in the

usability lab at the research institution.).

2.2.3 Pre-test and Post-test Questionnaires

The pre-test questionnaire was used for capturing

demographic data, for example age and gender. The

post-test questionnaire was used to record the

subjective emotions (anxiety and/or stress)

experienced by the participants during the different

stages of data gathering. The participants indicated

which among the allocated nine tasks caused them to

experience the two emotions. They also provided

their perceived reasons for experiencing those

emotions. Furthermore, the participants were

required to rate their experiences with the glove in

terms of comfort and time taken to set it up.

2.2.4 Observations

Each participant performed tasks on the computer in

a usability lab. The recordings were taken according

to a pre- designed schedule using pen and paper.

Recordings of time-on-task and task success were

noted. Time-on-task allowed the researchers to

assess the various task durations. The task success

rate (percentage of the tasks completed successfully)

enabled the researchers to evaluate the performance

of the participants by task. The tasks that were not

completed in the given amount of time were also

noted. Also of importance were the overt behaviours

of the participants, such as body language, words

uttered, and facial expressions.

2.2.5 Interviews

Interviews were conducted after the participant had

completed the questionnaires to ensure that the

researchers understood what was written in the

questionnaire, as some responses to the questions

were not legible or written in improper English.

2.3 Procedure

The data was collected in the usability lab of a local

university. The usability lab offered a suitable

environment for the use of the testing instruments,

with one participant at a time performing tasks on a

computer.

The participant wore the EREC sensor glove and

completed the pre-test and CARS questionnaires

before executing tasks using the MS Word

application. The tasks were presented in a small

moveable application window which was designed

in such a way that only one task was displayed at a

time. A “next” button appeared on the application

window that allowed the participant to display the

subsequent task. While the tasks were presented in

the application window, the MS Word application

was opened simultaneously on the screen behind the

application window containing the tasks.

Consequently, the participant was able to view the

task to be performed as well as the MS Word

application where the execution of tasks was

performed. The participant was assigned three

minutes for each task.

After executing all the tasks, the participant was

required to complete the post-test questionnaire, and

once again the CARS questionnaire. An interview

was conducted with the participant to clarify

responses to the questionnaires.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

Data were gathered from 58 participants of whom 25

were males and 33 females. The participants’ ages

ranged from 16 to over 40 years. The largest

proportion of participants (36.2%) was in the age

group of 21 to 25 years, whereas only 3.4% of

participants were older than 40 years. The largest

group of the participants (70.7%) spoke Sotho or

Tswana as their home language, followed by Xhosa

(25.9%). Only one participant each (1.7%) spoke

Afrikaans and Zulu as their home language. With

regard to educational background, 47 (81%) of the

participants had completed Matric, whereas 11

(19%) had not.

3.2 Hypothesis Testing

The participants were required to complete the

CARS questionnaire before and after performing the

tasks on the computer. The CARS scores (pre and

PhyCS2015-2ndInternationalConferenceonPhysiologicalComputingSystems

96

post assessment) were compared with the skin

conductance readings of the EREC sensor glove

before and after the assessment. The comparisons

were made to address the first hypothesis stated as:

H1: There is no correlation between existing

computer anxiety questionnaire scores and

conductance readings of the sensor glove before and

after interaction with a computer.

The aim of the comparison was to establish whether

the results provided similar or different information

regarding levels of anxiety before and after the

assessment (interaction with the computer). The

existing computer anxiety questionnaire used was

the CARS. A correlation test was performed in the

following instances to investigate the following:

3.2.1 Anxiety before Assessment

3.2.1.1 The Correlation between Total Scores on

the CARS Pre-test Questionnaire and the

Average Skin Conductance Readings during the

First Minute of Wearing the Glove

Results:

There was no significant correlation (r = 0.144, p >

0.05) between the pre-test questionnaire score and

the average skin conductance reading for the first

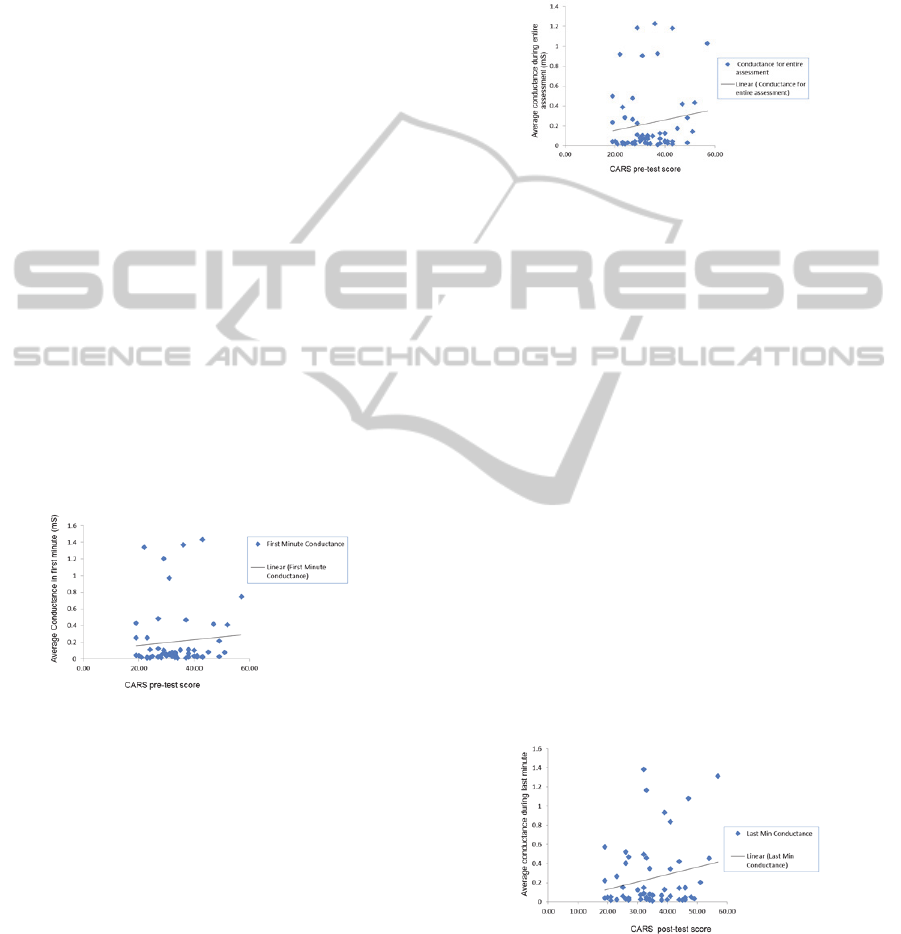

minute (see Figure 2 for the scatterplot).

Figure 2: Average conductance in first minute as a

function of CARS pre-test score.

Finding:

From this result we can conclude that the sensor

glove (first minute) and the CARS pre-test

questionnaire potentially provide different

information regarding levels of anxiety before the

assessment.

3.2.1.2 The Correlation between Total Scores on

the CARS Pre-test Questionnaire and the

Average Skin Conductance Reading on the

Sensor Glove during the Entire Assessment

This correlation was calculated to investigate

whether the result found in 3.2.1.1 was caused by

inaccurate reading of anxiety during the first minute.

Results:

There was no significant correlation (r = 0.168; p >

0.05) between the total scores on the CARS pre-test

questionnaire and the average skin conductance

reading on the sensor glove during the entire

assessment (see Figure 3 for the scatterplot).

Figure 3: Average conductance during entire assessment

as a function of CARS pre-test score.

Finding:

This result confirms the conclusion made in 3.2.1.1.

The sensor glove and the CARS pre-test

questionnaire potentially provide different

information regarding levels of anxiety before the

assessment.

3.2.2 Anxiety after Assessment

3.2.2.1 The Correlation between Total Scores on

the CARS Post-test Questionnaire and the

Average Skin Conductance Readings during the

Last Minute of Wearing the Glove Was

Calculated

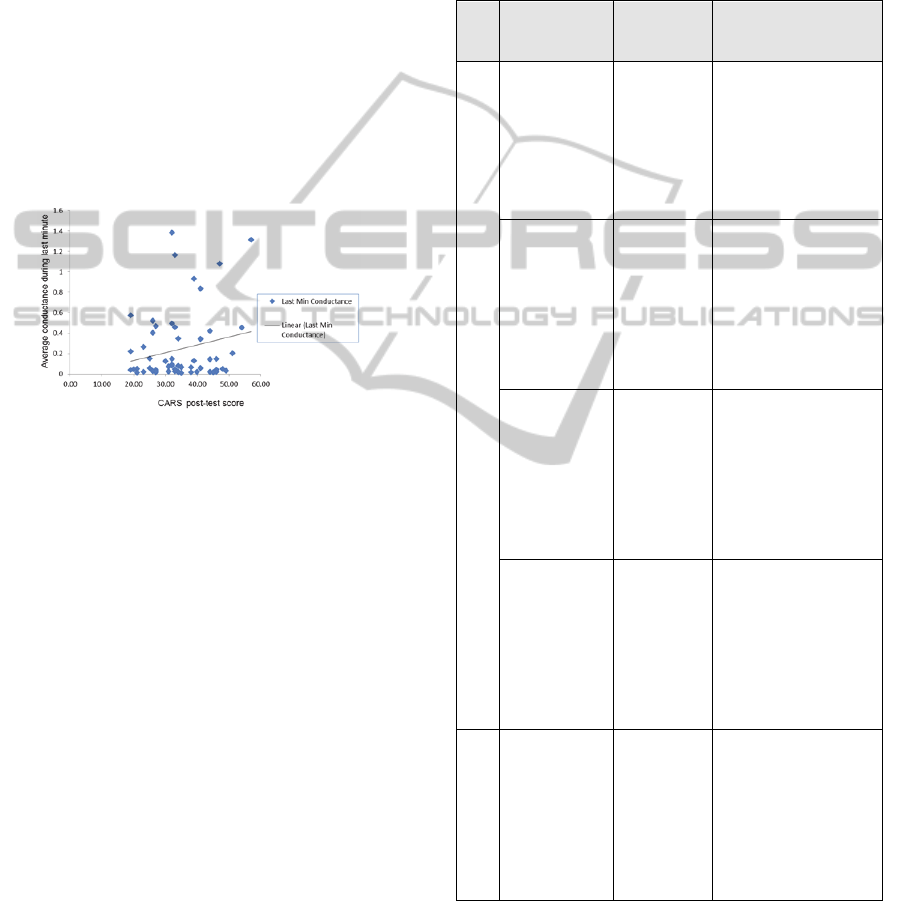

Results:

There was no significant correlation (r = 0.192; p >

0.05) between the total scores on the CARS post-test

questionnaire and the average readings during the

last minute of wearing the glove (see Figure 4 for

the scatterplot).

Figure 4: Average conductance during the last minute as a

function of CARS post-test score.

Finding:

From this we can conclude that the sensor glove (last

minute) and the CARS post-test questionnaire

potentially provide different information regarding

ComparingtheSensorGloveandQuestionnaireasMeasuresofComputerAnxiety

97

levels of anxiety after the assessment.

3.2.2.2 The Correlation between Total Scores on

the CARS Post-test Questionnaire and the

Average Skin Conductance Readings on the

Glove during the Entire Assessment was

Calculated

This correlation was calculated to investigate

whether the result found in 3.2.2.1 was caused by

inaccurate reading of anxiety during the last minute.

Results:

There was no significant correlation (r = 0.229; p >

0.05) between the total scores on the CARS post-test

questionnaire and the average readings of the glove

during the entire assessment (see Figure 5 for the

scatterplot).

Figure 5: Average conductance during entire assessment

as a function of CARS post-test score.

Finding:

This result confirms the conclusion made in 3.2.2.1.

The sensor glove and the CARS post-test

questionnaire potentially provide different

information regarding levels of anxiety after the

assessment.

In order to confirm the finding that the sensor

glove and the CARS questionnaire potentially

provide different information regarding levels of

anxiety, another statistical test, Multivariate

Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was conducted to

confirm the findings that were established from

using the correlation test.

Participants were divided into three categories:

those with high anxiety scores, those with medium

anxiety scores, and those with low anxiety scores, all

according to the skin conductance readings of the

sensor glove. The CARS pre-test scores and the

CARS post-test scores were then compared among

these three groups.

i. If the glove and the CARS questionnaires

provide the same information, we would expect

that there would be differences in the self-

reported anxiety scores between these three

groups.

ii. If the glove and the CARS questionnaires

provide different information, we would expect

that there would be no differences in the self-

reported anxiety scores between these three

groups.

Table 1: Summary of findings regarding anxiety before

and after assessment.

Stat.

Test

Variables Result Finding

CORRELATION

CARS pre-test

total score,

average skin

conductance

reading in first

minute

No significant

correlation

(r = 0.144;

p > 0.05)

Sensor glove (first

minute) and CARS

pre- test questionnaire

potentially provide

different information

about levels of anxiety

before the assessment.

CARS pre-test

total score,

average skin

conductance

reading for the

entire

assessment

No significant

correlation

(r = 0.168;

p > 0.05)

Sensor glove and CARS

pre-test questionnaire

potentially provide

different information

regarding levels of

anxiety before the

assessment.

CARS post-test

total score,

average skin

conductance

reading in last

minute

No significant

correlation

(r = 0.192;

p > 0.05)

Sensor glove (last minute)

and CARS

post- test questionnaire

potentially provide

different information

regarding levels of

anxiety after the

assessment.

CARS post-test

total score,

average skin

conductance

readings for

entire

assessment

No significant

correlation

(r = 0.229;

p > 0.05)

Sensor glove and CARS

post-test questionnaire

potentially provide

different information

regarding levels of

anxiety after the

assessment.

MANOVA

CARS pre-test

scores, CARS

post-test scores

(among 3 groups

of different

anxiety levels

according to

sensor glove)

No significant

differences

(F = 0.798;

p > 0.05)

Confirms that sensor

glove and CARS

questionnaire potentially

provide different

information regarding

levels of anxiety.

Results:

No significant differences (F = 0.798; p > 0.05) were

found in the self-reported anxiety scores (for the pre-

test and the post-test) between these three groups.

Finding:

This result confirms that the sensor glove and the

PhyCS2015-2ndInternationalConferenceonPhysiologicalComputingSystems

98

CARS questionnaire potentially provide different

information regarding levels of anxiety.

A summary of the statistical tests concerning the

anxiety according to the sensor glove and the CARS

questionnaire is presented in Table 1.

From these results the first hypothesis, H1 cannot

be rejected, since p > 0.05. Although statistical tests

showed no significant correlations between CARS

scores and the glove readings, the scatterplots reflect

the small positive correlation between conductance

measurements and CARS scores; possibly those

correlations are small (and not statistically

significant) because of much noise in the data. Note

the scatterplots show the conductance measurements

to be close to zero (below 0.2) for most subjects.

However, for about 18 other subjects the

conductance measurements are very variable, some

values are up to about 1.2. Moreover, the researchers

encountered a challenge of non-continuous

measurements of skin conductance. With some

participants the EREC glove momentarily stopped

recording the skin conductance because the sensors

of the glove were no longer in contact with the skin

despite the Velcro straps that were used to tighten

the sensors to the skin. This could have caused noise

in the data.

The second hypothesis was stated as:

H2: There is no relationship between computer

anxiety and performance as measured by a sensor

glove and a computer anxiety questionnaire.

This hypothesis was addressed by performing

correlations between the CARS scores and

performance scores, and the skin conductance

readings with performance scores. Performance was

measured as the percentage of tasks which were

completed successfully/correctly by each participant.

Table 2: Summary of findings regarding anxiety and

performance.

Stat.

test

Variables Result Finding

CORRELATION

CARS pre-test

score,

performance

score

Significant negative

correlation

(r = -0.331; p <

0.05)

The higher the

levels of anxiety,

the poorer the

performance on

the assessment.

CARS post-test

score,

performance

score

Significant negative

correlation

(r = -0.332; p <

0.05)

Average skin

conductance

readings during

the entire

assessment,

performance

score

Significant negative

correlation

(r = -0.300; p <

0.05)

In order to determine whether there is a

relationship between anxiety and performance, the

analyses shown in Table 2 were performed.

Considering the results in Table 2, the second

hypothesis, H2 can be rejected at p < 0.05 in all the

related tests.

3.3 Observations

When the participants performed the nine tasks on

the computer, two measurements were recorded,

namely the time-on-task and the task success rate.

Moreover, the behaviours which were exhibited by

the participants when performing the tasks were

observed and recorded. The three types of

recordings are presented in the subsequent sections.

3.3.1 Time-on-Task and Task Success

A maximum of three minutes was allocated to each

of the nine tasks that a participant was required to

perform in a word processor application. Time-on-

task was recorded for each task and when three

minutes had elapsed the participant was asked to

stop and continue with the next task, even if the

current task was incomplete. Table 3 depicts the

time-on-task and task success rate for each of the

nine tasks.

From Table 3, it can be seen that the last task

“Save” was performed in the longest time (average =

2 min, 41s) while the task “Bold” (average = 37s)

took the shortest time to complete.

Table 3: Average, minimum and maximum durations of

tasks.

Tasks Time-on-task

Task success

(%)

Average

time-on-task

(mm:ss)

Minimum

time-on-task

(mm:ss)

Maximum

time-on-task

(mm:ss)

Center 1:13 0:08 3:00 84.2

Change to

italic

0:49 0:06 3:00 84.2

Change line

spacing

2:01 0:15 3:00 43.9

Cut & Paste 2:16 0:38 3:00 43.9

Change font

size

0:39 0:06 3:00 84.2

Bold 0:37 0:06 3:00 93.0

Underline 0:56 0:13 3:00 89.5

Bullet 1:37 0:25 3:00 77.2

Save 2:41 0:29 3:00 10.2

Table 3 also depicts the task success rate. The

ComparingtheSensorGloveandQuestionnaireasMeasuresofComputerAnxiety

99

task success rate according to each of the nine tasks

shows the percentage of participants who completed

successfully/correctly each of the tasks. In

agreement with the time-on-task, the task success

rate shows that the task “Save” had the lowest task

success rate (10.2%) while the task “Bold” had the

highest rate (93.0%). This means that the majority of

participants failed to complete the task “Save”

successfully, but executed the task of “Bold”

successfully. Considering both time-on-task and

task-success, it can be seen that the task that most

participants failed to execute successfully was the

task that required the longest time to perform.

3.3.2 Observed Behaviours

As mentioned earlier, the participants were observed

as they were executing the tasks. Some behaviours

exhibited by the participants who were failing or

struggling to perform the tasks were: fidgeting in the

chair, tapping fingers on the table, moving closer

and away from the monitor, exclaiming in

bewilderment or disappointment, sighing, shaking

head in denial, constant blinking of eyes, trembling

hands, uttering words (for example, words that

pleaded with computer to do something), staring at

the monitor, and holding the face with two hands

with elbows on table. It was noted that among the

tasks that were performed, almost all the participants

struggled with the last task, which was to save the

document in a specified location. When they had to

complete this task, most participants exhibited some

of the above-mentioned behaviours. However, these

behaviours were also noticed when participants

performed a few of the earlier tasks.

3.4 Findings from Questionnaire Data

The following are the findings made from the data

collected from the pre-test and post- test

questionnaires where different themes were

discovered.

3.4.1 EREC Sensor Glove

Most of the participants described the glove using

phrases such as “interesting” and “comfortable.”

They stated that the glove did not disturb or distract

them when performing the tasks on the computer,

although they were “conscious” that they were

wearing it.

3.4.2 Participants’ Reported Emotions

The participants felt excited, afraid, neutral and

frustrated while using the computer. However, the

majority felt excited when they thought of using a

computer, while they were using it, and even after

using it.

Regarding the tasks which they performed, the

majority of the participants described that they were

stressed rather than anxious or afraid. Most

participants were stressed by the last task, “Save.”

The reasons that participants provided for being

stressed and/or anxious were classified into eight

categories namely: lack of knowledge on how to

perform the task; difficulty in performing the task;

consciousness of time; exercised caution to avoid

mistakes; uncertainty of whether a task was

performed correctly; lack of remembrance; first

time experience; and lack of confidence to execute

the task correctly.

4 DISCUSSION

The following discussion is based on the results

regarding the sensor glove, the reported emotions

experienced by the participants, the observations and

the statistical findings.

4.1 EREC Sensor Glove

Since most participants found the glove to be

“interesting” and “comfortable”, and not disturbing

nor distracting, it can be concluded that the sensor

glove, as a measuring tool, is suitable in terms of

comfort and can therefore be recommended for other

studies. Nonetheless, the size of the sensor glove in

relation to the size of the participants’ hands should

be carefully considered. In this study, the glove was

found to be too small for some hands and in some

cases the wires were disconnected as a consequence

of the glove being stretched. In such instances of

discontinuous data, the data was discarded in order

to use valid data only.

4.2 Emotions

As stated earlier, the participants reported having

experienced various emotions, which included

excitement, anxiety (or fear) and frustration, while

using the computer. It can be expected that the

participants were excited and anxious

simultaneously because experiencing something

interesting for the first time can be exciting. At the

same time one can be somewhat afraid of the

unknown. The feeling of frustration can also be

expected when one fails to execute tasks, especially

PhyCS2015-2ndInternationalConferenceonPhysiologicalComputingSystems

100

when one “was careful not to do mistakes” or felt

that “time was running out and I was not doing it”,

as some of the participants reported. It is most likely

that participants experienced frustration which led to

stress as they were performing the last task which

most participants failed to complete.

4.3 Findings from Observations and

Questionnaires

Considering the results from the observations, it is

apparent that the last task caused the participants

anxiety or stress. The participants took the longest

time to perform it and struggled the most to execute

it (see Section 3.3.1). Moreover, the participants

reported that they felt stressed when performing it

(see Section 3.4.2). Moreover, most of the

behaviours which were exhibited by the struggling

participants (see Section 3.3.2) were observed when

the last task was executed. These behaviours

exhibited by the participants who were failing or

struggling to perform tasks (for example, sighing,

shaking head in denial, and constant blinking of the

eyes) were observed, as mentioned in Section 3.3.2

The behaviours (for example, trembling) were

mentioned in literature (Mayo Clinic, 2012; Rogge,

2011) as behaviours common to individuals

experiencing computer anxiety or stress. It was

therefore evident that at some point the participants

experienced anxiety, taking into consideration that

stress and anxiety are difficult to differentiate as

mentioned in Section 1.1.

4.4 Computer Anxiety and

Performance

Statistically significant negative correlations were

found between anxiety and performance, suggesting

that a relationship between performance and anxiety

probably exist; the higher a person’s levels of

anxiety, the poorer he/she performed on the

assessment. Since this relationship was found from

the results of both the CARS questionnaire and the

sensor glove, we conclude that computer anxiety

possibly has an effect on the performance of the

users performing tasks on the computer.

4.5 Reviewing the Goals of the Study

The first goal of this study was to establish whether

using a sensor glove provided complementary

knowledge to an existing computer anxiety

questionnaire. No significant correlations were

found between the measurements of anxiety using

respectively the sensor glove and the CARS

questionnaire (see Table 1). One possible

interpretation of this finding is that the sensor glove

does not measure the same variable as the CARS

anxiety questionnaire, and thus potentially provides

different information on anxiety than the CARS

questionnaire. Of course, the absence of significant

correlations would also be explained by either one of

the instruments, or both, not being suitable measures

of anxiety. However, both measurements were

significantly correlated with performance, which

suggests that both instruments return a signal, and

not just noise. The CARS questionnaire has been

validated as a measurement of anxiety whereas the

sensor glove has not been validated for that specific

measurement. The sensor glove measures skin

conductance or GSR which, according to literature

(Lin and Hu, 2005; Picard, 1997), has been used

successfully to measure stress. What remains to be

investigated is the relationship (or a distinction)

between computer anxiety and stress because it is

evident that anxiety and stress, though different, are

closely related.

The second goal of this study was to relate

computer anxiety of participants, as measured by a

sensor glove and an anxiety questionnaire,

respectively, to performance. Our findings suggest

that a relationship between anxiety and performance

probably exists, namely the higher an individual’s

levels of anxiety, the poorer he/she performed on the

assessment. This finding was also reported by

Glaister (2007) and Parayitam et al., (2010), but

contradicts the finding of Olufemi and Oluwatayo

(2014) who found no significant differences in

performance scores in subjects with high, moderate

and low computer anxiety. Again we can note that it

is difficult to distinguish between stress and anxiety.

The task that the participants failed to complete was

the one reported to cause the highest stress. In effect,

the majority of the participants indicated that they

experienced stress rather than anxiety as they were

performing the tasks.

4.6 Recommendations for Further

Research

The present study that investigated computer anxiety

using physiological measures is amongst the first of

its nature in a third world country.

Recommendations for further research are therefore

presented. Firstly, skin conductance readings of one

minute before and after interaction with the

computer may not have been optimal. This design

could have influenced the correlation between the

ComparingtheSensorGloveandQuestionnaireasMeasuresofComputerAnxiety

101

sensor glove and the CARS. No literature references

have been found on the optimal duration for reading

conductance. It is suggested that a research study be

conducted to establish the optimal timing of

conductance measurements using the sensor glove.

Secondly, it is noted that the measurements using

the sensor glove and the anxiety questionnaire,

respectively, had similar correlations with

performance, yet the two types of measurements of

anxiety were not significantly correlated. These

findings call for deeper investigation of objective

and subjective measures of computer anxiety in the

context of third world countries.

Thirdly, the participants were directly observed

while performing tasks in this study. Since the

participants were aware that they were being

observed, there is a possibility that the

measurements could have been influenced by this

awareness. Perhaps a study conducted with

participants who are oblivious of being watched

would produce different results.

Fourthly, since the start of this study, improved

versions of the sensor glove have appeared on the

market. Furthermore, the glove used in the present

study was small and volatile. Using the improved

version of the glove in similar investigations might

provide interesting results.

Fifthly, a study which includes another

instrument, such as a heart rate monitor could give

more understanding about computer anxiety. In this

study heart rate was not measured because the heart

rate monitor packaged in the EREC malfunctioned

and due to time constraints it could not be fixed.

The final recommendation for follow-up studies

is to establish the relationship between anxiety and

stress. Perhaps a study could be conducted where

both anxiety and stress questionnaires are employed.

The data from the two questionnaires could be

related to conductance data from the sensor glove.

The findings of such a study could provide more

insight about anxiety and stress when interacting

with a computer. A study that utilised a stress

questionnaire and conductance data (Lin and Hu,

2005) has already been performed. However, in that

study an anxiety questionnaire was not included.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated computer anxiety using

subjective (scores from an anxiety questionnaire)

and objective (conductance data from the sensor

glove) measures. The correlations between apparent

computer anxiety and performance were similar

using the two measures of anxiety. The study

findings confirmed the literature where it has been

stated that the higher the anxiety levels of an

individual, the poorer they are likely to perform.

Additionally, this study is amongst the first research

studies conducted in a third world country where

computer anxiety was measured using an objective

physiological instrument.

REFERENCES

Appelbaum, S. H. and Primer, B., 1990. An HRx for

computer anxiety. Personnel, 67(9), pp.8-11.

Aziz, S. and Hassan, H., 2012. A study of computer

anxiety of higher secondary students in Punjab.

International Journal of Social Sciences & Education,

2(2), pp.264-273.

Barreto, A., 2008. Non-intrusive physiological monitoring

for affective sensing of computer users. New

Developments, 85, pp.85-100.

Beckers, J. J. and Schmidt, H. G., 2001. The structure of

computer anxiety: A six-factor model. Computers in

Human Behavior, 17, pp.35-49.

Beckers, J. J. and Schmidt, H. G., 2003. Computer

experience and computer anxiety. Computers in

Human Behavior, 19, 785-797.

Beckers, J. J., Rikers, R. M. and Schmidt, H. G., 2006.

The influence of computer anxiety on experienced

computer users while performing complex computer

tasks. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(3), pp.456-

466.

Beckers, J. J., Wicherts, J. M. and Schmidt, H. G. (2007).

Computer anxiety: “Trait” or “state”? Computers in

Human Behavior, 23, pp.2851-2862.

Blignaut, P., Burger, A., McDonald, T. and Tolmie, J.,

2005. Computer attitude and anxiety. In M. Khosrow-

Pour, ed. Encyclopedia of Information Science and

Technology. Hershey: Idea Group Publishing. pp.495-

501.

Cambre, M. A. and Cook, D. L., 1987. Measurement and

remediation of computer anxiety. Educational

Technology, 27 (12), pp.15-20.

Chua, S. L., Chen, D. and Wong, A. F. L., 1999.

Computer anxiety and its correlates: A meta-analysis.

Computers in Human Behavior, 15, pp.609-623.

Critchley, H. D., 2002. Book review: Electrodermal

responses: What happens in the brain? Neuroscientist,

8(2), pp.132-142.

Dirican, A. C. and Göktürk, M. 2011. Psychophysiological

measures of human cognitive states applied in human

computer interaction. Procedia Computer Science, 3,

pp.1361-1367.

Glaister, K., 2007. The presence of mathematics and

computer anxiety in nursing students and their effects

on medication dosage calculations. Nurse Education

Today, 27(4), pp.341-347.

Heinssen, R. K. J., Glass, C. R. and Knight. L. A., 1987.

PhyCS2015-2ndInternationalConferenceonPhysiologicalComputingSystems

102

Assessing computer anxiety: Development and

validation of the computer anxiety rating scale.

Computers in Human Behavior, 3(1), pp.49-59.

Hismanoğlu, M., 2011. The elicitation of prospective EFL

teachers’ computer anxiety and attitudes. International

Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 3(3), pp.930-

956.

Isen, A. M. and Erez, A. 2006. Some measurement issues

in the study of affect. In A. Ong, & H. M. van

Dulman, eds. Oxford Handbook of Methods in Positive

Psychology New York. USA: Oxford University

Press. pp.250-265.

Kaiser, R. and Oertel, K., 2006. Emotions in HCI: An

affective e-learning system. Paper presented at the

2006 HCSNet Workshop on the Use of Vision in HCI.

Canberra, Australia, 01 November.

Karavidas, M., Lim, N. K. and Katsikas, S. L., 2005. The

effects of computers on older adult users. Computers

in Human Behavior 21(5), pp.697-711.

Kivikangas, J. M., Chanel, G., Cowley, B., Ekman, I.,

Salminen, M., Järvelä, S. and Ravaja, N., 2011. A

review of the use of psychophysiological methods in

game research. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds,

3(3), pp.181-199.

Korobili, S., Togia, A. and Malliari, A., 2010. Computer

anxiety and attitudes among undergraduate students in

Greece. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3),

pp.399-405.

Lin, T. and Hu, W., 2005. Do physiological data relate to

traditional usability indexes? Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the OZCHI 2005. Canberra, Australia,

23-25 November.

Longe, O. B. and Uzoma, O. V., 2007. Technophobia and

its impact on adults learning to use computers in south

western Nigeria. Journal of Information Technology

Impact, 7(1), pp.81-90.

Mayo Clinic, 2012. Anxiety. [online] Available at:

<http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/anxiety/DS01187

/DSECTION=symptoms> [Accessed 27 November

2013].

Merrill, D. B., 2013. Stress and anxiety. [online] Available

at:

<http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/imagepag

es/9951> [Accessed 26 November 2013].

Olufemi, O. A. and Oluwatayo, O. J., 2014. Computer

anxiety and computer knowledge as determinants of

candidates’ performance in computer-based test in

Nigeria. British Journal of Education, Society &

Behavioural Science, 4(4), pp.495-507.

Parayitam, S., Desai, K. J., Desai, M. S. and Eason, M. K.,

2010. Computer attitude as a moderator in the

relationship between computer anxiety, satisfaction,

and stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3),

pp.345-352.

Peter C., et al., 2007. EREC-II in use – Studies on

usability and suitability of a sensor system for affect

detection and human performance monitoring. In J.

Jacko ed. Human- Computer Interaction, Part III,

HCII 2007, LNCS 4552. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

pp.465-474.

Picard, R. W. and Healey, J., 1997. Affective wearables.

Personal Technologies, 1(4), pp.231-240.

Picard, R. W. and Scheirer, J., 2001. The galvactivator: A

glove that senses and communicates skin conductivity.

Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 9th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction. New Orleans, USA, 05-10 August.

Princeton University, 2013. Wordnet – A lexical database

for English. [online] Available at:

<http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=galv

anic skin response> [Accessed 26 November 2013].

Rogge, T., 2011. Stress and anxiety. [Online]. Available

at:

<http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/00

3211.htm> [Accessed 27 November 2013].

SwordMedical, 2010. Introducing the enhanced

bodymedia sensewear system. [online] Available at:

<http://www.swordmedical.ie/PRODUCTS/upload/Fil

e/Body%20Media/SW- brochure.pdf> [Accessed 13

March 2011].

Ursavas, Ö. F. and Teo, T., 2011. A multivariate analysis

of the effect of gender on computer anxiety among

elementary school teachers. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 42(2), pp.E19-E20.

ComparingtheSensorGloveandQuestionnaireasMeasuresofComputerAnxiety

103