Using a Domain-specific Modeling Language for Analyzing Harmonizing

and Interfering Public and Private Sector Goals

A Scenario in the Context of Open Data for Weather Forecasting

Sietse Overbeek

1

and Marijn Janssen

2

1

Institute for Computer Science and Business Information Systems, University of Duisburg-Essen,

Reckhammerweg 2, D-45141 Essen, Germany

2

Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology,

Jaffalaan 5, 2628 BX Delft, The Netherlands

Keywords:

DSML, e-Government, GoalML, Goal Modeling, Open Data.

Abstract:

The opening of data by public organizations can result in innovations and new business models in the private

sector. Yet, the public and private sectors may have different and sometimes interfering objectives. In this

paper, we analyze the goals of an open data business model for weather forecasting using the multi-perspective

goal modelling language GoalML. The public and private sectors partly share similar goals, but creating public

value was found to be interfering (to some extent) with the private sector objective of making profit. One of

the values of GoalML is that it clearly shows harmonizing and interfering goals. The interfering goals are one

of the explanations for a slow adoption of open data. Mechanisms need to be developed to deal with them.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past ten years, the opening of public sector

data, or ‘open data’ for short, has gained increas-

ing attention. Open data can be defined as: “non-

privacy-restricted and non-confidential data which

is produced with public money and is made avail-

able without any restrictions on its usage or distribu-

tion” (Janssen et al., 2012, p. 258). Data excluded

from this definition concern private, confidential, and

classified data. Open data can be provided by both

public or private organizations, as such, in contrast to

the previous definition it is not necessary to be col-

lected or produced with public money (O’Riain et al.,

2012). There are at least four motivating statements

to make use of open data. First, it provides greater

return on public investments. Second, policy-makers

are provided with data needed to address complex

problems (Arzberger et al., 2004). Third, it is pos-

sible to tap into the intelligence of the crowd by en-

abling citizens to participate in analyzing large quan-

tities of data sets (Surowiecki, 2004). Fourth, orga-

nizations can improve their accountability and trans-

parency (Janssen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2005). The

growth of open data does not merely come with bene-

fits, as it is also known that organizations have to deal

with adoption barriers in order to make data openly

available and to let it be used successfully (Janssen

et al., 2012). Governments release their data to prop-

agate their public values, that form the basis of the

democratic system (Moore, 1995). There seems to

be no common definition of public values (Cordella

and Bonina, 2012). However, they cannot be merely

embraced by special interest groups, as public values

should be part of society as a whole (Jørgensen and

Bozeman, 2007). In other words: “the public sector

is there for everybody, it is not the extended arm of

a particular class or group” (Jørgensen and Bozeman,

2007, p. 361). The propagation of public values by

public organizations can be directly associated with

the achievement of goals that these organizationsneed

to fulfill in order to pursue public values.

One of the problems concerns the situation where

goals of private organizations that make use of pub-

lic sector data might differ in part from goals that

public organizations have in relation to that identi-

cal public sector dataset. More precisely, one of the

complexities in open data is the involvement of or-

ganizations having different goals than the organi-

zation that is the provider of the data. In this pa-

per, both public and private sector goals related to

the opening and usage of data are analyzed to un-

derstand to what extent they are similar, harmoniz-

ing, different, or even interfering with each other. It

531

Overbeek S. and Janssen M..

Using a Domain-specific Modeling Language for Analyzing Harmonizing and Interfering Public and Private Sector Goals - A Scenario in the Context of

Open Data for Weather Forecasting.

DOI: 10.5220/0005237505310538

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development (MODELSWARD-2015), pages 531-538

ISBN: 978-989-758-083-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

can be seen that whereas the public sector is focused

on creating public values, the private sector is profit-

oriented. They will be less concerned with, for ex-

ample, ensuring social security or increasing citizen

empowerment, although they need to comply with

governmental regulations. The goal analysis will be

conducted in the context of a ‘Weather Radar’ sce-

nario, which is inspired by a weather forecasting ser-

vice operated by a Dutch private organization called

‘Buienradar’ (www.buienradar.nl), which makes use

of open data to provide real-time weather information

for their clients. Competitors of ‘Buienradar’ include

Druppel (www.druppel.nu), Shower Alarm (‘Buien-

alarm’ in Dutch, see: www.buienalarm.nl), and Drash

(dra.sh). The weather data is collected by a semi-

public meteorological organization funded by pub-

lic money. In case of Buienradar, data is collected

from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute,

of which the abbreviation of the Dutch translation

is ‘KNMI’ (www.knmi.nl). These (semi-)public and

private organizationshave goals related to the opening

and use of open data and, therefore, provide a proper

context on which our scenario is inspired.

The multi-perspective Goal Modelling Language

(GoalML) (Overbeek et al., 2015) is used to design

goal models for the Weather Radar case from the

point of view of the involved organizations. It is

shown that these goal models enable to perform dif-

ferent kinds of analyses, which includes but is not

limited to: determination of how goals are ordered

in a goal hierarchy, which goals are similar and har-

monizing, or which goals are different and even in-

terfering. There are three main reasons why GoalML

has been selected for the design of the goal models.

First, GoalML models are an integral part of enter-

prise models, which provide relevant contexts, such

as: Descriptions of resources, business process mod-

els or models of the IT infrastructure (Overbeek et al.,

2015; Frank, 2014). Second, while it is possible to

model goals with a general purpose modelling lan-

guage (GPML) like the Unified Modelling Language

(UML) or the Entity-Relationship Modelling (ERM)

language, the GoalML is actually a domain-specific

modelling language (DSML). This is for three rea-

sons: Using a GPML requires a modeler to recon-

struct relevant concepts such as various kinds of goals

from scratch, which compromises modelling produc-

tivity. Furthermore, a DSML includes specific con-

straints that prevent modelers to a certain degree from

creating erroneous models. Finally, a DSML enables

the use of a specific visual notation or, in other words,

a concrete syntax, which fosters comprehensibility.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2

describes the background of the scenario that is used

as a basis for the creation of goal models related to

the opening and using of weather data. The goal mod-

els are presented in section 3 and, subsequently, dis-

cussed in section 4. The paper ends with conclusions

and future research in section 5.

2 A SCENARIO FOR OPENING

AND USING WEATHER DATA

The motivation to stimulate organizations in opening

their data is embodied in the European Union (EU)

Public Sector Information (PSI) directive, which was

released in 2003 (EU, 2003). This directive is based

on two ideas. First, public sector data should be

made available for third parties at low prices and un-

restrictive conditions, and, second, this would ensure

a ‘level playing field’ among organizations, which

means that equal opportunities are provided for or-

ganizations. One of the objectives of the publica-

tion of open data is to facilitate the innovative use

of these data by companies (Dawes, 2010; O’Riain

et al., 2012; Neuroni et al., 2013). The European

Commissioner believes that open data boosts the Eu-

ropean economy by e40 billion per year (EC, 2010).

These prospects of the publication of open data lead-

ing to possible usage by third parties directly relate to

the development that organizations increasingly use

social media to facilitate interactions between them-

selves and their clients (Chun et al., 2012). Social

media are considered to be “a group of Internet-based

applications [...] that allow [for] the creation and ex-

change of user-generated content” (Kaplan and Haen-

lein, 2010, p. 61). The Weather Radar weather fore-

casting service uses open data collected with public

money and after enriching the data it is provided to

the users. They employ two channels to interact with

their users, which includes a Web site and an applica-

tion, or app for short, which can be downloaded and

installed on mobile devices.

The combination of open data and social media

has led to the introduction of so-called infomediary

business models, which “can be initiated by [...] pub-

lic or private [organizations] and are aimed at sup-

porting the coordination between open data providers

and users” (Janssen and Zuiderwijk, 2014, p. 2). A

business model in general contains the rationale and

the elements required to accomplish certain organiza-

tional objectives (Keen and Qureshi, 2006). The rev-

enue models of the Web site and the app are slightly

different, as the Web site primarily depends on adver-

tisements, whereas the app provides advertisements

and options to buy additional content within the app

itself. For example, this includes the options to buy 3

MODELSWARD2015-3rdInternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

532

Data provider

Meteorological Institute

Users

(citizens, businesses, public

organizations, researchers, …)

Weather Radar

(website, app)

Figure 1: Open data network for the Weather Radar scenario.

hours or 24 hours rain forecasts, information about

thunder, hail and sun power. The app is based on

a so-called ‘single-purpose app’ infomediary busi-

ness model (Janssen and Zuiderwijk, 2014). “Single-

purpose apps provide real-time services such as infor-

mation about weather, quality of restrooms, vehicles,

houses, and pollution. These apps often provide a sin-

gle function, based on one type of provided open data.

The app processes the data and presents it visually

for the ease of the users” (Janssen and Zuiderwijk,

2014, p. 11). The ‘open data network’ for this sce-

nario is shown in figure 1. The data is primarily based

on information collected by a meteorological insti-

tute, which is the semi-public open data provider. The

private organization offering the weather forecasting

service extrapolates the data to make predictions and

visualizes the data on a geographical map. For users,

this is complicated to realize by themselves and as

such there are hardly any users who use this raw open

data correctly (Janssen and Zuiderwijk, 2014). The

line at the top of figure 1 indicates that it is, however,

possible to use raw open data directly without relying

on an infomediary as a liaison party.

3 GOALS FOR OPENING AND

USING DATA IN THE

SCENARIO

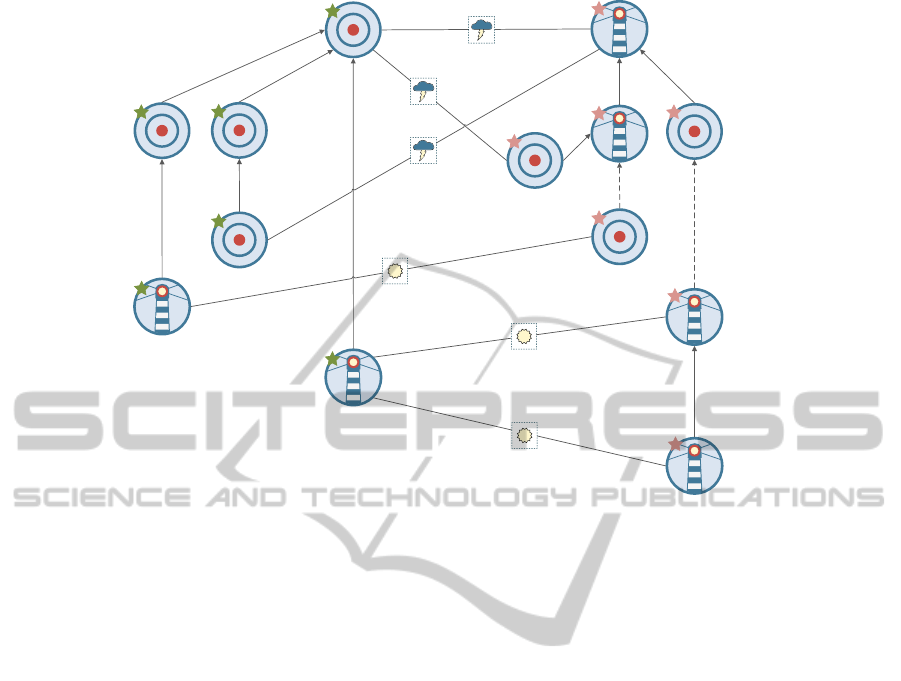

Figure 2 presents the goal model of a meteorological

institute being the semi-public sector data provider.

This goal model includes the goals that this institute

wants to achieve by opening up their weather data to

be used by third party organizations such as infome-

diary organizations providing a weather forecasting

service. Figure 3 shows the goal model of an infome-

diary that uses open weather data to deliver a weather

forecasting service to possible users. The goal models

have been designed by using GoalML. The diagrams

include both so-called engagement goals and sym-

bolic goals (Overbeek et al., 2015). An engagement

goal is a goal of which the desired result is quantifi-

able, for example, the goal ‘increase citizen services’

shown in figure 2 is an engagement goal, as it is quan-

tifiable whether the number of new services have in-

deed increased. Motivations and the performance of

employees responsible for goal achievement can also

be made more explicit by means of such engagement

goals. An engagement goal is visualized as a target.

A symbolic goal is a goal of which the desired result

is not directly quantifiable and includes a qualitative

aspect and is visualized as a lighthouse. An example

of a symbolic goal found in figure 2 is ‘increase citi-

zen satisfaction’, as the increase of citizen satisfaction

is not directly quantifiable. A symbolic goal ‘increase

trust’ is shown on top of figure 2. The star symbol

with the number one inside the star shows that this

specific goal has the highest priority.

The circles shown on the top right of each of the

goals depict specific goal matter, further specifying

the goal content. A yellow hexagon with a plus sym-

bol in it is part of the goal matter of the mentioned

symbolic goal. This shows that something needs to

increase upon achievement of the goal, in this case

the trust of the semi-public agency. In contrast to the

hexagon with a plus symbol, a hexagon with a minus

symbol indicates that something needs to decrease.

The symbol of an eye looking at a diamond as part

of the goal matter of the symbolic goal shows that

the goal content is qualitative in nature. When fur-

ther interpreting the diagrams shown in figures 2 and

3, it can be determined that two other symbols can be

part of the goal matter, which are the indicator sym-

bol and the ‘object’ symbol. For example, the goal

matter of the ‘increase added value’ goal shown in

figure 3 contains an indicator symbol, expressing that

the goal content is quantitative in nature. The ‘ob-

ject’ symbol is illustrated by means of a combination

of a circle, a triangle, and a rectangle. This symbol

is used to indicate that an explicit ‘object’ is part of

the goal content. For example, the ‘object’ symbol

in the goal matter of the ‘keep existing users’ goal as

part of figure 3 indicates that a ‘user’ is a specific ob-

ject to take into account as part of the goal content.

Next to the two different kinds of goals and the goal

content, there are three kinds of relationships that can

be found in both diagrams: A causal relationship, a

meansend relationship, and a mathematical relation-

ship. The causal relationships are indicated by means

of domino pieces, together with an arrow that points

in the upward direction indicating a positive causal

relationship. For example, the goal ‘increase citizen

satisfaction’ found in figure 2 has a positive causal

UsingaDomain-specificModelingLanguageforAnalyzingHarmonizingandInterferingPublicandPrivateSectorGoals-

AScenariointheContextofOpenDataforWeatherForecasting

533

Increase

transparency

1

Transparency

Increase

accountability

1

Accountability

Increase trust

1

Trust

Increase

citizen

satisfaction

1

Citizen

satisfaction

Increase

citizen

empowerment

3

Citizen

empowerment

Increase data

provider

visibility

4

Data provider

visibility

Increase data

scrutinization

6

Data

scrutinization

Increase

citizen

services

Citizen services

Increase

quality of

citizen

services

2

Quality of citizen

services

Keep data

access equal

5

Data access

Increase

quality of

policy-making

processes

5

Quality of policy-

making

processes

Increase new

insights in

public sector

7

New insights in

public sector

Increase

stimulation of

knowledge

development

8

Stimulation of

knowledge

development

3

Figure 2: Goal model of a semi-public meteorological institute for opening weather data.

MODELSWARD2015-3rdInternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

534

Increase

continuity

1

Continuity

Increase profit

2

Profit

Increase

added value

4

Added value

Decrease

data access

costs

6

Data access

costs

Increase

innovation

4

Innovation

Increase

efficiency

5

Efficiency

Increase

service quality

4

Service quality

Increase

differentiation

5

Differentiation

Increase

users

Users

3

Increase data

quality

6

Data quality

Keep existing

users

3

Users

Figure 3: Goal model of an infomediary organization that uses open weather data.

effect on the ‘increase trust goal’. The meansend re-

lationships are combined with the causal (and other)

relationships shown in the diagrams. For example, the

goals ‘keep existing users’, ‘increase added value’,

and ‘increase service quality’ shown in figure 3 are a

means to support in reaching another final goal, which

is the ‘increase users’ goal in this case. Finally, the

positive mathematical relationship between, for ex-

ample, the goals ‘increase efficiency’ and ‘increase

profit’ indicates that increasing the efficiency has a

positive mathematical effect on the actual profit that

is made by the infomediary.

4 DISCUSSION

When comparing both diagrams, there are differences

and interferences that can be identified. Fortunately,

there are also similarities and harmonious circum-

stances that can be identified. First, identified dif-

ferences and interferences will be described. Sec-

ond, the similarities and harmonious circumstances

are discussed. Obviously, it can be seen that the goal

model of the semi-public agency for opening weather

data contains more goals and the goal hierarchy itself

is deeper. Consequently, for a semi-public agency like

a meteorological institute the structure of lower-level

goals that need to be achieved as a result of opening

up weather data is more complex and it seems more

demanding to achieve the topmost goal in the hierar-

chy. This has to do with the fragmented government

structure in which different organizations have differ-

ent priorities (Kraaijenbrink, 2002). For example, the

Dutch Ministry of Economics focuses on value cre-

ation and innovation by businesses. The Dutch Min-

istry of Interior has prioritized goals related to trans-

parency, reputation, and improved democracy (Plas-

terk, 2014). For the meteorological institute as part of

the scenario as discussed in section 2, trust, account-

ability, and citizen satisfaction are high on the agenda

as well. This means that the opening of data requires

prioritizing goals and making trade-offs. When in-

terpreting the goals that have the highest priorities,

there seem to be big differences between the open

data provider and the infomediary. The top priorities

for the data provider have to do with increasing trust,

transparency, accountability, and citizen satisfaction

by opening data, while the top priority for the info-

mediary is to increase its continuity by using open

data. For the meteorological institute being the data

provider, an increase in trust can be achieved after

achieving an increase in transparency, accountability,

UsingaDomain-specificModelingLanguageforAnalyzingHarmonizingandInterferingPublicandPrivateSectorGoals-

AScenariointheContextofOpenDataforWeatherForecasting

535

Increase

innovation

4

Increase

efficiency

5

Increase

users

3

Increase data

quality

6

Keep existing

users

3

Increase

citizen

satisfaction

1

Increase

citizen

empowerment

3

Increase data

scrutinization

6

Increase

citizen

services

Keep data

access equal

5

Increase new

insights in

public sector

7

Increase

stimulation of

knowledge

development

8

3

Increase profit

2

Figure 4: Harmonizing and interfering goals related to open weather data.

and citizen satisfaction. When interpreting this goal,

however, it is assumed that an ‘increase in trust’ can

be interpreted differently by those who are responsi-

ble to achieve this goal. People can come up with

different interpretations in case they want to deter-

mine when a governmentagency can be ‘trusted’. The

term trust is somehow related to terms like hope, con-

fidence, belief, and commitment and deals with ac-

tively anticipating and facing an unknown future (Sz-

tompka, 1999, p. 25). When acting in uncertain

and uncontrollable conditions, people take risks and

make bets about the future. As such, this key goal of

the open data provider might be understood in many

different ways, which makes the achievement of this

goal seemingly more complex than achieving the key

goal(s) of the infomediary.

For the infomediary, the achievement of an in-

crease in continuity directly relates to the achieve-

ment of an increase in profit. The goal of increas-

ing their profit is reflected in their business model,

as advertisements and options to buy content within

the mobile app are provided. The goal to increase

profit that is related to the private value to increase

profit might interfere with the public value to in-

crease citizen satisfaction. Analogous to how soft-

ware is developed under the GNU General Public Li-

cense (see: www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.en.html), a

government agency that offers open data wants end

users to use, share, and extrapolate this data for free.

Users can get bothered by advertisements while us-

ing the weather forecasting service and they might

not want to be bothered with additional content that

must be bought to get access to more advanced fea-

tures or additional data. Especially when the mobile

app allows users to pay for features that allow ac-

cess to additional data, there is interference between

the ‘increase profit goal’ of the infomediary and the

goal ‘keep data access equal’ of the semi-public data

provider. As can be seen in figure 2, when this goal

cannot be achieved, the possibility to achieve the re-

lated goals that are higher in the hierarchy, such as

‘increase citizen empowerment’ and ‘increase citizen

satisfaction’ is threatened as well. Another side-effect

of providing the users the possibility to pay additional

content within the app is that users might become dis-

appointed after realizing they have to pay for addi-

tional features or content after having downloaded an

app that was downloadable at zero costs. This also

threatens the goal of the semi-public data provider

to increase citizen satisfaction. Although there are

differences and interferences to be found when com-

paring the key goals of both models, an increase in

the trust level of the data provider presumably con-

tributes to achievement of the ‘increase continuity’

goal of the infomediary. It is assumed that the con-

tinuity of an infomediary is easier to protect in case

MODELSWARD2015-3rdInternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

536

the used open data originates from a trustworthy data

provider. However, differentiating from other com-

petitors in the market and asking citizens to pay com-

mercial rates in order to reach some higher-order goal

will never fit with public sector goals, as these kind

of goals are not concerned with commercial interests.

Another harmonizing aspect found in the two goal

models is related to the users of the weather forecast-

ing service. Achieving the goal ‘increase citizen sat-

isfaction’ found in the goal model of the meteorolog-

ical institute will probably have a positive effect on

the goal ‘keep existing users’. The assumption un-

derlying this statement is that once the satisfaction

of citizens that are also existing users of the weather

forecasting service increases, the probability they will

keep using this service increases as well.

The goals ‘increase data scrutinization’ as part of

the goal model of the meteorological institute and ‘in-

crease data quality’ as part of the infomediary goal

model are also considered to be in harmony with each

other. If the meteorological institute increases the

possibilities to scrutinize its open data, this might lead

to a further improvement of the data quality. The goal

‘decrease data costs’ is considered to be in harmony

with the goal ‘keep data access equal’. The goals

‘increase stimulation of knowledge development’ and

‘increase new insights in public sector’ are in har-

mony with the goal ‘increase innovation’. The in-

fomediary might benefit from an increase in new in-

sights in the public sector which can lead to an in-

crease in innovation for the infomediary and, vice

versa, the open data provider might benefit from in-

novation in the private sector to gain new insights

that are relevant for them. Figure 4 shows the result-

ing goal model in which it has been visualized which

goals are in harmony with each other and which goals

are interfering with each other. Goals that have rela-

tionships with a symbol of a sun attached to it show

that these goals are in harmony with each other. The

symbol with a dark cloud and a lightning flash indi-

cates that goals are interfering. The priority symbols

of those goals that belong to the open data provider

have been colored green, while the priority symbols

attached to the goals belonging to the infomediary

have a red color. Note that although there are goals

shown in figure 4 that are harmonizing or interfering,

this does not imply that this situation should be identi-

cal for other open (weather) data scenarios. Whether

goals are in harmony or interfering also depends on

which measurements are taken to achieve goals. For

example, there might be ways to increase profit with-

out interfering with the goal ‘increase citizen satis-

faction’, or, the other way around, there might also

be new insights created in the public sector that might

not boost innovation in the private sector.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

In the past decade, the opening of public sector data

steadily but slowly grew in popularity. One of the

complexities in open data concerned the difference

in goals of those organizations involved in the open-

ing and usage of the data. In this paper, a scenario

has been presented that involved a semi-public mete-

orological institute, which released weather data for

the public. The scenario also included an infomedi-

ary, a private organization that used and extrapolated

this open weather data in order to offer an advanced

weather forecasting service to its users. Both pub-

lic and private sector goals related to the usage of

open data have been analyzed to understand to what

extent goals related to open data in the public and

private sectors are similar, harmonizing, different, or

even interfering with each other. GoalML is a DSML

that is suitable for modelling goals in the public and

private sectors and can be used to support organiza-

tions with developing, using, and maintaining goal

models. The priorities that public organizations as-

sign to their goals might be different per organization

and is dependent of their overall role within the pub-

lic administration. Already within the public admin-

istration goals are diverse and might be interfering.

Furthermore, the analysis shows clearly the conflict

of interest between the private and the public sec-

tor. In particular, it is shown that the private sector

goal to increase profit might interfere with the pub-

lic sector goal to increase citizen satisfaction and the

goal ‘keep data access equal’. The interfering goals

might be one of the reasons why the realization of

open data by public organizationscan be problematic.

Due to requirements on open data usage, private orga-

nizations might think that that sometimes interfering

goals result in choices that might not favor their inter-

est. However, it are not merely the public and private

sector goals related to open data that result in inter-

ferences, but the implementation of measurements to

achieve these goals influences relationships between

public and private sector goals as well. It might be

that mechanisms can be developed that are accept-

able for both the public and private sectors. As such,

we recommend public and private sectors to start dis-

cussing the release and use of open data and come

up with mechanisms that can satisfy the requirements

of both sectors. This recommendation is also inher-

ent to future research. GoalML offers stakeholders of

open data in the public and private sectors the pos-

UsingaDomain-specificModelingLanguageforAnalyzingHarmonizingandInterferingPublicandPrivateSectorGoals-

AScenariointheContextofOpenDataforWeatherForecasting

537

sibility to act as an instrument in further analyzing

and discussing models and scenarios to satisfy intra-

sectorial requirements. An important task to perform

in this context is to make GoalML even more suit-

able for use in different contexts such as goal analysis

of ‘open data networks’, as GoalML is rich in detail

which makes it suitable for advanced users but less

suitable for more novice users at first. Another part of

future research deals with the question how goal mod-

els can be integrated into software with the intention

to provide different forms of computer-based support

for, e.g., strategy formulation, goal achievement, and

enterprise management in general. A possible form of

computer-based support is to use the information pre-

sented in goal models for deductive purposes. For ex-

ample, information from goal models provide a foun-

dation for the generation of rules that need to be ad-

hered to when conducting tasks or processes that are

related to a goal. By adhering to these rules, it is pos-

sible to steer in a direction that would lead to goal

achievement. This part of future research also relates

to creating models at runtime and self-adaptive sys-

tems, which implies that a system adapts its structure,

functions, or processes to a (manually) modified goal

system. A self-adaptive system might also modify the

goal system itself to better cope with a changing en-

vironment.

REFERENCES

Arzberger, P., Schroeder, P., Beaulieu, A., Bowker, G.,

Casey, K., Laaksonen, L., Moorman, D., Uhlir, P.,

and Wouters, P. (2004). An international framework

to promote access to data. Science, 303(5665):1777–

1778.

Chun, S., Luna-Reyes, L., and Sandoval-Almaz´an, R.

(2012). Collaborative e-government. Transforming

Government: People, Process and Policy, 6(1):5–12.

Cordella, A. and Bonina, C. (2012). A public value per-

spective for ict enabled public sector reforms: A theo-

retical reflection. Government Information Quarterly,

29(4):512–520.

Dawes, S. (2010). Stewardship and usefulness: Policy prin-

ciples for information-based transparency. Govern-

ment Information Quarterly, 27(4):377–383.

EC (2010). Riding the wave: How Europe can gain form

the rising tide of scientific data. Final report of the

High Level Expert Group on Scientific Data, Euro-

pean Commission, Brussels, Belgium, EU.

EU (2003). Directive 2003/98/EC of 17 november 2003 on

the re-use of public sector information. Official Jour-

nal of the European Union L 345/90, The European

Parliament and the Council of the European Union,

Brussels, Belgium, EU.

Frank, U. (2014). Multi-perspective enterprise model-

ing: Foundational concepts, prospects and future re-

search challenges. Software and Systems Modeling,

13(3):941–962.

Janssen, M., Charalabidis, Y., and Zuiderwijk, A. (2012).

Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and

open government. Information Systems Management,

29(4):258–268.

Janssen, M. and Zuiderwijk, A. (2014). Infomediary busi-

ness models for connecting open data providers and

users. Social Science Computer Review, 32(5):694–

711.

Jørgensen, T. and Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values: An

inventory. Administration & Society, 39(3):354–381.

Kaplan, A. and Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world,

unite! The challenges and opportunities of social me-

dia. Business Horizons, 53(1):59–68.

Keen, P. and Qureshi, S. (2006). Organizational transforma-

tion through business models: A framework for busi-

ness model design. In Proceedings of the 39th Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS

2006), pages 1–10. Computer Society Press.

Kraaijenbrink, J. (2002). Centralization revisited? Prob-

lems on implementing integrated service delivery in

the Netherlands. In Traunm¨uller, R. and Lenk, K.,

editors, Electronic Government: First International

Conference, EGOV 2002 Aix-en-Provence, France,

September 26, 2002 Proceedings, volume 2456 of

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 10–17.

Springer, Berlin, Germany, EU.

Moore, M. (1995). Creating Public Value: Strategic Man-

agement in Government. Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Neuroni, A., Riedl, R., and Brugger, J. (2013). Swiss ex-

ecutive authorities on open government data – pol-

icy making beyond transparency and participation. In

Proceedings of the 46th Hawaii International Confer-

ence on System Sciences (HICSS 2013), pages 1911–

1920. Computer Society Press.

O’Riain, S., Curry, E., and Harth, A. (2012). XBRL and

open data for global financial ecosystems: A linked

data approach. International Journal of Accounting

Information Systems, 13(2):141–162.

Overbeek, S., Frank, U., and K¨ohling, C. (2015). A lan-

guage for multi-perspective goal modelling: Chal-

lenges, requirements and solutions. Computer Stan-

dards & Interfaces, 38:1–16.

Plasterk, R. (2014). Reactie op ARK Trendrapport Open

Data. Kamerbrief 2014-0000486923, Ministry of the

Interior, the Hague, the Netherlands, EU. In Dutch.

Surowiecki, J. (2004). The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the

Many are Smarter than the Few and How Collective

Wisdom Shapes Business Economies, Societies and

Nations. Doubleday, New York, NY.

Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust: A Sociological Theory. Cam-

bridge University Press, New York, NY.

Zhang, J., Dawes, S., and Sarkis, J. (2005). Exploring stake-

holders’ expectations of the benefits and barriers of e-

government knowledge sharing. Journal of Enterprise

Information Management, 18(5):548–567.

MODELSWARD2015-3rdInternationalConferenceonModel-DrivenEngineeringandSoftwareDevelopment

538