Privacy and Security Concern of Online Social Networks from User

Perspective

Al Amin Hossain and Weining Zhang

Department of Computer Science, The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Privacy, Online Social Networks, SNS, default settings.

Abstract:

Personal data sharing has emerged as a popular activity on online social networks such as Facebook, Google+,

Twitter. As a result, privacy issues have received significant attention in both the research literature and the

mainstream media. In this study, we designed a set of questions aimed to learn about user views of online

privacy, user knowledge about OSNs privacy settings, and user awareness of privacy disclosure. Our goal is to

find out from the users whether and how well users are knowledgable of, satisfied with, and able to effectively

use available privacy settings. The information obtained from this study can be used to help OSNs adjust

their privacy settings to better match user expectations, and help privacy advocates design better ways to help

users control the disclosure of their online information. We collected answers to the questions from a group

of 377 users, selected via several methods, who have experiences with multiple OSNs, including Facebook,

Google+, and LinkedIn. We analyzed the data with respect to user demographics. Our study shows that 44%

of the users lack the knowledge about privacy policies and mechanisms of their OSNs; 34% and 41% of the

users, respectively, are seriously and somewhat concern about their privacy protection; and 80% of the users

do not think their OSNs have provided sufficient privacy control or default privacy settings that match their

expectations. Based on our analysis, we propose several options for OSNs and OSN users to improve the user

privacy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, the evolution of Internet tech-

nologies led to significant growth of online so-

cial networks (OSNs), such as Facebook, LinkedIn,

Google+. According to some study (key, ), as of Jan-

uary 2014, 74% of users who have access to the In-

ternet are also members of some OSNs. As a result,

OSNs have become a part of people’s daily life and

a promising mechanism for people to connect to and

interact with friends, colleagues and relatives (Pagoto

et al., 2014). OSNs can even help users to recon-

nect with old friends who have long been lost in con-

tact. The friendly and social environment of OSNs

is very attractive to users and makes it easy for users

to disclose information about themselves and about

their connections with other users. Such information

can include confidential details such as date of birth,

email address, educational background, relationship

statuses, personal photos, phone numbers, and details

about the working place. However, most of OSN

users may not give much thought about if and how

their personal information can be disclosed, and how

the disclosure of their personal information may neg-

atively impact their lives. On the other hand, OSNs

may be requested by government or law enforcement

agencies to turn over their user information. These

types of practices can cause severe violation of user

privacy.

Protecting user privacy has become a fundamen-

tal requirement of OSNs. Recent incidences, such as

iCloud data breaches, clearly indicate the importance

of privacy protection as users share personal informa-

tion. Although every OSN has provided some privacy

settings that users can customize, study (Xiao and

Tao, 2006; Lappas, 2010; Lappas et al., 2009; Net-

ter, 2013; Krishnamurthy and Wills, 2008; Liu, 2011;

Johnson et al., 2012; Madejski et al., 2012; Fang

and LeFevre, 2010) has indicated that many OSNs

change their privacy settings frequently and often qui-

etly based on some non-disclosed considerations. In

fact, default privacy settings of many OSNs are al-

most always tend to be more open (a.k.a. weaker)

than what users would desire. As a result, more per-

sonal information of more users is put at risk of pri-

vacy disclosure than necessary. However, protecting

privacy of users should not be the sole responsibility

of OSNs. It is equally important that OSN users be

246

Hossain A. and Zhang W..

Privacy and Security Concern of Online Social Networks from User Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0005318202460253

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP-2015), pages 246-253

ISBN: 978-989-758-081-9

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

aware of their online environment, the available pri-

vacy settings and the meaning of those settings.

In this regard, a clear understanding of user per-

spectives about their online privacy protection can

help to explain why users who are conscious about

privacy may have difficulty to manage their privacy

settings, and why many users could not set default pri-

vacy settings appropriately when sharing their infor-

mation with friends. For example, one study (Bosh-

maf, 2011) revealed that on average, 80% of Face-

book users accepted friend request from a person

whom they know very little about, even if they and

stranger have more than 11 mutual friends. Such

study raised the awareness of significant privacy risks,

since accepting friend requests from strangers can

easily lead to disclosure of personal information to

adversary, someone who collects user personal infor-

mation for bad intensions. Another study (Liu, 2011)

has found that OSN (e.g., Facebook ) privacy settings

match users expectations only 37% of the time, indi-

cating that for most of the time, the available OSN

privacy settings are inappropriate.

There have been a number of previous studies

(Xiao and Tao, 2006; Netter, 2013; Liu, 2011; Made-

jski et al., 2012; Beato and Peeters, 2014) on privacy

settings of online social networks. Most of these stud-

ies (Liu, 2011; Johnson et al., 2012; Madejski et al.,

2012; Fang and LeFevre, 2010; Miltgen and Peyrat-

Guillard, 2014) were based on small samples involv-

ing 200 to 300 individuals. It is not clear if the results

of these studies can be generalized. Another aspect of

these studies is that they focused on privacy risks in-

volving adversaries outside of OSNs and did not con-

sider privacy risks that might involve people inside the

OSNs, such as people in friends network. In addition,

no previous study has analyzed privacy issues with re-

spect to user demographics. This is a shortcoming be-

cause user perspective regarding online privacy may

depend on their gender, age, and cultural background.

Finally, previous studies investigated privacy settings

of Facebook, but no research has considered other

significant OSNs such as Google+, Linkedln, Twit-

ter, RenRen, WeChat, MySpace, and Hi5. The results

of these studies may not be applicable to other OSNs

due to the differences among these OSNs in terms of

sizes, user types, social activities, relationship types,

and privacy settings.

In this paper, we report on a study of user perspec-

tives about OSN privacy issues that includes multiple

OSNs. In this study, we designed a set of questions

aimed to learn about user views of online privacy,

user knowledge about OSNs privacy settings, and user

awareness of privacy disclosure. Our goal is to find

out from the users themselves whether and how well

users are knowledgable of, satisfied with, and able to

effectively use available privacy settings. The infor-

mation obtained from this study can be used to help

OSNs adjust their privacy settings to better match user

expectations, and help privacy advocates design bet-

ter ways to help users control the disclosure of their

online information. We collected answers to the ques-

tions from a group of 377 users, selected via several

methods, who have experiences with multiple OSNs,

including Facebook, Google+, and LinkedIn. We ana-

lyzed the data with respect to user demographics. Our

study shows that 44% of the users lack the knowledge

about privacy policies and mechanisms of their OSNs;

34% and 41% of the users, respectively, are seriously

and somewhat concern about their privacy protection;

and 80% of the users do not think their OSNs have

provided sufficient privacy control or default privacy

settings that match their expectations. Based on our

analysis, we propose several options for OSNs and

OSN users to improve the user privacy.

The remainder of the paper is organized as fol-

lows. In Section 2, we briefly discuss previous works

related to our study. In Section 3, we describe our sur-

vey method including the design of questions and the

selection of correspondents. In Section 4, we analyze

the survey results and provide our recommendations.

Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 RELATED WORKS

In this section, we briefly describe some research

work related to our study.

Tucker et al. (Tucker, 2014) investigated how the

perceived control of users over their personal infor-

mation affects the likelihood that they will click ads

on a social networking website. Their found that

0.03% of users are likely to click advertisements that

claim to improve user privacy settings.

Park et al. (Park et al., 2014) developed a frame-

work to provide trusted data management in OSNs.

They provided an approach for users to determine

their optimum levels of information sharing. How-

ever, it is not clear how users can determine whether

they are appropriately protected by online social net-

works.

Liu et al. (Liu, 2011) compared the desired and

the actual privacy settings of 200 Facebook users.

They defined a measure of the inconsistency between

desired and actual privacy settings, and surveyed the

users to learn the inconsistency of their privacy set-

tings. The study found that almost 36% of users

keep their default privacy settings and for only 37%

of time, the default privacy settings match user ex-

PrivacyandSecurityConcernofOnlineSocialNetworksfromUserPerspective

247

pectations. In those cases where the default settings

also not match user’s expectation, most of the users

continuously use the default privacy settings.

Maritza et al. (Johnson et al., 2012) studied 260

Facebook users about their strategies to reconcile pri-

vacy concerns with the desire of online content shar-

ing. They identified user privacy concerns regarding

sensitive posts and users’ privacy strategies. Their re-

sults indicated that existing privacy controls can ef-

fectively deal with outsider threat (by members not in

users friend network), but are not effective for insider

threat (by members of the friend network who dynam-

ically become inappropriate audiences based on the

context of a post).

Madejski et al (Madejski et al., 2012) studied pri-

vacy settings in Facebook. They measured user inten-

tions of sharing information and investigated potential

violations in actual privacy settings in user accounts.

Their results showed that there is a serious mismatch

between user expectations and the actual privacy set-

tings.

Miltgen et al (Miltgen and Peyrat-Guillard, 2014)

studied cultural and generational influences on pri-

vacy concerns in seven European countries. Their

study focused on two groups (i.e., young and adults)

of people.

In addition to the aforementioned studies, there

are also studies of privacy mechanisms for OSNs.

Fang et al.(Fang and LeFevre, 2010) proposed a

template for designing a social networking privacy

wizard based on an active learning technique, called

uncertainty sampling. The method learns user privacy

preferences according to a set of rules and uses the

acquired knowledge to configure user privacy settings

automatically.

Hu et al (HongxinHu et al., 2012) presented

a method to enable collaborative data sharing for

Google+ users. It allows a user to share his/her own

data with a selected group of users. This offers a bet-

ter privacy control than other OSNs where users can

only choose between disclosure to nobody and disclo-

sure to the whole world. However, they did not offer

any mechanism to enable privacy control over data

that are owned by multiple users.

Fire et al. (Michael Fire, 2012) presented a so-

cial privacy protector for Facebook users. It provides

three protection layers. The first layer allows users to

select most suitable privacy settings by a single click.

The second layer notifies users about the number of

applications installed on their profiles which may ac-

cess their private information. The third layer, identi-

fies those friends whom are suspected as fake profiles.

Table 1: Abbreviation index.

Definition Abbreviation

Online Social Networks OSNs

Social Networking Sites SNSs

Date of Birth DoB

International Students Program EIS

The University of Texas at San

Antonio

UTSA

Principal Investigator PI

Online Social Networking Site OSNS

3 METHODOLOGY OF THE

STUDY

In this Section, we describe the survey questions and

our data collection method.

3.1 Survey Questions

Our goal is to study user perspective about the on-

line privacy and their awareness of privacy settings in

OSNs. We designed a set of questions (See Table 2) to

collect several types of information from OSN users.

Questions 1 to 4 are intended to collect demographics

information of the respondent. Questions 5 to 7 ask

about user’s general attitude towards OSNs. Ques-

tions 8 and 9 collect general information about user

attitude towards online privacy. Questions 10 and 11

ask about user attitude towards privacy policy and de-

fault privacy settings of OSNs. Questions 12 to 15

ask about user opinion regarding the use of their on-

line personal information. Question 16 ask about user

attitude towards online advertisement.

The answer to Question 1 is a specific country se-

lected from the given list. The answer to Question 2 is

male, female or prefer not to disclose. The answer to

Question 3 is a choice from a list of age ranges {15-

20, 21-25, 26-30, 31-35, 36+}. The answer to Ques-

tion 4 is a choice among {architect, doctor, engineer,

government employee, professor, researcher, student,

others}. The answer to Question 5 is a choice from

{like OSNs very much, like some part of OSNs, do

not like}.The answer to Question 6 is a choice from

{almost always, every day, twice a day, once a week,

twice a month, once a month, it depends}. The an-

swer to Question 7 is one or more choice from a list

of OSNs. The answer to Question 9 and Question 14

is a choice from {absolutely concern, concern, some-

what concern, does not concern, do not care, others}.

The answer to Question 10 is a choice from {read,

read some part, did not read, only know from friend,

did not know such policy exist, do not care}. The

answer to Question 11 is a choice among {yes, some-

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

248

Table 2: A Set of Questions Used in the Survey.

# Question Types of

Answers

1 Where do you live? Country

2 What is your gender? Female/Male

3 How older are you? Age ranges

4 What is your profession? Selected

profession

5 How much do you like OSNs? Likeness

scale

6 How often do you get online

in OSNs?

Frequency

7 Which OSNs do you use? Several

options

8 Do you concern about your

privacy while you use OSNs?

Yes/No

9 How much do you concern

about your privacy while using

OSNs?

Concern scale

10 Have you read the privacy

policy of your OSNs?

Scale

11 Are you satisfied with the

default privacy settings of

your OSNs?

Satisfaction

scale

12 Do you agree for your OSNs

to sell your personal

information?

Agree/Disagree

13 Do you agree for governments

to access your personal

information from your OSNs?

Agree/Disagree

14 How much do you concern

that friends may misuse your

photos or personal

information?

Concern scale

15 Do you agree to disclose your

profession information by

OSNs?

Agree/Disagree

16 Do you think OSNs should

remove advertisement from

your front page?

Agree/Disagree

what, not at all}. The answers to Questions 12, 13,

15, and 16 are choices from {strongly agree, agree,

neutral, disagree, strongly disagree}.

3.2 Data Collection

A challenge to this and other similar studies is to col-

lect accurate data from a large number of respondents.

A standard method is to draw a random sample from

the population. One way to do this is to visit randomly

selected profiles and ask the user of the profile to an-

swer the questions. However, this often results in low

response rate and a low accuracy of data. So in this

study, we collected data from three sources: a group

of students enrolled in a class, a group of randomly

selected students at The University of Texas as San

Table 3: Demographics of Respondents:Age, Profession

and OSNs vs Gender.

Male

297

(78.78%)

Female

80

(21.22%)

Age

5-20 4 4

21-25 53 24

26-30 184 45

31-35 40 0

36-90 16 7

Profession

Architect 2 3

Doctor 7 6

Engineer 121 15

Government Employee 5 6

Professor 11 2

Researcher 38 4

Student 108 40

Other 5 4

OSNs

Blogster 3 2

Facebook 246 79

Foursquare 7 4

Google+ 63 18

Hi5 9 3

Linkedln 124 21

MySpace 4 1

Twitter 47 17

Others 12 2

Table 4: Popular Online Social Networks Users.

Online Social Networks Total Numbers

of User

Ratio of

Total

Respondent

Blogster 5 2%

Facebook 325 86%

Foursquare 11 3%

Google+ 80 22%

Hi5 12 3%

Linkedln 145 39%

MySpace 5 2%

Twitter 64 17%

Others 14 4%

Antonio (UTSA), and a group of users of Facebook,

Google+ and LinkedIn.

There were 45 students in the class with 30 male

and 15 female. All of the students were in the age

range between 26-30. The group of UTSA students

consisted 90 students who are not in the class. How-

ever, few of the students were not willing to provide

the survey answers. We got only 60 peoples to re-

spond, including 53 male and 7 female. Each person

in these two groups was interviewed personally and

individually. Each of them was requested to answer

the set of questions listed in Table 2. Each person of

these two groups is a user of at least one OSN.

The third group consists of the set of 665 friends

of the first author of this paper in Facebook, Google+

and LinkedIn at the time of this study. We did not con-

tact randomly selected users in these networks in or-

der to assure the accuracy of the data (because friends

PrivacyandSecurityConcernofOnlineSocialNetworksfromUserPerspective

249

are more inclined than random strangers to answer

survey questions truthfully and we can verify the de-

mographics of the respondents). For each person in

the third group, we provided a Google survey form

with all questions listed in Table 2.

In total, we contacted 800 persons including those

interviewed and those polled online, and received an-

swers to our questions from 377 individuals. We no-

ticed that although only friends were invited to an-

swer the questions, a number of respondents still did

not provide accurate answers due to various reasons,

such as personal concerns, lack of motivation, and

poor memory.

4 ANALYSIS AND EVALUATIONS

In this section, we present an analysis of the data we

collected from the three groups of individuals.

4.1 Demographics of Respondents

Table 3 summarizes the demographics of the respon-

dents. Based on this table, 78.8% of respondents are

male and 21.2% are female. Interestingly, 91.77% of

the respondents are in age between 21 and 35, and

75.55% of respondents are either engineers or stu-

dents. This is consistent with our impression that the

generation growing up with the Internet and profes-

sionals relying on computers tends to use OSNs more

than other generations and other professionals. This

trend is similar among the males and the female re-

spondents.

Table 4 shows the numbers of respondents using

various OSNs. According this table, 86% of respon-

dents are users of Facebook, 39% users of LinkedIn,

22% users of Google+, and 17% users of Twitter. In

addition, our data also shows that around 30% of the

respondents are users of both Facebook and LinkedIn,

and 19% of the respondents are users of both Face-

book and Google+.

4.2 User Attitudes Towards OSNs

In this study, we analyze user attitudes towards using

OSNs based on answers to our Question 5 on how

much users like OSNs and Question 6 on how often

users use OSNs.

Fig.1 shows the overall answers to Question 5. It

indicates that 38% of the respondents like OSNs very

much, 58% of the respondents like some part of the

functionality of OSNs, and only 3% of the respon-

dents do not like OSNs at all. A further analysis

also shows that among female respondents, 32% like

Figure 1: Answers to Question 5 “How much do you like

OSNs?”.

Figure 2: Answers to Question 6 “How often do you get

online in OSNs?”.

OSNs very much and 68% like some part of OSNs,

and among male respondents 40% like OSNs very

much and around 59% ike some part of OSNs re-

spectively. In terms of age groups, 39% of respon-

dents in age group of 21-25 like OSNs very much,

much higher than other age groups. These results

suggest that there is much room for improvement of

OSNs and further study is needed to determine ex-

actly which features of OSNs users like and which

features users do not like and why.

Fig.2 shows the answers to Question 6. It shows

that 88% of respondents use OSNs daily, and 31.82%

of them are on OSNs constantly. This is not surpris-

ing considering all the respondents are users of OSNs.

On the other hand, it also suggest that any improve-

ment of OSN privacy protection mechanisms is likely

to have a positive impact on the daily life of many

OSN users.

4.3 User Attitude Towards On-line

Privacy

In this section, we user attitude towards on-line pri-

vacy in general based on the answers to our Question

8 on whether users are concerned about their privacy

when using OSNs and Question 9 on how much they

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

250

Figure 3: Answers to Question 8 “Do you concern about

your privacy while you use OSNs?”.

Figure 4: Answers to Question 10 “Have you read the pri-

vacy policy of your OSN?”.

are concerned.

Fig. 3 shows the answers to Question 8 grouped

by age groups. The result shows that almost 92%

respondents are concerned about their privacy while

using OSNs. An interesting observation is that the

percentage of respondents who concerns is higher by

about 10% in age groups between 21 and 35 than in

other age groups. We also found that while almost

100% of female respondents are concerned about

their privacy only about 85% of male respondents do.

From the answers to Question 9 (not shown here due

to page limit), we found that female respondents are

more concerned about their privacy than male respon-

dents, and respondents in age groups higher than 30

are more concern about their privacy than respondents

in younger age groups.

These results indicate the importance of improv-

ing users awareness of privacy, especially among

young male users.

4.4 User Knowledge About OSN

Privacy Policy

Every OSN publishes a privacy policy. It supposed

to inform users their privacy rights and the OSN’s re-

sponsibility of protecting user privacy. In this section

we analyze the answers to Question 10 on whether

Figure 5: Answers to Question 10 based on gender.

Figure 6: Answers to Question 11 “Are you satisfied with

the default privacy settings of your OSNs?”.

users have read their OSNs’ privacy policies. Accord-

ing to Fig. 4, 18% of the respondents have read their

privacy policy, 30% of respondents just read some

part of the privacy policy, and 52% of the respondents

did not read privacy policy. It is interesting that about

10% of respondents do not know about the existence

of the privacy policy or do not even care.

Fig. 5 shows the same answers based on gender.

It shows that 37% of female as opposed to 17% of

male respondents has read the privacy policies and

24% of female as opposed to 40% of male respon-

dents have not read the policies. This is consistent

with the answers to Questions 8 and 9 in Section 4.3,

which showed that female respondents are more con-

cerned about their on-line privacy than male respon-

dents.

4.5 Users Attitude Towards Default

Privacy Settings

In this section, we analyze answers to Question 11

on whether users are satisfied with their default pri-

vacy settings. Fig. 6 shows the answers to Question

11 by age groups. From this figure, less than 20%

of respondents across various age groups are satisfied

with their existing default privacy settings. The ma-

jority of respondents, more than 50% across all age

PrivacyandSecurityConcernofOnlineSocialNetworksfromUserPerspective

251

Figure 7: Answers to Question 12 “Do you agree for your

OSN to sell your personal information?”.

groups are somewhat satisfied. This result points to

an important area for OSNs to improve their services,

namely provide better default privacy settings. This is

especially important considering most users do con-

cern their privacy, yet are not really knowledgeable

what they should be to achieve a sufficient level of

privacy protection by themselves. Further research is

needed in this direction to gain more knowledge about

the specifics of the default settings that the majority

users like and dislike.

4.6 Users Attitude Towards Sharing

Their Information

In this section, we analyze answers to Questions 12 to

16, regarding who should be allowed to access their

private information. Information is an important in-

gredient for every individual. It can help to get insight

of particular person. Therefore, information has sig-

nificant impact on personal life. Small of portion of

information disclosure can lead our life towards big

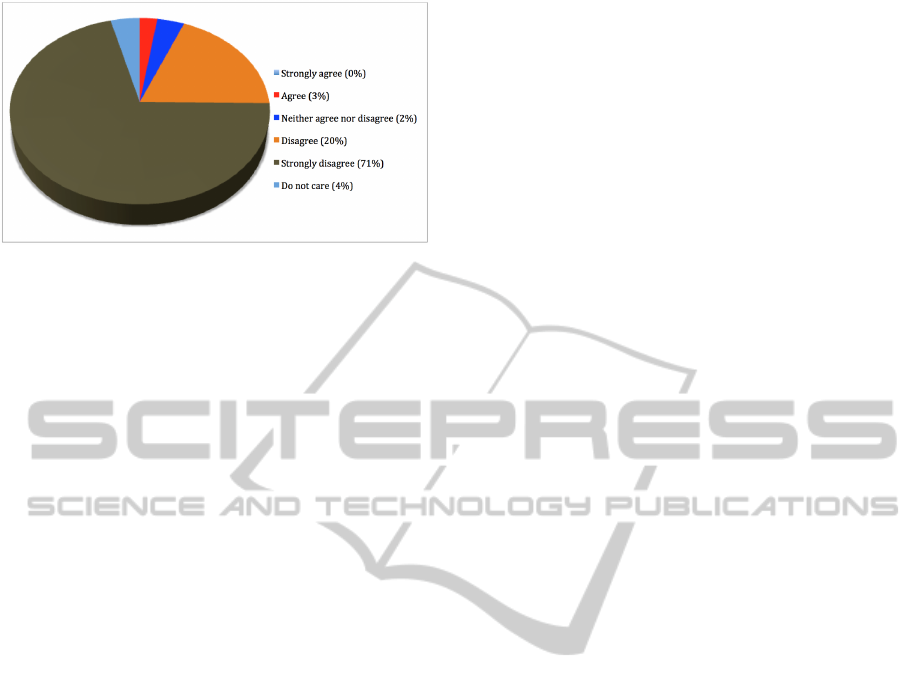

problem that has been discussed earlier. From Fig.7

shows the answers to Question 12. Based on this re-

sult, 71% of the respondents are strongly disagree for

OSNs to sell their personal information and 21% of

the respondents disagree. This brings up a crucial

point that in order for OSNs to meet user expecta-

tion about privacy protection, their privacy policies

and privacy protection mechanisms need to address

the issues of how to prevent the use of user informa-

tion that users do not endorse.

4.7 A Summary of the Results

According to our results, the majority of respondents

are concerned to a varying degree about their on-line

privacy, but not all of these users have read the privacy

policies of their OSNs. However, the vast majority of

respondents are against accessing their personal infor-

mation by ways that they could not control, say sell-

ing by OSNs or accessing by governments. In this re-

gard, majority of respondents are not totally satisfied

with their OSNs’ default privacy settings. To protect

user privacy, OSNs should pay more attention to user

attitude and enhance their privacy mechanisms espe-

cially the default privacy settings and novel methods

to counter internal threats. There is also a strong need

to educate users about on-line privacy, the privacy

policies of different OSNs, and the available privacy

mechanisms and how to use these mechanisms effec-

tively. Given the dynamics of OSNs, evolving tech-

nological aspects of privacy protection and privacy

breaching, future studies are also required to monitor

the user needs and feedback to OSN improvements.

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we present a study of online OSNs pri-

vacy from a user perspective. We designed a set of

questions aimed to learn about user views of online

privacy, user knowledge about OSNs privacy settings,

and user awareness of privacy disclosure. Our goal

is to find out whether and how well users are knowl-

edgable of, satisfied with, and able to effectively use

available privacy settings. We collected answers from

a group of 377 users, selected via several methods,

who have experiences with multiple OSNs, including

Facebook, Google+, and LinkedIn. Our study shows

that 44% of the users lack the knowledge about pri-

vacy policies and mechanisms of their OSNs, 34%

and 41% of the users, respectively, are seriously and

somewhat concern about their privacy protection, and

80% of the users do not think their OSNs have pro-

vided sufficient privacy control or default privacy set-

tings that match their expectations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the annonymous re-

viewers of this paper for their constructive comments

and the CS department of UTSA for support of the

first author.

REFERENCES

Global publics embrace social networking. pewresearch-

center, 08/03/2014.

Beato, F. and Peeters, R. (2014). Collaborative joint content

sharing for online social networks. In IEEE Interna-

tional Workshop on Pervasive Computing and Com-

munications.

ICISSP2015-1stInternationalConferenceonInformationSystemsSecurityandPrivacy

252

Boshmaf, Yazan, e. a. (2011). The socialbot network: when

bots socialize for fame and money. In Proceedings of

the ACM 27th Annual Computer Security Applications

Conference.

Fang, L. and LeFevre, K. (2010). Privacy wizards for so-

cial networking sites. In Proceedings of the ACM 19th

international conference on World wide web.

HongxinHu, Ahn, G.-J., and Jorgensen, J. (2012). Enabling

collaborative data sharing in google+. In IEEE Global

Communications Conference (GLOBECOM).

Johnson, M., Egelman, S., and Bellovin, S. M. (2012).

Facebook and privacy: it’s complicated. In Proceed-

ings of the ACM eighth symposium on usable privacy

and security.

Krishnamurthy, B. and Wills, C. E. (2008). Characterizing

privacy in online social networks. In Proceedings of

the ACM First Workshop on Online Social Networks.

Lappas, Theodoros, e. a. (2010). Finding effectors in social

networks. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGKDD

international conference on Knowledge discovery and

data mining.

Lappas, T., Liu, K., and Terzi, E. (2009). Finding a team of

experts in social networks. In Proceedings of the 15th

ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowl-

edge discovery and data mining.

Liu, Yabing, e. a. (2011). Analyzing facebook privacy set-

tings: user expectations vs. reality. In Proceedings

of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM conference on Internet

measurement.

Madejski, M., Johnson, M., and Bellovin, S. M. (2012). A

study of privacy settings errors in an online social net-

work. In IEEE International Workshop on Pervasive

Computing and Communications.

Michael Fire, e. a. (2012). Social privacy protector-

protecting users’ privacy in social networks. In

the second international conference on social eco-

informatics SOTICS.

Miltgen, C. L. and Peyrat-Guillard, D. (2014). Cultural and

generational influences on privacy concerns: a qual-

itative study in seven european countries. European

Journal of Information Systems, 23(2):103–125.

Netter, Michel, e. a. (2013). Privacy settings in online so-

cial networks–preferences, perception, and reality. In

The 46th IEEE Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences (HICSS).

Pagoto, S. L., Schneider, K. L., Oleski, J., Smith, B., and

Bauman, M. (2014). The adoption and spread of

a core-strengthening exercise through an online so-

cial network. Journal of physical activity & health,

11(3):648–653.

Park, J. S., Kwiat, K. A., Kamhoua, C. A., White, J., and

Kim, S. (2014). Trusted online social network (osn)

services with optimal data management. Computers

& Security, 42:116–136.

Tucker, C. (2014). Social networks, personalized advertis-

ing and privacy controls. Journal of Marketing Re-

search.

Xiao, X. and Tao, Y. (2006). Personalized privacy preser-

vation. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM SIGMOD

international conference on Management of data.

PrivacyandSecurityConcernofOnlineSocialNetworksfromUserPerspective

253