Modelling the Resistance of Enterprise Architecture Adoption

Linking Strategic Level of Enterprise Architecture to Organisational Changes and

Change Resistance

Nestori Syynimaa

1,2,3,4

1

Informatics Research Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading, Reading, U.K.

2

School of Information Sciences, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

3

Enterprise Architect, CSC - IT Center for Science, Espoo, Finland

4

Founder, Gerenios Ltd, Tampere, Finland

Keywords: Enterprise Architecture, Adoption, Change Resistance, Strategic Level.

Abstract: During the last few years Enterprise Architecture (EA) has received increasing attention among industry and

academia. By adopting EA, organisations may gain a number of benefits such as better decision making,

increased revenues and cost reduction, and alignment of business and IT. However, EA adoption has been

found to be difficult. In this paper a model to explain resistance during EA adoption process (REAP) is

introduced and validated. The model reveals relationships between strategic level of EA, resulting

organisational changes, and sources of resistance. By utilising REAP model, organisations may anticipate and

prepare for the organisational change resistance during EA adoption.

1 INTRODUCTION

During the last few years Enterprise Architecture

(EA) has received increasing attention among

industry and academia. An effective EA is critical to

business survival and success (TOGAF, 2009).

Indeed, in 21

st

century EA will be determining factor

that separates the successful from the failures, the

survivors from the others (Zachman, 1997). EA has

some important strategic outcomes, such as better

operational excellence and strategic agility (Ross et

al., 2006). Despite the benefits to be gained, EA is not

widely adopted in organisations (Schekkerman, 2005;

Ambler, 2010; Computer Economics, 2014). This

might be caused by the fact that EA has been found

difficult to adopt. From theoretical point of view, EA

adoption is an instance of organisational change

aiming for realisation of EA benefits. However, about

70 per cent of organisational change initiatives fail

(Hammer and Champy, 1993; Beer and Nohria, 2000;

Kotter, 2008).

This study aims for increase the understanding of

the dynamics of EA adoption. To be more specific,

we are seeking an answer to the question: Why is

Enterprise Architecture difficult to adopt?

1.1 Definition of Enterprise

Architecture

Enterprise Architecture (EA) has multiple definitions

in the current literature. The concept of Enterprise

Architecture consists of two distinct terms, enterprise

and architecture.

Definition of enterprise seems to be quite constant

in the EA literature. Enterprise can be anything from

a local team to a multi-level organisation of a global

corporation (TOGAF, 2009; ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2011;

Dietz et al., 2013; PEAF, 2013). It is a social system

with an assumed purpose (Proper, 2013; Dietz et al.,

2013) having a common set of goals (TOGAF, 2009).

As the term enterprise is usually used as a synonym

of a business or company, later in this paper we will

use the term organisation instead of it. Organisation

covers both businesses and public sector and thus

suits better to be used in this paper.

Similarly, definitions of architecture and

architecture description are more or less constant.

Architecture is a structure of the enterprise and an

architecture description its representation

(ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2011). To be more specific,

architecture is seen as a formal description of an

enterprise at a certain time (Zachman, 1997; TOGAF,

143

Syynimaa N..

Modelling the Resistance of Enterprise Architecture Adoption - Linking Strategic Level of Enterprise Architecture to Organisational Changes and Change

Resistance.

DOI: 10.5220/0005349901430153

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 143-153

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2009; ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2011), either from the current

state or from one or more future states (CIO Council,

2001; Gartner, 2013).

Definitions of Enterprise Architecture are more

diverse, but they also have some similarities. What is

shared among most of the definitions is the concept

of managed change of the enterprise between the

current and future states for a purpose (GERAM,

1999; CIO Council, 2001; Pulkkinen, 2008; Gartner,

2013). According to EA specialists, this purpose is to

meet goals of stakeholders and to create value to the

enterprise (Syynimaa, 2010, see also PEAF, 2010).

Aforementioned definitions can be summarised to

the following definition used in this paper. Enterprise

Architecture is; (i) a formal description of the current

and future state(s) of an organisation, and (ii) a

managed change between these states to meet

organisation’s stakeholders’ goals and to create value

to the organisation.

1.2 Enterprise Architecture Adoption

The word adoption can be defined as “the action or

fact of adopting or being adopted” where adopt refers

to "choose to take up or follow (an idea, method, or

course of action)" (Oxford Dictionaries, 2010).

Similar concepts are implementation, “the process of

putting a decision or plan into effect; execution”

(ibid.) and institutionalisation, which is to “establish

(something, typically a practice or activity) as a

convention or norm in an organization or culture”

(ibid.). Following these definitions, in the EA context

adoption can be defined as the process where

organisation starts using EA methods and tools for the

very first time.

As a consequence, EA adoption is causing

changes to the organisation. The organisation is

adopting a new way to communicate (to describe) its

current and future states, and a new formal way to

develop the organisation to achieve its stakeholders’

goals. Thus, we will adopt organisational change as

the underpinning theory to explain EA adoption.

As noted earlier, organisations can be categorised

as systems. Lee (2010) states that systems may evolve

from one state to another deliberately by design, or in

a natural uninformed way (the default). Van de Ven

and Poole (1995) have recognised four ideal-types

organisational development theories to explain

organisational change processes (Figure 1). These are

Life Cycle, Evolution, Dialectic, and Teleology. Life

Cycle theory sees change being imminent;

organisation is moving from a start-up towards its

termination through certain phases. Each of these

phases is necessary, so the change is following always

the same steps. Environment may influence this

change, but it is not a driving force. Teleological

theory sees that the change takes place because the

organisation is trying to achieve a certain goal or

purpose. Although this theory is also cyclical,

fundamental difference is that there is no certain

sequence of events to be followed. Moreover, the or-

Figure 1: Process Theories of Organisational Development and Change (Van de Ven and Poole, 1995).

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

144

ganisations do not “terminate”, but are changing

indefinitely. Dialectical theory assumes that

organisation exist in world of continuous conflicts.

The change takes place when two or more opposing

forces gain power enough to confront the status quo.

Evolutionary theory sees change as a method to

survive; competing from the same resources causes

elimination of some of the organisations.

The most used theories in the current change

management literature are life cycle and teleological

theory (Van de Ven and Poole, 1995; Kezar, 2001). It

can be argued that the latter one, teleological theory,

explains the best EA adoption. First of all, EA is

adopted in a single entity: an organisation. Secondly,

EA adoption is constructive, as it is aiming to a

specific goal e.g. EA adoption.

According to Csribra and Gergely (2007) there are

two ways to predict future events in teleological

change via goal attribution. These are an action-to-

goal and goal-to-action. The former can be

interpreted as a question: What is the function of EA

adoption? In the same way the latter can be

interpreted as a question: What action should be taken

to achieve EA being adopted? A summary of

differences of these two interpretation action can be

seen in Table 1.

Table 1: The Functions of Teleological Interpretation of

Actions (Csibra and Gergely, 2007).

Primary

function

Type of inference

‘Action-to-Goal’ ‘Goal-to-Action’

On-line

Prediction

Goal prediction:

Predicting the likely

effect of an on-

going action

Action anticipation:

Predictive tracking of

dynamic actions in

real time

Social

Learning

Discovering novel

goals and artefact

functions

Acquiring novel

means actions by

evaluating their causal

efficacy in bringing

about the goal

EA adoption can be of both types. If the

organisation has a problem it tries to solve with EA

adoption, it would be action-to-goal type; function of

EA adoption is to solve the problem. If, on the other

hand, organisation’s goal is to adopt EA, it would be

goal-to-action type. In this research we are interested

in which actions are taken while adopting EA so the

type of inference is goal-to-action.

Another dimension of predicting future events in

teleological change is the primary function of the

prediction (Csibra and Gergely, 2007). There are two

functions, on-line prediction and social learning. The

former is aiming for prediction of either the goal or

action based on ongoing actions. The latter aims to

learning and finding of novel goals or means actions.

In this paper, we are interested in increasing the

understanding of the EA adoption so the primary

function is social learning.

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In order to model Enterprise Architecture adoption,

the literature related to EA and organisational change

was reviewed. Based on the literature review, an EA

adoption model was formed to explain the resistance

during EA adoption.

Model’s validity is a primary measure of its utility

and effectiveness (Groesser and Schwaninger, 2012).

Therefore its validity needs to be tested using an

appropriate validation method. Our model contains

merely causal relationships and can therefore be

validated using structure verification tests (Barlas,

1996). For instance in a major behaviour patterns

test, the model’s accuracy to reproduce real-life

behaviour is tested (Barlas, 1996).

Our model is validated against empirical data

acquired from a real-life EA-pilot. The validation is

performed by analysing the empirical data using a

directed content analysis approach. This approach is

similar to the Grounded Theory approach by Strauss

and Corbin (1990). The major difference is that the

codes and keywords are derived from theory or from

relevant research findings instead of data (Hsieh and

Shannon, 2005). Therefore the validity of our model

can be tested by analysing data by using the model as

a source for codes and keywords.

3 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

ADOPTION MODEL

In this section we will describe the formulation of our

conceptual model of EA adoption. First the three

individual components of the model are introduced.

The first component, the strategic level of Enterprise

Architecture, is based on a selected Enterprise

Architecture literature. Second and third components,

organisational change and change resistance,

respectively, are adopted from general organisational

change literature. After introduction of the

components, the conceptual model of EA adoption is

presented.

3.1 Strategic Level of Enterprise

Architecture

Enterprise Architecture is a relatively new phenome-

ModellingtheResistanceofEnterpriseArchitectureAdoption-LinkingStrategicLevelofEnterpriseArchitectureto

OrganisationalChangesandChangeResistance

145

Figure 2: Antecedents, Explicit Reactions, and Change Consequences of Organisational Change (Oreg et al., 2011).

non, having a multiple schools of thought. Lapalme

(2011, 2012) has recognised three ideal schools from

the current EA literature; Enterprise IT Architecting,

Enterprise Integrating, and Enterprise Ecological

Adaption.

Enterprise IT Architecting school is aiming to

alignment of organisation’s IT assets and business

activities. The school often describes EA as “the glue

between business and IT” (Lapalme, 2012, p. 38).

From a strategic point of view, EA is merely a tool to

fulfil business objectives without questioning them in

any way.

The goal of Enterprise Integrating school is to

execute organisation’s strategy by maximising

organisation’s coherency. Thus the school views EA

as “the link between strategy and execution” (ibid.,

2012, p. 40).

For Enterprise Ecological Adaptation school EA

means designing all organisational facets, including

bidirectional relationship to its environment. This

school is interested also in what is happening outside

of organisation’s borders, and is actively trying to

change also the surrounding environment. Thus EA is

described to be “the means for organisational

innovation and sustainability” (ibid., 2012, p. 41).

Each of the three EA schools of thought can be

seen being on a different strategic level. At the lowest

level, EA is used merely as the glue between business

and IT. On higher levels, EA is seen more as a means

to executing organisation’s strategy, but also as way

to systemically change the environment of the

organisation.

Strategic level decisions and choises are affecting

the whole organisation. Organisations may take

different tactical stance to achieve their strategy

(Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010). This means

that strategic decisions likely causes more changes

than the tactical ones. As such, it can be argued that

the higher the strategic level of EA, the more changes

the organisation will face during the EA adoption.

3.2 Organisational Changes

Oreg et al., (2011) have formed a model of change

recipient actions (Figure 2) based on a literature

review of 79 quantitative organisational change

studies between 1948 and 2007. Their model suggests

that change and pre-change antecedents are linked to

individual’s explicit reactions and change

consequences. Also explicit reactions are linked to

change consequences. This model gives us a good

starting point for our model of EA adoption. As noted

Traits; Coping styles; Needs;

Demographics

Antecedent

s

Pre-Change Antecedents

Change Recipient Characteristics

Supportive environment and trust;

Commitment; Culture; Job

characteristics

Internal Context

Participation; Communication and

info; Interactional and procedural

justice; Principal Support;

Management competence

Change Antecedents

Change Process

Anticipated outcomes; Job

insecurity; Distributive justice

Perceived Benefit/Harm

Compensation; Job design; Office

layout; Shift schedule

Change Content

Affective reaction

Negative, e.g., Stress

Positive, e.g., Pleasantness

Explicit Reactions

Cognitive reaction

Change evaluation

Change beliefs

Behavioral reaction

Change recipient

involvement

Behavioral intentions

Coping behaviors

Change consequences

Job satisfacetion

Org. Commitment

Performance

Work-Related

Consequences

Well-being

Health

Withdrawal

Personal Consequences

Traits; Coping styles; Needs;

Demographics

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

146

earlier, EA adoption is an instance of teleological

organisational change. Therefore it can be assumed

that pre-change and change antecedents will result in

organisational and personal consequences, either

directly or indirectly by explicit reactions, also in EA

adoption.

Organisational changes can be categorised to four

types (Cao et al., 2000; 2003). These types of

organisational change are; (i) changes in processes,

(ii) changes in functions (structural change), (iii)

changes in power within the organisation (political

change), and (iv) changes in values (cultural change).

This categorisation gives us a tool for classifying

anticipated consequences and results caused by EA

adoption.

3.3 Change Resistance

Every change, no matter how big or small, will face

resistance. However, the higher the impact of the

change the higher is the resistance (Bovey and Hede,

2001). Change resistance can be defined as “any

phenomenon that hinders the process at its beginning

or its development, aiming to keep the current

situation” (Pardo del Val and Martinez Fuentes, 2003,

p. 152). Following this definition, resistance during

EA adoption refers to any phenomenon hindering the

adoption. Resistance can be intentional or

unintentional, can be recognised by target, or can be

recognised by observer (Hollander and Einwohner,

2004). Another concept closely related to resistance

is inertia, which can be defined as “a tendency to do

nothing or to remain unchanged” (Oxford

Dictionaries, 2010). In other words, for some reason,

organisation resists changing the status quo of the

organisation. One example of inertia is a structural

inertia, which “refers to a correspondence between

the behavioural capabilities of a class of organizations

and their environments” (Hannan and Freeman, 1984,

p. 151). In the other words, the organisation has high

structural inertia when the speed of reorganisation is

lower than the speed of environmental conditions

change. In our EA adoption model, conceptually we

do not make difference between change resistance

and inertia.

Pardo del Val and Martinez Fuentes (2003) have

recognised two types of resistance related to

organisational change; inertia during the planning

stage, and inertia in the execution stage. Reasons

behind the former type of inertia are (i) distorted

perception, interpretation barriers and vague strategic

priorities, (ii) low motivation, and (iii) lack of

creative response. Reasons behind the latter type of

inertia are (iv) political and cultural deadlocks, and

(v) other reasons. In the context of EA adoption,

resistance can occur during the planning stage of the

adoption and during its execution. Complete list of

sources of resistance in the planning and execution

stages can be seen in Table 3 and Table 2,

respectively.

Table 2: Sources of Change Resistance During the

Execution (adapted from Pardo del Val and Martinez

Fuentes, 2003).

Category Source of Resistance

Political and

Cultural

Deadlocks

Implementation climate and relation between

change values and organisational values,

Departmental politics,

Incommensurable beliefs,

Deep rooted values,

Forgetfulness of the social dimension of

changes.

Other

Sources

Leadership inaction,

Embedded routines,

Collective action problems,

Capabilities gap,

Cynicism.

Table 3: Sources of Change Resistance During the Planning

(adapted from Pardo del Val and Martinez Fuentes, 2003).

Category Source of Resistance

Distorted

Perception

Myopia,

Denial,

Perpetuation of ideas,

Implicit assumptions,

Communication barriers,

Organisational silence.

Low

Motivation

Direct costs of charge,

Cannibalisation costs,

Cross subsidy comforts,

Past failures,

Different interests among employees and

management.

Lack of

Creative

Response

Fast and complex environmental changes,

Resignation,

Inadequate strategic vision.

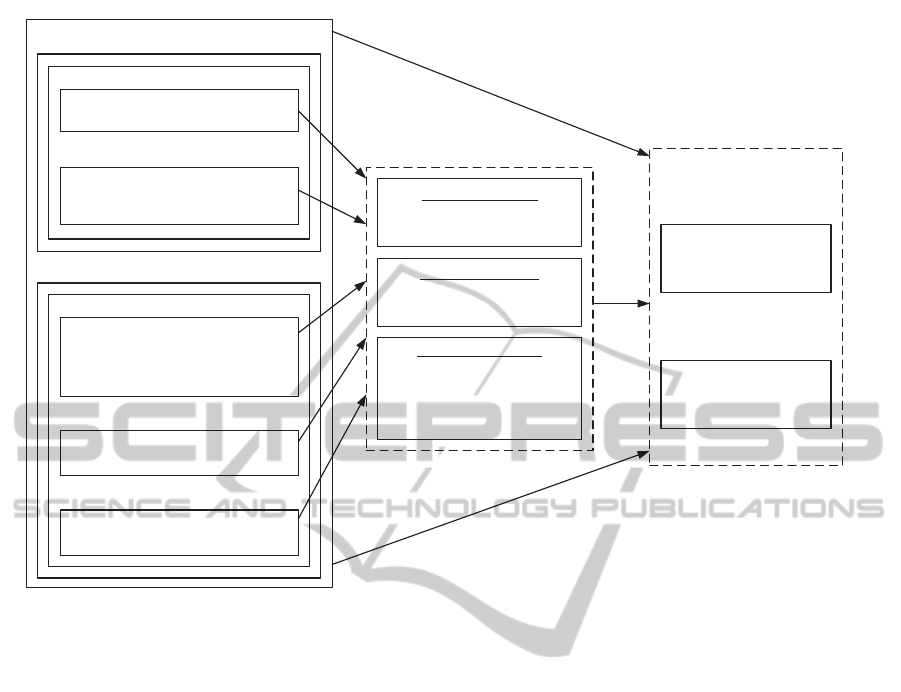

3.4 EA Adoption Model

The conceptual model of Resistance in EA adoption

Process (REAP) can be seen in Figure 3. The model

is based on the EA and organisational change

literature. Logical reasoning of the model is as

follows. Enterprise Architecture can be used on

different strategic levels (Lapalme, 2012). The

selected strategic level sets boundaries to EA

adoption, e.g. what kind of objectives are set for the

adoption and thus what kind of organisational

changes may result (Cao et al., 2003). In other words,

the strategic level of EA influences the objectives of

the adoption. These objectives (change antecedents)

are influencing the resulting changes directly and

indirectly via explicit reactions of people (Oreg et al.,

ModellingtheResistanceofEnterpriseArchitectureAdoption-LinkingStrategicLevelofEnterpriseArchitectureto

OrganisationalChangesandChangeResistance

147

Figure 3: Conceptual Model of Resistance in EA Adoption Process (REAP).

2011). During the planning and execution phases of

the adoption, organisational resistance (reactions of

people) may distort adoption and thus influences the

outcomes of the adoption (Pardo del Val and

Martinez Fuentes, 2003).

3.5 Validation

3.5.1 Enterprise Architecture Pilot

In this sub-section our model is validated using

empirical data collected from a real-life EA pilot (see

CSC, 2011). The EA pilot was conducted in 2010

among 12 Finnish Higher Education Institutions

(HEIs), which of two merged in the beginning of the

pilot. During the pilot, EA was adopted by

participating HEIs.

Demographic data collected from the public

websites of the participating institutions can be seen

in Table 4. Pilot participants represented 29 % of

Finnish HEIs. Nine of the participating institutions

were Universities of Applied Sciences (formerly

known as Polytechnics) and two Universities.

Table 4: Pilot Institutions.

HEI Students Employees Location

1 8 100 800 Southern Finland

2 2 000 200 Northern Finland

3 2 900 300 Northern Finland

4 5 200 400 Southern Finland

5 4 800 600 Northern Finland

6 7 500 600 Southern Finland

7 16 000 1 200 Southern Finland

8 4 800 400 Western Finland

9 3 000 300 Northern Finland

10 15 900 2 900 Northern Finland

11 10 000 800 Southern Finland

HEIs were organised to six groups each focusing

to a certain problem domain. These groups were

Education, Adult Education, Merger, Consortium,

Quality Assurance, and Network. Quality Assurance

(QA) and Adult Education (AE) sub-projects were

merged during the pilot.

Table 5: Pilot Groups.

Group Institution(s)

Network 1, 4, 6

Education 7

Consortium 3, 5, 9

Merger 11 (12)

QA & AE 2, 8, 10

3.5.2 Data Collection

The data was collected using semi-structured

interviews as a part of a PhD research. Themes for the

interviews were derived from the factors affecting EA

adoption. These factors were identified from the

literature during a Systematic Literature Review

conducted following the instructions by Kitchenham

(2007). The review included 35 studies on EA

adoption. Identified factors were categorised under

three categories; Organisational factors, such as

organisational capabilities, EA related factors, such

as EA specific skills, and environmental (contextual)

factors, such as possible external pressure. Following

instructions by Kvale (1996), questions seen in Table

were formed for interviews.

Interviews were performed between June and

October 2010 by phone and were recorded for

transcribing. Total number of 22 individuals were

interviewed from three different roles; CIOs, rectors

(principals), and Quality Assurance staff.

Strategic level of

Enterprise Architecture

Objectives

(desired changes)

Resistance during

planning

Enterprise Ecological

Adaptation

Enterprise Integrating

Enterprise IT

Architecting

Cultural

Political

Structural

Process

Outcomes

(r es u ltin g c han g e s)

Cultural

Political

Structural

Process

Distorted Perception

Low Motivation

Lack of creative

response

Resistance during

execution

Political and Cultural

Deadlocks

Other Reasons

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

148

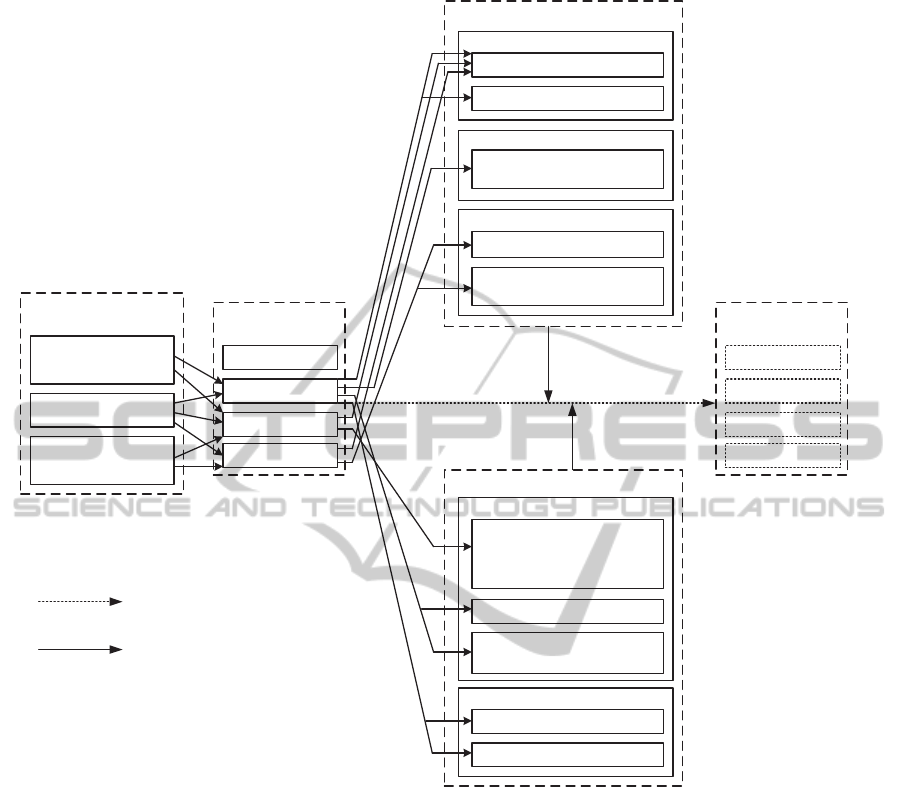

Figure 4: Group Level Analysis.

3.5.3 Data Coding

Coding was performed using NVivo software

package; Version 9.2.81.0 (64-bit). Transcriptions of

the interviews were automatically organised as nodes

using NVivo’s Auto code feature so that each

question formed a node. Each of these nodes

contained all answers for the particular question from

all interviews.

Table 6: Interview Questions.

Think about some major change(s) your organisation have

faced during the past few years. Describe such a change and

how it was conducted. Which challenges, if any, the change

faced.

Describe the process how new information systems are

defined, acquired or implemented, and introduced in your

organisation.

Describe how new development initiatives are introduced in

your organisation. Who or which party is driving such

initiatives? How important this is for the success of the

initiative?

Describe on what basis are development initiatives given

resources in your organisation.

Describe how EA is organised in your organisation.

Describe how communication is organised in your

organisation. How about between external stakeholders?

About EA pilot, explain what are your or your organisation's

expectations for the pilot. How are they related to your

organisation's strategy?

Which kind of expectations from other stakeholders have you

faced/know?

Explain how EA pilot or similar initiatives are related to the

government level programs. How are such programs

coordinated? What are the power relationships in such

coordination?

Table 6: Interview Questions (cont.).

Tell me about EA pilot, explain how was the used framework

selected? Does the framework require any modification to suit

your purposes? Explain. On which kind of principles is the EA

pilot based on? Explain in your own words EA and related

terms.

Explain your and your organisation's EA experience. Has there

been any training during the pilot? Which parts of EA, if any,

you think your organisation has most challenges? Have you

used contracted specialists/consultants during the pilot?

Table 7: Categories Used in Analysis.

Main category and source Sub-categories

Strategic level of EA

(Lapalme, 2012)

Enterprise IT Architecting,

Enterprise Integrating,

Enterprise Ecological

Adaptation.

Objectives

(Cao et al., 2003)

Processes, Structural,

Cultural,

Political.

Resistance during planning

(Pardo del Val and Martinez

Fuentes, 2003)

Distorted perception, Vague

strategic priorities,

Low motivation,

Lack of creative response.

Resistance during execution

(Pardo del Val and Martinez

Fuentes, 2003)

Political and cultural

deadlocks,

Other reasons.

The actual coding of each node followed the same

process. Each answer were coded by searching for

occurences of the codes listed in Table 7 First each

answer was analysed from the strategic level of EA

point-of-view, next from changes point-of-view, and

finally from the resistance point-of-view.

AD

Network

IN

AR

CU

PO

ST

PR

DI

LO

LA

DE

OT

AD

Education

IN

AR

CU

PO

ST

PR

DI

LO

LA

DE

OT

AD

Consortium

IN

AR

CU

PO

ST

PR

DI

LO

LA

DE

OT

AD

Merger

IN

AR

CU

PO

ST

PR

DI

LO

LA

DE

OT

AD

QA & AE

IN

AR

CU

PO

ST

PR

DI

LO

LA

DE

OT

Legend:

This pilot with link

This pilot without a link

Previous change(s) with a link

Previous change(s) with a link

Interpreted from capabilities

Link

ModellingtheResistanceofEnterpriseArchitectureAdoption-LinkingStrategicLevelofEnterpriseArchitectureto

OrganisationalChangesandChangeResistance

149

4 RESULTS

Illustrated summary of analysis on the group level can

be seen in Figure 4, where the analysis of each group

(see Table 5) are combined to a single diagram. Boxes

on the left represents strategic levels of EA, boxes in

the middle the types of organisational change, and

boxes on the right categories of sources of resistance.

The legend for used abbreviations can be seen in

Table 8.

Black and white circles represents findings from

the analysis of the questions related to the goals and

objectives of the EA pilot. A white circle indicates that

the particular concept is found from the data. Solid

black dot indicates that it is found from the data and

linked to another finding. For instance in the Network

group it can be seen that there is evidence in the data

suggesting that the level of EA is seen as Enterprise

Integrating. However, the same respondent has not

mentioned any particular change, so there is nothing

it could be linked to. It can also be noted that there is

a link between Enterprise IT Architecting and

Process change. In this case, the respondent has

expressed both the strategic level of EA, and the

actual change to be achieved. In some cases, such as

in the Network group, there is also a link between the

change and a source of resistance, supported by the

data. Black and white squares represents findings

from the analysis of the questions related to past

changes and challenges, and diamonds to possible

sources of resistance interpreted from answers.

Table 8: Abbreviations of Categories Used in Analysis.

Strategic level Change type Resistance

AD

Enterprise

Ecological

Adaptation

CU Cultural DI

Distorted

Perception

IN

Enterprise

Integrating

PO Political LO

Low

Motivation

AR

Enterprise IT

Architecting

ST Structural LA

Lack of

Creative

response

PR Process DE

Political and

Cultural

Deadlocks

OT

Other

Reasons

The summary of the findings is illustrated in

Figure 5. Dotted arrows indicates logically deduced

influence, as described in the REAP. Solid arrows, in

turn, indicate empirically validated influence.

Next we will briefly explain and discuss results in

textual form. As suggested by REAP model, all

strategic levels of EA were present in the data.

However, there were no evidence of the adoption

aiming for cultural changes of the organisation.

Therefore Cultural change was removed from the

results. One possible explanation for this is that as EA

is used for the very first time, it is “safer” to focus on

easier changes first. After all, as it can be seen in

Figure 4, previous cultural changes in organisations

have caused resistance in four out of five resistance

categories, as has political changes.

Sources of resistance were found in all five

categories, as suggested by the REAP model.

However, only 10 out of 24 sources were found from

the data. This leaves 14 sources of resistance (see

Table 3 and Table 2) which were not faced in the EA

pilot. One explanation for this is that such sources of

resistance might not been faced in Finnish HEIs at all.

More likely explanation is that those sources of

resistance were not met in this particular pilot but

would likely be faced in other settings. For instance

during the executing of cultural changes, political and

cultural deadlocks are most likely faced. As noted

earlier, there were no cultural changes executed nor

planned during the EA-pilot.

The REAP model is a qualitative model, e.g. it

captures the resistance emerging from the data, but

does not judge any source of resistance being more

important than other. However, it should be noted that

most of the resistance faced during the planning phase

of the EA-pilot were related to understanding of EA

concepts (Distorted Perception). Other studies have

also noticed the lack of EA knowledge in the Finnish

public sector. For instance Lemmetti and Pekkola

(2012) argues that current definitions of EA are

inconsistent and thus confusing both researchers and

practitioners. This is also supported by Hiekkanen et

al., (2013); EA is underutilised due to lack of

understanding it properly. In general, poor

communication have been found to be one of the

factors contributing to EA adoption failures

(Mezzanotte et al., 2010). Moreover, value of EA is

directly influenced by how EA is understood in the

organisation (Nassiff, 2012).

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we formed a model to explain the

process of Enterprise Architecture (EA) adoption. A

teleological organisational change was adopted as an

underpinning theoretical view to EA adoption. The

model of resistance during EA adoption process

(REAP) was formed based on the literature. Our

model revealed previously unexplored relationships

between the strategic level of EA and objectives of

EA adoption. Also relationships between these

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

150

Figure 5: Results of Data Analysis.

objectives and various sources of organisational

resistance were identified.

As it can be interpreted from the analysis, the

REAP model can be used to categorise the adoption

process. Moreover, as stated by Barlas and Carpenter

(1990) a valid model can be assumed to be one of the

many possible ways to describe a real world. Thus it

can be argued that the model is valid in this context,

e.g. it does reproduce real life behaviour found from

the EA-pilot.

5.1 Implications

The results of this study have implications to both

science and practice. For science, REAP model

provides a model to explain the organisational

resistance during the EA adoption. We have

demonstrated that the resistance depends on the

changes the EA adoption is causing. As such, it

contributes to the organisational science.

For the practice, the REAP model provides a tool

which can be used to anticipate possible sources of

resistance. When the relationships between the

strategic level of EA, resulting changes, and sources

of resistance are known, one can prepare for and

minimise the resistance during the adoption.

5.2 Limitations and Future Work

The empirical data used to validate the model was

gathered from an EA pilot conducted among 12

Finnish Higher Education Institutions. This limits the

generalisability of the results as such a qualitative

data is contextually-bound. However, similar

Objectives

(desired changes)

Cultural

Poli tical

Structural

Process

Strategic level of

Enterprise Architecture

Resistance during planning

Enterprise Ecological

Adaptation

Enterprise Integrating

Enterprise IT

Architecting

Outc omes

(resulting changes)

Cultural

Political

Structural

Process

Distorted Perception

Low Motivation

Resistance during execution

Communication barriers

Perpetuation of ideas

Different interests among

employees and management

Lack of creative response

Inadequate strategic vision

Fast and complex

environmental change

Political and Cultural Deadlocks

Implementation climate and

relation between change

values and organisational

values

Forgetfulness of the social

dimension of changes

Other

Capabilities gap

Cynicism

Departmental politics

Logically deduced

influence

Empirically validated

influence

ModellingtheResistanceofEnterpriseArchitectureAdoption-LinkingStrategicLevelofEnterpriseArchitectureto

OrganisationalChangesandChangeResistance

151

challenges have been found also from other settings

(Kaisler et al., 2005; Pehkonen, 2013; Seppänen,

2014) which supports our findings. REAP is based on

general non-HEI-specific literature, and therefore it is

likely explaining resistance during EA adoption also

in a wider context. Therefore we are encouraging

researchers and practitioners to apply REAP model in

other settings to increase its validity and

generalisability.

Author acknowledges that the REAP model is one

possible way to describe EA adoption. This means

that REAP is not necessarily comprehensive, i.e.

there may be sources of resistance that are not

captured by the model. Therefore we are encouraging

researchers also to improve the model.

Analysing the empirical data with the REAP

model revealed that most of the planning phase

resistance was caused by the lack understanding EA

knowledge. Thus one direction for the future research

could be finding ways to overcome this type of

resistance.

REFERENCES

Ambler, S. 2010. Enterprise Architecture Survey Results:

State of the IT Union Survey [Online]. Available:

http://www.ambysoft.com/surveys/stateOfITUnion201

001.html [Accessed Jan 21

st

2015].

Barlas, Y. 1996. Formal aspects of model validity and

validation in system dynamics. System Dynamics

Review, 12, 183-210.

Barlas, Y. & Carpenter, S. 1990. Philosophical roots of

model validation: two paradigms. System Dynamics

Review, 6, 148-166.

Beer, M. & Nohria, N. 2000. Cracking the code of change.

Harvard Business Review, 78, 133-141.

Bovey, W. H. & Hede, A. 2001. Resistance to

organizational change: the role of cognitive and

affective processes. Leadership & Organization

Development Journal, 22, 372-382.

Cao, G., Clarke, S. & Lehaney, B. 2000. A systemic view

of organisational change and TQM. The TQM

Magazine, 12, 186-193.

Cao, G., Clarke, S. & Lehaney, B. 2003. Diversity

management in organizational change: towards a

systemic framework. Systems Research and Behavioral

Science, 20, 231-242.

Casadesus-Masanell, R. & Ricart, J. E. 2010. From strategy

to business models and onto tactics. Long range

planning, 43, 195-215.

CIO Council 2001. A Practical Guide to Federal Enterprise

Architecture. Available at

http://www.cio.gov/documents/bpeaguide.pdf.

Computer Economics. 2014. Enterprise Architecture

Adoption and Best Practices. April 2014. [Online].

Available:

http://www.computereconomics.com/article.cfm?id=1

947 [Accessed Jan 21

st

2015].

CSC. 2011. Kokonaisarkkitehtuuri eli KA-pilotti [Online].

Available: http://raketti.csc.fi/kokoa/pilotti [Accessed

May 30

th

2011].

Csibra, G. & Gergely, G. 2007. ‘Obsessed with goals’:

Functions and mechanisms of teleological

interpretation of actions in humans. Acta Psychologica,

124, 60-78.

Dietz, J. L. G., Hoogervorst, J. A. P., Albani, A., Aveiro,

D., Babkin, E., Barjis, J., Caetano, A., Huysmans, P.,

Iijima, J., van Kervel, S. J. H., Mulder, H., Op ‘t Land,

M., Proper, H. A., Sanz, J., Terlouw, L., Tribolet, J.,

Verelst, J. & Winter, R. 2013. The discipline of

enterprise engineering. Int. J. Organisational Design

and Engineering, 3, 86-114.

Gartner. 2013. IT Glossary: Enterprise Architecture (EA)

[Online]. Available: http://www.gartner.com/it-

glossary/enterprise-architecture-ea/ [Accessed Feb 21

st

2013].

GERAM 1999. GERAM: Generalised Enterprise

Reference Architecture and Methodology. Version

1.6.3. IFIP-IFAC Task Force on Architectures for

Enterprise Integration. IFIP-IFAC Task Force.

Groesser, S. N. & Schwaninger, M. 2012. Contributions to

model validation: hierarchy, process, and cessation.

System dynamics review, 28, 157-181.

Hammer, M. & Champy, J. 1993. Reengineering the

corporation: a manifesto for business revolution,

London, Nicholas Brearly.

Hannan, M. T. & Freeman, J. 1984. Structural inertia and

organizational change. American sociological review,

149-164.

Hiekkanen, K., Korhonen, J. J., Collin, J., Patricio, E.,

Helenius, M. & Mykkanen, J. 2013. Architects'

Perceptions on EA Use -- An Empirical Study. In:

Business Informatics (CBI), 2013 IEEE 15th

Conference on, Jul 15

th

-18

th

2013. 292-297.

Hollander, J. A. & Einwohner, R. L. 2004. Conceptualizing

Resistance. Sociological Forum, 19, 533-554.

Hsieh, H.-F. & Shannon, S. E. 2005. Three Approaches to

Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health

Research, 15, 1277-1288.

ISO/IEC/IEEE 2011. Systems and software engineering --

Architecture description. ISO/IEC/IEEE

42010:2011(E) (Revision of ISO/IEC 42010:2007 and

IEEE Std 1471-2000).

Kaisler, H., Armour, F. & Valivullah, M. 2005. Enterprise

Architecting: Critical Problems. In: HICSS-38.

Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences, 2005 Waikoloa,

Hawaii, USA.

Kezar, A. 2001. Understanding and facilitating

organizational change in the 21st century. ASHE-ERIC

Higher Education Report. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kitchenham, B. 2007. Guidelines for performing

Systematic Literature Reviews in Software

Engineering, Keele, Keele University.

Kotter, J. P. 2008. A sense of urgency, Harvard Business

Press.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

152

Kvale, S. 1996. Interviews: An introduction to qualitative

research interviewing, Thousand Oaks, California,

Sage Publications, Inc.

Lapalme, J. 2011. 3 Schools of Enterprise Architecture. IT

Professional, PP, 1-1.

Lapalme, J. 2012. Three Schools of Thought on Enterprise

Architecture. IT Professional, 14, 37-43.

Lee, A. S. 2010. Retrospect and prospect: information

systems research in the last and next 25 years. Journal

of Information Technology, 25, 336-348.

Lemmetti, J. & Pekkola, S. 2012. Understanding Enterprise

Architecture: Perceptions by the Finnish Public Sector.

In: SCHOLL, H., JANSSEN, M., WIMMER, M.,

MOE, C. & FLAK, L. (eds.) Electronic Government.

Berlin: Springer.

Mezzanotte, D. M., Dehlinger, J. & Chakraborty, S. 2010.

On Applying the Theory of Structuration in Enterprise

Architecture Design. In: Computer and Information

Science (ICIS), 2010 IEEE/ACIS 9th International

Conference on, 18-20 Aug. 2010 2010. 859-863.

Nassiff, E. 2012. Understanding the Value of Enterprise

Architecture for Organizations: A Grounded Theory

Approach. PhD Thesis, Nova Southeastern University.

Oreg, S., Vakola, M. & Armenakis, A. 2011. Change

Recipients’ Reactions to Organizational Change: A 60-

Year Review of Quantitative Studies. The Journal of

Applied Behavioral Science, 47, 461-524.

Oxford Dictionaries. 2010. Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010

[Online]. Oxford University Press. Available:

http://oxforddictionaries.com/ [Accessed Nov 18

th

2014].

Pardo del Val, M. & Martinez Fuentes, C. 2003. Resistance

to change: a literature review and empirical study.

Management Decision, 41, 148-155.

PEAF. 2010. 160 Character Challenge. What is the

Purpose of EA? [Online]. Pragmatic EA Ltd. Available:

http://www.pragmaticea.com/docs/160-char-

challenge-analysis.pdf [Accessed Sep 24

th

2014].

PEAF. 2013. Definition of "Enterprise" [Online]. Essex,

UK: Pragmatic EA Ltd. Available:

http://www.pragmaticef.com/frameworks.htm

[Accessed Feb 21

st

2013].

Pehkonen, J. 2013. Early Phase Challenges and Solutions

in Enterprise Architecture of Public Sector. Master's

Thesis, Tampere University of Technology.

Proper, H. A. 2013. Enterprise Architecture. Informed

steering of enterprises in motion. ICEIS 2013. Angers,

France.

Pulkkinen, M. 2008. Enterprise Architecture as a

Collaboration Tool. PhD Thesis, University of

Jyväskylä.

Ross, J. W., Weill, P. & Robertson, D. C. 2006. Enterprise

architecture as strategy: Creating a foundation for

business execution, Boston, Massachusetts, USA,

Harvard Business School Press.

Schekkerman, J. 2005. Trends in Enterprise Architecture

2005: How are Organizations Progressing? Amersfoort,

Netherlands: Institute for Enterprise Architecture

Developments.

Seppänen, V. 2014. From problems to critical success

factors of enterprise architecture adoption, Jyväskylä,

University of Jyväskylä.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. 1990. Basics of Qualitative

Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing

Grounded Theory, Sage Publ.

Syynimaa, N. 2010. Taxonomy of purpose of Enterprise

Architecture. 12th International Conference on

Informatics and Semiotics in Organisations, ICISO

2010. Reading, UK.

TOGAF 2009. TOGAF Version 9, Van Haren Publishing.

Van de Ven, A. H. & Poole, M. S. 1995. Explaining

Development and Change in Organizations. The

Academy of Management Review, 20, 510-540.

Zachman, J. A. 1997. Enterprise architecture: The issue of

the century. Database Programming and Design, 10,

44-53.

ModellingtheResistanceofEnterpriseArchitectureAdoption-LinkingStrategicLevelofEnterpriseArchitectureto

OrganisationalChangesandChangeResistance

153