Costing as a Service

Andr

´

e Machado

1

, Carlos Mendes

1

, Miguel Mira da Silva

2

and Jo

˜

ao Almeida

3

1

INOV, Lisbon, Portugal

2

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, T

´

ecnico Lisboa, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

3

Card4B, Systems S.A., Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords:

Costing, TDABC, Cost Templates, Cloud Computing, Cloud Services, SaaS.

Abstract:

Cost awareness and cost efficiency have always been major concerns to organizations from all industries but

in the last few years its importance grew due to the global economic and financial crisis. Considering their

small size and market exposure, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) need cost awareness and efficiency

more than ever. However, efficient and accurate costing methodologies are out of reach for most SMEs. In this

research we propose that costing should be offered as a service to reduce the cost of cost analysis. Our research

proposal is a cloud-based costing system that offers costing as a service using Time-Driven Activity Based

Costing (TDABC) methodology and the concept of Business Process Costing Templates. When combined,

they reduce the cost of cost analysis, especially for SMEs. We used the Design Science Research Methodology

(DSRM) to conduct our research. This proposal was demonstrated in three Portuguese organizations and

evaluated with feedback gathered from interviews and results from the system instantiation in all organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprises are becoming increasingly complex and

managing that complexity is a growing challenge.

Competition is fierce among these entities that always

tried to differentiate between themselves through a

variety of factors, one of which is efficiency. Cost ef-

ficiency has always been a major concern to organiza-

tions but in the last few years its importance grew due

to global economic and financial crisis. Due to their

small size and market exposure, Small and Medium

Enterprises (SMEs) need cost efficiency more than

ever (OCDE, 2009).

However, as organizational complexity grows, so

does the complexity of cost analysis (Wileman, 2010).

Information about how and where the money was

spent is a concern of organizations across all indus-

tries. Knowledge about costs distribution and true un-

derstanding of overhead costs allocation is essential

for an enterprise to focus on the most profitable prod-

ucts and services (Delloite, 2011).

In order to obtain detailed information about costs

and overheads distribution several cost methodolo-

gies were developed. These methodologies evolved

and differentiated themselves from traditional cost ac-

counting systems to better distribute overhead costs

that have been rising inside organizations in recent

years (Miller and Vollmann, 1985). The increasing

importance of overhead costs comes from the fact

that the industry has evolved from manufacturing to

services (

ˇ

Skoda, 2009). This development implied a

substantial growth of overhead costs (Miller and Voll-

mann, 1985;

ˇ

Skoda, 2009).

Organizations using these accurate costing

methodologies know exactly where resources are

being spent and what is the profitability of their

products or services. However, the adoption of these

costing methodologies is far behind of what would

be expected. The lack of adoption is explained by

the high costs of these methodologies for SMEs

since they require time, expertise and expensive and

complex software solutions that are out of reach for

the most of these organizations (Hall et al., 2011).

2 PROBLEM

Costing has been a major concern to all organizations

since their genesis. As a competitive advantage, cost

efficiency has been something that all organizations

tried to achieve in order to increase their profit mar-

gins or reduce the price of their products or services.

Cost efficiency is recognized as one of the most im-

portant aspects in respect to the competitive advan-

173

Machado A., Mendes C., Mira da Silva M. and Almeida J..

Costing as a Service.

DOI: 10.5220/0005373401730181

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2015), pages 173-181

ISBN: 978-989-758-098-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

tages of an organization.

Normally, organizations resort to cost accounting

in order to analyse costs and achieve the desired cost

reductions. This approach has a major issue: tradi-

tional cost accounting systems give low detailed in-

formation and lack the needed granularity to prop-

erly do cost analysis and, therefore, cost reduction.

Not least, most accounting systems are focused on

mandatory state-demanded reports (Hicks and Cost-

ing, 2002) showing only large blocks of information

totally misaligned with the organization’s business

processes. Therefore, when it comes to calculate the

cost of a product or service, traditional methodolo-

gies give inaccurate values, mostly because they lack

the needed granularity and differentiation of informa-

tion (Lambert III and Chen, 1996). Often, such infor-

mation is inaccurate because of wrong distribution of

overhead costs. Correct distribution of overhead costs

is truly essential since they have grown from being a

minor share of the total costs to the major one (

ˇ

Skoda,

2009).

Presently, there are several costing methodolo-

gies to address the abovementioned problem. These

methodologies resort to the activities that occur in-

side the organization to design the flow of costs from

the inputs (e.g. material) to the outputs of an organi-

zation (products or services). This cost awareness al-

lows organizations to take measures to improve their

efficiency.

The problem with these accurate costing method-

ologies is that they require a lot of expertise and are

normally supported by very expensive and complex

software solutions (Hall et al., 2011). Whereas large

organizations can support the costs associated with

the required expertise and software solutions, SMEs

cannot (Hall et al., 2011). It is crucial that SMEs have

access to these accurate cost methodologies since they

operate in a market that is more competitive (Nandan,

2010) and they are more exposed to the effects of an

economic crisis (OCDE, 2009).

To solve this problem we propose that costing and

cost analysis should be offered as a service instead of

as an investment in a one-time project. This approach

should enable organizations to access accurate cost-

ing methodologies because costs are diluted over time

and the tools needed to perform this cost analysis are

also offered as a service. Our proposal will also give

organizations the ability to do on-demand cost anal-

ysis so that they can constantly evaluate the flow of

costs as well as take measures to improve their cost

efficiency.

3 RELATED WORK

We will provide an overview of the tools and methods

available that could contribute to solve the identified

problem.

Cost Accounting (or costing) can be defined as

the process of collecting, classifying, assigning and

analysing the costs associated with the activity of an

organization (Blocher, 2005). Cost Accounting pro-

vides the detailed cost information that management

needs to control current operations and plan for the fu-

ture. The goal of cost accounting is to gather all pos-

sible information so that it can be structured and used

by management to take decisions and measure the or-

ganization’s performance (Vanderbeck, 2012; Cooper

and Kaplan, 1987).

3.1 Costing Methodologies

3.1.1 Activity based Costing

ABC methodology defines an activity as an action ex-

ecuted inside an organization (e.g. packaging) that

has a particular cost rate based on the cost of the re-

sources allocated to that activity. Allocation of re-

sources to activities and then to products or services

is done based on interviews to those involved in the

activities as well as in some estimates provided by the

management team. This process results on splitting

the costs related to the resources used by the activities

using variables like percentage or headcount. Output

costs are calculated adding the costs of all the activ-

ities that were needed to create the final product or

service (Blocher, 2005).

Traditional costing methodologies assign over-

head costs by volume, that is, overhead costs are dis-

tributed by products using some variable (or driver)

that reflects capacity usage (e.g. number of hours)

regardless of the specificities of the product. On the

other hand, ABC uses activities which mean that dif-

ferent products may use a set of different activities

and therefore a set of different cost rates to calculate

the final cost of a product or service.

Although ABC has some advantages over tradi-

tional costing systems it also has some pitfalls. First,

costs are calculated using individual and subjective

estimates. The accuracy of these estimates may be

questionable since, in most cases, there is no evidence

of correctness. Wrong estimates may distort measure-

ments (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007). Second, ABC

requires not only the creation of an activity for ev-

ery task performed inside the organization but also its

cost specification. Thus, the complexity of the model

grows with the number of activities. Finally, since it

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

174

is common to have activities with variable costs (e.g.

special packing vs standard packing) and ABC de-

fines activities as single tasks with fixed cost rates,

models tend to have many similar activities just to

simulate variable costs.

3.1.2 Time-Driven Activity Based Costing

Time-Driven Activity Based Costing (TDABC) (Ka-

plan and Anderson, 2007; Kaplan and Anderson,

2004) is an alternative costing methodology to ABC

focused on assigning overhead costs to cost outputs.

The TDABC model simulates the actual processes

used to perform work throughout an enterprise, there-

fore capturing far more variation and complexity than

a conventional ABC model. Such variation and com-

plexity is captured without significant demand for

data estimates or processing capabilities. TDABC as-

signs resource costs directly to the cost objects requir-

ing only two sets of estimates: the cost of supplying

resource capacity and the capacity used by each trans-

action processed (Kaplan and Anderson, 2007).

Regarding flexibility and concerning the limita-

tions of ABC of each activity reflecting only one

factor/condition, TDABC introduces the concept of

time-equations to model the different resources con-

sumed by an activity (Dejnega, 2011). If we take as an

example the packaging of an order that takes longer

when gift wrapping is requested, in ABC there would

be two activities: one for standard packaging and an-

other for gift wrapping. However, in TDABC it is pos-

sible to express this variation with a time-equation.

Finally, TDABC provides mechanisms to gather

information about its own accuracy and to identify

possible wastes or inefficiencies (Kaplan and Ander-

son, 2007).

3.2 Business Process Cost Templates

Business Process Cost Templates is a method to re-

duce the costs of adopting efficient costing method-

ologies, such as TDABC, through re-utilization and

standardization of business processes for organiza-

tions inside the same field or industry. The main goal

of these templates is to dilute the costs associated with

the analysis required to implement a costing method-

ology, in particular TDABC, making the adoption of

such methodologies more affordable (Lourenc¸o and

Mira da Silva, 2013).

The method that creates a template for a particu-

lar field is composed of two distinct phases: a Mod-

elling Phase and an Application Phase. The first is

done only once and is where the field or industry is

analysed and a generic cost model is developed. The

second results of the application of the template pro-

duced. The template is instantiated and the specifici-

ties of the organization are set. These specificities

may include addition or removal of activities, chang-

ing the coefficients in time-equations, or adding some

unrepresented condition. This adjustment is crucial

since not all organizations are identical, even though

they belong to the same industry or field (Lourenc¸o

and Mira da Silva, 2013).

4 PROPOSAL

We briefly describe our proposal as a cloud-based

costing service that uses TDABC and the concept

of Business Process Cost Templates to reduce the

costs associated with cost analysis.

4.1 Costing Service Objectives

We highlight from our cloud-based costing ser-

vice the following features: Time-Driven Activity

Based Costing methodology, Business Process Cost-

ing Templates, Creation/Edition of Business Pro-

cesses and Time-Equations, What-if Analysis, Data

Integration, Data Visualization and Automatic Pre-

configuration.

Offering a costing service in a cloud environment

helped us achieve the needed technological cost re-

duction. Current solutions require local software in-

stallations that raise the costs of the service because,

in addition to compelling the purchase of the techno-

logical equipment needed, it also implies operational

costs. Those tools are also very complex and require

expertise whenever modifications to the model are

needed. These issues prevented managers from per-

forming cost analysis as an ongoing process.

As for the costing methodology, we adopted TD-

ABC for the reasons stated in the Related Work (sec-

tion 3). TDABC is an accurate costing methodol-

ogy that solves the problems identified in previous

methodologies and that is simple to understand and

implement, providing quick benefits for those who

adopt it (Pernot et al., 2007). TDABC also has clear

connections with BPM that helped us connect it with

Business Process Costing Templates.

Regarding Business Process Costing Templates,

we chose to use them within our service because they

provide a way of creating cost templates to a given

industry and distribute them for all the organizations

that operate within that industry. These templates can

be created and modified by an organization or by a

cost analysis expert and included within our tool. Pro-

viding cost templates to more than one company leads

CostingasaService

175

to cost reduction, since the cost of creating a template

can be distributed by multiple organizations. These

templates can be later improved or adapted to the re-

ality of the organization deploying the template. Even

though the organization may incur in a cost by doing

this, it will be a lower cost when compared to the cost

of a complete analysis.

Finally, What-if Analysis, Data Integration and

Data Visualization, are meant to provide means of

assessing the organization’s performance. Although

these features are not directly related to the cost re-

duction of the cost analysis they are required to com-

ply with the guidelines proposed by TDABC.

4.2 Costing Service - Analysis Process

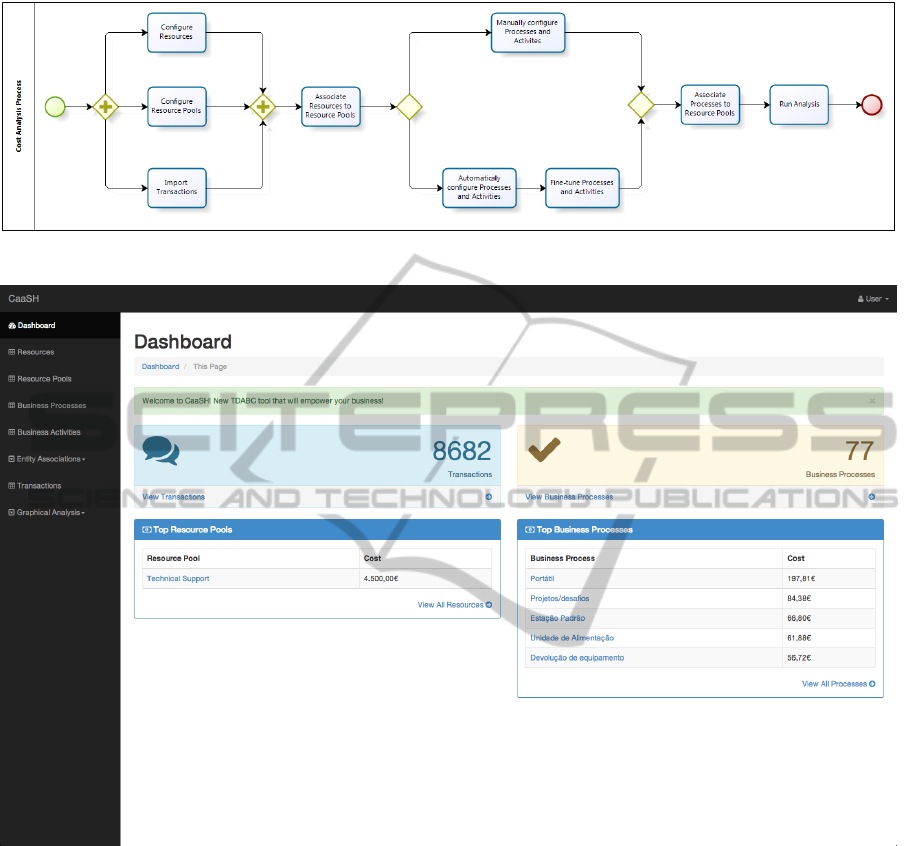

Figure 1 shows the process of performing a cost anal-

ysis using the costing service. Users should start by

configuring resources and resource pools and import-

ing transactions. If the costing service is being used

by more than one user, each one may be account-

able for one of the activities. In the case of the re-

sources, users should define, for every resource be-

longing to the organization, the name of the resource,

its monthly capacity and the cost of providing such

capacity. On the other hand, regarding resource pools,

users should define the name of the resource pool

and its classification, whether it is a support resource

pool or a functional resource pool. Afterwards, users

should configure the resource pool structure, that is,

which support resource pools belong to which func-

tional resource pools.

Users must also associate resources to resource

pools. Resources can either be associated to support

or functional resource pools. After completing these

associations, resource pools will have their cost calcu-

lated so that users can know the costs of their resource

structure before completing the analysis.

Afterwards, users should decide if they want to

automatically configure business processes and activ-

ities or if they want to manually specify them. The

main difference is closely related to the quality of the

data available. If users know that their data matches

the processes of the organization, they can let the tool

automatically configure them. On the other hand, if

users already have some sort of ”optimized” business

process template, they should manually configure the

tool. Users may also let the costing tool infer busi-

ness processes and then fine-tune them. We encour-

age users to perform an automatic configuration since

this simplifies the process of analysis even further.

Finally, users should associate the functional re-

source pools to the business processes that those func-

tional resource pools are accountable for and then

compute the analysis. Running the analysis finishes

the process of cost analysis. However, users may

change resource cost values, fine-tune activities and

business processes or change associations and then re-

compute analysis.

4.3 Costing Service Tool

We developed our costing tool according to the guide-

lines defined by both TDABC and Business Process

Costing Templates meaning that they represented our

requirements document.

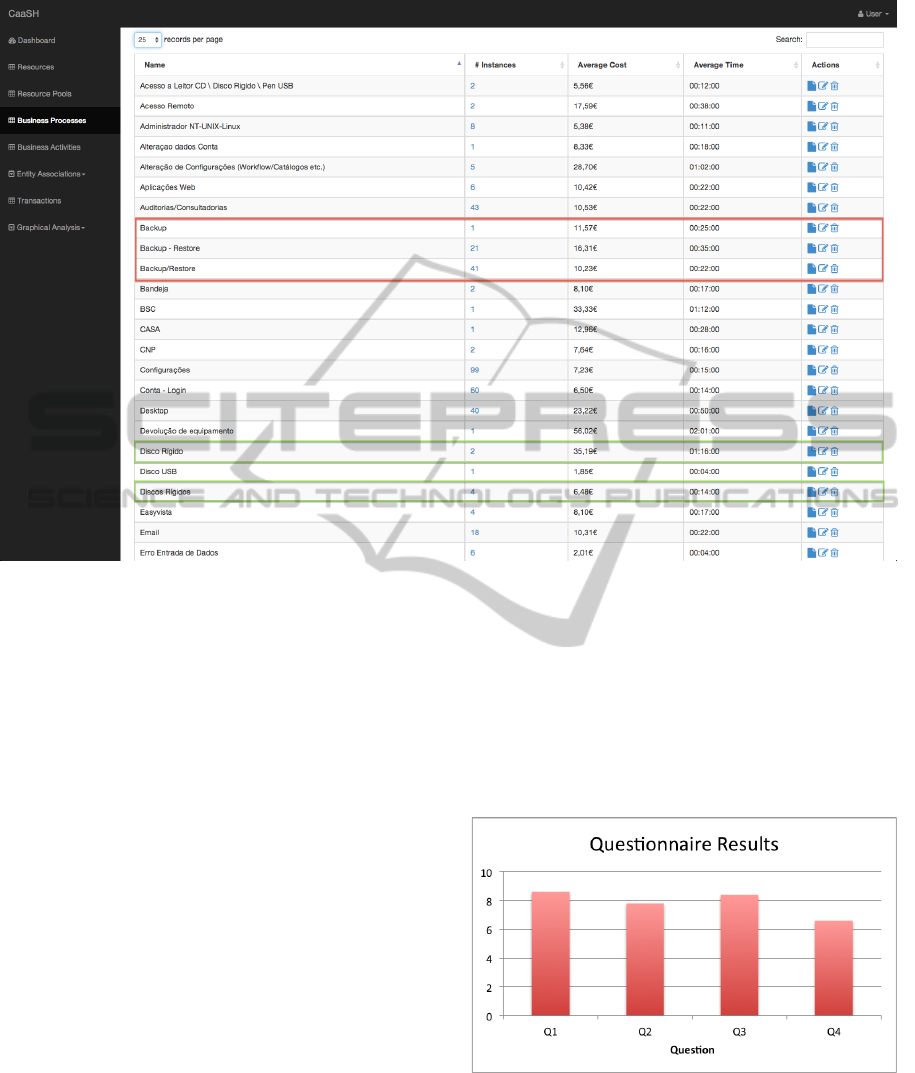

Figure 2 shows the Dashboard of our tool. We

provide information regarding the number of Trans-

actions (8682) used to make the analysis, the number

of Business Processes (77) identified and the list of

the top five most costly Resource Pools and Business

Processes.

5 DEMONSTRATION

We demonstrated our proposal by instantiating our

artefact (the costing service) in three real world Por-

tuguese organizations, namely ”Social Security IT In-

stitute”, ”Defence Data Center” and “Card4B”.

The demonstrations consisted in instantiating the

costing service, i.e., creating the cost template, within

the costing tool, to the organization being tested. This

includes the definition of resources, resource pools,

business activities, business processes and the rela-

tionships between these entities to the particular en-

vironment of the organization being tested.

5.1 Social Security IT Institute

The Social Security IT Institute is a public institute,

integrated in the indirect state administration, with ad-

ministrative and financial autonomy. It is an organi-

zation with nationwide intervention. Although sev-

eral state competences have been assigned to the In-

stitute, we focused our demonstration in the service

desk competences.

Following the process described in section 4.2, we

started by gathering relevant data to feed the transac-

tional data needed to perform the analysis. We asked

the Institute to provide us with a CSV file containing

the data to be imported as transactions. We had access

to 8682 real transactions to perform the analysis.

Regarding the resources, there are several re-

sources involved in all the business processes and de-

partments inside the organization. These resources

are diversified and include technical and management

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

176

Figure 1: Costing Service - Analysis Process.

Figure 2: CaaSH - Dashboard - Costing Tool.

staff, electricity, rents, material and equipments. Al-

though all these resources and resource pools (such as

the Technical Support department) are properly iden-

tified, the organization opted to avoid gathering the

unit costs of each resource and their contribution to

the resource pools. This decision was justified since

the organization had been previously involved in a

cost analysis project. From the results of this former

project, the Institute knew the daily cost of the tech-

nical support staff. However, they were unable to link

it to the execution of the business processes, which is

the main objective of our demonstration.

Based on these limitations, we defined a resource

and a resource pool that matched the daily value sup-

plied. We knew that the monthly time capacity of this

resource was 8 hours/day and 22 days/month, which

was converted in minutes with a 10% waste on work-

ing hours, giving the final monthly time capacity of

9504 minutes for each technical support worker. If

we assume (since we cannot disclose the real value)

the cost of providing such capacity as 200e/day, the

cost of providing 9504 minutes of technical support

labour would cost 4400e. Since there is no other sup-

port resources or resource pools, this means that the

capacity cost rate (CCR) of this resource is 0,46e.

From the 8682 transactions supplied, the auto-

matic configuration of the costing tool was able to de-

tect 77 business processes with 791 unique business

processes instances. This means that the analysis was

performed using data from 791 complete executions

CostingasaService

177

of a business process (from the 77 identified). Fig-

ure 3 shows a sample of the results obtained from the

analysis. The sample shows, for each business pro-

cess identified, the average time and cost of execution

as well as the number of instances that were identified

for that business process. The red and green rectan-

gles also show another interesting result from the cost

analysis. The red rectangle shows a group of three

business processes that were identified by the costing

tool and that correspond to the same business process,

as we were able to verify with the Social Security IT

Institute management. This results from the wrong

definition of workflows inside the IT Service Man-

agement software (EasyVista) which leads to wrong

categorization of incidents/service requests in the ser-

vice desk. The green rectangle shows the same prob-

lem described earlier but this time with an even minor

difference (name pluralization).

Not only the costing tool delivered what was ex-

pected, i.e., the cost of executing the business process

that accomplishes the resolution of a service request

or incident, but it also provided valuable insights to

the organization regarding the workflows definition in

the IT Service Management software. The organiza-

tion can easily know the average time and cost of exe-

cuting a business process. Moreover, the institute can

further analyse the data and find the cost for every

execution of every business process. The Social Se-

curity IT Institute management members considered

these results very useful since they can now further

analyse the different costs that the same business pro-

cess generates. For instance, a desktop related inci-

dent has an average cost of 23,22e but the minimum

cost and the maximum cost of such incident was, re-

spectively, 2,31e and 70,83e. Having this informa-

tion, the management may now try to understand what

motivated such difference and take measures to miti-

gate the cause.

5.2 Defence Data Center

The Defence Data Center belongs to the General Sec-

retariat of the Ministry of National Defence (Portu-

gal) and among its several competences they are also

responsible for service desk activities.

The Defence Data Center service desk uses

EasyVista software for IT Service Management, i.e.,

the same software used by the Social Security IT In-

stitute. It is also configured according to the best

practices defined internally (ITIL). This means that

the demonstration was almost identical to the previ-

ous case. Again, we followed the costing service pro-

cess of analysis (section 4.2).

Results obtained from the analysis are similiar to

those shown in Figure 3. Again, we detected groups

of business processes that were identified by the cost-

ing tool and that correspond to the same business pro-

cess. As we stated before, this results from the wrong

definition of workflows inside the IT Service Manage-

ment software.

5.3 Card4B

Card4B develops and operates integrated mobility

solutions through interoperable contactless ticketing,

passenger information, embedded systems and smart-

phones, systems integration and business intelligence.

Presently, Card4B is developing a project, designated

ecoDrive - Intelligent Eco Driving and Fleet Man-

agement, which is a multidisciplinary project, target-

ing the public transportation network, in which INOV

is responsible for the identification of business pro-

cesses (BPMN) and the cost analysis of those busi-

ness processes using a TDABC approach.

The costing service described in the proposal (sec-

tion 4) was adopted as a solution for the ecoDrive

project since it delivered all the needed features to

accomplish the objectives defined. However, this

project required that the identification of business pro-

cesses and activities was done prior to the system de-

ployment, meaning that we would only have access to

real transactional data after the system enters in pro-

duction, since there is no digital data from the past.

Starting with the business processes, we were able

to identify 10 different business processes, each one

with its distinct set of activities. For example, we

identified a business process ”Occurrences” that is re-

lated to the different events that may cause changes to

the operational service of a bus. The activity list of

this business process includes ”Change Driver” and

”Change Vehicle”. Another example was the busi-

ness process ”Corrective Maintenance” that features

activities such as ”Repair of damage” and ”Damage

Report”. These 10 business processes and respective

activities are the ones that will constitute the founda-

tion for the transactional data to be exported from the

software being developed by Card4B for the public

transportation industry.

As we stated before, we didn’t have access to real

transactional data since the system is not in produc-

tion yet. In this particular case, our tool will im-

port transactional data from JSON web services rather

than from a CSV file, enabling the costing tool to get

data in real time. As a result, after configured, the

costing tool can pull data, in a given time interval, so

that it can produce updated metrics without user in-

tervention.

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

178

Figure 3: CaaSH - SS IT Institute - Business Processes Sample.

6 EVALUATION

The goal of this evaluation is to determine if the so-

lution proposed in the Proposal (section 4) solves the

problem stated in the Problem (section 2).

The evaluation method will consist in the follow-

ing steps:

1. Interviews and Questionnaires. Gather feed-

back from the proposal through the demonstration

and identify improvements;

2.

¨

Osterle et al. Principles. To formally evaluate

the research;

3. Demonstration’s Critical Review. To critically

evaluate the research, objectives fulfillment and

the demonstrations conducted;

6.1 Interviews and Questionnaires

After demonstrating our costing service, we con-

ducted a small questionnaire to those involved so that

we could obtain a more structured feedback. The

questionnaire was made to five interviewees with the

following business roles: Planning, Quality and Au-

dit Manager, Budget Manager, Planning and Control

Manager, Accountant for Client Support and an IT

Director.

We carried out four questions to these profession-

als that helped us assess the artefact utility and the ful-

fillment of the objectives defined earlier. These ques-

tions were also defined having in mind the needed in-

formation to formally evaluate the research.

Figure 4: Questionnaire Results.

Figure 4 shows the questionnaire results which av-

eraged 7,85 out of 10. We also gathered feedback

from the interviews that provided us insights in dif-

ferent topics needed to evaluate this research as we

will further detail in this section.

CostingasaService

179

6.2

¨

Osterle et al. Principles

¨

Osterle et al. proposes an evaluation method based

within four principles (

¨

Osterle et al., 2010). Our re-

search met the four principles of

¨

Osterle. This evalua-

tion is based on the feedback received from practition-

ers, which were described in the previous sections.

1. Abstraction. The artefact we propose can be ap-

plied to the majority of the service-oriented or

process-based organizations;

2. Originality. None of the interviewees had knowl-

edge of any research or product similar to the pro-

posed artefact. Similar research was not found re-

garding the costing service;

3. Justification. Our artefact is justified by the lack

of a similar solution and from the positive feed-

back gathered during this research;

4. Benefit. According to the interviewees, at least in

the industries consulted, there would be a valuable

benefit, since it would provide an easier and more

affordable way to perform a cost analysis.

6.3 Demonstration’s Critical Review

We consider that our research was properly evaluated

and tested with our demonstrations. We demonstrated

our proposal in three Portuguese organizations, from

two distinct industries, with the objective of providing

those organizations with new ways to conduct simple

and reliable cost analysis.

Our demonstrations targeted three organizations

that are making clear efforts to consider business pro-

cess costing a priority. Two of the three organiza-

tions (the service desks), already have their services

oriented according to best practices such as ITIL and

ISO 20000. That gave us an advantage regarding the

costing service implementation. Although our service

provides an easy way to start costing business pro-

cesses and services, we do realize that the organiza-

tions deploying such service should have a consider-

able maturity in their architecture.

We were able to deliver average cost per business

process and real cost per business process instance.

We consider the latter to be a great benefit to service-

oriented organizations since it enables organizations

to comprehend the average cost of supplying a service

or executing a business process but also the real cost

for every business process instance executed. This

helps organizations detect erroneous paths and singu-

lar problems that occurred at a moment in the organi-

zation.

Finally, every interviewee that saw the costing ser-

vice configuration and use considered the process of

conducting a cost analysis using our tool very easy

and understandable.

7 CONCLUSION

Cost efficiency has always been a major concern to

organizations from all industries around the world. In

recent years, economic crisis and increased competi-

tion in an increasingly global economy pushed even

further the need for cost efficiency and cost aware-

ness. It became crucial to assess and benchmark an

organization’s performance and to identify improve-

ment opportunities across all sectors of the organiza-

tion and over the cost stream.

Our artefact is a cloud-based costing service

meant to provide costing as a service. Our main ob-

jective was to develop a solution to reduce the costs

associated with cost analysis so that SMEs can reach

the accurate costing methodologies needed to assess

an organization’s cost efficiency and performance.

We validated our proposal in three Portuguese or-

ganizations belonging to two different industries: Ser-

vices industry (two Service Desks) and the Public

Transportation industry. We completed the demon-

strations by instantiating the proposed costing service.

7.1 Main Contributions

We believe that our proposal brings a valuable con-

tribution in the context of costing and cost analysis.

The resulting costing service allows organizations to

conduct a bigger share of the cost analysis without

demanding significant levels of expertise or capital.

The proposed costing service not only provided a

solution to the problem of high costs of cost analysis

but also delivered a costing tool capable of correctly

and completely support TDABC and Business Pro-

cess Costs Templates. These methods combined with

the capabilities of our costing tool produced well-

defined steps that act as a guideline for both analysts

and managers looking for a cost analysis solution.

The end result is a costing service capable of deliver-

ing the ability for an organization to do cost analysis

with internal resources and expertise, without needing

substantial investment.

7.2 Limitations

The limitations regarding our proposal can be divided

into two groups, technical limitations and conceptual

limitations.

Regarding the technical limitations, although we

consider our costing tool to be more than just a pro-

ICEIS2015-17thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

180

totype, we must state that it lacks some characteris-

tics needed to be a full cloud-based costing service.

The developed costing tool does not support integra-

tion and importing of tax and analytical accounting

data. In order to avoid data input mistakes and to

enable high volumes of data integration this would

be mandatory. We also consider that the developed

costing tool, although producing some useful metrics,

lacks the ability to produce management reports.

As for the conceptual limitations, they are related

to profitability, capital and investment characteristics

that are needed to correctly reflect all the costs within

the analysis. The research process and the interviews

revealed that although costs and cost analysis are ma-

jor concerns to organizations, they are strongly tied to

capital costs, working capitals, return on investments

and profitability. Although we excluded from the be-

ginning of this research such concepts and metrics,

we must acknowledge that the lack of such character-

istics is a limitation that must be addressed in future

research.

7.3 Future Work

Although we achieved three full demonstrations in

two distinct industries, we consider that applying

the service to more complex and different industries

would be desirable since that could further validate

the proposed costing service. Our demonstrations

were carried using a significant volume of transac-

tional data. However, high transactional volume in-

dustries would be advisable to further test the costing

service.

Another interesting aspect would be to develop

BPMN importing capabilities within our costing tool.

Since some organizations already have their business

processes modelled in BPMN it would simplify the

process of cost analysis even further.

Finally, the costing tool should also be able to im-

port business processes and activities specific drivers.

This would enable the tool to produce different met-

rics other than just the cost of business processes and

activities. Since our effort was to develop a service

to reduce the cost of cost analysis, we opted to leave

this feature as a future development because it would

require transactional data to be much more specific

than the datasets we had access to, conditioning the

costing service validation and demonstration.

REFERENCES

Blocher, E. (2005). Cost Management: A Strategic Empha-

sis. McGraw-Hill College.

Cooper, R. and Kaplan, R. S. (1987). How Cost Account-

ing Systematically Distorts Product Costs. Account-

ing and Management: Field Study Perspectives, pages

204–228.

Dejnega, O. (2011). Method: Time Driven Activity Based

Costing - Literature Review. Journal of Applied Eco-

nomic Sciences, 5(1(15)/ Spring 2011):7–15.

Delloite (2011). CIO Survey Report 2011 The Guerilla CIO

Working Smarter to Add Value. Technical report.

Hall, O. P., McPeak, C., et al. (2011). Are SMEs ready for

ABC? Journal of Accounting and Finance, 11(4):11–

22.

Hicks, D. T. and Costing, A.-B. (2002). Making It Work for

Small and Mid-Sized Companies.

Kaplan, R. S. and Anderson, S. R. (2004). Time-Driven

Activity-Based Costing. Harvard Business Review.

Kaplan, R. S. and Anderson, S. R. (2007). Time-Driven

Activity-Based Costing: A simpler and more powerful

path to higher profits. Harvard Business Press.

ˇ

Skoda, M. (2009). The Importance of ABC Models in Cost

Management. Annals of the University of Petrosani,

Economics, 9(2):263–274.

Lambert III, S. and Chen, K. H. (1996). Overhead Cost

Pools. Internal Auditor, 53(5):62.

Lourenc¸o, A. G. and Mira da Silva, M. (2013). A cloud-

based service for affordable cost analysis. 19th Amer-

icas Conference on Information Systems.

Miller, J. G. and Vollmann, T. E. (1985). The Hidden Fac-

tory. Harvard Business Review, 63(5):142–150.

Nandan, R. (2010). Management Accounting needs of

SMEs and the Role of Professional Accountants: A

Renewed Research Agenda. Journal of Applied Man-

agement Accounting Research, 8(1):65–78.

OCDE (2009). The Impact of the Global Crisis on SME and

Entrepreneurship Financing and Policy Responses.

Technical report.

¨

Osterle, H., Becker, J., Frank, U., Hess, T., Karagiannis, D.,

Krcmar, H., Loos, P., Mertens, P., Oberweis, A., and

Sinz, E. J. (2010). Memorandum on Design-Oriented

Information Systems Research. European Journal of

Information Systems, 20(1):7–10.

Pernot, E., Roodhooft, F., and Van den Abbeele, A. (2007).

Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing for Inter-library

Services: A Case Study in a University. The Journal

of Academic Librarianship, 33(5):551–560.

Vanderbeck, E. J. (2012). Principles of Cost Accounting.

Cengage Learning.

Wileman, A. (2010). Driving Down Cost: How to Manage

and Cut Costs-Intelligently. Nicholas Brealey Pub.

CostingasaService

181