Brain Race

An Educational Mobile Game for an Adult English Literacy Program

Nada Soudy

1

, Silvia Pessoa

2

, M. Bernardine Dias

3

, Swapnil Joshi

1

,

Haya Thowfeek

1

and Ermine Teves

4

1

Computer Science Department, Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, Doha, Qatar

2

English Department, Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar, Doha, Qatar

3

The Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

4

Computer Science Department, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Keywords: Mobile, Game-based Learning, Motivation, Implementation.

Abstract: This paper investigates the role and impact of Brain Race (BR), a customized mobile game-based learning

tool, on the learning and teaching experiences of teachers and learners in a community adult English literacy

program in Qatar. Relying on observations, formal interviews, and surveys with teachers and learners, this

paper examines the implementation process of introducing BR in a classroom, the interaction of teachers and

learners with BR and their opinions on BR, and BR’s perceived impact on learner motivation, engagement,

and learning outcomes. Results indicate that although BR motivates learners and allows them to practice

English concepts, certain issues, such as equipment used, scheduling, and content relevance, must be

addressed in order to make the experience more efficient and valuable to both teachers and learners. The paper

argues that learners and teachers have a variety of preferences, and thus it is important that they are able to

decide for themselves how they want to include game-based learning tools, such as BR, into their classrooms.

We conclude with recommendations to improve the implementation process so that learners can benefit more

from BR and similar games.

1 INTRODUCTION

There is no doubt that technology has become an

integral part of our daily lives. Students all around the

world are constantly surrounded with information and

communication technology (ICT) tools (Huizenga,

Admiraal, Akkerman, and Dam, 2009). As will be

shown in this paper, there has been a surge in research

on the impact that different technology tools, both

hardware and software, can have in an educational

environment. More specifically, there has been an

increasing interest in investigating the use of games

in the classroom. This paper is primarily interested in

investigating the impact of Brain Race, a customized

mobile game-based tool, on the learning and teaching

experiences of teachers and learners in a community

adult English literacy program in Qatar. After

providing an overview of the literature and

background information on the project and the target

population, we discuss our methodology and our

findings. We conclude with recommendations to

facilitate the process of introducing games into the

classroom.

2 RELATED WORK

Dempsey, Lucassen, Haynes, and Casey (1996)

define games as “a set of activities involving one or

more players. It has goals, constraints, payoffs, and

consequences. A game is rule-guided and artificial in

some respects. Finally, a game involves some aspect

of competition, even if that competition is with

oneself” (p.2). The literature reviewed here discusses

the potential usefulness of a variety of games:

computer games, online games, videogames, console

games, and mobile games. The purpose of this review

is to understand the benefits and challenges that come

up when games are introduced into a classroom

environment, and the recommendations for future

work.

Several articles provide reviews of previous work

done to explore the potential of technology and games

in a learning environment (Huizenga et al., 2009;

McClarty et al., 2012; Osman and Bakar, 2012;

Papastergiou, 2009; Randel, Morris, Wetzal, and

Whitehill, 1992; Rosas et al., 2003). The literature

highlights the impact of computer, mobile, or

34

Soudy N., Pessoa S., Dias M., Joshi S., Thowfeek H. and Teves E..

Brain Race - An Educational Mobile Game for an Adult English Literacy Program.

DOI: 10.5220/0005410400340045

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 34-45

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

videogames on motivation, but not so much on

academic development or learning achievement

(Papastergiou, 2009).

Educators are interested in the relationship

between games and education, because they see that

games can be very beneficial. The most common

benefits of introducing digital games in the classroom

are that they enhance student motivation,

engagement, and cognitive skills (Huizenga et al.,

2009; Ke and Grabowski, 2007; McClarty et al.,

2012; Mifsud, Vella, and Camilleri, 2013; Rosas et

al., 2003; Tüzün, Yilmaz-Soylu, Karakuş, İnal, and

Kizilkaya, 2009; Virvou, Katsionis, and Manos,

2005; Williamson and Futurelab, 2009). In their

investigation of the impact of videogames on

economically disadvantaged students in Chile, Rosas

et al. (2003) found that because students reacted

positively to the games, teachers started introducing

the games more often in class (p.90).

In their review of the literature, McClarty et al.

(2012) also found that games are tools students can

use to constantly practice their school material. They

found that games provide “immediate feedback” (p.

8-9) to students, and “can be a tool for personalized

training” (p. 10). Teachers also noted that computer

games help improve students’ ICT skills, “higher-

order thinking skills (such as logical thinking,

planning and strategizing)” (p.2), and encourage

more interactions amongst the students, and between

teachers and their students (p. 2-3).

Other benefits include encouraging student

independence (Tüzün et al., 2009), and the ability to

play anywhere (for mobile games at least), (Kam et

al., 2008). Kam et al. (2008) and Rosas et al. (2003)

found that mobile phones and videogames

(respectively) are cheaper than other technological

tools, and hence, can benefit less-economically

privileged students. Research has also shown that

students believe games, such as videogames, can help

enhance their learning experiences (Mifsud et al.,

2013). Rosas et al. (2003) noted that videogames

assist teachers as well, as they offer a different

teaching method, provide prompt feedback on student

performances, and make class material more

interesting for students (p.74).

However, despite these benefits, there are

important factors that hinder or complicate the

implementation of games in a classroom

environment. A common factor is how teachers

perceive the role of such games on the educational

development of their students (Groff, Howells,

Cranmer, and Futurelab, 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013;

Rosas et al., 2003; Rice, 2007; Williamson and

Futurelab, 2009). Some researchers found that

teachers believe introducing games into the

classroom will encourage them to be less social

(Mifsud et al., 2013). To address this, researchers

highlight the importance of familiarizing teachers

with the potential of such games on education, and/or

training them on how to best utilize these tools in their

classrooms, and/or ensuring that schools provide

teachers the necessary technical, financial,

infrastructure, and administrative support. (Groff et

al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013; Rosas et al., 2003,

Tüzün, 2007).

Another common factor is the extent to which

these games relate to the curriculum taught in the

classroom, specifically the content used in the games

(Groff et al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013; Rice, 2007).

Researchers found that teachers and/or school

administrators resist the use of games because they do

not find that the content and/or the games are context

specific or customized enough for their students to

benefit from them (Osman and Bakar, 2012). On a

related note, teachers’ decision to introduce games

into the classroom is influenced by the extent to

which games measure and adapt to students’

individual performances, (Mifsud et al., 2013),

something that has already been proven to be highly

beneficial to students (Hwang, Sung, Hung, Huang,

and Tsai, 2012; Tseng, Chu, Hwang, and Tsai, 2008;

Wang and Liao, 2011).

However, even if teachers/school administrators

see the value of using games in the classrooms, other

factors come up that hinder them from doing so. One

common factor found in the literature is the difficulty

of fitting games into rigid class schedules (Groff et

al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013; Rice, 2007).

Unsurprisingly, many technical issues come up

when it comes to implementing these games in a

classroom. In addition to lack of suitable

infrastructure mentioned earlier, and technical

difficulties (Mifsud et al., 2013; Shiratuddin and

Zaibon, 2010), some schools face licensing issues that

prevent games from being played on multiple

technology tools (Williamson and Futurelab, 2009).

And finally, some factors that hinder the use of

games in the classroom come from the students

themselves. Bourgonjon, Valcke, Soetaert, and

Schellens (2010) argue that one must not

automatically assume that all students in today’s

world enjoy video games. For example, some

students find it difficult to understand how games can

help with their education (Bourgonjon et al., 2010;

Williamson and Futurelab, 2009). Other students

might not be interested in the games because they are

not appealing enough (Rice, 2007). Others find the

instructions difficult or the games difficult to play

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

35

(Bourgonjon et al., 2010; Groff et al., 2010). Some

students do not find games appealing in general, or

are interested at the beginning but lose interest with

time (Bourgonjon et al., 2010; Groff et al., 2010).

Although the literature provides many examples

and case studies of introducing educational digital

games to the classroom, there is still a lack of

experimental and empirical research that examines

the applicability of these tools in a classroom

environment, and that examines their success on

student motivation and learning outcomes (Huizenga

et al., 2009; Mifsud et al., 2013; Williamson and

Futurelab, 2009). This paper seeks to fill this gap, by

investigating the role and impact of Brain Race (BR),

a customized mobile game-based learning tool, on the

learning and teaching experiences of students and

teachers in a community adult English literacy

program in Qatar. The paper examines the

implementation process of introducing BR in a

classroom, the interaction of teachers and learners

with BR and their opinions on BR, and BR’s

perceived impact on learner motivation, engagement,

and learning outcomes. The game was tested on South

East Asian adult migrant workers participating in an

English community literacy program in Qatar. Not

only are we contributing to the literature by studying

the impact of BR in a classroom environment, we are

specifically shedding light on the impact of BR in a

non-traditional non-formal classroom environment,

where university students teach adult learners as part

of a community program. Moreover, this paper

presents a mobile game-based tool that was

customized specifically to the learning needs and

interests of the target adult migrant worker

population.

3 BACKGROUND

3.1 Language Bridges Literacy

Program Context

Qatar is a small country in the Arabian Peninsula, and

is a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

According to Qatar Statistics Authority and Qatar

Information Exchange, the estimated current

population is 2.2 million, of which foreign workers

comprise more than 94% of the economically active

population. Many of these foreign workers come

from South East Asia to work mainly as construction

workers or in the service industry.

Language Bridges (LB) is a student-led club that

runs the Reach Out to Asia Adult English Literacy

(RAEL) Program, a community English literacy

program that is sponsored by Reach Out To Asia, a

key non-profit organization in Qatar. Carnegie

Mellon University in Qatar (CMUQ) faculty and staff

assist the LB student board in running the program.

LB is mainly composed of CMUQ undergraduate

students who volunteer to teach adult migrant

workers English.

The student teachers come from a variety of

countries, including Qatar, Pakistan, Egypt, India,

and Bangladesh. Most of the teachers interviewed

study Computer Science, Information Systems,

Business Administration, and Biological Sciences.

There are also Northwestern University in Qatar

(NUQ) student teacher volunteers majoring in

Journalism. Most of the teachers are not native

English speakers themselves, and a few of them speak

Urdu and Hindi, which are languages that the learners

are familiar with.

The adult learners mostly work in the CMUQ

building as janitorial staff, service attendants,

contractors, security guards, and technicians. They

are between eighteen to fifty years old, and come

from the Philippines, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. The

Filipino learners have a stronger grasp of English than

Nepali and Sri Lankan learners, and thus usually work

as service attendants. The native languages of the

learners are mostly Tagalog, Hindi, Sinhalese, and

Tamil. RAEL aims to improve learners’ English

literacy. However, the learners are at very different

literacy levels, in both their native languages and

English. As a result, a four-level English curriculum

was designed to cater to the specific literacy needs of

RAEL learners. The program runs in the Fall and

Spring semesters for eight weeks each. The class

levels are divided into Basic, False Beginner,

Intermediate, and Advanced. Some classes are held

once a week for two hours, while the rest are held

twice a week for one hour each. Class size varies from

three to eight learners, with two to three teachers per

class.

3.2 Brain Race (BR) Game

BR is a result of a research project that aims to

investigate the extent to which computing technology

can enhance English literacy skills. The project is a

joint collaboration between researchers in Carnegie

Mellon Univeristy (CMU) in the U.S. and its branch

campus CMUQ. RAEL participants were selected as

a target population because they are learners of

English. The research team conducted a needs

assessment with RAEL learners in January 2013 to

collect information on the English literacy needs of

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

36

this population, and the computing tools that could

potentially enhance their literacy skills. Interviews

were conducted with the learners before they started

their literacy classes. Forty-four learners were

interviewed: sixteen from Sri Lanka, eleven from the

Philippines, thirteen from Nepal, and four from India.

Most participants were between twenty and thirty-

two years old. Only five females participated in the

study.

The needs assessment interviews revealed that

learners want to improve their English skills to be

able to communicate better, to seek better jobs, to

communicate at work, and to lead an easier life in

Qatar. In general, all learners want to develop and be

able to use English grammar. We found that for

beginner learners, an intuitive game with few

instructions would work best for them. For example,

they claimed to enjoy the game Snake, where the

player has to manoeuvre a snake to gobble up an

object. A popular game idea that came from the

learners was a car racing game, where the player can

control the direction and speed of the car. More

advanced English learners informed us that they

enjoy playing sports games, such as basketball and

volleyball, during their free time. Additionally, they

enjoyed more complicated games, such as Sudoku,

Text Whiz (a word game that requires you to build

words with a given set of letters and also tests you on

vocabulary). As shown in Figure 1, Snake and Car

Racing were the most popular game choices.

Figure 1: Game suggestions based on learner preferences.

Based on the needs assessment, the research team

decided to design a car driving game (see Figure 2) so

that it appeals to all learners. BR is a unique game

because it is a customized teaching and learning tool.

The game developers were CMU students who were

part of a class taught by one of the research members.

The class focuses on designing technology tools for

social development purposes. The students designed

BR, a car driving game where players must correctly

answer grammar/vocabulary multiple choice

questions in order to collect fuel for their car. The

obstacles in the game are other cars on the road that

players would have to avoid. The game has power-

ups, such as speed controls and coins, to help the

players obtain a higher score. Every time the player

drives through a fuel icon, a question pops up that

they would have to answer in order to continue

playing. Similar to an endless running game such as

Temple Run or Subway Surfer, the game continues

until the player runs out of fuel or crashes the car too

often. When the game ends, players are prompted to

insert their names to view their scores as well as the

other players’ recorded high scores.

Figure 2: Screenshots from BR game.

4 METHODOLOGY

From our needs assessment, we found that False

Beginner and Intermediate students would benefit the

most from this game. Basic learners would struggle

with the touch screen and the language of the game,

and Advanced learners would find the game to be too

simple. Following this, we scheduled 10-15 minutes

of game sessions in the curriculum of False Beginner

and Intermediate learners. Over the course of eight

weeks, we had six game sessions with the False

Beginner classes, and eight game sessions with the

Intermediate classes. We scheduled fewer game

sessions with False Beginner learners so as not to

overwhelm them.

The structure of the session included members of

the research project visiting the classes on the

scheduled day. The research team was composed of

three of the authors: a Research Associate, and two

Research Programmers, one of whom speaks Hindi

while the other understands Tamil. Access to these

languages helped us communicate with the learners.

We had enough phones for each learner to play

individually, and accessed the BR game through the

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

37

phones’ web browsers. With the help of some student

interns, we developed questions from each level’s

curriculum. To ensure that BR’s educational content

was relevant to what the learners were reviewing in

class, which the literature highlighted was a

contributing factor to the perceived usefulness of such

games (Groff et al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013; Osman

and Baker, 2012; Rice, 2007), questions were either

taken directly from the curriculum, or similar

examples were developed for variety. At the

beginning of the game sessions, we helped the

learners get started with the game, provided

assistance when necessary, and then stepped back to

observe the learners playing, only interacting with

them if the learners were stuck with the game.

Afterwards, we asked the students questions about

what they thought of the game, whether or not they

liked it, and why/why not. We then collected the

phones and left for the classes to resume. Most of the

game sessions happened at the beginning of class.

However, sometimes, due to scheduling conflicts or

simultaneous classes, game sessions happened

towards the end of class.

We relied on qualitative research methods to

examine the process of introducing BR in a

classroom, the interaction of teachers and learners

with BR and their opinions on BR, and BR’s

perceived impact on learner motivation, engagement,

and learning outcomes. First, we observed the

learners and teachers during each game play session.

We occasionally asked the learners questions about

the game after they were done playing. Our

observations took place when classes were in session.

We started the observations when classes commenced

in September 2013. Second, we relied on one-on-one

interviews with twelve out of twenty-six teachers who

have interacted with BR so far. We made sure that

we interviewed teachers who had various exposures

to the games (e.g. some have only seen the game

once, while others have seen it five to seven times).

Teachers were asked to describe what they did while

their learners played, what they thought about BR, the

game session structure, the game being played on a

phone, etc. They were also asked to give their opinion

on whether we should continue including BR or other

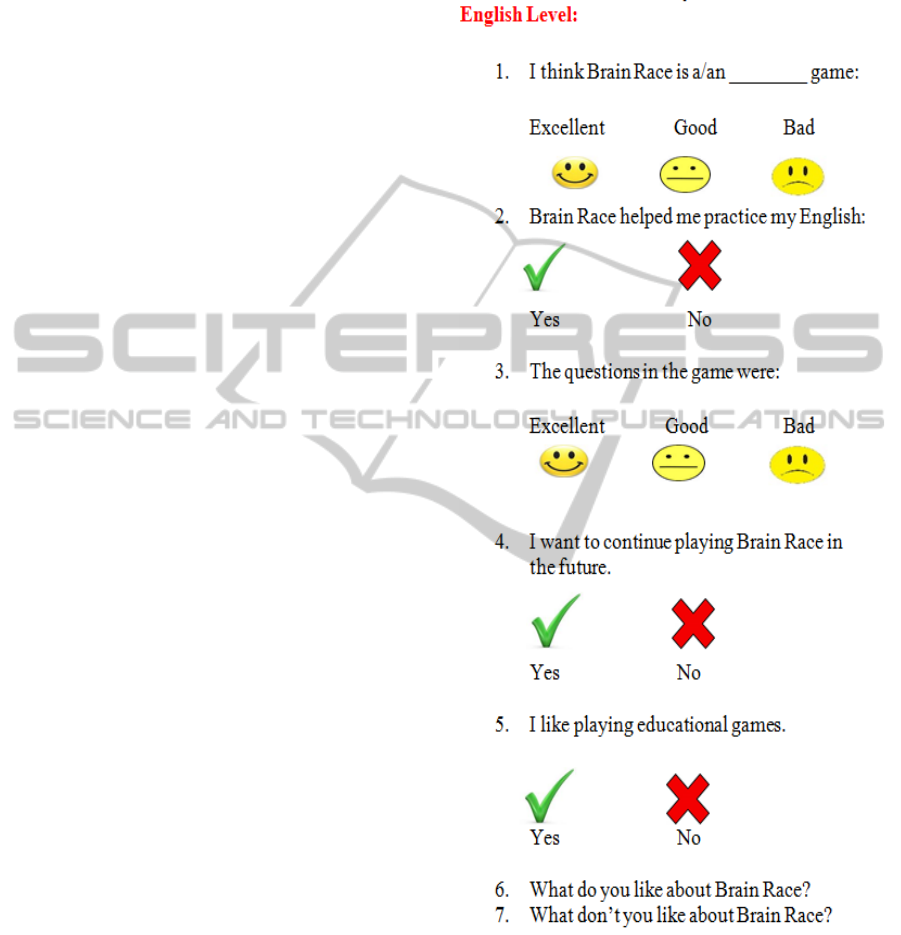

educational games in the curriculum. Third, we asked

learners to complete simple anonymous surveys (see

Appendix) regarding their opinion on the game, what

they liked and disliked about it, and whether they felt

it helped their English. The surveys were explained in

the learners’ native languages by research team

members and student interns. Twenty four learners

responded to the survey out of almost forty learners

who played BR since September 2013. The teacher

interviews and learner surveys were completed

between October-November 2014.

The investigation revealed that although BR

motivates learners and allows them to practice

English concepts, certain issues, such as equipment

used, scheduling, and content relevance, must be

addressed in order to make the experience more

efficient and valuable to both teachers and learners.

The paper argues that learners and teachers have a

variety of preferences, and thus it is important that

they are able to decide for themselves how they want

to include game-based learning tools, such as BR,

into their classrooms. After describing our results in

more detail, we conclude with recommendations to

improve the implementation process so that learners

can benefit more from BR and similar games.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Teacher Interactions with BR

Our observations of game sessions revealed that when

teachers interacted with the learners while playing,

either to help them with the questions or with the

game, learners were more engaged and more focused

on choosing the correct answers. We found that some

teachers would say encouraging comments, such as

‘Good job!’, or would remind learners about a

particular concept in class, or would even read the

questions out loud with the learners in an effort to

help them. With these teachers, the learners seemed

much more engaged, excited, and focused on the

game.

However, a few teachers were disconnected from

the process. Some would just browse through their

phones, or they would seem completely uninterested

in the session. In these classes, it was always very

quiet and not fun for the learners. It may be that

teachers reacted this way because they did not fully

understand the purpose of the project, or they were

intimidated by our presence, or they simply did not

care. We provide recommendations later on how to

address this matter.

5.2 Teacher Opinions on BR

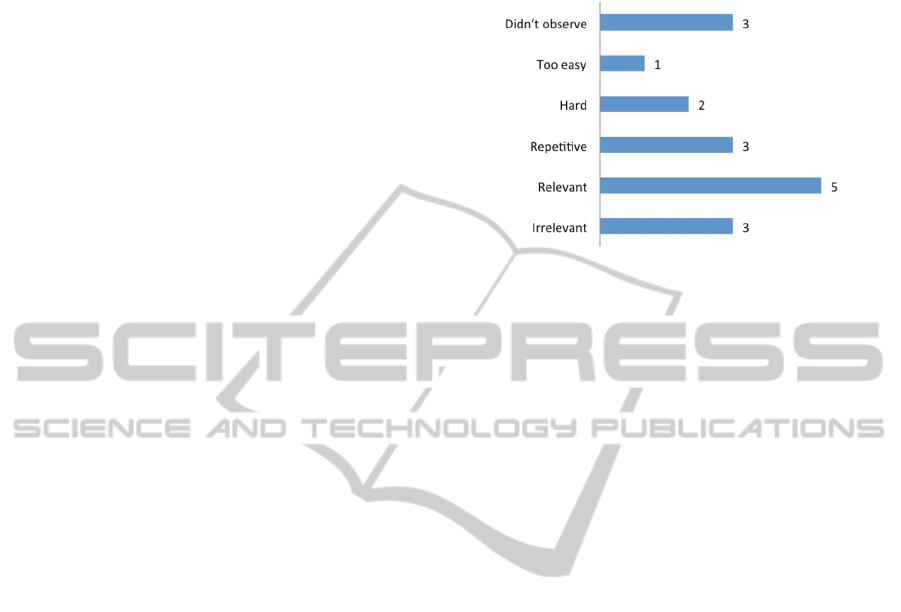

Teachers had mixed reactions about BR itself (see

Figure 3). Most teachers found that BR provided

learners a different learning method to practice

conjugations or to review and reinforce class material

and concepts. One teacher described the game as fun,

stating that he would be interested in playing it to

practice Spanish, a language he is learning at CMUQ.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

38

One teacher thought the game was useful in helping

him evaluate which learner has a good grasp of the

material and which learner needs more help.

Although most teachers thought positively of the

game, a few teachers, some of whom study Computer

Science, noted the following issues about BR: bugs,

abrupt pop-up questions, slow response rate, low

quality, and unattractive graphics.

A few teachers informed us that the learners

requested that the game be provided on their personal

phones, so that they can practice at home and during

their shifts when they have free time. One teacher felt

practicing English concepts using a game was easier

than using their books. We were only able to

accommodate the request to install BR on learners’

personal phones for four learners who owned

smartphones or devices with touchscreens, since they

are required for the game to work properly. The

learners expressed their gratitude for the research

team because they were able to enjoy the game while

practicing their lessons during their free time at work,

particularly when they had Internet access via the

public network.

Figure 3: Teacher opinions on BR game.

5.3 Teacher Feedback on

Implementation Process

5.3.1 Game Session Timing, Length, and

Frequency

As shown in Figure 4, most teachers preferred that

game sessions take place at the beginning of class,

rather than during class, so as not to disrupt their class

flow. One teacher noted that sometimes, he would

forget that a game session was scheduled for a

particular day, and hence would be surprised to see us

coming in during class. The same teacher stated that

in the future, he would like to know exactly when the

team plans to come to the classroom, how long the

game session will last, and what content we will be

including. He stated he would need this information

to provide his class with a brief outline so that they

also know what is happening. A couple of teachers

preferred that game sessions be held at the end so that

their teaching is not interrupted, and also for learners

to practice the concepts they took in class: “I think if

we have [the game session] at the end of class, as a

treat. So have them play after they’ve done the actual

work- so it’s like motivation for them. Something to

look forward to.” One teacher said it would depend

on how much material they needed to cover that

particular day.

Figure 4: Game session timing preferences.

In addition to commenting on their game session

timing preferences, two teachers noted that they want

game sessions to be more frequent, so that learners

could get the most out of the experience. However,

one teacher thought that the sessions should be less

frequent but longer than fifteen minutes. Two

additional teachers similarly thought that the game

sessions were too short and rushed. Hence, the

teachers did not have time to go over the game

instructions, or mistakes learners made in the game.

One teacher was concerned that this made the focus

more on the game rather than the questions. No

teachers found the sessions to be too long.

5.3.2 Using Smartphones

We received a variety of preferences with regards to

where to play the game (see Figure 5). Most teachers

felt smartphones/tablets were better than laptops,

mainly because they were easier to carry around. One

teacher noted that phones were more controllable

because learners could easily and quickly tap the

screen with their fingers, particularly since BR was in

portrait mode. The teacher thought an iPad screen

would be too big for a car game like BR. Other

teachers felt phones were more appropriate than other

devices because learners were more familiar with

them. One teacher specifically discussed how learners

see people play games on their phones all the time,

making the process more relatable than if they were

playing on another device. Almost all learners have

some kind of phone, even if it is not a smartphone. A

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

39

teacher explained that because very few learners have

interacted with a laptop before, it would have been

difficult to train them and it would have overwhelmed

them. Teachers who preferred tablets/laptops felt that

they could monitor learners’ progress better, and that

learners would have better control of the car because

of the bigger screens.

Figure 5: Game technology preferences.

Teachers who chose projector screens felt this

would make the games more exciting as learners

could compete against each other by shouting out the

answers. They felt competition had a positive impact

on class atmosphere. Moreover, this would make the

presence of the research team unnecessary during the

session.

5.3.3 Presence of Research Team

Most teachers found that our presence in their

classroom was intrusive or made the learners feel

tense and uncomfortable (see Figure 6); perhaps

because they felt they were being tested. One teacher

felt that we “took over the whole class,” noting that

sometimes he felt that the research team was “being

kind of a boss on the teachers.”

Figure 6: Teacher opinions on presence of research team.

A significant portion (89%) of the teachers stated

that they would prefer to receive the equipment

before class to lead the game sessions themselves so

that learners are not put off by our presence, and so

that teachers can schedule game sessions whenever

they see fit based on what the learners are learning.

The literature reviewed earlier on the use of

educational games showed how the perceived

usefulness of educational games on the educational

development of students was not always apparent to

the teachers (Groff et al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013;

Rosas et al., 2003; Rice, 2007; Tüzün, 2007;

Williamson and Futurelab, 2009). RAEL teachers

expressed similar concerns, and thus noted that before

they lead the sessions themselves, the research

purpose would have to be explained more clearly, and

the phones would have to be collected immediately

after class so that they are not misplaced. Only 11%

of the teachers stated they would feel more

comfortable having us handle the game session

process: “The team has more authority, [which]

would make the learners feel that the game is useful

and that it is serious. If we do it, they’ll just think that

it’s a game.” Another teacher noted that all the

learners are familiar with us (the research team

members) and hence, there was no negative impact on

the class environment. The teacher noted that it was a

“good change” to have visitors in class.

5.4 Teacher Feedback on BR Game

Impact on Learner Motivation,

Engagement, and Learning

Outcomes

Figure 7: Learner reactions (teacher observations).

Almost all teachers felt that the game had a very

positive impact on the class environment. Most of

them felt that the game brought variety to the class,

and that it was a good break, not from learning, but

from the traditional modes of learning. The game also

made the class more fun, and for some of the longer

classes, teachers felt that it would have reenergized

the learners and made class more exciting.

Most teachers stated that the game got learners to

be excited, and enhanced their class engagement. As

shown in Figure 7, many teachers noticed that

learners remained excited from the moment we

arrived and throughout the session:

They were all excited, would discuss the

questions, their scores. There was more

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

40

engagement compared to when I was teaching

something and had to call on them to answer.

They wanted to play more. Some of them wanted

other games- one of them said cricket. But they

enjoyed it.

A couple of teachers stated that their shy learners

became more talkative and engaged with their

classmates and teachers after the game sessions, “We

had one learner who was very shy and who wouldn’t

talk much in class. He would […] talk to us about the

game because it was something he knew a lot about

because he just experienced it.” Another teacher

noticed that the few learners who did not have phones

of their own were very excited about the game,

whereas the others were more interested in the

questions. One teacher recalled a time when the

learners asked her at the beginning of class if they

were going to play the game today.

However, a few teachers felt that the game session

could have been more engaging, for example, if

learners were placed in teams: “When I play a game

in class, I play it on the board. We complete it

together. But with BR, because of time, there is no

time to make pairs/teams.”

We received a variety of responses regarding the

game’s impact on the learning experiences of the

learners. Four teachers explicitly discussed positive

learning outcomes. Sometimes teachers went over the

mistakes learners made in the game after the game

session was over. Teachers found that the game

helped reinforce key concepts, such as conjugations

and verbs, because learners stopped repeating the

mistakes after playing the game. One teacher recalled

a story that demonstrates learning from the game:

Once I wrote something incorrect on the board. I

wrote a word in the present tense when I should

have written it in the past because I pronounced it

in the past tense. One of the learners corrected me

and told me he remembered this from the game.

We had played the game [during] the previous

class.

Some teachers did not find the game to be as

beneficial as they would have liked. As shown in

Figure 8, teachers found the questions to be

irrelevant, repetitive, or inappropriate for learners’

English levels, which some felt discouraged the

learners. For example, a few Intermediate teachers

noted that the game includes mainly grammar and

conjugation questions, though their curriculum

focuses more on reading passages, job-related issues,

writing resumes and cover letters: “I don’t find BR

beneficial. In the curriculum, they write

compositions, essays, but only grammar is in the

game. The curriculum is all reading. Maybe if I have

more grammar activities in the curriculum, then yes,

so they can relate.”

Figure 8: Teacher opinions on game content.

5.5 Learner Interactions with BR

We were able to obtain learner reactions to BR from

our class observations and conversations with them

immediately after playing, and from the brief survey

we gave them. From our observations of game

sessions since September 2013, we found that

learners enjoyed practicing their lessons using BR.

Some appeared to be more enthusiastic about the

game than others. However, we found that even when

learners reacted indifferently to our arrival with the

games, they almost always chose to play.

Many learners struggled with the touch screen at

first. The biggest struggle for them was figuring out

how to move the car. Some learners tapped the screen,

while others physically tilted the phone thinking that

this movement would make the car move. Eventually,

most had a good grasp of the game rules and the touch

screens. Another struggle was figuring out the

purpose of the power-ups. Some learners avoided all

power-ups thinking they were obstacles. This was

mainly the result of them not reviewing the game

instructions before playing.

When we asked learners how they wanted to play,

most learners chose to play individually. Some

teachers anticipated this was either because they

wanted to compete against each other, or they wanted

to learn alone. Teachers explained that learners

seemed motivated to do well because they were

competing against their classmates. The learners were

almost always quiet during gameplay, while they

focused on answering the questions.

5.6 Learner Opinions on BR

When we would ask learners if they would like to play

the game in the future, they would almost always say

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

41

yes. One learner explained that the game is good

because sometimes, when he is talking to people, he

does not understand what they are saying because he

cannot clearly hear their use of past/present tense. He

found the game useful in that sense. On the surveys,

81% of learners indicated that they wish to play the

game in the future. Moreover, they all indicated that

they like playing educational games. On their

surveys, only one person described the game as bad,

while the rest described it as “good” (ten learners) or

excellent (eleven learners). Ten learners found the

questions to be excellent while twelve thought they

were good. No one found the questions to be “bad.”

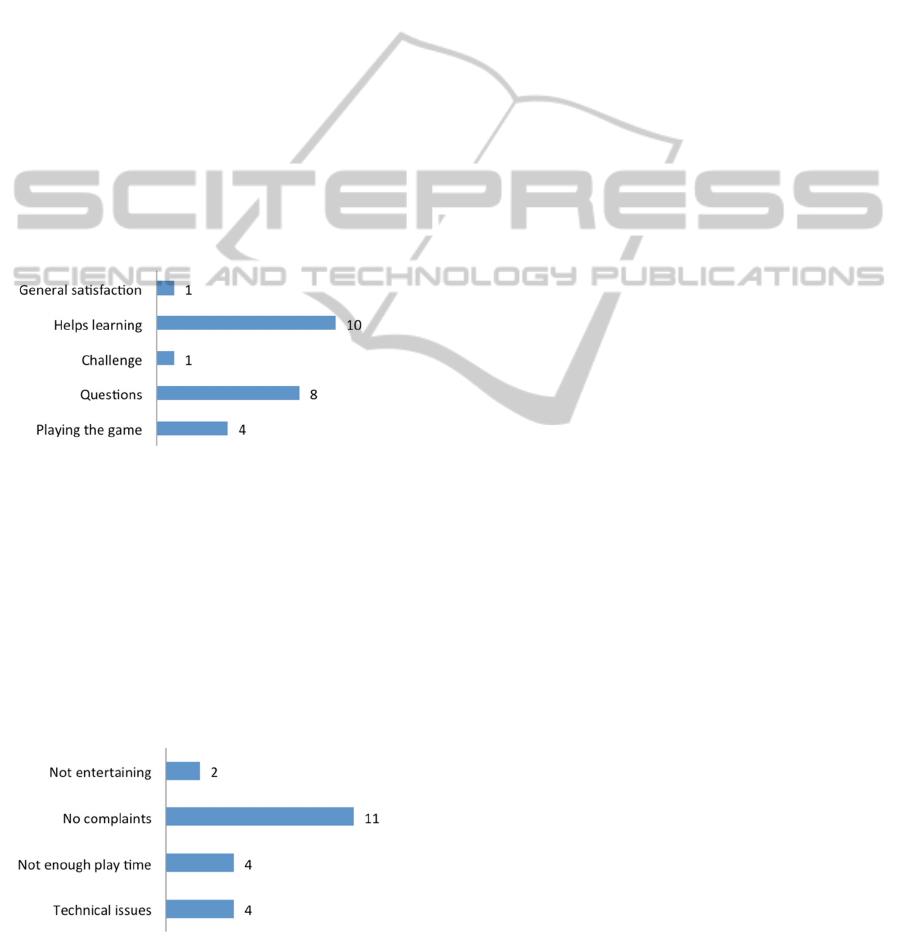

When asked to describe what they liked about the

game verbally, following the game sessions, and in

the survey (see Figure 9), most of them commented

on the learning aspect of the game, noting that they

can practice their English with the questions, “I like

the most in Brain Race is when we answer. Every step

question will be harder, and will be challenging to us.

Fill the answer. That I liked.”

Figure 9: BR aspects learners liked.

Figure 10 demonstrates what learners disliked

about the game. Four learners found the game to be

too short: “The period of time is very short. That I

don't like.” One learner wrote that the game was

boring, while four others commented on some of the

games’ technical issues, such as when it crashes. One

learner indicated that he is not used to phones or

technology in general. Another learner indicated that

he/she would like control keys, which were not

available on the touch screen.

Figure 10: BR aspects learners disliked.

5.7 Learner Feedback on BR Game

Impact on Learner Motivation,

Engagement, and Learning

Outcomes, and Implementation

Process

Occasionally, learners would choose to pair up, so

that one learner is playing, while his classmate helps

him choose the right answer, and then they switch.

One learner said he was discouraged from playing

because he could not get the right answer, so he

wanted to play with someone else. Others stated they

did not want to play but just wanted to answer the

questions. In fact, we noticed that some learners

engaged differently with the games and questions

when they played with a classmate. For example,

there was a female learner who was extremely shy.

She would never ask questions about the game and

tried to figure it out alone. However, when she played

with her classmate, she seemed much more interested

in the game, and helped her classmate with the

questions. In general, game sessions that included

paired learners seemed much more exciting and

collaborative for the learners, especially since they

debated answers.

There were several signs that indicated that

learners were interested in the game and wanted to do

well. For example, sometimes we heard them read the

questions out loud; other times they smiled or nodded

their head in approval when they selected the correct

answer. Other times, they became frustrated when

they selected the wrong answer, and seemed

determined to play again to obtain a higher score.

Sometimes we heard them exchange answers and tips

in their own language. If they obtained a high score,

they smiled in satisfaction and showed off their scores

to us and their teachers. Another important sign is

that, despite the occasional technical issues that came

up during gameplay, learners were always still

interested in playing. Moreover, when we would

announce that the game session was over, they would

almost always continue playing.

However, on a few occasions, one or two learners

from a class would choose not to play, and would

continue working on their assignments. They

explained that either they do not like playing games

and prefer to answer questions only, or that they do

not know how to play, and would therefore also prefer

to answer the questions only. For example, a 50-year-

old learner explained that he has never played a game

before, and so does not know how to nor does he like

playing games. When one of the research team

members played the game in front of him, the learner

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

42

managed to get all the questions right. This supports

the findings in the literature that caution that not all

learners are interested in games or see their

educational benefits (Bourgonjon et al., 2010; Groff

et al., 2010; Rice, 2007; Williamson and Futurelab,

2009). During a different game session, two learners

decided that they did not want to play, but were too

shy to explain why. Their teacher predicted it was

probably because they did not know how to play the

game. In another game session, all the learners in the

class (about three) said they did not want to play the

game that day, and asked us to come back the

following week. The teacher stated that we had come

in the middle of class, when the learners were

working on a reading assignment. The teacher knew

that at least one of the learners really enjoys reading,

which is why he thought the learner was not interested

in playing the game that particular day. This shows

that even if many learners are motivated by the game

and competition, others are not, and prefer to learn the

traditional way.

6 RECOMMENDATIONS

All teachers stated that they would like us to bring BR

back (or any other educational game) into their

classroom. They agreed that games, such as BR,

enhance learner engagement and motivation, and

bring excitement and variety to the class so that it is

not just focused on books and assignments: “In

Spanish, we listen to music, play games. If it’s all

writing and talking to class, it’s so bland and boring.”

Another teacher had similar reactions, and confirmed

what the reviewed literature highlighted earlier with

regards to the importance of introducing relevant

content (Groff et al., 2010; Mifsud et al., 2013;

Osman and Baker, 2012; Rice, 2007):

It makes them think about the material quickly,

they are recollecting what we’ve taught them.

Very helpful- it’s different, it opens their mind to

answering the same questions in different ways, it

helps them process things fast. It’s a fun way of

learning, and should be implemented more.

Another teacher agreed that other educational

tools should be explored further:

I think it’s a good idea. In a lot of educational

settings, we don’t realize that we can use other

sources, and that educational games can be a good

gateway to have them look for themselves at other

materials. It can encourage learners to look for

other ways to learn.

However, a couple of teachers noted that

educational games should be included but with

caution. One teacher cautioned that games can be

helpful only if learners enjoy and/or understand them.

Another teacher explained that games other than BR

can be useful to the learners:

I think they [educational games] are a good idea.

I just don’t think the same game and the same

content is useful, I just felt that they [the learners]

said yes [to playing] so you [the research team]

don’t feel bad. It’s a surprise for the first time. The

game can also be better and happening less

frequently, unless it’s a different game.

Hence, one must not assume that everyone will

enjoy and benefit from educational games. However,

there are several recommendations one can keep in

mind for the future:

Explain to the teachers and learners what the

game is about, what content it will test, and

why it is being introduced into the curriculum.

Ensure that content developed for the game is

relevant to what learners are learning.

Make game sessions longer. Sessions are too

short for learners to interact properly with the

game, and learners should be able to play the

game more regularly. Moreover, longer game

sessions will allow teachers to explain the

game properly and go over mistakes.

Allow teachers to decide whether they want the

research team to lead the game sessions, or if

they want to take the lead on it themselves. If

teachers decide to have the research team lead

the process, schedule game sessions at the

beginning or end of class. If teachers decide to

lead the process themselves, ensure that they

receive the equipment before class.

Present teachers and learners with different

equipment (smartphones, tablets, etc.), so that

they can choose how they want to play.

Ask teachers and learners how often they want

game sessions to be, particularly since some

teachers indicated that they wanted it more

regularly while others preferred it to be played

only a few times.

7 CONCLUSIONS

McClarty et al. (2012) argue that “research should

prioritize how games can best be used for learning”

(p.23). This paper examined the process of

introducing a customized mobile game in a

classroom, the interaction of teachers and learners

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

43

with the game and their opinions on it, and the game’s

perceived impact on learner motivation, engagement,

and learning outcomes. We demonstrated the positive

and negative impacts of BR on adult learners.

Teachers and learners believe that educational games

are motivating and help learners with their English

skills when game play sessions are appropriately

implemented. Although teachers welcomed the

continuous inclusion of BR, or any other educational

game into the class, they (and their learners)

highlighted concerns regarding how the games are

introduced in the classroom. Our main conclusion is

that teacher and learner concerns should be

addressed, while ensuring that they are given a variety

of choices that best meet their needs and interests.

In the next phase of our project, we aim to

improve BR, making it a smoother and more

appealing game based on the feedback we received

from those who have interacted with it. Similar to

other games discussed in the literature (Mifsud et al.,

2013; Shiratuddin and Zaibon, 2010), there are still

technical and quality-design issues we need to

address. Moreover, we are currently investigating the

impact of BR and other mobile-based games on

different populations in Qatar and the U.S., including

postsecondary students, adult refugees, and students

with special needs. Additionally, we are exploring

different tools to allow teachers to see which

questions or academic areas their learners are

struggling with. In general, we are exploring clearer

measures to help us evaluate BR’s impact on learning

outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many individuals supported the work presented in

this publication. This publication was made possible

by the National Priorities Research Program (NPRP)

grant # 4-439-1-071 from the Qatar National

Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The

statements made herein are solely the responsibility

of the authors. We would like to thank Yomna Sabry

for assisting with formatting the document. We would

also like to thank the students participating in the

CMU Pittsburgh class for designing the BR game. We

would also like to thank the ROTA and the LB club

for providing us with access to the learners. And

finally, we would like to express our gratitude to all

the teachers and learners who participated in the

surveys and interviews.

REFERENCES

Bourgonjon, J., Valcke, M., Soetaert, R., and Schellens, T.

(2010). Students' perceptions about the use of video

games in the classroom. Computers and Education,

54(4), 1145-1156.

doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.022.

Dempsey, J. V., Lucassen, B. A., Haynes, L. L., and Casey,

M. S. (1996). Instructional applications of computer

games. Paper presented to AERA’96: The American

Educational Research Association. New York.

Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED394500.

Groff, J., Howells, C., Cranmer, S., and Futurelab. (2010).

The impact of console games in the classroom.

Retrieved from Learning and Teaching Scotland

website:

http://archive.futurelab.org.uk/resources/documents/pr

oject_reports/Console_Games_report.pdf.

Huizenga, J., Admiraal, W., Akkerman, S., and Dam, G. T.

(2009). Mobile game-based learning in secondary

education: Engagement, motivation and learning in a

mobile city game. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 25(4), 332-344. doi:10.1111/j.1365-

2729.2009.00316.x.

Hwang, G., Sung, H., Hung, C., Huang, I., and Tsai, C.

(2012). Development of a personalized educational

computer game based on students' learning styles.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

60(4), 623-638. Retrieved from DOI: 10.1007/s11423-

012-9241-x.

Kam, M., Agarwal, A., Kumar, A., Lal, S., Mathur, A.,

Tewari, A., and Canny, J. F. (2008). Designing e-

learning games for rural children in India: A format for

balancing learning with fun. Proceedings from DIS '08:

The 7th ACM conference on Designing interactive

systems, 58-67. Cape Town, South Africa.

doi:10.1145/1394445.1394452.

Ke, F., and Grabowski, B. (2007). Game playing for maths

learning: Cooperative or not? British Journal of

Educational Technology, 38(2), 249-259.

doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00593.x.

McClarty, K. L., Orr, A., Frey, P. M., Dolan, R. P.,

Vassileva, V., and Mc Vay, A. (2012). A literature

review of gaming in education. Retrieved from Pearson

Assessments website: http://researchnetwork.pearson.

com/wp-content/uploads/Lit_Review_of_Gaming_in_

Education.pdf.

Mifsud, C. L., Vella, R., and Camilleri, L. (2013). Attitudes

towards and effects of the use of video games in

classroom learning with specific reference to literacy

attainment. Research in Education, 90(90), 32-52.

doi:10.7227/RIE.90.1.3.

Osman, K., and Bakar, N. A. (2012). Educational computer

games for Malaysian classrooms: Issues and

challenges. Asian Social Sciences, 8(11), 75-84.

doi:10.5539/ass.v8n11p75.

Papastergiou, M. (2009). Digital game-based learning in

high school Computer Science education: Impact on

educational effectiveness and student motivation.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

44

Computers and Education, 52(1), 1-12.

doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.004.

Qatar Information Exchange (n.d.). Economically active

population (15 years and above) by nationality, sex and

occupation. Retrieved June 17, 2014, from

http://www.qix.gov.qa/

Qatar Statistics Authority (2014, Nov 30). Population.

Retrieved December 5, 2014, from

http://www.qsa.gov.qa/eng/PopulationStructure.htm.

Randel, J. M., Morris, B. A., Wetzal, C. D., and Whitehill,

B. V. (1992). The effectiveness of games for

educational purposes: A review of recent research.

Simulation and Gaming, 23(3), 261-176.

doi:10.1177/1046878192233001.

Rice, J. W. (2007). New media resistance: Barriers to

implementation of computer video games in the

classroom. Journal of Educational Multimedia and

Hypermedia, 16(3), 249-261. Retrieved from

http://www.aace.org/pubs/jemh/

Rosas, R., Nussbaum, M., Cumsille, P., Marianov, V.,

Correa, M., Flores, P., Salinas, M. (2003). Beyond

Nintendo: Design and assessment of educational video

games for first and second grade students. Computers

and Education, 40(1), 71-94. doi:10.1016/S0360-

1315(02)00099-4.

Shiratuddin, N., and Zaibon, S. B. (2010). Mobile game-

based learning with local content and appealing

characters. International Journal of Mobile Learning

and Organisation, 4(1), 55-82.

doi:10.1504/IJMLO.2010.029954.

Tseng, J. C., Chu, H., Hwang, G., and Tsai, C. (2008).

Development of an adaptive learning system with two

sources of personalization information. Computers and

Education, 51(2), 776-786.

doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2007.08.002.

Tüzün, H., Yilmaz-Soylu, M., Karakuş, T., İnal, Y., and

Kizilkaya, G. (2009). The effects of computer games on

primary school students' achievement and motivation in

geography learning. Computers and Education, 52(1),

68-77. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.06.008.

Tüzün, H. (2007). Blending video games with learning:

Issues and challenges with classroom implementations

in the Turkish context. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 38(3), 465-477. doi:10.1111/j.1467-

8535.2007.00710.x.

Virvou, M., Katsionis, G., and Manos, K. (2005).

Combining software games with education: Evaluation

of its educational effectiveness. Educational

Technology and Society, 8(2), 54-65. Retrieved from

http://www.ifets.info/

Wang, Y., and Liao, H. (2011). Adaptive learning for ESL

based on computation. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 42(1), 66-87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-

8535.2009.00981.x.

Williamson, B., and Futurelab. (2009). Computer games,

schools, and young people. Retrieved from Futurelab

website:

http://archive.futurelab.org.uk/resources/documents/pr

oject_reports/becta/Games_and_Learning_educators_r

eport.pdf.

APPENDIX

Brain Race Learner Survey

BrainRace-AnEducationalMobileGameforanAdultEnglishLiteracyProgram

45