T-MASTER

A Tool for Assessing Students’ Reading Abilities

Erik Kanebrant

1

, Katarina Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock

2

, Sofie Johansson Kokkinakis

2

, Arne J

¨

onsson

1

,

Caroline Liberg

3

,

˚

Asa af Geijerstam

3

, Jenny Wiksten Folkeryd

3

and Johan Falkenjack

1

1

Department of Computer and Information Science, Link

¨

oping University, Link

¨

oping, Sweden,

2

Department of Swedish, G

¨

oteborg University, G

¨

oteborg, Sweden,

3

Department of Education, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Keywords:

Reading Assessment, Vaocabulary Assessment, Teacher and Student Feedback.

Abstract:

We present T-MASTER, a tool for assessing students’ reading skills on a variety of dimensions. T-MASTER

uses sophisticated measures for assessing a student’s reading comprehension and vocabulary understanding.

Texts are selected based on their difficulty using novel readability measures and tests are created based on the

texts. The results are analyzed in T-MASTER, and the numerical results are mapped to textual descriptions

that describe the student’s reading abilities on the dimensions being analysed. These results are presented to

the teacher in a form that is easily comprehensible, and lends itself to inspection of each individual student’s

results.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance and teaching effect of finding the

right reading level for each student, i.e. to find the

”zone of proximal development” (ZPD), is a well-

known fact from both a theoretical and an empiri-

cal perspective (Vygotsky, 1976). The task of find-

ing appropriate texts for different groups of students

gets, however, more demanding from grade 4 and on-

wards. To begin with, the texts become longer and

more complex in their structure. Students who have

a reading ability solely adjusted to more simple texts

will get into problem. A little higher up in school

around grade 7, the texts become more and more sub-

ject specific, which is especially visible in the vocab-

ulary. Text structure and vocabulary are, thus, two

very important aspects that can cause problems for

students who are not so experienced readers.

Our long term goal is to support reading for ten to

fifteen year old Swedish students. The means for this

is a tool that assesses each individual student’s read-

ing ability, presents the results to the teacher to facil-

itate individual student feedback, and automatically

finds appropriate texts that are suitable and individu-

ally adapted to each student’s reading ability.

In this paper we present a fully functional tool for

Swedish that presents a profile of a student’s reading

comprehension and vocabulary understanding based

on sophisticated measures. These measures are trans-

formed to values on known criteria like vocabulary,

grammatical fluency and so forth. Four main aspects

of the reading process are in focus in this study; the

student’s reading comprehension, his/her vocabulary

understanding, levels of text complexity, and the sub-

ject area the text deals with. We will first in Sec-

tion 2 present the models of reading upon which the

tests are based, how the tests are constructed and how

text complexity is measured. In Section 3 we present

the experiments that have been conducted this far.

Section 4 presents the actual toolkit and Section 5

presents some conclusions and future work.

2 MODELS OF READING

Common to models of reading in an individual-

psychological perspective is that reading consists

of two components: comprehension and decoding,

e.g. Adams (1990). Traditionally the focus has been

on decoding aspects, but in later years research with a

focus on comprehension has increased rapidly. Some

studies of comprehension concern experiments where

different aspects of the texts have been manipulated in

order to understand the significance of these aspects.

In other studies interviews with individuals or

group discussions are arranged in order to study how

a text is perceived and responded to and how the

reader moves within the text, e.g. Liberg et al. (2011);

220

Kanebrant E., Heimann Mühlenbock K., Johansson Kokkinakis S., Jönsson A., Liberg C., af Geijerstam Å., Wiksten Folkeryd J. and Falkenjack J..

T-MASTER - A Tool for Assessing Students’ Reading Abilities.

DOI: 10.5220/0005410902200227

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 220-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Langer (2011). This last type of studies is very often

based on a socio-interactionistic perspective. What

is considered to be reading is, thus, extended also to

include how you talk about a text when not being

completely controlled by test items. In such a per-

spective it has been shown how students build their

envisionments or mental text worlds when reading

by being out and stepping into an envisionment of

the text content, being in and moving through such

an envisionment, stepping out and rethinking what

you know, stepping out and objectifying the expe-

rience, and leaving an envisionment and going be-

yond (Langer, 2011, p. 22-23). These so called

stances are not linear and for a more developed reader

they occur at various times in different patterns dur-

ing the interaction between the reader and the text,

i.e. the reader switches between reading e.g. ”on the

lines”, ”between the lines”, and ”outwards based on

the lines”.

In a socio-cultural perspective the focus is made

even wider and reading is perceived as situated social

practices. The term situated pinpoints that a person’s

reading ability varies in different situations and with

different text types and topics. A model of reading

as social practice is proposed by Luke and Freebody

(1999). They map four quite broad reading practices

that they consider to be necessary and desirable for

members of a Western contemporary society: coding

practices, text-meaning practices, pragmatic practices

and critical practices. The first two practices could

be compared to what above is discussed as decod-

ing, comprehension and reader-response. The last

two practices on the other hand point to the conse-

quences of the actual reading act, which at the same

time is the raison d’etre of reading: there can be no

reading without having a wider purpose than to read

and comprehend. These practices concern on the one

hand how to ”use texts functionally” and on the other

hand to ”critically analyse and transform texts by act-

ing on knowledge that they represent particular points

of views and that their designs and discourses can be

critiqued and redesigned in novel and hybrid ways”

(ibid p 5-6). A person with a very developed reading

ability embraces all these practices and can move be-

tween them without any problem. He/she is not only

able to decode and comprehend the text but also able

to use what has been generated from the text and to

take a critical stance, all this in order to extend his/her

knowledge sphere. All these perspectives taken to-

gether give both a very deep and a very broad under-

standing of the concept of reading. In order to mark

this shift from a narrower to a much more widened

concept, the term reading literacy is often preferred

over reading, see e.g. OECD (2009, p. 23).

When assessing students reading ability the types

of texts and reading practices tested have thus a much

broader scope today than earlier. It facilitates a more

delicate differentiation between levels of reading abil-

ity. Two well-tested and established studies of read-

ing ability in the age span focused here are the inter-

national studies of ten year old students (PIRLS) and

fifteen year old students (PISA). Both these studies

are based on a broad theoretical view of reading, i.e.

reading literacy. The frameworks of PIRLS and PISA

concerning both the design of tests and the interpre-

tation of results in reading ability levels will there-

fore be important sources and resources for construct-

ing students’ reading ability profile in this study, see

e.g. Mullis et al. (2009); OECD (2009).

2.1 Testing Reading Comprehension

The test of students’ reading comprehension in this

study will include, in accordance with a broad view,

different text types of different degrees of linguistic

difficulty, where the students are tested for various

reading practices within different topic areas. In the

construction of this test at least three degrees of lin-

guistics difficulty will be used. Accordingly at least

three prototypical texts will be chosen per school sub-

ject area. Each of these texts also includes testing dif-

ferent aspects of vocabulary knowledge.

Items testing the following reading processes are

furthermore constructed for each of these three texts,

cf. Langer (2011); Luke and Freebody (1999); Mullis

et al. (2009); OECD (2009): 1) retrieve explicitly

stated information, 2) make straightforward infer-

ences, 3) interpret and integrate ideas and informa-

tion, and 4) reflect on, examine and evaluate content,

language, and textual elements. In accordance with

the procedure used in the international study PIRLS,

these four reading processes are collapsed into two

groups in order to reach a critical amount of data to

base the results on, see below.

2.2 Vocabulary Tests

In assessing the vocabulary knowledge of students,

we have focused on the receptive knowledge of sub-

ject and domain neutral lexical items in Swedish nov-

els. The tests intend to cover a part of the lexical

knowledge divided into ages 10-15 years, in 7 sepa-

rate levels. Each level is represented by tests covering

reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge.

We have used a reliable approach in creating vo-

cabulary tests by compiling text corpora at each level

adapted to the age of the students. These corpora are

then used to generate seven separate frequency based

T-MASTER-AToolforAssessingStudents'ReadingAbilities

221

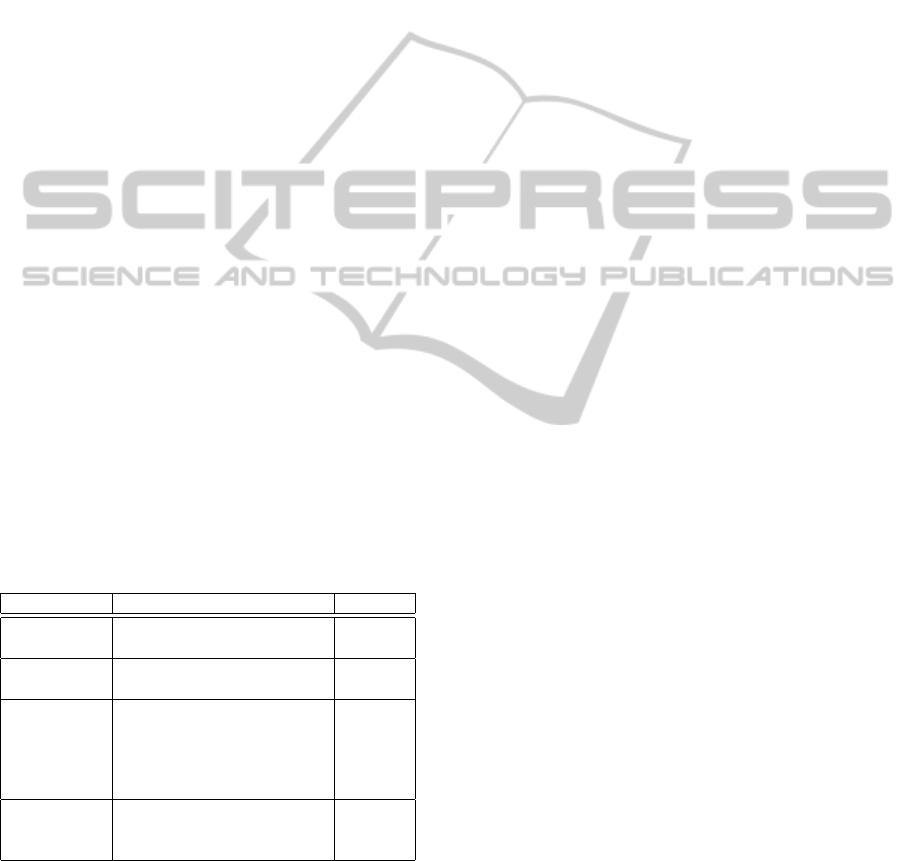

Table 1: A description of subject specific and subject neutral content words.

Word categories Explanation Example (from tests for 10-14 year olds)

Subject neutral words

1. Most frequent The most common words, which could

appear in any text.

Person, sun, run, talk, nice, fast

2. Middle-less frequent Less frequent words above the 2000

most frequent words in age adapted

texts.

Disappointment, realize, decide, desperate,

barely

3. Genre typical (aca-

demic, news etc.)

Academic words in school context,

newspaper genre, descriptive texts

Explanation, development, consider, consist

of, type of, particularly

Subject/domain specific words

4. Every day words

(homonyms)

Words which have a common every day

meaning but also a subject or domain

specific meaning.

Mouth (of a person), mouth (of a river), bank

(of savings), bank (of sand), arm (a body

part), arm (a weapon)

5. Subject typical Words common to a type of text, cf.

natural science.

Motion, radiation, pollution

6. Subject specific Often only appears in one type of text

as unique words, a text in a biology text

book.

Assimilation, digestion, photosynthesis

vocabulary lists.

When studying and analysing vocabulary in texts,

words may be divided into subject-neutral and

subject-specific words. Subject specific words are

known as those words which would typically appear

in texts regarding specific subjects, school subjects or

domains in general. The categories are described in

a further developed category scheme partly inspired

by previous research by Nation (2014); Lindberg

and Kokkinakis (2007); Kokkinakis and Fr

¨

andberg

(2013). Each of these groups can then be divided into

several sub-categories, as described in Table 1.

Words represented in each category are content

words, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

These words are selected since they represent im-

portant parts of the knowledge as opposed to func-

tion words which are used to connect words into sen-

tences. Function words tend not to vary too much and

are normally not perceived as the most difficult words

since they are quite common.

To select test items for the vocabulary test, the fre-

quency based vocabulary list from each level of age is

used as a point of departure. The 2000 most common

tokens, category 1 in Table 1, are deleted from the list

by comparing with other frequency based vocabulary

lists. Then, 50% nouns, 25% verbs, 25% adjectives

and adverbs are selected from that list, starting out

with the most frequent of category 2 in Table 1.

A synonym list of equivalent words and defini-

tions is used to select 15 appropriate test items accom-

panied with 1 correct answer and 3 possible distrac-

tors. Distractors are words other than the correct an-

swer. As many as possible of the distractors are words

similar to the test item orthographically (in writing)

or phonologically (in sound). Previous research has

proven that test takers tend to select distractors with

any of the two similarities when not knowing the cor-

rect answer. Test items are finally composed of the

vocabulary test in context. This means that a sentence

in the text corpus is used to give a better example on

how a test item is used.

2.3 Text Complexity

The traditional way of measuring text complexity and

expected readability is to consider the Flesch-Kincaid

or Flesch Reading Ease measures (Flesch, 1948), or

for Swedish the LIX value (Bj

¨

ornsson, 1968). The

underlying very simplified hypothesis is that short

sentences indicate an uncomplicated syntax, and that

short words tend to be more common and conse-

quently easier to understand. The measures men-

tioned are found to have bearing on entire texts, as

they are based on average counts, but do not suite an

inspection of isolated sentences or on a more scientif-

ically grounded analysis of texts.

The SVIT model (Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock, 2013)

on the other hand includes global language measures

built upon lexical, morpho-syntactic and syntactic

features of a given text. It takes into account linguis-

tic features appearing at the surface in terms of raw

text, but also at deeper language levels. The first level

includes surface properties such as average word

and sentence length and word token variation calcu-

lated with the OVIX (word variation) formula (Hult-

man and Westman, 1977). At the second level we

find the vocabulary properties which are analysed in

terms of word lemma variation and the proportion of

words belonging to SweVoc — a Swedish base vocab-

ulary (Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock and Johansson Kokki-

nakis, 2012). The third, syntactic level, is inspected

by measuring the mean distance between items in the

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

222

syntactically parsed trees, mean parse tree heights,

and the proportions of subordinate clauses and modi-

fiers. Finally, the fourth level, idea density present in

the texts, is calculated in terms of average number of

propositions, nominal ratio and noun/pronoun ratio.

All features taken into account when analysing the

texts in T-MASTER are listed in Table 2. Some of

them are quite straightforward, while others need an

explanation.

The Lemma variation index is a better way to

count the vocabulary variation in a text, as compared

to the OVIX formula. With the LVIX formula, all

word forms of the same lemma are tied together into

one item. For Swedish, being an inflected language,

there are for instance 8 inflected forms of a noun. It is

likely that if a student knows the meaning of the base

form of a given word, the meaning of most of its reg-

ular inflected forms can be deduced. Moreover, it is

calculated with a formula that minimizes the impact

of hapax legomenon, i.e. words occurring only once

in a corpus.

Words considered as Difficult words are those not

present in category (C), (D) and (H) in the SweVoc

wordlist. In category (C) we find 2,200 word lem-

mas belonging to the core vocabulary. Category (D)

contains word lemmas referring to everyday objects

and actions. Category (H), finally, holds word lem-

mas highly frequent in written text.

The syntactic features MDD, UA, AT, ET and PT

refer to properties in the dependency parsed sentences

in the text.

The Nominal ratio is achieved by calculating the

proportion of nouns, prepositions and participles in

relation to verbs, pronouns and adverbs.

Table 2: SVIT features.

Level Feature Abbrev

Surface

Mean sentence length MSL

Mean word length MWL

Vocabulary

Lemma variation index LVIX

Difficult words DW

Syntactic

Mean dependency distance MDD

Subordinate clauses UA

Prenominal modifier AT

Postnominal modifier ET

Parse tree height PT

Idea density

Nominal ratio NR

Noun/pronoun ratio NPN

Propositional density Pr

3 TESTS

We have developed a first series of reading tests with

texts and questions measuring reading comprehension

and vocabulary knowledge. The tests comprise fiction

texts and are expected to match three different levels

of reading proficiency in the 4th, 6th and 8th school

grades respectively. (The same test is used for the

hardest grade i test and the easiest grade i+ 1 test giv-

ing seven levels in total.)

The tests were carried out in a total of 74 schools

and more than 4000 students in three different cities

in Sweden. The size of a class is around 20 students,

but differs enormously, from as low as 5 students to

more than 40 in one class. Each student did a series of

three tests, with texts and vocabulary on three levels

of difficulty. The tests were conducted in the grade

order 6, 4 and 8.

3.1 Initial Text Selection

Twenty-two texts from the L

¨

aSBarT corpus (Heimann

M

¨

uhlenbock, 2013) and 31 texts from a bank of Na-

tional Reading Tests were examined both qualita-

tively and quantitatively. They were all manually

checked with regard to subjects and choice of words,

and texts that could be considered offensive or obso-

lete were discarded. The ambition was to find suit-

able portions of narrative texts depicting a sequence

of events that would allow construction of test ques-

tions.

After the initial filtering, 6 texts from the L

¨

aSBarT

corpus were selected for the 6th grade, and 8 texts

from a bank of national reading tests for grades 4

and 8. The texts varied in length between 450 and

1166 words and were graded into levels of diffi-

culty after multivariate analysis with the SVIT model.

Earlier experiments showed that for the task of dis-

criminating between ordinary and easy-to-read chil-

dren’s fiction, linguistic feature values at the vocabu-

lary and idea density levels had the highest impact on

the results of automatic text classification (Heimann

M

¨

uhlenbock, 2013). We therefore chose to reward

the features mirroring vocabulary diversity and diffi-

culty, in addition to idea density, when the metrics did

not unambiguously pointed towards significant differ-

ences at the syntactic level. Based on the SVIT model

we selected 7 texts for use in the first tests that were

later reduced into 6, see below.

3.2 Some Findings

We will not present all results from the experiments in

this paper, only some findings that assess the quality

of the tests.

We find that students perform better on simpler

than on more difficult text, which corroborates the

SVIT model. For the tests conducted in grade 6,

T-MASTER-AToolforAssessingStudents'ReadingAbilities

223

many students acquired top scores and therefore two

of the texts from grade 6 were also used for grade

4 providing a stronger correlation between the stu-

dents’ results and the text’s difficulty. We saw an

even stronger correlation between text complexity, in-

dicated by SVIT, and response rates of the weakest

students, i.e. those whose overall test results were <

2 standard deviations below the average. This ob-

servation held for all three school levels. Given that

the SVIT measures were used as benchmark in the

initial levelling phase, we believe that our findings

strongly support the hypothesis that these measures

are able to grade a text’s complexity and hence read-

ability (M

¨

uhlenbock et al., 2014).

There is, further, a statistically significant corre-

lation between the students’ results on the vocabu-

lary tests and the reading tests for all six levels. This

shows that the tools and theories used to develop the

tests are applicable. Note that the vocabulary test

comprises domain neutral every day words from the

same corpus as the readability texts. The purpose is

to assess a general vocabulary competence.

4 T-MASTER

To conduct the tests and provide feedback we have

developed a tool for teachers that has been distributed

to all teachers with students that did the tests (Kane-

brant, 2014). The tool has only been used once, for

fiction texts, but is currently used for social science

texts and will be used for natural science texts after

which we hope to make it publicly available. It allows

teachers to get results on reading ability for each indi-

vidual student. The tool is password protected to en-

sure that results only can be accessed by the teacher.

The response texts intend to describe the reading com-

prehension competencies and vocabulary knowledge.

There are other assessment systems available for

English

1

. LetsGoLearn

2

is one interactive tool shar-

ing our idea of having students read texts and answer

questions and use that as a basis for the assessment.

The main differences are in how the tests are devel-

oped and texts selected. T-MASTER, for instance,

uses tests that consider contextual issues in more de-

tail and select texts using novel, and complex, read-

ability measures.

The current version of the system supports two

kinds of users, students and teachers. The system

is implemented as a Java web application and is ac-

cessed as a webpage using a web browser. All tests,

1

http://usny.nysed.gov/rttt/teachers-leaders/assessments/

approved-list.html gives one overview

2

http://www.letsgolearn.com

responses and analyses are stored in a database that

allows for easy modification of tests, additional anal-

yses and facilitates security. To gain access to the sys-

tem one must be given login credentials beforehand.

In creating these credentials the user is also assigned a

certain role within the system, either as a student or a

teacher. Every user will use the same login page and

is after submitting their login information redirected

to the part of the system relevant to their role.

The students can use the system to take reading

comprehension and vocabulary tests in order to as-

sess their reading level concerning several different

factors. Each test consists of a text of a certain subject

accompanied by a reading comprehension test and a

vocabulary test. The test forms are presented on the

screen while the text can be supplied on paper or on

the screen. The tests are not supposed to be memory

tests, it is, thus, important to ensure that the students

can read the text over and over again, even if the text

is on the screen.

The teacher can log in to the system to receive

feedback in the form of a generated text describing

the reading level of their students for the specific texts

they have been tested on.

T-MASTER has been used to give feedback to all

teachers that participated in the first test series, which

was done only on paper. Out of 126 teachers 74

(60%), have been using the tool to get student feed-

back. It is not that surprising that not all teachers have

used the tool. Although we do not have data on indi-

vidual teachers, students in grade 6 will not have the

same teacher in grade 7, i.e. the teachers can not use

the result to help a student. Teachers in grade 8 will

only have the students one more year. Teachers in

grade 4, on the other hand, will have the same stu-

dents for another 2 years and we believe that more or

less all of those teachers have used the tool. We also

included a questionnaire asking teachers if they liked

the tool. Unfortunately, only four teachers responded

and needless to say, they liked the tool and found it

easy to use. Currently another 4500 grade 4, 6 and 8

students use it to do the tests in order to automatically

create individual reading profiles.

4.1 Student Perspective

For each subject and school year there are 2-3 diffi-

culty levels. For each difficulty level the student will

read a text and take both a reading comprehension test

and a vocabulary test. Furthermore there are differ-

ent sets of texts for each school year, so student A

will read texts from a different set than student B. The

texts of one set correspond to the same difficulty level

as the texts from another set. At the top of the screen

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

224

Figure 1: Student test page for the reading test. The first

item is an example to illustrate how the students are sup-

posed to fill in the form. The first item, termed Fr

˚

aga 1 can

be translated as: ”Question 1: Whom decides which penalty

to be imposed on someone in society” and the fours possi-

ble answers are (from left to right) ”A police”, ”A judge”,

”A prosecutor”, ”A victim”.

there is a progress bar showing the students progres-

sion in the test set he or she has been assigned.

Each test consists of 10-15 multiple choice ques-

tions where the student can mark one answer, see Fig-

ure 1. When submitting a test the student will receive

a message asking the student whether he or she wants

to have a second look at the answers or to submit

the test. To facilitate receiving complete test sets the

system will prompt the students that there are unan-

swered questions; You have X unanswered questions.

After submitting the first test for a text, the reading

comprehension test, the student will be moved on to

the vocabulary test of that text. After having submit-

ted both tests the student is given the choice to either

log out to continue at a later point or move on to the

next test. This procedure will continue until the stu-

dent has submitted the tests for each of the difficulty

levels he or she is assigned in the current subject. If

the browser for whatever reason is closed during a test

the student will after logging in again be forwarded to

the test after the last submitted one in the series.

4.2 Teacher Perspective

When logging on to the system the teacher will see a

list of all the students of his or her class that have re-

sults stored in the system, see Figure 2. Privacy is im-

portant, especially allowing researchers access to the

results without revealing individual students ID, but

at the same time allowing teachers to monitor indi-

vidual students. Therefore, the list comprises student

IDs only. The teacher will have a list not accessible in

the system where all the IDs are connected to specific

students thus keeping the students’ data anonymous

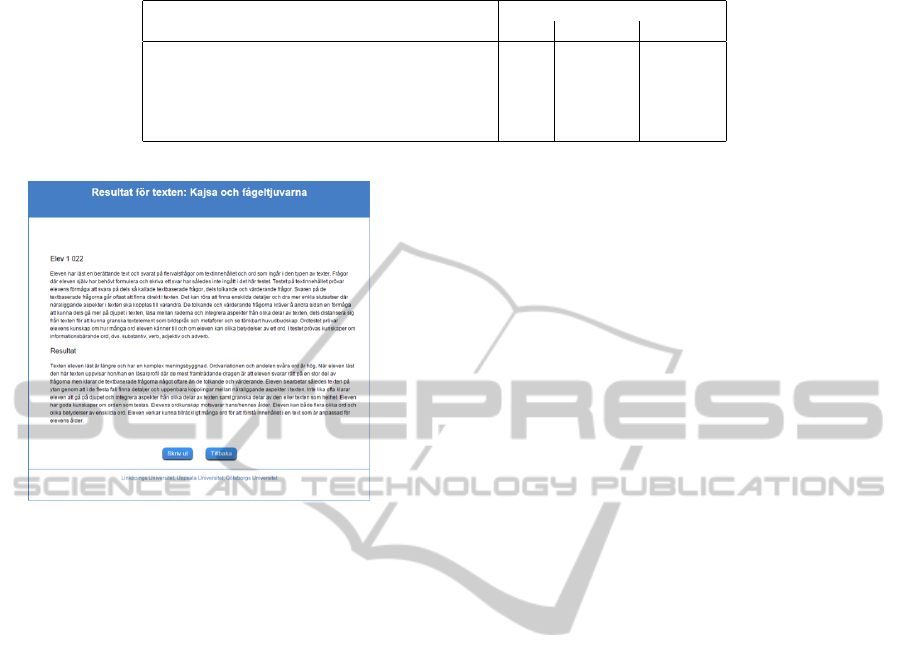

Figure 2: Teacher start up page. The text in the box can

be translated as: ”The students are organised according to

the student ID’s that the teacher gave them when they did

the tests. Only the teacher that can identify an individual

student.” ElevID can be translated to ”Student ID” and visa

resultat can be translated to ”show results”.

in the system.

Clicking on a student’s ID will generate a list of

tests the student has taken. The teacher can then ei-

ther access each result individually or all at once. The

result is presented as a text describing the student’s

performance viewed from several aspects of reading

comprehension and vocabulary capacity, as presented

above.

Each item in the reading comprehension test is as-

signed a certain type of reading process. The system

recognizes the four types of processes used. They are

collapsed into two groups, termed local (retrieve ex-

plicitly stated information and make straightforward

inferences) and global (interpret and integrate ideas

and information and reflect on, examine and evalu-

ate content, language, and textual elements), as de-

scribed above. The reading comprehension scores are

collapsed into five levels. The vocabulary test is sim-

ply scored based on how many correct answers the

student supplied and grouped into three levels.

Thus, our tests can extract five levels of read-

ing comprehension and three levels of word under-

standing, i.e. all in all fifteen different levels for each

subject giving the teacher a very detailed descrip-

tion of a student’s reading strengths and weaknesses.

The fifteen levels of achievement are collapsed into

four achievement levels

3

: 1) (L)ow reading ability, 2)

(Av)erage reading ability, 3) (H)igh reading ability,

and 4) (Ad)vanced reading ability, see Table 3.

The generated feedback consists of two main

parts, see Figure 3. The upper half is a descrip-

tion of the text’s readability level and style as pre-

3

There is a fifth group, D, including those students that de-

viates from what can be expected. They are very few, to-

gether D1 and D2 account for less than 4%.

T-MASTER-AToolforAssessingStudents'ReadingAbilities

225

Table 3: Types of reading comprehension and vocabulary understanding.

Reading comprehension

Vocabulary understanding

Low Medium High

A few questions correct: both local and global L L D1

Half of the questions correct: local > global L Av Av

Half of the questions correct: global > local L Av Av

Most questions correct: local > global D2 H Ad

All global correct and most local D2 H Ad

Figure 3: Excerpt from feedback text.

sented above, Section 2. The lower half, after ”Re-

sultat” comprise three parts: a descriptive text on how

the student handles questions concerning their abil-

ity to retrieve explicitly stated information and make

straightforward inferences, another similar text on the

students comprehension of questions that are oriented

towards interpreting and integrating ideas and infor-

mation and reflect on, examine and evaluate content,

language, and textual elements and finally a text gen-

erated from the vocabulary test score that describes

the students vocabulary. The text in the lower part in

Figure 3 can be translated as:

Results

The text read by the student is long and has a

complex sentence structure. The word variation

and amount of difficult words is high. When the

student has read this text he/she shows a reading

profile where the most prominent features are that

the student answered a large amount of the ques-

tions correctly but manages the text based ques-

tions slightly more often than the interpreting and

reflecting ones. Thus, the student works with the

text more on the surface by mostly finding details

and obvious connections between closely related

aspects in the text. Less often does the student man-

age to go deeper and integrate aspects from other

parts of the text and examine parts of it or the text

as a whole. The student has good knowledge on the

tested words. The vocabulary of the student corre-

sponds to his/her age. The student can many dif-

ferent words as well as different meanings of single

words. The student seems to know enough words to

understand the content in a text adapted for his/her

age.

This text is generated based on the scores obtained

by the questions, grouped according to which aspect

they cover, giving one of the fifteen levels discussed

above.

In the second part of this study, pedagogical rec-

ommendations are also included, adjusted to individ-

ual students’ results (see e.g. Deshler et al. (2007);

McKeown et al. (2009); Palincsar and Herrenkohl

(2002); Shanahan (2014)): For students with low

reading ability, it is suggested that the teacher mod-

els reciprocal teaching. For students with an aver-

age reading ability reciprocal teaching is suggested,

where students successively take more responsibility

in talking about the text. For students with high read-

ing ability, structured talk about a text in groups of

students is suggested. For students with advanced

reading ability, it is suggested that they are given more

challenging texts and therefore may need to take part

in one or all of the above described types of teaching

situations.

Examples of different reading techniques are

given in these recommendations. The teacher is also

urged to observe students’ reading behavior in other

reading situations, and to look for to what degree

students seem to integrate appropriate reading tech-

niques into their reading, and use them as strate-

gies (Goodman, 2014).

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have presented T-MASTER, a tool for automatic

grading of students’ reading abilities along a vari-

ety of reading didactic dimensions. T-MASTER fa-

cilitates teachers’ ability to give individually adapted

support for students by providing a refined picture of

their reading ability along four dimensions: the sub-

ject treated by the text, a text’s difficulty, the student’s

vocabulary understanding and the student’s ability to

engage in various reading processes.

T-MASTER has been used to present reading abil-

ity results to teachers for more than 4000 students

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

226

having read fiction texts and is currently used to con-

duct readability tests for another 4000 students on so-

cial sciences texts.

The toolkit is developed for Swedish and at

present we have no plans on adapting it to other lan-

guages. Given that language specific resources are

readily available, this can easily be done. There are,

for instance, plenty of resources for English making it

easier to analyse language complexity.

Future research includes developing a module that

analyses texts in a subject area according to the SVIT

measures and suggests texts that have a reading diffi-

culty suitable for an individual student based on their

results on the test.

REFERENCES

Marilyn Jager Adams. Beginning to Read. Thinking and

Learning about Print. Cambridge, Massachusets &

London, England: MIT Press., 1990.

Carl Hugo Bj

¨

ornsson. L

¨

asbarhet. Liber, Stockholm, 1968.

Donald D. Deshler, Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar, Gina

Biancarosa, and Marnie Nair. Informed Choices

for Struggling Adolescent Readers: A Research-

Based Guide to Instructional Programs and Prac-

tices. Newark DEK: International Reading Associa-

tion, 2007.

Rudolph Flesch. A new readibility yardstick. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 32(3):221–233, June 1948.

Yetta M. Goodman. Retrospective miscue analysis: Illumi-

nating the voice of the reader. In Kenneth S. Good-

man and Yetta M. Goodman, editors, Making Sense

of Learners, Making Sense of Written Language: The

selected works of Kenneth S. Goodman and Yetta M.

Goodman, pages 205–221. NY: Routledge, 2014.

Katarina Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock. I see what you mean. As-

sessing readability for specific target groups. Disser-

tation, Spr

˚

akbanken, Dept of Swedish, University of

Gothenburg, 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/32472.

Katarina Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock and Sofie Johans-

son Kokkinakis. SweVoc - a Swedish vocabulary

resource for CALL. In Proceedings of the SLTC 2012

workshop on NLP for CALL, pages 28–34, Lund,

2012. Link

¨

oping University Electronic Press.

Tor G. Hultman and Margareta Westman. Gymnasistsven-

ska. LiberL

¨

aromedel, 1977.

Erik Kanebrant. Automaster: Design, implementation

och utv

¨

ardering av ett l

¨

aroverktyg. Bachelors thesis,

Link

¨

oping University, 2014.

Sofie Johansson Kokkinakis and Birgitta Fr

¨

andberg.

H

¨

ogstadieelevers anv

¨

andning av naturvetenskapligt

spr

˚

akbruk i kemi

¨

amnet i timss. [language use in nat-

ural science in chemistry in timss.]. Utbildning &

Demokrati, 3, 2013.

Judith A. Langer. Envisioning Knowledge. Building Liter-

acy in the Academic Disciplines. New York: Teach-

ers’ College Press., 2011.

Caroline Liberg,

˚

Asa af Geijerstam, and Jenny Wiksten

Folkeryd. Scientific literacy and students’ movabil-

ity in science texts. In C. Linder, L.

¨

Ostman, D.A.

Roberts, P-O. Wickman, G. Erickson, and A. MacK-

innon, editors, Exploring the Landscape of Scientific

Literacy, pages 74–89. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Inger Lindberg and Sofie Johansson Kokkinakis. Ordil - en

korpusbaserad kartl

¨

aggning av ordf

¨

orr

˚

adet i l

¨

aromedel

f

¨

or grundskolans senare

˚

ar [ordil - a corpus based

study of the vocabulary in text books in secondary

school]. Technical report, Institutet f

¨

or svenska som

andraspr

˚

ak, G

¨

oteborgs universitet, 2007.

Allan Luke and Peter Freebody. Further notes

on the four resources model. Reading On-

line. http://www.readingonline.org/research/ lukefree-

body.html, 1999.

Margaret G. McKeown, Isabel L. Beck, and Ronette G.K.

Blake. Rethinking reading comprehension instruction:

A comparison of instruction for strategies and content

approaches. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(3):218–

253, 2009.

Katarina Heimann M

¨

uhlenbock, Erik Kanebrant, Sofie Jo-

hansson Kokkinakis, Caroline Liberg Arne J

¨

onsson,

˚

Asa af Geijerstam, Johan Falkenjack, and Jenny Wik-

sten Folkeryd. Studies on automatic assessment of

students’ reading ability. In Proceedings of the Fifth

Swedish Language Technology Conference (SLTC-

14), Uppsala, Sweden, 2014.

Ina V.S. Mullis, Michael O. Martin, Ann M. Kennedy, Kath-

leen L. Trong, and Marian Sainsbury. PIRLS 2011

Assessment Framework. PIRLS 2011 Assessment

Framework., 2009.

Paul Nation. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language.

Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Joakim Nivre, Johan Hall, Jens Nilsson, Atanas Chanev,

G

¨

uls¸en Eryigit, Sandra K

¨

ubler, Svetoslav Mari-

nov, and Erwin Marsi. MaltParser: A language-

independent system for data-driven dependency pars-

ing. Natural Language Engineering, 13(2):95–135,

2007.

OECD. Pisa 2009 Assessment Framework. Key Compe-

tencies in reading, mathematics and science. Paris:

OECD, 2009.

Annemarie Sullivan Palincsar and Leslie Rupert Her-

renkohl. Designing collaborative learning contexts.

Theory into Practice, 41(1):26–32, 2002.

Timothy Shanahan. To teach comprehen-

sion strategies or not to teach them.

http://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/2014/08/to-

teach-comprehension-strategies-or.html., 2014.

Lev S. Vygotsky. Tænkning og sprog. Volym I & II.

K

¨

openhamn: Hans Reitzel, 1976.

T-MASTER-AToolforAssessingStudents'ReadingAbilities

227