A New Learning Platform using E-textbooks for Socially Networked

Online Learners

Masumi Hori

1

, Seishi Ono

2

, Kazutsuna Yamaji

3

, Shinzo Kobayashi

4

,

Toshihiro Kita

5

and Tsuneo Yamada

6

1

General Manager, Planning Office, NPO CCC-TIES, 7-1-1 Tezukayama, Nara-city, Nara, Japan

2

Vice President, NPO CCC-TIES, 7-1-1 Tezukayama, Nara-city, Nara, Japan

3

Associate Professor, Research and Development Centre for Academic Networks,

National Institute of Informatics, 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan

4

CEO, SmileNC and Co., 2-3-20 Higashimizuhodai, Fujimi-city, Saitama, Japan

5

Professor, Kumamoto University, 2-40-1 Kurokami Chuo-ku, Kumamoto-city, Kumamoto, Japan

6

Professor, Open University Japan, 2-11 Wakaba, Mihama-ku, Chiba, Japan

Keywords: Open Education, Large-scale Online Course, E-Books, E-Learning.

Abstract: Conventional learning management systems that focus on traditional classrooms do not fit many-participant

online courses such as massive open online courses (MOOCs). A learning platform, Creative Higher

Education with Learning Objects (CHiLO) based on e-textbooks aims to develop a flexible learning

environment for large-scale online courses. CHiLO essentially has high portability in electronic publication

3.0 (EPUB3) format as well as a comprehensive open network learning system using various existing

technologies and learning resources, including open educational resources on open network communities,

such as social networking service. We produced a series of CHiLO Books called “Nihongo Starter A1” in

cooperation with the Open University of Japan (OUJ) and the Japan Foundation, and delivered them as a

learning course of OUJ MOOC in Japan MOOC. Our set of experimental outcomes shows that CHiLO

using not Web services but e-textbooks is available for large-scale online courses. The result reveals a

positive completion rate of 22% and active participants posting at 25%.

1 INTRODUCTION

A traditional learning management system (LMS) is

becoming outdated in large-scale online courses

(Sclater, 2008) because LMS provides support for

teaching and learning based on a conventional

classroom although it is an educational support

system at every level, for instance, managing

learning outcomes, learning progress, and

communication between learners. Therefore, a new

LMS with different concepts is required for large-

scale online courses (Mott, 2010).

Our learning platform, Creative Higher

Education with Learning Objects (CHiLO) consists

of components through e-textbooks developed with

a totally new design, considering large-scale online

courses such as massive open online courses

(MOOCs). In this paper, we report the possibilities

for CHiLO in our experiments on Japan massive

open online courses (JMOOCs).

The basic outline of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a brief overview of the current

pedagogical situation. Section 3 presents the

architecture of CHiLO. Section 4 describes our

experimental results. Section 5 discusses some

challenges of CHiLO, and Section 6 is a summary.

2 PEDAGOGICAL SITUATION IN

RECENT YEARS

2.1 Traditional LMSs

In the early 2000s, LMSs became widely used in

higher education, along with the growth of the

Internet (Cross, 2004). Following this generation,

the LMSs we know today, e.g., Blackboard, Sakai,

Moodle, and Canvas, appeared. The typical LMS

comprises course creation and delivery, secure

authentication and enrolment, content management

and delivery, interaction between students, and

512

Hori M., Ono S., Yamaji K., Kobayashi S., Kita T. and Yamada T..

A New Learning Platform using E-textbooks for Socially Networked Online Learners.

DOI: 10.5220/0005444205120519

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 512-519

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

methods of assessment and testing (see

https://docs.moodle.org/27/en/Features).

Such traditional LMSs are designed as course-

centric or time-based systems around content

delivery, course delivery, and mechanics of running

a course (Pitigala Liyanage, Lasith Gunawardena

and Hirakawa, 2013). The course-centric system

faces some challenges such as data analytics and

relationship management for new online educational

methods, including competency-based learning

(Irakliotis and Johnstone, 2014). The conventional

LMS focuses on a traditional classroom; it does not

fit the new educational method. The course-centric

system must be replaced with a learning-based or

competency-based system that is completely aligned

with students and what they need to progress

educationally (Sturgis, 2011).

2.2 Current Pedagogical Situation

As recent online educational trends, learning content

is split into smaller units, which are then

reassembled to allow self-paced and self-path

learning (Force, 2013).

2.2.1 Competency-based Education

Competency-based education (CBE) focuses on

effective short-time learning for adult learners, for

instance, working and self-supporting students, in a

short amount of time.

The following points define competency-based

learning approaches (Sturgis, 2011):

Students advance upon mastery.

Competencies include explicit, measurable,

transferable learning objectives that empower

students.

Assessment is a meaningful, positive learning

experience for students.

Students receive timely, differentiated support on

the basis of their individual learning needs.

Learning outcomes emphasize competencies that

include application and creation of knowledge,

along with the development of important skills

and dispositions.

Western Governors University (WGU) has used

CBE since 1997 (Morrison and Mendenhall, 2001).

In 2012, Southern New Hampshire University

(SNHU), seeing a market opening for an LMS

designed around CBE (Straumsheim, 2014), began

advertising its program nationwide. In the United

States, a number of community colleges provide

CBE (Irakliotis and Johnstone, 2014).

At the same time, CBE is criticized in that

colleges learn a great deal about their students’

competence from grades and test scores but have no

information about students’ creativity and character

(Grant, 2014).

2.2.2 Unbundling of Education

The Task Force on the Future of Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT) Education provided

further insights into the unbundling of education,

deemed to take different roles—such as classrooms,

labs, and mentoring—as modules. A module is

defined by its corresponding outcomes such as the

instruction and assessment for the module. Each

module is re-bundled with competency-based

assessments or new assessment methods, which can

relate directly to measurable outcomes for a class or

module (Force, 2013). The Task Force considers

small private online courses (SPOCS), on edX

provided by MIT, to be nothing more than modules.

The unbundling of education is an innovative

method, and dozens of similar efforts are expected to

appear across the United States in the next 3 to 5

years (Bull, 2013).

2.2.3 NanoDegree

The NanoDegree rendered by Udacity, a for-profit

educational organization or a MOOC platform,

provides learners with a bite-sized bundle of

knowledge and immediate motivation for acquiring

a degree. Furthermore, its curriculum is designed for

acquiring specific business skills for 6–12 months

(10–20 hours/week), for $200 a month. Traditional

higher educational courses often do little to fill the

gap between education and business. Instead, the

evidence so far suggests that online education might

do better in motivating low-income students, unable

to invest time and money into liberal arts education,

if a program relates directly to work. Companies

might be best suited to shape such programs (Porter,

2014). However, the education favored by

companies is also criticized for its lack of emphasis

on liberal arts education (Belkin, 2014)

3 ARCHITECTURE OF CHILO

3.1 Implementation

An e-book has the advantage of being easily carried

in some device such as a mobile phone or tablet PC,

without a network. For learners, therefore, the e-

book provides a study environment—anywhere,

anytime.

ANewLearningPlatformusingE-textbooksforSociallyNetworkedOnlineLearners

513

An e-book standard format, EPUB, is the

distribution and interchange format standard for

digital publications and documents based on Web

standards. EPUB defines a means of representing,

packaging, and encoding structured and semantically

enhanced Web content—including XHTML, CSS,

SVG, images, and other resources—for distribution

in a single-file format (see IDPF

http://idpf.org/epub). EPUB can achieve economies

of scale in design, development, and distribution

(Belfanti, 2014).

The CHiLO, based on e-textbooks, aims to

develop a flexible learning environment for large-

scale online courses. It consists of the following four

components:

CHiLO Books using e-textbooks in EPUB3

format

CHiLO Lectures based on one-minute nano

lectures

CHiLO Badges providing authentication and

certification

CHiLO Communities such as social networking

services (SNS), bulletin boards, and chat rooms

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Implementation of four CHiLOs.

3.1.1 CHiLO Book and CHiLO Lecture

The core component of CHiLOs is CHiLO Books,

which are created in EPUB3 format and have media-

rich content including graphics, animation, audio,

and embedded videos.

CHiLO Lectures comprise videos with scripts,

quizzes, and other learning materials. Videos are

one-minute nano lectures. This concept originated

from an experiment showing that the viewing time

of most online learners is approximately one minute.

A CHiLO Lecture is equivalent to one page in a

traditional textbook. A CHiLO Book includes

approximately 10 CHiLO Lectures and a link to a

comment box allowing the user to post to Facebook.

Furthermore, each page of the book has a link to

quizzes on the material presented. A standard

CHiLO course, comparable with a traditional

university course with one academic credit,

comprises 10 CHiLO Books.

3.1.2 CHiLO Badge

It is difficult to perform indirect assessments such as

those on learning time and academic workload in

large-scale online courses. Although CHiLOs

adopted a direct assessment approach for learning

outcomes, completion of a CHiLO course is

measured in standard course hours corresponding to

academic credits.

Whenever learners complete a CHiLO Book,

they receive a CHiLO Badge, which is a simple

mechanism of outcome assessment in CHiLOs.

When tutors wish to check a learner’s progress, they

simply ask the learner to present the CHiLO Badge.

They do not need to confirm with indirect

assessment tools such as grade books, tracking of

past results, and test scores. CHiLO Badges are

based on open Mozilla badges.

3.1.3 CHiLO Communities

Learning communities called CHiLO Communities

combine open SNS on the Web, such as Facebook

and Twitter, with a forum of LMS. Learners ask

questions, have discussions, and exchange

information about their CHiLO Book.

In a large-scale community, a tutor is incapable

of teaching many learners. A CHiLO Community

consists of many learners and a few tutors called

“connoisseurs” who act as substitutes for teachers. A

learner who studies and completes CHiLO Books in

a specific field can become a connoisseur. The

connoisseur and learner stand on equal ground so

that a connoisseur frequently exchanges information

with learners in their communities.

In a CHiLO Community, learners do not learn

from a tutor but on their own, with CHiLO Books as

the learning materials. In this way, learners are

constantly required to find suitable CHiLO Books in

the community. The CHiLO Community provides

functions of discovering, sharing, aggregating, and

repurposing CHiLO Books for learners using Open

Graph Protocol and Microdata.

4 RESULTS OF

DEMONSTRATION

EXPERIMENT

4.1 Experimental Methodology

We produced a series of CHiLO Books called

“Nihongo Starter A1 (NS A1)” in cooperation with

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

514

the Open University of Japan (OUJ) and the Japan

Foundation, and delivered them as a learning course

of OUJ MOOC in JMOOC: JMOOC “is an

organization that was formed in 2013 with the

cooperation of Japanese universities and businesses

that aims to spread and magnify Japanese MOOCs

throughout the country” (see

http://www.jmooc.jp/en/about/).

NS A1 comprises 10 e-textbooks for learners

who want to study Japanese. A single package of an

e-textbook is equivalent to one lesson. To improve

operability and accessibility for learners, we

developed and provided two types of CHiLO Books,

one an EPUB version and the other a Web version.

The Web versions were simply converted from the

EPUB versions of CHiLO Books.

In the demonstration experiment, learners were

allowed to download all the NS A1 CHiLO Books

(10 books) from August 4 to October 15, and to

participate in a learners group that was opened

on Facebook. In other words, without any particular

procedure of course registration, learners were free

to download the CHiLO Books from the Internet and

were able to learn at their own pace.

However, learners who participated in the

Facebook group were recommended to study these

10 books according to a predetermined or

standardized learning schedule, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Standardized Schedule.

Term Learning Objective

1st week Lessons 1 and 2

2nd week Lessons 3 and 4

3rd week Lessons 5 and 6

4th week Lessons 7 and 8

5th week Lessons 9 and 10

6th–10th week Supplementary classes

4.2 Experimental Results

The learners who downloaded or browsed NS A1

CHiLO Books had access from the United States,

Mexico, Colombia, Malaysia, Australia, Thailand,

and Vietnam—in all 94 countries. Table 2 shows the

number of people participating in the learners’

activities.

Table 2: Numbers of People participating in Each Learner

Activity.

Browsed at least 1 NS A1 CHiLO Book 2033

Participated in Facebook group 1491

Took at least one test 487

Were issued badges at least after one test 331

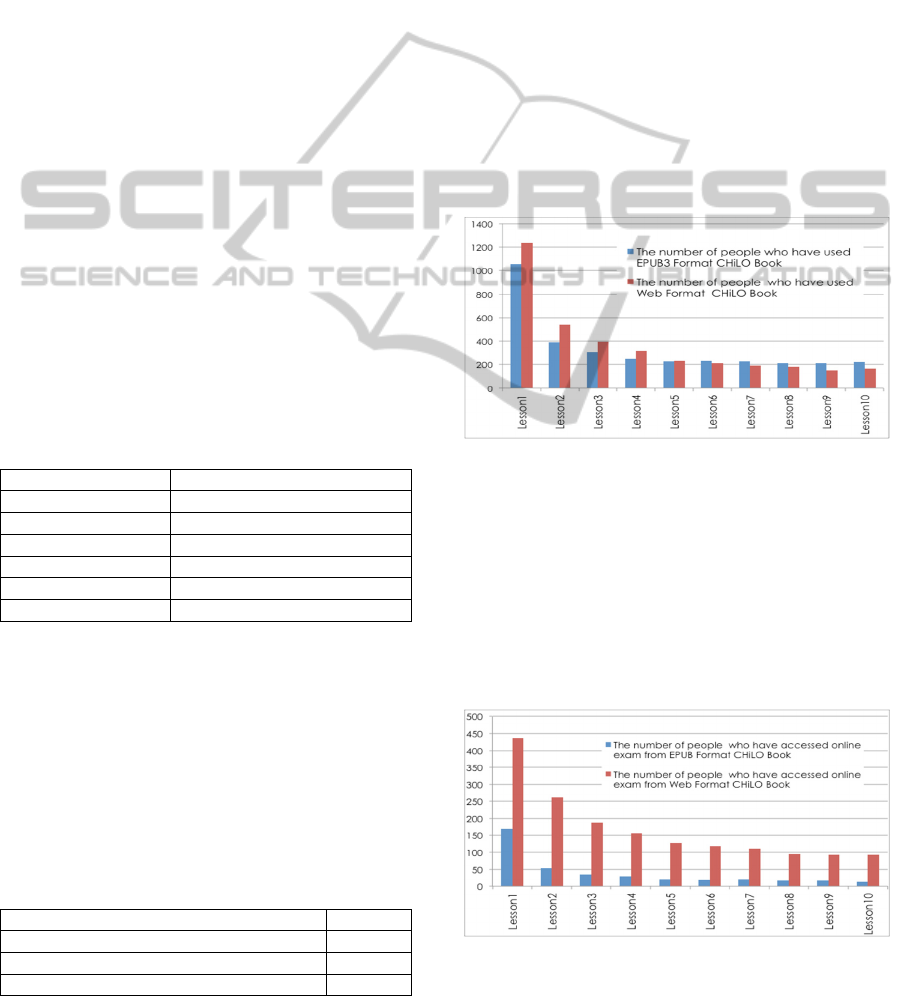

Figure 2 shows which type of format, EPUB3 or

Web CHiLO Books, the learners selected for each

lesson. For all the lessons, the Web format CHiLO

Books were used by 3,624 learners and EPUB

format CHiLO Books were used by 3,336 learners.

Although the number of Web format users was

slightly higher than that of EPUB3 format users, we

assume that the difference is not significant.

As the level of the lessons advanced, however,

the number of EPUB3 format users tended to

exceed that of Web format users. In comparison,

from Lesson 1 to Lesson 10, the number of Web

format users increased by 14% and that of EPUB3

format users increased by 21%.

Furthermore, the fact that the total number of

Web and EPUB format users for Lesson 1 exceeded

“the number of people who have browsed at least 1

NS A1 CHiLO Book: 2,033” as shown in Table 2,

suggests that some learners used both formats.

Figure 2: Number of learners who used EPUB3 format

CHiLO Books or/and Web format CHiLO Books for each

lesson.

Figure 3 shows the number of learners who had

access to online exams from EPUB3 format CHiLO

Books or/and Web format CHiLO Books for each

lesson. For all the lessons, online exams were

accessed by many more learners from Web format

CHiLO Books than from EPUB format CHiLO

Books.

Figure 3: Number of learners who accessed online exams

from EPUB3 format CHiLO Books or/and Web format

CHiLO Books on each lesson.

ANewLearningPlatformusingE-textbooksforSociallyNetworkedOnlineLearners

515

Figure 4 shows specific activities of 1,491

learners who joined the Facebook group. Of the

entire Facebook group, 336 learners, or over 20%,

posted messages. Moreover, 329 learners posted

certain comments responding to these

messages, and 709 learners, or 40% of the

participants in the Facebook group, sent Likes.

Considering that only 1% of users post messages

and only 9% post comments in general online

communities (Nielsen, 2006), learners in this

community were relatively active.

Figure 4: Activities of those who joined the Facebook

group.

Figure 5 shows the number of learners who took

online exams on each lesson and earned badges on

those exams. Of learners who took an online exam

on Lesson 1, 22% completed all 10 lessons and

earned 10 badges.

Figure 5: Number of learners who took online exams and

earned badges on each lesson.

Figure 6 shows the time period when learners

earned their first badges on Lesson 1. We divide the

learners into two groups: “group completed,” in

which learners finished all 10 lessons and earned 10

badges, and “group uncompleted,” in which learners

could not finish the entire course despite earning one

or more, but less than 10, badges. Additionally, we

observed that learners in “group completed” earned

their first badges earlier than those in “group

uncompleted.”

Figure 6: Time period when learners earned their first

badges on Lesson 1.

Furthermore, we compared the two groups in

terms of the time period for earning badges on each

lesson. Figure 7, presenting the result for “group

completed,” shows that learners earned badges

according to the recommended course schedule or

earlier. On the other hand, the result for “group

uncompleted” (Figure 8) shows that learners

increasingly delayed the recommended course

schedule for earning badges as the lessons

progressed.

Figure 7: Time period for earning badges on each lesson in

“group completed”.

Concerning the time period in which learners

completed the entire course and earned all 10

badges, Figure 9 shows that most learners in “group

completed” completed the course within 5 weeks or

according to the course schedule recommended. In

contrast, the other learners took 1 to 10 weeks to

complete the course.

Figure 8: Time period for earning badges on each lesson in

“group uncompleted”.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

516

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Popularity of the Formats

As shown in Figure 2, the number of users of

EPUB3 format CHiLO Books was almost the same

as that of Web format CHiLO Books. However, the

online exams were mainly accessed by the users of

Web Format CHiLO Books, as indicated in Figure 3.

This is presumably because a high percentage of

learners had Internet connection at home and were

familiar with using Web browsers on PCs. Another

possible reason is that Web browsers are easier to

use than e-book readers for online quizzes.

Figure 9: Time period in which learners completed the

entire course.

Table 3: Which CHiLO Book did you use, the EPUB

version or the Web version? (n = 92).

Mostly used Web version 48%

63%

Mainly Web version, sometimes eBook

version

15%

Used both EPUB version and Web

version at the same rate

8%

37%

Mainly EPUB version, sometimes Web

version

14%

Mostly used the EPUB version 15%

Table 4: Why did you use the EPUB version? (Check all

that apply.).

Useful to have it downloaded to my device 32%

Wanted to use it in non-Internet-connected

environment

30%

Interested in the book 16%

Wanted to use the functions within the eBook,

such as bookmark, memo, etc.

9%

No specific reason 4%

Other 9%

According to the survey for learners who

completed all lessons, on the other hand, 37% of the

learners responded that they did use the EPUB

Format CHiLO Books because they could take the e-

books anywhere on their own devices and they could

read them even offline (Tables 3 and 4). From now

on, e-book-based learning will be more common and

useful as an increasing number of people will tend to

learn to use mobile devices. Additionally, highly

accessible EPUB3 e-book readers must be used

more widely for effective learning.

5.2 Learning Community

As indicated by the survey for those in the Facebook

group who completed all lessons, the Facebook-

based learning community was quite active (Tables

5 and 6).

Table 5: How often did you read the comments posted on

Facebook? (n = 92).

Every day 34%

More than 1 day, less than 3 days a week 37%

More than 3 days, less than 7 days a week 21%

Less than 1 day a week 9%

Table 6: Were you satisfied with the activities on

Facebook? (n = 92).

Very satisfied 45%

Somewhat satisfied 39%

Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied 14%

Somewhat dissatisfied 2%

Very dissatisfied 0%

There was a difference between learners in terms

of pace and assignment completion because no

explicit schedule for course enrollment or

assignment submission was announced.

Nevertheless, we observed that learning can occur

where learners with the same objective gather.

The learning community observed here consisted

of less than 1500 people—a small number compared

to a typical MOOC learning community. If a larger

number of people join the community, there will be

difficulties in group activities; therefore, there will

be some need to present an optimal grouping for

learners on the basis of the analysis of learners’

methods and objectives. This will be possible

through development of CHiLO Analytics.

5.3 Scheduling of Learning

Although we did not set deadlines for learners, those

who completed the course tended to progress

according to the standard schedule we presented. On

the other hand, only 30% of learners completed the

course in 5 weeks, as defined in the standard

schedule; the rest (70%) completed the course earlier

or later. In a conventional online course, these

ANewLearningPlatformusingE-textbooksforSociallyNetworkedOnlineLearners

517

learners would likely think that the materials’ levels

were too low, or they would drop out, failing to

complete the course by the deadline.

While there was no course as a learning

framework, indication of a recommended learning

schedule is an important factor for motivating

learners to continue learning, and it is also effective

to indicate the standard learning pace and learning

path. We should also indicate that many learners

who did not complete the course were delayed in

progress on the lessons, compared with the standard

schedule; this suggests that the standard schedule is

not suitable for them. We should manage to provide

learning schedules most suitable for individual

learners by implementing CHiLO Analytics tools.

5.4 CHiLO Analytics, CHiLO

Repository, and CHiLO Reader

We will launch a new component called the CHiLO

Reader. The CHiLO Reader, an e-textbook reader, is

easy to use while studying because it does not

require switching to a browser and supporting

media-rich functions. A Web format is currently

available for CHiLO Books; however, using only an

EPUB format that does not have to switch to the

browser would be better.

The International Digital Publishing Forum

(IDPF) has proposed the EDUPUB format to meet

the requirements of next-generation learning content

based on the e-book EPUB3 format (IDPF, 2014).

However, at present, most e-book readers do not

support the media-rich functions of the EDUPUB

format, for example, embedding videos, JavaScript

compliance, and JavaScript Object Notation (Figure

10).

6 CONCLUSIONS

In general, we obtained positive results in that 22%

of learners who attempted the Lesson 1 examination

completed their learning. The result is fairly good,

considering that the typical completion rate in

MOOCs is said to be less than 10%. However, rigid

comparison is not possible because learners did not

have to declare enrollment when they began learning

in this pilot study.

Furthermore, we observed an interesting

situation: a kind of mutual learning occurred in the

learning community. Learners who had completed

the course tended to provide helpful suggestions to

learners following them.

Figure 10: Developed CHiLO.

Additionally, Spanish-speaking learners

volunteered to form a learning group in which they

translated the NS A1 learning materials into

Spanish. Although the CHiLO project has shown

great development, several challenges persist. One is

that the files used in the e-textbooks are too large to

manage.

The embedded videos in CHiLO Books are small

nano lecture video clips; however, each CHiLO

Book typically includes a combination of graphics,

video clips, online exams, and other components,

which sometimes amount to over 200 files.

Managing individual components and keeping all

the parts up to date is a very complicated task.

Additionally, there is no editing software to create e-

textbooks; therefore, we had to code the sources

from scratch. Thus, creating CHiLO Books takes a

great deal of effort.

Finally, there is a need for an e-text reader that is

easier to use for learning. A Web-based format is

also available for CHiLO Books now, but it would

be better to use only an EPUB-based format that

does not require learners to switch to a Web browser

when they need to access online resources.

REFERENCES

Belfanti, P. (2014). What is EDUPUB. Retrieved August

1, 2014, from http://www.imsglobal.org/edupub/

WhatisEdupubBelfantiGylling.pdf.

Belkin, D. (2014). How to Sell a Liberal-Arts Education.

The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from:

http://online.wsj.com/articles/how-a-college-president-

sells-a-liberal-arts-education-

1413751480?mod=rss_management.

Bull, B. (2013). Ongoing Unbundling of Higher Education

and the MOOC University. Etale - Life and Learning

in the Digital World. Retrieved from:

http://etale.org/main/2013/08/27/ongoing-unbundling-

of-higher-education-the-mooc-university/

Cross, J. (2004). An Informal History of eLearning. On the

Horizon, 12(3), 103-110.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

518

Force, M. T. (2013). Institute-wide Task Force on the

Future of MIT Education: Preliminary Report. Future

of MIT Education. Last accessed, 17, 02-14.

Grant, A. (2014). Throw Out the College Application

System. The New York Times Sunday Review.

Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/05/

opinion/sunday/throw-out-the-college-application-

system.html.

IDPF (2014). EPUB 3 EDUPUB Profile Draft

Specification. International Digital Publishing Forum.

Retrieved from: http://www.idpf.org/

epub/profiles/edu/spec/

Irakliotis, L. and Johnstone, S. (2014). Competency-based

Education Programs versus Traditional Data

Management. EDUCAUSE Review Online. Retrieved

from:

http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/competency-

based-education-programs-versus-traditional-data-

management.

Morrison, J. L., and Mendenhall., R. W. (2001).

Renaissance at Western Governors University: An

Interview with Robert W. Mendenhall. The Technology

Source. Retrieved March, 5, 2009.

Mott, J. (2010). Envisioning the Post-LMS Era: The Open

Learning Network. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 33(1), 1-9.

Retrieved from: http://www.educause.edu/ero/

article/envisioning-post-lms-era-open-learning-

network.

Nielsen, J. (2006). The 90-9-1 Rule for Participation

Inequality in Social Media and Online Communities.

Retrieved from:

http://www.nngroup.com/articles/participation-

inequality/Pitigala Liyanage, M. P., Lasith

Gunawardena, K. S., and Hirakawa, M. (2013). A

framework for adaptive learning management systems

using learning styles. In Advances in ICT for Emerging

Regions (ICTer), 2013 International Conference on

(pp. 261-265). IEEE.

Porter, E. (2014). A Smart Way to Skip College in Pursuit

of a Job Udacity-ATandT ‘NanoDegree’ Offers an

Entry-Level Approach to College. The New York Times

Economy. Retrieved from:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/18/business/economy

/udacity-att-nanodegree-offers-an-entry-level-

approach-to-college.html.

Sclater, N. (2008). Web 2.0, Personal Learning

Environments, and the Future of Learning

Management Systems. EDUCAUSE Center for

Applied Research Research Bulletin, 13(13), 1-13.

Straumsheim, C. (2014). Managing Competency-Based

Learning, Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from:

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/09/29/coll

ege-america-spins-its-custom-made-learning-

management-system.

Sturgis, C., Patrick, S. and Pittenger, L. (2011). It’s Not a

Matter of Time: Highlights from the 2011

Competency-Based Learning Summit. International

Association for K-12 Online Learning.

ANewLearningPlatformusingE-textbooksforSociallyNetworkedOnlineLearners

519