Blended Learning in Project Management

Experiences on Business Games and Case Studies

Mario Vanhoucke

1,2,3

and Mathieu Wauters

1

1

Department of Management Information Science and Operations Management, Ghent University,

Tweekerkenstraat 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium

2

Technology and Operations Management Area, Vlerick Business School, Reep 1, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

2

Department of Management Science and Innovation, University College London,

Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, U.K.

Keywords:

Project Management, Blended Learning, Communication, Integration.

Abstract:

This paper reports on results of experiments in the classroom with students following Project Management

(PM) courses using a blended learning approach. It discusses the impact of communication on the student

performance on business games as well as the advantage of the use of integrative case studies and their impact

on the learning experience of these students. While the performance of students is obtained by marking

their quantitative output on the business game or case exercise, their learning experience is measured through

an analysis of the course evaluations filled out by these students. Diversity among the test population is

guaranteed by testing our experiments on a sample of students with a different background, ranging from

university students with or without a strong quantitative background but no practical experience, to MBA

students at business schools and PM professionals participating in a PM training.

1 INTRODUCTION

Project management is the application of processes,

methods, knowledge, skills and experience to achieve

the project objectives. A project is a unique endeavour

undertaken to achieve predefined planned objectives

within the given network and resource restrictions.

Dynamic Scheduling (Vanhoucke, 2012) is a sub-

discipline of Project Management and focuses on

the quantitative aspects of planning and scheduling,

the analysis of the inherent risk that typifies projects

as well as the monitoring of the project progress

to take corrective actions when necessary. In or-

der to highlight the importance of the integration

of these quantitative aspects, it is also known as

“Integrated Project Management and Control” (Van-

houcke, 2014a). While the Project Management

discipline originates from the chemical plant indus-

try just prior to World War II (Morris and Hough,

1987), it has nowadays found its way in various sec-

tors, ranging from huge construction projects to small

daily operations in the service sector. Consequently,

this growing attention of PM has resulted in the ap-

pearance of courses in the curriculum of almost all

business programmes, both at universities, business

schools and company trainings. This paper will report

on results of a set of experiments done with Project

Management students from various classes and dif-

ferent backgrounds, using an integrative teaching pro-

cess carried out under different settings. This teaching

process is best known as blended learning.

Blended learning is a formal education program

in which a student learns through delivery of content

and instruction via a mix of media and tools, rang-

ing from digital and online media to the use of case

studies and business games. It requires some degree

of student control by the lecturer and often assumes

active participation of the students along the teach-

ing process. In this paper, all experiments are car-

ried out in classes with students following a Project

Management course. The course name differs among

the school and is called “Project Management”, “Inte-

grated Project Control”, “Dynamic Project Planning”

and even “Quantitative Methods for Project Control”,

but regardless of the course name, it always focuses

on an integrated approach of planning and scheduling,

risk analysis and project control, previously labelled

“dynamic scheduling”.

The purpose of this paper is to report on results

and experience of communication experiments using

exercises, case studies and a business game to mea-

sure the impact of these experiments on the learning

Vanhoucke M. and Wauters M..

Blended Learning in Project Management - Experiences on Business Games and Case Studies.

DOI: 10.5220/0005467002670276

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 267-276

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

experience and student results. Through a number

of experiments with students at different universities,

two business schools and in companies, the impact of

various degrees of communication under controlled

settings is tested on both the performance of students

as well as on their learning experience and satisfac-

tion.

2 BLENDED LEARNING

This section gives an overview of the topics discussed

in the Project Management curriculum of Ghent Uni-

versity and Vlerick Business School in Belgium and

University College London in the UK. Its main focus

lies on the quantitative part of the course with a focus

on the previously mentioned Integrated Project Man-

agement and Control. The material used consists of a

mix of tools and methodologies and the correspond-

ing teaching approach can be described as blended

learning. The content of each topic discussed in class

is based on results from numerous research studies

mixed with practical experience. The majority of the

research on Project Management has initially focused

on the scheduling of project activities within the pres-

ence of resource constraints. However, in the last

decade, this research has expanded to its integration

with risk analysis and project control, known as the

Dynamic Scheduling or Integrated Project Manage-

ment and Control methodology. This methodology

has been embedded in the curriculum of Project Man-

agement courses in universities and business schools,

in order to learn how to plan, monitor and control

projects in progress such that they can be delivered

on time and within budget to the client.

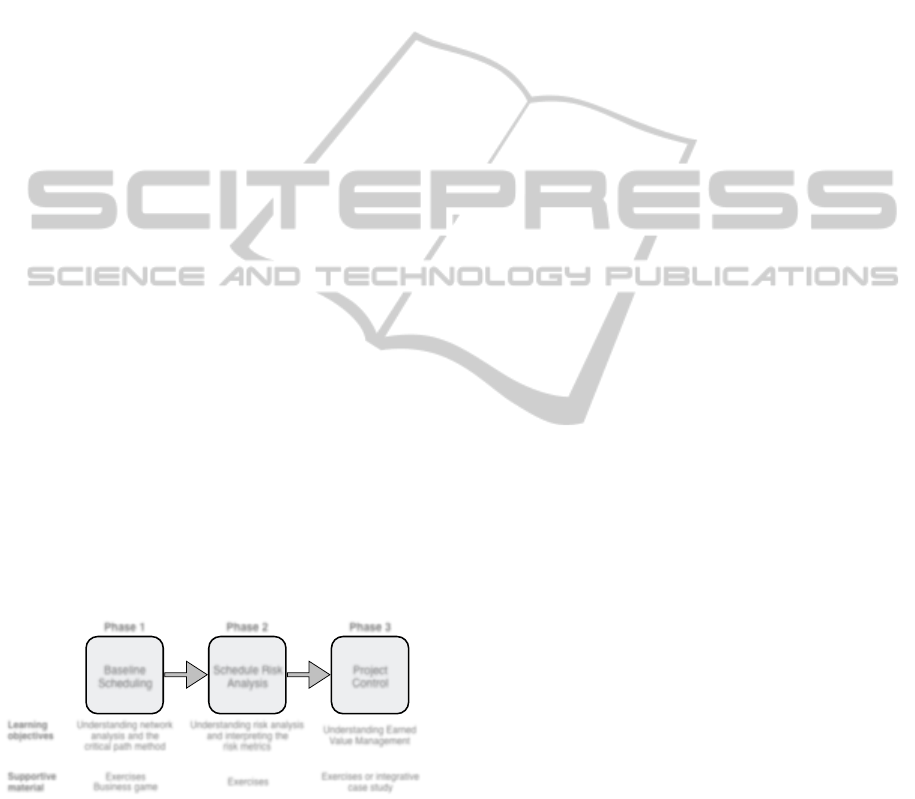

Baseline

Scheduling

Schedule Risk

Analysis

Project

Control

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Understanding network

analysis and the

critical path method

Understanding risk analysis

and interpreting the

risk metrics

Understanding Earned

Value Management

Learning

objectives

Supportive

material

Exercises

Business game

Exercises

Exercises or integrative

case study

Figure 1: Three phases in the PM curriculum.

Figure 1 gives an illustrative overview of the three

main phases of the PM course, which are known as

the baseline scheduling phase, the schedule risk anal-

ysis phase and the project control phase. The figure

also displays the learning objectives as well as the

support material used in the lectures, which will be

discussed in the next sections. First, a brief overview

of the purpose of these three topics is given in the next

section.

2.1 Learning Topics

In this section, the three dimensions of dynamic

scheduling known as baseline scheduling, risk anal-

ysis and project control are briefly outlined.

Baseline scheduling is the act of determining start

and finish times of each project activity within the

activity network and resource constraints and results

in an expected timing of the work to be done as

well as an expected impact on the project’s time and

budget. The research on the resource-constrained

project baseline scheduling problem dates back to

the development of the critical path method (CPM)

and the Programme Evaluation and Review Tech-

nique (PERT) (Kelley and Walker, 1959; Walker and

Sawyer, 1959; Kelley, 1961), and has received huge

attention of academia, leading to a vast amount of

algorithms and tools for resource-constrained project

scheduling problems. Ever since, the research results

on baseline scheduling have been valorized into com-

mercial software tools and integrated project manage-

ment systems and the underlying methods and tech-

niques have taken a central place in the academic cur-

riculum of most Project Management courses. The

main reason is that constructing a baseline schedule

is a crucial step in the dynamic scheduling methodol-

ogy since the project baseline schedule will act as a

point-of-reference for your schedule risk and project

control steps, as discussed hereunder.

Schedule Risk Analysis is a Project Management

methodology to assess the risk of the baseline sched-

ule and to forecast the impact of time and budget

deviations on the project objectives (Hulett, 1996).

Given the knowledge that the construction of a base-

line schedule is a deterministic exercise for prepar-

ing the project progress in a stochastic world, prior

knowledge of the impact of unexpected behaviour on

the project objective is crucial for the project man-

ager and puts the value of the baseline schedule in

the right perspective. The importance of analyzing

the risk of the baseline schedule comes from the need

of any project manager to restrict his/her attention

to the most influential activities of the project that

might have the biggest impact on the initial time

and cost constraints (Vanhoucke, 2010). It enables

the project manager to take a better management fo-

cus and it supports a more accurate response dur-

ing project progress that positively contributes to the

overall project performance. The research on project

risk analysis has been investigated using analytical

methods and fast and efficient Monte Carlo simula-

tions and has quickly found its way into commer-

cial software tools and into the Project Management

teaching curriculum. These tools submit the baseline

schedule to unexpected events and the outcome, pre-

sented as a set of risk metrics, can be used to identify

the most crucial parts in this schedule that require the

most attention during project control, as discussed in

the next and last step.

Project control is the act of monitoring devia-

tions from the expected project progress and control-

ling its performance in order to facilitate the deci-

sion making process in case corrective actions are

needed to bring projects back on track. Both tradi-

tional Earned Value Management (EVM) (Fleming

and Koppelman, 2010) and the novel Earned Sched-

ule (ES) (Lipke, 2003) methods are used. The aca-

demic research on project control has grown rapidly

during the last decade, including the valorization of

academic research results into practical relevance by

bringing together professionals as well as researchers

on the project control topic in workshops and con-

ferences across the world. Efficiently monitoring the

performance of projects in progress and accurately

predicting the final time and cost outcomes in the mid-

dle of their progress is crucial to timely take correc-

tive actions to bring these projects back on track or

to exploit their opportunities. Consequently, the base-

line schedule and the risk metrics of the two previ-

ous steps are only preparatory and support methods to

better take these crucial decisions during the project’s

progress. Controlling projects is therefore the ideal

theme in any Project Management lecture, since it

shows the relevance of the previous two phases to the

students and enables them to translate their gained

knowledge into their daily practice. Thanks to the

growing attention of data analytics and big data, the

interest in monitoring and controlling projects has in-

creased dramatically, resulting in lectures focusing on

using statistical techniques such as process control

charts, multivariate analysis and advanced data ana-

lytics to determine the optimal timing and point of

control to take corrective actions.

2.2 Learning Objectives

The learning objectives of a dynamic scheduling

course are described in the course outline of the cur-

riculum and aim at gradually building up the knowl-

edge to obtain an integrated view on project manage-

ment and control. Therefore, the learning objectives

differ in each phase and a summary is given along the

following lines:

• Phase 1: The main goal is to obtain knowledge

about the network and critical path analysis tech-

niques, as well as to understand the importance of

planning projects for their later progress.

• Phase 2: Understanding the relativity of a de-

terministic baseline scheduling phase within the

presence of uncertainty, as well as understanding

the importance of risk analysis prior to the project

progress is the main goal of this second phase in

the teaching process.

• Phase 3: Learning how to monitor and control

projects in progress using the Earned Value Man-

agement (EVM) methodology is the primary ob-

jective of this phase. This requires that students

are able to interpret risk analysis reports (phase 2)

and use the baseline schedule information (phase

1) as guiding tools for taking corrective actions.

This gradual build-up of learning objectives aims

at reaching an integrative view on the three phases

and the support material discussed next contributes to

the transfer knowledge to obtain a certain degree of

integrative understanding in various ways.

An overview of the standard curriculum of a

Project Management course is given in figure 2. In

general, each session focuses on one or multiple

educational components:

• Instruction: instruction either takes the form of

the classic ex-cathedra classroom session or as an

introduction to a case study or business game.

• Feedback: feedback can occur intermediately or

to conclude a session. During feedback, the expe-

riences of the students are captured and translated

into lessons learned and managerial insights.

• Assessment: assessment evaluates the students on

a number of criteria and is translated into a grade

or a report covering the different aspects of the

solution obtained by the students.

Typically, the course introduces students to Project

Management by teaching network analysis and the

PERT and CPM techniques. Once the concepts of

start and finish times and slack are known, the partici-

pants are armed with sufficient knowledge to tackle

the Project Scheduling Game. Here, they are con-

fronted with multiple trade-off options. An introduc-

tion to the game is given in which the project and the

goal of cost minimization are discussed. At a certain

point in time, the game is paused such that the in-

structor can give some intermediate feedback, allow-

ing participants to adapt their strategy for the remain-

der of the game. When the game has finished, the

participants receive feedback on the pluses and mi-

nuses of following different strategies. The balance

between low costs and high risk provides a segue for

the session on risk metrics and analysis. The solutions

•

Feedback

•

Assessment

FB

A

GameIntroIRiskIAssessmentAFeedbackFBGame

Intro

I

•

Network analysis

•

PERT/CPM

Lecture 1 & 2 Lecture 3: Project Scheduling Game (PSG) Lecture 4 Lecture 5: PSG Extension Lecture 6

Game

Intermediate feedback

Adapt strategy

I

I Instruction FB Feedback A Assessment

Figure 2: Overview of instruction, feedback and assessment throughout the PM curriculum.

of the game are assessed in a quantitative manner,

by comparing costs across groups. After the students

have learned about risk, an extension to the business

game is proposed, in which each participant has a lim-

ited amount of effort (which can be expressed in units

of time, money or a dimensionless unit). After the

game, participants are asked whether they managed

to please the client, the company they work for or

both. The students are assessed by means of a report,

commenting on their individual performance and how

they compare to the other groups. A comparison with

the results of the first business game session is made

as well.

2.3 Support Material

The sequential three-phased teaching approach, each

phase with a clearly defined and different learning

objective, requires that the support teaching material

used to reach these objectives positively contributes to

the performance and learning experience of students

participating in such a teaching process.

The combined use of tools and techniques in a

classroom to stimulate interaction, to improve the

ability of learning and to enhance student satisfac-

tion has been previously described as a blended learn-

ing process and a summary of this support material is

briefly described below. A clear distinction is made

between small exercises, integrative case studies and

business games, as follows:

• Exercises are mainly used ex cathedra in class or

possibly in small teams and require a certain de-

gree of participation by the students by translating

the theoretical concepts into the settings of the ex-

ercise. Exercises therefore mainly focus on only

one phase of the course and have little to no inte-

gration between phases.

• Case studies are mainly used in small teams and

focus on oral communication between the stu-

dents and the lecturer. The use of case studies is

possibly embedded in a problem based learning

mechanism in which the team is responsible for

both lecturing and learning, guided by the teacher.

Unlike exercises, case studies require not a sin-

gle solution approach, but rather aim at solving a

management situation open for interpretation and

therefore typically focus on the integration be-

tween phases.

• Business games: The use of business games is

done to actively involve the student in the teaching

process by making him/her responsible for a sim-

ulated project environment. Through the use of

an interaction between the student and the com-

puter, data is presented to the student in terms

of schedule, risk and control information, which

must be used to make decisions about the future

project progress. In the course, the game that

is used aims at optimizing the timing and costs

of activities, while the computer simulates un-

certain events that harm the initially constructed

baseline schedule. If used in the first phase, it is

the ideal preparation for the second phase of the

teaching process, since it makes the student aware

of the need of risk analysis, which is then dis-

cussed in the second phase. The game is known as

the Project Scheduling Game (PSG) (Vanhoucke

et al., 2005).

It should be noted that the purpose and scope of

this paper is not to give a full overview on blended

learning material in general or its use more specifi-

cally in Project Management courses. Instead, it aims

at testing the impact of communication and integra-

tion using a mix of the previously described support

material in different ways by a set of student exper-

iments carried out over a period of 5 years. More

details on how these experiments have been set up

are given along the following sections. More infor-

mation on the blended learning approach used in the

Integrated Project Management and Control curricu-

lum to enhance student learning and engagement can

be found in (Vanhoucke, 2014b).

3 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

This section describes the settings of the experimental

design in detail. In section 3.1, the student population

is presented as well as the way the data is collected.

Moreover, this section also reviews the importance of

communication within learning in general and within

the three-phased teaching process specifically. Sec-

tion 3.2 then continues with formulating three types of

communication experiments and shows how the out-

come of these experiments is measured and validated.

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Data Collection

The Project Scheduling Game is taught to groups

with and without previous working knowledge. The

last 5 years, approximately 300 people participated in

a commercial training programme, while 175 MBA

students engaged in Project Management as part of

their curriculum. Alternatively, the PSG is part of

the Project Management course for Master students at

Ghent University (Belgium) and the University Col-

lege of London (UK). The game is also rolled out at

two business schools, namely the Vlerick Business

School (Belgium) and the EDHEC business school

(France). 380 students civil engineering and busi-

ness engineering at Ghent University participated in

the PSG, while 41 students at UCL participated in

the game. Lastly, 24 Master students at the business

schools played the PSG. While the participants are

playing the game, log files record which action they

take. These actions consist of changing trade-offs of

activities, viewing the time/cost profile of an activ-

ity or advancing to the next decision period. The log

files enable the people in charge to analyze the perfor-

mance of the participants in detail. For each student

group, a subgroup of approximately 10% of the total

number of students was created for which the commu-

nication was changed. The manner in which a change

to the regular stream of communication was made will

be detailed in section 3.2.1.

3.1.2 Communication

Communication, be it in business, blended learning or

an educational environment, plays a vital role. (Mor-

reale and Pearson, 2008) argue that investing in com-

munication is vital for self-development, turns people

into responsable participants in the world and fosters

success in one’s professional career. (Elving, 2005)

discusses the importance of communication in organ-

isational change. Given the fact that more than half

of all organisational change programs fail, the role of

communication in establishing a community within

an organisation and informing employees about their

tasks and policies cannot be underestimated. Busi-

ness communication has also been studied from an

educational vantage point. (Zhao and Alexander,

2004) identified the short-term and long-term impact

of students that followed a communications course

and queried how the acquired skills benefitted the stu-

dents in their senior years. It was found that the stu-

dents attained good results for tasks involving written

assignments, problem solving assignments, oral pre-

sentations and company reports. (Wheeler, 2007) in-

vestigated the influence of communication technolo-

gies on transactional distance in blended learning and

comments that the future success of blended learning

will rely on the skills and knowledge of tutors, as well

as on technology-mediated communication. In a col-

laborative learning case study, (So and Brush, 2008)

found that the communication medium was a critical

factor in students perceptions of collaborative learn-

ing, social presence and satisfaction. As a result, it is

safe to say that, regardless of the application domain,

investing in communication through blended learning

courses, pays off in the short-term (students become

increasingly apt at communicating their ideas) and in

the long-term (their future careers).

3.2 Research Questions

In this section, the controlled experiments for testing

three different classes of communication experiments

are briefly explained. Moreover, the way in which the

impact of the changed settings in communication on

the learning experience is measured is also outlined.

3.2.1 Communication Tests

Three different classes of communication experi-

ments in the teaching process have been investigated,

as will be explained along the following lines:

Communication Sequence: One of the primary

goals and main advantages of a blended learning ap-

proach is the ability to integrate various ways of

teaching into a combined and sequential process. The

use of various exercises along the phases of the teach-

ing process as a mechanism to test the knowledge of

a student for a single topic in each phase of the course

or the use of an integrative case study to test the stu-

dent’s overall understanding is a choice that must be

made by the lecturer. The diffusion of these exer-

cises along the different phases of the process and

hence, the degree of integration depends on the tim-

ing of the different exercises along the process, grad-

ually translating the lectured concepts into a practi-

cal learning experience. While one prefers an equal

spread of smaller exercises in each phase, another ap-

proach could be to postpone the exercises to the end

of the three-phased learning process, by using an in-

tegrative case study covering the concepts discussed

in the three phases.

Apart from determining the timing and integra-

tion of exercises, the sequence in which the support

material is used is often crucial and determines how

knowledge is built up along the different phases of

the teaching process. In the experiments, the game

has been used in two ways, hereby defining the way

in which the various concepts of the course are pre-

sented to the students.

In a first test, the game is used as a support tool

in phase 1 (see Figure 1) where the student has no

knowledge on risk management. In this default set-

ting, students are responsible for a project in progress

and have to make decisions to optimize time and cost

in a project within the presence of (unknown) un-

certainty. The game tests the knowledge of the stu-

dent on baseline scheduling and serves as the ideal

preparation for the second phase of the teaching pro-

cess where the risk analysis techniques are discussed.

However, in a second game setting, the game is only

used after the second phase in which students now

have a theoretical knowledge about the available tools

and techniques to analyze expected project risk. Con-

sequently, they now play the game with a knowledge

of risk metrics and how they should interpret these

metrics to be better prepared for unexpected events.

The learning by doing experience obtained through

the game is therefore now postponed to phase 2 in-

stead of phase 1.

Communication Format: While the communi-

cation sequence determines the timing and integration

of exercises and business games within the teaching

process, various ways exist to communicate within

a single exercise or case study. In our experiments,

the business game was used to test this idea, since

it involves an interactive approach between the stu-

dent and the computer, and requires that students

make decisions based on a simulated computer out-

put. The way this computer output is displayed on the

screen has been varied from project Gantt chart with

a mainly visual overview but limited information, to

data not well structured, or a table with numbers pre-

sented as risk metrics (risk analysis phase) and con-

trol (project control phase) metrics, or even by using

graphical visualizations of these numbers to facilitate

interpretations and possibly decisions. This experi-

ment aims at testing how the way the data and in-

formation is communicated to the students influences

their decision making process, both in terms of the

final student performance as on their learning experi-

ence.

Communication Expectations: Within the field

of communication, the perceptions of an individual

partly depend on his/her expectations. When the PSG

is first presented, participants are faced with a slightly

larger network in terms of number of activities than in

the previous sessions. The inclusion of multiple ways

in which activities can be executed further enhances

the complexity and the number of choices that can be

made. Consequently, the complexity of the exercise

depends on the project network, the number of activ-

ities and the number of trade-off options for the vari-

ous activities. On the other hand, uncertainty poses a

threat. As the project progresses, some activities will

be ahead of schedule, while others will be delayed.

As a result, the project may deviate from the original

plan. Uncertainty comprises the height and the num-

ber of delays that cause a deviation from the baseline

schedule. In our tests, the nature of complexity and

uncertainty were communicated differently to the par-

ticipants of the game. In the first variant, the aspects

of complexity and uncertainty were downplayed. The

message was given to the students that as in real-life,

the execution would result in changes but it was up to

the individual to decide whether changes due to un-

certainty warranted a change in the time or cost of the

activities. In the second variant, the participants were

made aware of the fact that they would operate in a

highly dynamic environment. The project network

was more extensive than the ones they faced previ-

ously. Additionally, Murphy would come along and

would hinder a proper, on-time execution. Undoubt-

edly, it would be necessary to act and bring the project

back on track. The goal for the participants would be

to decide on the set of activities they would change

and how severely they would crash or prolong project

activities. The consequence of these two variants was

that the expectations of the participants differed dras-

tically.

3.2.2 Output Measures

In order to provide an answer on the three research

questions defined by the three communication exper-

iments, two output measures have been used. A first

quantitative measure is based on the results obtained

by the students, expressed as marks on a test exam as

well as the outcome of a business game (expressed as

the final cost of the project after its finish which must

be as low as possible). A second qualitative outcome

measure is based on an analysis of the students’ eval-

uations filled out after the course that expresses their

satisfaction on the course process as well as their de-

gree of learning.

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

Case Study Exercise

Communication sequence

Better evaluation for case

studies compared to exercises.

0

0.50

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

Civil Engineers Business Schools

Communication format

Graph Table

Civil engineers score better with information

in table format. Business school students

benefit from graphs.

0.9

1.0

1.1

1.2

Complexity Uncertainty

Communication expectations

High Impact Low Impact

Participants assuming Murphy’s presence

would have a severe impact, obtained

better solutions, both from a complexity

and uncertainty point-of-view.

Figure 3: Overview of the main results of the communication experiments.

4 RESULTS

In the next sections, results on the three communica-

tion experiments are described. The results are sum-

marized in figure 3 and are elaborated in the respec-

tive sections.

4.1 Communication Sequence

The timing and integration of exercises along the

phases of the course showed a significant impact on

the learning experience, certainly in terms of student

satisfaction and to a lesser extent in their final per-

formance. Integrative case studies contribute more

to student satisfaction than separate exercises in each

phase and evaluations have clearly shown that integra-

tive case studies help in motivating students to work

harder on the case study. The evaluations not only in-

dicate a higher satisfaction, but also a more intense

learning experience that better converts the various

theoretical concepts into practical relevance. How-

ever, despite this positive effect on the learning ex-

perience, the impact on their final exam performance

was not always clear. While more experienced stu-

dents benefit more from an integrative approach, uni-

versity students without practical experience did not

perform better than using seperate exercises, despite

their higher satisfaction. The mean score of the evalu-

ations of the Project Management course are depicted

in the left panel of figure 3. The y-axis shows the

evaluation of the students, with a minimum value of

1 and a maximum value of 5. The mean score for the

students who received a case study (4.17) through-

out their curriculum was based on 62 evaluations,

whereas 33 student evaluations made up the mean

score for the exercise sessions (4.00).

The results on the two different game settings

came somewhat as a surprise while measuring its

impact on the learning process. The default setting

which assumes that the game is used in phase 1, prior

to the lecture on risk management, has led to a better

learning experience. Students clearly indicated that

an intermediate practical exercise after phase 1 us-

ing the business game clearly allowed them to better

grasp and understand the concepts discussed in phase

1 and to better prepare them for the second phase

of the course. Despite this higher satisfaction, the

results were somewhat lower than the students who

played the game after phase 2. Indeed, the students

who played the game in phase 1 had no knowledge

whatsoever on the risk analysis technique and there-

fore underperformed compared to the student who

had this extra information and played the game af-

ter phase 2. This illustrates that having knowledge

about risk analysis techniques (phase 2) clearly had a

beneficial impact on the decision making process for

optimizing time and cost trade-offs in projects. Al-

though this should not be seen as a big surprise and

only illustrates the relevance of the teaching phases

and the positive contribution of the business game, it

was somewhat unexpected that this better student per-

formance was not related to a higher student satisfac-

tion. Apparently, student performance and the learn-

ing experience and corresponding satisfaction do not

always go hand in hand.

4.2 Communication Format

The experiments clearly revealed that the format of

communication has a significant impact on the tim-

ing of the decisions. It has been observed that more

graphical formats lead to quicker decisions than nu-

merical communication. This has been tested by play-

ing the business game under various restricted time

horizons, which revealed that time pressure has a

more negative impact when using numbers than when

graphical charts are used. Obviously, it is much easier

to interpret graphs and dashboards, while metrics and

quantitative support tables need a thorough analysis

and therefore consume more time.

Surprisingly, the format of communication had no

significant impact on the learning experience and stu-

dent satisfaction since no significant differences in

evaluation could be found between the various exper-

iments using different communication formats. De-

spite this lack of relation between the format of com-

munication and the students’ satisfaction, the perfor-

mance of the students on the game, measured by the

final cost of the project when the game is finished,

depended on the background of the students.

When the engineering university students were

presented with numerical information, they tended to

make the right decision. When the business school

students were presented with the numerical informa-

tion, they underperformed compared to the engineer-

ing students in their decision making, despite their

higher level of experience. However, when the busi-

ness school students were presented with the graph-

ical information, they performed on par with the en-

gineering students who received numerical informa-

tion. This experiment clearly shows that the commu-

nication format is crucial in the teaching process and

defines the quality of decisions made by people. The

results are shown in the middle panel of figure 3. The

y-axis represents the cost deviation obtained by the

students. A division is made between civil engineer-

ing students and students following a business edu-

cation. On average, civil engineers benefit from in-

formation presented in a table format, while business

school students achieve better results with graphical

information. These results are in line with the con-

cepts presented in the book “reinventing communica-

tion” (Phillips, 2014) which discusses the importance

of communication in a professional project manage-

ment environment.

4.3 Communication Expectations

The experiments with regard to the expectations of

the game participants revealed that it is better to err

on the safe side. Participants who assumed Murphy

would come along and that they would have to react

to a highly dynamic and uncertain environment per-

formed better than those participants where the na-

ture of complexity and uncertainty was not empha-

sized. This could be established in the cost deviations

the players achieved and is shown in figure 3. In the

figure’s right panel, the cost deviation when students

assume complexity and uncertainty have a high im-

pact is set equal to 100%. The bar charts indicate that

the costs increase (> 1.0) when complexity and un-

certainty are not deemed to have a high impact. In-

cidentally, the number of trade-off changes and in-

spections of time/cost profiles could be monitored us-

ing the log files. Participants for which the dynamic

and uncertain character of the game was highlighted,

investigated much more alternative courses of action

and dedicated more effort to making changes to the

activities’ durations. Consequently, a relation could

be drawn between the amount of effort invested by

the participants of the game and the attained solution

quality. In general, a higher amount of effort, mea-

sured in terms of the number of trade-off changes and

the inspection of the profile of the trade-offs, leads to

a better solution quality.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper reported on results of a set of students ex-

periments using various ways of communication in

a blended learning process of Project Management

courses. It illustrates how the use of computerized

business games and integrated case studies have a

beneficial impact on the learning experience and stu-

dent performance. However, the way in which this

blended learning methodology is implemented is in-

fluenced by the sequence, format and accuracy of

communication used using exercises, case studies and

business games.

Timing and integration of communication is cru-

cial in the learning process of students and positively

contributes to the learning experience and sometimes

to the student performance. The communication for-

mat has a significant impact on the students’ perfor-

mance and differs along their practical experience and

background. However, no relation could be found be-

tween the format and the satisfaction of students dur-

ing learning. Expectations are also an integral part

of communication. In the final experiment, it was

shown how highlighting the complex and uncertain

nature of the environment can affect the achieved re-

sults. It was found that participants invested more ef-

fort and attained better solutions when the importance

of reacting to uncertainty was stressed. If the decision

on whether a change is desirable was left to the stu-

dents, considerably less effort was put into the evalua-

tion process and a larger cost deviation was the result.

The results of the three experiments are summarized

in table 1.

Obviously, this study suffers from a number of

drawbacks. First, the student population has not been

controlled carefully and has been taken randomly

from an existing pool upon availability. In addition,

the settings of the experiments have been often set

ad hoc and none of the parameters have been care-

fully controlled. The main reason of this drawback

was of a practical nature, since it is hard to put stu-

dents under experiments during learning. We there-

fore opted to change the communication settings on a

Table 1: Overview of the communication experiments and their main findings.

Experiment Main findings

Communication sequence

Integrative case studies lead to higher satisfaction.

Risk knowledge has beneficial impact on decisions.

Communication format

Results depend on previous education.

No impact on learning experience and satisfaction.

Communication expectations

Better expectations of the environment lead to more effort.

More effort leads to better solutions.

small sample of students, often without their knowl-

edge that they experienced a different learning pro-

cess than their colleagues. Finally, the outcome of

the experiments has been measured by an analysis of

student evaluations and exam results and significant

differences could be caused by unknown and uncon-

trolled factors other then the varying settings in the

communication parameters.

However, despite these shortcomings, it is be-

lieved that the student population as well as the time

horizon of these tests is big enough to exclude ran-

domness and to guarantee a certain degree of rele-

vance of the findings of these experiments. Obvi-

ously, more controlled experiments are necessary and

more research in the relation between communication

can and will be done in the future. Three future re-

search avenues are therefore under construction.

More research on the impact of knowledge about

risk management on the quality of decisions made

by students responsible for projects in progress, as

well as an analysis of their behaviour in these uncer-

tain environments is carried out using other experi-

ments. The results of this study have been written

down in a working paper which is currently under

submission in a Project Management journal (Wauters

and Vanhoucke, 2013). In this study, the authors de-

rive solution strategies from participants of the Project

Scheduling Game. The authors tested the time and

cost strategies on a large data set and outlined the cir-

cumstances in which each strategy performs best. It

was found that the cost-based strategy yields the best

results for low penalty environments and networks

counting many trade-off options. In highly uncertain

environments and projects where exceeding the dead-

line is heavily penalized, the time-based strategy per-

forms particularly well. Moreover, a new study is cur-

rently in progress which will extend the experiments

on the timing and sequence of communication. To

that purpose, an extension of the business game will

be presented to the students to formally test and vali-

date whether the first business game contributed to the

learning experience and student performance. Finally,

more studies on communication in Project Manage-

ment are undoubtedly interesting research avenues in

order to find out whether better communication ac-

tually leads to better decisions and a higher project

success rate. These studies are currently in a prema-

ture testing phase using real life data constructed by

(Batselier and Vanhoucke, 2015).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support given by the “Bijzon-

der Onderzoeksfonds” (BOF) for the project under

contract number BOF12GOA021 as well as the sup-

port given by “Fonds of Wetenschappelijk Onder-

zoek” (FWO) for the project under contract number

G009510N.

REFERENCES

Batselier, J. and Vanhoucke, M. (2015). Construc-

tion and evaluation framework for a real-life project

database. International Journal of Project Manage-

ment, 33:697–710.

Elving, W. (2005). The role of communication in organisa-

tional change. Corporate Communications: An Inter-

national Journal, 10:129–138.

Fleming, Q. and Koppelman, J. (2010). Earned value

project management. 3rd Edition. Project Manage-

ment Institute, Newton Square, Pennsylvania, 3rd edi-

tion edition.

Hulett, D. (1996). Schedule risk analysis simplified. Project

Management Network, 10:23–30.

Kelley, J. (1961). Critical path planning and scheduling:

Mathematical basis. Operations Research, 9:296–

320.

Kelley, J. and Walker, M. (1959). Critical path planning

and scheduling: An introduction. Mauchly Asso-

ciates, Ambler, PA.

Lipke, W. (2003). Schedule is different. The Measurable

News, Summer:31–34.

Morreale, S. and Pearson, J. (2008). Why communication

education is important: The centrality discipline in the

21st century. Communication Education, 57:224–240.

Morris, P. and Hough, G. (1987). The anatomy of major

projects: A study of the reality of project management.

John Wiley and Sons.

Phillips, M. (2014). Reinventing communication: How to

design, lead and manage high performing projects.

Gower Publishing.

So, H.-J. and Brush, T. (2008). Student perceptions of col-

laborative learning, social presence and satisfaction

in a blended learning environment: Relationships and

critical factors. Computers & Education, 51:318–336.

Vanhoucke, M. (2010). Using activity sensitivity and net-

work topology information to monitor project time

performance. Omega The International Journal of

Management Science, 38:359–370.

Vanhoucke, M. (2012). Project Management with Dynamic

Scheduling: Baseline Scheduling, Risk Analysis and

Project Control, volume XVIII. Springer.

Vanhoucke, M. (2014a). Integrated Project Management

and Control: First comes the theory, then the practice.

Management for Professionals. Springer.

Vanhoucke, M. (2014b). Teaching integrated project man-

agement and control: Enhancing student learning and

engagement. Journal of Modern Project Management,

1 (4):99–107.

Vanhoucke, M., Vereecke, A., and Gemmel, P. (2005). The

project scheduling game (PSG): Simulating time/cost

trade-offs in projects. Project Management Journal,

36:51–59.

Walker, M. and Sawyer, J. (1959). Project Planning

and Scheduling. Technical Report Report 6959, E.I.

duPont de Nemours and Co., Wilmington, Delaware.

Wauters, M. and Vanhoucke, M. (2013). A study on com-

plexity and uncertainty perception and solution strate-

gies for the time/cost trade-off problem. Working Pa-

per at Ghent University, currently under journal sub-

mission (Check www.projectmanagement.ugent.be for

an update).

Wheeler, S. (2007). The influence of communication tech-

nologies and approaches to study on transactional dis-

tance in blended learning. Research in Learning Tech-

nology, 15:103–117.

Zhao, J. and Alexander, M. (2004). The impact of busi-

ness communication education on students’ short- and

long-term performances. Business Communication

Quarterly, 67:24–40.