Educational Games for Early Childhood

Using Tabletop Surface Computers for Teaching the Arabic Alphabet

Pantelis M. Papadopoulos

1

, Zeinab Ibrahim

2

and Andreas Karatsolis

3

1

Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

2

Carnegie Mellon Qatar, Doha, Qatar

3

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, U.S.A.

Keywords: Educational Games, Tabletop Surface Computer, Language Learning, Modern Standard Arabic, Early

Childhood.

Abstract: This paper presents initial evaluation regarding the use of simple educational games on tabletop surface

computers to teach Kindergarten students in Qatar the Arabic alphabet. This effort is part of the

“Arabiyyatii” research project, a 3-year endeavor aimed to teach 5-year-olds Modern Standard Arabic

(MSA). The paper describes a naturalistic study design, following the activities of 18 students for a period

of 9 weeks in the project. All students were native speakers of the Qatari dialect and they were early users of

similar surface technologies. The paper presents three of the games available to the students, along with data

collected from system log files and class observations. Result analysis suggests that these kinds of games

could be useful in (a) enhancing students’ engagement in language learning, (b) increasing their exposure to

MSA, and (c) developing their vocabulary.

1 INTRODUCTION

Across the Arab world, Classical Arabic (CA), and

its derived form, Modern Standard Arabic (MSA),

used in all formal contexts, is perceived as the

“high” form of language whereas, the local mother

tongues (or “dialects”) are used in daily contexts and

are usually perceived negatively (Ferguson, 1991).

The situation in Qatar is no exception, creating

confusion to students (e.g., Saiegh-Haddad, 2007).

As all diglossic languages, the formal form, MSA is

learned in schools and the informal form, the dialect,

is the mother tongue spoken at home. Thus, the

numbers of geographical dialects are various

(Behnstedt, 2006) if counted by all 22 Arab

countries.

Our work in the “Advancing Arabic Language

Learning in Qatar” project (formerly known as

“ALADDIN” for Arabic LAnguage learning through

Doing, Discovering, Inquiring, and iNteracting, and

recently renamed “Arabiyyatii” for “My Arabic”)

aims at proposing an updated comprehensive

curriculum for the Arabic language – starting from

Kindergarten – that would incorporate up-to-date

didactical methods (i.e., communicative approaches

and collaborative learning) and the use of innovative

educational technology (i.e., tabletop surface

computers).

This research draws extensively upon the works

of Ibrahim (e.g., 2000, 2008, 2009, 2013) pertaining

to Arabs language attitudes, the relatedness of the

MSA to the dialect and the native speakers

awareness, lexical separation as a consequence of

diglossia, the use of technologies in Arabic language

learning, and language planning and education. For

example, in summarizing the current situation of the

Arabic language, Ibrahim (2013) noted that there is

conflict in Arabs towards their language. Native

speakers do not know much about the relationship

between the different varieties of Arabic (dialects)

and the official MSA and they often have trouble

identifying which version is needed from them in

formal education. To make matters worse, the

language teachers often do not receive appropriate

education on how to approach this delicate issue.

The end result, as Ibrahim puts it, is “a native

speaker who is in a life time dilemma” (ibid., p.

360).

The new curriculum tried to address this issue by

applying a holistic approach, offering a rich learning

experience that includes listening, discussing,

writing, storyboarding, and gaming activities. For 9

130

M. Papadopoulos P., Ibrahim Z. and Karatsolis A..

Educational Games for Early Childhood - Using Tabletop Surface Computers for Teaching the Arabic Alphabet.

DOI: 10.5220/0005471701300138

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 130-138

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

weeks during the Fall semester 2013, we tested the

new curriculum in a private Kindergarten of the

Qatar Academy in Doha, Qatar. The instructional

goal during this study period was to teach a class of

5-6 year-olds the Arabic alphabet and enrich their

vocabulary in MSA. The paper focuses on the use of

the educational games, specifically designed and

developed for the project.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 The Arabic Language

The Arabic alphabet consists of 28 consonants, 3

long vowels, and 3 short vowels. Short vowels are

not written within the word, but either above or

below the letter. Arabic writing has four major

characteristics that distinguish it from other

languages: (a) writing is from right to left, (b) most

letters are connected in both print and handwriting,

(c) letters have slightly different forms depending on

where they occur in a word (isolated, initial, medial,

and final form), and (d) Arabic script consists of two

separate “layers” or writing: the first is the basic

skeleton made up of consonants and long vowels,

and the second is the short vowels and other

pronunciation and grammatical markers.

As far as pronunciation is concerned, Arabic has

one-to-one correspondence between sound and

letter, while the writing system is regularly phonetic

meaning that words are generally written as they are

pronounced.

While teaching the Arabic alphabet, we focused

on two major issues: recognition and production of

the letters. Production means that the students

should be able to write and pronounce clearly the

letters of the alphabet, while recognition means

audio and visual recognition. The students should be

able to recognize a specific letter in a spoken or

written word. Production in the project was covered

by writing activities and discussion sessions led by

the school teacher (result analysis on the writing

activities can be found in Papadopoulos, Ibrahim,

and Karatsolis, 2014). On the contrary, the

educational games presented here were focused on

recognition.

2.2 Computer Games in Early

Childhood

The use of computer games in educational contexts

has attracted the interest of many researchers

resulting in a very rich literature. Kebritchi and

Hirumi (2008) provide an overview on the

pedagogical foundations of modern educational

computer games. The use of computer games has

yielded encouraging results in motivation,

engagement, knowledge acquisition, collaboration,

and problem-solving in primary (e.g., Meluso,

Zheng, Spires, and Lester, 2012), secondary (e.g.,

Papastergiou, 2009), and tertiary education (e.g.,

Hainey, Connolly, Stansfield, and Boyle, 2011).

Although there are studies focusing in younger ages

(e.g., Vangsnes, Økland, and Krumsvik, 2012), little

can be found regarding the use of computer games at

Kindergarten. Especially when it comes to the

Arabic context of the project, the use of educational

software or computer games in formal education is

rare, if any.

2.3 Innovative Technologies and

Surface Computers

Tabletop surface computers are a new approach in

learning environments, with research reporting

encouraging results so far. Kerne et al. (2006)

discuss the roles for interactive systems enabled by

touch screen devices in supporting creative

processes and aiding in idea formation. Morris et al.

(2005) examined the educational benefits of using a

digital table to facilitate foreign language learning.

As documented in Piper (2008), the use of

multimodal tabletop displays, as a rich medium for

facilitating cooperative learning scenarios, is just

emerging.

The tabletop surface computers (http://

www.samsung.com/us/business/displays/digital-

signage/LH40SFWTGC/ZA) we use in the project

allowed us to design learning activities using touch

technologies and shared interfaces. The system (also

“table” for the rest) has a 40” touch screen that can

recognize more than 50 simultaneous touch points,

making it possible for several students to interact

and participate in the same activity. The size of the

screen is large enough to support 4 5-year-olds per

table. This was essential in the project, since

breaking apart the traditional setting of a classroom

(i.e., strictly defined by desks and whiteboards) and

allowing students to gather around the tables

increased peer interaction and student participation.

The use of touch technology was essential, since

kindergartners usually lack the ability to use a

computer. On the contrary, the students had already

been exposed to other touch systems, such as

smartphones and tablets both at home (parents’

devices) and at school (each student receives a tablet

pc from the school in the beginning of the year).

EducationalGamesforEarlyChildhood-UsingTabletopSurfaceComputersforTeachingtheArabicAlphabet

131

3 METHOD

3.1 Participants

One of the classes enrolled in the “Arabic Studies”

course was assigned to the study by school

administration. The class had 18 Qatari students (9

boys and 9 girls), natives of the Qatari dialect. All

students were between 5 and 6 years old. Although

students were native speakers of the dialect, they

were novices in MSA. The learning goal of the

course was to teach students fundamental linguistic

skills in MSA such as vocabulary development,

letter production and recognition, and proper

pronunciation.

The total population of the class was available

only 8 days during the course of 9 weeks for various

reasons (e.g., illness). Usually, the actual number of

students in the classroom ranged from 16 to 17.

3.2 Design

The study followed students’ activity in the new

curriculum for a period of 9 weeks (Sep 29 – Dec 4)

and the instructional goal during that period was to

teach students the isolated form of the first 12

Arabic letters (from [ أ ] to [ ز ], considering ‘alif’

and ‘alif with hamza’ two different “letters”). The

design applied in the study followed an naturalistic

study approach.

Usually, a new letter was introduced by the

teacher during the listening and discussion sessions,

followed by writing activities. The games were used

at the end of the class repeatedly, in order to (a) keep

students’ engagement and enthusiasm high, and (b)

enhance retention. To analyze students’ performance

and attitudes, we utilized observations and the

system log files.

3.3 Material

The main instructional goal behind the design of the

educational games was to support students in letter

recognition. In this section, we describe the three

most played games we used in the classroom.

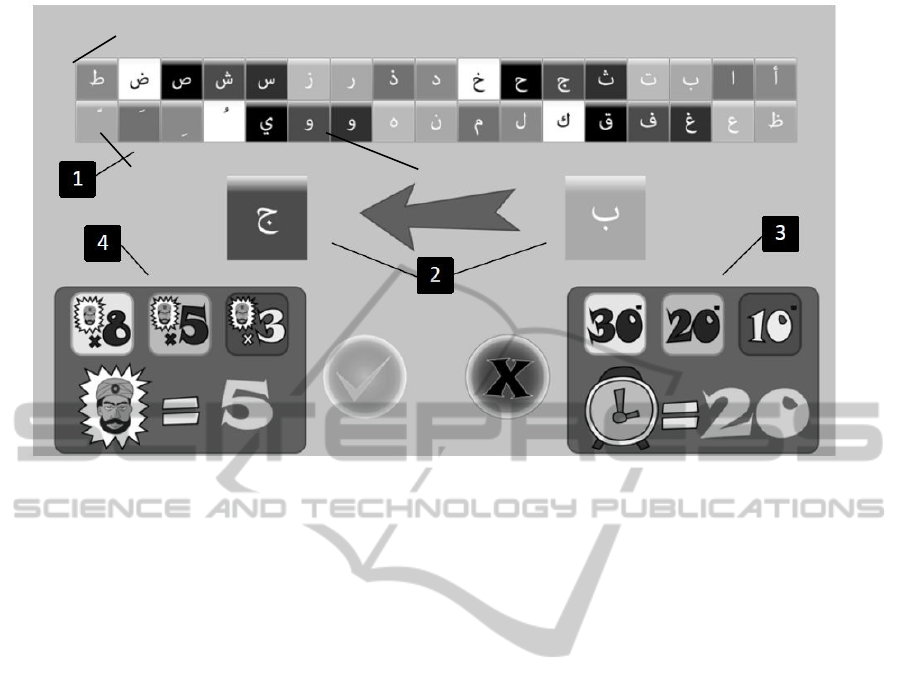

3.3.1 Soundboard

The Soundboard was not a game per se, but we

consider it part of the gaming sessions, since it was

usually preceding the other games. The purpose of

the Soundboard was to mimic the basic function of

the soundboard toy, i.e., teach students how different

objects are pronounced and support them in building

their vocabulary. The interface was compiled by

three main components: (a) the letter bar, showing

34 buttons with all the letters of the Arabic alphabet,

(b) the gallery, containing up to 15 (clip art) images

of objects starting with a specific letter, and (c) the

current item, showing the currently selected image.

Each time a letter was selected, the gallery was

randomly compiled by retrieving images from a

larger pool of images. Spending time in the

Soundboard allowed students to get familiar with the

Figure 1: Soundboard game. 1: Letter bar; 2: Gallery; 3: Current image.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

132

Figure 2: Bingo game start page. 1: Letter bar; 2: Selected range of letters; 3: Seconds per round; 4: Allowed mistakes per

round.

vocabulary and the images they were going to see in

the games to follow.

The idea behind Soundboard is really simple: the

player selects a letter and a gallery of objects that

start with this letter appears. Each time the player

touches an image in the gallery, the system plays an

audio file representing the correct pronunciation of

the word in MSA. The early version of the

Soundboard was designed to accommodate 4 players

per table (i.e., the screen was divided into four equal

parts). However, the number of simultaneous words

played, and the fact that the classroom proved to be

smaller than needed for the number of tables used in

the project created a noise. Because of this, a new

version was developed with only one player per

table (Fig. 1). To make sure that the sound would be

clear for all students to hear, we added an additional

set of speakers. Finally, the activity was eventually

used only on one table operated by the teacher. The

students were surrounding the table, while the

teacher was standing in front of it leading the first

few rounds. After that, the students were taking

turns in touching images and hearing the

pronunciation in MSA.

3.3.2 Bingo

Bingo was the most played game in the study. It was

introduced first to the students and they preferred it

over the other games we introduced later. The idea is

based on the well-known bingo game, modified for

content and instructional goals. Two teams of

students (typically two dyads) per table play against

each other trying to finish first in order to win. In the

beginning of the game, the teacher chooses the range

of letters that are going to appear in the game, along

with the duration of each round and the number of

allowed mistakes per round (Fig. 2).

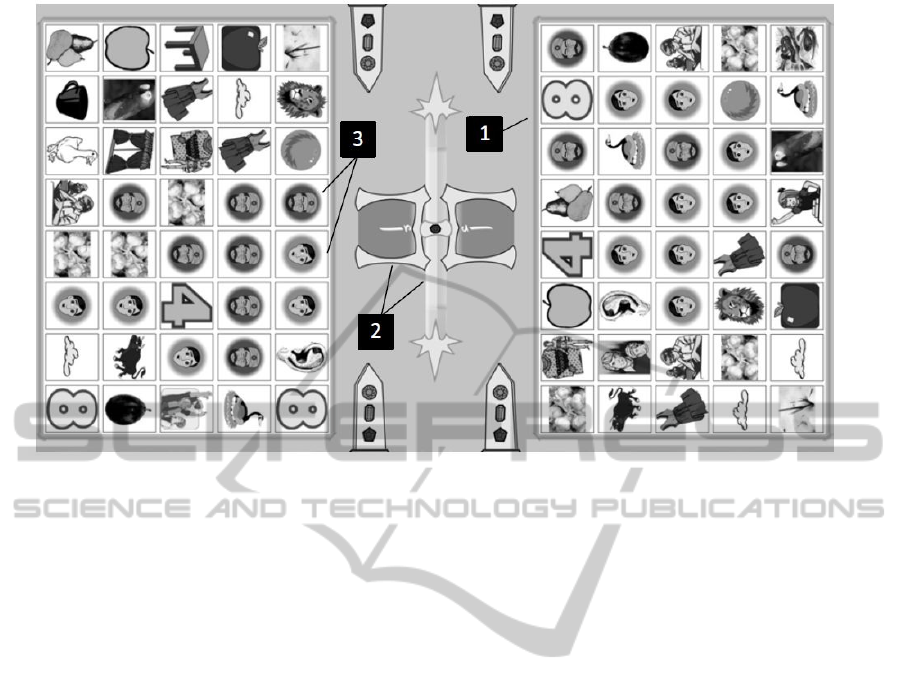

When the game starts, the screen is divided in

half with a gallery of 40 clip art images in each side

(Fig. 3). The system randomly populates the two

galleries, drawing images from the pools of the

selected letters. Each round, the system selects a

letter from the selected range and displays it in the

middle of the screen, along with the remaining time.

The round time and selected letter are common for

the two teams. The students have to touch the

images that start with the round letter. If a touched

image is correct, it is replaced with Aladdin’s face

and remains like that for the rest of the game. In case

of a mistake, the face of the Magician (i.e.,

Aladdin’s nemesis) appears, and the object image

reappears in the next round. A round ends, either

when time runs out, or when both teams reach the

allowed number of mistakes. The game ends, when

one of the teams fills the gallery with Aladdin’s

face.

In terms of pedagogy, the students need to act in

three levels, first identify the objects depicted, then

think (or say out loud) what the pronunciation of the

words in MSA should be, and lastly, decide if the

words start with the same sound represented by the

EducationalGamesforEarlyChildhood-UsingTabletopSurfaceComputersforTeachingtheArabicAlphabet

133

Figure 3: Bingo game. 1: Gallery; 2: Remaining time and round letter; 3: Aladdin’s and Magician’s faces.

letter. Students’ collaboration in teams and the factor

of competition were expected to increase interaction

and engagement.

At the end of each round, the system was

recording the timestamp, the number of total and

correct touches made, and the round letter for each

team in log files.

3.3.3 Get3

This game is a variation of Bingo described above.

The main differences are that Get3 is played

individually, and there is no pressure from time limit

or competitiveness. We designed this game to

complement the data we were expecting from Bingo.

In Bingo, it is not possible to differentiate

between the performances of each player, while the

time limit in each round makes the game harder for

students. Get3, on the other hand, allows the

monitoring of individual performances and gives the

opportunity to weaker or introvert students to take

control of the game and apply their own pace. In

addition making the game an individual one

eliminates competition, and this also lifts some of

the pressure the students might feel while playing.

In term of pedagogy, however, both games

follow the same principle for matching a letter to the

starting sound of word. The combination of these

two games would allow us to better understand

student performance in the study.

In the beginning of the game, the teacher, once

again, selects the letter range, along with the goal

score (i.e., the number of correct responses needed

to end the game). The screen is divided in 4 playing

areas (Fig. 4). Each area has a small gallery of 6

images, a round letter, and indications (number and

bar) showing the score. These four areas function

completely independent from each other. The gallery

has always 3 correct and 3 wrong images and it is

refreshed in each round. In case of a correct touch,

the image is replaced by a diamond, while, in case of

a wrong answer, the image is replaced by an “X”.

After three images are touched, the round ends and

the gallery and the selected letter are refreshed by

the system. This means that in each round, a student

can have 0/3-3/3 success rate. The game ends for a

player (but not for the whole table) when the goal

score of correct answers is reached.

The system monitors students’ activity

individually and records the timestamp, the round

letter, and the success rate for each round. Both

Bingo and Get3 were designed to play sounds on

each touch (pronunciation of the words in MSA).

However, because of the noise issues noted earlier in

Soundboard, the sound was muted.

3.4 Procedure

Students have the Arabic Language class 4 days per

week, at different hours. The class typically lasts 40

minutes, however, because students have to switch

classrooms and since there is not always a break

between classes, the actual duration of the class is

usually 30-35 minutes.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

134

Figure 4: Get3 game. 1: Gallery; 2: Round letter; 3: Total score and score bar.

Gaming sessions were usually taking the last part of

the class (~10’), although, there were also sessions

covering the whole class. Students played some of

the games a few times per week. The class was

controlled by the school teacher, with the principal

investigator of the project also in the classroom to

observe and take notes. The students were

distributed to the 5 available tables in the classroom

by the teacher. Although organizing students into

groups of 3-4 students per table was mostly done

randomly, factors such as gender, interpersonal

relationships, and general student performance were

often taken into account by the teacher, in order to

have a balanced distribution. Group formation and

students’ spots were changing in each class, and,

while it was not encouraged, students changing spots

during a class was not forbidden either. It is

important to note that students’ identities were not

part of the data collected by the tables or the

researchers of the study.

While the number of allowed mistakes (5) and

the duration of each round (20’’) remained the same

for most Bingo games played, the number of letters

selected varied significantly to accommodate

instructional needs. A higher number of letters

means that, respectively, a lower number of images

will appear for each letter in the gallery in the

beginning of the game. This makes the game more

difficult as students have fewer chances to find a

correct image. On the other hand, as students

proceed successfully, finding correct images and

getting the number of remaining available images in

the gallery (i.e., not covered by Aladdin’s face)

much lower, the game gets easier (up to the last

round, where the only available image is also a

correct one).

In contrast, the number of selected letters did not

affect the difficulty level in the Get3, since the

number of correct images in the gallery in each

round remained constant (3 out of 6).

4 RESULTS

Analysis is based on descriptive statistics, while

deeper analysis will be necessary to assess students’

behavior through the thousands of touches recorded

in the study.

Using the tabletop surface computers was easy

for the students. Familiarization phase game was

also short, since students were soon able to use the

system on their own.

Table I shows the results from the Bingo log

files, for each of the 12 total days the game was

played. Students’ performance varied significantly

according to (a) the number of selected letters, (b)

the number of letters that were new and had not been

played before, and (c) their familiarization with the

images of each letter through other games. In

addition, there were in-game factors that could affect

the success percentage. For example, in the

beginning of a game a letter might correspond to 10

correct images in the 40-image gallery, thus giving

EducationalGamesforEarlyChildhood-UsingTabletopSurfaceComputersforTeachingtheArabicAlphabet

135

Table 1: Bingo success percentages/per letter/per day.

Day Alif \w h Alif Baa Ta Thaa Jiim Ha Khaa Daal Dhaal Raa Zaay Total

8/10 49.59 41.73 49.54 46.95

23/10 36.90 45.92 43.49 40.63 41.73

30/10 37.86 32.08 32.90 40.83 38.12 36.36

5/11 40.62 31.44 31.04 36.97 35.28 43.58 36.49

6/11 65.91 64.54 65.22

11/11 46.63 43.57 40.57 43.59

13/11 46.39 48.05 50.58 48.96 48.50

18/11 42.49 43.24 46.95 44.69 44.34

25/11 48.45 51.25 50.71 51.41 50.46

2/12 30.23 30.25 48.65 36.08 36.21 47.46 50.16 41.83 32.36 43.91 45.53 47.98 40.89

3/12 42.33 24.74 52.18 42.58 27.74 55.02 69.69 40.56 33.03 21.53 29.45 33.75 39.38

4/12 28.31 32.20 43.92 42.90 31.62 40.53 43.92 27.43 35.66 37.74 56.96 51.39 39.38

Avg. % 37.98 34.05 43.10 40.00 39.15 49.16 49.65 41.81 41.37 39.72 45.84 44.37 42.18

Touches 984 1001 831 754 1156 1547 928 1356 1138 786 495 156 11132

Images 362 341 327 269 580 771 391 582 491 334 224 56 4728

students a 25% chance of success. In this case the

selection of a correct image by the students might

indicate that the students were indeed aware of the

correct answer. As the game progresses, both the

number of available correct images and the number

of remaining available images in the gallery change

randomly (e.g., the sequence in which the system

selects the letters and the number of correct

responses from the students in each round cannot be

predicted). As such, the values presented in Table I

cannot be analyzed as absolute values (in which case

a 40% success rate would mean a mediocre

performance), but only by comparing them to each

other.

One characteristic example of how the number of

selected letters affected students’ performance is

provided on the statistics on 6/11 (marked grey in

the table). When we decided to use only two letters

in the gallery, students’ scores peaked, exceeding

65% - much more than the total average (42%).

Regarding familiarization with the images, it seems

that students had trouble differentiate between the

letters “Alif with hamza” and “Alif”, making more

mistakes when “Alif” was selected.

Get3 was played sporadically a little after we

introduced Bingo. In the beginning, not all students

wanted to switch from Bingo to Get3, because they

enjoyed more the collaborative nature of the first

one. We asked the teacher to organize a few gaming

sessions during the last week of the study, having all

students playing the game. During these sessions, we

gathered data for the first 8 letters (Fig. 5).

When reading the statistics, one has to have in

mind the expected percentage in each occasion. As

we mentioned earlier, several factors affect students’

performance. Therefore, numbers in the two games

should not be directly compared, but correlated.

Results showed that students were able to recognize

all the letters adequately, scoring once again lower

in the letter “Alif” and corroborating the finding we

had from analyzing Bingo data.

One more important note regarding the results is

that the games used a pool of 600+ clip art images,

and these images appeared thousands of times over

the course of 9 weeks (e.g., 4728 just in Bingo). This

extensive exposure to images and words is very

important, especially if we take into account that

students considered learning through these games as

a reward for successfully completing other tasks,

such us writing and discussion.

Figure 5: Students’ success percentage in Get3 game.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

136

Regarding students’ attitudes towards the new

curriculum, the positive feedback we received was

evident in many forms. For example, many students

asked us to develop versions of the games for their

tablet computers, “so that they could play at home”

as they stated. The students were rushing to the

“Arabic Studies” classroom, contrary to what

typically happens for other classes, where students

are escorted to a classroom following behind a

teacher in a single-file line. Parents, teachers, and

students of other classes (both from kindergarten and

the co-located primary school) expressed a vivid

interest in participating in similar activities, while

the activities of the project recently attracted

attention from Media in the region (e.g., Gulf News,

2014; Gulf Times, 2014).

On the down side, some of the images used in

the games were causing confusion to the students

regarding the words they were depicting. The use of

sound would be enough to clear this issue for the

students, however, as we mentioned earlier, sounds

had to be muted to avoid noise in the classroom.

Finally, the number of the students in the study was

easily accommodated by the number of available

tables. In case of a larger group, more tables would

be necessary to keep every student active. After

observing students’ activity during 9 weeks, be

believe that it would be challenging for the teacher

to manage a class in which some of the students

need to wait for their turn in the tables.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The papers presented the initial analysis of the data

gathered in the gaming activities of the ALADDIN

project. Acceptance and engagement was very high

and there are strong indications for the effectiveness

of the approach. However, improvements are also in

order. First and foremost, due to the size of the

classroom and the characteristics of the tables, most

of the activities were lacking audio feedback. A

larger space would allow us to have a better control

of the sound. Second, the pool of images (and the

words they depict) needs to be revised and

expanded. Results showed that the students saw each

image numerous times. Using more images would

make the games even more interesting and would

enhance students’ vocabulary.

Indeed, we are already in process of developing

additional games, expanding our initial learning

goals and including games recognition and

production of word and small sentences. In the

meantime, modifications and improvements are also

under way for the games we presented here.

Finally, it is already in our intentions to develop

tablet versions of the activities. It would be

interesting to see whether this approach would

increase students’ engagement with the material and

whether the lack of a shared interface would affect

students’ performance and attitudes. However, it is

certain that the tablet versions would allow for

project deliverables to be better disseminated into

society.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been funded by a grant from QNRF

(Qatar National Research Fund), NPRP Project 4-

1074-5-164 titled “Advancing Arabic Language

Learning in Qatar”.

The authors would like to thank Christos-

Panagiotis Papazoglou and Sachin Mousli for their

contribution in the development of the games

presented here. They also thank Jamila Al-

Shammari, the class teacher; Hanan Mohamed for

developing further the games, including new ones

for future studies; Zahra Moufid for helping in

gathering the content (images and words) used, and

Sara Shaaban for the designing the images related to

the Aladdin folklore story.

REFERENCES

Behnstedt, P. (2006). Dialect Geography. In Encyclopedia

of Arabic Language and Linguistics (Vol. 1, pp.

583-593). Leiden: Brill.

Ferguson, C., 1991. Epilogue: Diglossia Revisited.

Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 10(1), 214.

Gulf News (2014, January 23). Qatar uses interactive tool

to teach Standard Arabic. Gulf News. Retrieved

January 23, 2014, from http://gulfnews.com/news/

gulf/qatar/qatar-uses-interactive-tool-to-teach-

standard-arabic-1.1281158.

Gulf Times (2014, January 26). CMUQ Team Develops

New Method to Teach Arabic. Gulf Times, p. 10.

Retrieved January 26, 2014, from http://www.gulf-

times.com/Mobile/Qatar/178/details/379019/CMUQ-

team-develops-new-method-to-teach-Arabic.

Hainey, T., Connolly, T.M., Stansfield, M., and Boyle,

E.A., 2011. Evaluation of a game to teach

requirements collection and analysis in software

engineering at tertiary education level. Comput. Educ.,

56(1), 21-35.

Ibrahim, Z., 2000. Myths About Arabic Revisited. Al-

Arabiyya, 33, 13-27.

EducationalGamesforEarlyChildhood-UsingTabletopSurfaceComputersforTeachingtheArabicAlphabet

137

Ibrahim, Z., 2008. Lexical Separation: A Consequence of

Diglossia. Cambridge University Symposium,

Cambridge.

Ibrahim, Z., 2009. Beyond Lexical Variation in Modern

Standard Arabic. London: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing.

Ibrahim, Z., 2013. Love – Fear Relationship: Arab

Attitudes toward the Arabic Language. In The

Eminent Scholars Series: Interculturalism. Essays in

honor of Professor Mohamed Enani. 339-360.

Kebritchi, M., and Hirumi, A., 2008. Examining the

pedagogical foundations of modern educational

computer games. Comput. Educ., 51(4), 1729-1743.

Kerne, A., Koh, E., Dworaczyk, B., Choi, H., Smith, S.,

Hill, and R., Albea, J., 2006. Supporting Creative

Learning Experience with Compositions of Image and

Text Surrogates. In Proc. World Conference on

Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and

Telecommunications. Chesapeake, VA: AACE, 2567-

2574.

Meluso, A., Zheng, M., Spires, H.A., and Lester, J., 2012.

Enhancing 5th graders' science content knowledge and

self-efficacy through game-based learning. Comput.

Educ., 59(2), 497-504.

Morris, M.R., Piper, A.M., Cassanego, T., and Winograd,

T., 2005. Supporting Cooperative Language Learning:

Issues in Interface Design for an Interactive Table.

Stanford University. Technical Report.

Papadopoulos, P. M., Ibrahim, Z., & Karatsolis, A. (2014).

Teaching the Arabic Alphabet to Kindergarteners -

Writing Activities on Paper and Surface Computers. In

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education – CSEDU 2014,

Barcelona, Spain. DOI: 10.5220/0004942204330439.

Papastergiou, M., 2009. Digital Game-Based Learning in

high school Computer Science education: Impact on

educational effectiveness and student motivation.

Comput. Educ., 52(1), 1-12.

Piper, A.M. (2008). Cognitive and Pedagogical Benefits of

Multimodal Tabletop Displays. Position paper

presented at the Workshop on Shared Interfaces for

Learning.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., 2007. Linguistic constraints on

children's ability to isolate phonemes in Arabic.

Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 605-625.

Vangsnes, V., Økland, N.T.G., and Krumsvik, R., 2012.

Computer games in pre-school settings: Didactical

challenges when commercial educational computer

games are implemented in kindergartens. Comput.

Educ., 58(4), 1138-1148.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

138