The Impact of Ranking Information on Students’ Behavior and

Performance in Peer Review Settings

Pantelis M. Papadopoulos

1

, Thomas D. Lagkas

2

and Stavros N. Demetriadis

3

1

Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

2

The University of Sheffield, City College, Thessaloniki, Greece

3

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Keywords: Peer Review, Free-Selection, Gamification, Computer Science Education, Motivation.

Abstract: The paper explores the potential of usage and ranking information in increasing student engagement in a

double-blinded peer review setting, where students are allowed to select freely which/how many peer works

to review. The study employed 56 volunteering sophomore students majoring in Informatics and

Telecommunications Engineering. We performed a controlled experiment, grouping students into 3 study

conditions: control, usage data, usage and ranking data. Students in the control condition did not receive

additional information. Students in the next two conditions were able to see their usage data (logins, peer

work viewed/reviewed, etc.), while students in the last group could additionally see their ranking in their

group according to their usage data. Results showed that while the three groups were comparable, a range of

different attitudes were visible in the Ranking group. Students with more positive attitude towards ranking

were more engaged and outperformed their fellow students in their group.

1 INTRODUCTION

This study explores the potential of ranking

information, as a type of gamification approach, in

enhancing student engagement and performance in a

peer review setting. Peer review is a popular

instructional approach with a plethora of applied

approaches found in the literature, able to support

both the acquisition of domain knowledge and the

development of higher level skills related to

reviewing. Although studies on peer review are

primarily focused on higher-level learning skills

such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation

(Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), there are also

reported benefits on lower level learning (e.g.,

introductory knowledge) (e.g., Turner, Pérez-

Quiñones, Edwards, & Chase, 2010). Peer review

engages students in a constructive and collaborative

learning activity (McConnell, 2001) stimulating and

guiding higher cognitive processes of learning

(Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1994). This is why the

method has been used extensively in various fields

such as second language writing (Hansen & Liu,

2005; Lundstrom & Baker, 2009), statistics (Goldin

& Ashley, 2011), and computer science (Liou &

Peng, 2009; Luxton-Reilly, 2009), our domain in

this study.

Researchers refer to the roles students play in

peer review as “assessors vs. assessees” (Li, Liu, &

Steckelberg, 2010) or “givers vs. receivers”

(Lundstrom and Baker, 2009) and report different

learning outcomes identified for these two different

peer roles. For example, Li et al. (ibid.) report that

the quality of students’ final projects exhibited a

significant relationship to the quality of peer

feedback they provided, while no such relationship

was identified for students receiving feedback.

Similarly, Lundstrom and Baker (ibid.) conclude

that students who reviewed their peers’ writings

were significantly benefited in their own writing,

outperforming those students who only received

peer feedback.

Our interest in the peer review method is focused

on settings where students are to select freely which

peer work to review, without an instructor, a system,

or a method assigning specific work to them. We

refer to this instantiation of the peer review method

as Free-Selection review protocol and it will be the

backdrop of our current study. We have explored the

potential of Free-Selection in previous studies

(Papadopoulos, Lagkas, & Demetriadis, 2012;

2015), showing that when students are allowed to

139

M. Papadopoulos P., D. Lagkas T. and N. Demetriadis S..

The Impact of Ranking Information on Students’ Behavior and Performance in Peer Review Settings.

DOI: 10.5220/0005472801390147

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 139-147

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

select which peer work to review, they tend to

provide feedback to more fellow students than the

required minimum and they read several peer works

before they make their selection. Thus, they are

exposed to a greater range of different perspectives.

Eventually, students in the Free-Selection condition

are able to acquire higher level of domain

knowledge and improve their reviewing skills more

than students that were randomly assigned peer

work. Other studies have also reported significant

benefits from allowing students to select freely

which peer work to review. Online systems such as

PeerWise (http://peerwise.cs.auckland.ac.nz/) and

curriculearn (http://curriculearn.dk/src/index.php),

both focusing on student-generated questions,

support peer review methods without limiting the

number of reviews a student can perform. In such

systems, students with higher grades tend to

contribute more than weaker students, thus resulting

in a greater amount of higher quality feedback being

produced (Luxton-Reilly, 2009).

However, in Free-Selection settings, the success

of the learning activity is heavily based on the level

of student engagement. One of the approaches often

used to keep students’ engagement high is

gamification. Deterding et al. (2011) define

gamification as the use of game design elements in

non-game contexts. Such elements could be winning

points, leaderboards, achievements and badges, and

ranking systems. Denny (2013), for example, reports

a highly significant positive effect on the quantity of

students’ contributions and the time they spent in

PeerWise, in an activity were a large number of

students (n>1000) were awarded virtual

achievement/badges for different levels of

participation in the PeerWise system (e.g., volume

of work submitted, volume of peer feedback

submitted, etc.).

In our context, an approach based on badges

would not be appropriate, since the population of the

students (usually 50-60) and the duration of a typical

online activity in a course (2-3 weeks) are not

enough to allow a high volume of peer work and

feedback to be produced. We decided to focus in this

study on ways to enhance students’ engagement in

peer review, by providing usage and ranking

information. Usage information refers to the effort

put by the students in the activity, as evident by the

number of logins in the learning environment used,

the number of peer submissions read, and the

number of reviews submitted. Ranking information

provides additional value to these data, by also

informing students on their relative position in the

group for each of the usage metrics. The study

examined whether this additional information would

trigger additional motives to the students, or whether

ranking information could have a detrimental effect

on students’ behavior.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

The course “Network Planning and Design” is a core

course, offered in the fourth semester of the 5-year

study program “Informatics and

Telecommunications Engineering” in a typical

Greek Engineering School. The course focuses on

analyzing clients’ needs, identifying system

specifications, and designing appropriate computer

networks. As such, it targets students with a strong

technical profile. The study employed 56 students

that volunteered to participate in the activity and

receive a bonus grade for the lab part of the course.

We randomly assigned the students into three study

conditions:

Control: 18 students (11 male, 7 female);

Usage: 20 students (11 male, 9 female);

Ranking: 18 students (10 male, 8 female).

Although the activity tasks were identical for all

students, the information presented to them differed.

Students in the Control group did not receive any

additional information on their activity, students in

Usage group received information on their personal

progress, while students in the Ranking group

received, additionally to the information of personal

progress, their current rankings in their groups.

2.2 Domain of Instruction

The domain of instruction was “Network Planning

and Design”, which is a typical ill-structured domain

characterized by complexity and irregularity. The

outcome of a NP&D technical process results from

analyzing user requirements and demands

compromise in balancing technology against

financial limitations (Norris & Pretty, 2000). The

network designer has to solve an ill-defined problem

set by the client. The role of the designer is to

analyze the requirements, which are usually not fully

specified, and follow a loosely described procedure

to develop a practical solution. Computer network

design involves topological design and network

synthesis, which are best conceived through

studying realistic situations. Students in Computer

Engineering learn to face realistic complex problems

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

140

and they can be greatly benefited by project-based

learning methods (Martinez-Mones et al., 2005).

2.3 Material

2.3.1 The Learning Environment

The learning environment eCASE was originally

designed as a generic platform, able to support

individual and collaborative learning in ill-structured

domains. The benefit of using a custom-made tool is

that we are able to tailor and modify the study

conditions to address our current research needs. For

example, different versions of the system have been

used in previous studies on scaffolding in case-based

learning (Demetriadis, Papadopoulos, Stamelos, &

Fischer, 2008), on students’ collaboration patterns in

CSCL (Papadopoulos, Demetriadis, & Stamelos,

2009), and on peer review settings (Papadopoulos,

Lagkas, & Demetriadis, 2012).

The system applies case-based instruction and

the material is organized into two categories, the

realistic open-ended scenarios that present the

problem context, and the past cases, providing

supporting material that allows students to address

the issues presented in the scenarios. The scenarios

referred to various installations of computer network

systems in new/restructured facilities. A number of

past cases were accompanying each scenario,

presenting similar past projects and highlighting

important domain factors, such as the cost of the

project, efficiency requirements, expansion

requirements, and the traffic type and end-users’

profile. Students in the study had to take into

account the specific conditions and the contexts

presented, and propose their own computer networks

as answers to the 3 available scenarios.

Regarding the review procedure and the

usage/ranking information presented to students, the

system carried the weight of collecting all

deliverables, granting students access to peer work,

and monitoring student activity throughout the study

phases. While having our own system allows us for

better control of the study, the system itself is not

part of the analysis.

2.3.2 Pre-Test and Post-Test

Students took two written tests. The pre-test

instrument had 6 open-ended questions on domain

knowledge (e.g., “How does knowledge on the end-

user profile of a network affect its architecture?”).

The purpose of the pre-test was to record students’

prior knowledge on the domain and provide a

reference point to our analysis. Similarly, the post-

test also focused on domain knowledge, including 3

open-ended questions (e.g., “What kind of changes

may occur in the architecture of a network, when the

expansion requirements are increased?”). The post-

test focused on the domain knowledge students

acquired through the study.

2.3.3 Attitude Questionnaire

At the end of the study, we asked students to fill out

an online questionnaire recording their opinions and

comments on different aspects of the activity, such

as: the identity of their reviewers, the effect of

usage/ranking data on their performance, the

helpfulness of peer comments, and the amount of

time they spend in each phase in the learning

environment. Students were able to address these

questions through a combination of open and closed-

type items.

2.4 Design

The study followed a pre-test post-test experimental

research design to compare the performance of the

three groups. The presentation of usage and ranking

information was the independent variable. Students’

performance in the environment, in the written tests,

and in their answers in the attitudes questionnaire

were the dependent variables. The study had 6

distinct phases: Pre-test, Study, Review, Revise,

Post-test, and Questionnaire.

2.5 Procedure

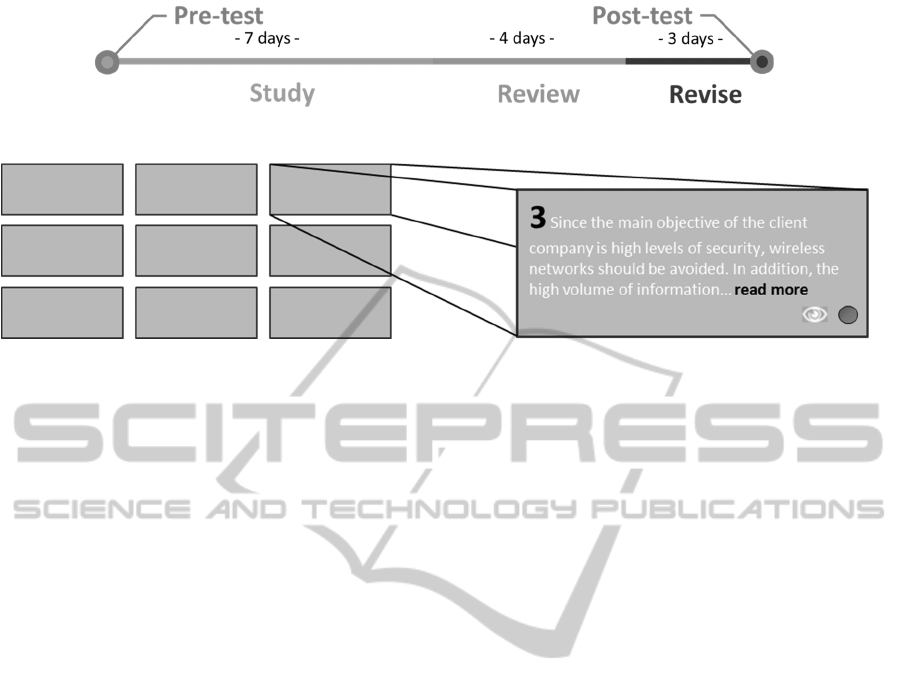

Figure 1 shows the sequence and the duration of

each phase. The study lasted 2 weeks, starting with

the written pre-test in the class. Right after, the

students gained access to the online learning

environment and started working (from wherever

and whenever they wanted) on the 3 scenarios and

the accompanying past cases. We allowed students 1

week to read all the material and submit their

descriptions of the 3 computer networks they

suggested. These are considered as “students’ initial

answers” to the scenarios.

At the end of the first week, students continued

with the Review phase that lasted 4 days. During

this period, the system allowed to students access to

all peer work (that is, peers’ initial answers) in the

same group. The peer review process was double-

blinded, and students were free to read and review as

many peer works they wanted, with a minimum

requirement of 1 review per scenario. The first few

TheImpactofRankingInformationonStudents'BehaviorandPerformanceinPeerReviewSettings

141

Figure 1: Activity phases.

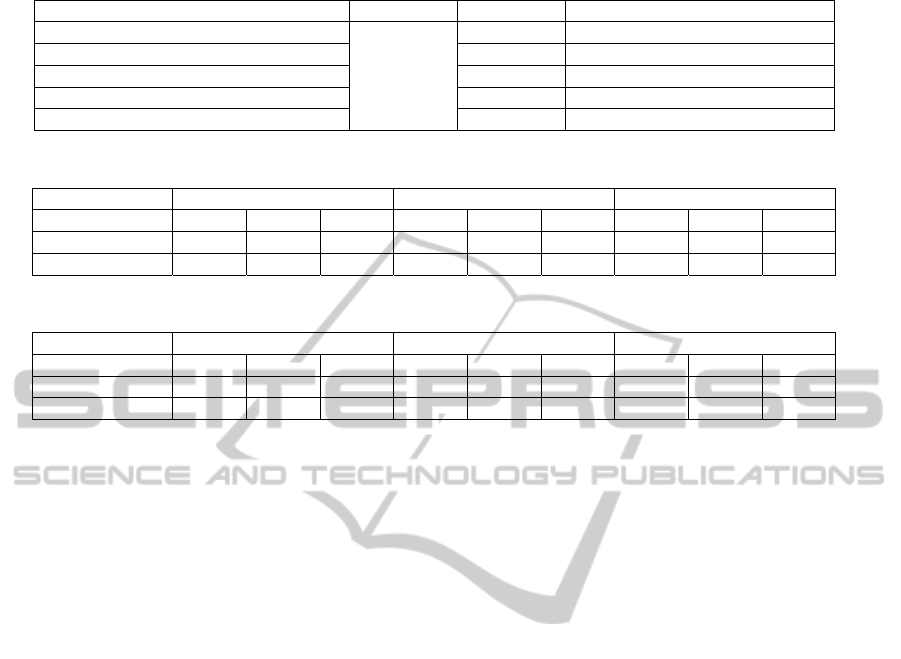

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the answer grid. In this depiction, peer answer no.3 has been read and reviewed by

the user.

words (~150 characters) of all students’ initial

answers were presented in random order in a grid

formation along with icons showing whether an

answer has already been read (eye) and reviewed

(green bullet) by the user (Fig. 2).

Each time a student clicked on the “read more”

link of an answer, the system recorded the event and

presented the whole answer along with a review

form including guidelines and asking students to

analyze: (a) the basic points of the peer work, (b) the

quality of the provided argumentation, and (c) the

eloquence and clarity of the work.

Along with the comments, the reviewer had to

also suggest a grade according to the following 5-

step Likert scale: “1: Rejected/Wrong answer; 2:

Major revisions needed; 3: Minor revisions needed;

4: Acceptable answer; 5: Very good answer”.

As we mentioned earlier, the study tasks were

identical for all students in the three groups.

However, what differed was the additional

information they had available during the Review

and Revise phases. The selection of a usage metric

could imply to the students that this metric is related

to better outcomes. Since our objective was to

enhance engagement, we selected metrics that would

suggest to students to: (a) visit the learning

environment more often, (b) get more points of view

by reading what others said, and (c) provide more

feedback to peers. As such, during the Review

phase, students in the Usage and Ranking group

were able to see live results on:

The number of times they logged into the

learning environment;

The total number of peer work they have read;

The total number of peers work they have

reviewed.

It is important to underline that these 3 metrics did

not provide any additional information to the

students, since a meticulous student could keep track

of her activity during the study (of course, we did

not ask students to do so, nor we were expecting

them to do so). In addition to these metrics, students

in the Ranking group were also provided with

information by the system regarding their rankings

and their group’s mean values. This information was

something that students could not have calculated

themselves. In addition, chromatic code was used to

denote the quartile according to the ranking (1st:

green; 2nd: yellow; 3rd: orange; 4th: red).

After the Review phase was completed, no

further reviews were possible and the review

comments became available to the respective

authors. Students had 3 days in the Revise phase to

read the comments they received and revise their

initial work on the three networks as they considered

fit. Students that did not receive peer comment on a

submitted work had to fill out a self-review form

before they were allowed by the system to edit their

initial answer. The self-review form provided

students with guidance on how to analyze and

compare their work with that of others by: (a) listing

the components of their own network, (b) provide

appropriate argumentation for each component, (c)

grade themselves, and (d) identify and explain

intended revisions.

In order for the system to consider this phase

completed, all students had to submit a final version

of their answers for each scenario, even if no

revisions were made. In the beginning of the

Revision phase, one more metric was available to

the Usage and Ranking groups, the average scores

received from peers, along with the number of

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

142

Table 1: Example of what usage/ranking information students in each group were seeing.

Control Usage Ranking

metric

value value mean ranking

Number of logins in the environment 12 15 9.4 4th

Peer work viewed in total <no data> 9 6 13.9 17th

Peer work reviewed in total 5 5 4.5 6th

Score received from peers (no of peers) 3.8 (5) 3.1 (4) 3.4 11th

Table 2: Pre-test and post-test performance.

Control Usage Ranking

(scale: 0-10)

M SD n M SD n M SD n

Pre-test

2.11 (0.98) 18 1.98 (1.01) 20 2.02 (1.09) 18

Post-test

8.17 (1.01) 18 8.10 (0.96) 20 8.11 (0.93) 18

Table 3: Learning environment performance.

Control Usage Ranking

(scale: 1-5)

M SD n M SD n M SD n

Initial

2.94 (0.58) 18 3.12 (0.75) 20 2.80 (0.77) 18

Revised

3.44 (0.67) 18 3.64 (0.58) 20 3.49 (0.77) 18

received reviews. This was the one metric that

students could not affect. Table 1 presents an

example of the type of information students in the

three groups were seeing.

After the Review and Revise phases, the students

took a written post-test in class, followed by the

attitudes questionnaire that concluded the activity.

3 RESULTS

To avoid biases, students’ answer sheets of the pre

and post-test were mixed and blindly assessed by

two raters that followed predefined grading

instructions. For all statistical analyses a level of

significance at .05 was chosen. To validate the use

of the parametric tests, we investigated the

respective test assumptions and results showed that

none of the assumptions were violated. We

calculated the two-way random average measures

(absolute agreement) intraclass correlation

coefficient (ICC) for the raters’ scores, as a measure

of inter-rater reliability. Results showed high levels

of agreement in each variable (>0.8).

3.1 Written Tests

Table 2 presents students’ scores in pre and post-

test. Students were novices in the domain, scoring

very low in the pre-test instrument. In addition,

analysis of variance (ANOVA) results showed that

the three groups were comparable in pre-test

(p>.05), suggesting that the random distribution of

students in the three conditions we performed was

valid. To compare the outcomes in the three groups,

we performed one-way analysis of covariate, using

pre-test score as the covariate. Results, once again,

showed no statistical differences between the three

groups (p>.05).

3.2 Learning Environment

Table 3 presents students’ scores during the two

weeks of the activity in the learning environment

(Study, Review, and Revise phases). Scores

represent the average scores students received in the

3 scenarios. Raters used the same 1-5 scale as the

students did during the Review phase (1:

Rejected/Wrong answer; 2: Major revisions needed;

3: Minor revisions needed; 4: Acceptable answer; 5:

Very good answer).

One-way ANOVA results for the two variables

revealed no statistically significant differences

between the three groups (p>.05). This was expected

for the scores of Study phase, since the study

conditions were identical for all students. The lack

of statistical difference in the scores of the second

week, though, suggests that the use of usage/ranking

information did not provide a significant benefit to

the Usage and Ranking groups, although paired-

samples t-test results showed significant

improvement between the scores of the initial and

the revised submissions (p<.05) for all groups.

Finally, Table 4 presents students’ data on the four

usage metrics. Once again, result analysis showed

that the three groups were comparable.

TheImpactofRankingInformationonStudents'BehaviorandPerformanceinPeerReviewSettings

143

Table 4: Usage metrics performance.

Control Usage Ranking

M SD n M SD n M SD n

Logins

30.29 (12.90) 18 28.73 (14.02) 20 28.06 (14.44) 18

Views

12.54 (9.26) 18 11.47 (10.57) 20 14.31 (7.69) 18

Reviews

4.31 (1.02) 18 4.18 (1.21) 20 4.21 (0.93) 18

Peer Score

3.61 (0.89) 18 3.56 (0.91) 20 3.51 (1.10) 18

Table 5: Questionnaire responses.

Control Usage Ranking

(n=18) (n=20) (n=18)

M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)

Q1. Would you like to know the identity of your peers

that reviewed your answers? (1: No; 5:Yes)

1.70 (0.80) 1.95 (1.16) 1.84 (1.30)

Q2. How many hours did you spend approximately in

the activity during the first week (Study phase)? (in

hours)

10.08 (3.09) 10.12 (3.80) 9.59 (3.94)

Q3. How many hours did you spend approximately in

the activity during the second week (Review and Revise

phases)? (in hours)

2.48 (1.40) 2.33 (1.01) 3.31 (1.13)*

Q4. Would you characterize the usage information

presented during the second week as useful or useless?

(1: Useless; 5: Useful)

n.a. 4.33 (1.06) 4.26 (0.81)

Q5. Would you characterize the ranking information

presented during the second week as useful or useless?

(1: Useless; 5: Useful)

n.a. n.a. 3.53 (1.07)

3.3 Questionnaire

Table 5 presents students’ responses in the most

important items of the attitudes questionnaire.

Additionally, the students had to answer in open-

ended questions giving more details on the 5 items

mentioned in Table 5. Students did not express an

interest in knowing who submitted the reviews they

received (Q1). Out of the 56 students in the study,

only 4 asked to know the identity of the reviewers,

either because they were curious (n=3), or because

they had strong opinions against the reviews they

received (n=1).

We had asked the students to keep track of time

throughout the activity and report this time in the

questionnaire. We had already calculated an

estimation of time spent in the environment.

However, this estimation could have been skewed,

since there was no way to know whether an open

browser window meant that the student was actually

studying. We decided to keep the log data as

reference and compare them to the time students

self-reported. According to students’ responses, the

3 groups were comparable (p>.05) on the time spent

during the first week (Q2). On the contrary, students

in the Ranking group spent significantly more time

(F(2,53)=3.66, p=.03) in the learning environment

during the second week (Q3). The big drop between

the first and the second week was expected. During

the first week, students have to read a lot of material

and answer the scenario questions. On the contrary,

during the second week, students’ workload is

significantly lower, since peers’ answers are shorter,

while revising a scenario answer also takes less time

than writing an initial one.

Regarding the usefulness of the usage data

presented during the second week, almost all

students in Usage and Ranking groups had a positive

opinion, with only 3 students saying that they did

not pay attention to these and did not consider them

important for the activity (Q4). However, when

asked in an open-ended item of the questionnaire to

elaborate on the ways that this information helped

them, students stated that having these data was

rather “nice” and “interesting” than “useful”. The

consensus was being aware of usage data did not in

any way affect how they studied or understood the

material.

Students’ opinions were split, however, when

asked about the ranking information. The majority

of students (n=10) in the Ranking group had a

positive opinion (4:Rather Useful; 5:Useful), while 4

students said that this information was rather useless

(Q5). Students that had a positive opinion found

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

144

Table 6: Ranking sub-groups performance.

Logins* Views* Reviews Peer Score* Post-Test*

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD

Indifferent (n=8)

21.88 (5.17) 10.50 (6.58) 4.00 (1.00) 2.89 (0.93) 7.53 (0.78)

InFavor (n=10)

33.78 (4.43) 18.22 (7.46) 4.45 (1.13) 3.83 (0.67) 8.59 (1.02)

ranking information more interesting and useful,

because, according to them, they could use this

information and improve their performance. For

example, a student in the top quartile said: “I liked

knowing my ranking in the group and it was

reassuring knowing that my peers graded my

answers that high.”

3.4 The Ranking Group

The different attitudes recorded by Q4 and students’

statements raised the need to further analyze

students’ performance and behavior in the Ranking

group. We divided the group into two subgroups: (a)

InFavor, including the 10 students with positive

opinions towards ranking (Q4), and (b) Indifferent,

including the rest 8 students that where either neutral

or negative against ranking. Table 6 presents the

subgroups’ performance in the learning environment

and the written post-test.

T-test result analysis showed that there was a

significant difference between the two subgroups in

the number of logins (t[16]=5.26, p=.00), the

number of peer work read (t[16]=2.29, p=.03), the

score they received from peers on the initial answers

(t[16]=2.49, p=.02), and the scores in the written

post-test (t[16]=2.42, p=.02). However, no

significant difference was recorded for the number

of reviews students submitted (p>.05). Since ranking

is based on the actual value of a metric, students in

the InFavor subgroup were usually on the top 10

positions in the Ranking group.

4 DISCUSSION

As we mentioned earlier, the selection of usage

metrics requires additional attention, because it

underlines to the students the aspects of the activity

that should be enhanced. The badges, reputation

scores, achievements, and rankings employed in

various cases are all aiming to enhance student

engagement and performance (e.g., submit this much

work/answer correctly this many questions in a

row/etc. to receive this badge). However, receiving a

badge or a high ranking position among their peers

does not change the study conditions for the

students. In that sense, achieving a higher

participation level in a learning activity is different

than doing the same in a company’s loyalty program

where, for example, reaching a higher level (e.g.,

becoming gold member of an airline company)

means receiving more benefits (e.g., additional

check-in luggage). Despite this, presenting students

with ranking information, badges, or reputation

points may still increase their intrinsic motivation

and result in deeper engagement. Of course, students

filter the learning activity and adapt it according to

their own goals and strategies, meaning that the

reaction towards ranking could vary.

This became apparent in the Ranking group of

the study. Students that explicitly stated an interest

for their rankings in their group were more active in

the learning environment and achieved higher scores

in the post-test. One interesting finding is that these

students also received significantly higher scores

from their peers in their initial answers in the

eCASE. Since, the initial answers were submitted

earlier during the Study phase, where no

usage/ranking information was available yet, we

could hypothesize that these students were also the

ones that had achieved higher levels of knowledge

or felt more comfortable in the learning activity. A

certain limitation of the study is that the comparison

of the InFavor and Indifferent subgroups is based on

a small population. Although statistical analysis

revealed significant differences in almost all the

study variables, we report these findings with

caution, suggesting that a study with larger

population could provide a better picture.

Contrary to the ranking information, usage data

were broadly accepted with a positive attitude from

students in the Usage and Ranking groups. However,

providing usage data alone was not enough for these

groups to outperform the Control group. Providing

only the values of the usage metrics without a

reference point related to the group was perceived as

“nice” but not enough to trigger different behaviors

of better performance. It was impossible for a

student to self-regulate and self-organize her activity

knowing only her personal usage data. This kind of

information could be useful in a longer activity

where the students would be able to monitor their

activity throughout different periods of time. In that

way, the reference point would be, for example, the

activity patterns of previous weeks.

TheImpactofRankingInformationonStudents'BehaviorandPerformanceinPeerReviewSettings

145

In performing a case-by-case analysis to get a

better picture on how rankings could have affected

students, we also identified cases that could be

problematic. Of course, even in the same sub-

groups, we found a range of different behaviors. For

example, there were students who discarded the

ranking information completely, students who tried

only in the beginning to keep up with the others, and

students who pursued a higher ranking until the end

of the activity. Introducing ranking information into

a learning activity could, in some cases, cause

negative results. Two students of the Indifferent

subgroup who expressed a negative opinion about

ranking in the questionnaire said that they did not

like the competitive aspect injected in the activity by

the rankings, and this was the reason they ignored

them completely. Checking the activity logs for

these two students and their scores in post-test, we

saw that they were both above the average of their

subgroup, while one of them was also in the top 10

positions in different usage metrics. On the opposite

side, a student of the InFavor group actively tried to

stay in the top positions throughout the activity and

she managed to do so for most of the metrics of the

study (Logins: 66; Views: 43; Reviews: 3; Peer

Score: 3.53; Post-test: 7.80). So, while this student

had visited the learning environment double the

times of the InFavor average and had viewed (or at

least visited) 43 out of the total 51 available peer

work, she only submitted the minimum number of

reviews and was well below average in the scores

she received on her initial answers from peers and

on the post-test from the two raters. From our point

of view, this student lost the actual focus of the

activity (acquire domain knowledge and develop

review skills) and focused on improving her

rankings. The short periods of time recorded for

each peer work view for this student also suggest

that her engagement in the activity was superficial.

This behavior is very close to what Baker et al.,

(2008) define as “gaming the system”, namely an

effort to succeed by actively exploiting the

properties of a system, rather than reaching learning

goals.

These three cases were the extremes in our

analysis, but they still provide insights into how

under certain circumstances ranking information

could have the opposite effect an instructional

designer is looking for. In addition to this, students

also mentioned that a low ranking in the Peer Score

would alarm them into improving their initial work,

while some students also mentioned that a high

position in this metric was reassuring. The issue here

lies on the fact that sometimes students’ and raters’

opinions about the quality of a work do not match.

Students that relied only on the ranking information

may be misled.

In conclusion, providing students with ranking

information could be beneficial for them, especially

when students develop a positive attitude towards

having this information. In these cases, students’

intrinsic motivation is increased and engagement is

enhanced. However, attention is also needed on how

students act during the learning activity. In certain

cases, chasing after rankings could cause negative

attitudes or superficial engagement.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A

Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A

Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational

Objectives. NY: Longman.

Baker, R., Walonoski, J., Heffernan, N., Roll, I., Corbett,

A., & Koedinger, K. (2008). Why Students Engage in

“Gaming the System” Behavior in Interactive

Learning Environments. Journal of Interactive

Learning Research. 19 (2), pp. 185-224. Chesapeake,

VA: AACE.

Demetriadis, S. N., Papadopoulos, P. M., Stamelos, I. G.,

& Fischer, F. (2008). The Effect of Scaffolding

Students’ Context-Generating Cognitive Activity in

Technology-Enhanced Case-Based Learning.

Computers & Education, 51 (2), 939–954. Elsevier.

Denny, P. (2013). The effect of virtual achievements on

student engagement. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

ACM, 2013.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defining

"gamification". In Proceedings of the 15th

International Academic MindTrek Conference:

Envisioning Future Media Environments (MindTrek

'11). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 9-15.

Goldin, I. M., & Ashley, K. D., (2011). Peering Inside

Peer-Review with Bayesian Models. In G. Biswas et

al. (Eds.): AIED 2011, LNAI 6738, pp. 90–97.

Springer-Verlag: Berlin.

Hansen, J., & Liu, J. (2005). Guiding principles for

effective peer response. ELT Journal, 59, 31-38.

Li, L., Liu, X. & Steckelberg, A.L. (2010). Assessor or

assessee: How student learning improves by giving

and receiving peer feedback. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 41(3), 525–536.

Liou, H. C., & Peng, Z. Y. (2009). Training effects on

computer-mediated peer review. System, 37, 514–525.

Lundstrom, K., & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than

to receive: The benefits of peer review to the

reviewer’s own writing. Journal of Second Language

Writing, 18, 30-43.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

146

Luxton-Reilly, A. (2009). A systematic review of tools

that support peer assessment. Computer Science

Education, 19:4, 209-232.

Martinez-Mones, A., Gomez-Sanchez, E., Dimitriadis,

Y.A., Jorrin-Abellan, I.M., Rubia-Avi, B., & Vega-

Gorgojo, G. (2005). Multiple Case Studies to Enhance

Project-Based Learning in a Computer Architecture

Course. Education, IEEE Transactions on, 48(3), 482-

489.

McConnell, J. (2001). Active and cooperative learning.

Analysis of Algorithms: An Active Learning

Approach. Jones & Bartlett Pub.

Norris, M. & Pretty, S. (2000). Designing the Total Area

Network. New York: Wiley.

Papadopoulos, P. M., Demetriadis, S. N., & Stamelos, I.

G. (2009). Analyzing the Role of Students’ Self-

Organization in Scripted Collaboration: A Case Study.

Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on

Computer Supported Collaborative Learning – CSCL

2009 (pp. 487–496), Rhodes, Greece. ISLS.

Papadopoulos, P. M., Lagkas, T. D., & Demetriadis, S. N.,

(2012). How to Improve the Peer Review Method:

Free-Selection vs Assigned-Pair Protocol Evaluated in

a Computer Networking Course. Computers &

Education, 59, 182 – 195. Elsevier.

Papadopoulos, P. M., Lagkas, T. D., & Demetriadis, S. N.,

(2015). Intrinsic versus Extrinsic Feedback in Peer-

Review: The Benefits of Providing Reviews (under

review).

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer support

for knowledge-building communities. The Journal of

the Learning Sciences, 3(3), 265-283.

Turner, S., Pérez-Quiñones, M. A., Edwards, S., & Chase,

J. (2010). Peer review in CS2: conceptual learning. In

Proceedings of SIGCSE’10, March 10–13, 2010,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA.

TheImpactofRankingInformationonStudents'BehaviorandPerformanceinPeerReviewSettings

147