Humanizing the Internet of Things

Toward a Human-centered Internet-and-web of Things

Antonio Pintus, Davide Carboni, Alberto Serra and Andrea Manchinu

CRS4, Loc. Piscina Manna Ed.1, Pula, Sardinia, Italy

Keywords: Internet of Things, Web of Things, IoT, WoT, People, IoP, Web Platforms, Social.

Abstract: This paper envisions how the Internet of Things (IoT) complements the Internet of People to build a human-

centered Internet-and-Web of Things. The Internet of Things should go beyond the Machine-to-Machine

paradigm and must include people in its foundation, resulting in a “Humanized Internet of Things (H-IoT)”.

Starting from a relevant work of Fiske, this paper defines how the Human-centred Internet of Things can

embed the Fiske patterns in this particular domain. An analysis of some of existing IoT platforms and

projects is also presented with the aim to analyse how real implementations are in the same direction of such

social patterns.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today the Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the main

topics of discussion in the ICT world; it can be

defined as the interconnection of uniquely

identifiable embedded computing devices within the

existing Internet network. The IoT evolved to a

convergence of multiple technologies, ranging from

many different fields of application such as

industrial, health, Smart Grid and Smart Cities in

general covering the Machine-to-Machine (M2M)

paradigm. Until nowadays the main effort was to

create applications and platforms hardware oriented,

to improve devices connection and communication,

giving little importance to aspects related to the

user-experience, privacy and security policies. In

other words, giving little importance to the human

side of the Internet (of Things).

The aim of this work is to investigate an

alternative point of view that includes people in the

IoT loop to give a more human perspective to the

technology.

2 RELATED WORKS

Several works stressed the need for the IoT to go

beyond a pure Machine-to-Machine (M2M)

paradigm, in order to also include people. First steps

toward this aim have been connecting things in a

sort of extended social networks, the so called

“Social Internet of Things”, but it was originally a

concept where things were capable of establishing

social relationships with other objects and

autonomously with respect to humans (Atzori et al.,

2014). About this topic, other works focused in

using supernetwork theories (Cheng et al., 2014) to

model relationships between humans, things and

services, resulting in proposing models to create a

social network involving humans and things but with

a user experience and human interaction to improve

and further test. First fusion of traditional social

networks with data coming from sensors remarked a

potential, strict correlation between that world and

the IoT (Schmid and Srivastava, 2007); where other

works (Guinard, Fischer and Trifa, 2010) and

platforms (Paraimpu, 2015) not only extended this

paradigm of socializing things and produced data

through Facebook or Twitter, but also envisioned the

possibility to share these things with people in a

social circle and to use them for their personal aims.

That vision of a social IoT could be seen as a

declination of the Sharing Economy and

Collaborative Consumption (Botsman and Rogers,

2010) paradigms (Pintus, Carboni and Piras, 2011).

3 HUMANIZING THE INTERNET

AND THE WEB OF THINGS

In earlier IoT research, its related definitions,

scientific papers and scenarios remarked the

498

Pintus A., Carboni D., Serra A. and Manchinu A..

Humanizing the Internet of Things - Toward a Human-centered Internet-and-web of Things.

DOI: 10.5220/0005475704980503

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2015), pages 498-503

ISBN: 978-989-758-106-9

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

property of a new way to automate daily processes

involving “things” with a little or no human

intervention at all.

Nowadays, on the other hand, we believe that the

IoT deeply involves people interaction with things

and devices, at least in every day scenarios, like

training, health, home appliances automation and so

on.

As stated in an interesting work (Wilson, 2014),

in a human-friendly IoT vision, involved things need

to talk to other things we use, be conspicuous and

attractive and go beyond remote controlling them.

These assumptions are a good starting point and

we state that a Humanized Internet of Things (H-

IoT) includes the “classic definition” of IoT

(basically M2M-focused) plus the Social Internet of

Things (S-IoT) and the Internet of People (IoP),

going toward the concept of the Internet and the

WWW as an extraordinary means enabling

interactions between communicating entities: smart

things and people, the physical world and the digital

one.

There is plenty of scientific literature about

technology in IoT, while in this paper we focus on

human and organizational perspective. On the other

hand, despite we believe that a user-centered design

of IoT applications should be taken into

consideration to complete the H-IoT concept, in this

paper we do not face Human-Computer Interaction

aspects, which are accurately analyzed in

(Koreshoff, Leong, and Robertson, 2013).

3.1 The Social Internet of Things and

the Internet of People

In this paper we define a new domain for social

interactions pattern as introduced by Fiske (Fiske,

1992). In his relevant psychological work, Fiske

identified four common forms or models of sociality

that people use in their relations. Each model is

distinct in the rules and values of how people

interact. These patterns are: Communal Sharing

(CS), Authority Ranking (AR), Equality Matching

(EM) and Market Pricing (MP).

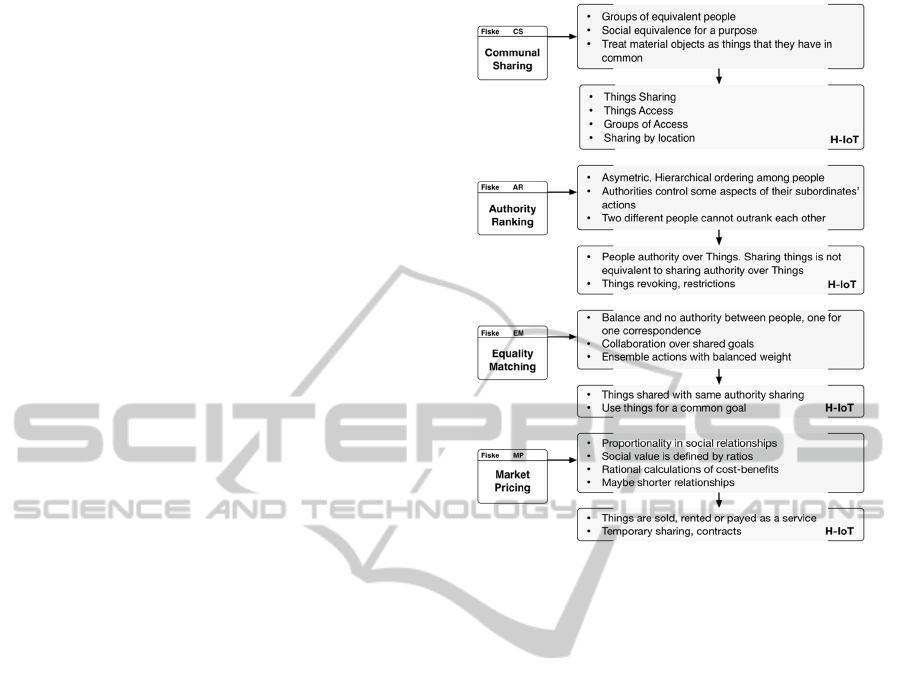

Figure 1 shows how Fiske’s model can be

mapped to the social aspects of a H-IoT, remarking

the main features of each pattern and how them

relate to equivalent ones in our specific domain.

A deep analysis of Fiske’s forms goes beyond

the aims of this work; they are applicable to many

domains, but what we want to shape here is if and

how they can be shifted and projected toward our

idea of a H-IoT, stressing where these model of

sociality can naturally include Things and People.

Figure 1: Fiske’s Four Elementary Forms of sociality

projected to a Humanized Internet of Things.

In our view, a social H-IoT exposes all the

elementary forms of sociality between people but it

adds a new layer: Things over the Internet/Web.

People interact with things and devices; people use

Fiske’s similar patterns to establish social actions

and group goals with other people through things. In

this domain, Fiske’s Communal Sharing is adapted

to a totally trusted sharing of things, where a person

let all persons in the community to use his/her smart

things, such permission is not revocable in principle

and the other persons have the same level of control

of the owner because of mutual trust. So, for

example, a person could share its connected smart-

TV with his/her friends and family members because

of the strict level of trust; or he/she can create

groups of social equivalence in sharing home things;

for example, some devices can be used only by

family members, whereas others also by hosts.

In the domain of the IoT, the Authority Ranking

pattern is built around an authority, maybe

hierarchical: things and related Internet resources

can be shared but not the authority over them.

Things owners can set restrictions and/or revoke the

social interaction between a thing and another

person. Thus, most of the authority is in the hand of

a single actor while the others have least-authority.

Again, in this IoT domain, the Fiske’s Equality

HumanizingtheInternetofThings-TowardaHuman-centeredInternet-and-webofThings

499

Matching form is adapted to shape a collaboration of

people sharing smart things for a specific goal. For

example, adopting a weighted one for one

correspondence people could use environmental data

observed by shared sensors to build together a new

distributed application for pollution alerts in a city,

with no authority over these relations and with a

good balance between benefits and contributions.

Finally, adapting the Fiske’s Market Pricing

pattern requires a transaction-based model over

exchanges and things sharing, providing a definition

of rational cost-benefits calculation over things

usage; For example, we can think about it as smart

devices renting, or an IoT platform sold as-a-

Service, where also contracts and specific terms-of-

service could rule this type of relationship.

A H-IoT tool should expose one or more of these

features, theoretically tracing an equivalent form of

natural social relationship patterns between people.

A good definition of IoP we like can be found in

(Vermesan et al., n.d), where the IoP is defined as

the interconnects growing population of users while

promoting their continuous empowerment,

preserving their control over their online activities

and sustaining free exchanges of ideas. The IoP also

provides means to facilitate everyday people’s life,

communities and organizations, allowing at the same

time the creation of any type of business and

breaking the barriers between an information

producer and an information consumer (the

emergence of prosumers).

Another definition of IoP is proposed in

(Hernández-Muñoz et al., 2011) and it is envisaged

as people becoming part of ubiquitous intelligent

networks having the potential to seamlessly connect,

interact and exchange information about themselves

and their social context and environment.

The IoP and the S-IoT are strictly related in

overtaking the original M2M-related definitions of

the IoT: adopting a H-IoT people interconnect,

interact, socialize, create, communicate, make and

become prosumers (both producers and consumers)

through the Internet/Web of connected things and

people, implicitly using the IoT equivalent of the

Fiske’s four elementary forms of sociality. That’s

the new era of the Internet: a Humanized Internet (of

Things).

But, to go toward a real H-IoT it is mandatory to

take into consideration how the four H-IoT patterns

can be managed. From a technical point of view,

using some form of digital contract or policy could

shape the patterns. The policies should be flexible

enough to cover the four aspects described above

and, of course, they involve a balance between

identities and privacy, authorities and trust, rules and

permissions.

3.2 Implementing the Social Patterns in

the H-IoT Domain

This section addresses some more detailed

descriptions of the Internet of Things domain as a

new one in the Fiske classification. For each social

pattern the issues and possible high-level technical

solutions are broadly described. In the next sections

some existing Internet platforms for smart Things

are then evaluated against these features.

3.2.1 Communal Sharing

In this pattern the level of trust is the highest as the

smart things are in principle controllable and

shareable by everyone in the community. Building a

community of trusted peers is then the point to face

here, and the balance between disclosing the

identities of peers and keeping their privacy is

important, too. Given the level of control on the

smart things, this management is similar to the

sharing of credential among a group of sys admin in

a computer system. In such a case there exists at

least one authority over the community, which

knows the identities of each peer, but inside the

community the hierarchy is flat and every participant

is equally entitled to manage the resources. The

community manager is commonly a trusted entity

with a known identity. The community manager is

not required in cases like a community is

spontaneously formed by means of contextual fact.

For example, people and device inside a given place

forms a “community” because their mere presence is

a proof of trust in that context.

3.2.2 Authority Ranking

In this pattern a person with a particular authority

(e.g., ownership) shares things with other people but

he/she doesn’t share the authority over them. Thus,

the set of defined rules in resulting digital

environments development must ensure that

authority can not be changed by people down on the

established hierarchy; for example, by people who

are not owners of a shared thing. Authority must

have the choice to change policies, too. In this case,

social circles or groups are formed because people

follow an acknowledged leader: identified by social

influence, value of shared things and resources, level

of influence in a specific community or by technical

skills.

WEBIST2015-11thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

500

3.2.3 Equality Matching

To extend this pattern to the domain of the Internet

of Things we could start from the definition in the

domains of work and contribution in (Fiske, 1992).

The idea is that every peer contributes in a balanced

way eventually to reach common goals. As example

we could imagine a use case in which an actor

contributes with a temperature sensor, while another

with a noise sensor, and a third one contributes

developing a software application that elaborates

data from the sensors and provides new information

with value for the local environment. The three

actors are not establishing a hierarchy but they are

pursuing a common goal where each one is equally

contributing and equally getting some benefits.

When speaking of Internet-related resources, the

point is how to measure the “equality” of each

contributor in order to keep the balance among

peers. What if one of the contributions is

quantitatively much bigger or much lower than the

others? To manage the above points a distributing

approval process could be deployed. In other words

the individual feeling that some of the other

contributions are unfair should be able to choose

either to withdraw the group or to promote an action

to ban the participant who are not providing enough

value by starting a remote voting.

3.2.4 Market Pricing

This pattern is based on the existing infrastructure of

a market. Products pages, shopping carts and back-

office processes are the key elements of this pattern

in order to serve orders from the purchase to the

final delivery. In the field of the Internet of Things it

should be defined what is finally sold. At one end

there are manufactures that sell physical objects, in

other words they sell the smart things and then

publish on an app store like Apple Store or Google

play some free-apps. Often, the real value is not in

the hardware but in the software, even if this is given

for free. As example, we mention the case of iRig™,

a special purpose cable which allows to add real

time effects to an electric guitar. The valuable part is

the software, which is given for free from the App

store, but the revenues come from cables shipping.

At the opposite end, there are markets, which do not

sell the physical stuff, but sell some form of digital

asset for one or more hardware platform. Glue.things

is an example of this concept. In this platform users

can register their smart objects, design applications

and event management processes, and finally share

and trade their applications in a dedicated market.

3.3 Comparison of Existing IoT Web

Tools and Platforms

To analyse the impact of the Fiske’s model and to

discover its application, we seek the four patterns in

a number of tools and platforms already available on

the Web. Here follows a short analysis of major

platforms. The analysis is aimed at classify if a

platform is more inclined to one or more Fiske

patterns as we have previously informally defined

for the domain of IoT.

IFTTT (If This Than That) (IFTTT, 2015) is a Web

platform that allows users to automatize tasks on the

Internet. For instance, the user can define a rule

(called “recipe”) to manage an event coming from

one device and under a given condition to perform

an action on another system (a device or a web

service). Its main advantages are easiness of use,

recipe sharing between users and a large set of

available services/devices.

In IFTTT it is not possible to share things, so a

Communal Sharing seems not applicable, however it

is possible to share recipes as templates to define

personalized actions for a specific goal, thus recipes

goes toward an incomplete Equality Matching

pattern because only goals are shared but not things

as means to fulfil them.

Paraimpu (Paraimpu, 2015) provides a personal

workspace where users can register devices

providing a basic level of virtualization. An

integrated transformation engine allows composing

things managing their heterogeneity. It has a good

balance between simplicity of use and flexibility,

social-ability and things sharing (Pintus, Carboni

and Piras, 2012). Paraimpu partially supports the

Communal Sharing pattern because it is not possible

to create fine-grained social circles; however, when

things are shared as “public” they are available to

use to all the people belonging to a person’s social

circle. Paraimpu implements the Fiske’s Authority

Ranking model: authority over things is enforced

and cannot be changed by people whose not own a

particular thing. The platform enables Equality

Matching pattern because people can share things

and data with other users to build “cooperative”

applications to fulfil a particular shared goal.

Xively (Xively, 2015) provides a platform, services

and support needed to create and manage connected

products and services on the IoT. It provides a basic

workspace and it’s more developer-oriented than the

other tools, thanks to a good, consistent, set of

libraries. The set of available tools are really

oriented toward a company-to-product-to-customer

model, so things sharing and related patterns could

HumanizingtheInternetofThings-TowardaHuman-centeredInternet-and-webofThings

501

be applied in an intra-company environment, where

people belonging to a company (in this case: the

social circle) use Fiske patterns to reach a particular

goal, that is: to produce and to sell products.

Equality Matching can be not directly implemented

through provided API and credentials.

SocIoTal (SocIoTal, 2015) aims to design and

provide key enablers for a reliable, secure and

trusted IoT environment. It will enable the creation

of a socially aware citizen-centric Internet of Things

by encouraging people to contribute with their IoT

devices and information flows.

By providing communities with secure and trusted

tools that increase user confidence in IoT

environment, SocIoTal will enable their transition to

smart neighbourhood, communities and cities.

SocIoTal supports Communal Sharing pattern

because each person has a number of different trust

zones or communities. A trust zone represents a

group of people or objects that can access the

resources in the community. Participants can decide

at any time to leave the community revoking any

previous access to the other participants.

SocIoTal presents also a form of Authority Ranking

model: information sharing and data access have the

primary role to limit and control the access to data or

resources.

This platform also enables the Equality Matching

pattern. That’s because the entire project is finalized

to share things, create a community of trust and

reach a common result. An example of this pattern is

represented by the description of the project use

cases like “Car Pooling” (N. Gligoric et al., 2014).

Glue.things (Glue.things, 2015) is a Platform-as-a-

Service (PaaS) designed for applications and

services for the Internet of Everything. It sells some

form of digital assets for one or more hardware

platforms. In this platform users can register their

physical smart objects and connect them with other

virtual objects, can design apps and event

management processes, and finally share and trade

their apps in a dedicated market.

There is a smart objects marketplace that gives to the

user the chance to distribute and share the output

data of his/her devices and his/her applications with

the community. This market provides flexible

revenue models, which clearly focus on the means of

your target groups. Glue.things supports Fiske’s

Market Pricing pattern allowing enterprises and

innovators to introduce new Internet of Things

enabled services and apps in a short time and with

limited upfront investment.

The platform also partially supports Communal

Sharing pattern, sharing smart objects data and apps

to the developer community through the

marketplace. There is no implementation of the

Equality Matching because people cannot share,

contributing in balanced way, smart objects to reach

a common goal.

Authority Ranking pattern is partially implemented

because people can share apps and data selling it

through the market and sharing the authority over

them.

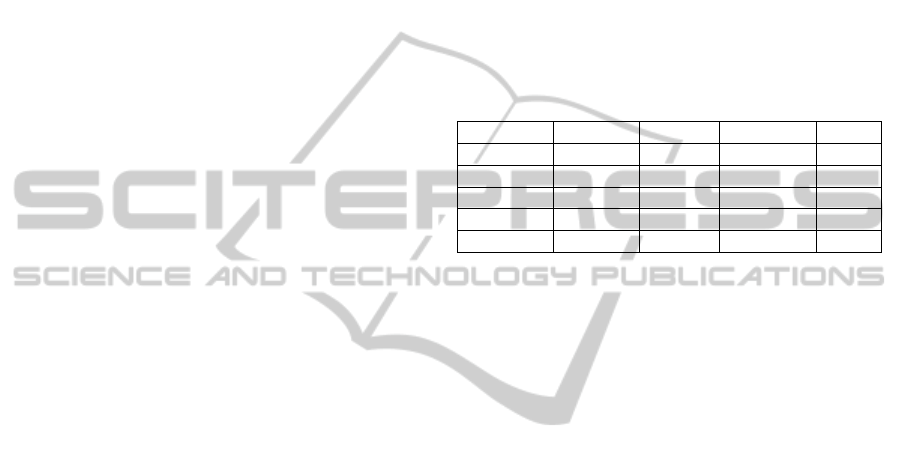

The following Table 1 summarize the comparison

between the selected tools/platforms described and if

they match the four patterns of Fiske in the H-IoT:

Table 1: Comparison of some existing Web tools and

platforms with respect to the envisioned H-IoT properties.

CS AR EM MP

IFTTT No No Partially No

Paraimpu Partially Yes Yes No

Xively Partially Yes Not directly No

SocIoTal Yes Yes Yes No

Glue.things Partially Partially No Yes

The indications on the Table could suggest which

one of these common IoT platforms to date is more

ready for the H-IoT than the others.

4 FUTURE WORKS AND

CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we describe a socially-centered model

where Internet of Things applications are be

confined to Machine-to-Machine technology issues.

In this respect, people and sociality patterns are a

key factor for the emergence of a Humanized

Internet of Things (H-IoT).

These considerations led us to examine not only

a user-centered design, which is not covered in this

paper, but also to dissect an implementation of the

common basic patterns of human sociality defined

by Fiske in his famous work. We have extended

Fiske work introducing the IoT domain as a new one

in the Fiske classification. For each social pattern,

the issues and possible high-level technical solutions

are broadly described together with some

suggestions about their implementation in a real IoT

application or platform.

Fiske’s model projection to the IoT domain is

interesting because all processes involving people

sociality could build a conceptual framework to

better envision and design the IoT of the future.

Trying to find an actual implementation of

Fiske’s models toward a real H-IoT guided us to a

basic set of lesson learned and recommendations

WEBIST2015-11thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

502

about open issues in IoT platforms. Then, we

examined some of the existing platforms, checking

their adherence to the envisioned H-IoT model and,

as remarked, none of them fully support the four

transposed Fiske patterns, maybe due to specific

business models or market targets. Anyway, some of

them seem very promising toward a better H-IoT

adherence. Future works will refine the explored H-

IoT concepts to provide a full conceptual framework

and recommendation to build socially-aware and

Fiske-complete systems.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper describes work undertaken in the context

of the SOCIOTAL project (www.sociotal.eu).

SOCIOTAL is a Collaborative Project supported by

the European 7th. Framework Programme, contract

number: 609112.

REFERENCES

L. Atzori, D. Carboni, A. Iera, Jul 2014. “Smart things in

the social loop: Paradigms, technologies, and

potentials” in Ad Hoc Networks, 2014, Vol 18, pp.

121-132, doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2013.03.012.

C. Cheng, C. Zhang, X. Qiu, Y.Ji, Feb. 2014. “The Social

Web of Things (SWoT)- Structuring an Integrated

Social Network for Human, Things and Services” in

Journal of Computers, Vol 9, No 2 (2014), pp. 345-

352, doi:10.4304/jcp.9.2.345-352.

T. Schmid and M. B. Srivastava, Nov. 2007. “Exploiting

Social Networks for Sensor Data Sharing with

SenseShare,” CENS 5th Annual Research Review.

D. Guinard, M. Fischer, and V. Trifa, Mar. 2010. Sharing

using social networks in a composable web of things.

In Proc. of the First IEEE International Workshop on

the Web of Things (WOT2010), Mannheim, Germany.

R. Botsman and R. Rogers, 2010. “What’s Mine Is Yours:

How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way

We Live: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption”,

Harperbusiness.

A. Pintus, D. Carboni, A. Piras 2011. "The anatomy of a

large scale social web for internet enabled objects",

Proceedings of the Second International Workshop on

Web of Things ACM WoT '11 pages 6:1–6:6 New

York, NY USA.

H. James Wilson, “Make the Internet of Things more

Human-Friendly”, Oct. 2014. Harvard Business

Review, Blog. Available from:

http://blogs.hbr.org/2014/10/make-the-internet-of-

things-more-human-friendly/.

T.L. Koreshoff, T.W. Leong, T. Robertson, 2013.

“Approaching a Human-Centred Internet of Things”,

OZCHI’13, November 25–29, Adelaide, SA,

Australia.

A. P. Fiske, 1992. "The four elementary forms of sociality:

framework for a unified theory of social relations",

Psychological Review, vol. 99.

O. Vermesan, P. Friess, P. Guillemin, S. Gusmeroli, H.

Sundmaeker, A. Bassi, I. S. Jubert, M. Mazura, M.

Harrison, M. Eisenhauer, P. Doody, “Internet of

Things Strategic Research Roadmap”, Available from:

http://www.internet-of-things-

research.eu/documents.htm.

J. M. Hernández-Muñoz, J. B. Vercher, L. Muñoz, J. A.

Galache, M. Presser, L. A. Hernández Gómez, J.

Pettersson, 2011. “Smart Cities at the Forefront of the

Future Internet” Future Internet Assembly 2011:

Achievements and Technological Promises; Lecture

Notes in Computer Science Volume 6656, pp 447-462.

A Pintus, D Carboni, A Piras, Apr. 2012. “Paraimpu: a

platform for a social web of things.” Proceedings of

the 21st international conference companion on World

Wide Web. Lyon, France.

N. Gligoric, S. Krco, I. Elicegui, C. López, L. Sánchez, M.

Nati, R. Van Kranenburg, M. V. Moreno, D. Carboni,

March 2014. SocIoTal: Creating a Citizen-Centric

Internet of Things, 4th International Conference on

Information Society and Technology (ICIST 2014), 9-

13.

Paraimpu, a social tool to allow people to connect,

compose and share Things. Available from:

https://www.paraimpu.com. [27 January 2015].

Glue.things. Available from: http://www.gluethings.com.

[27 January 2015].

IFTTT, web-tool to connect services and things with the

statement “if this then that”. Available from:

https://ifttt.com. [27 January 2015].

Xively, IoT platform as a service for the IoT. Available

from: https://xively.com. [27 January 2015].

SocIoTal, an EU FP7 funded STREP project, “A reliable,

smart and secure Internet of Things for Smart Cities”

Available from: http://sociotal.eu. [27 January 2015].

HumanizingtheInternetofThings-TowardaHuman-centeredInternet-and-webofThings

503