Utilitarian Value and Hedonic Value of Mobile Service

Focusing on Mobile Addiction

Soon Jae Kwon

Department of Business Adminstration, DAEGU University, Kyong San, Korea

Keywords: Mobile Service, Mobile Addiction, Utilitarian Value, Hedonic Value, Fun, Moderating Effect.

Abstract: Mobile addiction (MA) has become more prevalent nowadays especially with the advancement of mobile

services. This study is focus on studying MA in the context of users’ perceived hedonic and utilitarian

values. This is done by empirically analysing the moderating effect of MA against three constructs which

are users’ perceived hedonic value (PHV), perceived utilitarian value (PUV), perceived usefulness (PU) and

fun experienced by using mobile service. A total of 166 participants were involved in the survey. The results

showed that only the relationship between perceived hedonic value and fun was not moderated by mobile

addiction. Meanwhile, the rest of the hypothesized relationships were supported.

1 INTRODUCTION

The wide usage of mobile devices are mostly

supported by various mobile services such as short

message service (SMS), digital multimedia

broadcast (DMB), wireless Internet, and

entertainment applications, such as wireless online

games and music. Mobile service can have either

hedonic or utilitarian value to potential users, and it

is necessary to consider both values when

investigating user acceptance of mobile service.

Deci (1975) suggested that user acceptance is

determined by two fundamental types of motivation

which is extrinsic and intrinsic. An extrinsically

motivated user is driven by the expectation of a

reward or benefit external to system-user interaction

(perceived usefulness), while an intrinsically

motivated user is driven by benefits derived from

system-user interaction (perceived fun). Igbaria et al.

(1994, 1996) found system usage to be affected by

both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation and Bruner II

and Kumar (2005) introduced fun in the user

acceptance model of handheld Internet devices. The

development of mobile technology means users can

afford to use fancier mobile equipment and enjoy

higher quality mobile services, regardless of time

and place. However, easy access to high-quality

mobile service may lead users to a compulsive usage

state, mobile addiction (MA). The primary purposes

of this study are as follows. Firstly, assume that

mobile users have at least one of two values which

are hedonic or utilitarian. Secondly, the moderating

effect of MA is analysed to see its effect on mobile

users’ intention to use mobile services.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUNDS AND

RESEARCH MODEL

2.1 Utilitarian/Hedonic Values

Consumer behaviour literature has demonstrated that

specific determination of intention to consume

depends on the utilitarian or hedonic attributes of the

product (Babin et al. 1994; Okada 2005). Based on

this finding, this study concluded that user intention

to use mobile service is shaped by the utilitarian or

hedonic value derived from their experience using

mobile services (Chiu et al. 2005). Users’ perceived

value of mobile services is therefore defined as

perceived utilitarian value and perceived hedonic

value. In general, an IS possesses various utilitarian

attributes, and users perceive the usefulness of

utilitarian attributes while experiencing the IS

(Adams et al. 1992). It has also been found (Babin et

al. 1994; Okada 2005; Voss et al. 2003) that the

utilitarian value of products and services influences

consumers’ perceived usefulness, ultimately

affecting consumer behaviour. This is proposed by

the following hypotheses:

H1: Perceived utilitarian value of mobile service

has a positive influence on perceived usefulness.

621

Jae Kwon S..

Utilitarian Value and Hedonic Value of Mobile Service - Focusing on Mobile Addiction.

DOI: 10.5220/0005476106210626

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2015), pages 621-626

ISBN: 978-989-758-106-9

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

H2: Perceived usefulness of mobile service has a

positive influence on intention to use mobile service.

On the other hand, users tend to experience

intrinsic motivation (Davis et al. 1992) or fun (Babin

et al. 1994; Voss et al. 2003) strongly when they

perceive hedonic value on particular IS/ITs (Bruner

II and Kumar, 2005). According to Okada (2005),

users justify their use of products by continuing to

consume them once they perceive fun is connected

to hedonic value. Therefore, mobile users will

perceive fun in their mobile service if they

experience a particular hedonic value about that

service:

H3: Perceived hedonic value of mobile service

has a positive influence on fun.

2.2 Fun

Triandis (1971) argued that affect, the feelings of

joy, elation, pleasure, depression, disgust,

displeasure, or hate associated with a particular act,

have an impact on a person's behaviour. Sandelands

et al. (1983) found that such attitudinal outcomes of

positive affect, pleasure, and satisfaction are results

from playful experiences. Therefore, individuals

who perceive using mobile service as fun will have a

positive intention about using them:

H4: Perceived fun in using mobile service will

positively affect intention to use mobile service.

2.3 Mobile Addiction

MA is related to a type of addictive behaviour

defined (Mendelson and Nancy, 1986) as behaviour

that is excessive, compulsive, beyond the control of

the person who engages in it, and destructive

psychologically or physically. Li and Chung (2006)

suggested that Internet addictive behaviour is

affected by psychopathology factors such as

depression and anxiety and personality factors such

as neurosis, openness, and consciousness. Davis

(2001) used the cognitive-behaviuor model to

explain pathological Internet use, which is similar to

Internet addictive behaviour. Similarly, MA can also

be defined as compulsive consumption. O'Guinn and

Faber (1989) define MA as a response to an

uncontrollable drive or desire to obtain, use, or

experience a feeling, substance, or activity that leads

an individual to repetitively engage in a behavior

that will ultimately cause harm to himself and/or

others.

Terel, Serenko and Giles (2011) studied the online

auction addiction. According to their study, the level

of addiction distorts the way information technology

artifact is perceived. In this study, MA is a

moderating variable used to analyse mobile service

users’ acceptance behaviour. As users are affected

by their addiction, it is expected that their perception

towards mobile services will also be affected.

Therefore, the following hypotheses are related to

MA as moderating variable:

H5-1: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship between

perceived utilitarian value and perceived usefulness.

H5-2: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship between

perceived hedonic value and fun.

H5-3: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship between

perceived usefulness and intention to use mobile

service.

H5-4: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship between fun

and intention to use mobile service.

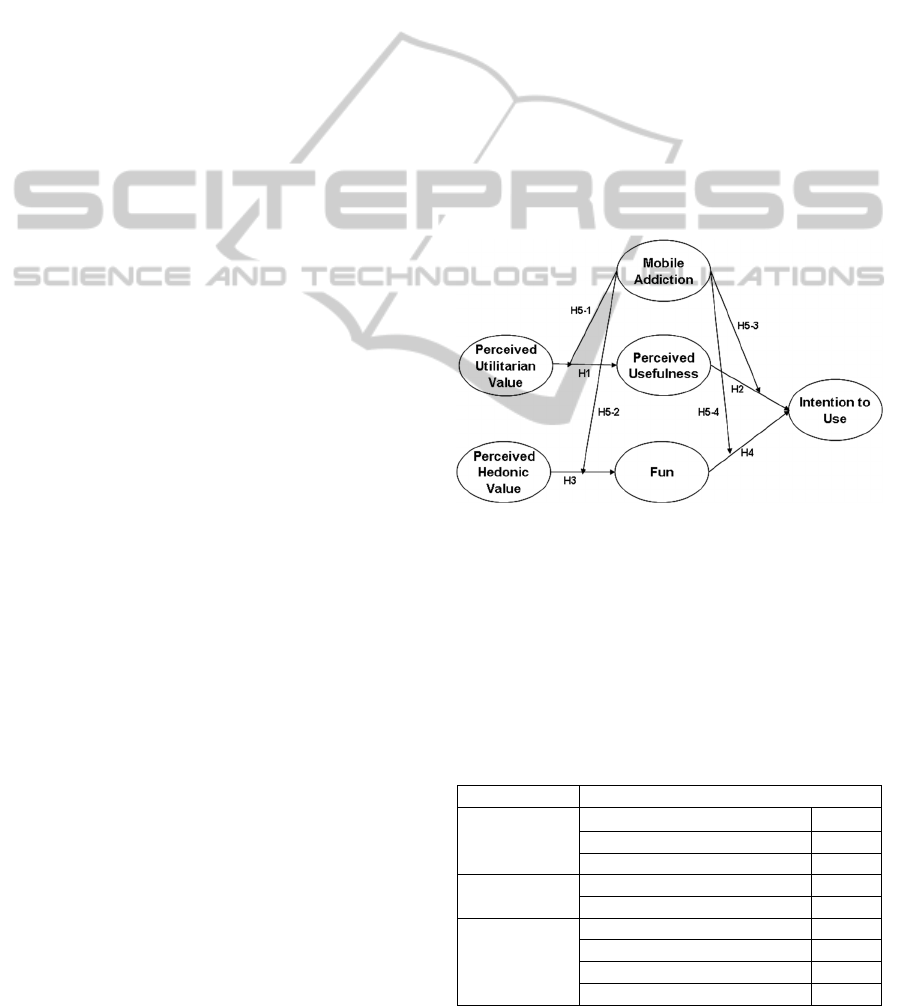

Figure 1: Proposed Research Model.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A survey was conducted to gather the necessary

user’s data among university students in South

Korea consisted of 166 respondents. Table 1 shows

the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Sample.

Variables Sample Composition

Age Group

20– 23 years old

36

24 – 26 years old 101

27 – 29 years old 26

Gender

Female 39

Male 127

Daily usage of

mobile device

1 – 3 hours 8

4 – 6 hours 44

7 – 9 hours 57

More than 10 hours 57

WEBIST2015-11thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

622

The measurements consisted of intention to use

(Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980), perceived usefulness

(Davis, 1989), fun (Venkatesh, 2000), MA (Charlton

and Danforth, 2007) and perceived hedonic and

utilitarian value (Voss et al., 2003). Partial least

square (PLS) was used to analyze the field survey

data because it places minimal restrictions on sample

size and residual distribution (Chin et al. 2003). PLS

employs a component-based approach for estimation

purposes (Lohmoller 1989). In general, PLS is better

suited for explaining complex relationships because

it avoids the problems of inadmissible solutions and

factor indeterminacy (Fornell and Bookstein 1982).

This study thus chose PLS to accommodate the large

number of variables and measuring the moderating

effects. The reliability, convergent and discriminant

validity of the instrument were first examined. Table

2 shows that all but one loading are larger than the

suggested threshold of 0.70 (Chin, 1998). Table 3

shows that all composite reliabilities are larger than

the suggested 0.70 and all AVE values are greater

than the suggested 0.50 indicating a good

convergent validity of the measurement model

(Barclay et al, 1995; and Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Table 2: Loadings and Cross-Loadings.

PUV PHV PU FUN MA IU

PUV1

0.828

0.417 0.477 0.317 -0.271 0.621

PUV2

0.874

0.515 0.549 0.420 -0.299 0.661

PUV3

0.755

0.450 0.341 0.447 -0.118 0.463

PUV4

0.861

0.508 0.407 0.497 -0.148 0.582

PUV5

0.873

0.514 0.441 0.520 -0.176 0.577

PHV1 0.525

0.811

0.264 0.725 -0.002 0.455

PHV2 0.538

0.864

0.355 0.630 -0.025 0.450

PHV3 0.458

0.868

0.211 0.562 0.049 0.412

PHV4 0.423

0.837

0.323 0.562 0.016 0.364

PHV5 0.471

0.873

0.292 0.646 0.035 0.483

PU1 0.394 0.327

0.829

0.235 -0.184 0.349

PU2 0.339 0.301

0.748

0.207 -0.140 0.214

PU3 0.498 0.233

0.867

0.233 -0.239 0.457

PU4 0.499 0.287

0.846

0.281 -0.295 0.478

FUN1 0.432 0.611 0.197

0.890

-0.045 0.403

FUN2 0.463 0.719 0.318

0.938

0.037 0.363

FUN3 0.526 0.713 0.288

0.930

-0.044 0.431

MA1 -0.195 0.033 -0.180 0.025

0.765

-0.134

MA2 -0.257 -0.092 -0.263 -0.143

0.792

-0.238

MA3 -0.201 -0.072 -0.238 -0.069

0.785

-0.110

MA5 -0.116 0.144 -0.049 0.111

0.675

-0.033

MA6 -0.239 0.039 -0.202 0.044

0.787

-0.223

MA7 -0.089 0.103 -0.118 -0.009

0.532

-0.119

MA8 -0.002 0.130 -0.128 0.103

0.607

0.102

MA9 -0.077 0.124 -0.191 0.121

0.700

-0.052

IU1 0.660 0.493 0.441 0.400 -0.205

0.949

IU2 0.659 0.455 0.450 0.402 -0.255

0.968

IU3 0.674 0.511 0.467 0.432 -0.123

0.929

Reliability was assessed using internal

consistency scores, calculated by composite

reliability scores. Compeau et al. (1999) suggested

that for sufficient discriminant validity to be present,

items should load more strongly on their own

constructs, and the average variance shared between

each construct and its measures should be greater

than the variance shared between the construct and

other constructs. This can be seen in Table 2 that

items load much highly on their own latent

constructs than on any other latent constructs (cross-

loadings).

Table 3: Composite Reliability, Averages Variance

Extracted, and Correlations of First-Order Constructs.

Construct CR AVE

Square Roots of AVEs & Correlations*

1 2 3 4 5 6

1.PUV 0.9220.7050.839

b

2.PHV 0.9290.724 0.572 0.851

b

3 PU 0.8940.678 0.538 0.340 0.823

b

4.FUN 0.9420.845 0.517 0.743 0.293 0.919

b

5.MA 0.8900.506-0.252 0.016 -0.273 -0.018 0.711

b

6.IU 0.9640.900 0.701 0.513 0.478 0.434 -0.204 0.949

b

CR: Composite Reliability, AVE: Average Variance, Extracted,

b

p < 0.01

* The diagonal elements are the square roots of the variance

shared between the constructs and their measurement (AVE).

In addition, Table 3 shows that the square roots

of all AVEs are much larger than all other cross

correlations. Chin (1998) mentioned that

discriminant validity is achieved when the square

root of the AVE or a particular construct is larger

than the correlations between it and the other

constructs. Jointly, these findings suggest adequate

convergent and discriminant validity.

The results from standardized PLS path

coefficients are shown in Figure 2. The results

showed that Hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 4 are supported.

Figure 2: PLS Results.

UtilitarianValueandHedonicValueofMobileService-FocusingonMobileAddiction

623

4 RESEARCH RESULTS

In order to test the moderating effects of Past

Experience, this study employed the PLS-PS

(product of sum) approach recommended by

Goodhue et al. (2003). The sums of the moderating

factor (Mobile Addiction) and four variables

(Perceived Utilitarian Value, Perceived Hedonic

Value, Perceived Usefulness and Fun) were

multiplied to generate the product of sums.

Then, a model including both direct and

moderating effects were examined and Hypotheses

5-1, 5-3 and 5-4 are supported. However, mobile

addiction does not have a moderating effect on the

relationship between perceived hedonic value and

fun, therefore Hypothesis 5-2 is not supported. The

formula recommended by Aguinis and Gottfredson

(2010) was used to compute the F-statistic and the

effect size (f

2

) is calculated by the formula suggested

by Mathieson et al. (2001). Meanwhile, the effect

size result was concluded based on the suggestion by

Figure 3: Direct effect and moderating effect.

Cohen (1988) that 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 as operational

definitions of small, medium and large effect sizes

respectively. The steps taken to calculate the results

are shown in Figure 3. Meanwhile, the overall

results of the structural model are presented in Table

4.

Table 4: Results of the Structural Model.

Directs Effects

Direct Effects +

Moderating Effects

a. Dependent variable: PU; Independent variable: PUV

R

2

0.551 0.317

∆R

2

0.234 (f

2

= 0.043)

PUV 0.535 0.482

PUV x MA -0.133

b. Dependent variable: Fun; Independent variable: PHV

R

2

0.552 0.557

∆R

2

0.005(f

2

= 0.011)

PHV 0.743 0.725

PHV x MA 0.072

c. Dependent variable: IU; Independent variable: PU

R

2

0.234 0.316

∆R

2

0.082(f

2

= 0.107)

PU 0.484 0.425

PU x MA -0.261

d. Dependent variable: IU; Independent variable: Fun

R

2

0.191 0.248

∆R

2

0.057(f

2

= 0.070)

Fun 0.437 0.423

Fun x MA -0.021

Consequently, the results of hypothesis testing

are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Summary of Hypotheses Testing.

Hypotheses Supported?

H1: Perceived utilitarian value of

mobile service has a positive influence

on perceived usefulness.

Yes

H2: Perceived usefulness of mobile

service has a positive influence on

intention to use mobile service.

Yes

H3: Perceived hedonic value of mobile

service has a positive influence on fun.

Yes

H4: Perceived fun in using mobile

service will positively affect intention

to use mobile service.

Yes

H5a: Mobile addiction has a negative (-

) moderating effect on the relationship

between perceived utilitarian value and

perceived usefulness.

H5b: Mobile addiction has a negative (-

) moderating effect on the relationship

between perceived hedonic value and

fun.

Partially

supported. H5b is

not supported as

the effect size is

not significant.

However, H5a,

H5c and H5d are

supported.

WEBIST2015-11thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

624

Table 5: Summary of Hypotheses Testing (cont.).

Hypotheses Supported?

H5c: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship

between perceived usefulness and

intention to use mobile service.

H5d: Mobile addiction has a negative (-)

moderating effect on the relationship

between fun and intention to use mobile

service.

Partially

supported. H5b

is not supported

as the effect size

is not

significant.

However, H5a,

H5c and H5d are

supported.

5

DISCUSSION AND LIMITATIONS

This paper investigated the two important values in

user acceptance of mobile services, which are

utilitarian and hedonic value. The results gathered

shown that all investigated relationships are

supported. Both utilitarian and hedonic values are

critical perceived values in evaluating users’

acceptance of mobile services. Functionality as well

as the aesthetic value of a mobile service plays a role

in determining users’ acceptance. Therefore, mobile

service providers should consider both values when

developing new services. Secondly, this paper also

investigated the moderating effect of mobile

addiction on all the relationships proposed. The

results gathered shown that three out of the four

relationships are moderated by mobile addiction.

The relationship that was not moderated by mobile

addiction is the relationship between perceived

hedonic value and fun. This means that even if a

user is addicted to their mobile, the results show that

it will not be affecting the relationship between

perceived hedonic value and fun. Instead this

relationship is only effected by users perception of

how fun and enjoyable they are rather than because

they are addicted.

There are a few limitations in this study. As the

participants are university students, factors such as

flexible time could make it easier for them to be

addicted to a mobile service compare to full-time

workers. Furthermore, factors that make them

addicted to mobile service may also be different

compare to different group of users since they may

be exposed to different kind of services. Therefore,

mobile addiction among students is expected to be

more common compare to other group of users.

Secondly, rather than defining mobile service in

general, this study could come out with a better

results if focusing on only one mobile service.

However, this study’s results still are useful in order

to further develop a better study on mobile addiction

in the future.

6

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has highlighted the mobile addiction in

using mobile services. It is important to understand

that the availability of mobile services regardless of

place and time lead to development of addiction

between users and their mobile services. The most

interesting finding in this paper is that moderating

effect does not exist for relationship between

perceived hedonic value and fun. Since perceived

hedonic value is related to intrinsic motivation,

addiction does not have any effect on this

relationship. Instead it is effected by users

perception of having fun and enjoying themselves

rather than because they are addicted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Ministry of

Education of the Republic of Korea and the National

Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-

2014S1A5A2A01014933)

REFERENCES

Adams, DA., Nelson, RR, and Todd, PA. (1992)

Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of

information technology: a replication, MIS Quarterly,

6 (2), 227–247.

Aguinis H and Gottfredson RK (2010) Best-Practice

recommendations for estimating interaction effects

using moderated regression, Journal of Organizational

Behaviour, 31, 776 – 786.

Ajzen I and Fishbein M, Understanding Attitudes and

Predicting Social Behavior, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall,

Englewood Cliffs; 1980.

Babin BJ, Darden W and Griffin M, (1994) Work and/or

Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping

Value, Journal of Consumer Research, 644-656.

Barclay D, Thompson R and Higgins C, (1995) The

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal

Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption and Use an

Illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2): 285-309.

Bruner II GC and Kumar A, (2005) Explaining Consumer

Acceptance of Handled Internet devices, Journal of

Business Research, 58: 553-558.

Charlton JP and Danforth IDW, (2007) Distinguishing

addiction and high engagement in the context of online

UtilitarianValueandHedonicValueofMobileService-FocusingonMobileAddiction

625

game playing, Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3):

1531-1548.

Chin WW, The Partial Least Squares Approach to

Structural Equation Modeling. In: Marcoulides GA,

editor. Modern Methods for Business Research. NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahway; 1998. 295-336.

Chin WW, Marcolin BL and Newsted PR, (2003) A

partial least squares latent variable modeling approach

for measuring interaction effects: Results from a

Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic mail

adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2),

189–217.

Chiu HC, Hsieh YC, Li YC and Monle L, (2005)

Relationship Marketing and Consumer switching

behavior, Journal of Business Research, 58, 1681-

1689.

Cohen J., Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral

Sciences, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1988.

Compeau D.R., Higgins C.A. and Huff S., (1999) Social

cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing

technology: a longitudinal study, MIS Quarterly, 23

(2), 145 – 158.

Davis FD, Bagozzi RP and Warshaw PR, (1992) Extrinsic

and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the

workplace, Journal of Applied Social Psychology,

22(14), 1111–1132.

Davis FD, (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology,

MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Davis FD, Bagozzi RP and Warshaw PR, (1989) User

acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of

two theoretical models, Management Science, 35(8),

982-1003.

Davis RA, (2001) A cognitive-behavioral model of

pathological Internet use, Computers in Human

Behavior, 17, 187–195.

Deci E L, Intrinsic Motivation. New York: Plenum Press;

1975.

Fornell C and Bookstein FL, (1982) Two structural

equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to

consumer exit-voice theory, Journal of Marketing

Research, 19, 440–452.

Fornell C and Larcker, D F., (1981) Evaluating structural

equation models with unobservable variables and

measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, 18

(1), 39 – 50.

Goodhue D, Lewis W and Thompson R, (2003) Statistical

power in analyzing interaction effects: Questioning the

advantage of PLS with product indicators, Information

Systems Research, 18 (2), 211 – 227.

Igbaria M, Parasuraman S and Baroudi JJ, (1996) A

motivational model of microcomputer usage, Journal

of Management Information Systems, 13(1), 127-143.

Igbaria M, Schiffman SJ and Wieckowshi TS, (1994) The

respective roles of perceived usefulness and perceived

fun in the acceptance of microcomputer technology,

Behavior and Information Technology, 13(6), 349-

361.

Lohmoller JB, (1989) The PLS program system: Latent

variables path analysis with partial least squares

estimation, Multivariate Behavioral Research, 23(1),

125–127.

Li SM and Chung TM, (2006) Internet function and

Internet addictive behavior, Computers in Human

Behavior Forthcoming,.

Mathieson K, Peacock F and Chin WW, (2001) Extending

the technology acceptance model: The influence of

perceived user resources, Data Base Advanced

Information Systems, 32(3), 86 – 112.

Mendelson J and Nancy M, The Addictive Personality.

New York: Chelsea House; 1986.

O'Guinn TC and Faber RJ, (1989) Compulsive Buying: A

Phenomenological Exploration, Journal of Consumer

Research, 16, 147-157.

Okada EMJ, (2005) Justification Effects on Consumer

Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods, Journal of

Marketing Research, 42, 43–53.

Peter JL and Churchill GA, (1986) Relationships among

research design choices and psychometric properties

of rating scales: A meta-analysis, Journal of Marketing

Research, 23, 1 -10.

Sandelands LE, Asford SJ and Dutton JE, (1983)

Reconceptualizing the overjustification effect: a

template-matching approach, Motivation and Emotion,

7(3), 229-255.

Terel, O., Serenko, A. and Giles, P., (2011) Integrating

Technology Addiction and Use: An Empirical

Investigation of Online Auction Users, MIS Quarterly,

35 (4), 1043 – 1061.

Triandis HC, Attitude and Attitude Change. New York:

Wiley; 1971.

Venkatesh V, (2000) Determinants of Perceived Ease of

Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and

Emotion Into the Technology Acceptance Model,

Information Systems Research, 11(4), 342-365.

Voss KE, Spangenberg ER and Grohmann B, (2003)

Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of

Consumer Attitude, Journal of Marketing Research

2003, 40, 310–20.

WEBIST2015-11thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

626