Parameters Affecting the Energy Performance of the Transport

Sector in Smart Cities

M. Fernanda Mantilla R., Angelica Nieto L. and Jose L. Martinez Lastra

FAST-Lab, Tampere University of Technology (TUT), Tampere City, Finland

Keywords: Transport, Energy, Affecting Parameters, Mobility.

Abstract: The energy requirements of cities’ inhabitants have grown during the last decade. Recent studies justify the

necessity of reducing the energy consumption/emissions in cities. The present paper gives an overview of

the factors affecting the energy consumption of the citizens based on studies conducted in cities across the

globe. The studies cover all the factors that affect citizens’ mobility choice that at the end, affects in the

same way their final energy consumption. The results of the review are being used to support authorities in

mobility decisions in order to achieve a sustainable transport sector in smart cities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cities authorities have to face a constant growing

population in less space, which not only means

overcrowded systems but also a great demand of

energy. Additionally, it increases traffic jams, health

care problems, etc., resulting in a compromise

quality of life. Solutions to those problems include

integrated systems that use real time data to optimize

individuals’ mobility in a city scale without

compromise travellers’ destination.

It is relevant to understand the factors that

influence individual choice, so authorities can

modify citizens travel patterns. At the moment,

goverments have been changing infrastructures

capacity either by pricing roads or taking back fuel

subsides. However, authorities actions have a

limited impact if the affecting factors, like weather.

have a higher impact on citizen choice.

Currently, city authorities lack a tool to

determinate the future or current energy/emissions in

transport sector. In (Mantilla R. et al., n.d.) a

procedure for cities to measure the energy

performance of the transport sector has been

provided. However, it does not specify the

parameters that can be use to assest energy

efficiency evaluation. A set of performance indicatos

reported in (M. Fernanda Mantilla R. et al., n.d.) and

in the current document, will provide a metric for

authorities to judge the energy efficiency impact of

mobility projects.

This paper present the extensive literature review

that provides a initial stage for the development of

mobility projects, not only for authorities, but also

for all the sectors interested in inhabitants mobility

preferences or individual mobility choices. The

paper is organize as follows: section 2 gives an

overview of the affecting parameters. Section 3

presents the summary of idenfitied affecting

parameters. Section 4 sugest an application, and

section 5 present the conclusions and future work.

2 REVIEW OF PARAMETERS

AFFECTING ENERGY

CONSUMPTION/CARBON

FOOTPRINT VALUES

This section presents the parameters that affect the

Energy Consumption (EC)/Carbon Foot Print (CFP)

values. In the first place, environmental factors such

as a bad weather, may increase congestion, travelled

time, operational cost, or reduce PT reliability. In

this group of parameters, precipitations reduce

average speed on 5-40% with snow and 3-16% with

heavy raining (Leviäkangas et al., 2011). These

reductions leads to longer travel times, higher fuel

consumption, and higher EC from services such as

heating, air-conditioning and lighting (Considine,

2000; Guo et al., 2007).

Another environmental factor is the temperature,

83

Fernanda Mantilla R. M., Nieto L. A. and L. Martinez Lastra J..

Parameters Affecting the Energy Performance of the Transport Sector in Smart Cities.

DOI: 10.5220/0005489700830088

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS-2015), pages 83-88

ISBN: 978-989-758-105-2

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

(Guo et al., 2007) which has a correlation between

thermal sensitivity and drive travel demand. High

temperatures increase outdoor activities while on the

contrary low temperatures lead to decline them. In

the case where outdoors activities are in a walk or

cycling distance, the EC does not increase, however

countries like Finland, where the common vacations

are taking in cottages by 4 or 5 hours driving, results

in an increase of energy use and/or carbon

emissions.

Other system that is highly affected by the

weather is the PT. Several studies had shown that

buses are usually more sensitive to weather than

trams/trains, in addition, the trip purpose (work,

leisure, etc.) and time of the week (working days vs

weekend) increases or decreases that sensibility

(Considine, 2000; Guo et al., 2007; Winters et al.,

2007). Despite the weather influence over the

transport sector, the core in the emission levels/EC

depends on each of the people decisions on where to

go and how. In other words, “daily actions of

millions of individual actors. Reducing transports

environmental impact ... will... ultimately require a

more thorough understanding of how individuals

travel decision are motivated and/or constrained by

other factors” (Sitlington, 1999).

The following section describes some of the

variables that affect people’s transport choices.

Having in mind that those decisions are the heart of

the final EC, they represent a great potential for

reducing the overall consumption and/or emissions.

2.1 External Factors

2.1.1 Public Transport

Increases in the use of Public Transport (PT) can

increased by understanding the factors that

discourage its use, such as crowding, service

reliability, high prices, frequency, speed, lack of

information, and accessibility (Guo et al., 2007;

Sitlington, 1999; Paulley et al., 2006). High prices

decrease the PT use, contrary, low prices, increased

number of vehicles and their frequency raise PT

share. Factors with similar effect includes: high

population density, Gross domestic product (GDP)

per capital and the number of buses operating per

1000. G. Santos et.al. (2013) (Santos et al., 2013)

found that passenger’s characteristics such as age,

number of children and gender affects their modal

choice. Fuiji et al. (Fujii and Taniguchi, 2006)

concluded that the primary reason of the citizens for

not using PT is the negative image associated with it

(personal perception). In case of habitual car users,

they had a lack of knowledge about Alternative

Modes (ALM) or PT in terms of perception of time

control (travelled time). Extra facilities like

intermodal connection can change the public PT

perception, by promoting advantages of each of the

modes (Danish Ministry of Transport, 1996).

2.1.2 Cycling and Walking

Precipitation and temperature have strong influences

on cycling choice. Studies found that rain, wind and

temperature have independent effects. In (extremely)

low temperatures people commonly switch from

biking to car/PT, otherwise people walk or cycle,

especially with higher temperatures (>15). Heavy

snow reduces cycling by 60%, slippery surface by

20% and cold weather by 10% (Sabir et al., 2008;

Nankervis, 1999; Flynn et al., 2012). A way to

reduce the impact on biking is by bringing more

infrastructure support such as snow clearing and

sanding of ice along cycling routes, dedicated bike

lines and bike-friendly transit (Winters et al., 2007).

Other factors that increase bicycle use include

traffic-calmed streets, safe and dry and easy access

network, and facilities like parking and PT share

(Sitlington, 1999).

As an example, cities like Örebrö, Sweden has a

priority plan for snow removal and sanding of cycle

paths in the winter time and removal of sand in

spring. Oulu has same priority as well as Zaanstad in

the Netherlands (Heikkilä, 2013). Another example

is Copenhagen, where 80% of cyclists keep on going

in winter, where 90% of Copenhageners own a

bicycle (“Encourage Winter Cycling: Managing

mobility for a better future,” 2014).

Danish are a success story where bicycle is

perceive as a practical alternative for a safe and fast

travel. A survey found that Copenhagen cyclists ride

because: it is easy and fast (54%), for exercise

(19%) and only 1% for environmental reasons

(“Københavns Kommune: Borger,” n.d.). As a

conclusion, providing well usable infrastructure,

encouragement (incentives) and help with bicycle

maintenance can bring higher split percent’s of

cycling riding in cities.

2.1.3 Car Use

The use of private car is less efficient and high

energy demanding. The Environmental Protection

Agency determined that a drop in temperature from

24°C to 7°C increases fuel consumption in urban

trips from 12% to 28% (“US Environmental

Protection Agency,” n.d.; “Fuel Economy in Cold

Weather,” n.d.). This efficiency reduction is caused

SMARTGREENS2015-4thInternationalConferenceonSmartCitiesandGreenICTSystems

84

by several phenomena that happen inside the cars.

One of the causes is the time that takes for the

engine to reach its most fuel-efficient temperature,

warming up the vehicle before starting decreases the

efficiency as car is using fuel without moving.

Additionally, resources in comfort, such as heated

seats, window defrosters, and heater fans, requires

additional power (“Fuel Economy in Cold Weather,”

n.d.).

Authorities all over the globe are encouraging

users to switch to other modes through means of

promotion of energy efficient behaviour, including

energy efficient driving, car-pooling, car sharing,

and car-free zones/areas inside to cities (Danish

Ministry of Transport, 1996). But changes have to

break Travel Choice (TC) processes that are mainly

automatic, people only drive without considering

other alternatives and the cause of this is the

availability of a private vehicle, car ownership is the

principal determinant of car use (Sitlington, 1999;

Scheiner, 2010).

2.1.4 Infrastructure

Infrastructure refers to physical routes, buildings,

etc. that involve long-term capital investment and

determines the drive (car, bicycle etc.) conditions

during the whole year. Winter and spring are the

months for maintenance actions that influence

safety, accessibility, mobility and vehicle cost.

Winter maintenance operations represent a very

substantial portion of year-round maintenance costs

(Guo et al., 2007; Tyrinopoulos and Antoniou,

2013). In Canada $1,3 billion are used annually on

activities related with snow and ice control in public

roads (Leviäkangas et al., 2011). In Finland the cost

of maintenance during winter is 54% of the total

budget.

Additionally, the design of the infrastructure can

determinate the perception of the users. In the case

of PT, distance from start or destination point to

stops as well as the facilities during winter or

autumn (lights and shelter) can change travellers’

waiting and transfer experience. The greatest impact

of the infrastructure is in the mode choice. In

compact cities with high population density and low

available land, short trips are the main kind of trips

and use of PT, walking/cycling mode are the main

choices (Considine, 2000; Tyrinopoulos and

Antoniou, 2013; Scheiner and Holz-Rau, 2007).

2.1.5 Cost and Income

Relative cost of transport modes is an important

factor in TC. In the case of PT, the ticket price

usually reflects the cost of the system. Instead,

private car price is no clear, as it does not include all

their external cost, part of the unclearness comes

from the fact that most of that cost is subsidy for

local governments, representing 7.3% of the

European gross domestic product (Sitlington, 1999).

On the other hand, household income defines the

availability of private car. Results from Mobility

Management and housing program (2008) shows

that higher average income increases the number of

cars per house and their use by 34%. In comparison,

modal split with ALM and PT decreases in higher

proportion (de Jong and van de Riet, 2008;

Tyrinopoulos and Antoniou, 2013; Mobility

Management and housing, 2008).

2.1.6 Trip Characteristics

Some trip characteristics such as trip length, time

flexibility and trip purpose may affect the weather

impact on user’s TC. Long travel distances are more

sensitive to weather because of the exposure time.

Short trip times are less sensitive to weather

conditions. Important trip purpose (e.g. work) might

be more sensitive to weather than leisure ones (Guo

et al., 2007).

Trip length and time travelled are mainly defined

by infrastructure configurations. Basic facilities in

suburban areas such as the closest grocery, can

determinate the TC. If the perception of the distance

is high, car is generally accepted, in contrary, if the

distance is short, the use of bicycle or walk is

acceptable (Scheiner and Holz-Rau, 2007). M. Sabir

et.al. (2008) shows that an additional kilometre of

distance increases car use by 26,7% and PT with

2,2%, contrary to walking and cycling that decrease

by 23,1% and 7,4% respectively (Sabir et al., 2008)

Additionally, TC decisions are mainly done at home

and at work, so land design patterns between these

two destinations are crucial (Tyrinopoulos and

Antoniou, 2013; Mobility Management and housing,

2008; Frank et al., 2007).

2.1.7 Information

At the present time a considerable amount of

information is exchanged from transport system

consultation. Some of that information tried to

motivate car users to switch to PT by empowering

them with localised and advice information about

ALM/PT and leaving the choice to them

(Department of Transport, Australia, 2013). They

found that prioritized and effective distributed

information improves user’s perception (Sitlington,

1999; Department of Transport, Australia, 2013;

ParametersAffectingtheEnergyPerformanceoftheTransportSectorinSmartCities

85

Brög et al., 2002).

2.2 Personal Factors

Several factors can affect the travel behaviour of the

city inhabitants. On one side, personal factors can be

described as social-demographic characteristics,

such as gender, age, education or profession etc.;

and attitudinal factors like values, norms and

attitudes or perceptions about one specific mode.

2.2.1 Social-demographic Characteristics

Social-demographic characteristics, such as age,

gender, income etc., are the source of different

choices on similar conditions. By all means, a

teenager may view snow differently from an elderly

person. M. Sabir et al. (2008) found that age has a

great effect on TC, accordingly, older people (older

than 60) walk more than people younger than 18.

Similar studies in Canada have shown that older

adults and women with lower education and higher

income are much less likely to cycle than teenagers

and men (Winters et al., 2007). However countries

like Netherlands, where cycling is broadly-

entrenched with daily activities, the cycling rates do

not vary across gender or age (Sabir et al., 2008).

Other population that seems to get no affected by

weather conditions is the students. It is probably

cause by their limited transport options (cycling is

cheaper), combined with shorter distance.

Consequently, cities with high proportion of students

have higher cycling and walking rates (Santos et al.,

2013; Scheiner and Holz-Rau, 2007).

2.2.2 Motivations for Change

Initially, to generate some changes, it is required to

define and find the inhabitants habits. J. Prillwitz et

al. (2009) defined habits as an obstructive factor, as

they reduce conscious awareness. Habitual

behaviour simplifies and accelerates transport users’

actions and/or decisions, reducing perception of

travel alternatives, and increase cost for PT/ALM.

Both effects become more significant with an

increasing frequency of use of the TC. In this study

they found two ways to breakup habits, the first one

is by interrupted automatic actions and the second

one, by changing users’ contextual conditions

(Prillwitz and Barr, 2009).

One interrupting action is to introduce moral

considerations and at the same time ALM

information. Web sites such as bike Seasons not

only provide useful tips on how to drive a bicycle in

all seasons, but it is also used for creating cycling

groups. Similar interrupting action is by giving

information about their TC environmental impact,

especially in early ages. “Traffic snake game” in

some countries of Europe, aim to encourage schools,

children and parents to adopt ALM, car sharing or

PT when travelling to and from school (“Game |

Traffic Snake Game,”). In conclusion this kind of

actions break the traditional barriers associated with

ALM/PT like the additional effort and little comfort

perceptions (Prillwitz and Barr, 2009).

To summarize, psychological attachment to car,

lack of information and moral are factors that block

transport behavioural changes. A good quality of PT,

education and moral obligation reduce car use.

2.2.3 Critical Incidents

Another point of view is the critical incidents, where

the changes come from incidents like a crash car or

having a new car. P. van der Waerden et al. (2003)

identified two types of incidents: a change in the

number of available alternatives and a change in its

characteristics (Waerden et al., 2003).

Changes in the number of available alternatives

refer to events that modify the transport

composition. A limited number of studies had

research about life stages and their potential to break

travel habits (Prillwitz and Barr, 2009; Waerden et

al., 2003). Changes on the characteristics of

available alternatives make reference to

modifications in mode like time, cost, and comfort.

3 SUMMARY OF IDENTIFIED

PARAMETERS THAT AFFECT

THE ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN

THE TRANSPOR SECTOR

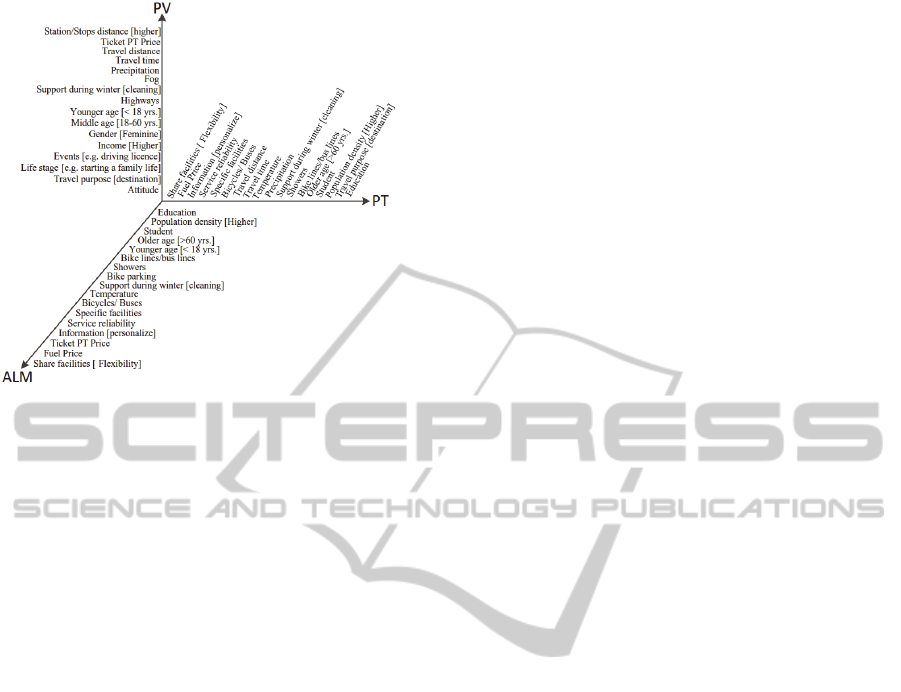

All the factors that were identified and described in

the previous section are summarized in Figure 1 the

position of the parameter represent a positive effect.

This list of parameters can be compared to the

outcomes of the energy efficiency of the transport

sector when they are under the effects of any (or

several) of them.

4 APPLICATIONS

Mobility authorities have found that, when solving

complex mobility problems, they can give

incentives, so people will figurate out what to do,

SMARTGREENS2015-4thInternationalConferenceonSmartCitiesandGreenICTSystems

86

Figure 1: Affecting Parameters: positive effect.

claiming that the system will organize itself. An

example from Stockholm showed reductions of cars

on 20%, in this specific case, the incentive were a

charge in bridges that connect downtown with

surrender neighbourhoods, meaning that somehow

the traffic flow organize itself (Eliasson and

Mattsson, 2006). The factors affecting transport

choices can be applied in a way that authorities can

give incentives in the case where the target mode

(PT or ALM etc.) is affected negatively by the

factors, before users make choices or penalize it in

situations where the factors are affecting positively

so the opportunity for change can be stablished.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Some affecting parameters were presented and

summarized in this paper. They are based on the

numerous studies and research in mobility. The

parameters are significant aspects related to the

energy performance of the smart cities, specifically

transport sector, which should be taken into account

when authorities implement mobility projects.

Therefore applications or services that use the

parameter can have a better approximation or

understanding the transport system performance.

Finally, future work will be in the application of

those parameters in smart cities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has partially received funding from

European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme

for research, technological development and

demonstration under grant agreement number

608885, correspondent to the project shortly entitled

MoveUs (ICT Cloud-Based Platform And Mobility

Services Available, Universal And Safe For All

Users).

REFERENCES

Brög, W., Erl, E., Mense, N., 2002. Individualised

marketing changing travel behaviour for a better

environment, in: Paper Presented at the OECD

Workshop: Environmentally Sustainable Transport.

pp. 06–12.

Considine, T.J., 2000. The impacts of weather variations

on energy demand and carbon emissions. Resour.

Energy Econ. 22, 295–314. doi:10.1016/S0928-

7655(00)00027-0.

Danish Ministry of Transport, 1996. The Danish

Government’s Action Plan for Reduction of the CO2-

Emissions of Transport Sector.

De Jong, G.C., van de Riet, O., 2008. The driving factors

of passenger transport. EJTIR 3.

Department of Transport, Australia, 2013. TravelSmart /

Living Smart (WWW Document). URL

http://www.transport.wa.gov.au/activetransport/24605.

asp (accessed 8.21.14).

Eliasson, J., Mattsson, L.-G., 2006. Equity effects of

congestion pricing: Quantitative methodology and a

case study for Stockholm. Transp. Res. Part Policy

Pract. 40, 602–620. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2005.11.002.

Encourage Winter Cycling: Managing mobility for a

better future (WWW Document), 2014.EPOMM Eur.

Platf. Mobil. Manag. URL http://www.civitas.eu/sites/

default/files/epomm_eupdate_en_winter_cyling .pdf

(accessed 8.13.14).

Flynn, B.S ., Dana, G.S., Sears, J., Aultman-Hall, L.,

2012. Weather Factor Impacts on Commuting to Work

by Bicycle (No. 12-006). Transportation Research

Center Farrell Hall, Burlington.

Frank, L., Bradley, M., Kavage, S., Chapman, J., Lawton,

T.K., 2007. Urban form, travel time, and cost

relationships with tour complexity and mode choice.

Transportation 35, 37–54. doi:10.1007/s11116-007-

9136-6.

Fuel Economy in Cold Weather (WWW Document), n.d.

URL http://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/

coldweather.shtml (accessed 8.13.14).

Fujii, S., Taniguchi, A., 2006. Determinants of the

effectiveness of travel feedback programs—a review

of communicative mobility management measures for

changing travel behaviour in Japan. Transp. Policy 13,

339–348. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2005.12.007.

Game | Traffic Snake Game (WWW Document), n.d. URL

http://www.trafficsnakegame.eu/game/ (accessed

2.11.15).

Guo, Z., Wilson, N.H.M., Rahbee, A., 2007. The impact

ParametersAffectingtheEnergyPerformanceoftheTransportSectorinSmartCities

87

of weather on transit ridership in Chicago. Presented at

the TRB 2007 Annual Meeting, Massachusetts.

Heikkilä, P., 2013. winter cycling in Oulu- towards new

challenges. Presented at the Winter Cycling Congress,

Oulu, Finland.

Københavns Kommune: Borger (WWW Document), n.d.

URL http://www.kk.dk/da/borger (accessed 8.18.14).

Leviäkangas, P., Tuominen, A., Molarius, R., Kojo, H.,

Schabel, J., Toivonen, S., Keränen, J., Ludvigsen, J.,

Vajda, A., Tuomenvirta, H., Juga, I., Nurmi, P.,

Rauhala, J., Rehm, F., Gerz, T., Muehlhausen, T.,

Schweighofer, J., Michaelides, S., Papadakis, M.,

Dotzek, N., Groenemeijer, P., 2011. Extreme weather

impacts on transport systems.

Mantilla R., M.F., Nieto L., A., Martinez Lastra, J.L.,

Kotakorpi, E., n.d. Methodology for energy efficiency

assessment in the transport sector for smart cities.

Unpublished.

M. Fernanda Mantilla R., Nieto L., A., Martinez Lastra,

J.L., n.d. Definition of Key Performance Indicators

for Energy Efficient Assessment in the Transport

Sector. (Unpublished).

Mobility Management and housing, 2008. Factors

Influence Mobility Behaviour.

Nankervis, M., 1999. The effect of weather and climate on

bicycle commuting. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 33,

417–431.

Paulley, N., Balcombe, R., Mackett, R., Titheridge, H.,

Preston, J., Wardman, M., Shires, J., White, P., 2006.

The demand for public transport: The effects of fares,

quality of service, income and car ownership. Transp.

Policy 13, 295–306.

Prillwitz, J., Barr, S., 2009. Motivations and barriers to

adopting sustainable travel behaviour.

Sabir, M., Koetse, M.J., Rietveld, P., 2008. The impact of

weather conditions on mode choice: empirical

evidence for the Netherlands. Dep. Spat. Econ. VU

Univ. Amst.

Santos, G., Maoh, H., Potoglou, D., von Brunn, T., 2013.

Factors influencing modal split of commuting

journeys in medium-size European cities. J. Transp.

Geogr. 30, 127–137. doi:10.1016/

j.jtrangeo.2013.04.005.

Scheiner, J., 2010. Interrelations between travel mode

choice and trip distance: trends in Germany 1976–

2002. J. Transp. Geogr. 18, 75–84.

doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.01.001.

Scheiner, J., Holz-Rau, C., 2007. Travel mode choice:

affected by objective or subjective determinants?

Transportation 34, 487–511.

Sitlington, J., 1999. Moving to Healthier people and

Healthier Places. VicHealth, health promotion

foundation, Autralia.

Tyrinopoulos, Y., Antoniou, C., 2013. Factors affecting

modal choice in urban mobility. Eur. Transp. Res.

Rev. 5, 27–39. doi:10.1007/s12544-012-0088-3.

US Environmental Protection Agency (WWW Document),

n.d. URL http://www.epa.gov/ (accessed 8.18.14).

Waerden, P. van der, Timmermans, H., Borgers, A., 2003.

Key Events and Critical Incidents Influencing

Transport Mode Choice Switching Behavior: A

descriptive analysis, in: The Physical and Social

Dimensions of Travel. Presented at the 10 the

International Conference on Travel Behaviour

Research, Lucerne.

Winters, M., Friesen, M.C., Koehoorn, M., Teschke, K.,

2007. Utilitarian Bicycling: A Multilevel Analysis of

Climate and Personal Influences. Am. J. Prev. Med.

32, 52–58. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.027.

SMARTGREENS2015-4thInternationalConferenceonSmartCitiesandGreenICTSystems

88