Layered Knowledge Networking in Professional Learning

Environments

Mohamed Amine Chatti, Hendrik Thüs, Christoph Greven and Ulrik Schroeder

Informatik 9 (Learning Technologies) RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Technology Enhanced Learning, Lifelong Learning, Professional Learning,

Work-Integrated Learning, Personalized Learning, Network Learning.

Abstract: Knowledge Management (KM) and Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) became a very important issue

in modern organizational professional learning and work process integration. Former learning and KM

theories which characterize knowledge as a thing or process no longer fit today's digital world where the

amount of required information is no more manageable and the half-time of knowledge in general is rapidly

decreasing. Younger approaches such as the Learning as a Network (LaaN) theory describe knowledge as

complex and emergent and put a heavier focus on knowledge networking. The LaaN theory further stresses

the convergence of the learning and work processes in professional learning settings and views KM and

TEL as two sides of the same coin. Driven by the LaaN theory, the Professional Reflective Mobile Personal

Learning Environments (PRiME) project describes an integrated KM and TEL framework which connects

learning and work processes. It enables the professional learner to harness implicit knowledge and offers

knowledge networking at three different layers: the Personal Learning Environment (PLE), the Personal

Knowledge Network (PKN) and the Network of Practice (NoP). Continuous knowledge networking results

in constant evolution of knowledge leading to personal as well as organizational learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since its introduction in the early 1990s, Knowledge

Management (KM) has always played an important

role to increase the productivity of knowledge

workers and achieve organizational benefits. Mainly

following two major approaches regarding

knowledge-as-a-thing on the one hand or

knowledge-as-a-process on the other hand, KM

could not fulfill the high hopes laid in it. Also, the

finding that knowledge is something personal in

nature could not help out when Personal Knowledge

Management (PKM) came up in the past couple of

years (Chatti, 2012).

Similarly, over the last decade, Technology-

Enhanced Learning (TEL) has been addressed as a

possibility to go new ways in education, but as with

KM the view of learning as a passive, teacher-driven

process where knowledge is viewed as an object that

can be transferred from the mind of the teacher to

the mind of the students precluded a real innovative

success. That did not change with the emergence of

the Web 2.0 movement which brought up various

tools to connect learners and put them in an active

role. The traditional pedagogical principles were,

however, kept untouched.

In a professional context, despite the recognition

of the strong links between KM and TEL, the two

fields are still evolving down separate paths. In this

paper, we recapitulate the shortfalls of KM and TEL

and present the Learning as a Network (LaaN)

theory as a new vision of learning defined by the

convergence of KM and TEL concepts into one

solution. Furthermore, we present a possible

application of the LaaN theory in the frame of the

Professional Reflective Personal Mobile Learning

Environments (PRiME) Project. PRiME focuses on

the convergence of the learning and working

processes and proposes an integrated KM and TEL

framework that offers layered knowledge

networking to foster continuous individual and

organizational learning

The remainder of this paper is structured as

follows. Section 2 addresses the relationship

between professional learning and knowledge

management. In Section 3, we briefly discuss the

LaaN theory as a theoretical basis for our work.

Section 4 presents the conceptual and

implementation details of the PRiME project.

363

Chatti M., Thüs H., Greven C. and Schroeder U..

Layered Knowledge Networking in Professional Learning Environments.

DOI: 10.5220/0005491803630371

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 363-371

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Finally, Section 5 gives a summary of the main

results of the paper and outlines perspectives for

future work.

2 KM AND TEL

In a company context, Knowledge Management

(KM) and Technology-Enhanced Learning (TEL)

have so far been regarded as two impartial areas.

While KM concentrates on knowledge creation and

distribution, TEL focuses on formal learning and

training of the employees. This tightened perspective

can still be read from today’s companies’ structures.

KM and TEL are commonly related to two different

departments, namely IT and human resources.

2.1 KM

With the emergence of KM in the 1990s,

organizations had highest hopes in it to improve the

knowledge worker performance and at the same time

increase the efficiency of the organization to achieve

strategic advantages. In the KM literature, there have

been two major views on knowledge, namely

knowledge-as-a-thing and knowledge-as-a-process

(Chatti, 2012; Chatti et al., 2012).

The idea of knowledge-as-a-thing assumes KM

to be most likely simple information management

(Hildreth and Kimble, 2002; Kimble et al., 2001;

Malhotra, 2005; Wilson, 2002). In general, it covers

information capturing, storing, and reusing.

Capturing knowledge, however, is not an easy task

and moreover very time and effort consuming. The

management of knowledge also conflicts with the

work process and describes an additional overload.

Furthermore, the knowledge-as-a-thing KM models

cannot deal with the complex nature of knowledge

including e.g. knowledge evolution or its context-

sensitivity.

The more recent KM initiatives stress the

importance of the people’s side of KM and view

knowledge as a process. These initiatives often

address the duality of knowledge and move the

focus to the distinction and conversion between tacit

and explicit knowledge. A popular representative of

the class of knowledge-as-a-process KM models is

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s SECI model, which

describes knowledge as a spiraling process of

socialization, externalization, combination, and

internalization which are transforming knowledge

between tacit and explicit forms (Nonaka and

Takeuchi, 1995). Due to the variable iterations of the

four steps, the model creates the impression to be

flexible. However, it is as predetermined as all the

knowledge-as-a-process KM models trying to

describe an automated process for knowledge

creation not able to deal with complexity of

knowledge and the unpredictable nature of the KM

process.

In response, in recent years, the importance of

personal knowledge has been highlighted in various

works and the interest in the topic of personal

knowledge management (PKM) has steadily

increased (Gorman and Pauleen, 2011; Jarche, 2010;

Prusak and Cranefield, 2011; Snowden et al., 2011).

PKM recognizes that knowledge as well as learning

is personal in nature. It puts the knowledge worker

and her tacit knowledge at the center. In contrast to

the early KM approaches, the PKM approach shows

a bottom-up instead of top-down flow of knowledge.

However, the current PKM approaches are still very

process-oriented and do not really deal with the

relation between personal and organizational KM.

So far, there are no underlying, supporting

theoretical frameworks for PKM and problems like

rapidly changing knowledge with a very short half-

life, the complexity of work and its environments,

etc. are not considered (Chatti, 2012).

2.2 TEL

TEL actually shares the same fate with KM.

Summarizing different available approaches, TEL

commonly means offering Virtual Learning

Environments (VLE). These include Learning

Management Systems, Learning Content

Management Systems, Content Management

Systems, and Course Management Systems. All of

them concentrate on the provision of information.

Although efforts have been made in regard to

interoperability of such information repositories,

they are still centralized and commonly under the

control of a formal educational institution (Downes,

2005).

In the last years, TEL has been influenced by the

emergence of the Web 2.0 movement. The term TEL

2.0 emerged to refer to TEL approaches that adapt

new techniques for collaboration, networking, and

learners’ active participation in the learning process.

While that offers great possibilities, TEL did not

really change or influence the traditional

pedagogical principles behind it. Content is still

organized in standard ways, following the top-down

approach pushing information to the learners.

Gained knowledge is time-limited e.g. semester-

bound and not seen as continuous or fluid. By this

linear and predefined process, newly gained

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

364

knowledge cannot be reused and gets lost (Brown

and Adler, 2008; Mott and Wiley, 2009).

2.3 Convergence of KM and TEL

Over the past years, companies and researchers are

starting to recognize relationships and intersections

between the KM and TEL fields and to explore the

potential and benefits of their integration (Grace and

Butler, 2005; Lytras et al., 2005; Malhotra, 2005).

Chatti et al. (2012) go a step further and point out

that professional learning and knowledge

management can be viewed as two sides of the same

coin and stress the need for the seamless integration

of the two concepts into one solution for the purpose

of increasing individual and organizational

performance. The authors introduce the Learning as

a Network (LaaN) theory as a bridge between TEL

and KM. In the next section, we briefly discuss the

LaaN theory as a theoretical basis for our work.

3 THE LAAN THEORY

The Learning as a Network (LaaN) theory has been

proposed by Chatti (2010a, 2010b) as a new vision

of learning towards a new model of personalized and

networked learning. LaaN provides the theoretical

foundation to address the diverse learning needs of

individual learners in today’s learning environments

characterized by increasing complexity and fast-

paced change. LaaN draws together some of the

concepts behind connectivism (Siemens, 2005),

complexity theory (Holland, 1992, 1998; Snowden,

2002), and double-loop learning (Argyris & Schön,

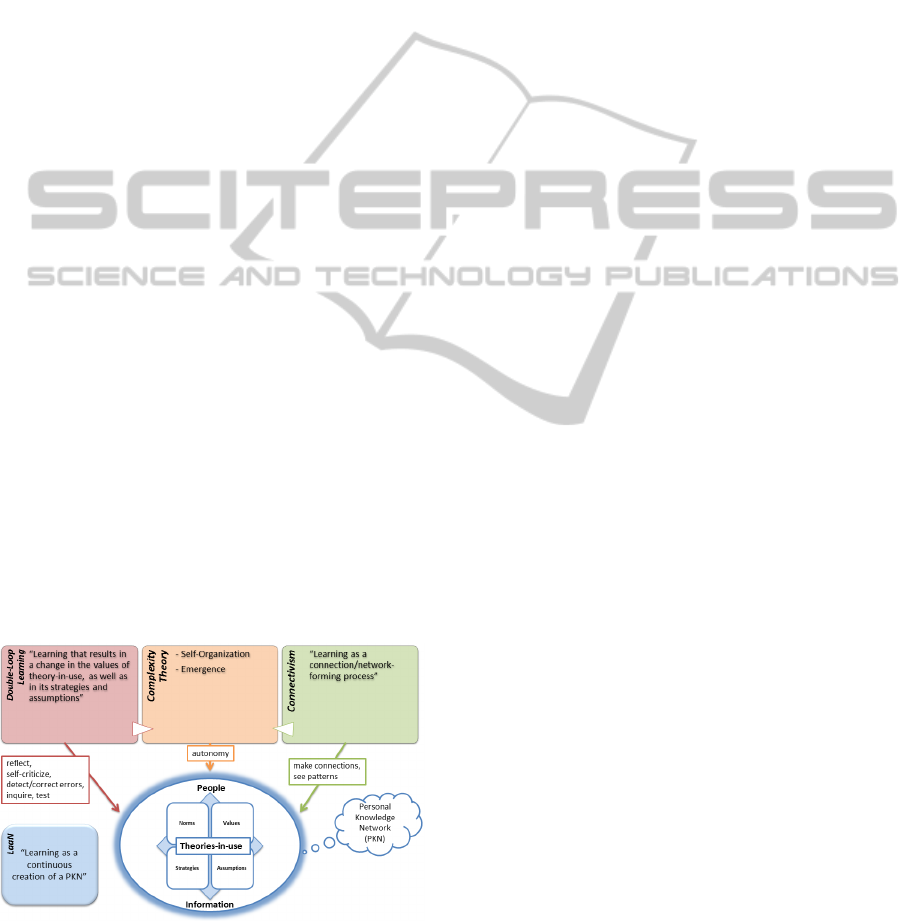

1978, 1996). An abstract view of LaaN is depicted in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: The LaaN Theory (Chatti, 2010a).

Within LaaN, connectivism, complexity theory, and

double-loop learning converge around a learner-

centric environment. LaaN starts from the learner

and views learning as the continuous creation of a

Personal Knowledge Network (PKN). A PKN

shapes the knowledge home and the identity of the

individual learner. For each learner, a PKN is a

unique adaptive repertoire of:

• Tacit and explicit knowledge nodes (i.e.,

people and information) (external level).

• One’s theories-in-use. This includes norms for

individual performance, strategies for

achieving values, and assumptions that bind

strategies and values together

(conceptual/internal level).

In LaaN, the result of learning is a restructuring

of one’s PKN, that is, an extension of one’s external

network with new knowledge nodes (external level)

and a reframing of one’s theories-in-use

(conceptual/internal level).

LaaN-based learning implies that a learner needs

to be a good knowledge networker as well as a good

double-loop learner. The ability to create an own

representation of knowledge, reflect, (self-) criticize

and finally change and correct it is as important as

the capability to recognize patterns or find,

aggregate, and remix available knowledge nodes.

At the heart of LaaN lie knowledge ecologies. A

knowledge ecology is based on the concept of

PKNs, loosely joined, and can be defined as a

complex, knowledge intensive landscape that

emerges from the bottom-up connection of PKNs.

Knowledge ecologies house self-directed learning

that occurs in a bottom-up and emergent manner,

rather than learning that functions within a

structured context of an overarching framework,

shaped by command and control. As compared to

popular social forms that have been introduced in

the CSCL and CSCW literature such as communities

of practice, knots, coalitions, and intensional

networks, knowledge ecologies are more open, more

flexible, less predictable, and less controlled (Chatti

et al., 2012).

LaaN further represents a vision of professional

learning, where the line between KM and TEL

disappears. Unlike traditional KM and TEL

perspectives, LaaN views knowledge as a personal

network rather than as a thing or process. In LaaN,

work/learning is viewed from a professional learner

perspective, and KM and TEL are seen as being

primarily concerned with a continuous creation of a

PKN. This ensures that the differences between KM

and TEL are converging around a learner-centric

work/learning environment and manage that the

roles of KM and TEL are blurring into one, namely

supporting professional learners in continuously

LayeredKnowledgeNetworkinginProfessionalLearningEnvironments

365

creating and optimizing their PKNs. In this sense,

KM and TEL are not the two ends of a continuum

but the two sides of the same coin. Moreover, LaaN

enables the seamless integration of learning and

work. The view of learning as the continuous

creation of a PKN makes learning and work so

intertwined that learning becomes work and work

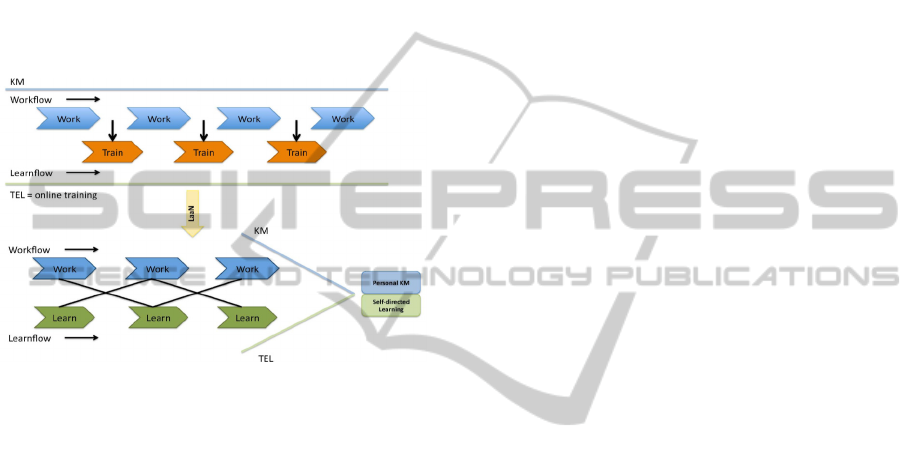

becomes learning. As illustrated in Figure 2,

professional learning in LaaN is no longer regarded

as an external online training activity separate from

the work flow, but rather as a learner-controlled

evolving activity embedded directly into work

processes (Chatti et al., 2012).

Figure 2: LaaN: Convergence of KM and TEL (Chatti et

al., 2012).

In the next section, we present the details of the

PRiME project as a possible application of the LaaN

theory.

4 PRIME

The joint research project Professional Reflective

Mobile Personal Learning Environments (PRiME) is

conducted by the Learning Technologies Research

Group of the RWTH Aachen University and DB

Training, Learning & Consulting of the Deutsche

Bahn AG. It is funded by the German Federal

Ministry of Education and Research with a runtime

of three years, finishing in June 2016 (Greven et al.,

2014).

PRiME illustrates the LaaN theory in action. It

offers an integrated professional learning and

knowledge management framework for personal as

well as organizational learning, addressing the

following objectives:

• Provide an innovative professional learning

approach, where informal and network learning

converge around a self-directed learning

environment.

• Design a work-integrated framework that links

mobile job activities and self-directed learning

in context.

• Develop and evaluate mobile learning

applications to support mobile learning in

context.

• Support continuous knowledge networking and

reflection at three levels: (a) the personal

learning environment (PLE) level where

professional learners can annotate learning

materials on their mobile tablet devices; (b)

these materials can be shared, commented, and

rated by peers at the personal knowledge

network (PKN) level; (c) the newly generated

learning materials can then be shared and used

within the company at the network of practice

(NoP) level.

• Develop and evaluate learning analytics tools

and methods (e.g. dashboards,

recommendation, intelligent feedback, context-

based search) to support reflective learning at

the workplace.

In the next sections, we discuss the underlying

concepts and the current implementation results of

the PRiME project.

4.1 Conceptual Approach

The main goal of PRiME is to offer seamless

learning across time, location, and social contexts

combining the work and learning processes into one.

Context has been identified as a key factor in

workplace learning to achieve effective learning

activities. Nowadays, professional learners perform

in highly complex knowledge environments. They

have to deal with a wide range of activities they

have to manage every day. Moreover, they have to

combine learning activities and their private and

professional daily life. The challenge here is thus

how to support learning activities across different

contexts (Greven et al., 2014, Thüs et al., 2012).

PRiME translates the principles of LaaN into

actual practice. In PRiME, a professional learner is a

lifelong learner who is continuously creating and

optimizing her network. Driven by LaaN principles,

PRiME aims at helping professional learners to

continuously build their personal networks in an

effective and efficient way, by providing a freeform

and emergent environment conducive to networking,

inquiry, and trial-and-error; that is an open

environment in which learners can make

connections, see patterns, reflect, (self)-criticize,

detect and correct errors, inquire, test, challenge and

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

366

eventually change their knowledge; thus changing

the organizational knowledge.

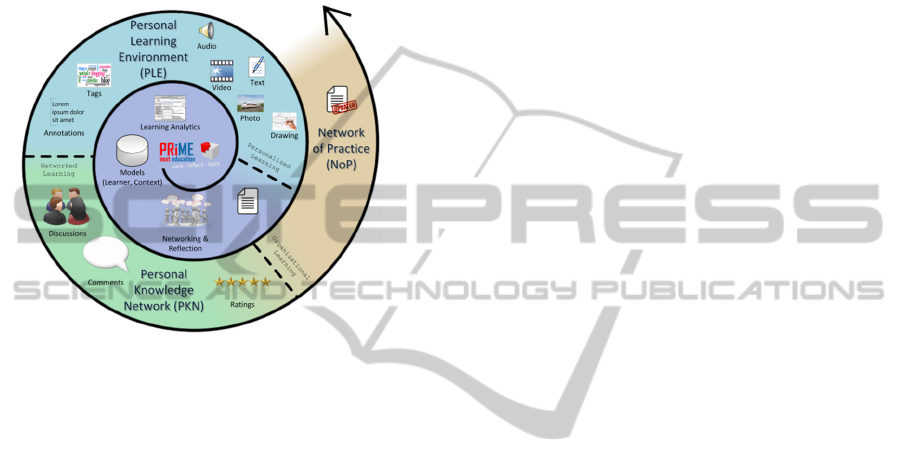

The learning process in PRiME is a spiral and

cyclic conversion of individual and organizational

knowledge at three different layers of knowledge

networking and maturity: the personal learning

environment (PLE), the personal knowledge

network (PKN), and the network of practice (NoP),

as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Continuous Knowledge Networking in PRiME.

4.2 Implementation

PRiME provides an integrated learning and work

platform through a set of Web and mobile

applications to support continuous knowledge

networking at the three different layers. The

platform can be used in any organizational setting.

Mobile professional learners represent the primary

target group of PRiME. As a proof of concept, we

addressed in this work service technicians at

Deutsche Bahn as a possible target group. These

include car inspectors, specialist authors, training

developers, and trainers working in the field of car

inspection service. The car inspector is a mechanic

that performs rail-worthiness checks on trains. He

repairs small-scale damages on trains and decides

about trains’ dispositions on extensive problems.

The specialist author is responsible for the creation

of new learning resources. The training developers

are responsible for the selection, aggregation, and

creation of trainings from existing learning materials

created by specialist authors. The trainers are

responsible for the organization and execution of the

professional technical trainings and workshops with

car inspectors. They use the learning materials

prepared by training developers.

The document base in the PRiME platform

consists of existing company documents, such as

guidelines and instruction rules. The majority of

such documents are already available in a digital

form, e.g. as Word, PowerPoint or PDF. Through a

Web-based application, called the Bundler (see

Figure 1), these documents are imported into the

PRiME system, processed according to their

hierarchical logical structure, and stored in a tree-

like structure. Specialist authors can use the Bundler

to upload their documents, which can be

automatically processed to fit the PRiME data

schema which consists of so-called Snippets and

Bundles. Snippets represent atomic learning units

that can take the form of text, table, image, audio, or

video. Bundles are used to structure such snippets.

Each bundle can hold several snippets and also

several sub-bundles. The bundles can be seen as the

structure of sections in a book, whereas the snippets

are the content of a book. Whenever possible,

additional information, such as the name of the

author, keywords, or other metadata, is also

extracted from the uploaded document. After this

initial step, the document is presented in its tree-like

structure of bundles and snippets to the specialist

author who can manually alter the automatically

generated result by splitting and merging single

elements. When the author is satisfied with the

result, the initial version of this document is released

to the PRiME system as a set of bundles and

snippets which can be used by car inspectors as

learning resources and reused by training developers

and trainers as building blocks for training and

workshop materials.

The Bundler can further be used by training

developers to mash up and create own bundles from

existing bundles and snippets in the PRiME system

according to their needs (see Figure 4). Thereby, the

training developers can search for already existing

snippets. Different filters and search criteria help to

limit the search results to only show context-relevant

snippets. In the left column of the screenshot, a tree-

like view helps to easily structure and arrange

snippets at various levels of a new bundle with

simple drag and drop actions. The right column

shows a document-like view of the aggregated

bundle. The new bundle is then published and can be

used by trainers in their workshops and subscribed

to by the car inspectors who are interested in it. The

Bundler further offers different export modules that

allow the trainer to convert bundles to traditional

formats, such as pdf, word, PowerPoint that can be

used as handouts in the workshop.

In addition to converting an existing document to

snippets, and mixing up existing snippets to new

bundles, the specialist author may also use the

LayeredKnowledgeNetworkinginProfessionalLearningEnvironments

367

Bundler application to create snippets and bundles

from scratch.

Figure 4: Bundler: Existing documents are imported and

processed in the PRiME system.

In PRiME, learning is a continuous process

which involves the learners, their personal networks,

and the organization itself. PRiME divides the

learning and working process into three layers,

namely the Personal Learning Environment (PLE),

the Personal Knowledge Network (PKN), and the

Network of Practice (NoP). In the following

sections, we discuss in detail the work and learning

activities in relation to each layer and how these

activities are supported by the PRiME tool set.

4.2.1 Personal Learning Environment (PLE)

A Personal Learning Environment (PLE) enables

professional learners to compile their own individual

knowledge assets which are relevant for their

everyday working context. Each learner decides on

her own, which information is important for solving

daily tasks and for improving one’s knowledge. The

task of a mobile PLE is to support the learners in

their everyday life, either for solving current tasks

and problems or for learning in context. Knowledge

assets in the PRiME system include bundles,

snippets, and annotations. An annotation is

multimedia information created by the learner,

which can either be attached to bundles and snippets

or detached from those structures.

In a PLE, a learner should not only be able to

define which information is available but also how

the learning environment should look like. One

possibility to achieve this is to implement one

monolithic application with all the required

functionalities and various options for the learner to

adjust everything. In the PRiME system, we opted

for a set of applications where each application is

responsible for a single task. All PRiME

applications are able to communicate with each

other and to share functionalities. By selecting the

own set of applications, the learner also decides how

the own learning environment looks like. The

starting point for all the PRiME applications on the

learner’s mobile device is the Dashboard (see

Figure 5). It encapsulates all the functionalities by

displaying each PRiME application and by

providing a centralized communication system for

all the installed applications in the PRiME

ecosystem.

Figure 5: The Dashboard is the main entry point to the

PRiME ecosystem.

With the help of the application BundleReader

(see Figure 6), a car inspector is able to subscribe to,

create, and display her own set of bundles and

snippets that are required for her work. Alongside,

she can also create her own multimedia annotation

for each bundle or snippet available in the

application. For displaying additional information

for one bundle or snippet, the user has to swipe a bar

from the right border to the center. This newly

opened area contains all the metadata about the

currently highlighted bundle or snippet, namely the

author, the version, the date of last change, as well

as public annotations and comments. Annotations

are questions and corrections to a bundle or snippet

that offer the possibility to capture knowledge

during the work process. Instead of taking a note on

a loose sheet of paper which normally gets lost, car

inspectors can take a photo of a machine or record a

short video of a procedure. In general, annotations

cover various types of multimedia (e.g. text, image,

audio, video, or drawing) which can be created very

easy and they provide a great expressiveness at the

same time. To create a new personal annotation, a

user can just tap the toolbox in the upper right corner

and select the type of annotation to be added. The

newly created annotation will appear on the right

side of the application, associated with the bundle or

snippet it has been created for. Annotations are

context-sensitive and can be extended automatically

with meta-information, such as recording time or

location. At first, they are strictly personal and not

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

368

visible to any other user. Thus, they can hold some

personal work instructions that are helpful for future

tasks. Furthermore, the car inspector can use the

intelligent search functionality provided by the

BundleReader to discover context-relevant bundles.

For example, some knowledge is location-based due

to machinery, or physical conditions such as noise

might result in exclusion of media types containing

audio. The search result can further be filtered

according to author, topic, keywords, time, location,

etc.

Figure 6: The BundleReader enables learners to subscribe

to, display and annotate bundles and snippets.

Car inspectors at work often do not have the time

to write extensive annotations and link them to a

specific bundle or snippet. The application Notepad

was developed to support car inspectors in taking

quick notes in form of text, picture, video, audio, or

drawing which can be used for self-reflection after

work or as basis for annotations on bundles and

snippets in the BundleReader. For example, while

reading a snippet, the car inspector might remember

that she took a picture which can clarify the

instructions given in the snippet and use the picture

as annotation for that snippet.

Figure 7 shows the Notepad application. A new

note can easily be created by tapping the red button

in the lower right side of the application. A new

menu appears where the car inspector can select

which kind of note she wants to create. In addition to

the note itself, keywords, short comments and other

meta information, such as time and location can be

added optionally. This simplifies the process of

finding the correct note when needed. Selection

from storage like SD card is possible as well as

using the device-internal tools to record multimedia

like the camera application. A personal media

gallery collects all the created notes. The car

inspector can define when to synchronize them with

a server-side personal repository.

Figure 7: The Notepad enables learners to quickly take

notes in their PLE.

4.2.2 Personal Knowledge Network (PKN)

The Personal Knowledge Network (PKN) layer

fosters continuous networking and collaborative

knowledge creation. It enables professional learners

to share tips and tricks and collaboratively work on

the constant improvement of the available

knowledge assets.

As mentioned in the previous section, at the PLE

layer, a car inspector can use the BundleReader to

make annotations on the bundles and snippets she

has subscribed to and keep them private per default.

If she decides that her personal annotations are

worth sharing, she can publish them to all other

subscribers or share them with selected peers or

groups that can be personally defined. Annotations

can then be seen by all recipients who can give

ratings and might reply to these annotations with

their own ones. This way, expert discussions can

emerge resulting in collaborative creation and

maturing of knowledge. Car inspectors who apply

the knowledge in their daily tasks have thus the

possibility to give valuable feedback to aid the

specialist authors in improving the produced bundles

and snippets.

As the available knowledge is rapidly growing

and updates in the system are hard to track, PRiME

users should have an easy way to stay up to date

without being overwhelmed with the constant flow

of information. This is achieved through the native

mobile application Newsstream which provides an

aggregated view of recent activities in the PRiME

system, as shown in Figure 8. Car inspectors,

specialist authors, training developers, and trainers

who subscribed to a specific bundle continuously

receive notifications on the annotations, ratings, and

changes made to the bundle. By clicking on a

notification, they are directly forwarded to the

respective bundle, snippet, or annotation in the

BundleReader. Car inspectors can follow the

discussion and rating activities on the bundle or

LayeredKnowledgeNetworkinginProfessionalLearningEnvironments

369

snippet they are interested in and discover quality

annotations contributed by peers. They can also set

filters so that e.g. only notifications related to a

specific snippet or given by a specific peer are

displayed. Furthermore, they can use the

Newsstream to receive recommendations according

to their preferences and activities in the system. On

the other hand, specialist authors, training

developers, and trainers can get continuous feedback

that can be used in the enhancement of their snippets

and bundles.

Figure 8: The Newsreader provides an aggregated view of

recent activities.

4.2.3 Network of Practice (NoP)

The Network of Practice (NoP) represents the

organization layer in PRiME. It supports the

propagation of the knowledge created at the PLE

and PKN layers to the entire organization. The NoP

layer harnesses the collective intelligence to ensure

that the organizational knowledge is accurate and up

to date. An organization represents a knowledge

ecology. Organizational learning occurs when

individuals within an organization experience a

problem and work on solving this problem. This

happens through a continuous process of

organizational inquiry, where everyone in the

organizational environment can inquire, test,

compare and adjust her knowledge, which is a

private image of the organizational knowledge.

Effective organizational inquiry then leads to an

update of one’s knowledge, thereby updating the

organizational knowledge.

The knowledge which is available in PRiME can

be continuously improved with every action in the

system. At the PKN layer, the collective intelligence

decides which knowledge is of high quality through

commenting and rating. Quality knowledge that

emerges as a result of the continuous interaction

between PRiME users at the PKN layer builds the

cornerstone for the enhancement of the organization-

wide knowledge assets. When a new annotation to a

snippet at the PKN layer is highly rated, the

specialist author is notified and can use this

annotation for the enhancement of the snippet.

Training developers and trainers can use the

improved snippet in their trainings and workshops.

Car inspectors who subscribed to this snippet will

automatically get notified about this update. The

whole process starts then anew at the PLE layer.

This continuous knowledge networking process

ensures an effective individual and organizational

learning.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) in

professional and organizational settings is

increasingly gaining importance. In this paper, we

addressed the challenge of convergence of

professional learning and knowledge management

(KM). Driven by the learning as a network (LaaN)

theory, which presents a new perspective

characterized by the convergence of learning and

work within a learner-centric knowledge

environment, we discussed the conceptual and

implementation details of the Professional Reflective

Mobile Personal Learning Environments (PRiME)

project. PRiME fosters knowledge in action and

provides a new vision of learning at the workplace

defined by the seamless integration of TEL and KM

concepts into one solution toward a new model of

professional learning in context. Learning in PRiME

is the result of continuous knowledge networking at

three layers, namely personal learning environment

(PLE), personal knowledge network (PKN), and

network of practice (NoP). Different mobile

applications have been introduced to support the

various activities related to each of these layers.

We had a series of workshops with potential

PRiME users at Deutsche Bahn in which we

collected requirements and discussed early

prototypes of the different applications. We plan to

perform an empirical study of our approach, which

will allow us to thoroughly evaluate the usability of

the developed applications as well as the

effectiveness of our method to support work-

integrated networked learning. Besides extending

the PRiME application ecosystem, future work will

also include the implementation of personal

dashboards to support self-reflection and awareness,

as well as different learning analytics methods that

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

370

leverages the context information to provide

effective recommendation and intelligent feedback

to PRiME users.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C., Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational

Learning, A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading,

Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Argyris, C., Schön, D. A. (1996). Organizational Learning

II: Theory, Method and Practice. Reading,

Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Brown, J.S. and Adler, R.P. (2008) Minds on Fire: Open

Education, the Long Tail, and Learning 2.0.

EDUCAUSE Rev., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 16-32.

Chatti, M. A. (2010a) Personalization in Technology

Enhanced Learning: A Social Software Perspective.

Shaker Verlag, PhD Dissertation, RWTH Aachen

University.

Chatti, M. A. (2010b) The LaaN Theory. In:

Personalization in Technology Enhanced Learning: A

Social Software Perspective. Aachen, Germany:

Shaker Verlag, 2010, pp. 19-42.

http://mohamedaminechatti.blogspot.de/2013/01/the-

laan-theory.html.

Chatti, M. A. (2012) Knowledge Management: A Personal

Knowledge Network Perspective. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 16(5).

Chatti, M. A., Schroeder, U., Jarke, M. (2012) LaaN:

Convergence of Knowledge Management and

Technology-Enhanced Learning. In: IEEE

Transactions on Learning Technologies, 5(2), 2012,

pp. 177–189.

Downes, S. (2005) E-Learning 2.0. ACM eLearn

Magazine, available at:

http://www.elearnmag.org/subpage.cfm?article=29-

1§ion=articles.

Gorman, G.E. and Pauleen, D.J., (2011), "The Nature and

Value of Personal Knowledge Management", in

Pauleen, D.J., Gorman, G.E. (Eds.), Personal

Knowledge Management: Individual, Organizational

and Social Perspectives. Gower Publishing Limited,

Farnham Surrey, England, pp. 1-16.

Grace, A. and Butler, T. (2005) Learning Management

Systems: A New Beginning in the Management of

Learning and Knowledge. Int’l J. Knowledge and

Learning, 1 (1/2), pp. 12-24, 2005.

Greven, C., Chatti, M. A., Thüs, H., Schroeder, U. (2014)

Context-Aware Mobile Professional Learning in

PRiME. mLearn 2014, CCIS 479, pp. 287–299.

Hildreth P. and Kimble, C. (2002), “The duality of

knowledge”, Information Research, Vol. 8 No. 1,

available at: http://informationr.net/ir/8-1/paper142.

html.

Holland, J. H. (1992). Complex adaptive systems.

Daedalus, 121(1), 17–30.

Holland, J. H. (1998). Emergence: From Chaos to Order.

Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley.

Jarche, H. (2010), “Personal Knowledge Management”,

available at: http://www.jarche.com/2010/01/pkm-in-

2010/

Kimble, C., Hildreth, P. and Wright, P. (2001),

“Communities of practice: going virtual”, in Malhotra,

Y. (Ed.), Knowledge Management and Business

Model Innovation, Idea Group Publishing, Hershey

(USA)/London (UK), pp. 220–234.

Lytras, M., Naeve, A. and Pouloudi, A. (2005) Knowledge

Management as a Reference Theory for E-Learning: A

Conceptual and Technological Perspective,” Int’l J.

Distance Education Technologies, 3(2), pp. 1-12,

2005.

Malhotra, Y. (2005), “Integrating knowledge management

technologies in organizational business processes:

Getting real time enterprises to deliver real business

performance”, Journal of Knowledge Management,

Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 7–28.

Mott, J. and Wiley, D. (2009) Open for Learning: The

CMS and the Open Learning Network. Education, vol.

15, no. 2, pp. 4-5.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge-

Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create

the Dynamics of Innovation, Oxford University, New

York.

Prusak, L. and Cranefield, J. (2011), "Managing your own

Knowledge: A Personal Perspective", in Pauleen, D.J.,

Gorman, G.E. (Eds.), Personal Knowledge

Management: Individual, Organizational and Social

Perspectives. Gower Publishing Limited, Farnham

Surrey, England, pp. 99-114.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for

the digital age. International Journal of Instructional

Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Retrieved

from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/

article01.htm.

Snowden, D. (2002), “Complex acts of knowing: Paradox

and descriptive self-awareness”, Journal of Knowledge

Managment, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp.100–111.

Snowden, D., Pauleen, D.J. and van Vuuren, S.J. (2011),

"Knowledge Management and the Individual: It’s

Nothing Personal", in Pauleen, D.J., Gorman, G.E.

(Eds.), Personal Knowledge Management: Individual,

Organizational and Social Perspectives. Gower

Publishing Limited, Farnham Surrey, England, pp.

115-128.

Thüs, H., Chatti, M. A., Yalcin, E., Pallasch, C. Kyryliuk,

B., Mageramov, T., Schroeder, U. (2012) Mobile

Learning in Context. International Journal of

Technology Enhanced Learning, 4(5/6), pp. 332–344.

Wilson, T. (2002), “The nonsense of knowledge

management revisited”, Information Research, Vol. 8

No. 1, available at: http://informationr.net/ir/8-

1/paper144.html.

LayeredKnowledgeNetworkinginProfessionalLearningEnvironments

371