A Business Model Approach to Local mGovernment Applications

Mapping the Brussels Region’s Mobile App Initiatives

Nils Walravens

iMinds-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 9, 1050, Brussels, Belgium

Keywords: Mobile Applications, mGovernment, Brussels, Business Models, Public Value.

Abstract: This paper uses business model theory as a framework to approach modern mobile government (mGov)

applications and explore the role of public bodies within the volatile and complex mobile services sector.

We propose and apply a new mapping methodology with a basis in business modelling that allows the

comparison of mobile app initiatives by governments and can support the development or adjustment of a

mobile strategy. We zoom in on the official applications released by different public administrations in the

Capital Region of Brussels, Belgium. We find that the laggard position Brussels is currently in could be an

opportunity to leapfrog in the field of mobile services, but that a focused vision, quadruple helix approach

and clearly formulated mobile strategy is quintessential to achieving this.

1 INTRODUCTION

The public sector has always been under some form

of pressure to innovate along the speed of the

market, both internally as an organisation and

externally, towards the services it provides to

citizens. In recent times, that high expected pace of

innovation has only grown, together with demands

and expectations from the public (Stylianou, 2014).

As a strategy geared towards meeting some of these

demands, organisations at different levels of

government have begun to initiate or commission

the development of mobile applications (“apps”) as a

new or complementary channel of (two-way)

communication with citizens (Hung et al., 2013), or

as a means of increasing citizen participation in

government processes (de Reuver et al., 2013).

Shifting public service provision to mobile devices

has also been referred to as mGovernment (as an

evolution of the field of eGovernment) (Kushchu

and Kuscu, 2003).

However, the mobile services and application

sector is a highly volatile one, perhaps even more so

than the ICT industry. Public administrations and

cities are faced with a significant challenge in this

regard, which mainly pertains to the high speed of

innovation, a shift in culture and mindset of the

organisation and the actual organisational aspects

related to creating, providing and supporting mobile

applications in a complex ecosystem that is – at least

in the Western hemisphere – dominated by two US

companies (Apple and Google) (Kahn, 2015).

It is in this complex context we propose business

model thinking as a framework to tackle some of

these challenges. Business models need to be

defined in their wider context here and not for

example be confused with business cases or the

revenue models of single enterprises (Janssen and

Kuk, 2007). Rather, we consider the entire value

network surrounding a particular mobile service and

offer a framework that allows public organisations to

find their “strategic fit” (Stabell and Fjeldstad, 1998)

within this complex ecosystem (Al-Debei and

Avison, 2010). To better frame the discussion and

help governments prioritise their mobile strategy, we

propose a new mapping methodology that allows the

direct comparison of mobile apps, based on the level

of government involvement required in their

development, as well as the potential public value

they may generate. We apply this method to the

Brussels Capital Region. As the capital of Belgium

and Europe, the region is faced with many

challenges that are representative of major

metropolitan areas around the world. Additionally,

the Region has a unique organisational and political

structure that makes taking joint initiative

challenging.

The main contribution of this paper then is to

introduce this mapping methodology based in

business model theory and immediately apply it to

Brussels. This approach will give more insight into

how business model thinking can help frame local

m-government strategies and support government in

setting up mobile service initiatives.

113

Walravens N..

A Business Model Approach to Local mGovernment Applications - Mapping the Brussels Region’s Mobile App Initiatives.

DOI: 10.5220/0005509701130124

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2015), pages 113-124

ISBN: 978-989-758-113-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 BUSINESS MODELS AND

mGOVERNMENT

This section will briefly explore the role that

business models may play in researching mGov

strategies. It also develops the set of parameters that

will be used as the foundation of the mapping

methodology.

2.1 Business Model Thinking in mGov

We approach the concept of a business model

similarly to e.g. Jullien (2004), Chesbrough (2006)

and Gawer (2010) as a value network consisting of

actors, roles and relationships that need to find a

strategic fit (Stabell and Fjeldstad, 1998) to deliver

value to end users. Using this operationalisation of

the concept, the underlying logic when applying it to

technological innovation is that it is not the

technology as such that is a determinant of success,

but rather the way in which the network of actors is

configured in generating added value around the

technology (Panagiotopoulos et al., 2012).

In this sense, business modelling can serve as a

means of bridging the gap between theoretical work

and the daily practice of policy makers and

government representatives. Applying a business

model logic or thinking to the public sector does not

have to be contradictory and business modelling as a

concept has already proved useful in the context of

eGovernment (Janssen et al., 2008; Jannsen and

Kuk, 2007, 2008). Yu (2013) also shows how the

concept of value proposition (an integral part of

business modelling theory) can be a guideline in

developing an integrated framework for analysing

and designing mGov strategies. Although the term

business model is naturally associated with a purely

commercial ecosystem, applying it in the context of

government does not necessarily imply imposing a

“business logic” to the public sector

(Panagiotopoulos et al., 2012). As mentioned, it

rather serves as a framework that allows policy

makers and government organisations to think about

their position within a complex value network and

prepare strategies as a response to potential issues of

control and value. This idea is built upon in the

following section, where the business model

framework we will use to design the mapping

methodology is explained.

2.2 mGov Business Model Parameters

and Mapping Methodology

In recent years, the focus of business modelling

(Hawkins, 2001) has gradually shifted from the

single firm to networks of firms, and from simple to

much more all-encompassing concepts (see e.g.

Linder and Cantrell, 2000; Faber et al., 2003). Due

to this shift, the guiding question of a business

model has become “Who controls the value network

and the overall system design” just as much as “Is

substantial value being produced by this model (or

not)” (Ballon, 2009).

Based on the tension between these two

questions, Ballon (2009) proposes a holistic business

modelling framework that is centred around control

on the one hand and creating value on the other. It

examines four different aspects of business models:

the value network, the functional (technical)

architecture, the financial model and the value

proposition. We build on these foundations, but

expand the matrix to include qualitative parameters

that are of additional importance when a public

entity contributes to the value proposition. Given

these organisations’ non-commercial logic, it is

imperative we take these additional parameters into

account when discussing (mobile) service business

models that involve public actors (Walravens and

Ballon, 2013). We propose an update to Ballon’s

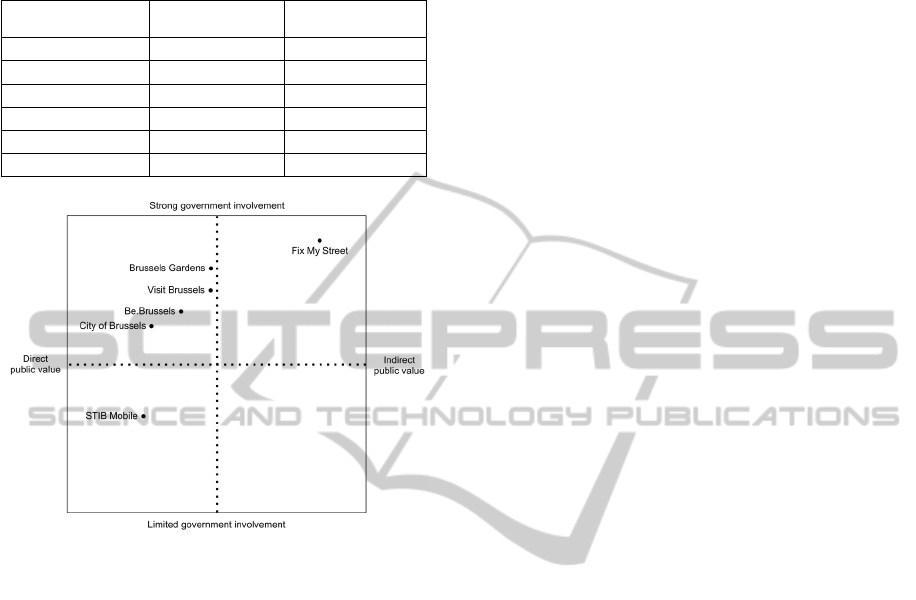

business model matrix, represented in Figure 1. The

left-hand side of the matrix offers parameters

pertaining to control and governance, whereas the

right-hand side parameters offer more insight into

value and public value issues.

Figure 1: Expanded business model matrix.

The detailed, qualitative description of all the

parameters of this expanded matrix allows for the

thorough analysis and direct comparison of complex

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

114

business models that involve public actors in the

value network. The parameters are quickly outlined

below.

Value Network

Control over assets: anything tangible or intangible

that could be used to help an organisation achieve its

goals.

Vertical integration: the level of ownership and

control over successive stages of the value chain.

Control over customers: looks into the party

maintaining the customer relationship and keeping

the customer data.

Good governance: refers to a striving towards

consensus and harmonization of interests (and

related rhetoric).

Stakeholder management: refers to the choices that

are made related to which stakeholders (be they

public, semi-public, non-governmental, private etc.)

are involved or invited to participate in the process

of bringing a service to end-users.

Technical Architecture

Modularity/integration: refers to the design of

systems and artefacts as sets of discrete modules that

connect to each other via predetermined interfaces.

Distribution of intelligence: refers to the particular

distribution of computing power, control and

functionality across the system.

Interoperability: refers to the ability of systems to

directly exchange information and services with

other systems.

Technology governance: highlights the importance

of transparency, participation and emancipation in

making technological choices and relates to the

digital divide.

Public data ownership: concerns the terms under

which data is opened up and to which actors.

Financial Architecture

Investment structure: deals with the necessary

investments (both capex and opex) and the parties

making them.

Revenue model: deals with the trade-off between

direct/indirect revenue models.

Revenue sharing model: refers to agreements on

whether and how to share revenues among the actors

involved in the value network.

ROPI: refers to the question whether the expected

value generated by a public investment is purely

financial, public, direct, indirect or combinations of

these, and how a choice is justified.

Public partnership model: explores how the

financial relationships between the private and

public participants in the value network are

constructed.

Value Proposition

Positioning: refers to marketing issues including

branding, market segments and identifying

competing services.

User involvement: refers to the degree in which

users can contribute to the value proposition.

Intended value: lists the basic attributes that the

product or service possesses, or is intended to

possess, and that together constitute the intended

customer value.

Public value creation: refers to the justification a

government provides initiating a specific service,

rather than leaving its deployment to the market.

Public value evaluation: questions whether an

evaluation of the generated public value takes places

and if this occurs ex-ante or ex-post.

A purely textual description of all these parameters

is not easily accessible and inspired us to translate

this into a mapping grid, which finds its basis in the

theoretical work of the matrix, but reduces the

complexity of representation. In this grid, it becomes

possible to compare divergent cases based on the

two central parameter sets of the matrix: control and

governance on the one hand and (public) value on

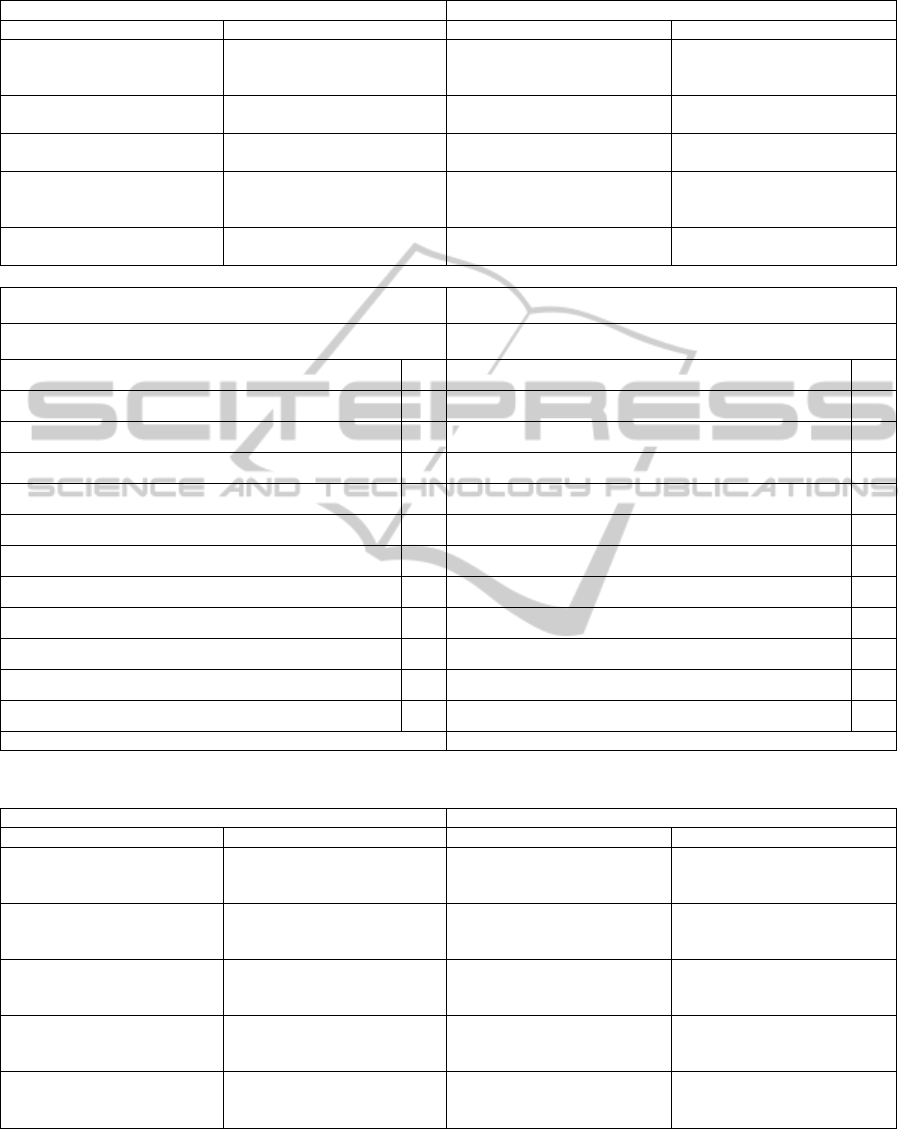

the other. The grid represented in Figure 2 allows us

to map different cases of (in our case mobile) city

services and identify how they compare to one

another.

Figure 2: Governance and public value grid.

The vertical axis refers to the governance parameters

described in the two left columns of the business

model matrix and provide an indication of the level

of control the city government has in providing the

service to citizens. The horizontal axis provides

insight into the type of value that is generated by the

services (the two right columns of the matrix) and

whether this public value is direct or indirect: direct

public value refers to a more individual, short-term

ABusinessModelApproachtoLocalmGovernmentApplications-MappingtheBrusselsRegion'sMobileAppInitiatives

115

Table 1: Overview of official Brussels mobile applications.

Name Dev. Platform Last update Category Rating iOS (by

x users)

Rating Android

(by x users)

Downloads (April

’14 Android)

Be.Brussels BRIC iOS/ Android 2012-12 Utilities 2 (1) 3,8 (29) 100-500

Brussels Gardens Tapptic iOS/ Android 2014-02 Lifestyle 4 (3) 3,9 (18) 1.000-5.000

City of Brussels GIAL Android 2015-02 Travel and Local NA 3,3 (7) 1.000-5.000

Fix My Street Bxl BRIC iOS/ Android 2015-01 Social 1,5 (9) 3,5 (44) 1.000-5.000

STIB Mobile STIB iOS/ Android 2013-02 Travel 2,5 (229) 4 (3391) 100.000-500.000

Visit Brussels Visit Brussels iOS/ Android 2012-12 Travel 3,5 (14) 2,2 (132) 10.000-50.000

value and relates to “what the public values”; while

indirect public value is more collective and long

term, and relates to “what adds value to the public

sphere” (Benington, 2011). This grid has been

validated in (Walravens and Ballon, 2013) and will

be used to map the official Brussels mobile city apps

further on in this article.

To determine the precise relative position of the

cases on the grid, a value or weight is attributed to

each of the parameters in the updated business

model matrix (see Section 4 and 5). In this sense,

qualitative indicators are translated to quantitative

ones in order to allow their direct comparison in a

structured way (see for example Michailidis and de

Leeuw, 2000). This approach is detailed and applied

in Section 4 and 5.

While this comparison is represented in a simple

fashion, it is based on an extensive qualitative

analysis that is based in literature, desk research,

policy document analysis and expert interviews with

stakeholders involved in the cases. A total of twenty-

two expert interviews was carried out in 2013 and

2014, tapping both national and international

expertise on mobile apps in general, as well as

specific insight into the Brussels cases.

3 THE BRUSSELS CONTEXT

Although its de facto role as capital of Europe, the

capital of Belgium and an interesting political

construction in a rather small geographical area,

Brussels is often neglected as a research topic in

some fields, precisely due to this complexity. The

Brussels Capital Region consists of the City of

Brussels, combined with the 19 municipalities that

encircle it and, with over one million inhabitants,

makes up the third Region of Belgium next to the

Flemish and Walloon Region. The Region, the City

and the municipalities all hold competences related

to ICT: for example, the City and the municipalities

are responsible for their own websites and any

online services they wish to offer to citizens (e.g.

social media communications), but the Region

operates an e-administration service called Irisbox,

where citizens can download documents related to

the Region’s competences (e.g. regional tax forms

and soil certificates), as well as documents related to

municipal competences (e.g. birth certificates,

parking permits and so on), although the availability

of these documents depends on the municipality.

These distributed competences can make the

development of common policies a challenge.

One example of this is the City and Region’s

approach to open data. While the cooperation

models and exact terms are still crystallizing across

Europe and the world, it is accepted that open data is

and will be an important component of innovative

urban services (whether they be mobile or not) (EC,

2012). In Brussels, open data initiatives are

distributed; GIS data is managed and opened by the

Brussels Region Informatics Centre (BRIC) while

more typical datasets (e.g. ATM locations, public

toilets etc.) are the responsibility of the

municipalities and in the case of the City of Brussels

opened up by GIAL (Centre de Gestion

Informatique des Administrations Locales), a non-

profit that provides ICT-services to local

administrations, including the City of Brussels. This

again makes a common approach difficult.

While there are certain issues and questions to be

raised (for example on ICT-expenditure in Hillenius,

2013), the Region also takes positive initiatives in

the area of mobile services, launching initiatives

such as FixMyStreet Brussels and these will be

analysed using the framework introduced above.

4 OFFICIAL BRUSSELS APPS

The number of official apps by the City of Brussels,

the Region or any of its institutions is limited. Table

1 provides an overview of the official apps for

Brussels. For each case, all the parameters of the

expanded business model matrix described above

are discussed in a table, available in annex to this

paper. The material for the cases was gathered from

policy documents, publicly available information

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

116

and expert interviews with people involved with

them. From this analysis, a score on a 5-point Likert

scale is given to each of the parameters that help

determine the position of the case on the governance

and public value grid. This scale ranges from -2

(strongly disagree) to 2 (strongly agree), indicating

the level of agreement with the statements in the

tables in annex. This scoring allows us to compare

the cases with each other and draw some

conclusions on the Brussels approach to mGov

services.

4.1 Be.Brussels

The Be.Brussels app developed by BRIC applies to

the Brussels Capital Region and offers a map with

points of interest and useful phone numbers, as well

as direct access to the Region’s social media

streams.

Given that the main goal of the app is providing

information to individual citizens, we see a score

that leans towards a direct public value. Although

their relation is very strong, the fact that this app was

developed by an individual organisation and not

within a Brussels administration is reflected in the

government involvement score. Since our data

gathering phase, this app has been removed from

Google Play and the iTunes App Store for unclear

reasons. The breakdown of all parameters and scores

can be found in annex to this paper.

4.2 Brussels Gardens

Brussels Gardens was created by Brussels

Environment (IBGE), one of the Region’s

administrations responsible for the study, monitoring

and management of air, water, soil, waste and

nature. The app provides an overview of the green

spaces and their uses in the Region as well as

information on the history of the green spaces, their

special characteristics and the conservation of plants

and wildlife.

The almost neutral score in the public value

column can in this case be explained by the fact that

the app provides information to individuals, but its

broader goal is to increase appreciation and use of

green spaces in Brussels.

4.3 City of Brussels

The City of Brussels app only pertains to this level

of government (the City and not the Region) and is

developed by a different non-profit organization

(GIAL) than the one working for the Region

(BRIC). It provides news, public transport

information, contact information, the city’s social

media and a map with points of interest.

Similarly to the Be.Brussels app, the fact that the

app is not developed by a Regional administration is

reflected in the lower government involvement score

and the public value it generates is more direct.

4.4 FixMyStreet Brussels

FixMyStreet Brussels is the local implementation of

the well-known issue reporting service, first

developed in the UK. It allows citizens to report

issues with city furniture or in the public space, but

was until very recently limited to potholes, bad road

surface or missing road markings in the case of the

Brussels Region.

In this case a very high level of government

involvement was required to make the app possible

and the public value is aimed at the collective.

4.5 STIB Mobile

STIB mobile is the official app of the Brussels

public transport company and allows users to consult

real time departures and timetables at STIB stops.

Since the STIB acts as an independent company

from the city government (even though it is publicly

funded), the level of government control is lower in

this case and the created public value is direct.

4.6 Visit Brussels

The final official app is Visit Brussels by the tourism

department of the Region, bringing together all

kinds of touristic information and offering a

comprehensive city guide. The app was developed

by Visit Brussels and is based on an internal

database of points of interest.

Similarly to the Brussels Gardens app, we notice

a balance between a direct and indirect value in the

case of Visit Brussels. This can be explained as a

result of the combination of the individual

information the app provides to visitors and the

more long-term and collective goal of boosting

tourism and the attractiveness of the city.

5 MAPPING

Bringing together the scores of the six publicly

developed Brussels applications (see annex) allows

us to map them on the governance and public value

grid introduced in Section 2. The scores are directly

translated to coordinates on the grid, which consists

of two 20-point axes. The coordinates and the

ABusinessModelApproachtoLocalmGovernmentApplications-MappingtheBrusselsRegion'sMobileAppInitiatives

117

mapping are represented in the following table and

figure.

Table 2: Coordinates.

Public value

(x-axis)

Government

involvement (y-axis)

Be.Brussels -5 7

Brussels Gardens -1 13

City of Brussels -9 5

FixMyStreet Brussels 14 17

STIB Mobile -7 -10

Visit Brussels -1 10

Figure 3: Governance and public value grid mapping

Brussels’ cases.

Although we of course expected most apps to

score quite highly when it comes to government

involvement (as all are developed by official

government organisations), this is slightly more

nuanced. In the cases of FixMyStreet, Brussels

Gardens and Visit Brussels the official Brussels

administrations were directly involved in the

ideation, development or commissioning of the apps.

Be.Brussels, City of Brussels and STIB Mobile were

created by semi-public organisations that work

directly for the Brussels Capital Region. As such and

depending on their role, they score lower on the

government involvement axis.

We clearly see that most apps were created with

a direct public value in mind, meaning they are

aimed at individuals and on providing information,

without much possibility for interaction or a long-

term approach. The only exception is FixMyStreet,

which allows citizens to report issues that are acted

upon by the local administration. The system has

been integrated as a single point of contact into the

daily operations of the Brussels Mobility

administration and it is part of a long-term vision to

add more types of reports (and related stakeholders)

to the list of options for citizens. The end goal is

increasing communication with citizens and at the

same time improving the general quality of life

around the City and Region, pointing again to the

app’s indirect public value. By most definitions and

operationalisations of the mGovernment concept

(laid out in the first two sections of this paper),

FixMyStreet is probably one of the better examples

of what mobile government services (should) look

like.

When interpreting the scores for these six

official Brussels applications, we come to the

conclusion that basic information provision to

individual citizens appears to be the most popular

strategy amongst administrations. This is also the

most careful one. It is not surprising in the context of

budgetary constraints that (local) governments face

today, that more long-term, structural and

participatory initiatives such as FixMyStreet are

more exception than rule. Nevertheless, the

interview round showed that the administration

involved is serious about the service and that the

investment made is too important to view it as an

experiment. The other apps under discussion are

more easily referred to as first try-outs in

mGovernment and in most cases leave features or

uptake to be desired. While experimentation

certainly needs to be encouraged, we argue that in

order to make a long-term impact in this area and

begin tackling governance challenges through

mobile services, the mobile application market and

related economy has now sufficiently matured for

governments to move beyond experimentation and

take the lessons learned locally and internationally to

develop a true mobile strategy. Since Brussels is

playing something of a laggard role when it comes

to both Smart City initiatives and mobile application

creation, the opportunity to leapfrog in this space

should be valorised today. The FixMyStreet case

illustrates that involving all relevant stakeholders

(municipal administrations, mayors, local energy

and telecom players, citizens and civil society) in a

quadruple helix approach is key to a successful and

broadly supported mobile government service, but

one that may require higher investments.

6 DISCUSSION

A government body can use the grid to map any

mobile service initiatives it has running or plans to

undertake, to identify whether their level of

involvement has the desired results related to the

public value it wants to generate, and thus if the

actions they take are aligned with the policy goals

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

118

they want to achieve. The different quadrants of the

grid give insight into the approach taken by

government: the strategy in the bottom-right

quadrant focuses on creating a positive climate for

long-term innovation and improvements to the

general quality of life for as many citizens as

possible; the bottom-left quadrant aims to stimulate

projects and initiatives that have a more immediate

and clear benefit to citizens that potentially show

signs of engagement themselves; while the top-right

quadrant sees a more integrated approach to solving

long-term issues typical to major metropolitan areas,

wherein the city takes a leading role; compared to

the final top-left quadrant that sees an applied

approach by the city to create some immediate value

for individual citizens, by increasing the ease-of-life

and attractiveness of their city. These represent four

quite different strategies to providing mGov services

to citizens to be considered by government

authorities and public bodies looking towards or

providing those services.

While this mapping offers a visual representation

of the Brussels Region’s mGov initiatives, the main

value of the analysis lies in the business model

approach taken to this challenge. By considering all

the business model aspects pertaining to a modern

mobile service initiative, and including parameters

that are specific to public sector involvement, it has

been our aim to provide policy makers at the local,

regional or national level with a way to better

consider the implications of a mobile strategy. As

was mentioned earlier, business modelling as a

framework should not only be associated with

commercial initiatives, but rather be seen in a

broader context. When operationalised in a

methodology comparable to the one presented in this

paper, business modelling can provide more insight

into the challenges pertaining to mobile in the public

sector as well.

A limitation of this work pertains to the focus of

the original matrix on the relations between firms

and organizations and not so much on the internal

organizational structures of companies or agencies.

Since the newly introduced parameters build on the

original matrix, there is no specific attention to

internal organizational processes. As government is

also a system of systems with different actors and

roles, this aspect should be further explored.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This article set out to frame how business modelling

may also provide a framework to mGovernment,

rather than being confined to purely commercial

initiatives. We did this by expanding on an existing

business model framework to include parameters

specific to the public sector. We then apply this to

all official Brussels apps, map them on the newly-

developed grid and come to the conclusion that these

apps are mostly aimed at short-term public value

generation and providing localised information to

individual citizens. FixMyStreet is the only Brussels

case that shows a mid to long-term strategy that has

a mobile application at its core. It is then also a

showcase of how an urban challenge can (begin to)

be tackled through a qualitative mGov application

that is well thought out and enables citizen

participation.

Our conclusion then is that Brussels is taking

careful steps when it comes to smart mGov apps, but

that this hesitance can for the most part be explained

by the institutional complexity of the Region and the

(for now) lack of a single mobile strategy as a

consequence. The FixMyStreet case shows that it is

possible for the Region to set up a long-term and

integrated approach, but this is likely to take more

time and resources. Nevertheless, we believe

Brussels can learn from the increasing maturity in

the mGovernment and apps sector and leverage its

potential to leapfrog in this space. To do so and label

itself as “smarter” than before, an integrated and

open-minded approach to mobile services, which

involves all relevant stakeholders in the city through

a quadruple helix approach, will be a conditio sine

qua non to achieving this.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was performed at the Vrije

Universiteit Brussel and iMinds, and supported by

an Innoviris PRFB grant (Brussels Capital Region).

REFERENCES

Al-Debei, M. M., Avison, D., 2010. Developing a unified

framework of the business model concept. European

Journal of Information Systems, 19(3), 359-376.

Ballon, P., 2009. Control and Value in Mobile

Communications. PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit

Brussel, Belgium.

Benington, J., 2011. From Private Choice to Public Value?

In Benington, J., Moore, M., eds. Public Value:

Theory and Practice. Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 31-49.

Chesbrough, H., 2006. Open Business Models: How to

Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape, Harvard

Business School Press. Boston, Massachusetts:

De Reuver, M., Stein, S., Hampe, J. F., 2013. From

eParticipation to mobile participation: Designing a

ABusinessModelApproachtoLocalmGovernmentApplications-MappingtheBrusselsRegion'sMobileAppInitiatives

119

service platform and business model for mobile

participation. Information Polity, 18(1), 57-73.

Faber, E., Ballon, P., Bouwman, H., Haaker, T., Rietkerk,

O., Steen, M., 2003. Designing business models for

mobile ICT services. Proceedings of 16th Bled E-

Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia.

Gawer, A., 2010 Towards a General Theory of

Technological Platforms. Proceedings of DRUID

2010, Imperial College London Business School, June

16-18.

Hawkins, R., 2001. The Business Model as a Research

Problem in Electronic Commerce. STAR Project Issue

Report No. 4, SPRU – Science and Technology Policy

Research, Brighton.

Hillenius, G., 2013. Jurisdiction Stops Brussels Region

from Sharing FixMyStreet. Joinup, European

Commission, 14 June.

Hung, S. Y., Chang, C. M., Kuo, S. R., 2013. User

acceptance of mobile e-government services: An

empirical study. Government Information Quarterly,

30 (1), 33-44.

Janssen, M., Kuk, G., 2007. E-Government business

models for public service networks. International

Journal of E-Government Research, 3(3), 54-71.

Janssen, M., and Kuk, G., 2008. E-Government business

models: Theory, challenges and research issues. In M.

Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), E-Government diffusion, policy,

and impact: Advanced issues and practices (pp. 1-12)

IGI Global.

Janssen, M., Kuk, G., Wagenaar, R., 2008. A survey of

web-based business models for E- Government in the

Netherlands. Government Information Quarterly,

25(2), 202-220.

Jullien, B., 2004. Two-Sided Markets and Electronic

Intermediation. IDEI Working Papers 295, Institut

d'Économie Industrielle (IDEI), Toulouse, France.

Kahn, J., 2015. iOS and Android increase duopoly on

smartphone market to 96%. 9to5mac. 24 February.

Konings, R., 2014. Belgische app-ontwikkelaars

ondertekenen eTIC-charter voor mobiele applicaties.

Agoria, Press Release, 14 May.

Kushchu, I., Kuscu, M., 2003. From e-Government to m-

Government: Facing the Inevitable. In Proceedings of

the 3rd European Conference on E-Government, pp.

253–260, Dublin, Ireland.

Linder, J., Cantrell, S., 2000. Changing Business Models:

Surveying the Landscape. Institute for Strategic

Change Report, Accenture, New York, NY.

Michailidis, G., de Leeuw, J., 2000. Multilevel

Homogeneity Analysis with Differential Weighting.

Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 32(3/4),

pp.411-442.

Panagiotopoulos, P., et al., 2012, A business model

perspective for ICTs in public engagement.

Government Information Quarterly, 29(2), 192-202.

Stabell, C., Fjeldstad, O., 1998. Configuring Value for

Competitive Advantage. Strategic Management

Journal, 19(5), pp.413-437.

Stylianou, A., 2014. Mobile by Default? Leveraging

Mobile Technology to Extend eGovernments Reach

and Scope, Workshop Policy Brief, ePractice,

European Commission. 30 June.

Walravens, N., Ballon, P., 2013 Platform Business Models

for Smart Cities. IEEE Communications Magazine, 51

(6), June, pp.2-9.

Yu, C.-C., 2013. Value Proposition in Mobile

Government, In Wimmer, M., Janssen, M., Scholl, H.,

eds., Electronic Government, Springer Berlin

Heidelberg, pp. 175-187.

APPENDIX

The business model parameter descriptions and the

scores of each case are appended to this paper.

Tables 3 and 4: Business model parameters and scores for Be.Brussels.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: with BRIC,

gathering official information

Modularity: not particularly

modular approach, uses BRIC’s

URBIS maps

Investment structure: budgeted in

short term by BRIC

User involvement: limited to

social networking links

Vertical integration: quite

integrated into the city

organisation, although BRIC is

an independent entity

Distribution of intelligence: an

internet connection is required to

access main functions

Revenue model: indirect, public

funds

Intended value: access to POIs

and city contact information

Control over customers: with the

Region, marketed as the Region’s

app

Interoperability: available for the

two most important platforms

Revenue sharing: no revenue

sharing

Positioning: towards individual

citizens looking for information

Good governance: not

particularly used in surrounding

rhetoric

Technology governance:

inclusion not emphasised,

distribution of info

ROPI: one-way information

channel

Public value creation: mainly

one-way information channel

Stakeholder management: BRIC

is the only involved stakeholder

Public data ownership: all used

data is publicly available

elsewhere

Public private partnership model:

no structural PPP present

Public value evaluation:

internally evaluated

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

120

Tables 3 and 4: Business model parameters and scores for Be.Brussels (cont.).

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city 1 Investment structure goal is long term/collective -2

Vertically integrated within city organisation -1 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 2 Revenue sharing set up over long term 0

Good governance aspects emphasised -1 ROPI is long term 1

Stakeholder management organised by city 1 PPP model is structural 0

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules with city 2 User involvement: individual or collective 1

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city 1 Intended value: short or long term 1

Interoperability emphasised 1 Positioning aimed at collective -2

Technology governance: inclusion and openness emphasised 0 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective -2

Public data ownership defined by city 1 Public value evaluation organised -2

Score 7 -5

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

Tables 5 and 6: Business model parameters and scores Brussels Gardens.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: almost

completely with Brussels

Environment

Modularity: not particularly

modular, but uses Google Maps

Investment structure: in short-

term budget of IBGE

User involvement: limited to

none

Vertical integration: app was

created by external developer but

is managed by IBGE

Distribution of intelligence:

internet connection required to

load data

Revenue model: no revenue

model

Intended value: access to green

spaces and environment

Control over customers: free app

clearly from IBGE

Interoperability: both iOS and

Android versions available

Revenue sharing: indirect, public

funds

Positioning: towards individual

citizens looking for green space

Good governance: quite present

given the topic of the app and

focus on sustainability

Technology governance:

inclusion not specifically

emphasised

ROPI: information distribution

Public value creation: promote

green spaces in Brussels

Stakeholder management: IBGE

is the only main stakeholder

Public data ownership: most

presented data is publicly

available but not centralised

Public private partnership model:

no structural PPP in place

Public value evaluation:

evaluated internally

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city 2 Investment structure goal is long term/collective -2

Vertically integrated within city organisation 1 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 1 Revenue sharing set up over long term 0

Good governance aspects emphasised 2 ROPI is long term 1

Stakeholder management organised by city 0 PPP model is structural 0

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules with city 1 User involvement: individual or collective 1

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city 2 Intended value: short or long term 2

Interoperability emphasised 1 Positioning aimed at collective -2

Technology governance: inclusion and openness emphasised 1 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective 1

Public data ownership defined by city 2 Public value evaluation organised -2

Score 13 -1

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

ABusinessModelApproachtoLocalmGovernmentApplications-MappingtheBrusselsRegion'sMobileAppInitiatives

121

Tables 7 and 8: Business model parameters and scores for City of Brussels.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: based on

public information, developed by

GIAL

Modularity: not particularly

modular

Investment structure: short-term

budget of GIAL

User involvement: very limited to

none

Vertical integration: internally

developed

Distribution of intelligence: need

for internet connection

Revenue model: indirect revenue,

public funding

Intended value: information

channel, static

Control over customers: with the

City of Brussels

Interoperability: only Android,

based on open data sets

Revenue sharing: no revenue

sharing

Positioning: marketed as the

city’s app

Good governance: not

particularly emphasised, info

distribution

Technology governance: only

available on Android

ROPI: information distribution

Public value creation: wider

access to information

Stakeholder management: GIAL

is the only main stakeholder

Public data ownership: publicly

available data (as open data)

Public private partnership model:

no structural PPP

Public value evaluation: limited

internal evaluation

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city 1 Investment structure goal is long term/collective -2

Vertically integrated within city organisation -1 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 2 Revenue sharing set up over long term 0

Good governance aspects emphasised -1 ROPI is long term 1

Stakeholder management organised by city 1 PPP model is structural 0

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules with city 1 User involvement: individual or collective -2

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city 1 Intended value: short or long term -2

Interoperability emphasised 1 Positioning aimed at collective -1

Technology governance: inclusion and openness emphasised -1 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective -2

Public data ownership defined by city 1 Public value evaluation organised -1

Score 5 -9

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

Tables 9 and 10: Business model parameters and scores for FixMyStreet Brussels.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: shared

between BRIC, cabinet and

Mobile Brussels

Modularity: quite modular

architecture, links to other

services possible

Investment structure: public funds

from regional ICT cabinet

User involvement: primordial to

use of the service

Vertical integration: growing

internally

Distribution of intelligence:

centrally hosted, data connection

required

Revenue model: indirect, public

funds

Intended value: increased internal

efficiency and fixing issues

Control over customers: with the

city/region

Interoperability: open source,

middleware required to link to

existing systems

Revenue sharing: no revenue

sharing

Positioning: branded as

government service

Good governance: emphasised,

transparency highlighted

Technology governance: Android

and iOS, phone number available

but differently branded

ROPI: both internal and external

efficiency gains, transparency

Public value creation: increased

citizen interaction, fixing issues

Stakeholder management:

challenging and organised by

external consultant

Public data ownership: collected

reports not open data

Public private partnership model:

not present

Public value evaluation:

internally evaluated, stimulation

towards municipalities

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

122

Tables 9 and 10: Business model parameters and scores for FixMyStreet Brussels (cont.).

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city 2 Investment structure goal is long term/collective 2

Vertically integrated within city organisation 2 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 2 Revenue sharing set up over long term 0

Good governance aspects emphasised 2 ROPI is long term 2

Stakeholder management organised by city 1 PPP model is structural 0

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules with city 2 User involvement: individual or collective 2

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city 2 Intended value: short or long term 2

Interoperability emphasised 2 Positioning aimed at collective 2

Technology governance: inclusion and openness emphasised 1 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective 2

Public data ownership defined by city 1 Public value evaluation organised 2

Score 17 14

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

Tables 11 and 12: Business model parameters and scores for STIB Mobile.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: with STIB

Modularity: app links to real-time

position system of STIB

Investment structure: public funds User involvement: not enabled

Vertical integration: integrated

with STIB location system

Distribution of intelligence:

internet connection required

Revenue model: no revenue

model present

Intended value: access to real-

time information

Control over customers: with

STIB, no explicit reference to

city or region

Interoperability: no open data,

closed approach

Revenue sharing: no revenue

sharing

Positioning: branded as STIB

service

Good governance: not

particularly emphasised

Technology governance:

Android, web and iOS apps

ROPI: access to real-time

location of public transport

Public value creation: increased

and real-time information

provision

Stakeholder management: STIB

is only main stakeholder

Public data ownership: closed

data owned by STIB

Public private partnership model:

not present

Public value evaluation: no public

evaluation of app

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city -1 Investment structure goal is long term/collective -2

Vertically integrated within city organisation -1 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 0 Revenue sharing set up over long term 0

Good governance aspects emphasised 0 ROPI is long term -2

Stakeholder management organised by city -1 PPP model is structural -1

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules by city -2 User involvement: individual or collective -1

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city -1 Intended value: short or long term -2

Interoperability emphasised -2 Positioning aimed at collective 1

Technology governance: inclusion and openness

emphasised 0 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective 1

Public data ownership defined by city -2 Public value evaluation organised -1

Score -10 -7

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

ABusinessModelApproachtoLocalmGovernmentApplications-MappingtheBrusselsRegion'sMobileAppInitiatives

123

Tables 13 and 14: Business model parameters and scores for Visit Brussels.

Control and governance parameters Value and public value parameters

Value network Technical architecture Financial architecture Value proposition

Control over assets: mostly with

Visit Brussels

Modularity: uses Open Street

Map

Investment structure: public funds

User involvement: none, apart

from social media sharing

Vertical integration: integrated in

Visit Brussels organisation

Distribution of intelligence: a

large initial download is required,

offline

Revenue model: no revenue

model present

Intended value: providing

touristic information on map

Control over customers: with

Visit Brussels/the Region

Interoperability: closed system

Revenue sharing: potential

revenue sharing with event

organisers

Positioning: branded as

City/Regional service

Good governance: present in

general communication

Technology governance:

Android, iOS, no web app

ROPI: increasing information on

and attractiveness of Region

Public value creation: individual

information provision

Stakeholder management: Visit

Brussels is main stakeholder

Public data ownership: no open

data for POIs, Open Street Map

Public private partnership model:

not present

Public value evaluation: internal

evaluation

Limited to strong government involvement Direct to indirect public value

Value network Financial architecture

Control over assets with city 1 Investment structure goal is long term/collective -1

Vertically integrated within city organisation 2 Revenue model is direct or indirect 0

Control over customers with city 2 Revenue sharing set up over long term 1

Good governance aspects emphasised 1 ROPI is long term 2

Stakeholder management organised by city 1 PPP model is structural 0

Technical architecture Value proposition

Modularity: control over modules with city 1 User involvement: individual or collective -1

Distribution of intelligence: centralised with the city 1 Intended value: short or long term -2

Interoperability emphasised -1 Positioning aimed at collective -2

Technology governance: inclusion and openness emphasised 1 Public value creation aimed at long term/collective 1

Public data ownership defined by city 1 Public value evaluation organised 1

Score 10 -1

higher=more involvement higher=indirect

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

124