A Model for Digital Content Management

Filippo Eros Pani, Simone Porru and Simona Ibba

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of Cagliari, Piazza d'Armi, Cagliari, Italy

Keywords: Content Management, Digital Libraries, Taxonomy, Metadata Standards.

Abstract: Digital libraries work in complex and heterogeneous scenarios. The quantity and diversity of resources,

together with the plurality of agents involved in this context, and the continuous evolution of user-generated

content, require knowledge to be formally and flexibly organized. In our work, we propose a library

management system - which specifically addresses the Italian context - based on the creation of a metadata

taxonomy that analyses the existing management standards, connects them, and associates them with the

multimedia content, through a comparison with popular metadata standard employed for User-Generated

Content. The approach is based on the conviction that cultural heritage should be managed in the most flexible

way through the use of open data and open standards that promote knowledge interoperability and exchange.

Our management model for the proposed metadata aims to be a useful instrument for the greater sharing of

knowledge in a logic of reuse.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital libraries are complex systems that connect

institutional resources and capabilities, but also offer

unparalleled opportunities for new and improved user

services (Schwartz, 2000). These systems have to

guarantee ease of access, sharing, storage and

retrieval of resources that are produced by different

organizations, as well as manage their heterogeneity.

The degree of complexity and richness of information

requires actions in a logic of strong cooperation and

interoperability.

The National Library Service (SBN) is the Italian

libraries network. The ISBN network is composed by

state libraries, council libraries, universities, schools,

academies, and public and private institutions which

operate in different areas. The main goal of this

network is to remove the fragmentation of library and

effectively manage the information that originates

from different types of digital content (books,

audiobooks, ebooks, audio, databases, music,

websites, documents).

As asserted in (Bellahsene et al., 2011), requiring

heterogeneous information systems to cooperate and

communicate has now become crucial, as such

cooperating systems have to match, exchange,

transform and integrate large data sets from different

sources and of different structure in order to enable

seamless data exchange and transformation. This is

also true for a national libraries network.

The purpose of this work is to formalize

knowledge through the creation of a metadata

taxonomy through the analysis and the integration of

existing metadata schemas and the study of the main

digital libraries. In the digital libraries context there

are different resources: some of these are unstructured

or described with different metadata schemas.

Resources integration is a complex activity, since the

quantity of existing metadata schemas is so large as

to make the realization of a single access to the

service difficult.

Our work aims to find a relationship between the

main metadata schemas through their comparison.

The final result is a taxonomy, which provides

innovative metadata with respect to resource

classification, especially ebooks, which nowadays

play a fundamental role in the context digital libraries.

Through the use of the proposed taxonomy, it is also

possible to effectively manage metadata related to

rights management, with the final goal of making it

easier to find the information truly regarded as

relevant by the final user.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we

propose an overview about the state of the art. In

section 3 we discuss our approach for multimedia

content management, based on the explanation of

each of the three phases on which it is built. In section

240

Pani F., Porru S. and Ibba S..

A Model for Digital Content Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0005512202400247

In Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Data Management Technologies and Applications (DATA-2015), pages 240-247

ISBN: 978-989-758-103-8

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

4 we describe the case study and the structure of the

resulting taxonomy; finally, in section 5 the

conclusions are presented, together with some

reasoning about the future evolution of the work.

2 RELATED WORK

Metadata are used as a means to retrieve digital

objects in a punctual and precise way through a single

access point. Metadata describe structure, features,

conditional use and management information related

to the associated resources. In the digital libraries

context, the metadata have the following features:

identify and find the resources (descriptive metadata),

manage resources and ensure acquisition,

management and use on the basis of existing rights

and licenses (management metadata). Metadata also

describe existing relationships between resource

components, to make the information easily

accessible with a higher granularity level (structural

metadata) (Hill et al., 1999).

Dublin Core (DC) is the most common standard.

Its core consists of 15 elements that are part of a larger

set of metadata vocabularies and technical

specifications maintained by the Dublin Core

Metadata Initiative (DCMI). The essential function of

the Dublin Core is maintained by the DCMI and is

represented by the basic the so-called simple DC (i.e.,

without 'qualifiers'). The DC is also used for the

exchange of metadata according to the Open Archive

Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI –

MHP) (Lagoze and Van de Sompel, 2003). The need

to express certain values with higher granularity led

to the definition of qualifiers. The full set of

vocabularies (i.e., the DCMI Metadata Terms, also

includes a set of resource classes including the DCMI

Type Vocabulary, vocabulary encoding schemas, and

syntax encoding schemas. The schema can be

extended by defining additional elements

appropriately identified by a prefix that indicates the

schema they belong to. Additional metadata can be

inserted through application profiles, specifically

tailored for the context and not covered by the basic

schema. As the DC is a descriptive metadata schema,

additional technical and management metadata can be

useful for the management of the described resources.

With the Adobe Extensible Metadata Platform

(XMP) is possible to embed metadata into files during

the content creation process. XMP allows for

meaningful content information to be captured (such

as titles and descriptions, searchable keywords, and

up-to-date author and copyright information). It is

freely available because it is an open source standard

since early 2012. XMP is also an ISO standard

(16684-1), and supports many image formats,

dynamic media formats, video package formats,

adobe applications formats, markup formats and

document formats.

Exif standard (Exchangeable image file format) is

an international open-standard used for tagging image

files with metadata, or adding information about the

image. It is supported by both the TIFF and JPEG

formats. When a picture is taken with a digital

camera, Exif data are automatically embedded into

the image. This typically includes the exposure time

(shutter speed), f-number, ISO setting, flash (on/off),

date and time, brightness, white balance setting,

metering mode, sensing method, and information

about copyright and GPS, which is used for

"geotagging" photos.

Different standards are usually not designed for a

combined use. Such problems arise especially with

the dissemination of user generated content found on

social media websites such as Flickr, YouTube, or

Facebook (Suárez-Figueroa et al., 2013). Many

efforts to build ontologies that can bridge this

semantic gap have been done for various applications

(annotation areas, multimedia retrieval, etc.),

sometimes involving different national or

international initiatives.

Many solutions have been proposed to provide a

formal classification that could take into account the

relationships between different multimedia metadata

(Stadhofer et al., 2013). An example for a complex

standard is MPEG-7. MPEG-7 provides a rich set of

complex descriptors that mainly focus on expressing

low-level features of images, audio, and video.

Several approaches have been published

providing a formalization of MPEG-7 as an ontology

(Dasiopoulou et al., 2009); (Hunter, 2003), or the

Core Ontology on Multimedia (Arndt et al., 2007).

Although these ontologies provide clear semantics for

the multimedia annotations, they still focus on

MPEG-7 as the underlying metadata standard. More

importantly, these ontologies basically provide a

formalization of MPEG-7, but do not focus on the

integration of different standards. Ontologies based

on the MPEG-7 standard, like the one proposed in

(García and Celma, 2005), the one proposed in

(Tsinaraki et al., 2004), and the MPEG-7 Upper MDS

(Hunter, 2001) developed within the Harmony

Project, which are all represented in OWL, are not

suitable for an immediate use in the Italian digital

library scenario, both for the higher emphasis placed

on audio and video content than on other multimedia

objects, and for the interoperability issues connected

with the exploitation of the OAI-PMH.

AModelforDigitalContentManagement

241

The Multimedia Metadata Ontology (M3O) is a

possible solution to metadata standard integration

issues (Scherp et al., 2012). The M3O provides a

generic modeling framework for representing

sophisticated multimedia metadata. It allows for the

integration of the features provided by the existing

metadata models and metadata standards.

Another proposed solution is the Media Resource

Ontology, created by the W3C Media Annotation

Working Group. The Media Resource Ontology is an

ontology based on a mapping effort between many

different multimedia metadata standards, including

Exif 2.2, MPEG-7, METS (Gartner, 2002), NISO

(Davis, 2004), and XMP. It is mainly web-oriented,

and, being structured following other standards, does

not analyze the specific elements of the context at

hand.

PICO AP is a DC application profile used by

Cultura Italia (Buonazia et al., 2007). PICO AP is an

XML metadata schema oriented to the exploitation of

OAI-PMH. PICO AP aims at providing metadata

harvesting functionalities also in the presence of

different schemas, so addressing the interoperability

issues.

The MAG (Pierazzo, 2006) schema is an

application profile that interacts with other standards,

namely the Dublin Core, and the NISO (Davis, 2004).

MAG aims to provide formal specifications for the

collection, transfer and dissemination of metadata and

digital data in their archives. MAG schema defines a

metadata taxonomy that can achieve a higher degree

of independence, both from the specific application

context, and from software and hardware. MAG

metadata are defined through the XML format, in

order to be compliant with the OAI-PMH standard.

As an extensible standard, MAG is a suitable

candidate as a starting point for the construction of a

metadata taxonomy.

With respect to mapping, the work by (Euzenat

and Shvaiko, 2013) is certainly worth of

consideration, as we decided to map entities taken

from different classifications. On the other hand, the

FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic

Resources) (IFLA, 1998) model serve as a guide for

understanding the relationships between metadata

taken from diverse classifications.

3 THE PROPOSED APPROACH

Our aim is to effectively use the reference knowledge

(ontology, taxonomy, metadata schema) to start

classifying the information related to the context of

modern digital libraries.

We propose a model that starts from the

comparison of different classifications of the same

domain. In the second phase, the knowledge is

analysed by pinpointing, among the available

information, what is needed, in order to define a

reference glossary to describe the data.

Thus pinpoint, for each single metadata we found,

where the information can be found. This information

represent the context in which the object is inserted.

Thus, we consider the semantic concept taking the

bias of the context into account.

Starting from this knowledge base (KB), further

refining can be made by re-analysing the information

in different phases: with a first phase, checking if the

information that is not represented by the chosen

formalization can be formalized; with a second phase,

analysing if some information found on the Web sites

can be connected to formalized items; finally, we try

to reconcile these concepts through the refining

phase, presented in section 4.

This is obviously needed only for the information

to be represented. The knowledge that we want to

represent is the one considered of interest by the

users: for this reason, the most important pieces of

information are chosen. The final outcome of the

proposed work is a metadata taxonomy, aimed at

effectively representing the knowledge of interest in

the domain of the digital libraries.

4 CASE STUDY

According to an industrial project concerning the

implementation of Web-based platform for both

library cataloguing and reference services, we

decided to define a taxonomy intended for the

optimization of multimedia object metadata

classification. A metadata taxonomy must support

different organizations that manage the digital

contents in various ways. This taxonomy aims to

create a shared language that helps to lower the

existing barriers between systems and people, so

increasing knowledge retrievability and usability.

Information are often application-centric;

departments and processes are often fragmented. We

want to identify these differences and leverage them

through a cross-mapping between different

vocabularies.

The basic starting concept is the definition of a

KB: in our study, the knowledge base is composed by

all kinds of multimedia objects that a digital library

must manage: ebooks, audiobooks, music, websites,

magazines, images.

We have first analyzed the metadata standards

DATA2015-4thInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

242

used in multimedia content management, and then

defined a taxonomy to represent the semantics of the

multimedia content, finally giving an unambiguous

meaning to each metadata.

4.1 The First Phase: Selected

Metadata, UGC and Direct

Mapping

We used the metadata standards that have been

described Section 2 to have a complete modelling of

the domain of multimedia content properties. Then

we compare these metadata standards with metadata

schemas used for user-generated content. We use this

approach because such standards allow for

cataloguing different aspects of multimedia content.

4.1.1 Selected Metadata

Metadata belonging to the Dublin Core standard are

entirely adopted, since they can represent any type of

digital resource, due to the generality of the elements

semantics. The adoption of the DC standard allows

for the system to be OAI compliant, so that the OAI-

PMH protocol could be used. The XMP standard is

vast, and requires a selection, not only of its schemas,

but also of the metadata included in them. Unlike DC,

XMP represents very specific information, which are

not entirely of interest for the digital library context.

The metadata that are considered are thus the ones

belonging to the following schemas: XMP basic

schema, XMP rights management schema, XMP

paged-text schema, XMP Dynamic Media Schema

and Exif schema. Among those, only metadata

belonging to XMP rights management schema were

taken entirely, as they represent information about the

rights associated to the resource. It was also decided

to include metadata taken from MAG 2.0, an

application profile specifically designed for the

description of digital resources (derived or born

digital). MAG includes structural and administrative

metadata, but does not include a vast set of

descriptive metadata (it only includes the 15 core

elements of DC). This section must be in one column.

4.1.2 User-Generated Content

The cultural information also exists outside of the

institutions that manage the collection of books. One

of our activities involved studying the representation

of User-Generated Content (UGC) (Pani et al., 2014).

YouTube for instance was studied in order to gather

the metadata used for multimedia content, especially

video content; we noticed how it makes use of

different standards (Atom Publishing Protocol,

GeoRSS) as well as proprietary ones (YouTube XML

Schema). YouTube uses feeds, based on XML files,

each of which has its own metadata containing

objects and a web link to the source of the content.

XML schemas used by Youtube are many (Atom

Syndication, Format Open Search, Media RSS

Schema, YouTube XML, Google Data Schema,

Schema GeoRSS, Geography, Markup Language,

Atom Publishing, Protocol Google Data API, Batch

Processing). This large amount determines the use of

a very high number of metadata. Once the metadata

coming from YouTube had been grouped, the

semantics of each and every one of them was

evaluated, and, similarly to what was done for DC and

XMP, only the most representative and interesting

metadata for a digital library were selected.

4.1.3 Direct Mapping

Our next step was the direct mapping between

metadata: same meaning, same format, and same data

type. We represented their correspondences in a table,

so that we could have a clear view of both the

metadata we considered in this first phase as a whole,

and of the way in which the semantics of the elements

overlap. We then chose, where semantics overlapped,

the most suited for our purposes. In the table, direct

semantic correspondence is represented by placing

metadata in the same row, whereas isolated metadata

represent a single semantics. The XMP standard was

not compared in the table because none of its

elements have the same semantics as any of the

metadata shown above.

4.2 The Second Phase: Data Collection,

Grouping, Selection

From the raw data we went up to assign them to more

general categories up to the root node. We analyzed

the specific objects of digital libraries context,

choosing the tags that we considered as the most

suitable for the realization of the taxonomy. The tags

were then identified as labels that constitute the set of

descriptive metadata of a resource. We then searched

for the necessary information to retrieve objects in the

domain. This analysis is divided into 3 steps: data

collection, grouping, and selection. Data collection

has the sole aim to search for multimedia objects (in

reference sites) constituting the reference domain,

analyzing and writing down the characteristics (i.e.,

tags) they possess. Grouping involves assigning the

labels collected in the first phase to different

categories. Lastly, selection consists in choosing tags

AModelforDigitalContentManagement

243

that are considered to be the most suitable candidates

for representation. The frequency with which the

characteristics are shown in reference sites, and the

possible interest that a digital library might have in

considering them, are some of the factors taken into

account when making the choice.

The websites that were used as reference are:

Europeana, Internet Culturale, Cultura Italia, Internet

Archive, Open Library, and Project Gutenberg. These

websites offer an overview of the objects that a digital

library is interested in representing, making it

possible to examine and compare the classification of

those same objects found in portals. The first step was

to list the different types of analysed objects, based

on the name assigned to them by the website. Each

type of element is associated to one of the following

macro-categories: “Image”, “Text”, “Audio”,

“Video”, “Ebook”, “Other”. The macro-category

“Other” groups together metadata belonging to

elements that do not belong to the other labels (such

as metadata belonging to the legal documents group

from the previous sections). Once the nature of the

elements was defined, each group of metadata

describing an element becomes part of the group of

metadata belonging to the nature of that same

element. The importance of this phase is in

understanding how objects are classified and which

information were chosen to represent them. A list of

tags, divided by macro-category, is indeed

appropriate, but after that it is useful to create a list of

tags that uses their semantics to distinguish them,

regardless of their name. In order to avoid duplicates,

a name that reminds of the semantics of that tag is

assigned, while the choice of the most suitable name

is postponed to a later phase. With a list of metadata

by macro-categories, all we had to do was to decide

which tags to keep and which ones to reject,

considering the frequency of their use on the chosen

websites and the importance of each piece of

information for a digital library.

4.3 Refining Phase

This phase involved comparing metadata taken from

the standards analysed during the first phase with the

data collected during the second phase. The purpose

of the comparison was to verify whether all the

characteristics studied during the second phase were

represented by the metadata retrieved during the first

phase. If they were not, new metadata would be

created, either as an extension of the chosen metadata

(DC allows semantics extensions by adding

qualifiers) or as entirely new metadata, creating a new

namespace to include them. The process began with

a mapping phase, followed by the creation of new

metadata. Once the refining phase was completed,

and all available metadata were selected, we started

to design the taxonomy schema.

The first step was to compare the list of tags with

the metadata selected during the previous two phases,

based on their semantics. Thus, tags whose semantics

was not covered by any metadata were identified,

with the aim of creating new metadata specifically

designed for them. Tags with semantics similar to DC

elements, but more precise, were described via new

qualifiers, while tags that could not be encompassed

by the DC standard would be included in a new

namespace called “multimediatype”. For example,

the following new qualifiers were created for the DC

element “dc.identifier”: “isbn”, “LoC”, “dewey”,

“iccd”, where each of them represent a specific code

associated to the digital resource. It is not required to

create one metadata for each code type, but it was

considered wiser to create four qualifiers of

“dc.identifier” for the most relevant codes: ISBN,

LoC, dewey, iccd. For the other codes, the general

“dc.identifier” can be used, and the type of code has

to be specified during insertion. The namespace

“multimediatype”, instead, includes metadata

describing federal documents, publishing

information, institutions (for example, museums and

libraries), and User-Generated Content. After

creating the metadata derived from the second phase,

the capability of any metadata to represent

fundamental concepts needed to be investigated. The

fundamental concepts are, for example, the ebooks

categorization, the definition of “grey literature”

documents, UGCs, and rights management. The

results of our research showed that there were not any

metadata suitable for suggesting the optimal software

or hardware device for the exploitation of a resource,

e.g. an ebook. To overcome this, two new DC

qualifiers were created: “dc.format.testedSoftware”

and “dc.format.testedDevice”. These metadata define

the most suitable software and device through which

the resource can be exploited. Grey literature can be

defined by the level of education of their target users

(thus defining the suggested group of users that

typically use a specific kind of resources), and the

type of document, selected from a list of types

belonging to that category (for example, papers,

theses and scientific research documents). The

metadata are: “dc.audience.instructionLevel” and

“multimediatype.documentCategory”.

The integration of UGC metadata was performed

by focusing on those that featured a single semantics

during the first phase, and selecting the most suited

metadata for the context.

DATA2015-4thInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

244

Under “multimediatype.ugc”, metadata “mail”,

“mediarestriction”, “private”, “error”, “statistics”

were created, for representing information about the

user who provided the resource (“mail”), information

about viewing restrictions (some resources can only

be viewed in some countries), and to qualify the

resource status (e.g., if it is private, only users allowed

by the owner can view it), and also information about

errors and statistics (such as the average rating or the

number of views).

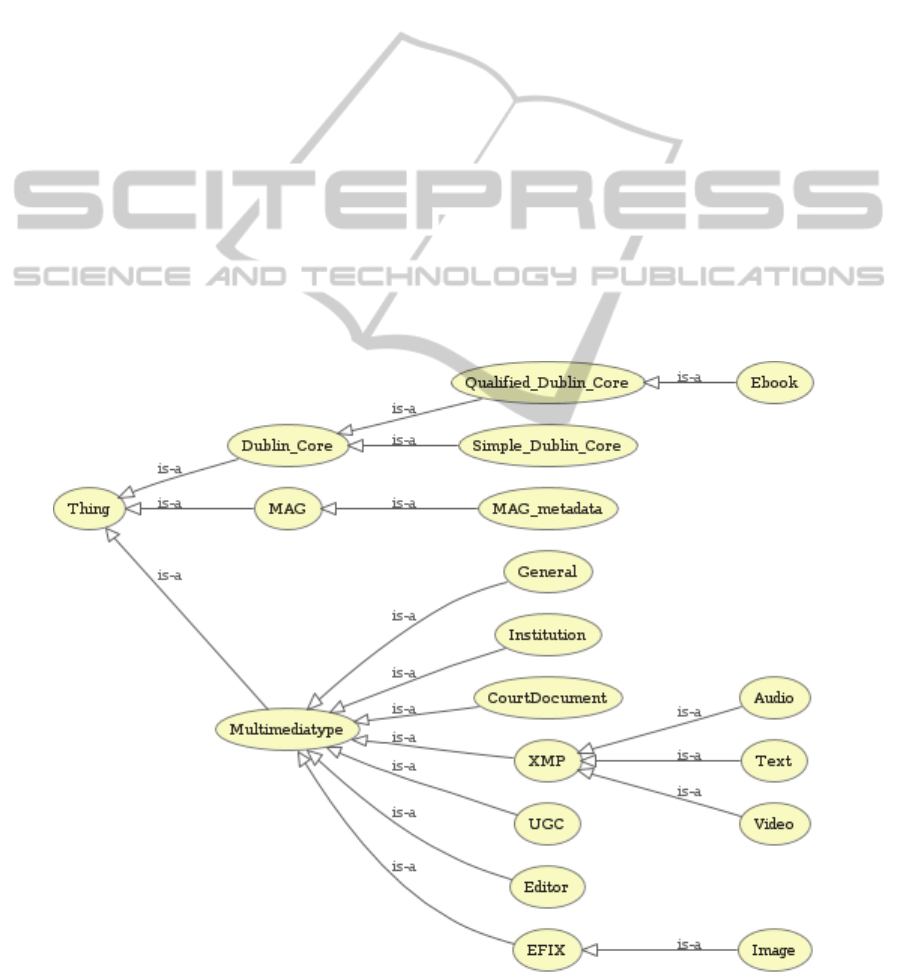

The resulting metadata were used to create the

taxonomy structure. The structure has three branches

departing from the parent node, related to the main

groups of metadata: MAG, DC, multimediatype.

MAG is an application profile with its own structure,

so it does not need to be changed and it could be

entirely included in the taxonomy. The DC, being

composed of simple elements and qualifiers, suggests

a further distinction in two levels: the first is reserved

to simple elements that come directly from the

namespace “dc”, the second to the qualifiers of the

aforementioned elements, among which, the class

“Ebook”, that comprises “testedSoftware” and

“testedDevice” metadata. Those metadata, in fact,

refer only to that type of resource. Multimediatype

metadata can be associated to different types of

resource with no distinction (those in the “general”

category), or to a specific resource. Among those, we

include XMP, that consists of the subclasses Audio,

Text and Video, and Exif, which includes the Image

subclass. This hierarchy makes it possible to quickly

point out the nature of a resource and the position of

the related metadata in the taxonomy, at the moment

in which a resource has to be catalogued, thus

allowing for easily selecting the level of detail, or

which standard to use.

As previously discussed, we found it necessary to

introduce two fundamental metadata that final users

should consider in accessing the resource. These two

metadata are dc.format.testedSoftware and

dc.format.testedDevice: the former suggests an

application that might be used to easily access the

resource, along with some additional information

about the operating systems that are compatible with

the suggested application; the latter gives some

information about the devices which might be used to

successfully access the resource (e.g. a specific tablet,

or smartphone).

Taking advantage of the metadata provided in

(Pani et al., 2014), we also selected a set of metadata,

Figure 1: Taxonomy of metadata defined.

AModelforDigitalContentManagement

245

with the purpose of effectively qualifying UGCs in

the context of digital libraries. The selection is a

concise one, since our objective is to provide a core

metadata set for UGCs. They could easily adapt to the

specific needs of a given library.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We studied a process to identify existing

formalizations and knowledge sources within the

domain of digital libraries, focusing our attention to

multimedia objects. Valuable knowledge was

represented in explicit form through proper

information formalization and codification, with the

aim of increasing knowledge availability through

enhancing interoperability. Our real goal is to make

interesting knowledge available for sharing and reuse.

In order to do this, we focused on interesting

information in domain-specific knowledge, thus

allowing for the formalization of metadata associated

with multimedia objects.

The resulting taxonomy, created on the basis of an

accurate analysis and the exploitation of widespread

standards, provides a descriptive model for the

content management in the context of Italian digital

libraries. In particular, resources such as ebooks,

which have recently become more popular, need not

only an exhaustive description (i.e, proper descriptive

metadata), but also metadata that make them easy to

use. The classification structure proposed in this

paper is thus able to provide information that is

currently essential, because it is impossible to have a

full understanding of the knowledge level of each and

every final user. Metadata that describe the most

suitable software for the effective use of a certain

resource, or that provide information on the most

suitable device for offering the best user experience

for that resource, were introduced, as we considered

those information to be of primary relevance for the

modern digital libraries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Simone Porru gratefully acknowledges Sardinia

Regional Government for the financial support of his

PhD scholarship (P.O.R. Sardegna F.S.E. Operational

Programme of the Autonomous Region of Sardinia,

European Social Fund 2007-2013 Axis IV Human

Resources, Objective l.3, Line of Activity l.3.1).

REFERENCES

Adobe XMP Specifications and Additional

Properties,http://www.adobe.com/content/dam/Adobe/

en/devnet/xmp/pdfs/XMPSpecificationPart2.pdf

Arndt, R., Troncy, R., Staab, S., Hardman, L., Vacura, M.,

2007. COMM: designing a well-founded multimedia

ontology for the web. In The semantic web, Springer

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 30-43.

Bellahsene, Z., Bonifati, A., & Rahm, E., 2011. Schema

matching and mapping (Vol. 20). Heidelberg (DE):

Springer.

Buonazia, I., Masci, M. E., Merlitti, D., 2007. The Project

of the Italian Culture Portal and its Development. A

Case Study: Designing a Dublin Core Application

Profile for Interoperability and Open Distribution of

Cultural Contents. In Proceedings ELPUB 2007

Conference on Electronic Publishing, pp. 393-

404.http://elpub.scix.net/data/works/att/114_elpub200

7.content.pdf

Caffo, R., 2013. Global interoperability and linked data in

libraries: ICCU international commitment. In JLIS.it,

Italian Journal of Library, Archives, and Information

Science, Vol. 4, Issue 1, 99. 17-20.

Cultura Italia, http://www.culturaitalia.it/

Dasiopoulou, S., Tzouvaras, V., Kompatsiaris, I., Strintzis,

M. G., 2010. Enquiring MPEG-7 based Ontologies. In

Multimedia Tools and Applications, Vol. 46, Issue 2,

pp. 331-370.

Davis, D. M., 2004. NISO Standard Z39.7 - The Evolution

to a Data Dictionary for Library Metrics and

Assessment Methods. In Serials Review, Vol. 30,

Issue1, p. 15.

DCMI Metadata Terms - Dublin Core® Metadata Initiative,

http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/

Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, 2014.

http://www.dublincore.org

Europeana, http://www.europeana.eu/

García, R., Celma, O., 2005. Semantic Integration and

Retrieval of Multimedia Metadata. In Proceedings of

the 5th International Workshop on Knowledge Markup

and Semantic Annotation, pp. 69-80

Gartner, R., 2002. METS: Metadata Encoding and

Transmission Standard. JISC Techwatch report TSW.

Google Developers, https://developers.google.com/

youtube/2.0/reference

Hill, L. L., Janee, G., Dolin, R., Frew, J., Larsgaard, M.,

1999. Collection metadata solutions for digital library

applications. In Journal of the American Society for

Information Science (JASIS), 50(13), pp. 1169-1181.

Vol. 50, Issue 13.

Hunter, J., 2001. Adding Multimedia to the Semantic Web

- Building an MPEG-7 Ontology. In Proceedings of the

International Semantic Web Working Symposium

(SWWS).

Hunter, J., 2003. Enhancing the semantic interoperability of

multimedia through a core ontology. In IEEE

Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video

Technology, pp. 49-58.

ICCU, http://www.iccu.sbn.it/

DATA2015-4thInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

246

IFLA, 1998. Functional requirements for bibliographic

records: final report / IFLA Study Group on the

Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records.,

ISBN 978-3-598-11382-6, www.ifla.org/files/assets/

cataloguing/frbr/frbr.pdf

Internet Archive, https://archive.org

Internet Culturale, http://www.internetculturale.it/

Jérôme Euzenat, Pavel Shvaiko, 2013. Ontology Matching

- Second edition Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg

(DE).

Lagoze, C., Van de Sompel, 2003. The Making of the Open

Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting.

In Library Hi Tech, Vol. 21, Issue 2, pp. 118-128.

Open Library, https://openlibrary.org/

Pani F. E., Concas G., Porru S., 2014. An Approach to

Multimedia Content Management. In Proceedings of

the 6th International Conference on Knowledge

Engineering and Ontology Development, KEOD 2014.

ISBN: 978-989-758-049-9.

Pierazzo, E., 2006. Metadati Amministrativi e Gestionali:

Manuale Utente. Ed. Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo

Unico delle Biblioteche Italiane e per le Informazioni

Bibliografiche.

Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/

Rühle, S., Schulze, F., Büchner, M., 2014. Applying a

linked data compliant model: The usage of the

Europeana Data Model by the Deutsche

DigitaleBibliothek. In International Conference on

Dublin Core and Metadata Applications.

Scherp, A., Eißing, D., Saathoff, C. 2012. A method for

integrating multimedia metadata standards and

metadata formats with the multimedia metadata

ontology. In International Journal of Semantic

Computing, Vol. 6, Issue 1, pp. 25-49.

Schwartz, C., 2000. Digital libraries: an overview. In The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, Vol. 26, Issue 6,

pp. 385-393.

Stadlhofer, B., Salhofer, P., Durlacher, A., 2013. An

Overview of Ontology Engineering Methodologies in

the Context of Public Administration. In Proceedings

of the 7th International Conference on Advances in

Semantic Processing, pp. 36-42.

Suárez-Figueroa, M. C., Atemezing, G. A., Corcho, O.,

2013. The landscape of multimedia ontologies in the

last decade. In Multimedia tools and applications, Vol.

62, Issue 2, pp. 377-399.

Technical Standardization Committee on AV & IT Storage

Systems and Equipment, 2002. Exchangeable image

file format for digital still cameras: Exif version 2.2.

Published by: Standard of JEITA (Japan Electronics

and Information Technology Industries Association).

http://www.exiv2.org/Exif2-2.PDF

The Metadata Working Group, http://www.

metadataworkinggroup.org/

Tsinaraki, C., Polydoros, P., Christodoulakis, S., 2004.

Interoperability Support for Ontology-based Video

Retrieval Applications. In Proceedings of the 3rd

International Conference on Image and Video

Retrieval, pp. 582–591.

AModelforDigitalContentManagement

247