A Model of Effective IT Governance for Collaborative Networked

Organizations

Morooj Safdar

1

, Greg Richards

2

and Bijan Raahemi

2

1

Faculty of Engineering, University of Ottawa, Laurier Ave., Ottawa, Canada

2

Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, Laurier Ave., Ottawa, Canada

Keywords: IT Governance, IT Governance Framework, Collaboration, Collaborative Networks, Collaborative

Networked Organizations.

Abstract: Inter-organizational collaboration based on the use of IT systems is now essential for organizations working

as Collaborative Networked Organizations (CNOs). However, little research has been done to examine the

critical success factors involved in shared IT governance among members of a CNO. Accordingly, this

research develops a model of inter-organizational IT governance composed of critical success factors

(CSFs) and key performance indicators (KPIs). The study defines fourteen CSFs that are classified under

the main four categories of IT governance, which include strategic alignment, resource management, value

delivery and risk management, and performance measurement. The main dimensions of the KPIs include

consensus, alignment, accountability, trust, involvement and transparency. To validate the research model,

we conduct a case study of a healthcare CNO by gathering insights from CNO participants on the

importance of the proposed CSFs and performance indicators included. The findings of the research validate

the importance of the CSFs but suggest that they could be ranked in order of criticality. In addition, certain

CSFs were redefined based on the experience of CNO participants and questions were raised related to the

context of the CNO, which influences participant perceptions, as well as to the degree of formalization

noted in the CNO.

1 INTRODUCTION

A vast number of organizations are adopting

different forms of alliances or corporate structures to

manage their processes, gain a competitive

advantage, and collaborate efficiently with inter-

organizational entities (Prasad, Green, and Heales,

2012). In these alliances, several corporate structures

operate in different geographical locations, which

increases the number of virtual organizations or

collaborative organizational structures “COSs”.

These structures adopt and use different IT resources

in order to maintain a successful level of

collaboration. Moreover, the emergence of dynamic

IT technologies, specifically web 2.0 tools, has a

significant effect on the formation of alliance

structures that depend on the creation of IT

governance models (Prasad, Green, and Heales,

2012). Accordingly, the number of IT projects

undertaken by organizations has grown

exponentially in recent years. Unfortunately, a large

number of these projects fail, whether being

conducted within or between organizations (Weill

and Woodham, 2002). These failures could be

related to incomplete or poorly executed IT projects,

the complexity of the nature of IT technologies and

tools (Ko and Fink, 2010), or ineffective governance

or use of IT systems (Weill and Woodham, 2002).

Therefore, collaborative-networked organizations

“CNOs” should not only try to exploit the shared IT

resources effectively but also maintain and adopt

effective governance models to increase their

chances of success.

2 BACKGROUND

The mainstream research on IT governance tends to

emphasize the single organization as the unit of

analysis (Ali and Green, 2009; Huang et al., 2010;

Willson and Pollard, 2009). In the area of IT

governance and considering CSFs as essential

elements for its effective implementation, few CSF

studies have been undertaken, although IT

governance has become critical to most

organizations today (Rusu and Nufuka, 2011).

191

Safdar M., Richards G. and Raahemi B..

A Model of Effective IT Governance for Collaborative Networked Organizations.

DOI: 10.5220/0005537401910202

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2015), pages 191-202

ISBN: 978-989-758-113-7

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Although studies on best practices and success

factors of IT governance exist, they target a single

organization as a unit of analysis (Ferguson et al.,

2013; Ko and Fink, 2010; Rusu and Nufuka, 2011;

Weill and Ross, 2004; Weill and Woodham, 2002).

There are also studies that prove the importance of

collaborative network IT governance and the

business value of IT to the network (Camarinha-

Matos et al., 2009; Rabelo and Gusmeroli, 2006;

Prasad, Green, and Heales, 2012; Haes and

Grembergen, 2005; Melville, Kraemer, and

Gurbaxani, 2004), but these do not define CSFs or

KPIs to measure its effectiveness.

The success factors proposed in Rusu and

Nufuka (2011) and other studies (Guldentops, 2004;

A.T. Kearney, 2008; Weill and Woodham, 2002;

Ferguson , Green, Vaswani, and Wu, 2013) of

traditional organizations with effective IT

governance may not necessarily apply to situations

of inter-organizational collaboration. In this context,

there is always a conflict of knowing who is

responsible for handling the IT governance practices

for the CNO and how the CNO will assess and test

the effectiveness of adopting such a form of network

governance (Provan and Kenis, 2007).

Accordingly, this research focuses on defining a

model for effective IT governance for CNOs that

includes CSFs and assigned KPIs to help the

collaborative achieve success in collaboration and in

controlling the shared IT assets.

3 THE PROPOSED MODEL OF

EFFECTIVE IT GOVERNANCE

FOR CNO

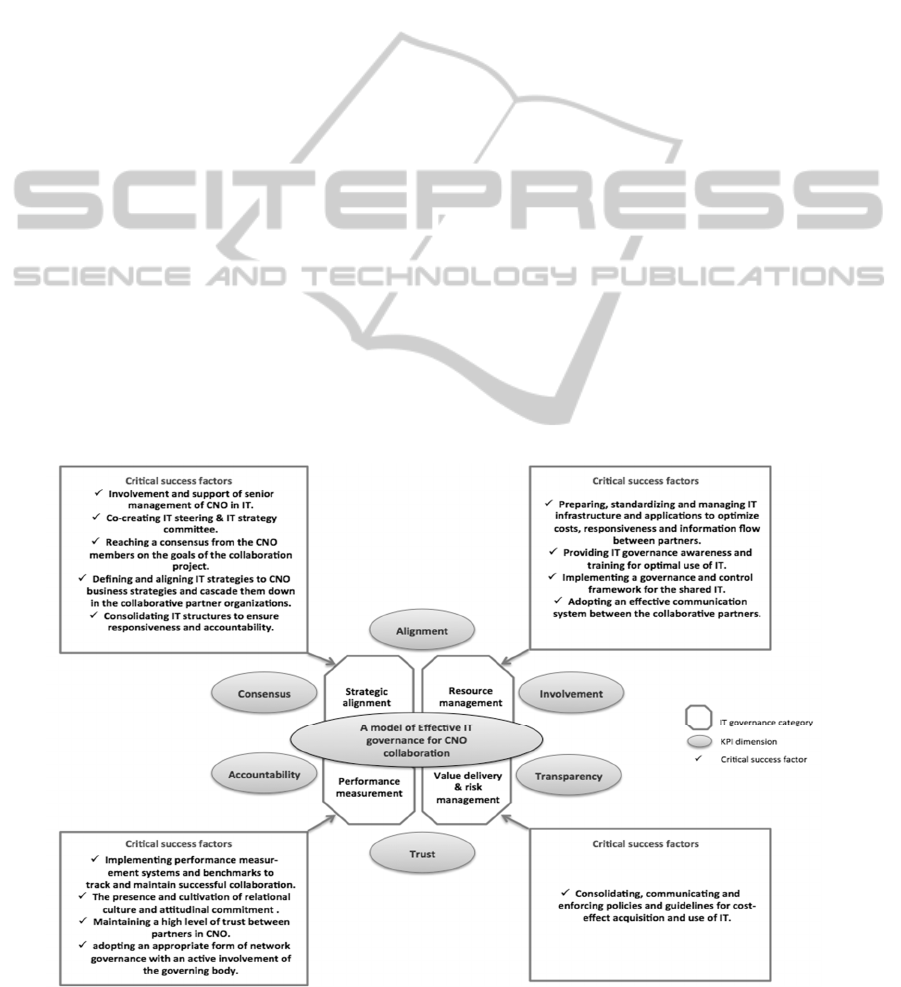

The proposed model targets the strategic level of the

collaborative-networked organization. The model

consists of critical success factors represented in the

squares in Figure 1 and key performance indicators

that measure the CSFs represented in shaded circles.

The model is designed based on the four main

categories of IT governance represented in the

rectangles at the edges of Figure 1: strategic

alignment, resource management, performance

measurement, and value delivery and risk

management. Each category of IT governance has

critical success factors assigned to it. The key

performance indicators are categorized into 6

dimensions, which are alignment, consensus,

accountability, trust, transparency and involvement,

assess the effectiveness of the CSFs.

3.1 Critical Success Factors for CNO

Effective IT Governance

Critical success factors define the most important

management-oriented implementation guidelines to

achieve control over and within its IT processes

(ITGI and OGC, 2005). Focusing on the CSFs will

Figure 1: A model of effective IT governance for CNOs.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

192

identify the most vital processes that directly

influence the organization’s performance

(Shivashankarappa, Dharmalingam, Smalov, and

Anbazhagan, 2012). The proposed model of

effective CNO IT governance is depicted in Figure

1.

The KPI dimensions of CNO effective IT

governance and their assigned critical success

factors are discussed in more detail in the following

section.

3.1.1 Consensus: Reaching a Consensus

from the CNO Members on the Goals

of the Collaborative Project

Consensus on goals and “domain similarity” allows

organizational participants to collaborate better than

when there is conflict, although conflict can also be

a stimulant for innovation. Van de Ven (1976)

argued that when there is general consensus on

broad network-level goals, both regarding goal

content and process, and in the absence of hierarchy,

network members are more likely to be involved and

devoted to the network and more likely to work

together (cited in Provan and Kenis, (2007)). There

may be significant differences across networks and

network members regarding agreement on network-

level goals and the extent to which organizational

goals can be achieved through network involvement.

Although high goal consensus is, apparently, an

advantage in building network-level commitment,

networks can still be somewhat effective with only

moderate levels of goal consensus (Provan and

Kenis, 2007), since the goal of the shared project is

not necessarily the goal of all participants (Tapia et

al., 2008).

3.1.2 Alignment: Defining and Aligning IT

Strategies to CNO Business Strategies

and Cascading Them down in the

Collaborative Partner Organizations

Building a strong relationship between senior IT

managers and senior business managers to support

both their strategies and day-to-day operations is

fundamental for organizations to achieve effective

IT governance. Managers need to identify key goals

across IT to help support business strategies

(Richards, 2006). A very influential tactic to build

and then strengthen such informal relationships is by

collaboratively involving the targeted individuals in

formal decision processes related to IT governance

(Huang, Zmud, and Price, 2010).

It is the responsibility of each collaborative

organization representative in the IT steering

committee to cascade both strategies and IT

governance practices to the operational level of their

individual organizations. In a network of

organizations, IT governance is required at several

levels. Organizations with different IT needs in

divisions, business units, or geographies require a

separate but connected layer of IT governance for

each entity. Connecting the governance arrangement

matrices for the multiple levels in an organization

makes explicit the connections, common

mechanisms, and pressure points (Weill, 2004).

3.1.3 Adopting an Appropriate Form of

Network Governance with the Active

Involvement of the Governing Body

To attain successful collaboration within a network,

a CNO must make sure to choose the most suitable

governance form or structure (Provan and Kenis,

2007), and more effective collaborative IT

governance is associated with the active

involvement of a governing body (Chong and Tan,

2012). Chong and Tan (2012) state that it is

imperative to assign a governing body to regulate

and monitor the committees such as IT strategy and

IT steering committees. Network governance forms

can be categorized according to two distinctions;

whether the form is brokered or not, and whether the

brokered network is a participant or is externally

governed. Each form has certain basic structural

characteristics and is applied in practice for a variety

of reasons; accordingly, no one model is inherently

superior or effective. Rather, each form has its own

specific strengths and weaknesses leading to

outcomes that are likely to depend on the form

chosen (Provan and Kenis, 2007).

3.1.4 Involvement and Support of CNO

Senior Management in IT

Senior management support for IT is considered to

be the most important enabler of business and IT

alignment (Ferguson, Green, Vaswani, and Wu,

2013), and crucial to effective IT governance

(Huang, Zmud, and Price, 2010). This practice refers

to an organization’s senior executives’ personal

engagement and support in IT-related decision

making such as investments and monitoring

processes. This involvement finds participating

senior managers and executives interacting with one

another to outline and discuss IT-related issues; it

occurs through formal and informal pathways.

Formally, the senior managers of each partner

AModelofEffectiveITGovernanceforCollaborativeNetworkedOrganizations

193

organization cooperate and interact through their

participation on established IT governance bodies,

such as IT steering committees, that shape and direct

IT-related strategies, policies and actions.

Informally, these senior managers interact while

carrying out their day-to-day work responsibilities

(Chan, 2002). Huang et al. (2010) found that the

performance of IT tends to be better with both the

formal (through steering committees) and informal

(through personal interactions) involvement of IT

and business senior managers in IT-related decision

making processes than with informal involvement

alone.

3.1.5 Accountability: Co-creating IT

Steering and IT Strategy Committees

A governance practice considered fundamental for

effective IT governance and the alignment of IT-

related decisions and actions with an organization’s

strategic and operational priorities is the IT steering

committee, which is a body comprised of senior

executives/managers convened to administer and

coordinate IT-related activities. The IT steering

committee is a formal body that includes

representation from both business and IT executives

who regularly meet to address specific IT-related

issues, and whose interaction during these

deliberations ensure that the various represented

interests and perspectives are heard (Huang, Zmud,

and Price, 2010; Ferguson, Green, Vaswani, and

Wu, 2013). An IT steering committee in the case of

a collaborative-networked organization is co-created

and involves representatives from each of the CNO

constituents. The co-created IT steering committee

functions as a ‘board of directors’, which involves

IT/business executives, managers, and professionals

holding differing vested interests and perspectives

for specific domains of IT-related activities in

setting CNO-wide policies and procedures,

allocating resources, and monitoring the

performance of the shared IT resources.

3.1.6 Consolidating IT Structures to Ensure

Responsiveness and Accountability

The IT governance structure deals with the decision-

making structures and the responsible

committees/functions adopted for IT-related

decisions (Brown and Grant, 2005). This practice is

vital to ensure responsiveness and accountability,

and positively enhances IT governance performance

(Rusu and Nufuka, 2011). The three most prevalent

governance structures are centralized, decentralized,

and hybrid “federal” structures (Brown and Grant,

2005). With centralized governance structures, IT

decisions follow a top-down, enterprise-wide

perspective, while with decentralized governance

structures, IT decisions reflect a bottom-up, local

work unit perspective. Although the centralized and

decentralized governance structures by definition are

mutually exclusive, an organization’s important IT

decisions can also be orchestrated through a third

sort of governance structure, which is the hybrid

structure or the federal mode. Hybrid governance

structures may indicate a variety of alternative

structures, most typically: collaboratively engaging

participants holding enterprise-wide perspectives

with participants holding local perspectives,

simultaneously using centralized governance

structures for some IT decisions and decentralized

governance structures for other IT decisions, or

applying both of these designs. For each type of

governance structure there are distinct advantages

and disadvantages.

3.1.7 Implementing a Governance and

Control Framework for the Shared IT

Applying a governance framework to control the

shared IT assets is considered essential to successful

IT governance. One of the most commonly used

governance reference frameworks, which is the

choice of many regulators and commentaries, is the

Control Objectives for Information and related

Technology (COBIT). COBIT is well accepted by

many enterprises; it is mainly introduced by the

audit function as the auditors’ framework for

judging control over IT, and IT groups have picked

it up, often because it provides for performance

measurement. COBIT offers the foundation and the

tool set to analyze, based on the enterprise value and

risk drivers, where the enterprise is relative to IT

governance, and where it needs to be (Guldentops,

CISA, and CISM, 2004).

3.1.8 Implementing Performance

Measurement Systems and

Benchmarks to Track and Maintain

Successful Collaboration

Measuring the performance of the partners’

collaboration is essential to managing collaborative

networks in general (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2008)

and to achieving effective IT governance (Rusu and

Nufuka, 2011). In collaborative environments, inter-

organizational Performance Indicators (PIs) must be

addressed, as well as intra-organizational ones, in

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

194

order to fully cover the performance of the alliance

(Kamali, 2013). The use of a performance

measurement system incorporating a set of metrics

provides management with an accurate view of IT

operations performance and assists them with a

means to help improve governance and

accountability for many stakeholders (Ferguson ,

Green, Vaswani, and Wu, 2013). The most

widespread performance management system, since

the mid-1990s, is the balanced scorecard (BSC). It

allows organizations to follow-up with and assess

their strategies. The use of the BSC as a

performance measurement system for IT operations

is reinforced by agency theory as a mechanism to

reduce agency losses by more efficiently monitoring

the IT operations. Advocates of the balanced IT

scorecard recommend that the benefits of such a

system go beyond the traditional financial

assessment methods and extend them to include

measures relating to customer satisfaction, internal

processes, expertise of IT staff, and the ability to

innovate; these measures may be compared with

benchmarking figures (Ferguson , Green, Vaswani,

and Wu, 2013).

3.1.9 Trust: Maintaining a High Level of

Trust between the CNO Members

Trust has been identified as key to IT governance

(Richards, 2006). In the general network literature, it

has frequently been considered as critical for

network performance and sustainability (Provan and

Kenis, 2007). Trust in collaborative networks has

been defined as ‘‘the willingness to accept

vulnerability based on positive expectations about

another’s intentions or behaviors’’ (McEvily,

Perrone, and Zaheer, 2003, 92). Proven and Kenis

(2007) argue that to understand network-level

collaboration the dissemination of trust is critical, as

is the degree to which trust is reciprocated among

network members. In addition, it is not only that

trust is considered a network-level concept but also

that network governance must be consistent with the

general level of trust density that occurs across the

network as a whole.

3.1.10 The Presence and Cultivation of

Relational Culture and Attitudinal

Commitment

Chong and Tan (2012) indicate that more effective

collaborative IT governance is associated with a

coordinated communication process and the

presence of relational culture and attitudinal

commitment. As a collaborative network consists of

several organizations, a relational organizational

culture is crucial to managing the interactions

required for IT governance implementation and to

deliver a shared understanding between IT and

business people. Organizational culture plays a

significant role in influencing collaborative

behavior, and a strong organizational culture can

enhance the co-ordination processes, support

consistent decision-making processes, and increase

the level of attitudinal commitment. The extent to

which the organizational cultures differ in a

collaborative network is known as cultural distance;

a wider cultural distance will result in lower levels

of integration and cohesion (Shachaf, 2008).

Accordingly, it will lead to inefficient flows of

information and a constrained communication

process within the network, which in turn will affect

the collaborative relationships. Hence, it is critical

for a collaborative network to promote and cultivate

a relational organizational culture that unifies

subculture beliefs and practices within the network.

The attitudinal commitment refers to an

emotional or affective component that is driven by

the feelings and attitudes of the participants to the

specific relation. It is more appropriate for the

committee members to possess attitudinal

commitment, as they would allocate most of their

time to controlling and managing their functional

roles (Chong and Tan, 2012).

3.1.11 Transparency: Adopting an Effective

Communication System between

Collaborative Partners

One of the practices of effective IT governance is

ensuring that the deliberations of the governance

bodies and IT steering committees are well

disseminated, communicated, and accessed by all

appropriate members (Huang, Zmud, and Price,

2010). Making each IT governance mechanism

transparent to all managers is considered a critical

success factor of IT governance. The more IT

decisions are made secretly and outside of the

governance framework, the less confidence people

will have in the structure and the less willing they

will be to play by the rules, which are designed to

increase enterprise wide performance (Weill, 2004).

Achieving transparency involves the adoption of a

suitable communication system between the partner

organizations and the members, facilitating the

collaboration process. The communication system is

essential for disseminating rules and polices across

the CNO. The type and nature of communication

AModelofEffectiveITGovernanceforCollaborativeNetworkedOrganizations

195

system adopted depends on the size of the

organization and its number of partners. In some

situations, it could be very simple, for example with

the use of emails, or very complex with the

establishment of a shared platform. A larger number

of communication channels results in a more

efficient use of IT and a greater breadth of IT use.

Having Intranet as the only organizational

communication channel would not necessarily

enable better communication of IT governance

processes and decisions. Rather, it requires more

communication channels to integrate and

disseminate information, enabling a wider degree of

IT governance transparency, and a shared

understanding between business and IT can be

established (Weill and Ross, 2004). Coordinated

synchronous and asynchronous communication

channels would play an important role in facilitating

the collaborative network’s processes (Chong and

Tan, 2012).

3.1.12 Preparing, Standardizing, and

Managing IT Infrastructure and

Applications to Optimize Costs,

Responsiveness, and Information

Flow between Partners

Organizations in the collaborative network must be

ready and prepared in advance with the needed IT

applications to successfully communicate with

partners and commence the collaboration project

(Rabelo and Gusmeroli, 2006). The IT preparation

includes compliance with a common interoperable

infrastructure, the adoption of common operating

rules, and a common collaboration agreement,

among others. Peterson (2004) also suggested that

the practice of preparing, standardizing and

managing IT infrastructure would help produce

reliable and cost-effective infrastructure and IT

applications (cited in Rusu and Nufuka, 2011).

3.1.13 Providing IT Governance Awareness

and Training for Optimal Use of IT

Ensuring that knowledge about IT and its

governance are available to the collaborative

organizations is crucial and acts as a stepping-stone

to achieving effective IT governance. This practice

is important for innovation and to optimize IT

capabilities and governance (Rusu and Nufuka,

2011). Education to help managers understand and

use IT governance mechanisms is critical. Educated

users of governance mechanisms suggest that

committee members are more likely to be

accountable for the decisions they make and less

likely to second-guess other decisions (Weill, 2004).

3.1.14 Consolidating, Communicating, and

Enforcing Policies and Guidelines for

the Cost-Effective Acquisition and

Use of IT

This practice is fundamental to effective IT

governance as it introduces and enforces best

practices and clearly informs the organization as a

whole about the processes, methods, and framework

to which it needs to adhere, hence encouraging

desirable behaviours and optimal IT value creation

and preservation (Rusu and Nufuka, 2011). Besides,

Huang et al. (2010) state that the manner by which

IT-related policies, guidelines, and procedures are

clearly communicated to employees and

disseminated across an organization is considered

significant to efficient IT deployment and effective

IT governance.

In order to have a common understanding of

applicable IT-related actions to frame the

interactions of individuals involved in IT-related

activities, it is essential that these policies,

guidelines, and procedures regarding sanctioned IT

behaviors be widely disseminated through an

effective communication system (Uzzi, 1996;

Walker et al., 1997). Compliance with operating

policies, rules, and policies are essential to achieve

successful IT governance. For example, the

enterprise’s security program must be continuously

monitored and evaluated, through internal auditing,

for compliance. In order to effectively implement

security policies to ensure compliance, one must

develop applicable change management strategies

since people are often resistant to change

(Shivashankarappa, Dharmalingam, Smalov, and

Anbazhagan, 2012).

3.2 Key Performance Indicators of

Effective CNO IT Governance

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are the

measurements that represent the enterprise’s critical

success factors for which a balanced scorecard can

be used (Shivashankarappa, Dharmalingam, Smalov,

and Anbazhagan, 2012). Key performance indicators

are lead indicators that define measures of how well

the IT process is performing in enabling the goal to

be reached (ITGI and OGC, 2005).

The key performance indicators for assessing

inter-organizational IT governance are depicted in

Table 1.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

196

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators for Assessing Inter-Organizational IT Governance.

Dimension Code Indicator Description Interpretation

Consensus CO1 Goal Consensus The level of the partners’ agreement on

the CNO stated goals and objectives

“collaborative project goals”.

It can be high, moderately high, or moderately

low (Provan & Kenis, 2007).

Alignment AL1 Understanding of

business by IT

The level of awareness and

understanding of the business

strategies, policies and goals by the IT

staff.

It can be one of the following:

1- IT management not aware

2- Limited IT awareness

3- Senior and mid-management

4- Pushed down through organization

5- Pervasive

AL2 Understanding of

IT by business

The level of awareness and

understanding of the IT strategies,

policies and goals by the business

people.

It can be one of the following:

1- Business management not aware

2- Limited business awareness

3- Emerging business awareness

4- Business aware of potential

5- Pervasive

AL3 Business

perception of IT

value

The level of IT value perceived by

business people.

It can be one of the following:

1- IT perceived as a cost of business

2- IT emerging as an asset

3- IT is seen as an asset

4- IT is part of the business strategy

5- IT-business co-adaptive

AL4 Role of IT in

strategic business

planning

The degree to which IT is involved in

business planning.

It can be one of the following:

1- No seat at the business table

2- Business process enabler

3- Business process driver

4- Business strategy enabler/driver

5- IT-business co-adaptive

AL5 Shared goals,

risks, and

risks/penalties

The degree to which IT is accountable

for shared risks and rewards.

It can be one of the following:

1- IT takes risk with little reward

2- IT takes most of risk with little reward

3- Risk tolerant; IT some reward

4- Risk acceptance and reward shared

5- Risk and rewards shared

AL6 Business strategic

planning

The degree to which business strategic

planning is managed and integrated

across the CNO.

It can be one of the following:

1- Ad-hoc

2- Basic planning at the functional level

3- Some inter-organizational planning

4- Managed across the CNO

5- Integrated across and outside the CNO

AL7 IT strategic

planning

The degree to which IT strategic

planning is managed and integrated

across the CNO.

It can be one of the following:

1- Ad-hoc

2- Functional tactical planning

3- Focused planning, some inter-

organizational

4- Managed across the CNO

5- Integrated across and outside the CNO

(Van Grembergen, 2004)

Trust TR1 Partners trust The density level of trust relations

among collaborative partners.

The density level of trust relations can be low,

high, or moderate (Provan and Kenis, 2007).

Transparency TN1 ICT usefulness

“media channels”

The effectiveness of each of the

communication channels in the shared

system e.g. ICT tools.

A communication channel can be effective,

moderately effective or ineffective.

TN2 Information

accessibility and

availability

The degree to which CNO members

can find and access certain information

using the IT system.

Information can be easily accessible, hardly

accessible, or not available.

Involvement IN1 Senior

management

involvement

The degree to which the senior

managers of a CNO are involved in IT-

related decisions (Huang, Zmud, and

Price, 2010).

Senior managers can be highly involved,

somewhat involved, not involved in decision-

making.

Accountability AC1 Task clarity The clarity level of role definition and

responsibility allocation for CNO

members (De Haes and Van

Grembergen, 2004).

Task clarity can be highly clear, somewhat clear,

or ambiguous.

AModelofEffectiveITGovernanceforCollaborativeNetworkedOrganizations

197

The KPI dimensions related to effective IT

governance for CNOs are:

• Consensus: an agreement between the customer-

facing organization and its direct partners in a

CNO to formulate clear common goals for the

collaborative project (Tapia, Daneva, Eck, and

Wieringa, 2008).

• Alignment: ensuring that IT services support the

requirements of the business, whether such

services are individually or collaboratively

offered (Tapia, Daneva, Eck, and Wieringa,

2008), and ensuring that goals and policies from

both IT and business are supported and aligned.

• Trust: the willingness to accept vulnerability

based on reputation and past interaction

experience (Provan and Kenis, 2007).

• Transparency: the effective dissemination and

accessibility of all information to assigned

individuals in CNOs.

• Involvement: the engagement of firms’ senior

executives in decision-making processes

regarding IT-related issues (Huang, Zmud, and

Price, 2010).

• Accountability: having clear functional roles

and responsibilities assigned to individuals who

are part of the CNO IT steering and IT strategy

committees, or IT structures.

4 A CASE STUDY OF

INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL

IT GOVERNANCE

To validate the proposed model, a case study method

was adopted because this research sought to

understand a real-world phenomenon within its

context (Yin, 2013). Specifically, the study sought to

identify what CSFs determine effective IT

governance for CNO and how a CNO measures its

IT governance effectiveness. A case study method

helps to explore and examine the proposed CNO IT

governance model to gain an in-depth description of

how a CNO operates at the strategic level and how it

governs shared IT resources. The research strategy

undertaken is confirmatory which is based on theory

testing since the model was already developed by

the researcher and then the case study is conducted

to test the usability of the proposed model (Gerring,

2004).

The rationale of selecting a single case study in

this research is that it serves as a revelatory case

since there is lack of empirical studies that define

CSFs or a model for CNO effective IT governance.

The data were collected through conducting two key

informant interviews, distributing questionnaires,

observation of a steering committee meeting and

gathering related documents. Since this study targets

the strategic level of a CNO, the case study focuses

on two main groups as a unit of analysis; the

steering committee as it consists of senior managers

and chief executives of partner organizations and the

project management office as it deals with the IT-

related activities/decisions and the service-level

management group. Those members have the most

knowledge about the collaboration project including

its processes, decisions and challenges. To have an

in-depth knowledge of how this CNO operates and

is managed, two interviews were conducted, one

each with the service provider vice president and the

project management office director. The

questionnaires include both closed and open

questions. They were distributed to sixteen members

from both the steering committee and the project

management office and nine responses were

received. Quantitative and statistical analysis was

done on the questionnaires responses to evaluate the

importance and usefulness of the proposed CSFs and

KPIs. Responses were categorized to understand the

core tendencies emerging from the questionnaire.

4.1 Case Organization Background

The case CNO is the first MEDITECH “patient care

and technology” collaboration in the province of

Ontario, in Canada. It is a voluntary-based

partnership between six hospitals, which work

together and share information services to improve

the delivery of patient care and services to clients in

the region. These hospitals have implemented an

electronic patient record system project together.

MEDITECH is the information system that

integrates and connects the six hospitals in order to

provide health services. The objective of the case

CNO is to provide end-to-end care delivery.

4.2 Discussion

Based on the data collected from participants in the

CNO through both interviews and questionnaires, it

appears that all the critical success factors proposed

in this research are perceived to be important for the

collaboration to succeed. Some, however, were

deemed to be more important than others. Based on

the views of the vice presidents and CEOs of the

case CNO partner hospitals, some factors were rated

as more critical than others. The importance of the

CSFs may depend on the nature of the partnership

and its goals and objectives.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

198

Figure 2: CNO phases and assigned CSFs of IT

governance.

Some IT governance practices have been

observed to be vital at specific stages of the

implementation of the shared project. The case CNO

is still at the implementation phase of the shared

information system, and the collaborative considers

some of the factors to be important but only at a later

time, once the system is fully implemented and

operational. Based on the insights of the case CNO

steering committee members into IT governance, the

proposed CSFs could be classified according to three

main phases of execution for a shared project; these

phases are the formation of the CNO, the

implementation of the shared project, and the project

operation, as seen in Figure 2. Accordingly, some

factors such as providing ongoing training and

awareness for use of IT, implementing a

performance measurement system, and enforcing

policies and guidelines for use of IT would only be

deliberated once the shared system is fully

implemented.

The case CNO does not have any performance

measurement systems or metrics to assess the

performance of partners, although these types of

measures will be considered by the collaborative

once the shared project is totally implemented.

Based on the questionnaires distributed to the

members of the steering committee and the project

management office, the proposed KPIs were

evaluated and it is agreed upon that the KPIs are

useful as measurement tools for the various

dimensions of effective IT governance. They believe

that selecting KPIs for the collaborative highly

depends on the nature of the CNO and its goals and

objectives. Accordingly, some indicators may be

helpful but not essential for the CNO. The value for

the business perception of IT was considered

somewhat efficient for assessing business-IT

alignment and was ranked as the least useful KPI.

There needs to be both a direct and an indirect value

of IT, some aspects of which can be quantified and

others not.

4.2.1 Communication and Culture: Most

Critical Success Factors

The most noticed challenges and the most important

factors in a CNO are related to communication and

cultural differences. Those two factors are

continuous challenges, even when a new member

joins the CNO. Due to the high intensity of

interactions among CNO members, miscom-

munication always occurs, whether between the

collaborative’s various members and groups, or

internally at individual organization sites. In the case

CNO steering committee, there are usually two vice

presidents representing large institutions: one in

nursing and the other in operations. These two VPs

alternate to attend the monthly meetings of the

steering committee and communication issues arise

when there is no debrief between these two members

as of what was discussed during the meeting.

Besides, there are serious communication issues at

the partners’ individual organizations, where the

responsible individual fails to take the feedback and

information back to their organization, as they do

not communicate properly. Thus, inadequate internal

processes at each individual hospital sometimes get

in the way of effective communication and therefore

affect the overall performance of the collaborative.

For cultural differences, because the CNO

consists of independent organizations with different

needs and different expectations and capabilities,

members continuously have to be flexible and

responsive in order to effectively manage these

complex differences. It is not only important to unify

subculture beliefs and practices within a network,

but rather to be flexible in decision making and

responsive to the unique needs of the individual

organizations.

4.2.2 Trust

According to Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23), trust is

defined in the context of relationship marketing as

“when one party has confidence in the exchange

partner’s reliability and integrity”. In addition,

Moorman et al. (1993, p. 82) defined trust as “a

willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom

one has confidence”. Both definitions of trust in the

literature highly value confidence according to their

field of study. The definitions demonstrate that

confidence is dependent on the reliability and

AModelofEffectiveITGovernanceforCollaborativeNetworkedOrganizations

199

integrity of partners. Thus, a partner is trustworthy

when he possesses qualities such as being honest,

reliable, and consistent.

Furthermore, in the literature, trust depends on a

partner’s reputation and history. According to

Provan and Kenis (2007), trust is defined as the

willingness to accept vulnerability based on

reputation and past interaction experiences. In

addition to viewing trust in that context, Meyerson et

al. (1996) described trust in terms of long-term

relationships as being history-dependent. According

to both definitions, trust builds incrementally,

accumulates over time, and is affected by the history

of partners.

In the context of trust in collaboration, Vangen et

al. (2003) state that in order to sustain sufficient

levels of trust between partners, a continuous effort

is required due to the dynamic nature of

collaboration. Vangen et al.’s description of trust

comes close to the notion of dynamism. While the

literature points to trust as something that needs to

be "managed", in the CNO, it is more of an emergent

construct that varies continuously based on the

actions of the partners. In this context, it does not

need to be managed per se but rather emerges as a

consequence of what the partners do relative to what

they said they would do.

Although trust appears to be, at least in the

literature, a complex concept, it is much simpler in a

CNO since it is based directly on the actions of

partners. According to the interviews conducted for

this study, trust is based on the present interaction

experience and the actual behavior of the partners.

Within a CNO, especially in a health care context,

the foundation of trust is continually being re-forged

based on the immediate actions of the partners. A

partner who does the things he or she promised to do

is considered trustworthy. If a partner commits to

doing something and does it, trust increases.

However, if the commitment is not delivered, then

trust goes down.

Therefore, trust in a CNO is developed through

the constant evaluation of a partner’s behavior

versus his/her commitment. In the current

literature, trust in collaboration is conceptualized as

one party having confidence in the exchange

partner’s reliability and integrity. While, as the

literature suggests, a reputation for being trustworthy

based on past experience can help create initial trust,

the point emerging from this study is that trust is

continually updated as partners demonstrate through

their actions their willingness to do the things they

said they would do to help the collaborative.

4.2.3 The Health Care Aspect

There are likely contextual elements to this notion of

trust as an emergent feature of CNOs. The health

care context calls for high reliability, as errors can

have serious consequences. Health care facilities

therefore have to conduct relatively error free

operations and make consistently good decisions

resulting in high quality and reliability (Roberts,

Madsen, Van Stralen, and Desai, 2005). Health care

organizations are exposed to a higher level of risk

since they deal with people’s lives. Thus, they need

to ensure they provide optimal services to patients,

with the least amount of errors.

In addition, the high complexity and often times

diminishing resource base of a typical health care

institution means that one of the ways for the

hospital to maintain high quality and reliability of

services is to collaborate with other health care

facilities. Therefore, the motivation to collaborate

might be more pronounced in this environment than

in a private sector context.

Since the case CNO brings a specific value to its

partners, which is to deliver end-to-end patient care,

organizations are encouraged to participate in order

to improve their operations. Essentially, the case

CNO provides an electronic infrastructure

“MEDITECH” that allows organizations to develop

innovative and collaborative solutions that improve

the quality of the services provided, reduce

operational costs, and gain a competitive advantage.

Moreover, since hospitals operations and patient

care are time sensitive, collaboration facilitates the

provision of services in a timely manner. All the

mentioned benefits of collaboration are considered

strong motivators of participation and they help

increase the reliability of the services provided by

the health care facility. Consequently, senior

managers of that facility would have more interest in

being part of the shared project. This situation

suggests that a partner who does not deliver on a

stated commitment could create serious issues for

the collaborative and for partner institutions.

Accordingly, it follows that little margin for error

exists and therefore a partner’s behaviors relative to

their stated commitments are continually evaluated.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the findings of this research and of the

case study, we arrived at three main conclusions.

First, very few formalized CNOs seem to exist. The

healthcare environment case study used for this

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

200

research suggests that certain conditions likely

encourage formalization of the CNO. For example,

organizations operating in high risk, complex

environments where resources are limited tend to

focus more on formalizing their IT processes and

communication, since they require low error rates,

safety, and a high reliability of processes and

services.

Second, the sector’s characteristics might

influence the perception of the CSFs. For example,

the concept of trust between partners in CNOs is

simpler and more dynamic than what the current

literature suggests: it is continually formed and

adjusted according to the behaviors of the partners

versus their commitment. In addition, the distinctive

characteristics of the CNO in the healthcare context

influence the demonstration of values and the

behavior of senior managers. When partner

organizations tend to voluntarily participate in the

shared project, they would naturally be very

supportive, committed, and more trusting. Thus,

performance measurement systems and benchmarks

are not considered to be very important to the

success of the collaboration.

Third, the goals and objectives of a single CNO

can influence the IT-related success factors and their

assigned KPIs. For example, policies and guidelines

related to IT, IT structures, and standardizing IT

infrastructures don’t have to be consolidated in

situations where the CNO organizations need to

maintain their autonomy. There may not need to be a

consolidation. In fact, perhaps the infrastructure

should be owned by a third party. To illustrate, the

case study CNO adopts a central hybrid

model/structure to manage and control the IT tools.

One partner plays the role of the leading

organization and the service provider that directly

manages any of the collaborative IT infrastructures,

while the other partners make use of IT in a

collaborative way. This form of IT governance

structures, in which IT is centrally controlled, was

preferred among other structures to avoid accidents

that could possibly affect multiple hospitals.

REFERENCES

Ali, S. and Green, P. (2007). IT governance mechanisms

in public sector organisations: An Australian context.

Journal of Global Information Management, 15(3),

41–63.

Brown, A., and Grant, G. (2005). Framing the

frameworks: A review of IT governance research.

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems, 15, 696–712.

Camarinha-Matos, L., Afsarmanesh, H., Galeano, N., and

Molina, A. (2009). Collaborative networked

organizations – Concepts and practice in

manufacturing enterprises. Computers and Industrial

Engineering, 57(1), 46–60.

Camarinha-Matos, L. M., and Afsarmanesh, H. (2008). On

reference models for collaborative networked

organizations. International Journal of Production

Research, 46(9), 2453-2469.

Chong, J., and Tan, F. (2012). IT governance in

collaborative networks: A socio-technical perspective.

Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for

Information Systems, 4(2), 31–48.

Ferguson, C., Green, P., Vaswani, R., and Wu, G. (2013).

Determinants of effective information technology

governance. International Journal of Auditing, 17, 75–

99.

Guldentops, E., CISA, and CISM. (2004). Key success

factors for implementing IT governance. Information

Systems Control Journal, 2.

Huang, R., Zmud, R., and Price, R. (2010). Influencing the

effectiveness of IT governance practices through

steering committees and communication policies.

European Journal of Information Systems, 288–302.

Ko, D., and Fink, D. (2010). Information technology

governance: An evaluation of the theory-practice gap,

Corporate Governance, 10, 662–674.

McEvily, B., and Zaheer, A. (2004). Architects of trust:

The role of network facilitators in geographical

clusters. Trust and distrust in organizations, ed. R.

Kramer and K. Cook, 189–213. New York: Russell

Sage Foundation.

Melville, N., Kraemer, K., and Gurbaxani, V. (2004).

Information Technology and Organizational

Performance: An Integrative Model of IT. Business

Value, 28(2), 283–322.

Morgan, R. M., and Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-

trust theory of relationship marketing. The Journal of

Marketing, 20-38.

Prasad, A., Green, P., and Heales, J. (2012). On IT

governance structures and their effectiveness in

collaborative organizational structures. International

Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 13(3),

199–220.

Provan, K., and Kenis, P. (2007). Modes of network

governance: Structure, management, and

effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration

Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252.

Rabelo, R., and Gusmeroli, S. (2006). A service-oriented

platform for collaborative networked organizations.

IFAC.

Richards, J. (January, 2006). Trust and strong business

culture identified as key to IT governance. Retrieved

April 13, 2014, from http://www.computer

weekly.com/feature/Trust-and-strong-business-

culture-identified-as-key-to-IT-governance.

Roberts, K., Madsen, P., Van Stralen, D., and Desai, V.

(2005). A case of the birth and death of a high

reliability healthcare organisation. Quality and Safety

in Health Care, 14(3), 216–220.

AModelofEffectiveITGovernanceforCollaborativeNetworkedOrganizations

201

Rusu, L., and Nufuka, E. (2011). The effect of critical

success factors on IT governance performance.

Industrial Management and Data Systems, 111(9),

1418–1448.

Sambamurthy V, Zmud RW. (1999) Arrangements for

information technology governance: A theory of

multiple contingencies. MIS Quarterly, 23(2), 261–90.

Tapia, R., Daneva, M., Eck, P., and Wieringa, R. (2008).

Towards a Business-IT Alignment Maturity Model for

Collaborative Networked Organizations. University of

Twente, Department of Computer Science.

Weill, P. (2004). Don’t just lead, govern: How top-

performing firms govern IT. MIS Quarterly Executive,

3(1), 1–17.

Weill, P., and Woodham, R. (2002). Don’t just lead,

govern: Implementing effective IT governance.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sloan School

of Management. Cambridge, MA: Center for

Information Systems Research.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case Study Research: Design and

Methods (5

th

edition). SAGE Publications.

ICE-B2015-InternationalConferenceone-Business

202