The Impact of Household Structures on Pandemic Influenza Vaccination

Priority

Hung-Jui Chang

1,2

, Jen-Hsiang Chuang

3

, Yang-Chih Fu

4

, Tsan-Sheng Hsu

1

, Chi-Wen Hsueh

2

,

Shu-Chen Tsai

1

and Da-Wei Wang

1

1

Institute of Information Science, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

2

Depart of Computer Science and Information Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

3

Epidemic Intelligence Center, Centers for Disease Control, Taipei, Taiwan

4

Institute of Information Social, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

Keywords:

Household Structure Distribution, Agent-based Simulation, Vaccination Policy.

Abstract:

The household structure is an important aspect of population based simulation. How to generate a mock pop-

ulation with specific household structure characteristics is thus an important question. The network structure

is one of the dominant factors for contact-based disease transmission. And household structure is the most

important source of close contact among small groups. We identify the percentage of elderly-children house-

holds as an important character and study the process to generate mock population with specified percentage of

elderly-children households. The generated mock populations are fed into the agent-based simulation module

to study the impact of household structure on vaccination policy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Household structures are important for many appli-

cation domains. Household structures change over

time and vary geographically and culturally (OECD,

2011). Network structures affect the disease spread-

ing patterns. Household structure is an important

component of the transmission network of infectious

disease. Because of the strong interactions present,

households are one of the most important hetero-

geneities to consider, both in terms of predicting epi-

demic severity and as a target for intervention (House

and Keeling, 2009).

Family are different in different area. Among

the Asian countries, at least 80 percent of children

are raised by two-parent families, and at least 40

percent are also living with extended family mem-

bers (Trends, 2013), while in Europe at least 15

percent are living with extended family members.

For example, the percentage of households where

grandparents live with grandchildren is reported to be

ranged from 9.2 percentage to 20.5 percent in Asia

and from 0.1 percent to 3.9 percent in western and

northern Europe, Table 1.

Taiwan is approaching an aging society at an

Table 1: The household structure in Europe and

Asia(http://ec.europa.eu/).

country m<15 & M≥65(%)

Asia

Indonesia <09.2

Taiwan <15.0

Thailand <16.5

Vietnam <20.5

Europe

Belgium <00.1

Finland <00.9

Germany <01.1

Italy <03.1

Luxembourg <00.7

Netherlands <00.1

Poland <03.9

United Kingdom <00.9

M: the oldest person’s age in a family.

m: the youngest person’s age in a family.

alarming rate, due to the rapid decline of birthrate as

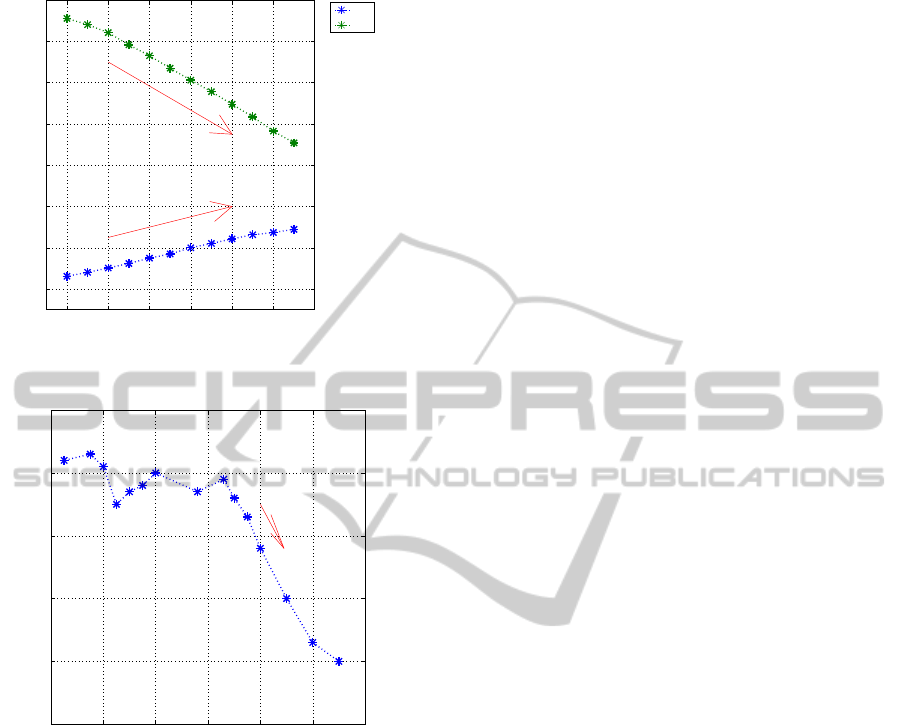

well as longer life expectancy. As shown in Figure

1, from 2000 to 2012, the youth population (less then

15 years old) dropped from 21 percent to 15 percent,

while senior population (age 65 and up) increased

from 8 percent to 11 percent. The average household

size is also declining for decades, from 5.9 in 1966

to 3.0 in the 2010, Fig 2. It is conceivable that the

482

Chang H., Chuang J., Fu Y., Hsu T., Hsueh C., Tsai S. and Wang D..

The Impact of Household Structures on Pandemic Influenza Vaccination Priority.

DOI: 10.5220/0005539204820487

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications (SIMULTECH-2015),

pages 482-487

ISBN: 978-989-758-120-5

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

Ratio(%)

The ratio of 65+ and 0-14 in Taiwan

65+

0-14

Figure 1: The ratio of over 65 years old and 0-14 in

Taiwan(2000–2011).

1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020

2

3

4

5

6

7

Household Size

The Household Size in Taiwan

Figure 2: The household size in Taiwan(1900–2010).

living or parenting arrangements in Asia may differ

from those in the West. It is not uncommon in Tai-

wan that grandparents live with grandchildren, or for

grandparents to help taking care of their young grand-

children on a daily basis. In such a circumstance,

both care givers (seniors) and care takers (toddlers or

young children) may have much more contact than

their counter parts in countries where seniors do not

live with young children. And the fact that these two

age groups are also most susceptible to influenza in-

fections makes this pattern evenmore interesting from

disease prevention perspective. ”Does this special

feature of age composition within the household con-

tribute to any divergent cross-cultural patterns of dis-

ease infections? When contact patterns in everyday

life are subject to such cultural norms, policy makers

should make the best use of diary-generated empirical

data and design intervention strategies accordingly”

(Fu et al., 2012).

We study the household structure of two cen-

sus data from Census 2000 and Census 2010 in Tai-

wan. In order to study the impact of household struc-

ture on epidemiology, we have to find a method to

generate mock population with specific household

structure characteristics. A simulation approach to

generate household structure is proposed by Geard

et al. (Geard et al., 2013). In this paper we pro-

posed to formulate it as a mathematical program-

ming. The specific household characteristics are the

primary constraints and other ”desired properties” are

secondary constraints. The generated mock popula-

tions are applied to explore the impact of household

structure on vaccination priority for influenza. We

use the agent-based disease spreading simulation soft-

ware to carry out our studies (Tsai et al., 2010). The

concepts of the simulation software is similer to Ger-

mann’s work.(Germann et al., 2006). And based on

the census data from 2000 and 2010 to generate our

initial sample population. Given a specified ratio of

elderly-children households, a transformation process

is developed to generate the sample population with

the given ratio from the initial population. Two vac-

cination policies are compared, namely, school chil-

dren only and elderly only. The rationales to vaccine

school children only are two folds. First, students

have close contact with each other, vaccinating stu-

dents can reduce the number of students infected by

other students. So that the chance of a school age

kid brings virus home is reduced. Second, it is more

cost effective to vaccinate students because they are

at a centralized location - the school. The rationale to

vaccinate elderly only is mainly to reduce the number

of severe cases and fatal cases.

We note that the selected vaccination policies are

only for demonstration the effect of household struc-

ture on disease spreading.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD

The household structure for the generation of a mock

population is a probability distribution over house-

hold patterns.

The specific of the possible patterns depends on

the applications. In this paper, the entire population

is classified into five age groups: preschoolers (0−4

years old), school-age children (5−18 years old),

young adults (19−29 years old), adults (30−64 years

old), and elders (65+ years old). And a household

pattern is a ten dimensional tuple, for 5 age groups

and genders, that is we keep track on the number

of males and females in each age group of a house-

hold. We set seven to be the upper bound of each

TheImpactofHouseholdStructuresonPandemicInfluenzaVaccinationPriority

483

entry. Therefore, there are 8

10

possible patterns and

each pattern can be encoded in 4 bytes. Let H denote

the set of patterns, a household structure distribu-

tion(HSD) is a probability space, (H, p) where func-

tion p maps an element in H to a probability. A char-

acteristic of household structure is a measurement of

the HSD. For example, the percentage of elders (over

65), or the percentage of households with preschool-

ers and elders. However, it would be difficult to know

the percentage of household in which children live

with both parents because we do not capture that rela-

tion in our setting. Usually, we have some other data

related to or constraint on household structure distri-

bution such as the age distribution of the population.

In general, we can treat any statistical measurements

of a population as soft constraints and the goal is to

generate a mock population that ”satisfies” them.

Since all the surveys and measurements are snap-

shots and subjected to noises, it is usually impossible

to satisfy all the constraints. For our study, the impor-

tant characteristic of a HSD is the elder-children ratio

(EC ratio), which is the percentage of householdswith

elderly and a young person under 15. Since the HSD

does not capture enough information to determine if

a school-age child is under or over 15 years old, we

have to utilize the age distribution data from the cen-

sus to decide stochastically the age of a school-age

child.

The mock population is constructed according to

national demographics and daily commuter (worker

flow) statistics from Taiwan Census 2010 Data

(http://www.stat.gov.tw/) in order to retain some pop-

ulation characteristics.

The generated mock population with desired HSD

is fed into the simulation software developed by Tsai

et al. (Tsai et al., 2010). Below is a brief description

of the simulation module.

The connection between any two individuals indi-

cates the possibility of regular (daily) and relatively

close contact that could result in the successful trans-

mission of the flu virus. An important parameter is the

disease depends on transmission probability denoted

P

trans

. It is the probability that an effective contact

results in an infection.

A contact group is a close association of individ-

uals, where every member is connected to all other

members in the group. We designate ten classes of

such contact groups in our model: community, neigh-

borhood, household cluster, household, work group,

high school, middle school, elementary school, day-

care center, and playgroup. It is important to note that

these contact groups do not represent all people at any

physical location such as a workplace or school, but

rather the groups of people who share the same sur-

rounding activities and sustain regular close contact

for potential viral infection.

Each individual is a member of one of the five age

groups throughout the simulation can belong to sev-

eral contact groups simultaneously at any time. The

probability of any two individuals staying in contact

that could result in the successful transmission of the

flu virus is called the contact probability, and an em-

piric value is assigned depending on the group where

contact occurs and the ages of both individuals.

Age not only affects the probability of an individ-

ual being infected, it also determines the individual’s

daytime contact groups: preschoolers stay either in

daycare centers or in playgroups; school-age children

stay either in schools or in households as dropouts;

young adults and adults stay either in work groups or

in households if unemployed.

Each simulation runs in cycles of two 12-hour pe-

riods, daytime and nighttime, with each cycle repre-

senting a day in the simulation. The simulation can

cover any specified duration of days; we usually oper-

ate in 180 days for typical influenza season, but there

are times when 365 days duration is imperative for a

slow progressing epidemic. Contact occurs between

individuals in each contact group every day, there are

no exceptions for weekends or holidays until we can

properly ascertain their effects.

During nighttime, contact occurs only in commu-

nities, neighborhoods, household clusters, and house-

holds; whereas in the daytime, contact occurs in all

contact groups. Children do not go outside of their

residential community for daytime activities because

the probabilities for such occasional contacts are too

low to be captured by any contact group. The only

inter-community transmission occurs when working

adults commute between household and work group

as specified by worker flow data as well as school

children commute between household and school as

specified by school flow (Tsai et al., 2010).

To derive a series of household structure with

specified EC ratio, we designed a simple household

structure evolution process to transform the set of pa-

rameters so that the percentageof EC household in the

mock population generated by the modified parame-

ters is sufficiently close to the designated number. We

formulate the process as a linear programming prob-

lem, the objective function is designed to avoid intro-

ducing dramatic ”changes” to other important aspects

of the household structures. The detail is described in

Figure 3.

A simulation setting is a set of parameters, which

include p

trans

and household structure. To study the

effect of vaccine policies, we fix a simulation setting

and simulate each vaccination policy. For each policy,

SIMULTECH2015-5thInternationalConferenceonSimulationandModelingMethodologies,Technologiesand

Applications

484

Input Household Structure

Is EC?

Yes No

EC family Non-EC family

Calculate Modification

Bounded Condition Constraint condition

Linear Programmming

Combine Household Structure

Turned size

Original size

Output Household Structure

Figure 3: Flow Chart of Using Linear Programming.

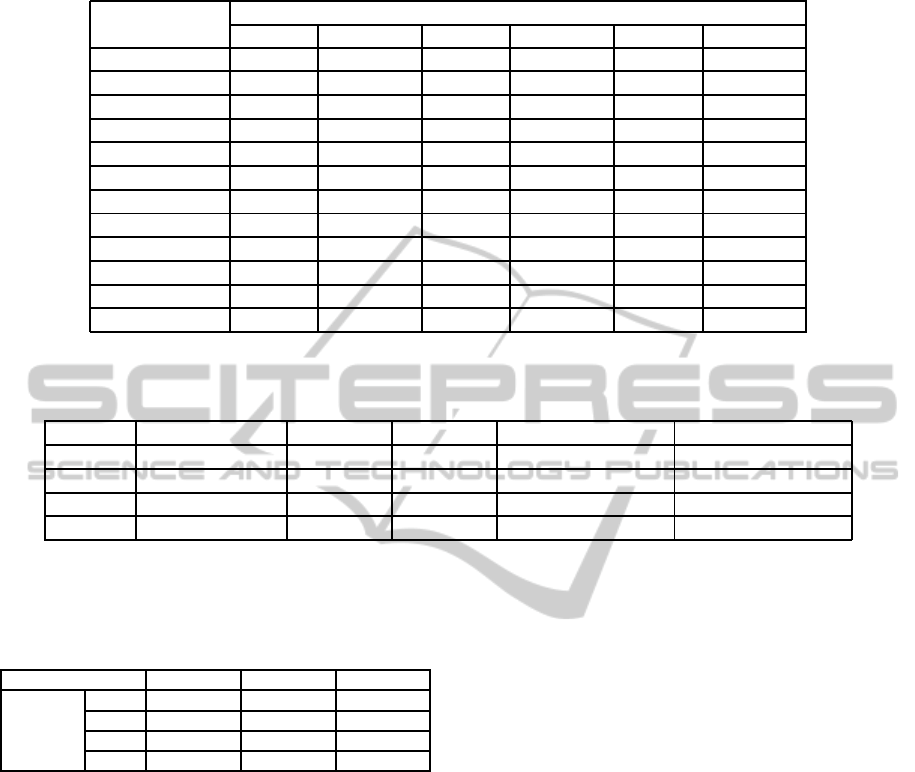

Table 2: The household size in each EC ratio(mock population).

EC ratio #population #0-4 #5-18 #19-29 #30-64 #65+ household size

30% 23,088,322 972,361 4,265,569 3,079,993 11,588,807 3,181,592 3.09

20% 23,087,718 938,074 4,217,799 3,124,340 11,686,059 3,121,446 3.05

10% 23,086,465 897,650 4,156,653 3,182,322 11,791,448 3,058,392 3.01

0.0% 23,079,732 970,817 4,262,075 3,078,738 11,590,107 3,177,995 2.78

’#’: the number of

we first carry out the baseline simulation which is the

simulation without any intervention. Then the simu-

lation with intervention policies are carried out with

the same setting. We start the vaccination at the 70

th

days and the number of available vaccine is 1.8 mil-

lion doses, the vaccine efficacy is set at 36%− 90%.

For each simulation run, we record the number of

infected cases for each group. We then take the aver-

age of simulation runs with the same setting and in-

tervention policy to be the outcome of that specific

policy.

The difference between the baseline and a inter-

vention policy is the effect of the intervention, and in

our case it is the difference of the number of infected

cases of each age group.

Note that we compare different policies with the

same setting and only focus on the number of infected

cases for each age group. If the numbers of reduced

infected cases for one policy, A, is always better than

the other policy, B, we can safely conclude that policy

A is superior than policy B. However, if a vaccination

policy is to set the priority of receiving vaccination

among age groups, it will be difficult to find a supe-

rior policy because a policy targeted at a specific age

group always results in the fewest infected cases for

that group.

We introduce a cost function, C which maps a five

dimensional point (the numbers of infected cases for

each age group) to a real number. Given a policy A,

the cost saved by A is C(base) −C(A), that is the cost

difference between baseline and policy A. We say that

policy A is better than policy B with respect to cost

functionC, if and only if the cost saved by A is greater

than B. For example, if we define C(n

1

, n

2

, n

3

, n

4

, n

5

)

to be the summation of the five numbers, we are com-

paring the number of infected cased reduced. The

costs of infected cases among different age groups

can be different (Meltzer et al., 1999). Here we adopt

a cost function which highlight the different between

elderly and others. Let C be a cost function with pa-

rameter α be:

C

α

(n

1

, n

2

, n

3

, n

4

, n

5

) = n

1

+ n

2

+ n

3

+ n

4

+ α∗ n

5

Function above captures the idea that the cost of

an elderly case is α times of the other age groups and

TheImpactofHouseholdStructuresonPandemicInfluenzaVaccinationPriority

485

the costs of all the other age groups are the same. We

define an equilibrium point for policy A and B to be

α∗ such that C

α∗

(A) = C

α∗

(B). Since C

α

is a linear

function, there is a unique equilibrium point between

two policies.

3 RESULTS

From the HSD perspective, the census data from

2000(C2000) and 2010(C2010) can be described as

following: there are 11283 household patterns in

C2000, 7072 in C2010 and a total of 11543 patterns

ever appeared in C2000 or C2010. There are 6813

patterns appeared in both C2000 and C2010. The

summation of the probability of the common pat-

terns is greater than 0.99 for both C2000 and C2010.

The Pearson correlation between these two HSDs is

around 0.95. There are 4470 patterns only appeared

in C2000 while 259 only in C2010. The apparent dis-

crepancy is due to the fact that C2010 only survey 16

percent of the household while C2000 surveyed every

household.

Based on processes described above, we success-

fully generated populations with specified character-

istics. In Table 2, the generated mock populations

have specified EC ratio, and the population is highly

correlated with original population, the Pearson cor-

relation ranging from 0.998 to 0.999.

The R

0

for the baseline case of each mock popu-

lation is calculated and summarized in Table 3. We

note that with the same transmission probability, the

lower the EC ratio the smaller the R

0

. And this can

be explained by the fact that average household size

decreases as EC ratio decreases. That is the differ-

ence of the network structure is the main reason for

the variation in the table.

We compare two vaccination policies, student

only and elder only. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

From the summary, we note that the student only

policy outperforms elder only for all age group except

seniors. That is the student only policy reduced the

number of infected cases more than elder only policy

in all four age groups excluding seniors. The can be

Table 3: R

0

.

transmission probability

EC ratio 0.08 0.09 0.10 0.11

30% 1.055 1.194 1.308 1.442

20% 1.053 1.182 1.302 1.432

10% 1.041 1.169 1.294 1.428

0.0% 0.910 1.122 1.247 1.352

50 100 150 200 250

0

20000

40000

60000

80000

100000

120000

140000

Day

Daily new infected cases

Daily new infected cases

30%

20%

10%

0.0%

Figure 4: Daily new infected cases in different EC-family

ratio.(P

trans

is 0.09).

explained by the fact that compared with seniors the

students have more contacts. Therefore, vaccinating

students not only protect the vaccinated students also

limits the spreading more than vaccinating seniors.

Two cost functions are applied to compare the cost

benefit of different policies, one is the cost matrix

from Melzer (Meltzer et al., 1999) and the other is

the cost function with parameter α, which is cost ra-

tio between the elderly and other age groups. The

results applying Melzer cost matrix is summarized in

Table 5. We again observe that student only policy

outperforms elder only. The results of applying C

α

are summarized the value of the equilibrium points in

Table 6. We note that the value of the equilibrium

point increases when EC ratio lowered, this is a curi-

ous phenomena needs further investigation.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

DISCUSSION

We designed a simple method to generate household

structure distribution with specified characteristics.

The method can ensure that the resulting distributions

are ”similar” to the original distribution. A more thor-

ough study maybe needed to give the method a more

solid theoretical foundation. The household structure

distribution can have impact on the vaccination prior-

ity. However, to apply the method to real situation at

least following issues have to be explored.

First, instead of using point estimation, that is the

average outcome of simulation runs, interval estima-

tions are necessary for policy makers to have more

information about the difference among different op-

tions. Instead of taking the average of simulation

runs, we can observe important outcome variables as

sampled by simulation runs. Based on our past ex-

periences, most of the observed quantities fit normal

SIMULTECH2015-5thInternationalConferenceonSimulationandModelingMethodologies,Technologiesand

Applications

486

Table 4: Basic data(P

trans

is 0.09).

infected cases

0-4 5-18 19-29 30-64 65+ total

30%(baseline) 239,745 1,706,801 956,525 3,441,096 954,530 7,298,697

30%(p1) 220,505 1,630,385 882,697 3,165,843 673,903 6,573,333

30%(p2) 194,734 1,093,766 811,178 2,877,378 793,026 5,770,082

20%(baseline) 225,593 1,669,545 955,546 3,410,050 915,534 7,176,268

20%(p1) 206,630 1,587,315 875,068 3,113,949 620,845 6,403,807

20%(p2) 177,356 1,005,881 789,590 2,773,512 739,373 5,485,712

10%(baseline) 208,842 1,622,788 955,966 3,371,757 873,679 7,033,032

10%(p1) 191,289 1,542,433 873,912 3,072,764 584,062 6,264,460

10%(p2) 161,939 958,344 781,978 2,712,316 698,209 5,312,786

00%(baseline) 199,815 1,567,902 847,755 3,034,015 717,711 6,367,198

00%(p1) 187,902 1,506,673 783,991 2,801,450 462,770 5,742,786

00%(p2) 141,077 832,923 640,380 2,246,715 525,263 4,386,358

p1 is elder only.

p2 is student only.

Table 5: Cost in Meltzer’s work(P

trans

is 0.09).

EC ratio baseline(x10

9

$) p1(x10

9

$) p2(x10

9

$) baseline-p1(x10

9

$) baseline-p2(x10

9

$)

30% 54.03 48.18 44.16 5.85 9.87

20% 53.24 47.01 42.23 6.23 11.01

10% 52.34 46.12 41.06 6.22 11.28

0.0% 46.78 41.70 33.63 5.08 13.15

p1 is elder only.

p2 is student only.

Table 6: The equilibrium point under different transmission

probability and EC ratio.

P

trans

0.09 P

trans

0.10 P

trans

0.11

EC ratio

30% 7.74 3.99 2.85

20% 8.74 4.16 2.93

10% 9.34 4.40 3.03

0.0% 22.71 7.15 4.39

distribution well. Interval estimations of normal dis-

tribution can then be applied.

Second, it is observed that policy options depends

on the transmissibility of the virus which is not ob-

servable before the pandemic starts. Therefore, a

carefully designed early estimation process is very

important. The process will utilize the early data

about the epidemic to predict important parameters

which are important for decision makers. We believe

that early data, say for the first 2 months, can be ap-

plied to get good estimations. But more experiments

are necessary to ensure it.

Third, more policy options should be evaluated. In

this study, we only consider two options. To make real

life recommendations, more options should be evalu-

ated. Forth, it is beneficial to design good visualiza-

tion methods to facilitate decision process.

REFERENCES

Fu, Y.-c., Wang, D.-W., and Chuang, J.-H. (2012). Repre-

sentative contact diaries for modeling the spread of in-

fectious diseases in taiwan. PLoS One, 7(10):e45113.

Geard, N., McCaw, J. M., Dorin, A., Korb, K. B., and

McVernon, J. (2013). Synthetic population dynam-

ics: A model of household demography. Journal of

Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 16(1):8.

Germann, T. C., Kadau, K., Longini, I. M., and Macken,

C. A. (2006). Mitigation strategies for pandemic in-

fluenza in the united states. Proceedings of the Na-

tional Academy of Sciences, 103(15):5935–5940.

House, T. and Keeling, M. J. (2009). Household struc-

ture and infectious disease transmission. Epidemiol-

ogy and infection, 137(05):654–661.

Meltzer, M. I., Cox, N. J., Fukuda, K., et al. (1999). The

economic impact of pandemic influenza in the united

states: priorities for intervention. Emerging infectious

diseases, 5:659–671.

OECD (2011). Doing better for families. Technical report,

Paris.

Trends, C. (2013). World family map 2013: Mapping family

change and child well-being outcomes. World Family

Map.

Tsai, M.-T., Chern, T.-C., Chuang, J.-H., Hsueh, C.-W.,

Kuo, H.-S., Liau, C.-J., Riley, S., Shen, B.-J., Shen,

C.-H., Wang, D.-W., et al. (2010). Efficient simula-

tion of the spatial transmission dynamics of influenza.

PloS one, 5(11):e13292.

TheImpactofHouseholdStructuresonPandemicInfluenzaVaccinationPriority

487