Can Playing Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games

(MMORPGs) Help Older Adults?

David Kaufman and Fan Zhang

Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC, V5A 1S6, Canada

Keywords: Digital Games, Videogames, Older Adults, Seniors, Aging, Social Connectedness, Loneliness.

Abstract: Gerontology researchers have demonstrated that social interaction has profound impacts on the

psychological wellbeing of older adults. This paper addresses the question of whether and how playing

Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs) help older adults. We analyzed the

relationships of older adults’ social interactions in Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games

(MMORPGs) to three social-psychological factors (i.e., loneliness, depression and social support). A total

of 176 web surveys were usable from the 222 respondents aged 55 years or more who played World of

Warcraft and were recruited online to complete the survey. It was found that enjoyment of relationships and

quality of guild play had strong impacts on older adults’ social and emotional wellbeing. Specifically,

higher enjoyment of relationships was related to higher social support as well as lower levels of loneliness.

Higher quality of guild play was related to higher levels of social support and lower levels of loneliness and

depression.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Social Interaction and Successful

Aging

The move away from the extended family toward a

more nuclear family (as children have left home),

the loss of a partner, decline of health status,

difficulties with mild cognitive impairment,

retirement from workforce are implicated in the loss

of social contacts, which in turn are expected to

increase the risk of loneliness and depression

(Heylen, 2010; Mirowsky and Ross, 1992).

Loneliness, a lack of social support, and having a

deficit of reliable or frequent contacts with friends or

relatives are closely inter-related (Grey, 2009).

Research has shown many negative health effects of

loneliness and social-isolation, including poor

mental and physical health, memory deficits, sleeps

disturbances and so on (Masi et al., 2011).

Gerontology researchers have demonstrated that

cognitive and social factors are key elements to

enhance older adults’ quality of life. Social

interaction has profound impacts on physical health

and psychological well-being. People who have

close friends and confidants, friendly neighbours,

and supportive co-workers are less likely to

experience sadness, loneliness, low self-esteem, and

problems with eating and sleeping, whereas people

who are socially disconnected are between two and

five times more likely to die from all causes

(Putnam, 2000). As one gets older, people who

maintain close friendship and find other ways to

interact socially have reduced risk of mental health

issues and live longer than those who become

isolated (Singh and Misra, 2009). Eisenberger,

Taylor, Gable, Hilmert and Lieberman’s (2007)

study yielded supportive evidence that individuals

with regular social interaction during 10 days

showed diminished neuroendocrine stress responses

and distress of social separation. Therefore, some of

the social and psychological problems faced by older

adults could be improved by increasing their social

interactions.

1.2 Social Interactions in MMORPGs

Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games

(MMORPGs) have become a leisure activity of older

adults. Yee’s (2006b) study found that the mean age

of the respondents was 26 years, with a range from

11 to 68. Williams, Yee and Caplan (2008) reported

that 12.4% of EverQuest II (a MMORPG) players

527

Kaufman D. and Zhang F..

Can Playing Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) Help Older Adults?.

DOI: 10.5220/0005551405270535

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (AGEWELL-2015), pages 527-535

ISBN: 978-989-758-107-6

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

were in their forties, and 4.8% were fifty and older.

Yee (2008) found that MMORPG players, on

average, spent 22 hours each week in an MMORPG;

players over the age of forty played just as much as

players under the age of twenty.

MMORPGs allow a group of players to play

together no matter where they are physically located.

To enter a game world, players first create a

character from a set of classes and races as digital

representations of themselves. When creating their

character, users play the role of a character living in

the game’s fantasy world. Each character has a

specific set of skills and abilities that define that

character’s role. Nearly all MMORPGs featured a

character progression system in which players earn

“experience points” for their actions and use those

points to reach progressively higher “levels”.

Social interaction is a primary driving force for

players to continue to play MMORPGs, and

contributes a considerable part to the enjoyment of

playing (Yee, 2006a). One difference between

MMORPG and other social networking sites (such

as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) is that

MMORPGs have functional constructs (e.g., unique

attributes of each character and challenging quests

that can’t be addressed by a single player) that

encourage players to group with others and complete

a same quest for mutual benefits. These functional

constructs facilitate some social groups, known as

guilds. A guild is an organized group of players that

regularly play together, and formed to make

collective actions easier and more rewarding, as well

as to form a social atmosphere.

Players join or create guilds for their pragmatic

or social needs. The most common reason to join a

particular guild is to use their membership as a

resource to meet their game goals, such as having

access to the game’s most challenging content and

most rewarding “loot”, high-end content (e.g.,

equipment, weapons, and exciting monsters). Some

players want to play with others who share similar

personality, real-life demographics, or even sense of

humor. Some players see their guildmates as nice,

friendly and useful. In some cases, game friends are

seen as important as real-life friends.

Players form contacts and develop relationships

of trust and accountability based on their characters’

attributions, actions, and the network of affiliations

(Dickey, 2007).When a new group is formed, a chat

channel is automatically created that only group

members can use. This allows players to request

help, strategize on group quests and socialize.

Additionally, they can also interact with other

through person-to-person instant messaging, Voice

over IP (an Internet-based auditory chatting system)

and site forums.

Schiano, Nardi, Debeauvais, Ducheneaut and

Yee (2011) found that the majority of World of

Warcraft (WoW, a popular MMORPG) players play

the game with someone. Cole and Griffiths (2007)

reported that 26.3% of participants played

MMORPGs with family and real-life friends.

Whippey (2011) reported that 82% of participants

who were involved in guild life often had

conversations with their guild mates; 66% often

spend time playing with their guild. It was found in

Williams et al.’s (2006) study that 60% of guild

members used Voice IP systems, and roughly 60%

of interviewees belonged to a social guild in which

the primary goal is social interaction. Yee (2006c)

reported that 39.4% of male players and 53.3% of

female players felt that their MMORPG friends were

comparable or better than their real-life friends. In

Whippey’s (2011) study, 54% of participants felt

that their game friends were comparable to their

real-life friends. Therefore, playing MMORPGs

provides many opportunities to sustain off-line

relationships and develop meaningful and supportive

new relationships.

1.3 Previous Studies Testing the

Social-Psychological Effects of

MMORPGs

Many studies have focused on testing the social-

psychological impacts of playing MMORPGs.

Visser, Antheunis and Schouten (2013) examined

the effects of playing WoW on adolescents’

loneliness. It was found that there was no difference

in the level of loneliness between WoW players and

non-WoW players, and there was also no significant

effect on loneliness of time spent playing WoW.

Kirby, Jones and Copello (2014) explored the

association between average hours playing WoW

per week and psychological wellbeing through a

cross sectional online questionnaire. A negative

correlation between playing time and psychological

wellbeing was revealed. These two studies

correlated self-reported measures of playing time

with measures of psychological wellbeing, but found

conflicting results.

Dupuis and Ramsey (2011) tested a mediated

model in which they examined whether higher social

involvement in MMOPRGs would be associated

with lower levels of depression via engendering a

perception of social support. Game involvement was

measured by a 13-item scale developed by the

researchers. Sample items are “If I had a personal

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

528

problem that was really bothering me, I would rather

tell my online friends than friends I have in real

life”, and “I have more good friends online than I do

in real life.” It was found that involvement in

MMORPGs was not related to perceived social

support, but a lack of perceived social support is

associated with higher levels of depression. Trepte,

Reinecke and Juechems’s (2012) study found that

online game players’ physical and social proximity

as well as their mutual familiarity influenced

bridging and bonding social capital, and the two

types of social capital were positively associated

with offline social support. Domahidi, Festl and

Quandt’s (2014) study found that there was a

significant impact of social online gaming frequency

(measured by general gaming frequency and the

average duration of a typical social online gaming

session) on the probability of meeting exclusively

online friends, and players with a pronounced

motive to gain social capital and to play in a team

had the highest probability to transform their social

relations from online to offline context. These

studies went beyond the simple measure of playing

time, but social interactions in MMORPGs were

conceptualized differently.

2 RESEARCH QUESTION

It is well established that social interaction is seen as

an important component of successful aging (Ristau,

2011). MMORPGs are a wholly new form of

community, social interaction and social

phenomenon. Playing MMORPGs links people from

all over the world as they engaged in a shared virtual

world and collective play experience. It can maintain

real-life relationships and facilitate new

relationships, and therefore provides more

opportunities to obtain social resources.

Then, the research question is: Are there

relationships between the social interactions in

MMORPGs and various social-emotional benefits

for older adults (i.e., loneliness, depression and

social support)?

3 DEFINITION OF VARIABLES

Before drawing any conclusions about the impacts

of MMORPGs, the underlying variables involved in

older adults’ social interactions in MMORPGs

should be determined (Williams et al., 2006). As

discussed above, previous studies used amount of

game play as the gross measure. Frequent

participation in game play increases the chance of

social interactions but this doesn’t depict the whole

picture of social interactions in MMORPGs. Shen

and Williams (2011) indicated that whether MMO

use were associated with negative or positive

outcomes was very much dependent on the

purposes, contexts, and individual characteristics of

users.

Thus, this study conceptualizes social

interactions in MMORPGs as follows:

(1) Communication Methods.

Communication is the most important aspect of

players’ interactions in MMORPGs (Shen and

Williams, 2011). Nardi and Harris’s (2006) study

found that chatting is a key aspect of socializing in

WoW, which takes place not only when grouping

and fighting, but also when players are soloing or

traveling in WoW.

(2) Network Level. This refers to the position

of players in their social network. It is another key

variable when understanding the outcomes of

MMORPG playing (Williams, 2010). Shen, Monge

and Williams (2012) indicated that the measure of

network level is essentially the same as centrality.

Individuals who are in central position within a

network are usually more accessible than others

(Freeman, 1978/79).

(3) Enjoyment of Relationships. It affects

how much social support players can exchange by

playing together. Game play is constituted not only

by joint in-game activities but also overwhelmingly

by constant conversation about the game and topics

well beyond it, ranging from debates about the

mechanics of the game and intimate personal

problems. Some players trust their game friends and

see them as important as real-life friends, while

others see their game friends as not particularly

important to them (Williams, et al., 2006).

(4) Quality of Guild Play. In MMORPGs,

guild is a place where deep relationship occurs

(Steinkuehler and Williams, 2006). Players in

formally structured guilds tend to have more social

experiences than others (Williams et al., 2006). This

positively affects the quality of their time in the

game. So, quality of guild play determines whether

its impact on social interactions is positive or

negative.

4 METHODS

4.1 Participants

Participants were older adults who were aged 55 and

CanPlayingMassiveMultiplayerOnlineRolePlayingGames(MMORPGs)HelpOlderAdults?

529

over, English speakers and WoW players. A total of

222 people submitted their surveys, of which 176

provided their demographic information as well as

fully completing the survey. These were the

responses used in the analysis.

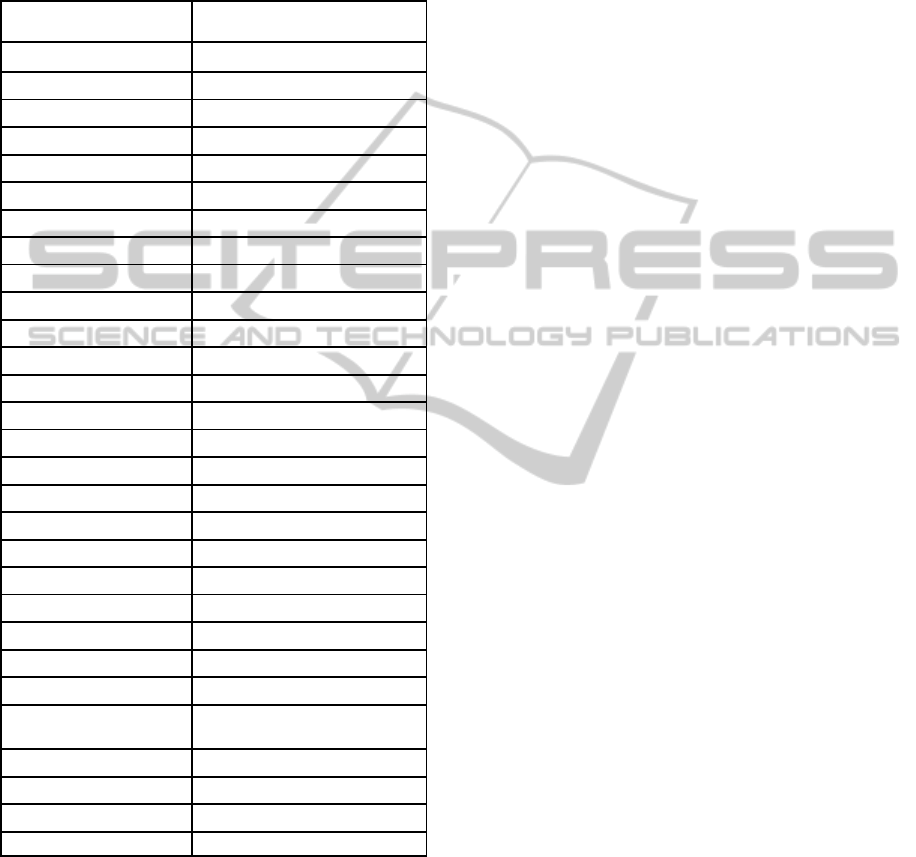

Table 1: Participant demographics.

Variable Frequency (%)

Gender

Female 58(32.8%)

Male 119(67.2%)

Age

55-59 111(62.7%)

60-64 37(20.7%)

65+ 29(16.4%)

Relationship

Married 109(61.2%)

Separate/Divorced 37(20.8)

Widowed 9(5.1%)

Never married 23(12.5%)

Living situation

Spouse/Common law 53(42.1%)

Family 33(26.2%)

Others 8(6.3%)

Alone 32(25.4%)

Work situation

Full-time employed 95(53.1%)

Part-time employed 17(9.5%)

Retired 61(34.1%)

Never employed 6(3.4%)

Educational level

Less than high school 9(5.0%)

High school (or

equiv.)

33(18.4%)

Four-year degree 70(39.1%)

Master’s degree 36(20.1%)

Doctoral degree 14(7.8%)

Other 17(9.5%)

The background information about respondents is as

follows. Approximately 33% were female, and 67%

were male. Yee’s (2006b) study found that

MMORPG players are roughly 85% male. Thus,

compared with young adults, there were more

female older MMORPG players.

A significant majority of older gamers (62.7%)

were aged between 55 and 59, while only 20.9%

were between 60 and 64, and 1.2% fall into the 70-

79 age group. The big proportion of older gamers

who were in the age group of 55-59 justifies the use

of “55” as the lower age cut point. More notably,

6.2% of participants are among the oldest players

(those 80 years of age or older).

In terms of relationship status, 61% of

participants were married and 20.8% were separated

or divorced. One fourth of participants (25.4%) lived

alone, while others lived with spouse or common

law partner (42.1%), family (26.2%), or someone

else (6.3%).

More than half of the participants (53.1%) were

full-time employed and 9.5% were part-time

employed.

For the highest level of education, 39.1% of

participants had completed a four-year degree,

20.1% completed a master’s degree and 7.8% had a

doctoral degree.

Regarding gameplay patters, 40% of participants

play WoW seven days per week on average, 12.2%

play 6 days per week and an identical 12.2% play 5

days per week. Fully 41% of participants spend 2 or

3 hours per day on average playing WoW, and

28.4% play 4 to 5 hours per day, while some 22%

play more than 6 hours per day. Taken together,

65% of participants play WoW at least 5 days per

week, and on average 92% spend 3 or 4 hours per

day playing WoW, which equals the working hours

of a part-time job.

Surprisingly, a substantial majority of

participants already were at the high end of the

game. The highest level of approximate 84.2% of

participants’ main character (a main character is the

one participants play most often if they play several

characters.) is 80 and higher. (In 2014, the maximum

level was 90).

4.2 Description of the Game

WoW was selected as the intervention tool in this

study. On the one hand, with different types of

games, it is unrealistic to assume that all games have

uniform effects (Shen and Williams, 2011;

Williams, 2010). Therefore, examining all

MMORPGs rather than just one game will hinder

the generalizability of the results. On the other hand,

WoW is the most popular MMORPGs (the current

North American MMORPG leader), currently

having more than 10 million subscribers.

One genre of game that provides many

opportunities for social interactions is the Massive

Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game

(MMORPG). Massive refers to the fact that millions

of players play these online games; multiplayer

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

530

identifies the fact that a very large number of players

play simultaneously in the same online world,

interacting with each other; Online indicates that the

players need to be connected to the Internet while

they play; Role-Playing, in general, refers to player

who play the role of a unique character and interact

with other players by using an “avatar”, which is a

humanoid graphical representation of the player in

the game world.

To enter a game world, players first create a

character from a set of classes and races as digital

representations of themselves. When creating their

character, users play the role of a character living in

the game’s fantasy world. Each character has a

specific set of skills and abilities that define that

character’s role. For example, in World of Warcraft

mages are powerful spell casters who use magic to

inflict damage on their enemies from afar but are

very vulnerable to attacks. These traits define the

role of the mage: hang back, do a ton of damage, and

hope to kill the monsters before they reach the

player. Players also have the option of choosing their

sex and adding various adornments to enhance their

characters appearance as they progress in the game,

such as hair color, clothing, armor, etc. Due to these

characteristics, MMORPGs are anonymous

environments in which players have many

opportunities to experiment with different online

identities. In contrast to other genres of games,

MMORPGs do not have storylines. A MMORPG

community is as dynamic and complex as the real

world. A typical group requires players to fulfil a

number of roles, which are summarized as kill,

irritate, and preserve (Barnett and Coulson, 2010). A

good group needs an appropriate balance of all three

roles and successful team cooperation and

coordination in order to stand a realistic chance of

success. Players may invest hundreds of hours

advancing their character and interacting in the

virtual environment, and thus players often feel an

emotional proximity to their character. In

MMORPGs, players begin the game as low-level

member. During gameplay, the development of the

player’s character is the primary goal. Nearly all

MMORPGs feature a character progression system

in which players earn “experience points” for their

actions and use those points to reach progressively

higher “levels”. Over the course of a character’s life,

the character will brave thousands of quests while

exploring the game environment, learn new and

powerful abilities, and find hundreds of powerful

weapons and more. In other words, the character

progresses and gets stronger as the player gain

experience, new skills, and more powerful items and

equipment. MMORPGs do not have an ending or

finishing time. Even after achieving the highest

level, players may still remain in the game world to

complete more challenges or participate in the social

communities of which they have been part.

4.3 Survey Design

The final survey consisted of three sections. The first

section focussed on playing patterns (i.e., amount of

game play and level of main character) and social

motivation for playing MMORPGs. Social

motivation was measured using the Online Gaming

Motivations Scale (Yee, Ducheneaut, and Nelson,

2012). Its reliability is .77. The second section asked

questions about older adults’ social interactions

within WoW. It included four measurements:

(1) Communication methods was measured by

asking how frequently older adults communicate

with others via public chat, group chat, private chat,

in game voice chat, social media and face-to-face

meeting. Participants were asked to indicate on a 5-

point scale (1=Never, 5=All the time) the frequency

of using these communication tools.

(2) Network level was measured by asking

how frequently older adults play with family, real-

life friends, game friends and other players.

Respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point

scale (1=Never, 5=All the time) the frequency of

playing with these persons.

(3) Enjoyment of relationships was measured

by the strength of relationship with family, real-life

friends and game friends. Respondents were asked

to indicate on a 5-point scale (1=Strongly disagree,

5=Strongly agree) to what extent they agree with

these statements: (a) Playing with family members

makes me feel closer to them; (b) Playing with real-

life friends makes me feel closer to them; (c) I trust

my game friends; (d) My game friends are as

important to me as my real-life friends. They were

also asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (1=Never,

5=All the time) how often they engage in these

actions: (a) Talk about WoW with my family;(b)

Talk about WoW with my real-life friends; (c) Share

my personal problems with game friends. These

statements were identified as deep relationships by

Steinkuehler and Williams (2006) and Williams et

al.’s (2006) study.

(4) Quality of guild play was measured by

time of guild play and satisfaction with guild play.

Satisfaction with guild play was measured by asking

respondents to indicate how satisfied they are with

the organization of the guild, guild leadership and

guild members with “1” referring to “Very

CanPlayingMassiveMultiplayerOnlineRolePlayingGames(MMORPGs)HelpOlderAdults?

531

dissatisfied” and “5” referring to “Very satisfied”.

The third section consists of the three socio-

psychological measures:

(1) Loneliness. This was assessed with the

short-form of the UCLA Loneliness scale (ULS-8;

Hays and DiMatteo, 1987). UCLA Loneliness scale

is an instrument indexing the frequency of an

individual’s feelings of loneliness and lack of

companionship. Participants rated each item on a

scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly

agree) with higher scores indicating lower levels of

loneliness. The reliability is .88.

(2) Depression. This was measured by the 10-

item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression

scale (CES-D; Mirowsky and Ross, 1992). CES-D is

designed to assess the current level of depression,

and is one the most commonly used in a normal, as

opposed to a pathological, population. It is rated on a

5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5

(Strongly agree) with higher scores indicating lower

levels of depression. Its reliability is .86.

(3) Social support. This was measured by the

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

(MSPSS; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, and Farley, 1988).

The MSPSS measures how one perceives their social

support system, including an individual’s sources of

social support (e.g., family, friends and significant

other). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-scale

ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly

agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of

perceived social support. Its reliability is .93.

Invitation messages including the URL to the

Web survey were posted on eight WoW player

forums.

4.4 Data Analysis

The purpose of this research was to examine the

associations of some social-psychological benefits

with older adults’ social interactions in MMORPGs.

As discussed above, amount of game play is an

important factor (but not the only one) that affects

the level of psychological wellbeing. Also, game

play will likely be more social for some than for

others (Bartle, 2004). So, controlling for amount of

game play and social motivation, a series of two-

stage hierarchical regression analyses were

performed, using each of the social-psychological

measures as outcome variable, and the factors in

each component of social interactions in MMORPGs

as independent variables. Then, to compare the

effect size of each component of social interactions

on each outcome measure (e.g., which one of the

four components of social interactions in

MMORPGs generated the biggest effect size on

loneliness?), Cohen’s f

2

of each individual

hierarchical regression analyses was computed. By

convention, effect sizes of .02, .15 and .35 are

termed small, medium, and large, respectively

(Cohen, 1988). Data analysis was carried out using

IBM Statistics SPSS 22.0. In terms of the many

multiple regression used, all regression analyses

were carried out with an alpha level of .01.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Playing Time

No significant differences in playing time were

found in terms of relationship status (F (3, 174) =

.723, p =.539), living situation (F (3, 122) = 1.014, p

= .389) and work situation (F (3, 175) = 1.138, p =

.335).

5.2 Associations among Variables

Because of the small percentage of participants in

age groups 65-69, 70-74, 75-79 and 80+, these were

combined as 65+. A one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) revealed that the three age groups (i.e.,

55-59, 59-64, and 65+) differed significantly from

each other in the time they spent playing WoW (F

(2, 174) = 5.600, p = .004). A Bonferroni post hoc

test indicated that the age group 65+ (M = 3.31, SD

= 1.198) played significantly more than the age

group 55-59 (M = 2.59, SD = 1.030, p = .004) and

the age group 59-64(M = 2.62, SD = .953, p = .026).

In view of the participants` education, the

ANOVA analysis indicated that playing time also

differed significantly (F (5, 173) = 2.583, p = .028).

A Bonferroni post hoc test revealed that the less than

high school group (M =3.78, SD = 1.563) spent

significantly more time playing games than did the

high school group (M = 2.61, SD = .933, p = .050),

4-year degree group (M = 2.60, SD = .954, p = .026),

and master`s degree group (M = 2.61, SD = 1.050, p

= .048).

5.3 Predictors of Outcome Variables

For depression and social support, the amount of

game-play and social motivation were significant

predictors. The amount of game-play was negatively

associated with depression (p = .005), i.e., more

play was associated with lower depression.

Reduction in loneliness was mostly predicted by

playing with family. Regarding the results of

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

532

enjoyment of relationships, this was mostly

predicted by playing with real-life friends.

When the four variables for quality of guild play

were entered to the model, all of these variables

were statistically significant predictors of loneliness,

depression and social support. Loneliness was

mostly predicted by satisfaction with guild mates.

Depression was predicted from quality of guild play.

Similar to loneliness, it was mostly predicted by

satisfaction with guild mates.. For social support,

this was mostly due to satisfaction with guild

leadership.

Table 1 presents Cohen’s effect size (f

2

) for all

outcome measures. The biggest effect sizes for

loneliness, depression, and social support were all

associated with quality of guild play. The biggest

effect sizes for loneliness (f

2

= .156) and depression

(f

2

= .156) were identical, and their magnitude is

medium. The magnitude of the biggest effect size for

social support (f

2

= .202) is medium to large. What’s

more, communication methods and network level

generated smaller effects sizes for loneliness,

depression and social support compared with the

effects sizes generated by enjoyment of relationships

and quality of guild play. The magnitudes of the

effect sizes generated by communication methods

and network level were small.

Table 2: Cohen’s effect size for outcome measures.

Mea-

sure*

Communi-

cation

Methods

Net-

work

Level

Guild

Leader-

ship

Quality

of

Guild

Play

L .015 .067 .114 .156

D .049 .037 .060 .156

Ss .004 .057 .191 .202

*L: Loneliness; D: Depression; Ss: Social support

6 DISCUSSION

Instead of using the gross measure of playing time as

to quantify MMORPG use, this study categorized

social interactions into four components:

communication methods, network level, enjoyment

of relationships and quality of guild play, and

analyzed how these were associated with loneliness,

depression and social support. It is found that

network level was negatively associated with

loneliness; higher levels of enjoyment of

relationships were related to higher levels of social

support and lower levels of loneliness; higher levels

of quality of guild play were related to higher levels

of social support and lower levels of loneliness and

depression.

In addition, the biggest effect sizes for

loneliness, depression and social support were all

generated by quality of guild play. Loneliness and

depression were mostly predicted by satisfaction

with guild mates and social support was predicted by

satisfaction with leadership. This phenomenon could

be the result of the membership of guilds. Due to the

in-game mechanism (for example, guild members

need to coordinate with each other in order to

achieve the task), guild members tend to have

similar values and play styles. As a result of this

collective identity, trust and friendship is more likely

to be developed among guild members through

repeated collaboration in groups and raids (Shen,

2014). Shen’s (2014) study found that guild

membership is positively related to players’ level of

sociability. Guild players were more likely than non-

guild players to participate in social activities such

as chat, trade and collective quests. Loneliness,

depression and social support are related to the

benefits/support/resources existing in interpersonal

contact of social networks. Participation in guild

activities provides older adults many opportunities

for informal sociability, and thus could be an

important source of interpersonal relationships and

social support.

Communication methods and network level

generated smaller effects sizes for loneliness,

depression and social support compared with the

effects sizes generated by enjoyment of relationships

and quality of guild play. This finding is predictable

and reasonable. Communication methods and

network level provides older adults many

opportunities to interact with other players and

exposes them to different viewpoints, but they don’t

indicate the intention or content of these activities.

Communicating and collaborating with other players

(no matter which tool is used or with whom) does

not automatically create a deep social bond among

them.

It was also found that amount of time of game

play was not associated with older adults’ feelings of

loneliness, depression and social support when other

variables related to the social interactions in

MMORPGs were taken into account. This is

compatible with the finding of Shen’s (2014) study

that time spent had a very small overall impact on

players’ psychosocial well-being. Instead, the social

and psychological impacts of playing MMORPGs

on older adults are very much dependent on the

CanPlayingMassiveMultiplayerOnlineRolePlayingGames(MMORPGs)HelpOlderAdults?

533

contexts of game play, enjoyment of the

relationships and the quality of guild play.

7 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The first limitation of this study is associated with

survey research. All the data collected for this study

were self-reports. As such, issues of social

desirability and accuracy of responses need to be

taken into account. The second limitation is related

to the web survey. As discussed above, the majority

of participants are heavy gamers, and most of them

have reached high levels of the game. This might

result in our sample being biased towards expert

players. Finally, the sample comprised volunteers

who were willing to complete the survey.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This study explored the social and psychological

impacts of playing MMORPGs (i.e., WoW) on older

adults aged 55 and over, primarily analyzing the

relationships between older adults’ social

interactions in MMORPGs and three social and

psychological factors. The regression analyses

revealed that enjoyment of relationships and quality

of guild play has deep impacts on older adults’

social and psychological wellbeing. This study

contributes to the knowledge of older adults’ social

experiences in MMORPGs and how it influences

their social and emotional lives. The findings can

form a solid foundation for conducting future

randomized controlled trials to measure and evaluate

the impacts of MMORPG playing on older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

for their financial support of this research study.

REFERENCES

Barnett J. and Coulson M. (2010) Virtually real: A

psychological perspective on massively multiplayer

online games. Review of General Psychology 14(2):

167–179.

Bartle R. (2004). Designing virtual worlds. Indianapolis,

IN: New Riders Publishing.

Cohen J. (1988) Statistical power analysis for the

behavioral sciences (2

nd

ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Cole H. and Griffiths M.D. (2007) Social interactions in

Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games.

Cyber Psychology & Behavior 10(4): 575-583.

Dickey M.D. (2007) Game design and learning: A

conjectural analysis of how massively multiple online

role-playing games (MMORPGs) foster intrinsic

motivation. Educational Technology Research and

Development 55(3): 253–273.

Domahidi E., Festl R., and Quandt T. (2014) To dwell

among gamers: Investigating the relationship between

social online game use and gaming-related friendships.

Computers in Human Behavior 35: 107-115.

Dupuis E.C. and Ramsey M.A. (2011) The relation of

social support to depression in Massively Multiplayer

Online Role-Playing Games. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology 41(10): 2479-2491.

Eisenberger N.I., Taylor S.E., Gable S.L., Hilmert C.J. and

Lieberman M.D. (2007) Neural pathways link social

support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses.

NeuroImage 35: 1601-1612.

Freeman L.C. (1978/79) Centrality in social networks:

Conceptual clarification. Social Networks 1: 215-239.

Grey A. (2009) The social capital of older people. Ageing

& Society 29: 5-31.

Hays R.D. and DiMatteo M.R. (1987). A short-form

measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality

Assessment 51(1): 69-81.

Heylen L. (2010) The older, the lonelier? Risk factors for

social loneliness in old age. Ageing & Society, 30(7):

1177–1196.

Kirby A., Jones C. and Copello A. (2014) The impact of

Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games

(MMORPGs) on psychological wellbeing and the role

of play motivations and problematic use. International

Journal of Mental Health Addiction 12: 36-51.

Masi C.M., Chen H.Y., Hawkley L.C. and Cacioppo J.T.

(2011) A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce

loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology 15(3):

219-266.

Mirowsky J. and Ross C.E. (1992) Age and depression.

Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33(3): 187-

205.

Nardi B. and Harris J. (2006) Strangers and friends:

Collaborative play in World of Warcraft. In

Proceedings of the 20

th

anniversary conference on

computer supported cooperative work (pp.149-158).

New York: ACM.

Putnam R.D. (2000) Bowling alone: The collapse and

revival of American community. New York: Simon &

Schuster.

Ristau S. (2011) People do need people: Social interaction

boosts brain health in older age. Journal of the

American Society on Aging 35(2): 70-76.

Schiano D.J., Nardi B., Debeauvais T., Ducheneaut N. and

Yee N. (2011) A new look at World of Warcraft’s

social landscape. Proceedings of the International

Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (pp.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

534

174-179). New York: ACM.

Shen C. (2014) Network patterns and social architecture in

Massively Multiplayer Online Games: Mapping the

social world of EverQuest II. New Media & Society

16(4): 672-691.

Shen C., Monge P. and Williams D. (2012). Virtual

brokerage and closure: Network structure and social

capital in a Massively Multiplayer Online Game.

Communication Research 41(4): 459-480.

Shen C. and Williams D. (2011) Unpacking time online:

Connecting Internet and Massively Multiplayer Online

Game use with psychosocial well-being.

Communication Research 38(1): 123-149.

Singh A. and Misra N. (2009) Loneliness, depression and

sociability in old age. Industrial Psychiatry 18(1): 51-

55.

Steinkuehler C.A. and Williams D. (2006) Where

everybody knows your (screen) name: Online games

as “third places.” Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication 11: 885-909.

Trepte S., Reinecke L., and Juechems K. (2012) The social

side of gaming: How playing online computer games

creates online and offline social support. Computers in

Human Behavior 28: 832-839.

Visser M., Antheunis M.L. and Schouten A.P. (2013)

Online communication and social well-being: How

playing World of Warcraft affects players’ social

competence and loneliness. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology 43: 1508-1517.

Whippey C. (2011) Community in World of Warcraft :

The fulfilment of social needs. Totem: The University

of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology 18(1):

49–59.

Williams D. (2010) The mapping principle and a research

framework for virtual worlds. Communication Theory

20: 451-470.

Williams D., Ducheneaut N., Xiong L., Zhang Y.Y., Yee

N. and Nickell E. (2006). From tree house to barracks:

The social life of guilds in World of Warcraft. Games

and Culture 1(4): 338-360.

Williams D., Yee N. and Caplan S.E. (2008). Who plays,

how much, and why? Debunking the stereotypical

gamer profile. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication 13(4): 993-1018.

Yee N. (2006a) Motivations for play in online games.

Cyber Psychology & Behavior 9(6): 772-775.

Yee N. (2006b) The demographics, motivations and

derived experiences of users of Massive Multiuser

Online Graphical Environments. PRESENCE:

Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 15: 309–329.

Yee N. (2006c) The psychology of MMORPGs:

Emotional investment, motivation, relationship

formation, and problematic usage. In R. Schroeder &

A. Axelsson (Eds.), Avatars at work and play:

Collaboration and interaction in shared virtual

environments (pp.187-207). London: Springer.

Yee N. (2008) Maps of digital desires: Exploring the

topography of gender and play in online games. In

Kafai Y, Heeter C, Denner J, and Sun J (Eds.) Beyond

Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New perspectives on

gender and gaming (pp. 83-96). Cambridge, MA: The

MIT Press.

Yee N., Ducheneaut N. and Nelson L. (2012) Online

Gaming Motivations Scale: Development and

validation. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual

conference on human factors in computing systems

(pp.2803-2806). New York: ACM.

Zimet G.D., Dahlem N.W., Zimet S.G. and Farley G.K.

(1988) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived

Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment

52(1): 30-41.

CanPlayingMassiveMultiplayerOnlineRolePlayingGames(MMORPGs)HelpOlderAdults?

535