Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?

Ritesh Chugh

School of Engineering and Technology, Central Queensland University, Melbourne, Australia

Keywords: Knowledge, Tacit Knowledge, Tacit Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Management, Encourage, University,

Academics.

Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to explore whether Australian universities encourage tacit knowledge transfer. In

doing so, the paper also explores the role of managers (academics’ supervisor) in promoting or hampering

tacit knowledge transfer and the value given to new ideas and innovation. This study collected data by

conducting interviews of academics in four universities and a qualitative narrative analysis was carried out.

The findings suggest that universities generally encourage and facilitate the transfer of tacit knowledge;

however there are some areas that require improvement. Avenues for improving tacit knowledge transfer call

for open communication, peer-trust and unrestricted sharing of knowledge by managers. The study was

conducted in four universities, hence limits the generalisability of the findings. This paper will contribute to

further research in the discipline of tacit knowledge, provide understanding and guide universities in their

tacit knowledge transfer efforts and in particular, encourage the transfer of tacit knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

Universities are knowledge institutions with

knowledge embedded in people and processes.

Universities are, also, an integral part of society and

play a key role in knowledge transfer. In universities,

knowledge is often tacit in the minds of academics

thus making it difficult to spread through the

university and its internal stakeholders, not limited to

students and other academics, because of time and

resource constraints. Tacit knowledge can be defined

as skills, ideas and experiences that people have in

their minds and are, therefore, difficult to access

because it is often not codified and may not

necessarily be easily expressed e.g. putting together

pieces of a complex jigsaw puzzle, interpreting a

complex statistical equation (Chugh, 2013). The role

of academics is to convey and transfer their tacit

knowledge into more explicit forms so that it is

available for further reuse by the stakeholders.

A report prepared by PhillipsKPA (2006) for the

Department of Education, Science and Training in

2006 showed universities are doing a lot for

knowledge transfer through commercialisation of

research, but less importance is placed on knowledge

transfer efforts made by universities in passing their

tacit knowledge to internal stakeholders who could be

students and academic peers. If knowledge remains

only tacit in the heads of a few individuals in an

organisation, then the organisation is putting itself at

risk and it is not always possible to move those few

individuals around. However once tacit knowledge is

converted into explicit, an organisation has a lower

risk of losing its intellectual capital when employees

leave the organisation (Davenport and Prusak, 1998).

Hence, knowledge management can be seen as a

viable approach to resolve organisational issues such

as competitive pressure (Cepeda, 2006; Prusak, 2006)

and the need for innovation (Parlby and Taylor,

2000). Effective knowledge management (KM) also

leads to reduced time to market, improved innovation,

and improved personal productivity (Miller, 1996).

The message that emerged from Loermans (2002) is

that ‘KM should focus more on the tacit component

of KM rather than on its contemporary emphasis on

explicit knowledge’ (p.293). The focus on tacit

knowledge is an indicator of its importance in modern

organisations who have constantly concentrated their

efforts on explicit knowledge alone. Social and

human factors are seen as key indicators of the

preparedness of individuals to share tacit knowledge

(Goh and Sandhu, 2013).

It is evident that tacit knowledge sharing is

important for universities. In a variety of contexts,

researchers have recognised the role of organisations

in encouraging the transfer of tacit knowledge (Smith,

128

Chugh, R..

Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 128-135

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2001), the role senior managers and leadership can

play in promoting tacit knowledge transfer (Lin and

Lee, 2004), and significance provided to innovation

(Foos et al., 2006). However, such research around

academics’ views in universities is still in its infancy.

Accordingly, this paper seeks to contribute to the

existing scant literature and fill the gap by enhancing

our understanding of the extent to which academics’

workplaces (universities) encourage the transfer of

tacit knowledge, specifically in an Australian context,

and identify some of the associated challenges.

Since most organisational knowledge is tacit in

nature, the sharing and communication of tacit

knowledge can be difficult.

From both a research and

applied perspective, negligible studies currently exist

that explore academics’ perception about whether

universities (their workplaces) encourage the sharing

of tacit knowledge. This paper will aim to

qualitatively address the research question that aims

to explore the extent to which academics’ workplaces

(universities) encourage the transfer of tacit

knowledge. In order to address the main research

question, three specific questions will be focussed

upon - assessing the role of universities/workplaces in

encouraging tacit knowledge transfer, role of the

manager (academic’s supervisor) in promoting or

hampering tacit knowledge transfer and finally, value

given to new ideas and innovation. For this purpose,

four post 1992 Australian universities were selected.

The remainder of this paper is organised as

follows. The next section presents a review of the

literature. The paper then provides an insight into the

research method adopted for the study and the

characteristics of the participants. Findings and

discussion then follow in section four. Finally, the

key premises of the research have been summarised

in the conclusion section and limitations are explicitly

stated with an outlook for possible further research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Tacit knowledge is considered as personal knowledge

that is difficult to express, formalise or share and

exists in an intangible format (Sveiby, 1997). Tacit

knowledge has been defined as ‘what people carry

around with them, what they observe and learn from

experience, and what is internalized and, therefore,

not readily available for transfer to another’

(Muralidhar, 2000, p. 222). Hislop (2009) indicates

tacit knowledge may not only be difficult to

articulate, it may even be subconscious. This

characteristic of tacit knowledge makes it difficult to

disembody from people and further codify it. Tacit

knowledge is reflected in human actions and their

interactions with the social environment (Nonaka,

1994; De Long and Fahey, 2000). Busch (2008) has

defined tacit knowledge as knowledge that cannot be

codified, is implicit in nature and not necessarily

written anywhere and not able to be readily

expressed. This implies that tacit knowledge would

include peoples’ skills, experiences, insight and

judgement. Tacit knowledge could also be termed as

‘sticky’ knowledge as it stays in the minds of people.

It is often known as preconscious knowledge based

on an understanding of the fitness of things,

instinctive actions and so forth. The epistemic value

of tacit knowledge is also a contentious issue and it is

difficult to study. Research suggests that 75 percent

or more of an organisation’s knowledge can be

categorised as tacit knowledge (Frappaolo and

Wilson, 2002; O’Dell, 2002). Often universities

operate in a turbulent and dynamic environment and

hence, it is crucial for universities to cater for tacit

knowledge transfer.

Converting tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge

becomes really important as Hislop (2009) states that

knowledge is primarily cognitive but is ultimately

codifiable. It is necessary to root out the knowledge

held in peoples’ heads to a tangible form. DeLong

(2004) proposes that ‘humans have been creating and

losing knowledge for thousands of years’ (pg. 20).

Housel and Bell (2001) assert that ‘knowledge resides

primarily within human heads; when ‘head count’ is

reduced, inevitably the sum of knowledge within the

organization is reduced, sometimes critically so’ (pg.

5). This problem of loss of head count could imply

different situations such as downsizing or when aging

employees leave the organisation with a lot of tacit

knowledge in their heads.

A study by Foos et al., (2006) collected data from

various individuals, representing three companies

charged with integrating external technology,

revealed that the subject of tacit knowledge transfer,

content, and process is poorly understood. The critical

factors which influence construction employees’

knowledge sharing behaviour were trust, creativity,

motivation, ability, and learning (Nesan, 2012).

Identifying and overcoming diverse knowledge

transfer barriers is vital in order to assist senior and

middle management in creating a systematically

driven collaborative environment where knowledge

sharing takes place easily (Riege, 2007). Finally,

knowledge management efforts should not be

restricted to one discipline only (Karlsen and

Gottschalk, 2004) thus it is important to assess the

role of universities in encouraging tacit knowledge

transfer.

Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?

129

Universities can be classified as knowledge

intensive organisations because they are coherent

with the definition of knowledge intensive firms

provided by Alvesson (2000, pg. 1101) as ‘companies

where most work can be said to be of an intellectual

nature and where well qualified employees form the

major part of the workforce.’ Other features of a

knowledge intensive firm are their workforce is

typically highly qualified and the knowledge and

skills of their workforce is a source of competitive

advantage (Swart and Kinnie, 2003). Considering

their characteristics, universities can undoubtedly be

considered as knowledge intensive firms and their

workers as knowledge workers. Hislop (2009) has

defined knowledge worker as a person who is

involved in primarily intellectual, creative and non-

routine work, and involves the creation and use of

abstract/theoretical knowledge. Academics, as

knowledge workers, possess and utilise different

types of knowledge to complete their work.

Knowledge transfer activities have not been

institutionalised and attention is required to their

management in universities (Geuna and Muscio,

2008).Various researchers (Baumard, 1999; Blair,

2002; Laupase, 2003) have identified obstacles to

tacit knowledge transfer but with little focus on

university academics or the role workplaces play in

encouraging the transfer of tacit knowledge. It is also

vital to understand how academics react to internal

and external factors when deciding whether to

participate in knowledge sharing activities or not

(Cheng et al., 2009). In similar vogue, Jain et al.,

(2007) have called out for the need to explore

academics’ views to encourage knowledge sharing

amongst them.

Workplaces play an important role in providing

the right environment for tacit knowledge transfer

(Smith, 2001; Chugh, 2013). Employees associate

knowledge with power and this can often make

knowledge sharing difficult (Liebowitz and Chen,

2003) and organisational leadership is also a barrier

to knowledge sharing (Seba et al., 2012). Poor

management practices such as hoarding tacit

knowledge, allocating insufficient time for

knowledge transfer and limiting relationships were

identified as barriers to achieving effective

knowledge transfer

(Clayton and Fisher, 2005). The

transfer of tacit knowledge in an organisation can

largely be driven by motivation and encouragement

by senior management (Chugh et al., 2014). Utilising

tacit knowledge also effectively indicates an

organisation’s innovativeness (Subramaniam and

Venkatraman, 2001) and can lead to competitive

advantage. Hence, the role of managers is crucial in

providing the right conditions for tacit knowledge

transfer to take place effectively.

Bartol and Srivastava (2002) have suggested that

knowledge sharing is vital to knowledge creation,

organisational learning, and performance

achievement. The intricate nature of tacit knowledge

is particularly perplexing for researchers and

practitioners, and this adds to the complexity in

readily being able to transfer tacit knowledge. Studies

(Empson, 2001; Bechina and Ndlela, 2007) have

found human, social and cultural factors were

important in determining the impact (success or

failure) of knowledge management initiatives.

Examining the impact of social dynamics in

sharing tacit knowledge processes between

employees is necessary to understand and

recommend improved facilitation measures. Since

most organisational knowledge is tacit in nature, the

sharing and communication of tacit knowledge can be

difficult. Hence it was considered necessary to assess

whether universities encourage the sharing of tacit

knowledge.

3 METHOD

Four post 1992 Australian universities (names

withheld for confidentiality reasons) have been

selected for this study, based on their long history in

the education sector as they evolved from colleges of

advanced education and institutes of technologies.

These four universities are undergoing a lot of

change, both in terms of organisational structure and

introduction of new programs, and are rapidly

strengthening their position towards the provision of

learning and teaching services to national and

international students. It is their uniqueness in the

education sector that makes them ideal for this study.

The study focussed on academics in universities

because academics can be classified as knowledge

workers who deal with tacit knowledge on a daily

basis. Academics produce knowledge, disseminate it

to a variety of stakeholders and utilise knowledge to

carry out their day-to-day tasks. Academics are very

important in the process of knowledge sharing and

reuse. Moreover, the solitary research instrument that

can reveal and build on tacit knowledge is the human

(Lincoln and Guba, 1985), hence academics were

considered to be suitable for data collection.

As qualitative methods, such as interviews, aim

at understanding the rich, complex and idiosyncratic

nature of human phenomena (Cavana et al., 2003), a

qualitative method namely in the form of interviews

was adopted. Qualitative research usually emphasises

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

130

the socially constructed nature of reality and

researchers are involved in achieving a rich

understanding of people’s experience and not

necessarily in obtaining information which can be

generalised to larger groups (Flick, 2006). Hence,

interviews were considered relevant to record,

analyse and uncover the meaning of academics’

experiences in tacit knowledge sharing. The views

provided by the respondents paint a picture of the

reality as reported ‘from the ground’.

In this study, interviews were deemed to be

important as they would provide an in-depth

opportunity to ask a series of open-ended questions,

which would reveal whether universities encouraged

tacit knowledge transfer, in an unconstrained

environment providing the opportunity to clarify and

explain information. Various questions were asked as

part of the interview but for the purposes of this paper

only three questions that are within the scope have

been analysed. The three specific questions focussed

upon - assessing the role of universities/workplaces in

encouraging tacit knowledge transfer, role of the

manager (academic’s supervisor) in promoting or

hampering tacit knowledge transfer and finally, value

given to new ideas and innovation.

Sample sizes in qualitative research should not be

too large otherwise it becomes difficult to extract

thick, rich data (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007).

Since the aim of this study is not to estimate the

prevalence of a phenomenon or to make

generalisations but to provide an understanding, to

develop explanations and to generate ideas, only a

small number of respondents were required. Thus for

the interviews, this study primarily employed a

stratified purposeful sample to identify academics (a

lecturer or senior lecturer and an associate professor

or professor from each university). A total of eight

interviews were conducted, which involved two

academics from each university.

After data collection, the data was open-coded

and analysed. The coding involved transcription of

the digital recordings and then multiple reviews were

carried out to identify and interpret repeating themes

and ideas. The hermeneutic paradigm was adopted for

analysis as it helps to explain relationships based on

a personal interpretative approach (Gummesson,

2000). The analysis of qualitative data in the next

section is based on a structured interpretative

approach drawing illustrative examples from each

interview transcript as required and a narrative has

been woven. Short direct quotes from the participants

have been included to aid in the understanding of

specific points of interpretation and a smaller number

of more extensive passages of quotations to provide a

flavour of the original texts have also added.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

It appears universities have gone in a much

mechanised direction in recent times with little

emphasis on rooting out tacit knowledge. In support

of this statement, one of the interviewee revealed that

‘universities are more bent upon bean-counting these

days, which is totally contrary to the philosophy of

transfer of tacit knowledge.’ This respondent’s

feeling also touches on the way universities should

value altruism, and how the current outlook is

incorporated into employment, promotion, rewards

and so forth. Most respondents believe their

university encourages and facilitates the transfer of

tacit knowledge however there are many deterrents

that came to the forefront. A lack of openness in

communication was seen as a deterrent with one

interviewee pointing out that ‘everyone is playing

safe and playing safe leads to disaster.’

Interviewees from one university felt that there

are certain cultural traits which in fact work against

tacit knowledge transfer. An interviewee noted that

‘the culture of the university – both at the faculty level

and at the university level totally undervalued, and it

did not trust, experience gained elsewhere.’ The

whole idea of tacit knowledge transfer is utilising the

skills and experience of people which they have

gained over their lifetime and it is these skills and

experience that can be used to provide value for

universities.

Managers play an important role in facilitating

the transfer of tacit knowledge. Apart from being

facilitators, they are themselves in an important

position of transferring tacit knowledge to others

reporting to them. However, most interviewees saw

their managers as being a deterrent in the transfer of

tacit knowledge. They perceived their managers as

information gatekeepers who were mostly very

reluctant to impart their tacit knowledge to others.

This result is similar to a study by Clayton and Fisher

(2005), which found that locking up tacit knowledge

was a barrier to achieving effective knowledge

transfer. One of the interviewee remarked their

manager lacked skills that would have promoted tacit

knowledge transfer. To this effect, the interviewee

said ‘Managers like these create a very tense work

environment. Which then doesn’t allow us to believe

in tacit knowledge transfer because if you’re going to

be reprimanded for every small thing that you are

trying to do, why would you do it?’ Undoubtedly

different types of leaders make different decisions

Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?

131

that can either hamper or enhance the sharing of

knowledge. Transformational leadership style is

considered a key driver of knowledge management

initiatives in an organisation. Transformational

leadership places greater emphasis on motivating

people and develops long term strategic visions and

further inspires people to work towards achieving that

vision (Vera and Crossan, 2004; Hislop, 2009).

Nonaka et al., (2006) have argued that leaders need to

enable the creation of knowledge. Transformational

leaders can be seen as enablers of knowledge

management initiatives in an organisation. Senior

management can help to create a valuable knowledge

sharing culture by being proactive and driving a

cultural change (Pan and Scarbrough, 1999).

Micromanagement is not seen as conducive to tacit

knowledge sharing efforts. The focus of micro-

management is towards day-to-day activities, short

term goals and operationally focussed rather than

being strategically focussed as in transformational

leadership.

The display of the information gatekeeper

characteristics by a manager led one interviewee to

comment that ‘I just couldn't get anything out from

him (immediate manager) and that frustrated me a lot

and lured me into a few mistakes I made, which I

could have avoided if information was passed on to

me, even just a little bit of it.’ This implies that

frustration and unnecessary mistakes can be reduced

if staff is provided access to information and

managers freely share their knowledge with staff

reporting to them. One of the interviewees

commented that displaying the traits of an

information gatekeeper by a manager as ‘the

antithesis to creativity. When people feel humiliated

there isn't a worse emotion to kill and curb motivation

than humiliation.’

The issue of power was also evident in the

responses provided by the interviewees. Managers

see themselves as the power-holders and are hence

prone to say that ‘don’t come to me, I don’t want to

tell you, you do it on your own’ (Interviewee). This

notion of information gatekeeper could be seen ‘as a

red flag in communication. This could also imply that

tacit skills are not being passed’ (Interviewee).

Knowledge sharing can sometimes be seen as

threatening and managers may be reluctant to share

as it impacts their status, esteem and power in the

university. Baumard and Starbuck (2005) have

argued that senior management are often responsible

for creating an unconducive environment for

employees’ unwillingness to share knowledge. Some

of the conditions in an unconducive environment

could be a culture where employees are reprimanded

for sharing, experimentation and risk taking is not

encouraged and inquiry of existing business practices

is seen as a threat.

In the case of an interviewee who saw their

manager as being a person who was not an

information gatekeeper, it was evident that trust was

an important part in the display of this trait. This

interviewee noted that ‘my manager would pass any

information to others, especially me, provided that I

keep it confidence, which I’ll always do. So I do prefer

this practice because it means I’m a trustworthy

person. More importantly, it certainly helps me to

make decisions and better or do my job more

efficiently and effectively. It especially helps me to

increase the accuracy of the work when information

is clear, is right in front of you.’ One of the

interviewee very aptly put that being an information

gatekeeper ‘depends from person to person’ and

managers need to ‘understand the importance of the

dissemination of information.’

The interviewees displayed a very equally divided

response to the value that their managers’ displayed

towards new ideas and innovation. One on the

interviewee remarked that ‘it is rhetoric in reality and

theory in practice.’ However it is evident that

academics generally prefer an open door policy that

promotes communication. One of the interviewees

noted that ‘We don’t see the managers. We don’t -

there’s no interaction. They take advice from a select

few people, which means that you don’t get the

chance.’ This comment could also imply that

managers need to involve more staff in decision

making rather than a select few and create a more

democratic workplace.

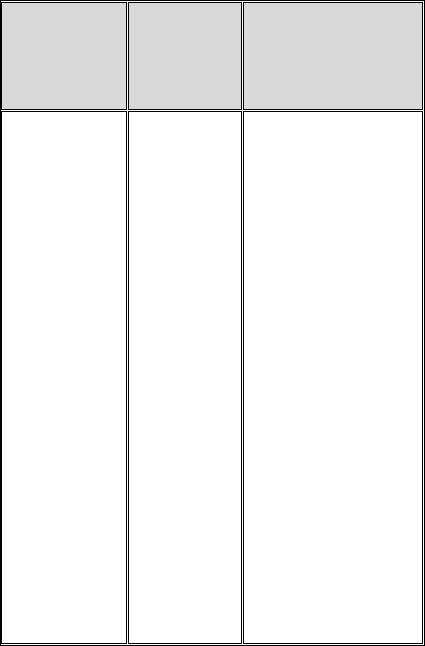

Table 1 summarises the results and conceptual

relationships that arose from the analysis.

As one respondent pointed out that the transfer of

tacit knowledge is ‘a pretty tough gig. It’s a tough,

tough call and it’s easier said than done.’ This

interviewee also commented that

‘I don’t believe

they’ve (the university) got a formal strategy for

transfer of tacit knowledge.’

The findings resonate with previous studies in

Malaysia, Singapore and UK, which have highlighted

that a knowledge sharing culture exists in tertiary

educational institutions however challenges such as

motivation, lack of reward mechanisms, knowledge

hoarding, dearth of open-mindedness and inadequate

support and encouragement from leaders exist (Wah

et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2009; Fullwood et al., 2013;

Goh and Sandhu, 2013).

Universities are places

where the transfer of tacit knowledge should be the

primary mission but as the analysis demonstrates

there are anecdotes in which the elicitation,

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

132

Table 1: Results and conceptual relationships.

Repeating

Ideas

Theme

Recommendations

-General

agreement

that

universities

encourage and

facilitate tacit

knowledge

sharing.

-Lack of open

communicatio

n.

-Untrusting

work

environment.

-Manager’s

reluctance to

share

knowledge

(seen as

information

gatekeepers).

-More

encouragem

ent and

support to

share tacit

knowledge

is required

to

counteract

the

identified

issues.

-Tacit knowledge

should be valued.

-Develop

transformational

leaders.

-Nurture a

trustworthy work

environment.

-Managers to play an

active role in

practicing and

promoting open

communication.

distribution and reuse of tacit knowledge seems to be

difficult (especially those involving university

managers). Moreover, this appears to be a general

perception valid outside Australia too.

Although the respondents were generally very

positive about the universities encouraging and

facilitating the sharing of professional experiences,

skills and knowledge with others however there are

evident areas which require improvement. Some of

the areas identified are: building a tacit knowledge

sharing culture, promoting open communication and

sharing of ideas, developing inspirational

transformational leadership, establishing a team-

working culture, and encouraging ways of promoting

peer-trust. It can be argued from a systemic

perspective that changes need to be made to

encourage the transfer of tacit knowledge in

universities.

Hence, the general notion was that most

universities provide a mixture of facilitating

conditions however there are areas of improvement.

To conclude this section, the words of an interviewee

are quoted who very aptly said ‘The whole purpose of

an educational institution is to spread knowledge -

that is the fundamental purpose of educational

institutions. So the ethos should be exactly the same,

otherwise subconsciously the people you are teaching

will learn as if information is to be hidden.’

5 CONCLUSIONS

The epistemological discourse in the study has found

that it is not all doom and gloom for tacit knowledge

transfer in Australian universities. The findings were

generally upbeat as universities encourage the

transfer of tacit knowledge although some areas for

further improvement have been identified. The

findings will assist universities in further creating a

systematically driven collaborative environment that

encourages the transfer of tacit knowledge and makes

it available for reuse. Given the increased interest in

knowledge management by organisations, such a

study is timely and relevant.

The study has identified a few limitations that

hindered it from obtaining more conclusive results.

As this study was conducted in only four Australian

universities (eight interviews), it is plausible that

larger sample sizes may demonstrate dissimilar

results. Owing to the current small sample size, it

would be deemed inappropriate to generalise the

findings to a larger population. However, like any

exploratory study, this study also provides a picture

of the reality. Despite the limitations, this study is

significant as it further contributes to advancing the

knowledge in a research area by providing researched

evidence and hypothesis, which can be validated later

using other methods. Future studies could validate the

findings and/or carry out quantitative studies that

could be of help to draw more concrete, possibly less

obvious, conclusions. It is also suggested that future

studies look at specific elements such as provision of

adequate time and mentoring programs, which are

seen as enablers of tacit knowledge transfer.

Finally, this paper has made a significant

contribution to tacit knowledge management by

addressing an important question that has largely

been ignored till date. The key contributions of this

study fall into three main areas. Firstly, it has added

to existing research on tacit knowledge transfer.

Secondly, it has used qualitative methods like

interviews to assess whether academics’ workplaces

(universities) encourage the transfer of tacit

knowledge. Thirdly, the findings can be used to make

improvements, develop a culture that promotes

openness and enhance the sharing of tacit knowledge.

Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?

133

REFERENCES

Alvesson, M., 2000, ‘Social identity and the problem of

loyalty in knowledge-intensive companies’, Journal of

Management Studies, vol.37, no. 8, pp.1101-1123.

Bartol, K. and Srivastava, A., 2002, ‘Encouraging

knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward

systems’, Journal of Leadership and Organization

Studies, vol. 19, no. 1, pp.64-76.

Baumard, P., 1999, Tacit knowledge in organisations, Sage

Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Baumard, P. and Starbuck, W.H., 2005, ‘Learning from

failures: Why it may not happen’, Long Range

Planning, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 281-298.

Bechina, A.A.A. and Ndlela, M.N., 2007, ‘Success factors

in implementing knowledge based systems’, Electronic

Journal of Knowledge Management, vol. 7, no. 2, pp.

211-218.

Blair, D.C., 2002, ‘Knowledge management: hype, hope, or

help?’, Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, vol. 53, no. 12, pp.1019-1028.

Busch, P., 2008, Tacit knowledge in organizational

learning, IGI-Global, Hershey.

Cavana, R.Y., Delahaye B.L. and Sekaran, U., 2003,

Applied business research: qualitative and quantitative

methods, John Wiley & Sons, Milton Queensland.

Cepeda, G., 2006, Competitive advantage of knowledge

management, in Schwartz, D.G. (ed.), Encyclopaedia of

Knowledge Management, pp. 34-43, Idea Group

Reference, Hershey.

Cheng, M. Y., Ho, J. S. Y. and Lau, P. M., 2009,

‘Knowledge sharing in academic institutions: a study of

Multimedia university Malaysia’, Electronic Journal of

Knowledge Management, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 313-324.

Chugh, R., 2013, ‘Workplace dimensions: Tacit knowledge

sharing in universities’, Journal of Advanced

Management Science, vol. 1, no.1, pp.24-28.

Chugh, R., Wibowo, S. and Grandhi, S., 2014, Should

transfer of tacit knowledge be made mandatory?, in

Proceedings of the 24th International Business

Information Management Conference (IBIMA 2014),

November 6-7, 184-192, Milan, Italy.

Clayton, B. and Fisher, T., 2005, ‘Sharing critical ‘know-

how’ in TAFE Institutes: benefits and barriers’,

AVETRA 8th Annual Conference: Emerging Futures -

recent, responsive & relevant research, 13 - 15 April,

Brisbane, pp. 1-11.

Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, L., 1998, Working knowledge:

how organizations manage what they know, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston.

DeLong, D.W., 2004, Lost knowledge: confronting the

threat of an aging workforce, Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

DeLong, D.W. and Fahey, L., 2000, ‘Diagnosing cultural

barriers to knowledge management’, Academy of

Management Executive, vol.14, no. 4, pp.113-127.

Empson, L., 2001, ‘Introduction: knowledge management

in professional service firms’, Human Relations,

vol.54, no. 7, pp. 811-817.

Flick, U., 2006, An introduction to qualitative research, 3rd

edition, Sage publications, Oxford.

Foos, T., Schum, G. and Rothenberg, S., 2006, ‘Tacit

knowledge transfer and the knowledge disconnect’,

Journal of Knowledge Management, vol. 10, no. 1, pp.

6-18.

Frappaolo, C. and Wilson, L.T., 2003, After the gold rush:

harvesting corporate knowledge resources. Intelligent

KM, viewed 2 April 2015,

http://www.intelligentkm.com/feature/feat1.shtml.

Fullwood, R., Rowley, J. and Delbridge, R., 2013,

‘Knowledge sharing amongst academics in UK

universities’, Journal of Knowledge Management, vol.

17, no.1, pp. 123-136.

Geuna, A. and Muscio, A., 2008, The governance of

university knowledge transfer, SPRU Electronic

Working Paper Series, Paper No.173, University of

Sussex, pp.1-29.

Goh, S. K. and Sandhu, M. S., 2013, ‘Knowledge sharing

among Malaysian academics: influence of affective

commitment and trust’, The Electronic Journal of

Knowledge Management, vol.11, no.1, pp. 38-48.

Gummesson, E., 2000, Qualitative methods in management

research, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Hislop, D., 2009, Knowledge management in

organizations: a critical introduction, 2nd edition,

Oxford University Press, New York.

Housel, T.J. and Bell, A.H., 2001, Measuring and

managing knowledge. McGraw-Hill Irwin, Boston.

Jain, K. K., Sandhu, M. S. and Sidhu, G. K., 2007,

‘Knowledge sharing among academic staff: a case

study of business schools in Klang Valley, Malaysia’,

Journal for the Advancement of Science & Arts, vol. 2,

pp. 23-29.

Karlsen, J.T. and Gottschalk, P., 2004, ‘Factors affecting

knowledge transfer in IT projects’, Engineering

Management Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 3-10.

Laupase, R., 2003, Rewards: do they encourage tacit

knowledge sharing in management consulting firms?

Case studies approach, in Coakes. E. (ed.), Knowledge

Management: Current Issues and Challenges, pp. 92-

103, Idea Group Inc, Hershey.

Liebowitz, J. and Chen, Y., 2003, Knowledge-sharing

proficiencies: The key to knowledge management, in

Holsapple, C.W. (ed.), Handbook on Knowledge

Management 1: Knowledge Matters, pp. 409-424,

Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Lin, H. and Lee, G., 2004, ‘Perceptions of senior managers

toward knowledgesharing behaviour’, Management

Decision, vol. 42, no. 1, pp.108-125.

Lincoln, Y.S. and Guba, E.G., 1985, Naturalistic inquiry,

Sage, Beverly Hills.

Loermans, J., 2002, ‘Synergizing the learning organization

and knowledge management’, Journal of Knowledge

Management, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 285-294.

Muralidhar, S., 2000, Knowledge management: a research

scientist’s perspective, in Srikantaiah, T.K. and M.E.D.

Koenig (eds.), Knowledge Management for the

Information Professional, ASIST Monograph Series,

Information Today, Medford.

Nesan, J., 2012, ‘Factors influencing tacit knowledge in

KMIS 2015 - 7th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

134

construction’, Australasian Journal of Construction

Economics and Building, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 48-57.

Nonaka, I., 1994, ‘A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation’, Organization Science, vol. 5, no.

1, pp.14-37.

Nonaka, I., von Krogh, G. and Voelpel, S., 2006,

‘Organizational knowledge creation theory:

evolutionary paths and future advances’, Organisation

Studies, vol. 27, no. 8, pp.1179-1208.

O’Dell, C., 2002, Knowledge management new generation,

presented at the APQC’s 7th Knowledge Conference,

Washington DC.

Onwuegbuzie, A.J. and Leech, N.L., 2007, ‘Sampling

designs in qualitative research: making the sampling

process more public’, The Qualitative Report, vol.12,

no. 2, pp. 238-254.

Pan, S.L. and Scarbrough, H., 1999, ‘Knowledge

management in practice: An exploratory case study’,

Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol.11,

no.3, pp. 359-374.

Parlby, D. and Taylor, R., 2000, The power of knowledge:

a business guide to knowledge management, viewed 2

April 2015, www.kpmgconsulting.com/index.html.

PhillipsKPA, 2006, Knowledge transfer and Australian

universities and publicly funded research agencies, A

report to the Department of Education, Science and

Training, viewed 2 April 2015,

http://apo.org.au/research/knowledge-transfer-and-

australian-universities-and-publicly-funded-research-

agencies.

Prusak L., 2006, Foreword, in Schwartz, D.G. (ed.),

Encyclopaedia of Knowledge Management, Idea Group

Reference, Hershey.

Miller W., 1996, Capitalizing on knowledge relationships

with customers, in Proceedings of Knowledge

Management ’96, Business Intelligence Inc, London.

Riege, A., 2007, ‘Actions to overcome knowledge transfer

barriers in MNCs’, Journal of Knowledge

Management, vol. 11, no. 1, pp.48-67.

Seba, I., Rowley, J and Delbridge, R., 2012, ‘Knowledge

sharing in the Dubai police force’, Journal of

Knowledge Management, vol.16, no.1, pp. 114-128.

Smith, E.A., 2001, ‘The role of tacit and explicit knowledge

in the workplace’, Journal of Knowledge Management,

vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 311-321.

Subramaniam, M. and Venkatraman N., 2001,

‘Determinants of transnational new product

development capability: testing the influence of

transferring and deploying tacit overseas knowledge’,

Strategic Management Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, pp.359-

378.

Sveiby, K.E., 1997, The new organizational wealth:

managing and measuring knowledge- based assets,

Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco.

Swart, J. and Kinnie, N., 2003, ‘Sharing knowledge in

knowledge-intensive firms’, Human Resource

Management Journal, vol.13, no. 2, pp. 60-75.

Vera, D. and Crossan, M., 2004, ‘Strategic leadership and

organization learning’, Academy of Management

Review, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 222-240.

Wah, C. Y., Menkhoff, T., Loh, B. and Evers, H., 2007,

‘Social capital and knowledge sharing in knowledge-

based organizations: an empirical study’, International

Journal of Knowledge Management

, vol. 3, no. 1, pp.

29-48.

Do Australian Universities Encourage Tacit Knowledge Transfer?

135