A Survey on Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes from

the Perspective of Knowledge Management

Christoph Sigmanek and Birger Lantow

University of Rostock, 18051 Rostock, Germany

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Business Process Oriented Knowledge Management, Knowledge-intensive

Processes, Process Modelling.

Abstract: Existing modelling approaches for knowledge-intensive business processes try to match the character of

these processes by specific modelling concepts and methods. The approaches differ significantly depending

on the focus of modelling. DeCo and KIPN for example recommend to be less strict on control flow

orientation. KMDL allows for modelling down to the level of individuals. SBPM and KPR as well

emphasize a detailed model and additionally underline the importance of distributed modelling. GPO-WM

in contrast suggests avoiding too much details. However, which approach or what level of abstraction is

now suitable for which modelling task from the perspective of knowledge management? Can the models be

reused for other tasks? The search for the "right" way for modelling knowledge-intensive processes and

issues derived therefrom are in the focus of discussion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, knowledge is recognized as an important

enterprise resource. Thus, knowledge management is

derived as a management task. Here, business

process oriented knowledge management aims at the

ways of dealing with knowledge and requirements

for knowledge and knowledge activities (use,

production, and transfer of knowledge) in business

processes. Remus puts knowledge-intensive business

processes in the focus of a process-oriented

knowledge management (Remus, 2002, p.108). Here

lies the biggest success potential for knowledge

management. Table 2 summarizes the typical

characteristics of knowledge-intensive processes.

They are commonly found in knowledge-intensive

domains and are characterized by a high degree of

complexity. Control flow varies widely, so that a

high coordination and communication effort is

required. Knowledge-intensive processes are often

poorly structured, show a high number of

participants (experts), and are difficult to plan. Due

to their nature, it is difficult to reassign tasks to

different individuals (Remus, 2002, pp. 104-117).

Heisig sees as the most relevant criterion of

knowledge-intensive processes that required

knowledge can be planned ahead only in a limited

manner (Heisig, 2002).

In order to model the knowledge support of

processes, it is no longer sufficient to restrict the

process to a sequence of activities, events and

decisions consequently. Rather, it is necessary that

important components from the perspective of

knowledge management can be presented and that

the modelling methodology fits to the special

characteristics of these processes.

Considered to model components are:

1. Knowledge activities

a. Knowledge creation and knowledge use

(Allweyer, 1998, pp. 165)

b. Knowledge transfer

2. Knowledge resources

a. Knowledge carriers (Allweyer, 1998, pp.

165)

b. Knowledge sources

3. Knowledge Structure Conditions

a. ICT-involvement, the tech-nologies used

(Scheer, 1998, pp.63-65)

b. Organisational requirements and corporate

culture (Lehner et al., 2007)

On the same hand, the high complexity and

variability of knowledge-intensive processes has to

be considered by the modelling methodology.

In business processes, activities are performed in

Sigmanek, C. and Lantow, B..

A Survey on Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes from the Perspective of Knowledge Management.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 325-332

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

325

a logical sequence by individuals who act in roles.

For the successful completion of knowledge-

intensive tasks the individuals must satisfy their

need for knowledge with the help of knowledge

activities. Here, they interact more or less efficiently

through various media with other people and IT

systems. During these interactions new knowledge is

generated constantly. However, it can only partly be

preserved. In order to transfer these processes into a

model, a structured approach is needed, which

selects a proper level of detail. Since good models

represent an appropriate part of the real world, it is

possible to draw an analysis on how processes can

be improved in the real world based on these

models. Furthermore, the modelling provides the

advantage that knowledge about business processes

can be documented and shared. In the following

section, state-of-the-art methods to collect and

analyze knowledge-intensive business processes are

presented. They should ensure a correct model of

implicit and explict knowledge. The third section

then provides an evaluation of the presented

approaches in relation to the initially formulated

modelling requirements. The final section

summarizes the found open challenges for modelling

knowledge-intensive processes.

2 APPROACHES TO

MODELLING AND ANALYSIS

OF KNOWLEDGE-INTENSIVE

BUSINESS PROCESSES

In the literature there is a variety of approaches to

modelling knowledge-intensive processes and

modelling of knowledge management aspects in

process models.

This section discusses a selection. A part of

approaches has been selected based on an analysis of

the citation (> 50 citations in Google Scholar). Thus

a high scientific impact can be assumed.

Additionally, DeCo and KIPN (> 10 citations) have

been selected, which have been published more

recently. They do not have a comparable citation

count. However, we assume that the limited

timeframe is the major reason for that. Thus we

discuss well established approaches (>50 citations)

and current trends and ideas (DeCo and KIPN).

2.1 Knowledge Modelling and

Description Language

The Knowledge Modelling and Description

Language (KMDL) is a method for modelling

knowledge-intensive business processes that is still

Table 1: Attributes of knowledge-intensive processes according to Remus (2002).

Attribute class Typical attribute values of knowledge intensive processes

Process independent attributes

(knowledge intensive domain)

often decentralized networking organization showing a goal oriented support of

knowledge transfer, e.g. by incentives

Knowledge intensive domain (key technologies)

Complex relations between processes

Attributes concerning the process

(variablility)

Complex processes having many dependent single activities, actors that work in

interdisciplinary teams

Many exceptions, unpredictable control flow and results

Poorly structured, only ex-post modelling possible

High coordination and communication effort between the actors, needs knowledge

from different domains

Generating knowledge-intensive products and services

Only imprecise controlling possible, often qualitative goals

Low number of process instances having long running times

Process case driven, no standard process

Attributes concerning tasks (poor

transferability)

Productivity of knowledge work usually not measurable

Long learning and and training periods necessary

Chaotic workplace

Tasks are communication oriented, require a lot of information, case driven

Typical tasks are: decision making, problem solving, analysis and evaluation,

controlling and management

Attributes concerning actors (experts)

Highly autonomous actors

Unstructured and individualized rules and routines

High competency, learning aptitude, creativity and innovation required

Attributes concerning resources

(complex resources)

Wide use of knowledge management instruments, informal knowledge transfer

Knowledge often hardly accessible and highly depending on the context

High amount of handled knowledge, cost intensive knowledge acquisition.

RDBPM 2015 - Special Session on Research and Development on Business Process Management

326

under active development. (Gronau, 2009, pp. 76-

79) (KMDL, 2014).

KMDL is distinct from other approaches due to

its person or individual related knowledge

modelling. Here, the method provides an explicit

modelling of individual knowledge conversions as

introduced by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995). In

addition, the method provides various analysis views

and comparative patterns for analysis.

The KMDL method is based on a nine-phase

process model. The active participation of the

project partner is required for successful knowledge

management projects. First, in phase 0 the

organizational framework is set. In Phase 1, the

definition of the intended objectives of the project

follows. Then, in Phase 2, the processes of the

project partner are iteratively registered, refined and

validated. This is the base for deriving knowledge

intensive processes in phase 3. In Phase 4 these

knowledge-intensive processes are iteratively

modelled and sequentially analysed for possible

improvements in phase 5. Specifically, the focus lies

on finding weaknesses in order to derive suggestions

for improvement from them. Then they are classified

and evaluated, and finally there is an assessment of

the potential for improvement. In the following 6

th

phase to-be concept is developed with the partners,

which will be implemented in phase 7. In the final

phase 8 the whole process will be evaluated together

with the project partner. (Gronau, 2009, pp.75)

KMDL defines three views for the different

requirements of modelling knowledge-intensive

processes. The process view shows the business

processes at an abstract level. Here, individual

activities are displayed in their logical order in

conjunction with the involved resources. Activities

are broken down to knowledge transformations (e.g.

socialization) in the activity view. The activity view

is also the basis for the communication view, which

describes how individual knowledge transformations

are performed in conversations. Conversations are

characterized by location (the same location /

different location) and time (synchronous /

asynchronous). (Pogorzelska, 2009, pp. 21-45)

KMDL analysis is based on these models. In the

first analysis the frequencies of knowledge objects

and conversation types (e.g. socialization) are

counted and evaluated accordingly. A high number

of socialization activities may for example indicate

that too little knowledge is explicated. A recurring

knowledge resource or a person who is involved in

many activities in contrast may point to a possible

bottleneck or a key function. Thus, knowledge needs

are matched with knowledge services, and there is

an assessment of the models regarding specific

patterns. There are concrete improvement actions

indicated for each pattern. (Pogorzelska, 2009, pp.

49-79)

KMDL provides a holistic approach to modelling

and improvement of knowledge-intensive processes.

For modelling with KMDL, the tool K-Modeler (K-

Modeler, 2014) is available. The method has been

criticized for the extra effort that is induced by the

collection of the individual knowledge

transformations. It can only be justified by better

coverage of improvement measures for knowledge

management (Krallmann et al., p 417). Thus, this

method is very time consuming and the results

strongly depend on the trust of the interviewees and

the skills of the interviewer (Müller et al., 2012,

pp.362).

2.2 Knowledge Process Reengineering

The Knowledge Process Reengineering (KPR)

approach (Allweyer, 1998, pp.163- 168) is a seven-

step approach to improve the handling of the

resource "knowledge". In particular, the approach

aims at effective knowledge sharing, good

documentation and easy access to knowledge. KPR

was developed for use in enterprises and can be

supported by ARIS models. The individual phases,

starting with the strategic knowledge planning,

going on about the actual analysis and target

conception, to implementation, run linearly in KPR.

Re-entering a completed phase is not considered.

Instead, the approach provides an ongoing testing

and improvement process in the final phase.

KPR starts with strategic knowledge planning.

Here is determined how knowledge management can

support the company's strategic objectives. Models

which relate the core business processes to the

strategic business objectives help in this phase.

Subsequently, an as-is modelling of knowledge

usage and transformation is performed. The KPR

approach uses EPC for process description due to its

tight coupling to ARIS. Then knowledge carriers,

knowledge categories and knowledge needs must be

captured in knowledge structure diagrams,

knowledge maps and additional information in the

EPC diagrams. (Allweyer, 1998, pp.164-166)

Once the as-is situation has been modelled, its

analysis begins. Here, critical knowledge

monopolies, unsatisfied knowledge needs,

inadequate knowledge profiles of employees etc. are

revealed. The following development of a to-be

concept for knowledge handling provides measures

to solve the previously found issues. This is done for

A Survey on Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes from the Perspective of Knowledge Management

327

example, by target knowledge profiles for

employees or changes in business processes. After

the to-be concept is set, realisation concepts for the

organisation and the ICT are developed. The

realization concept regarding the organisation

includes staff trainings regarding new processes and

new IT systems. The ICT realization concept

includes the selection of appropriate IT solutions,

the definition of content structures and system

integration.

After implementing the to-be concept by the

developed realization concepts, a phase of testing

and possibly improving starts. (Allweyer, 1998,

pp.166-168)

KPR thus offers an approach, which aims to

anchor technologies of knowledge management in

the working procedures of employees. The strong

dependence on the underlying ARIS architecture, the

requirement to model all the knowledge of a

company, and the lack of a detailed description of

single method steps are critical issues of KPR. In

consequence, KPR is only a specific process model

for the integration of IT in knowledge-intensive

business processes.

2.3 PROMOTE

Hinkelmann et al., (2002, pp. 65-68) presented with

process-oriented methods and tools for knowledge

management (PROMOTE) a technology-

independent method for the management of

functional and process knowledge. It is an evolution

of the business process management system

framework (BPMS) (Karagiannis, 1995) and

supplements this by the software tool PROMOTE

(BOC, 2014). PROMOTE focuses on the

identification, modelling and integration of

processes that require and generate knowledge. The

software supports the processing of knowledge-

intensive activities by knowledge processes can be

activated context-specific. Furthermore, it provides

knowledge maps and topic maps as configurable

knowledge management tools and. Finally,

PROMOTE provides management capabilities for

knowledge flows and a model-based indexing of

documents with process- and role-specific access

rights.

As a prerequisite for the approach, the following

assumptions are made:

1. Knowledge processes can be modelled the same

way as business processes

2. Activities in business processes use knowledge.

Base for the use of PROMOTE the method steps

which provide high degree of freedom. Depending

on the context the order of these steps and the final

results may vary. The general goal is a support of

knowledge flows between knowledge-intensive

business processes. This knowledge flows can occur

within a business process, across business processes,

within a project, and even across projects. In

addition, external knowledge inflows by training,

internet research, etc. are possible. (Hinkelmann et

al., 2002, pp. 68-71)

Realization is done in the five phases “Aware

Enterprise Knowledge”, “Discover Knowledge

Process”, “Modelling Knowledge Processes and

Organisational Memory”, “Making Knowledge

Processes and Organisational Memory operational”

and “Evaluate Enterprise Knowledge”. In the first

phase corporate goals are adjusted and strategically

determined. These are for example products,

services, financial requirements and the

development of core competencies. The aim is an

alignment of the knowledge strategy with the

business strategy. (Hinkelmann et al., 2002, S. 73-

76)

In the ensuing “Discover Knowledge Process”

phase process knowledge is modelled. That means

knowledge of the logical sequence of activities

within a process, including participating

organizational units, application systems and

resources. In addition, knowledge with high

potential impact is identified by experts. This

includes decision-critical knowledge and knowledge

to create a service or a product (functional

knowledge). In addition, types of processed

knowledge, knowledge carriers, knowledge flows

and the forms of knowledge representation are

recorded. After the modelling of business processes

modelling and mapping of knowledge processes

takes place in the third phase. Knowledge processes

should replace knowledge flows by giving the

knowledge flow a methodology. If an agent requires

knowledge to carry out a task, then there are

different options to obtain this knowledge. For

example, he can turn to his colleagues or look up an

expert using yellow pages. To make documents

retrievable and therefore available for future use,

they are enriched with metadata. A document gets a

modification date, content keywords (tags) from

folksonomies (collections of tags), an author and

other information that are ideally already set by the

appropriate knowledge structures and form the

technical part of the organizational memory.

(Hinkelmann et al., 2002, pp. 76-84)

Phase 4 “Making Knowledge Processes and

Organisational Memory operational” implements

these knowledge processes in existing software.

RDBPM 2015 - Special Session on Research and Development on Business Process Management

328

Hence, during his work an agent can see

immediately which options he has to satisfy his

knowledge needs. For example, a direct link to

yellow pages for expert search can be provided,

having context specific search parameters already

set. An evaluation of the use of PROMOTE takes

place in the 5th phase. Thus, the contribution of

knowledge management can be measured by the

success of the company. (Hinkelmann et al., 2002,

pp. 84-90)

2.4 Declarative Configurable

Declarative Configurable (Deco) is a combination of

declarative modelling, model verification and

variability modelling to capture knowledge-intensive

processes. In DeCo, the knowledge-intensive

processes are modelled on three layers. The most

abstract layer is at design. Here, a configurable,

nondeterministic specification is created in

accordance with the process goals. In the at-

deployment layer, the process is configured in a

context that is close to the application domain.

Finally, a fully deterministic process execution trace

that maps a single process instance is created in the

at execution layer. (Rychkova and Nurcan, 2011, pp.

1-2)

Business processes are divided into prescriptive

processes and descriptive processes. Prescriptive

processes have predictable process flows, simple

tasks, and can be fully specified at design time. At

the opposite pole are the descriptive processes,

which include the knowledge-intensive processes.

.These complex tasks are based on cooperation

between different actors, can only be outlined at

design time. Principles underlying DeCo are: "Very

little is certain at design-time" and "Fixed constraint

often means lost opportunities". Therefore, nor

control flow is required in the at-design layer for

descriptive processes. Thus, the configurability

remains unlimited and critical decisions can be made

later on. (Rychkova and Nurcan, 2011, pp. 2-5)

Processes are configured in a specific context in

the at-deployment layer in order to allow

implementation for a certain application. Some

details may not be pre-configured because of their

vagueness. For configurable processes tasks are

assigned to roles, tasks are arranged or selected rules

are applied for example. In the at-execution layer,

the pre-configured processes are finally carried out,

leaving process tracks that are stored and thus

contribute to the construction of a knowledge base

and contribute to improving future processes.

(Rychkova and Nurcan, 2011, pp. 2-9)

Hence, DeCo helps with the controlled assembly

of important process specifications from predefined

process parts or process variants. The design phase

is controlled by central questions and after each

execution possible new paths are incorporated in the

initial or adapted model. The DeCo notation is an

adaptation ofthe BPMN standard: Optional objects

are marked by dashed lines, configurable objects by

bold lines. Furthermore, objects are enriched by tags

(e.g. <IN> for detailed information) in order to

describe knowledge-intensive processes. Mainly the

variability of knowledge-intensive processes is

covered by this approach. (Rychkova and Nurcan,

2011, pp. 5-10)

2.5 GPO WM

Heisig (2002, pp. 47-59) shows with "Business

Process Oriented Knowledge Management" (GPO-

WM) is an eight-phase model for the introduction of

knowledge management. Furthermore, the

company’s strengths and potentials related to the use

of the resource "knowledge" can be determined.

Important paradigms of GPO-WM are:

1. There should not be too much details in the

models.

2. There should be a close connection between the

method expert and the organization.

One possibility to keep a close connection to the

organisation that is subject to a GPO-WM project

could be the use of a company-specific modelling

language. In order to put the focus on relevant tasks

and processes, the central question “Does the task

contain base activities of knowledge management?”

is proposed. Basic tasks of knowledge management

are generating knowledge, storing knowledge,

transferring knowledge and applying knowledge.

During analysis, the focus is not on optimizing

particular activities such as storing explicit

knowledge in a database, but rather on consideration

of the entire frame. Hence, questions like “Where is

the generated knowledge reused?” are in the focus.

Problems are identified based on guiding questions

and possibly solved by best-practice solutions for

knowledge management. Thus, problems can be

discovered, which are not shown in a model. As a

result, knowledge management modules are

implemented and integrated into the respective

business processes. (Heisig, 2002, pp. 59-64)

2.6 KIPN

França et al., (2012) noted that there are already

numerous methods for modelling knowledge-

A Survey on Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes from the Perspective of Knowledge Management

329

intensive processes and examine to what extent these

can map knowledge-intensive processes regarding

their specific process characteristics. Like Gronau

(2009, pp. 69-71) in a similar study, they conclude

that no approach from the literature covers all

relevant aspects. França et al. made a step further

and examined already established process modelling

languages such as BPMN and EPCs based on the

same criteria. It revealed that EPCs and BPMN

already meet many of the requirements for the

modelling of knowledge-intensive processes as

defined by Remus (Remus, 2002, pp 115-116).

Shortcomings are in the representation of poorly

structured processes, the relationships to other

business processes, knowledge transfer and the short

half-life of knowledge.

As a result, França et al. propose an ontology

(KIPO) for knowledge-intensive processes (França

et al., 2012, pp 499-504) as the basis of the

Knowledge Intensive Process Notation (KIPN).

KIPN is a graphical notation which is composed of

five diagrams. In the KIP diagram, activities are

represented including business rules, relations and

the level of abstraction. Modelling the control flow

of individual activities is not mandatory in KIP

diagrams. Communication between the actors, i.e.

exchanged messages, knowledge acquisition and

knowledge transfer, are shown in the socialization

diagram. Finally, alternatives and their advantages

and disadvantages are listed in a decision diagram.

In addition, the notation provides diagrams for goal

and for role modelling (França et al., 2013).

3 REVIEW OF THE PRESENTED

APPROACHES

In the previous section, different approaches to

handle knowledge-intensive business processes have

been introduced. In the various approaches it is clear

that knowledge-intensive processes need to be

treated differently from normal processes due to

their nature. All authors claim that setting the right

focus of modelling is crucial for the output of an

analysis. DeCo and KIPN recommend to diverge

from the control flow orientation of many modelling

languages. An alignment of knowledge or corporate

objectives respectively is the starting point of any

modelling or analysis project. KMDL provides the

ability to model on the level of individuals and

requires a strong incorporation of the modelled

organisation in the modelling process. This results in

a very context specific model which might not be

transferable and might have limited maintainability

due to the variability of knowledge-intensive

processes as described in DeCo.

KPR recommends a distributed modelling. Due

to a separate specification of concepts on one hand

and concurrent activities at the other hand, semantic

consistency can be guaranteed throughout the model.

For both - distributed modelling as well as a

modelling in a central model – several modelling

phases are proposed. In some approaches, the

detailed modelling has a high priority for subsequent

analysis, while GPO-WM discourages too high

detailing. Most methods solve identified problems

by the introduction of concrete knowledge

management tools and their integration into the

business processes. GPO-WM provides best

practices that cover certain problem categories. The

variety of objectives led to a multitude of different

modelling languages. However, none of them was

able to prevail in the literature to date.

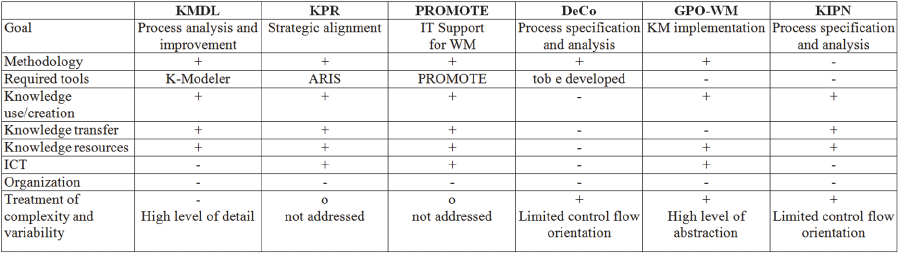

Table 2 presents the main features of each

approach in a summary. The idea is to provide a

starting point for the selection of an existing

approach depending on the modelling requirements.

Furthermore, the limitations of existing should be

emphasized.

Table 2: Characteristics of the approaches.

RDBPM 2015 - Special Session on Research and Development on Business Process Management

330

In rows 1-3, general modelling aspects such as

goals, methodological support and required tools are

taken into account. These information can be used to

assess the practical applicability. First, the goal of

the modelling approach must fit to the goals of the

modelling project. Key point is the project focus - is

it a process improvement cycle on operational level

or is it a strategic alignment? Furthermore, a

modelling methodology as well as an appropriate

toolset should be provided for the applicability of an

approach.

The rest of the table addresses the specific

requirements of modelling knowledge-intensive

processes from Section 1 by a meta-analysis. Thus,

the approaches are matched against the theory of

knowledge intensive processes. Necessary modelling

artefacts are identified and the existence of

respective modelling constricts in the several

approaches is assessed. Regarding knowledge

activities (rows 4-5), there is a distinction between

knowledge use/generation and the representation of

knowledge transfers, because the latter is not

covered by all approaches while generally all

approaches address knowledge use and generation.

A supplement to this is then the modelling of

knowledge resources and their structures (row 6).

The possibility of taking into account the technical

infrastructure (ICTs) and organizational

environment is considered in rows 7-8. The last row

of the table aims at the ways how the approaches are

dealing with the complexity and variability in the

knowledge-intensive processes.

One result of the investigations is that all

approaches fail to describe the organizational

environment regarding knowledge intensive

processes. Additionally, only two address the

modelling of knowledge management system

components in terms of ICT support (KPR, GPO-

WM). Knowledge activities and knowledge

resources on the other hand are well covered. Thus,

the latter might be a starting point for model reuse in

different contexts because they are present in the

approaches independently from the defined goals.

4 CONCLUSION

Gai & Dang name three limitations of the process-

oriented knowledge management (Gai and Dang,

2010, pp. 3-4):

1. Not all knowledge activities are associated with

business processes. An example is the desire to

communicate during a coffee break.

2. The variability of the processes is not well

represented by many methods. Knowledge flows

are changing and are not tied to static processes.

3. Tacit knowledge is often treated inadequately.

Knowledge carriers are modelled as an attribute,

but this is not enough to represent the flow of

knowledge.

Limitation 1 generally applies to the approach of

business process-oriented knowledge management.

The context, in particular the organizational

conditions have a significant impact on the

performance of knowledge-intensive processes. This

applies not only to knowledge activities performed

outside the processes. The modelling approaches do

not take this into account (see table 2). However, the

context should be addressed in the models. The

limitations 2 and 3 are only partially addressed too.

As shown in table 2, not all of the approaches

explicitly model the different possibilities of

knowledge transfer. For dealing with the complexity

and variability of knowledge-intensive processes

two basic ways are being sought of: first, turning

away from the control flow orientation and second a

high abstraction level. It turns out that strategically

oriented modelling approaches (GPO-WM, KPR)

rely on a high level of abstraction, while approaches

to detailed specification and analysis of processes

(Deco, KIPN) have just little control flow

orientation. Besides this straight forward distinction,

guidelines for the application of particular method

components need to be developed: Which approach

fits best to what goals? How can the developed

models be the base for a sustainable knowledge

management? How can the effort and the benefits of

the approaches be evaluated?

In summary, there are only ideas and assistance

for addressing knowledge transfers in process-

oriented knowledge management, but not a complete

methodology. In a lot of cases, the consideration of

process variability, of the organizational

environment and a concrete methodology are

missing. Furthermore, effort and benefits of

knowledge management activities are poorly

addressed.

REFERENCES

Allweyer, T.: Wissensmanagement mit ARIS-Modellen.

In: Scheer, A.-W.: ARIS - vom Geschäftsprozeß zum

Anwendungssystem, 3. Auflage, Springer Verlag,

Berlin 1998, S. 162-168.

BOC Group: Wissensmanagement mit PROMOTE,

http://www.boc-group.com/de/landing-pages/wissens

management-mit-promoter/, (date of access:

A Survey on Modelling Knowledge-intensive Business Processes from the Perspective of Knowledge Management

331

22.12.2014).

França, J. B. S., Baião, F. A., Santoro, F. M.: Towards

Characterizing Knowledge Intensive Processes. In:

Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 16th International

Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative

Work in Design, 2012, p. 497-504.

França, J.B.S., Baião, F.A., Santoro, F.M.: A Notation for

Knowledge-Intensive Processes. In: Proceedings of

the 2013 IEEE 17th International Conference on

Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design,

2013, p. 190-195.

Gai, Y., Dang, Y.: Process-oriented Knowledge

Management: a Review on Strategy, Content, Systems

and Processes. In: IEEE International Conference on

Management and Service Science (MASS), August

2010.

Gronau, N.: Wissen prozessorientiert managen: Methode

und Werkzeuge für die Nutzung des

Wettbewerbsfaktors Wissen in Unternehmen,

Oldenbourg, Munich 2009.

Gronau, N., Müller, C., Uslar, M.: The KMDL Knowledge

Management Approach: Integrating Knowledge

Conversions and Business Process Modelling. In:

Karagiannis, D., Reimer, U.: Practical Aspects of

Knowledge Management. 5th International

Conference, PAKM 2004, Vienna December 2004.

Heisig, P.: GPO-WM: Methode und Werkzeuge zum

geschäftsprozessorientierten Wissensmanagement. In:

Abecker et al.: Geschäftsprozessorientiertes

Wissensmanagement, Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2002, p. 47-64.

Hepp, M., Roman, D.: An Ontology Framework for

Semantic Business Process Management. In:

Proceedings of Wirtschaftsinformatik 2007, Karlsruhe

Februar - März 2007.

Hinkelmann, K., Karagiannis, D., Telesko, R.:

PROMOTE: Methodologie und Werkzeug für

geschäftsprozessorientiertes Wissensmanagement. In:

Abecker et al.: Geschäftsprozessorientiertes

Wissensmanagement, Springer Verlag, Berlin

Heidelberg 2002, S. 65-90.

Karagiannis, D.: BPMS: Business Process Management

Systems. In: ACM SIGOIS Bulletin, New York August

1995/Vol. 16, No. 1, p.10-13.

KMDL Blog, http://www.kmdl.de/ (date of last access:

24.11.2014).

K-Modeler | KMDL Blog, http://www.kmdl.de/

?q=de/node/27 (date of last access: 24.11.2014).

Krallmann, H., Bobrik, A., Levina, O.: Systemanalyse im

Unternehmen: Prozessorientierte Methoden der

Wirtschaftsinformatik, 6. ed., Oldenbourg, Munich

2013.

Lehner, F. et al.: Erfolgsbeurteilung des

Wissensmanagements: Diagnose und Bewertung der

Wissensmanagementaktivitäten auf Grundlage der

Erfolgsfaktorenanalyse. In: Schriftenreihe

Wirtschaftsinformatik, Diskussionsbeitrag W-24-07,3.

ed., Passau 2007.

Müller, C., Bahrs, J., Gronau, N.: Considering the

Knowledge Factor in Agile Software Development. In:

Gronau, N. (Eds.): Modelling and Analyzing

knowledge intensive business processes with KMDL -

Comprehensive insights into theory and practice, Gito,

Berlin 2012.

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H.: The Knowledge-Creating

Company: How Japanese Companies create the

Dynamics of Innovation, Oxford University Press,

New York 1995.

Pogorzelska, B.: Arbeitsbericht - KMDL® v2.2: Eine

semiformale Beschreibungssprache zur Modellierung

von Wissenskonversionen, 07. 01. 2009.

Remus, U.: Prozeßorientiertes Wissensmanagement:

Konzepte und Modellierung. Dissertation, Universität

Regensburg, 2002.

Rychkova, I., Nurcan, S.: Towards Adaptability and

Control for Knowledge-Intensive Business Processes:

Declarative Configurable Process Specifications. In:

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences, 2011.

Scheer, A.-W.: ARIS - vom Geschäftsprozeß zum

Anwendungssystem, 3. ed., Springer, Berlin 1998.

RDBPM 2015 - Special Session on Research and Development on Business Process Management

332