UFO-L: A Core Ontology of Legal Concepts Built from a Legal

Relations Perspective

Cristine Griffo

Ontology & Conceptual Modeling Research Group (NEMO), Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória-ES, Brazil

1 RESEARCH PROBLEM

Computer and Law is a transdisciplinary research

field, which has received increasing attention from

researchers in the past twenty-five years (Bench-

Capon, T. et al, 2012). The problem of presenting

the legal domain has been investigated in different

perspectives by researchers, such as (Stamper,

1977), (Hafner, 1980), and (McCarty 1989), one of

them is the ontological perspective. From NORMA

proposed by (Stamper, 1991) to JudO ontology used

in the Judiciary Framework proposed by (Ceci,

2013) and to LOTED2 proposed by (Distinto et al.,

2014), ontologies have been used as a means of

representing legal concepts. Specifically, there are

some kind of ontologies called legal core ontologies

(LCO), which represent generic legal concepts (e.g.

legal norm, legal fact, and legal relation), usable in

different legal domains. Some examples of legal

core ontologies are: FBO proposed by (Kralingen,

1997), FOLaw proposed by (Valente, 1995), Core

Legal Ontology (CLO) proposed by (Gangemi,

2007), and LRI-Core built by Leibiniz Centre for

Law Research Group (Breuker and Hoekstra,

2004b).

Ontologies are a response for the paradigm shift,

from static data storage in databases disconnected to

Linked Data and Semantic Web (Isotani and

Bittencourt, n.d), (Kuhn et al. 2014). Specifically,

the use of core ontologies in complex domains, such

as the legal domain, allows: 1) the reusability of

generic concepts and semantic interoperability; 2)

the expressiveness gain in languages based on

ontologies, as well as clarity and correctness of the

represented domain (Guizzardi, 2005).

Despite the efforts of researchers in the search

for a computational solution that satisfactorily

represent the legal domain, frequently research has

not taken into account the use of legal theories,

resulting in a gap between the conceptualizations

that are typically considered in the areas of

Computer Science and the study of the Law. In a

preview systematic mapping of the literature on

legal core ontologies, from 128 studies selected, in

the time interval of 1995-2014, we have found out

that only 35 (approx. 27%) used primary sources of

legal theories; 44 studies (approx. 34%) used

indirect sources (e.g. use a LCO based on a legal

theory to build a domain ontology); and 49 studies

(approx. 38%) did not use any legal theory as

primary source (Griffo et al., 2015a).

This gap has been the subject of several papers,

among them, the paper Artificial Intelligence and

Legal Theory at Law Schools written by Gordon

(Gordon, 2005), who suggested the introduction of

an interdisciplinary subject in law schools. Also, in

the paper Ontologies: the Missing link between

Legal Theory and AI & Law, (Valente and Breuker,

1994) ontologies are presented as a missing link

between AI & Law, emphasizing the importance of

using legal theories as basis in Computer and Law

research. Recently, Casanovas (Casanovas, 2012)

wrote about the remaining gap, pointing out the

nature of legal world and the computational

reductionism as causes of this gap. In fact, to

conduct research in a field composed by two distinct

knowledge areas, it is necessary to have a consistent

knowledge of both areas in order to produce suitable

solutions.

If we assume the premise that the use of legal

theories decreases the gap between Computing and

Law, then the next question is: what particular legal

theory should be considered by the ontologist? We

defend, in this Ph.D. proposal, that the choice of a

legal theory must take into account the needs of the

contemporary juridical world. In this sense, the

choice of a legal theory that does not take account

the importance of principles as legal norms will

result in a non-flexible computing solution, distant

from the juridical reality. For this reason, we have

chosen Alexy’s Theory of Fundamental Rights

(Alexy, 2010), (Alexy, 2003) as proposed in (Griffo

et al., 2015b).

Alexy’s theory of Constitutional Rights or

Alexy’s theory of Fundamental Rights addresses

some problems of Legal Positivism by proposing the

(1) Structure of Constitutional Right Norms and the

Griffo, C..

UFO-L: A Core Ontology of Legal Concepts Built from a Legal Relations Perspective.

In Doctoral Consortium (DC3K 2015), pages 13-20

13

(2) Weighing and Balancing structure (Alexy,

2010). The scope of this proposal is the first part of

the Alexy’s Theory, which creates a basis for the

second part.

Under the computational perspective, (Guizzardi,

2005), (Guizzardi et al., 2008), have shown the

consequences of building ontologies (core

ontologies, domain ontologies, application

ontologies) without the use of foundational

ontologies, which are: inconsistency, incorrectness

and incompleteness, denominated in the literature as

quality characteristics (Kececi and Abran, 2001). In

this context, the construction of the LCO proposed

here is based on the Unified Foundational Ontology

(UFO) and propose a new layer for UFO. This layer

(called UFO-L) will represent the generic legal

concepts extracted from selected legal theories as

shown in Figure 1.

The generic concepts existing in UFO will

provide a basis for legal concepts in UFO-L. For

instance, the use of relators, an existing concept in

UFO, will be used to represent legal relations.

According to Guizzardi (Guarino and Guizzardi,

2015) a relator is an objectified relational property

that is existentially dependent on more than one

individuals (e.g. marriage, medical treatment, legal

relation).

Figure 1: Unified Foundational Ontology - UFO

(Guizzardi, 2005) (adapted).

Usually, legal ontologies are built under the

Kelsen’s Pure Theory of Law perspective rather than

a subjective perspective that highlights legal

relations (e.g. FBO, FOLaw, CLO). We propose

removing the focus of legal norms and put it in legal

relations (subjectivist view). As a result, we expect

to achieve a legal core ontology that comes closer

honor the current practice in the area of Law.

With this subjective perspective it is expected to

achieve more flexibility, completeness, and

consistency to model legal domains. Also, it is

expected to decrease modeling costs with the reuse

of generic concepts provided by LCO and decrease

the effort to execute semantic interoperability

between legal domains.

In addition, this research aims to answer the

following questions: Is the use of ontologies

effective to represent the contemporary legal world

from the legal relations perspective? What benefits

does the LCO provide for modeling legal domains?

For this work, we use some legal definitions as

follows.

Norm: A norm is defined as “the meaning of a

normative enunciation” (Alexy, 2010). Norms are

classified as deontological (or legal) norms and

axiological norms. By turn, the deontological norms

are classified as rules and principles. Principles are

optimization requirements, which have different

degrees of satisfaction (degree of fulfillment)

depending on both factual and legal aspects. On the

other hand, rules are norms, which are or fulfilled or

not. (Alexy, 2010).

Legal Relation: is a bond between subjects

achieved by the existence of a legal fact. In other

words, it is the social relation typified in a legal

norm.

Legal Theory: In a simple definition, a legal

theory is a body of systematically arranged

fundamental principles in order to discuss and

describe the ontological problem of law under a

specific perspective.

2 OUTLINE OF OBJECTIVES

The main goal of this thesis proposal is summarized

as follows: We aim to build a legal core ontology

with a relational perspective based on a structural

legal theory of fundamental rights. For this, we will

use Alexy’s Theory (Alexy 2010), (Alexy, 2003), a

contemporary legal theory, to extract the essential

legal concepts and relations in order to contribute for

decreasing the gap between Computer and Law. It is

out of the scope to develop an approach for legal

argumentation (dynamic issues).

Also, to build a consistent ontology and obtain

ontological quality, we will ground the legal core

ontology in a foundational ontology - the Unified

Foundational Ontology (UFO). To achieve this goal,

the following subgoals are considered:

1. To develop a systematic mapping of the

literature on legal core ontologies and a

comparative analysis of the existing legal core

ontologies;

2. To build the legal core ontology (UFO-L layer)

based on UFO as shown in Figure 1;

DC3K 2015 - Doctoral Consortium on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

14

3. To validate UFO-L through empirical experi-

ments with participants from Computer

Science and Law and case study.

3 STATE OF THE ART

The concept of ontology has its origins in

Philosophy (as a field of study and as a system of

categories and their ties). However, in the past 2-3

decades, it has been adapted to Computer and

Information Science to mean frequently a formal

representation of a particular system of categories

and their ties (Guizzardi, 2005), (Guarino, 1998).

From this convergence, Guarino (Guarino, 1998),

Gruber (Gruber, 1995), and Staab (Staab et al.,

2001) propose definitions, methodologies and

classifications of ontologies.

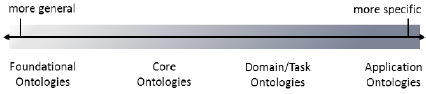

According to Gangemi apud Oberle (Oberle,

2006), ontologies are classified either by their

specificity or by their purpose. Related to specificity,

ontologies are: 1) foundational ontology; 2) core

ontology; and 3) domain ontology. Related to

purpose, ontologies are: 1) reference ontology; and

2) application ontology. Figure 2 shows ontologies

from more specific to more general level.

A foundational ontology defines a set of domain-

independent ontological categories. In turn, a core

ontology defines a set of fundamental concepts of a

field of knowledge (e.g. services, collaboration, law,

organizations, software) that are still general

concepts that occur across multiple domains; core

ontologies are middle-level ontologies often built by

reusing and/or extending a foundational ontology

(Nardi et al., 2013); finally, a domain ontology is

meant to capture a set of concepts from a specific

domain (e.g. Brazilian law). Foundational

ontologies, such as UFO (Guizzardi, 2005) and

DOLCE (Masolo et al., 2003) are useful in building

LCO because they can help to bring both ontological

consistency and completeness to the process. For

instance, the OPJK ontology used concepts as

agent, role, document, process, and act from

DOLCE Lite + CLO, SUMO, and PROTON (apud

Caralt, 2008).

Figure 2: Generality level of ontology as a continuum

(Falbo et al, 2013).

In the literature, the expression “legal core

ontology” began to be used in middle 90’ by Valente

et al (Valente and Breuker 1996), and Breuker et al

(Breuker et al. 1999). Among the most cited legal

core ontologies in the literature are:

Frame-Based Ontology (FBO) proposed by

(Kralingen, 1997), based on legal positivism (Hart,

Kelsen, van Wright, and Ross theories) and written

in Ontoligua. It is a mix of foundational categories

and legal core concepts. The core of this ontology is

the concept of norm and the related concepts of

norm subject, legal modality, and description of the

act.

Functional Ontology of Law (FOLaw)

proposed by (Valente, 1995), written in Ontolingua,

it is based on Kelsen, Hart and Bentham theories,

and has a functional perspective and a knowledge-

perspective (normative knowledge, responsibility

knowledge, reactive knowledge, creative knowledge,

and meta-level knowledge). As this ontology is

based on Kelsen’s theory, basically, norms are only

rules, which are either observed or violated.

Hage and Verheij’s Ontology. Proposed by

(Hage and Verheij 1999), it was written in First-

Order Logic and based on Dworkin and Alexy’s

theories of norms classification (norms are rules and

principles). For them, a legal ontology is an

interconnected dynamic system of state of affairs.

The main categories of this ontology are individuals

(state of affairs, events, and rules) and, similar to

FBO’s ontology, it mixes foundational concepts with

legal core concepts.

Core Legal Ontology (CLO) proposed by

(Gangemi, 2007) and written in OWL-DL, it is the

first LCO that was constructed in a way that it is

grounded in an explicitly defined foundational

ontology (DOLCE).

LRI-core/LKIF-core was built by Leibniz

Centre for Law Research Group (Breuker and

Hoekstra, 2004), , and written in OWL+DL. It is

grounded in different foundational ontologies

(DOLCE, SUO, John Sowa’s ontology). It has later

evolved to LKIF-CORE, which has been built by

the same group (Hoekstra et al., 2007), (Hoekstra et

al., 2009).

PROTON+OPJK is a combination of

ontologies built inside the SEKT European project.

PROTON is a foundational ontology based on

common sense concepts. OPJK (Caralt, 2008) is an

ontology which contains relevant legal domain

specific knowledge. Although, at first sight OPJK

can be considered a legal domain ontology, it also

contains several generic concepts that can be reuse

in different legal domain ontologies (e.g. judicial

UFO-L: A Core Ontology of Legal Concepts Built from a Legal Relations Perspective

15

organization, judicial role), which gives it a flavor of

a core ontology.

NM-L Ontology, coded in Prolog, is a ontology

for legal reasoning proposed by (Shaheed et al.,

2005). It was built as an extension of Naïve

Metaphysics Ontology (NM Ontology) proposed by

(Schneider, 2001), which is based on descriptive

metaphysics of Strawson and Parson’s roles. They

developed a “naïve notion” on ownership using as

basis the concepts permitted, forbidden, obligatory

and enabled extracted from (Hohfeld, 1913),

(Hohfeld, 1917) and (McCarty, 2002).

Ontology of Professional Judicial Knowledge

(OPJK) proposed by (Casellas, 2011) is based on

PROTON and other foundational ontologies, such

DOLCE. Although OPJK is introduced as “a legal

ontology developed to map questions of junior

judges to a set of stored frequently asked questions”,

there are generic legal concepts in OPJK that put this

ontology in the border between core and domain

ontologies.

Ontological Model of Legal Acts proposed by

(Gostojic and Milosavljevic, 2013), is a formal

model of legal norms modeled in OWL. The purpose

of this ontology is to support the retrieval and

browsing of legislation. They represent legal

relations as a social relation regulated by legal norm

and relate rights and duties to this legal relation, but

omit other existing legal positions (e.g. permissions,

non-rights).

LOTED2 Core Ontology proposed by (Distinto

et al., 2014) is a legal ontology of European public

procurement notices, designed to support the

creation of Semantic Web Applications. It was built

by employing used concepts from LKIF-core

ontology schema and it was coded in OWL.

The systematic mapping of the literature on legal

core ontologies indicated the foundational and core

ontologies more used to base on legal ontologies as

shown Figure 3.

Figure 3: Use of foundational and core ontology in legal

ontologies (Griffo et al., 2015b).

Other works related with legal domain

representation cited in the literature, are: LEGOL,

the seminal work, by Stamper (Stamper, 1977),

NORMA (Stamper, 1991), Hafner’s semantic work

(Hafner, 1980), McCarty’s language for legal

discourse (LLD) (McCarty, 1989), Mommer’s

ontology (Mommers, 1999), Legal-RDF Ontology

(McClure, 2007), LegalRuleML-core ontology

(Athan et al., 2013), among others.

4 METHODOLOGY

The research will be primarily theoretical

(bibliographical and documentary research

methods), but also empirical (experiments).

The bibliographical method will be used to

develop the systematic mapping study, which will

map the state of the art on legal core ontologies. The

guidelines proposed by (Petersen et al., 2008) and

will be used for this method.

The documentary method is a systematic analysis

of relevant documents (primary sources) with

contents on the subject to be investigated

(Mogalakwe, 2006). It will allow the analysis of

laws, doctrines and jurisprudence in order to create a

consistent theoretical legal basis. In this context, the

representation of legal concepts, such as legal norm,

legal relation, legal position, will be elicit from these

sources. In addition, the experiments will evaluate

the results of this research by criteria of legal

correctness.

From the theoretical research, comparative

studies on the main legal core ontologies (CLO,

LRI-Core) will be produced to strengthen the

importance of building a legal core ontology with a

different legal perspective.

Regarding the method used for the development

of ontology, the method will be iterative and

incremental, starting with the representation of

fundamental legal relations concepts, and then the

study of other concepts, for instance, legal facts,

legal agents, legal norms, and legal objects from

documentary sources. Also, some methodologies

applied to ontology development have been studied,

for instance (Uschold and Gruninger, 1996),

(Uschold and King, 1995).

Regarding the empirical research method, the

purpose is to validate the hypothesis previously

outlined and verify the model by ontological criteria

of correctness, clarity, consistency, and coherence.

The experiments have the goals of, firstly, to

know if the UFO-L legal concepts can be used to

represent a legal domain, taking into account some

8

19

18

11

10

8

4

1

1

0 5 10 15 20

FOLAW

LRI-CORE

LKIF

DOLCE

CLO

PROTON + OPJK

FBO

SUMO

NM-CORE

DC3K 2015 - Doctoral Consortium on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

16

characteristics of modeling (rationality, facility,

clarity, consistency, coherence and completeness).

Secondly, to know if professionals in conceptual

modeling, working in legal institutions, can use the

UFO-L legal concepts to model legal domains and

how the conceptual modeling background can

influence the results. Finally, to know if legal

experts can interpret adequately the models built by

the beginners and professionals in conceptual

modeling using UFO-L legal concepts. The expected

result is that UFO-L be a bridge between

computational technical end users and law end users,

bringing expressivity, reusability and semantic

interoperability for legal domains.

The experiments are the following:

Experiment 1:

Participants: undergraduate students with previous

knowledge of UML and conceptual modeling.

Method: Legal scenarios will be provided to be

modeled using UML and, also, using concepts of

UFO-L. A form is presented at the end of the

experiment to check characteristics of the concepts

represented (e.g. clarity, consistency, completeness).

An additional individual form will be filled to point

out the difficulties and impressions faced by

participants.

Hypothesis 1. The use of concepts of UFO-L,

especially legal relators brings clarity and

completeness to the model built since legal relators

make explicit all existing elements in a legal

relation.

Hypothesis 2. The legal concepts in UFO-L can

improve the modeling ability of legal relations

because the reuse of existing concepts in a generic

level.

Experiment 2:

Participants: Professionals from Computer area with

experience in conceptual modeling of legal domains

and UML.

Method: The same legal scenarios provided in

the experiment 1 will be provided to be modeled

using UML and Concepts of UFO-L by these

participants. In addition, the same forms submitted

to Group 1 will be answer by participants in this

experiment.

Since the modeling background can bring some

bias to the experiment, the purpose of this

experiment is compare the results of the Experiment

1 with Experiment 2 to analyze the influence of the

modeling background.

Experiment 3:

Participants: Law experts (e.g. lawyers, judges, legal

analysts), decision makers to implement

technological solutions with or without experience

in conceptual modeling (e.g. coordinator of TIC

departments in Judicial Courts, Public Prosecutor’s

Offices, Attorney’s Offices).

Method: The experiment will have two phases.

In the first phase, legal concepts of UFO-L and a

form to verify some characteristics (e.g. correctness

and clarity) of these concepts will be presented. In

the second phase, a model built with UFO-L will be

provided to be interpreted by the participants. At the

end, a form will be provided to evaluate the

understanding of the participants (how clear and

easy to understand is UFO-L? How close the legal

concepts in UFO-L are to the real legal issues?). An

additional form will be answered by the participants

to point out the difficulties and the impressions each

participant had on existing legal concepts in UFO-L.

Hypothesis 3. The use of concepts of UFO-L,

especially legal relators, in legal domain modeling,

permits law end users to understand the model built

by ontologists and “speak” the same language used

by them.

Hypothesis 4. The legal concepts in UFO-L can

improve the modeling process, increasing the

understanding between law experts and computer

professionals.

5 EXPECTED OUTCOME

The main expected results are: 1) systematic

mapping study on legal core ontologies and

publication of results (Griffo et al, 2015b); 2)

Experiments conducted in several research groups

and legal institutions with the publication of results;

3) Legal core ontology (UFO-L) based on UFO with

the publication of results. A part of the taxonomy of

legal relations is shown in Figure 4; and 4) Defense

of the thesis and publication. The time line is shown

in Table 1 (year/semester).

UFO-L: A Core Ontology of Legal Concepts Built from a Legal Relations Perspective

17

Figure 4: fragment of legal relators taxonomy (Griffo et al., 2015b).

Table 1: Schedule of activities.

2015

1-2

2016

1

2016

2

2017

1

2017

2

Systematic

Mapping

x

Experiment 1

x

Experiment 2

x

Experiment 3

x

Modeling –

UFO-L

x x x x

V

alidation an

d

verification

x x x x

Defense of

Thesis

Proposal

x

Publishing

results

x x x x x

Defense of the

thesis

x

Publication of

the thesis

x

6 CURRENT STAGE OF THE

RESEARCH

The research concluded the systematic mapping

study and the results (universe, sample, sources,

research questions, exclusion and inclusion criteria,

process used, analysis of results, list of selected

papers, and biases) were published in Brazilian

Conference on Ontologies 2015 (Ontobras’15)

(Griffo et al., 2015a).

In addition, the first results of UFO-L (taxonomy

of legal relators, computer and legal theoretical

bases) were published in Workshop Multilingual on

Artificial Intelligence and Law held on Artificial

Intelligence and Law (MWAIL-ICAIL 2015) (Griffo

et al., 2015b). A recent model of UFO-L has been

developed and will be published next year.

The comparative analysis of existing legal core

ontologies (CLO, LRI-Core, UFO-L) is under

development, as well as a comparative analysis

between existing legal concepts in computational

approaches published in the literature and legal

concepts represented in UFO-L.

DC3K 2015 - Doctoral Consortium on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

18

REFERENCES

Alexy, R., 2010. A Theory of Constitutional Rights,

Oxford University Press.

Alexy, R., 2003. Constitutional Rights, Balancing, and

Rationality. Ratio Juris, 16(2), pp.131–140.

Athan, T. et al., 2013. OASIS LegalRuleML. In ICAIL

’13. ACM Press, p. 3.

Bench-Capon, T., Araszkiewicz, M., Ashley, K.,

Atkinson, K., Bex, F., Borges, F., Wyner, A.Z., 2012.

A history of AI and Law in 50 papers: 25 years of the

international conference on AI and Law. Artificial

Intelligence and Law, 20(3), pp.215–319.

Breuker, J. & Hoekstra, R., 2004. Epistemology and

ontology in core ontologies: FOLaw and LRI-Core,

two core ontologies for law. In Proceedings of the

EKAW*04 Workshop on Core Ontologies in Ontology

Engineering.

Breuker, J., Muntjewerff, A. & Bredewej, B., 1999.

Ontological modelling for design educational systems.

In Proceedings of the AI-ED 99 Workshop on

Ontologies for Educational Systems.

Caralt, N. C., 2008. Modelling Legal Knowledge through

Ontologies. OPJK: the Ontology of Professional

Judicial Knowledge. Universitat Autònoma de

Barcelona.

Casanovas, P., 2012. A Note on Validity in Law and

Regulatory Systems. Quaderns de filosofia i ciència,

42(2011), pp.29–40.

Casellas, N. U., 2011. Legal Ontology Engineering.

Ceci, M., 2013. Interpreting Judgements Using

Knowledge Representation Methods And

Computational Models of Argument. Alma Mater

Studiorum, Università di Bologna.

Distinto, I., D’Aquin, M. & Motta, E., 2014. LOTED2 : an

Ontology of European Public Procurement Notices. In

Semant. Web Interoper. Usability Appl.

Gangemi, A., 2007. Design patterns for legal ontology

construction. In LOAIT. pp. 65–85.

Gordon, T. F., 2005. Artificial Intelligence and Legal

Theory at Law Schools. Artificial Intelligence and

Legal Education, pp.53–58.

Gostojic, S. & Milosavljevic, B., 2013. Ontological Model

of Legal Norms for Creating and Using Legal Acts.

The IPSI BgD Transactions on Internet Research,

9(1), pp.19–25.

Griffo, C., Almeida, J. P. A. & Guizzardi, G., 2015a. A

Systematic Mapping of the Literature on Legal Core

Ontologies. In Brazilian Conference on Ontologies,

Ontobras.

Griffo, C., Almeida, J. P. A. & Guizzardi, G., 2015b.

Towards a Legal Core Ontology based on Alexy ’ s

Theory of Fundamental Rights. In Multilingual

Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Law, ICAIL

2015.

Gruber, T., 1995. Toward principles for the design of

ontologies used for knowledge sharing. International

Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 43(5-6),

pp.907–928.

Guarino, N., 1998. Formal Ontology in Information

Systems. In

Formal Ontology in Information Systems

(FOIS). Trento, Italy: IOS Press, pp. 3–15.

Guarino, N. & Guizzardi, G., 2015. “ We need to discuss

the Relationship ”: Revisiting Relationships as

Modeling Constructs. In 27th International

Conference, CAiSE 2015 Proceedings. Sweden:

Springer International Publishing, pp. 279–294.

Guizzardi, G., 2005. Ontological Foundations for

Structural Conceptual Model, Veenendaal, The

Netherlands: Universal Press.

Guizzardi, G., Falbo, R. & Guizzardi, R.S.S., 2008.

Grounding Software Domain Ontologies in the

Unified Foundational Ontology ( UFO ): The case of

the ODE Software Process Ontology. In CIbSE. pp.

127–140.

Hafner, C. D., 1980. Representation of knowledge in a

legal information retrieval system. In Proceedings of

the 3rd annual ACM conference on Research and

development in information retrieval. pp. 139–153.

Hage, J. & Verheij, B., 1999. The law as a dynamic

interconnected system of states of affairs : a legal top

ontology -. Int. J. Human-Computer Studies, 51,

pp.1043–1077.

Hoekstra, R. et al., 2009. LKIF core: Principled ontology

development for the legal domain. In Frontiers in

Artificial Intelligence and Applications. pp. 21–52.

Hoekstra, R. et al., 2007. The LKIF core ontology of basic

legal concepts. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings. pp.

43–63.

Hohfeld, W. N., 1917. Fundamental Legal Conceptions as

Applied in Judicial Reasoning. Faculty Scholarship

Series, Paper 4378.

Hohfeld, W. N., 1913. Some Fundamental Legal

Conceptions. The Yale Law Journal, 23(1), pp.16–59.

Isotani, S. and Bittencourt, I.I. Dados Abertos Conectados.

Ed. Novatec.

Kececi, N. & Abran, A., 2001. An integrated measure for

functional requirements correctness. IWSM2001, 11th.

Kitchenham, B. & Charters, S., 2007. Guidelines for

performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software

Engineering. Engineering, 2, p.1051.

Kralingen, R. Van, 1997. A Conceptual Frame-based

Ontology for the Law. In Proceedings of the First

International Workshop on Legal Ontologies. pp. 6–

17.

Kuhn, W., Kauppinen, T. & Janowicz, K., 2014. Linked

Data - A Paradigm Shift for Geographic Information

Science. Springer Lecture Notes in Computer Science,

8728, pp.173–186.

Masolo, C., Borgo, S., Gangemi, A., Guarino, N.,

Oltramari, A., 2003. IST Project 2001-33052

WonderWeb Deliverable D18. Ontology Infrastructure

for the Semantic Web,

McCarty, L. T., 1989. A language for legal Discourse I.

basic features. In Proceedings of the 2nd international

conference on Artificial intelligence and law

.

McCarty, L. T., 2002. Ownership: A case study in the

representation of legal concepts. Artificial Intelligence

and Law, 10(1-3), pp.135–161.

UFO-L: A Core Ontology of Legal Concepts Built from a Legal Relations Perspective

19

McClure, J., 2007. The legal-RDF ontology. A generic

model for legal documents. In LOAIT 2007 Workshop

Proceedings. pp. 25–42.

Mogalakwe, M., 2006. The Use of Documentary Research

Methods. African Sociological Review, (1), pp.221–

230.

Mommers, L., 1999. Knowing the law. Legal Information

Systems as a Source of Knowledge Kluwer, ed.,

Nardi, J.C. et al., 2013. Towards a commitment-based

reference ontology for services. Proceedings - IEEE

International Enterprise Distributed Object

Computing Workshop, EDOC, pp.175–184.

Oberle, D., 2006. Semantic Management of Middleware,

Vol. 1. Springer Science & Business Media.

Petersen, K. et al., 2008. Systematic mapping studies in

software engineering. EASE’08 Proceedings of the

12th international conference on Evaluation and

Assessment in Software Engineering, pp.68–77.

Schneider, L. N., 2001. Naive Metaphysics, London.

Shaheed, Jaspreet, Alexander Yip, and J. C., 2005. A Top-

Level Language-Biased Legal Ontology. In ICAIL

Workshop on Legal Ontologies and Artificial

Intelligence Techniques (LOAIT).

Staab, S. et al., 2001. Knowledge processes and

ontologies. IEEE Intelligent Systems and Their

Applications, 16(1), pp.26–34.

Stamper, R. K., 1977. The LEGOL 1 prototype system and

language. The Computer Journal, 20(2), pp.102–108.

Stamper, R. K., 1991. The Role of Semantics in Legal

Expert Systems and Legal Reasoning. Ratio Juris,

4(2), pp. 219–244.

Uschold, M. & Gruninger, M., 1996. Ontologies:

Principles, methods and applications. Knowledge

Engineering Review, 11, pp.93–136.

Uschold, M. & King, M., 1995. Towards a methodology

for buiding ontologies. IJCAI-95 Wokshop on Basic

Ontological Issues in KNowledge Sharing.

Valente, A., 1995. Legal Knowledge Engineering; A

Modelling Approach, Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Valente, A. & Breuker, J., 1994. Ontologies: the Missing

Link Between Legal Theory and AI & Law. In Legal

knowledge based systems JURIX 94: The Foundation

for Legal Knowledge Systems. pp. 138–149.

Valente, A. & Breuker, J., 1996. Towards Principled Core

Ontologies. In Proceedings of the Tenth Workshop on

Knowledge Acquisition for Knowledge-Based Systems.

DC3K 2015 - Doctoral Consortium on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

20