Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain

A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research

Federico Cabitza and Angela Locoro

Dipartimento di Informatica, Sistemistica e Comunicazione,

Universit

`

a degli Studi di Milano Bicocca, Viale Sarca, 336, 20126, Milano, Italy

Keywords:

Knowledge Artifact, Situativity, Objectivity, Natural Language Processing, Polarity Detection.

Abstract:

In this paper, we present a method by which to build a metaphorical map of a portion of the scholarly literature

along conceptual dimensions that have been previously characterized in terms of positive, negative and neutral

terms. The method allows to “locate” scholarly works in this space, according to multiple criteria, like the

definitions that they contain; the relevant concepts that can be extracted by means of a content analysis; and

relevant passages that researchers can extract in studying their content. The resulting maps are not representa-

tional, nor trying to extract any objective essence of a scientific contribution. Rather, they are resources for the

qualitative research, review and interpretation of literature sources. As such, these maps are “knowledge arti-

facts” in themselves, as they visualize, so to say, the interpretation of a set of works by qualitative researchers,

and allow to build a visual comprehension of topological and qualitative relationships between the considered

literature contributions. We applied the method to the case of the “knowledge artifact” literature and report

the main results in this paper.

1 INTRODUCTION

A Knowledge Artifact (KA) is any artifact built to

support knowledge-related processes. This purposely

generic definition allows to cover a broad spectrum of

instances of this concept, which nevertheless present

many differences and mirror different perspectives to-

ward what knowledge is and how it can be supported.

In a recent qualitative literature survey (Cabitza

and Locoro, 2014), the authors accomplished an ex-

tensive review of the heterogeneous scholarly contri-

butions that had focused that far on the concept of

Knowledge Artifact. This review resulted in an inter-

pretative and bottom-up framework by which to char-

acterize single instances of a KA in terms of two op-

posite and complementary design dimensions: objec-

tivity and situativity. In that work objectivity was de-

noted as the dimension characterizing the KAs that

are more oriented to a model-driven and Artificial In-

telligence (AI) approach to knowledge management.

Conversely, situativity was considered the dimension

characterizing those KAs that adopt a more construc-

tivist, practice- and collaboration-oriented approach

to knowledge support. It is obvious that clear-cut dis-

tinctions are useful only for theoretical and analyti-

cal purposes, and that in reality both dimensions are

present at different degrees in each Knowledge IT Ar-

tifact (KITA). The above-mentioned literature review

was aimed at discovering this two-dimensional mix

by a qualitative analysis that was carried out by the

researchers manually.

An ideal continuation of this approach may be the

application of a more systematic method by which to

extract a sort of polarity of the literature sources un-

der consideration along some dimensions of interest,

like the two mentioned above; and then to represent

these sources in the metaphorical space defined by

these conceptual dimensions, which are assumed to

be orthogonal and independent.

Thus this paper can be seen as a follow-up of the

contribution mentioned above in that: 1) it proposes

a method by which to build a knowledge artifact sup-

porting the study of a body of scholarly contributions;

and 2) also, by applying this method in a case study

focusing on the KA literature, it sheds light on the

more recent and relevant contributions from this body

of literature.

The method by which the conceptual space men-

tioned above would be populated is based on the con-

tent that the researchers extract from the literature

sources during their analysis, and takes also in con-

sideration specific lexicons (i.e., lists of words) that

444

Cabitza, F. and Locoro, A..

Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain - A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2015) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 444-451

ISBN: 978-989-758-158-8

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Table 1: The objectivity (above) and situativity (below) lexicons.

algorithm, analytical, artifact, autonomous, autonomy, bi, body, business, capture, categorize, codification, codify, com-

bination, communicate, communication, complete, computational, concept, conceptual, correct, crm, datawarehouse,

decidable, decision, determinist, deterministic, discrete, document, dss, encode, engineer, engineering, exchangeable,

expert, explicit, externalization, externalize, externalizing, factual, fix, formal, formalism, formality, functionalist, hard-

coded, hard-code, independent, independently, information, intelligence, is, ka, km, knowledge, management, map,

metadata, minimalistic, minimalist, model, nomothetic, objective, objectivist, objectivistic, objectivity, olap, ontol-

ogy, order, outcome, passive, positivist, positivistic, predictive, prescribe, prescriptive, problem, procedural, procedure,

process, processual, procedural, rational, record, regulation, repository, represent, representable, representation, repre-

sentational, retrieve, semantic, semi-formal, solve, specify, static, store, structure, symbolic, top-down, transfer, valid,

validity, validate.

action, actionable, activity, affordance, agency, articulate, articulation, artifact, augment, awareness, beyond, body,

bottom-up, brainstorming, cad, chaotic, co-worker, co-create, co-creation, collaborate, collaboration, collectivity, col-

lectively, communicate, communication, community, constructivism, constructivist, constructivistic, consumer, con-

text, contextual, continuous, convey, cooperate, cooperation, cop, creative, cultural, cybernetic, decision, document,

emerge, emergentist, enable, evolve, experience, externalize, embody, fit, flexibility, flexible, fluid, groupware, holistic,

human-embodied, human-embody, incomplete, informal, information, innovation, input, integrate, interact, interac-

tion, interative, intermediary, internalization, interpretation, interpretive, interpretable, ka, knowledge, learn, learner,

learning, local, locality, malleability, malleable, manipulate, mediate, mediation, negotiable, nominalism, nominal-

ist, nominalistic, organization, others, partial, perform, performance, personalization, practice, pragmatic, pragmatist,

pragmatically, presence, problem, producer, product, proxy, reconcile, reconcilement, relational, result, retrieve, share,

situate, situation, situational, situativity, skill, social, socialization, sociotechnical, socio-technical, solve, stakeholder,

subjective, subjectivity, support, synergistic, tacit, team, think, thinking, training, transfer, undecidable, underspec-

ify, understand, understanding, unpredictive, unstructured, unstructure, usable, use, user-driven, utilization, vehicle,

voluntarist, voluntaristic, word, working.

the researchers have previously prepared for each di-

mension at hand (in our case, objectivity and situativ-

ity). These lexicons contain so called polar terms be-

cause their content is compared to the extracted con-

tent in order to measure the degree of polarity of a

paper with respect to each dimension, i.e., its degree

of dimension-ness.

As anticipated above, this space should be con-

sidered a knowledge artifact in itself for the follow-

ing reasons. Points in this space would not merely

“represent” literature sources, but rather help the re-

searcher look at, in a way, her reified interpretation

of those contributions, and be supported in getting a

visual comprehension of the literature of her inter-

est (in our specific case of the body of literature re-

garding the KA concept). The space and the objects

therein located would then support reflective insight,

collaborative discussion, and discovery, also, e.g., of

proximities, affinities, alignments, trends that can be

found among the analyzed sources (obviously still on

a metaphorical level). The maps that result from the

application of our method can then be seen as re-

sources for the qualitative interpretation of a body of

literature, as this latter is processed in terms of lin-

guistic prevalence and polarity. We will see how this

is accomplished in the next Section; then in Section 3,

we will validate the method by applying it to the KAs

research, and we will give some examples of how the

considered literature can be mapped giving visual evi-

dence of the intrinsic diversity of the scholarly contri-

butions and their possible interpretations. At last, we

will be back to the map metaphor again in Section 4,

which will close the paper.

2 METHOD

The method that we aim to propose for the visualiza-

tion of scientific content along the dimensions of ob-

jectivity and situativity

1

considers three intertwined

aspects that contribute in making a literature source

valuable: i) the definition aspect, represented in terms

of all of the sentences that in a paper give an ex-

plicit definition of a KA; ii) the design-oriented as-

pect, represented in terms of the sentences that in the

paper describe the functionalities or the main require-

ments motivating the design of a KA in the paper; iii)

the theoretical aspect, represented in terms of a list

of nominal categories that researcher can extract by

trying to understand the underlying assumptions that

drove the authors of a paper in discussing the defini-

tions as well as the design aspects of a KA. In par-

ticular, terms for describing the theoretical aspect can

result from any technique of content analysis and in-

terpretative paradigm aimed at the construction of a

theory, ontology or model, through the analysis of the

paper’s content, and can be seen as framework meta-

keywords that can be added to the paper through an

1

The reader should mind that the method is intended to

be general with respect to the dimensions of analysis, and

that we applied it to these two dimensions for the sake of

example only.

Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain - A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research

445

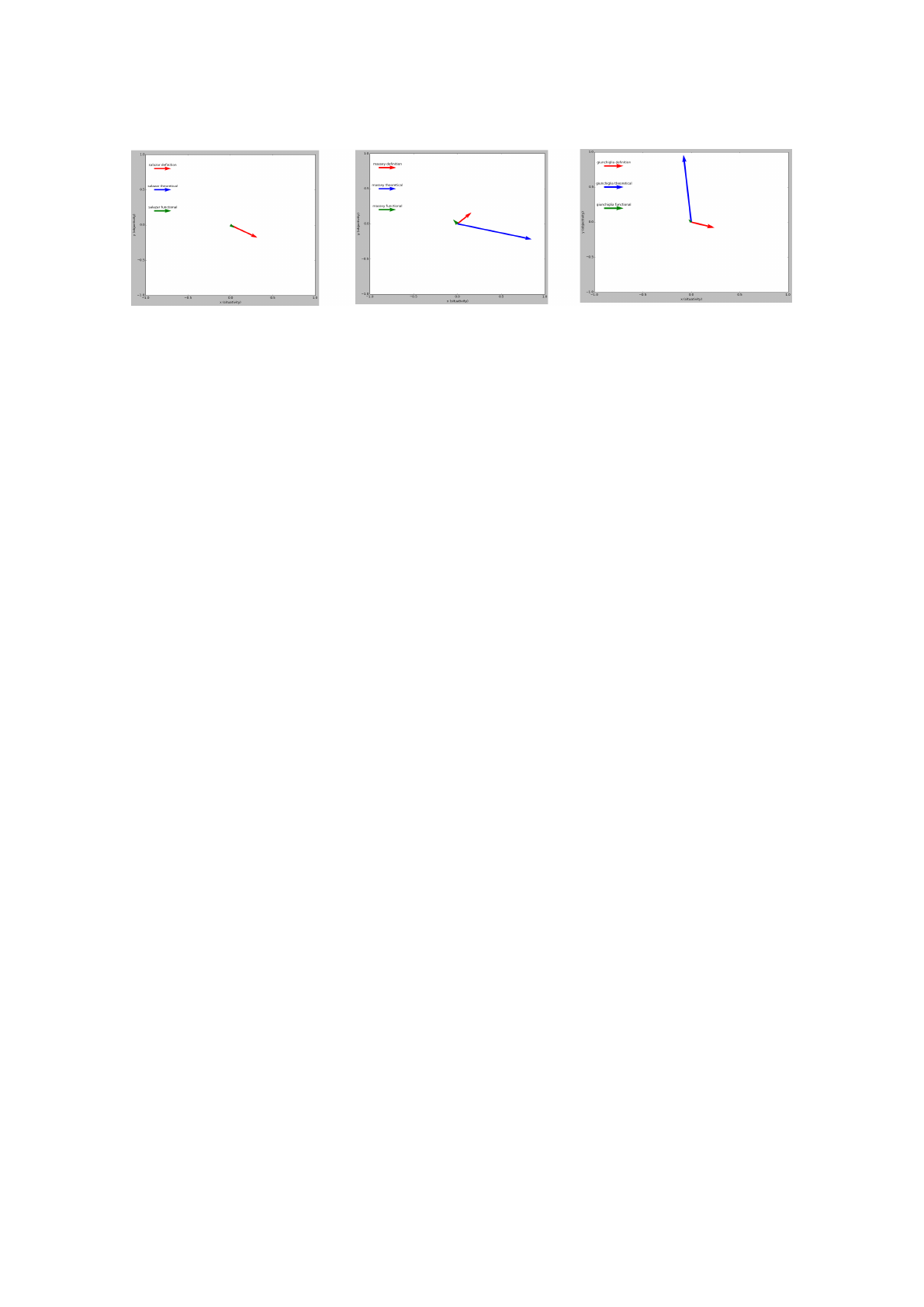

Figure 1: Visualization of the component vectors for, respectively, the definition, design, and theoretical aspects of the three

papers examined.

annotation process, to enrich it or support its interpre-

tation.

As anticipated in the Introduction, the method is

proposed as an interpretative tool, which could sup-

port expert scholars in getting a multimodal (i.e., both

textual and visual) comprehension of the conceptual

dimensions of the works they consider, flanking tradi-

tional techniques of content analysis that require both

reading and extracting meaningful material out of the

research papers under consideration.

Among the most popular applications of polar-

ity detection in written (and spoken) texts there are

“opinion mining” and “sentiment analysis” (Pang and

Lee, 2002). These approaches aim to “integrate

emotional aspects in natural language understand-

ing” (Cambria and Hussasin, 2015), in order to extract

information on the dimension of the “sentiment” of

people, that is their feeling or mood, being these vot-

ers, consumers, community-members or simply citi-

zens. For instance, the main approaches to sentiment

analysis are machine-learning and dictionary-based

ones (Rice and Zorn, 2013). The latter approach ex-

ploits a list of polar terms to give a measure of the

emotional valence of a text (either positive or nega-

tive), being it either a whole document, or a portion

of it, like just a single sentence.

In general, common techniques used to measure

a dimension of a text, like its “sentiment”, encom-

pass the representation of texts by means of word vec-

tors and word vector comparison by means of docu-

ment classifiers (Pang et al., 2002). However, “mining

opinions and sentiments from natural language [. . . ]

is an extremely difficult task as it involves a deep un-

derstanding of most of the explicit and implicit, regu-

lar and irregular, syntactical and semantic rules that

are proper of a language” (Cambria and Hussasin,

2015). Moreover, for long texts and generic vocab-

ularies “such approaches turns critically on the qual-

ity and comprehensiveness with which the dictionary

reflects the sentiment in the texts to which it is ap-

plied” (Rice and Zorn, 2013). For these reasons, a po-

larity detection approach would more probably result

suitable whenever applied to a specific domain, with

a specific domain vocabulary created by hand by do-

main experts, and applied to very short domain texts

or group of sentences. And as a means to further com-

prehension and interpretation of multiple texts, rather

than as an end in itself.

In this paper, we try to generalize the approach

of sentiment analysis to the analysis of any dimen-

sion that can be characterized by a vocabulary of

dimension-relevant (either positive or negative) terms

to extract and evaluate the polarity and valence (along

that dimension) of any text. In our specific case,

we are interested in potential expressions of objec-

tivity and situativity within a scientific KA-related

contribution, instead of positive or negative emotions

in generic content. We have applied the resulting

method to the case of the body literature regarding

both “representational KAs” and “socially-situated

KAs” (Cabitza and Locoro, 2014).

More precisely, in our method we represent strings

(i.e., sets of words, or 1-grams) in terms of vec-

tors along a dimension, that is elements in a mono-

dimensional vector space characterized by: a direc-

tion (i.e., a polarity, which we indicate as a coefficient

α); and a magnitude, i.e., the degree of dimension-

ness of the string; as said above, a common example

of dimension is “sentiment”, which can be either neg-

ative or positive, as well as situativity and objectivity,

as in the case study reported in Section 3.

We model the vector magnitude in terms of the

product of two components: β and γ. The former

is the valence of the predominat polarity within the

string with respect to the other polarity (within the

same string): therefore it is a sort of relative degree of

polarization of the string. The latter (γ) is the degree

of absolute polarity of the string, that is how much it

is polarized with respect to the total length. In other

words, we take the importance of the most relevant

lexicon within a text (γ), and then we weight it accord-

ing to its relative importance with respect to the other

lexicon within a specific string (β). Because the vec-

tor magnitude is normalized with respect to the string

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

446

length, string vectors are defined on a continuous in-

terval [-1, 1] symmetric around the origin (which rep-

resents perfect neutrality).

Obviously, strings can be represented along more

than one dimension (e.g. (Mikolov et al., 2013)). In

this case, they are vectors in a multidimensional vec-

tor space, that is sum vectors, resulting from the com-

position of each dimension vector defined above.

As anticipated in Section 1, to illustrate our

method we consider just two particular dimensions:

objectivity and situativity. For each of these two di-

mensions we defined one lexicon, D, divided in two

partitions, D

+

and D

−

: these are unordered sets of

both neutral and positive/negative words (1-grams,

excluding stop-words), respectively, with respect to

the dimension at hand. Furthermore, for simplic-

ity’s sake, in this study we assume that these two di-

mensions are mutual opposites, that is S

Situativity

+

≡

S

Ob jectivity

−

, and vice versa.

As hinted at in Section 1, our method also consid-

ers to extract three strings from each literature contri-

bution: the set of the definitions therein given by the

authors and identified as such by the researcher; the

set of codes that the researcher assigns to the paper,

following any hermeneutics technique; the set of the

relevant passages that the researcher extracts from the

paper. Each one of these strings are vectors in the bi-

dimensional vector space, or objectivity - situativity

plane.

Here we emphasize the main aim of the method

that is represented in the three Formulas 1, 2 and 3

to calculate polarity, valence and the string vector

magnitude, respectively. While a more syntactic ap-

proach would have been aimed at representing a re-

search contribution within the vector space by apply-

ing the method to the whole paper content, we aim

it at supporting qualitative research. Therefore, we

apply the algorithm represented in the formulas men-

tioned above to content that is produced by the qual-

itative researcher during the study of each literature

source. We then map the outputs of her study on the

definition, design and theoretical level in terms of a

cumulative vector (each vector associated with one

single paper) on the conceptual plane.

α =

(

−1 if

|

S

D

+

|

<

|

S

D

−

|

+1 if

|

S

D

+

|

≥

|

S

D

−

|

(1)

|

β

D

|

=

(

|

S

D

grt

|

−

|

(S

D

lwr

\(S

D

grt

∩S

D

lwr

))

|

|

S

D

+

∪S

D

−

|

if

|

S

D

+

|

6=

|

S

D

−

|

ε otherwise

(2)

γ

D

i

= β

D

i

·

|

S

D

grt

|

|

S

|

(3)

In Formula 1, α is the polarity coefficient; it is +1

if D

grt

is D

+

(the positive lexicon defined for dimen-

sion D), that is when the cardinality of D

+

is greater

than the cardinality of D

−

(the negative lexicon de-

fined for dimension D ); α is -1, otherwise, that is if

D

grt

is D

−

or the cardinality of D

−

is greater than the

cardinality of D

+

.

In Formula 2, S

D

+

is the set of occurrences of

the words belonging to D

+

, that has been found in

the string S (also, the set of word occurrences con-

noted either positively or neutrally along dimension D

within S). S

D

−

is the set of occurrences of the words

belonging to D

−

that has been found in the string

S (also, the set of word occurrences connoted either

negatively or neutrally along dimension D within S).

S

D

grt

and S

D

lwr

indicate which set among the two sets

mentioned above has greater and lower cardinality, re-

spectively, with respect to the other set. The ε param-

eter is an arbitrarily small constant (e.g., .1) to allow

for the visualization of null polarity. In our method,

if we detect a prevalence of either positive or nega-

tive words within the string S, we connote the neu-

tral words, that are the words contained in D

+

∩ D

−

,

as either positive or negative, respectively. This sim-

ple context-based and majority-driven polarization of

neutral words is reasonable when the difference be-

tween the cardinality of S

D

+

and S

D

−

is much greater

than the number of neutral words defined in both lex-

icons, as it is often the case.

In Formula 3, γ

D

i

is the magnitude of the string

vector, that is the coordinate associated with valence

β

D

i

taken along the axis representing the i-th dimen-

sion. In calculating the cardinality of S, duplicate

words are considered as many times they are repli-

cated.

3 THE CASE STUDY

The method described in Section 2 was applied to the

case of the “knowledge artifact” literature, in order to

validate it and report the outcome of its application

to a typical qualitative research task: literature review

and study.

To this aim, we created the objectivity and sit-

uativity lexicons by hand; as anticipated above,

these lexicons encompassed positively related terms,

negatively-related ones in two distinct partitions, and

neutral words in both of them, i.e. words that can-

not be considered as either clearly positive or nega-

tive, but that nevertheless are relevant for the domain

at hand (e.g., “knowledge”). We then applied our

method of polarity detection to a selection of research

papers identified in (Cabitza and Locoro, 2014).

Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain - A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research

447

Figure 2: Mapping of the considered papers in regard to their definition aspect within the objectivity-situativity plane.

To create the lexicons we proceeded as follows.

We considered 22 papers that in (Cabitza and Locoro,

2014) were found to contain one or more explicit def-

inition statements of the KA, and 3 more research pa-

pers from the 10 papers that in that literature survey

were found to be concerned with KA design. These

latter works are (Massey and Montoya-Weiss, 2006;

Salazar-Torres et al., 2008; Giunchiglia and Chenu-

Abente, 2009). The authors extracted the terms from

these primary sources independently, on the basis of

their perceived relevance and capability to connote

the concepts of objectivity and situativity (either pos-

itively or negatively).

The overall list of terms contained all of the terms

extracted by both of us, while terms extracted by only

one of the authors were reviewed jointly to decide for

its inclusion on the list. Then we classified the identi-

fied terms as either positive or negative (and of course

neutral), also in this case independently: inter-rater

agreement was assessed in terms of Cohen’s kappa,

and this process iterated each time after a short dis-

cussion on the term that had been classified differ-

ently. After a few iterations, we got sufficient agree-

ment for both the objectivity and situativity lexicons,

which are reported in Table 1. So far objectivity terms

are 103, whereas the situativity lexicon contains 145

terms. We recall here that, as part of our method, the

lexicons can be continuously refined, for any further

research purpose, also according to the papers consid-

ered and the raters involved.

The 22 papers mentioned above were used also

to validate our procedure of polarity detection and

visual mapping. In particular, we extracted the KA

definitions as bag-of-words, and processed them as

1-grams by means of a Python script that executed

the lemmatization of word tokens

2

and the removal

of stopwords

3

. We then computed the valence men-

tioned in Section 2 according to Formulas 2 and 1,

and computed the objectivity as well as the situativity

degrees by exploiting Formula 3.

Figure 2 depicts the visual mapping of the 22 pa-

pers according to their definitions of KA in terms of

situativity and objectivity coordinates, which result

from the application of our method

4

.

An example of insight that this kind of visualiza-

tion can suggest is how the literature has changed over

time: from Figure 2, by looking at the paper position

and their date of publication (marked in the point la-

2

We used the Wordnet lemmatizer of the nltk package

available at http://www.nltk.org/index.html

3

The stopwords list is availabe

at http://algs4.cs.princeton.edu/35applications/stopwords.txt

4

In Figure 2 we chose to plot only the resulting points,

and not the entire vector, for readability’s sake.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

448

bel) one can observe that, in recent times, the number

of situativity-oriented works is increasing over time

(showing perhaps a growing interest or sensitivity to-

wards that approach?). Another example is the ob-

servation of the formation of “clusters” of papers in

particular areas of the space (e.g. the I, the II and

the IV quadrants), and with particular distance pro-

portions and shapes: e.g. the uniformity of spacing

between the papers located in the II quadrant; the mu-

tual proximity of the papers of the I quadrant; the

more scattered set of papers of the IV quadrant. This

can give some hints on the linguistic uniformity in the

definitions of the “representational” (hence more ob-

jective) KAs and, on the contrary, of the linguistic

variety in the definitions provided for the “socially-

situated” KAs. Also, a further look can be given

to see whether close papers are also describing sim-

ilar KAs, or whether the same researcher (or group

of researchers) has maintained the same theoretical

“stances” over time, and so on.

In general, with this kind of qualitative visualiza-

tion it is possible to inquire into the linguistic prop-

erties of the papers that the method has grouped to-

gether (spatially) to see whether they should be also

grouped conceptually to some extent (e.g., by writing

style, by theoretical stance, by objectivity and situa-

tivity attitude, and so on). As the researchers’ aims

can vary a lot, as well as their “mental models”, dif-

ferent “mappings” can be open to various interpreta-

tion and insights, according to the research scope and

aims that tap in this particular knowledge artifact.

For the 3 papers that focused on three specific KA

applications, we proceeded as follows. We created

three word sets, obtained by extracting: their defi-

nitions (as in the 22 papers mentioned above); the

relevant passages describing the concrete application

of the KA at hand; the keywords that the authors

agreed to apply to each of them. For this latter task,

we followed a hybrid approach (Fereday and Muir-

Cochrane, 2008), trying to apply the lexicon terms

first, but then also any other code we agreed upon,

after a short cycle of iterative revisions.

Applying the script mentioned above to these

three word sets, we obtained the component vectors

related, respectively, to the definition-, the theory-

and design-related aspects of each paper (see Fig-

ure 1 for a representation of each dimension as a

vector for each paper). This representation allows

to compare each of the relevant dimensions of a pa-

per, and to compare them with the same dimensions

of other papers, discovering for example that the pa-

per (Salazar-Torres et al., 2008) has a uniform di-

rection of the three dimensions of definition, the-

ory and design, whereas the paper (Giunchiglia and

Chenu-Abente, 2009) presents quite an opposite view

in terms of definitiorial vs theoretical stances; fi-

nally, the paper (Massey and Montoya-Weiss, 2006)

lays “somewhere in the middle”, presenting with a

more emphasized socially-situated stance along the

theoretical dimension with respect to the definito-

rial dimension. The design-related aspects of both

the papers (Giunchiglia and Chenu-Abente, 2009)

and (Massey and Montoya-Weiss, 2006) seem to go

in the opposite directions along the theoretical dimen-

sion, although the design aspect seems to be less tech-

nical in the latter work than in the former one, which

covers the technical details of the knowledge artifact

at hand for approximately half of its length.

By composing together these three vectors for

each of the papers under consideration, we obtained

their overall vector representation on the objectivity-

situativity vector space, as depicted in Figure 3.

This figure shows that our content analysis was

such that paper (Salazar-Torres et al., 2008) looks less

situativity-oriented than paper (Massey and Montoya-

Weiss, 2006), and that paper (Giunchiglia and Chenu-

Abente, 2009) looks much more objectivity-oriented

than the first two papers

5

. Figure 2 can also suggest

considerations about the relative (conceptual) prox-

imity and mutual alignment between works: (Salazar-

Torres et al., 2008) is maybe closer to (Massey

and Montoya-Weiss, 2006) than to (Giunchiglia and

Chenu-Abente, 2009), but even more importantly,

they look more “aligned” to each other.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Terrain is not a territory. For the dictionary, a ter-

rain is any piece of ground with reference to its phys-

ical character. It is therefore the element of a terri-

tory that human beings have to cope with. We intend

this term metaphorically to intend the scholarly land-

scape encompassing the diverse literature contribu-

tions regarding any concept, and in our specific case

the concept of “knowledge artifact”. In this light, we

intend the term terrain used in the title to be seman-

tically closer to the French terroir, a term that tra-

ditionally “refers to the complex ecology in which a

given vineyard is located [and that] evokes the unique

5

We believe that trying to distinguish if the papers ac-

tually are or rather look according to the researcher inter-

pretative lens would be out of the scope of this work. The

maps provided by our method, like those depicted in Fig-

ures 3 and 2 are given as complementary visual resources to

content analysis and literature interpretation.

Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain - A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research

449

Figure 3: Visual mapping of the composite vectors for the three papers examined.

qualities of the soil, weather patterns, situated wine-

making practices, sunshine, and irrigation that yields

a particular and recognizable character to the wines

that result” (McNely and Rivers, 2014). If we take

the metaphor seriously, this means that the body of

literature contributions on a particular topic “exists

outside human control” (ibid.) but it also bears fruit

(like knowledge, insights, new ideas) only in the ac-

tual practice of the researchers that explore and, so to

say, harvest it.

Following the metaphor again: in order to exploit,

take possession of, and also orient themselves in, ter-

rains, human beings construct and use maps. One im-

portant point many cartography enthusiasts know well

is that maps do not necessarily depict or represent

(figuratively) terrains; obviously maps relate to ter-

rains, but they are rather “resources for action” (Such-

man, 2007), that is means to understand, explore and

exploit terrains. A typical practice where maps are

used is wayfinding: in this case, maps are just like

marked pathways in the wood, or signposts affixed at

relevant crossroads. Another practice is also contem-

plation: maps can be consulted just for the aesthetic

pleasure to find them accurate, complete, up-to-date,

clean and elegant. This should not be considered a

lazy activity, as maps can also act as triggers for de-

tecting relationships between terrain elements, as well

as to reflect on them and discuss them.

In this paper we have presented a way to map a

metaphorical terrain of a portion of the scholarly lit-

erature found to be related to a specific topic. This

terrain unfolds conceptually along discursive dimen-

sions, that is dimensions that are characterized in

terms of positive, negative and neutral terms. The

mapping method we devised, although simple, allows

for a cursory “locating” of scholarly works in this

space according to multiple criteria, like the defini-

tions that they contain; the relevant concepts that can

be extracted by means of a content analysis; and rele-

vant passages that researchers can extract in studying

their content. Some of the insights that researchers

may pull out from the visual representations given in

all of the Figures of this paper have been illustrated

in Section 3 as an outcome of our analysis and clas-

sification of the papers. Once again, we stress the

fact that the task of placing single contributions in the

terrain of interest (that is a discursive terrain) should

then not be taken as a task of representation of each

source’s position (even supposing such a thing really

exists or can be pinpointed in any metaphorical space)

within this landscape. Indeed, our method is highly

dependent on qualitative content analysis in regard to

all of its inputs: both the dimensional lexicons, and

the strings (set of words) representing each literature

source.

The resulting maps that our quantitative method

allows to build are not aimed (nor built) to represent

a body of works, nor to extract any objective essence

of a scientific contribution, if such a thing exists. Far

from it, those maps are intended as resources for the

interpretation of selected papers by the qualitative re-

searcher, as an aid to literature reviews to allow for

qualitative comparisons and evaluations, and a trig-

ger for discussion and idea exchange between schol-

ars about what they study.

That is why we claim that these maps are “knowl-

edge artifacts” in themselves; indeed, they visual-

ize, so to say, the interpretation of a set of works by

qualitative researchers, and allow them to build a vi-

sual comprehension of topological and qualitative re-

lationships between the considered literature contri-

butions.

In particular, we applied the method to the case of

the “knowledge artifact” literature. As such the paper

contributes in the literature regarding the concept of

knowledge artifact in regard to two main aspects.

KITA 2015 - 1st International Workshop on the design, development and use of Knowledge IT Artifacts in professional communities and

aggregations

450

• First, we have defined pairs of lexicons (positive

and negative ones) for the dimensions of situa-

tivity and objectivity (of knowledge artifacts), as

these had been defined in (Cabitza and Locoro,

2014). These lexicons have been both produced

and reconciled manually, after a comprehensive

review of a set of relevant papers and an itera-

tive process of inter-rater agreement that involved

the authors. These vocabularies are offered to the

community of interested researchers to be pro-

gressively maintained, and to enable further re-

search on these topics along the same research

strand advocated in (Cabitza and Locoro, 2014).

• Then, we propose an algorithm for the mapping

and visualization of arbitrary sets of words (either

directly taken or derived from the original liter-

ature sources) into the objectivity-situativity bi-

dimensional vector space. In this paper, to val-

idate the method we produced the resulting out-

puts:

1. the set of the main definitions of knowl-

edge artifact explicitly given by the authors of

22 papers selected from the review presented

in (Cabitza and Locoro, 2014);

2. the sets of definitions and relevant categories

that we extracted from three relevant papers

selected from the literature review mentioned

above;

3. the sets of all of the relevant design-oriented

passages that we extracted from each of these

papers, having in mind the concrete applica-

tions mentioned in each contribution.

• Each paper has then be mapped in terms

of a graphical representation within a vector

space, by considering its definition-, theory-

and application-oriented aspects (respectively, the

word sets of its definitions, categories and rel-

evant passages). The vector-like representation

should be also appraised for the related affordance

of a “tension” and for evoking a “tendency” rather

than a mere position, which eludes any too rigid

pinpointing of the characteristics of a research

contribution.

If the interpretation of a set of literature sources

and the discussion of the related topics can be fos-

tered by looking at the vector space that we propose

to build with our method as a map for qualitative lit-

erature reviews, the main goals of our study would

be reached. In this case, our method could comple-

ment the study of scholarly sources, and facilitate the

qualitative researcher in extracting insights from the

literature.

REFERENCES

Cabitza, F., Locoro, A. (2014). ”Made with Knowledge” -

Disentangling the IT Knowledge Artifact by a Qual-

itative Literature Review. In Procs of KMIS 2014.,

64–75.

Cambria, E., Hussein, A. (2015). Sentic Computing: A

Common-Sense-Based Framework for Concept-Level

Sentiment Analysis Springer.

Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2008). Demonstrating

rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach

of inductive and deductive coding and theme devel-

opment. International journal of qualitative methods,

5(1), 80-92.

Giunchiglia, F. & Chenu-Abente, R. (2009). Scientific

Knowledge Objects v.1. Techreport DISI-09-006,

University of Trento.

Massey, A.P. & Montoya-Weiss, M.M. (2006). Unravel-

ing the temporal fabric of knowledge conversion: A

model of media selection and use. Mis Q, 30(1), 99–

114.

McNely, B. J., & Rivers, N. A. (2014, September). All of

the things: Engaging complex assemblages in com-

munication design. In Procs of the ACM International

Conference on The Design of Communication, p. 7.

Mikolov, T., Sutskever, I., Chen, K., Corrado, G. S., &

Dean, J. (2013). Distributed representations of words

and phrases and their compositionality. In Advances

in neural information processing systems (pp. 3111-

3119).

Pang, B., Lee, L. and Vaithyanathan, S. (2002). Thumbs

up?: sentiment classification using machine learning

techniques In Procs of the ACL-02 conference on

Empirical methods in natural language processing,

10:79–86.

Pang, B., Lee, L. (2008). Opinion mining and sentiment

analysis Foundations and trends in information re-

trieva, 2(1):1–135.

Turney, P.D. and Pantel, P. (2014). Corpus-based dictionar-

ies for sentiment analysis of specialized vocabularies

In Procs of NDATAD 2013.

Salazar-Torres, G. et al. (2008). Design issues for knowl-

edge artifacts. Knowledge-Based Systems, 21(8),

856-867.

Suchman, L. (2007). Human-machine reconfigurations:

Plans and situated actions. Cambridge University

Press.

Turney, P.D. and Pantel, P. (2014). From frequency to mean-

ing: Vector space models of semantics. J Artif Intell

Res, 141–188.

Mapping the Knowledge Artifact Terrain - A Quantitative Resource for Qualitative Research

451