Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

Boris Fritscher

1

and Yves Pigneur

2

1

HEG-Arc, HES-SO // University of Applied Sciences Western Switzerland, 2000 Neuchâtel, Switzerland

2

Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

boris.fritscher@he-arc.ch, yves.pigneur@unil.ch

Keywords: Business Model Canvas; Computer-Aided Business Model Design; Guidelines.

Abstract: When designing and assessing a business model, a more visual and practical ontology and framework is

necessary. We show how an academic theory such as Business Model Ontology has evolved into the Business

Model Canvas (BMC) that is used by practitioners around the world today. We draw lessons from usage and

define three maturity level. We propose new concepts to help design the dynamic aspect of a business model.

On the first level, the BMC supports novice users as they elicit their models; it also helps novices to build

coherent models. On the second level, the BMC allows expert users to evaluate the interaction of business

model elements by outlining the key threads in the business models’ story. On the third level, master users

are empowered to create multiple versions of their business models, allowing them to evaluate alternatives

and retain the history of the business model’s evolution. These new concepts for the BMC which can be

supported by Computer-Aided Design tools provide a clearer picture of the business model as a strategic

planning tool and are the basis for further research.

1 INTRODUCTION

Competition for companies and start-ups has evolved

in the past decade. Today, success cannot be achieved

on product innovation alone. At a strategy level,

having the means to improve the design of business

models has become a real issue for entrepreneurs and

executives alike. Business models methods are a good

way to share a common language about part of a

strategy across a multidisciplinary team. These

methods enable quick communication, and help

improve the design of a new business model, as well

as assess existing ones.

There are many different business model

ontologies which focus, for example, on economics,

process, or value exchange between companies. One

such business model tool which is getting popular is

the Business Model Canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder &

Pigneur, 2010). Its visual representation and simple

common language are two essential characteristics

which have helped spread its adoption and make its

book a bestseller. The current version of the BMC is

an evolution from the original academic work the

Business Model Ontology (BMO) (Osterwalder,

2004). The need to evolve the model took place to

better fit the needs of practitioners over academics.

The visual representation was improved under the

influence of design thinking practice.

Through observation gained from, giving

workshops, teaching to students and a survey, it

appears that the building blocks of the BMC are

covering the main needs, however usage itself of the

model seems very basic and is limited to static

analysis of one business model at a given time. This

can be linked back to its original ontology which is

used to describe a static model.

In reality, companies have to change and adapt to

internal and external changes which impact their

business. Therefore, a business model method should

also consider the dynamic nature of transformation

and evolution of the model.

This brings us to the following research question:

How to represent and help to design the

dynamic aspect of a business model with the

Business Model Canvas?

Before answering the question we provide a

detailed history of the transformation of the BMC and

provide some lessons learned for business model

designers. Then in order to answer the question we

first contribute to a definition of the maturity level of

BMC users. Based on the three identified levels:

novice, experts and master, we split the main question

86

Fritscher B. and Pigneur Y.

Extending the Business Model Canvas - A Dynamic Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0005885800860095

In Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2015), pages 86-95

ISBN: 978-989-758-111-3

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

into three sub questions. For each, we contribute to a

concept on how to handle a particular dynamic aspect.

On the first level, the BMC supports novice users

as they elicit their models; it also helps novices to

build coherent models. On the second level, the BMC

allows expert users to evaluate the interaction of

business model elements by outlining the key threads

in the business models’ story. On the third level,

master users are empowered to create multiple

versions of their business models, allowing them to

evaluate alternatives and retain the history of the

business model’s evolution.

We adopted the following design science

structure for our paper: After this introduction, we

present the prior work on the business model canvas

with a focus on its origin, evolution and adoption.

Followed by a short presentation of the methodology

and how we address the research question in multiple

parts. The main artifact section presents two new

concepts: business model mechanics and business

model evolution, to help address designing the

dynamic aspect of a business model. In the evaluation

section we present the validity of the concept. We end

the paper with a discussion and a conclusion on the

implications for future research in business model

design.

2 PRIOR WORK

In this section we present the origin of the business

model canvas and how it evolved through the years

influenced by its adoption. Business model ontology

has evolved since its initial design. Retrospectively,

we can distinguish there distinct stages: 1) the

creation of Business Model Ontology (BMO), 2)

followed by its first confrontation with reality, 3)

which then paved the way for its design-influenced

redevelopment.

2.1 Business Model Languages

Whilst many other business model languages exist,

this paper does not include a detailed comparison of

them. We have, however, sought to highlight the

differences between Business Model Ontology

(BMO) and its closest alternatives. Starting around

the same time as BMO, e3-value (Gordijn &

Akkermans, 2001) includes many similar concepts,

many of which can be mapped between them

(Gordijn, Osterwalder, & Pigneur, 2005). In

particular, e3-value goes into more detail about the

interactions between the components. In addition, it

specifies the value which is exchanged in both

directions and the way in which it flows. Using e3-

value, it is possible to go beyond creating a single

business model; indeed, it is also possible to model

the interactions between business models within a

sector. This detailed modeling of interactions comes

with the necessity to specify ports through which the

connections flow. Consequently, this makes visual

representation more complex. The relationship

between elements can further be described with types

and values that allow for the basic financial

calculation of the model.

Whilst BMO is concerned with providing a small

but complete set of strategic components to describe

a business model, another modeling language, known

as SEAM (Wegmann, 2003) also exists. SEAM

focuses on enterprise architecture and addresses the

issue by providing a hierarchical decomposition. It

uses a visual representation to handle the

encapsulation of its hierarchies, which allows an

exploration of the underlying resources and processes

that contribute to the high level element. In the past

few years, SEAM (Golnam, Ritala, Viswanathan, &

Wegmann, 2012) and BMO (Osterwalder, 2012) have

both evolved ways to better describe and explore the

connection between the value proposition and

customer segments. An essential part of both models

is to be able to visually display the elements and show

their connections at the same level as the concepts.

The visual handling of encapsulation does, however,

generate complex diagrams, which can be hard to

read for the non-initiated.

Weill and Vitale (2001) illustrated a method for

the schematic description of e-business models. The

focus is on the simple interactions between the firm

and its customer and suppliers, which are drawn on a

blank canvas. An indication of the direction of

interactions is given, along with the type of flow.

Thus, it adds value to an interaction in a way that is

similar to e3-value; however, it is more general since

it does not define ports or go into more detail about

the flow itself.

2.2 2000-2004: Business Model

Ontology

The development of BMO emerged from the need to

define new business models for e-commerce around

the year 2000. Following academic research, a first

version of BMO was published in 2002 at the 15th

Bled Electronic Commerce Conference by

Osterwalder and Pigneur; it took the form of a

framework that was specially targeted at e-

businesses. Over the next two years, the work further

matured, resulting in the publication of Alexander

Osterwalder’s thesis (Osterwalder, 2004) in which he

described the key building blocks and their

interactions. The model was presented as an ontology

Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

87

with elements of the modeled case becoming

instances of the meta-level elements defined by the

ontology.

Business Model Ontology in its original version

uses nine building blocks to describe a business

model: Value Proposition, Customer, Channel,

Relationship, Revenue, Value Configuration,

Capability, Partnership, and Cost. The model’s scope

is limited to the business itself and does not directly

cover any environmental factors. Its key strength is

the emphasis it gives to the relationship between the

components. A coherent business model is created by

correctly connecting elements from within the nine

building blocks. Exploring these connections can help

to identify missing elements or discover ambiguous

assumptions within a model. In summary, BMO

focuses on identifying what is provided to whom,

how it is produced and how much profit it generates.

2.3 2004-2008: Use and Simplification

Following its academic publication (Osterwalder,

Pigneur, Tucci, 2005) the model was used in two

different contexts between 2004 and 2008. It was

applied to tutorial cases delivered to IS students; thus,

it was simplified, but still used in an academic

context. The model was also used with practitioners

in workshops and consulting sessions. Here, the

model was applied to actual business problems in

order to gain an understanding of how the model is

used within a wide spectrum of business types,

beyond just e-business models. Both of these

applications sought to constraint the model as a one-

page diagram. Special positioning was used to

identify the type of each element and best practice

was further strengthened by using keywords to

describe each element. The changes were not only

visual; the names of some of the elements themselves

were also changed to better fit the vocabulary of its

users. The nine names are: Value Proposition,

Customer Segment, Distribution Channel, Customer

Relationship, Revenue Stream, Key Resources, Key

Activities, Partner Networks, and Cost Structure.

2.4 2008-2012: Business Model Canvas

Insight gathered during the previous years and the

emergence of a small community around Alexander

Osterwalder’s blog led to the creation of a book

project to communicate the result of these

transformations. Convinced that the visual aspect of

the model is a key component and largely influenced

by the design-thinking movement and “managing as

designing” (Boland & Collopy, 2004), the book was

intended to offer a visual perspective. In turn, this led

to a designer being brought on board to redevelop the

layout of the canvas so that it became the Business

Model Canvas (BMC) we know today. New features

include the pictograms that illustrate the nine building

blocks from the theory, their rectangular layout and

an axis of symmetry around the value proposition

(left side, right side). By providing examples from

different industries, the book project further helped to

crystalize the ideas on the usage of the BMC. In

particular, it showed how the BMC can integrate a

design-thinking process and explored the notion of

partial meta business models known as patterns

(Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

To strengthen the link between theory and

practice, the book was written in collaboration with

the community. This was done by setting up a

community hub with forums. Early drafts were

published on the hub for review by subscribed

members. This created a following of those interested

in business model generation and further helped to

promote the book. Many followers also put business

model generation into practice, which eventually led

to its success. From the start, the community was

global in nature. Now, with many translations of the

book made available, it is expanding even further.

Teaching of the BMC has been adopted by

managerial and entrepreneurship courses in over 250

universities. In turn, this has increased adoption.

Furthermore, there has been a steadily increasing

number of workshops and consultant-led master

classes, as well as internal education programs in

large corporations.

Since the release of the book Business Model

Generation in 2010, adoption of the BMC has grown

to become a worldwide phenomenon: the original

community hub of 400 people which helped create

the book has grown to 14,000 members. The book

itself has been translated into 29 languages and sold

over 1,000,000 copies. Other communities, such as

Customer Development (Blank & Dorf, 2012), have

started using the BMC as a supporting model for their

theories.

3 METHODOLOGY

In this study, we used Design Science Research

(DSR), as described by (Gregor & Hevner, 2013).

They defined a process in which artifacts are built and

evaluated in an iterative process in order to solve the

relevant problems. The need to take a visual approach

to creating the BMC was driven by design-thinking

theories and we identified need for practitioners to

have better tools that can be easily integrated into

daily practice. Existing knowledge of business model

ontology has been described in the previous section.

It was shown that Information Systems (IS) has the

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

88

necessary body of knowledge to handle “strategizing

as designing” (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2013).

3.1 Users Maturity Level of Business

Model Canvas Modeling

The BM canvas was evaluated using data and

evidence from its use in the real world, books, canvas,

hub, and the workshops and lectures that were used to

inform the following three maturity levels inspired by

the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages (CEFR), which also has three groups.

Novice – use the BMC as a simple common

language and visualization help.

Expert – use the BMC as a holistic vision to

understand and target a business model’s

sustainability. They understand the model’s methods,

such as high level links and colors, which helps to

connect ideas and follow the interactions.

Master – use the BMC in the global Strategy,

which is a process that evolves and adapts to its

environment. They understand that the design of a

model has to accompany such a process by supporting

concepts of iteration, transformation (mutation) and

choosing alternatives (selection).

Having defined these three level of proficiency we

use it to decompose the research question into three

sub-questions:

Novice level usage is the most commonly

observed and fully applies to the static use of the

BMC. Before moving to a dynamic representation of

a business model, it should be guaranteed that at a

static level it is already a coherent model. Which

leads us to the following sub-question:

How can the static design usage of the business

model canvas be improved (in relation to its

coherence)?

Expert and Master level design of BMC are not

observed frequently and lack representation due to

their requiring a more dynamic aspect of the BMC.

For the expert with a focus on internal interactions

this leads us to the following sub-question:

How to represent the dynamic aspect of

interactions happening inside the business model?

Handling multiple states of a business model, due

to internal or external changes, at the master level

leads to the following sub-question:

How to represent the transformation from one

state to another of a business model?

In the next section, we address these questions

individually each with their own artifact.

4 ARTIFACT

In the next three subsection we consider each

business model canvas design task of each mastery

level by looking first at a metaphor of a similar design

task in another design domain. Transposing the

metaphor of house planning in architecture, plane

building in engineering and evolution in biology to

business model designing, we propose a concept to

help answer each sub question. Each level builds on

the previous and comes with their respective concept:

BM Canvas Coherence, BM Mechanics and BM

evolution, to address the dynamic nature of business

models. We then illustrate how each concept applies

to a small common example: the case of Apple’s iPod

business model. Each Artifact also describes in a

short summary the essence of the mastery level to

further offer a clear way to differentiate the three

levels.

The following three concepts are presented below:

BM Canvas Coherence helps the novice to

improve static business model modeling by way of

using guidelines to check coherence of the business

model.

BM Mechanics helps the expert by proposing to

use colors and arrows to outline the interactions

happening inside the business model.

BM Evolution helps the master by offering a way

to visualize business model transformation from one

state into another. Applying these transformation

multiple times results in a branch showing the

evolution of the business model.

A mapping between level and concept can be seen

in table 1.

4.1 BM Canvas Coherence

At the novice level, the focus is on the concepts of the

ontology, meaning the nine building blocks that

define a business model. The main task consists of

designing a business model by filling in elements for

each block. Designing a business model can be best

described using the metaphor of an architect engaged

in designing a house. The architect needs to know

about the various components of a house, such as the

walls, doors, windows, roof and stairs, and also how

they relate to each other. A wall can have windows

and doors. A room has four walls with at least one

door. Beyond such constraints, however, the architect

is free to produce a variety of designs for a house.

During the design process, the architect puts forwards

his ideas using sketches and prototype models. These

prototypes are not finished products, but are

specifically aimed at testing the interaction of a

selection of concepts in the specified context of the

Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

89

prototype. Transferring this design technique to a

business model design means creating different

business model variations of component interactions.

For example, when prototyping a specific customer

segment, the value proposition set could have its

revenue stream type switched from paying to free, or

from sales to subscription. This could then lead to

further prototype changes to dependent components.

This iterative validation of ideas leads to a business

model that has all its components matching to become

a “usable” business model. Checking the coherence

between the elements is a key requirement for a valid

business model. It is not enough to only produce a

checklist of items without verifying their

compatibility. Again, with reference to our

architecture metaphor, stairs should be used to

connect floors, and a door should lead to a room

rather than nowhere. We call this “usability”.

Similarly, in a business model, a value proposition

needs to offer added value to a customer segment

requiring it. A value proposition without a customer

segment indicates a non-coherent business model.

The iterative validation of design ideas can go as far

as “getting out of the building” and test the

assumptions directly with the potential customer as is

done in Customer Development (Blank & Dorf,

2012). The gained insights may help to validate the

hypothesis of the prototype or else offer new ideas to

make a pivot of the model to target different

customers.

In order to facilitate the checking of coherence,

there are a series of guidelines which we have

proposed to help validate the business model’s

elements and interaction (Fritscher & Pigneur 2014c).

They are split into three categories from element, to

building block and interactions:

Guidelines applying to individual elements for

example that the meaning of the element is

understandable by all stakeholders.

Guidelines applying to individual blocks for

example that the detail level of the elements are

adequate (there are not too many detailed elements,

nor too few which are too generic).

Guidelines applying to connections between

elements in different blocks for example that there are

no orphan elements: all elements are connected to

another element (in a different block to themselves).

4.1.1 In Summary

At the novice level, the concepts of the model identify

the right elements and how they are related to one

another. An iterative process that explores detailed

features of the elements helps to adjust the elements

that make up the model in order to solve real

problems. This leads to a coherent model that

addresses the right job.

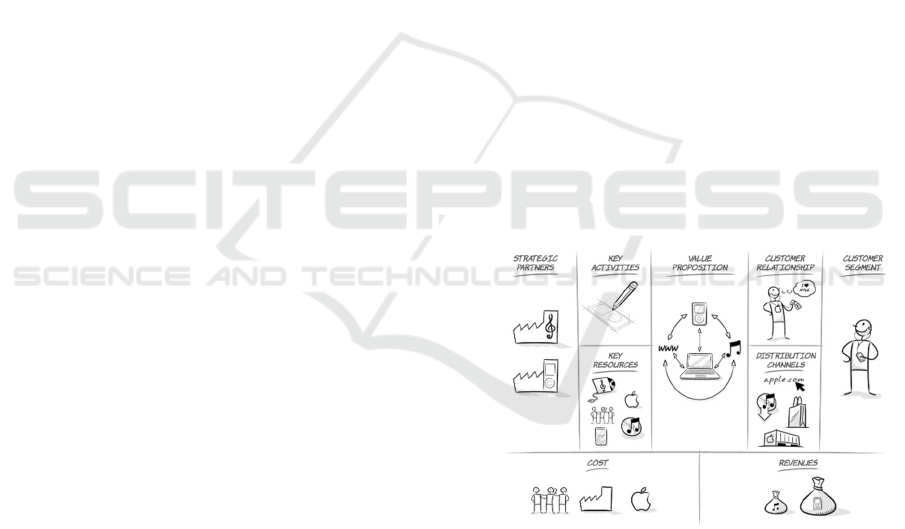

4.1.2 Apple iPod BM Canvas

In this example, we focus on Apple’s iPod business

model. A model can be described by its elements,

with keywords for each of the nine building blocks.

Alternatively, illustrations can be used, as shown in

Figure 1. The value proposition is a seamless

experience that includes listening, managing and

buying music. It is targeted at consumers who want to

listen to music wherever they go and have access to a

computer. The distribution channels to reach these

consumers is a store or online-shop where the device

can be bought along with iTunes software to manage

the music library. Sales of the device generate

revenue with higher margins than sales of the songs,

where most of it goes to the majors. The customer

relationship is oriented towards the lifestyle

experience of Apple products. In order to offer these

services, the key activity is the design of the device.

Key resources are the device itself, music contracts,

the developers and the Apple brand which strengthens

the customer relationship. Marketing and developers

are the key cost structures. Music licensing and

device manufacturing is carried out through the

partners.

This business model slice is coherent since as

described each element is connected to another. There

are no orphan elements, nor any combination of

elements not connected to the rest of the business

model.

Figure 1: Apple iPod BM Canvas ©XPLANE 2008.

4.2 BM Mechanics

At the expert level, knowledge about the BMC and

the requirement to design a coherent model is well

incorporated into practice. The focus is on analyzing

the interaction of the model’s elements beyond the

relationships between them. It is not just about how

one element relates with its connected elements, but

about how they contribute to the overall thread of the

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

90

business model story. A chain of interactions must be

built from one element to another throughout their

relationship. To continue with our comparison with

other design domains, we move from architecture to

engineering, where it is not enough to just know about

the concept. An engineer needs to know about the

underlying physics that supports the concepts. For

example, it is not enough to know about the concepts

that make a plane; we also need to know about their

interactions. Without knowing how the aerodynamic

properties of a wing generate lift, it would be

impossible to design a plane that flies. Trial and error

with prototypes that are not based on physical

calculation would result in a large number of failures.

What’s more, the end result could not be explained

fully. Similarly, in the design of business models, the

activity has to move beyond prototyping and try to

simulate the model to see if it is “workable”. A good

business model needs to both do the right job and be

sustainable. Business model mechanics, outlines how

elements influence each other beyond their

relationship. The story can illustrate the flow of the

exchange value between customers and the product

and how it is produced. It is about understanding the

underlying interactions which make the business

model possible. In this context, explaining a revenue

stream can for example depend on a partner (a

relationship which is not defined in the basic

ontology). These connections can be drawn using

arrows at the top of the canvas to show the story.

Elements can also be added to the canvas one after

another while telling the story; this helps to

strengthen the illustration. Another way to highlight

the connectedness of elements is to use colors.

4.2.1 In Summary

At the expert level, the business model concepts of

the canvas are well understood, and analysis has

moved beyond the elements towards the interactions

based on their relationships. The business model is

coherent and does the right job. Above all, the

interactions needed to make it work are understood.

Thus, the model is the right one and has the potential

to be sustainable if implemented correctly.

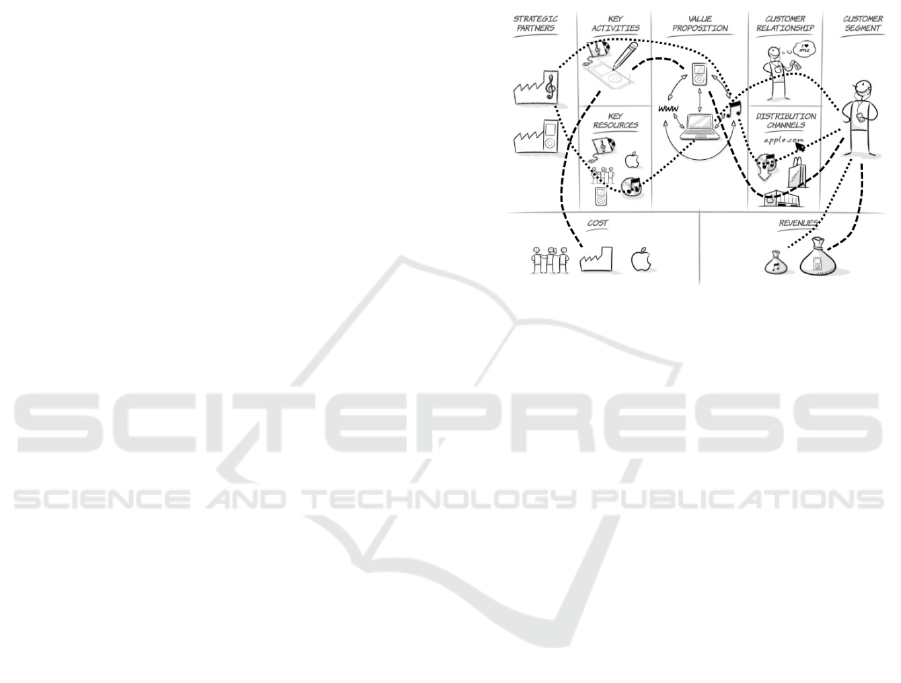

4.2.2 Apple iTunes BM Mechanics

In the case of the Apple iTunes, two stories can be

identified (see Figure 2): the music part (shown using

dotted lines), and the device (iPod) and brand part

(shown using dashed lines).

In order to make the platform attractive, Apple

had to offer a broad selection of titles, including all

the popular songs. This was achieved by making deals

with all the big majors. Skill and leverage were

required to be able to make deals which will make the

platform competitive on pricing and title selection.

Initially, to get the majors on board Apple added

Digital Rights Management (DRM) to protect the

digital music files; this had the side benefit of locking

the user in to Apple’s devices and software platform.

On the device side, functionality and esthetics had

to be combined in the design activity to create a

product which is in line with the customers’ brand

expectations.

Figure 2: Apple iPad BM Mechanics adapted from

©XPLANE 2008.

4.3 BM Evolution

At the master’s level, any considerations go beyond

the current business model. Masters are not afraid of

the unknown and are ready for anything. There is an

understanding that the strategy has to have a longer-

term vision that extends beyond the current business

model, and that to survive, it has to be able to evolve.

The focus is on actions that can be taken to evolve

from one business model to another. In order to be

aware of incoming changes, observation of the

business model’s environment is key. Our

architecture and engineering metaphor has its limits;

indeed, we would need to use analogies from the

realm of science fiction to illustrate transforming

behaviors. Therefore, a better analogy is the concept

of biological evolution. Individual business models

can become obsolete and die off; however, the

“species” evolves and survives through mutation and

selection. This means that in order to survive decay,

new business models (mutations from existing ones)

have to be tested continuously. When proven

successful, they are selected. Sometimes, the previous

business model might even be cannibalized by it.

A business model can do the right job and be

sustainable and still fail if it is not adapted to its

environment. Unlike our biology analogy, the

variations of a business model can be planned so that

it can be ready to adapt when the environment

changes. This involves planning different business

Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

91

models for a range of scenarios (Schoemaker, 1995)

and then being ready to switch to them depending on

the environment. The adaptability of a business

model to its context is key.

Various external occurrences may affect the

business model at any time; thus, different

alternatives need to be kept should one of them

become a reality. Keeping track of the mutation in

relation to external stimuli necessitates the

management of different versions of the business

model. The creation of multiple versions of a business

model to address different external environments is a

first step. Another step is to know how to adapt from

one version of a model to another. In this case, the

transformation between them needs to be highlighted.

For that purpose, we propose to use the concept of

transparent layers to stack business models parts on

top of each other. On paper this can be done with

tracing paper, each new layer can show new elements

and reuse of element which are visible in a semi-

translucent fashion from lower layers.

Together, the two steps allow us to evaluate a

model in the light of external factors, thus enabling us

to select the business model that fits best.

The combination of multiple transformation from

a given state help form a graph or a tree with branches

of possible evolution paths to follow for the future

business model. As well as to visualize the past

transformations which lead to the current state of the

business model.

4.3.1 In Summary

At the master’s level, business model concepts and

interactions (story) are well understood, both in terms

of a single model and the analysis of multiple models.

Decisions are made with the environment in mind in

order to deploy the right model in the right context.

Using this strategy, business models can be evolved

to adapt to any change.

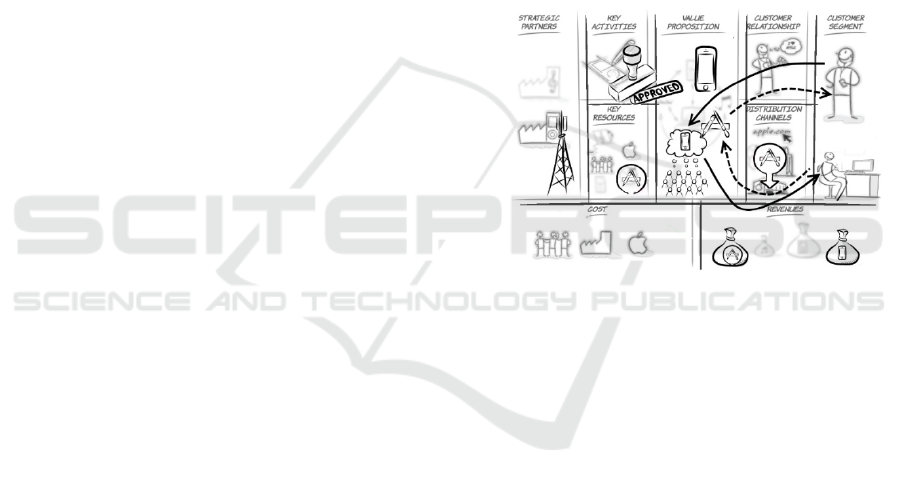

4.3.2 BM Evolution: From Apple iTunes to

Apple App Store Business Model

The transformation from a music service to a software

platform has many innovation drivers. A major one

which can be highlighted in Apple’s case was their

capability to create a touch-based screen for a phone

device by combining new external technology (touch

hardware) with internal knowledge of the design of

human friendly interfaces (custom software).

To create the App Store business model (seen in

Figure 3), Apple evolved their iTunes business model

by reusing existing components, expanding others

and adding new ones. Apple capitalized on its

knowledge of design, value chain management and

store to build and distribute a new touch based phone

(iPhone). New components included the extension of

the distribution channel to also include the new

partner, the mobile phone operators. Taking

advantage of their knowledge of building software

development kits for computers, Apple created a

development kit for the phone which is targeted at a

new customer segment of developers to create mobile

apps. To manage the quality of these apps and handle

financial transactions, a validation process and

revenue sharing model had to be put in place. Putting

these pieces into place helped to create an eco-system

that connects phone users in need of specialized apps

with a large developer community willing to provide

them for a small price. This transformation was much

more than a product innovation; rather, the whole

business model moved to a double sided business

model (Eisenmann, Parker, & Alstyne, 2006),

connecting the developers with the phone users.

Figure 3: Apple iTunes to App Store adapted from

©XPLANE 2008

.

5 EVALUATION

The first evaluation of the proposed concept is their

instantiation into cases. Being able to use the concept

to represent real world business models demonstrates

the validity of the artifact. The second part is to show

their utility having user employing the proposed

technics to represent their own business models.

Since the proposed concept are still very early ideas,

a further step would be to refine them. This would

allow for them, for example, to be implemented into

a computer-aided design tools for business models.

Providing advantages of automating some of the

concepts’ more tedious interactions such as validating

constraints, editing arrows paths and changing

visibility of elements.

For each of the BM concepts explained in the

previous section we present the goal solved by an

artefact we built to demonstrate its instantiation. We

give a summary of our related work findings and

propose some further possible evaluations.

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

92

5.1 BM Canvas Coherence

Goal: evaluate how rules can help beginner build

more coherent business models.

Useful validation questions and best practices

emerged during the years of teaching workshops on

the business model canvas. Some of which have been

formalized into guidelines and applied to build an

expository case business model (Fritscher and

Pigneur, 2014c). This could then be evaluated to see

how automated validation of the coherence of a

business model can assist the creation of better

business models. In the process of testing user

experience and idea generation differences between

paper and digital business model design, we also did

initial testing on coherence guidelines on paper with

a group of students. This showed that they lacked the

perseverance to rigorously apply them manually and

highlights the need to perform experiments with

computer aided systems.

5.2 BM Mechanics

Goal: evaluate how visual help such as color tagging

can help provide a clearer picture.

Drawing arrows on top of business models is also

something that emerges naturally in design session.

Therefore it is already somewhat in use although not

in a guided fashion. However, it is not always used as

described in the bm mechanics technique. Previous

work has shown that formalized links do not get

adopted by the users, instead color tagging of

elements can be used (Fritscher and Pigneur, 2014b).

We tested how tagging elements with different color

can help get a better visual picture without increasing

the visual legibility. This suggests that for

formalizing the BM mechanics feature, attention

should be focused on not making the arrow

interaction too constraining or complicated.

5.3 BM Evolution

Goal: Evaluate the usefulness of the layer concept to

represent business model transformations.

The business model evolution concept with its

two parts: transformation (mutation) and path of

possible (selection) is a somewhat complicated

concept. Especially to create the visual representation

on paper. Wanting to explore alternatives can lead to

a lot of copy work and stacking multiple versions of

transformation on top of each other can get visually

cluttered. An initial instantiation into a Computer

Aided Design (CAD) tool has been attempted and

1

Valve Corporation – Business Model Evolution Case

http://www.fritscher.ch/phd/valve/

shows promising results (Fritscher and Pigneur,

2014d). The creation of the prototype tool lead also to

the building of a case which describes a real world

business model evolution over seven transformations

and two business models evolving in parallel

1

. This

illustrate the potential of using a layered visual

approach to represent the dynamic nature of business

model evolution.

6 DISCUSSION

Although we presented the three concept separately,

each successive level of maturity builds on top of the

previous ones. A business model has to be coherent

in itself before exploring its dynamic aspect. The

prototype built to support BM evolution visualization

also supports drawing of arrows for BM mechanics.

This shows that the feature of drawing arrows

combines itself nicely with the layers that support the

transformations of the evolution. This combination

which provides means to decompose the internal

story into states that from a temporal segmentation of

the actions happening in the business model story.

This can then be visualized with layers as the

evolution of the story.

Implementing prototypes to support the concept

required to identify how the different design

technique can be support by CAD functions. We

summarize them in the next section.

Documenting the transformation which BMO

went through to get adopted by practitioners gave us

some insight into elements which made it possible.

We present our observation in the section entitled:

Lessons learned for business model methods

designers.

6.1 Design Techniques and Supporting

Cad Functions

In table 1 we provide a summary of the key design

techniques and supporting CAD functions for each

concept of the three maturity levels.

At the novice level, BM Canvas Coherence can be

improved by following guidelines. It is possible to

formalize these guidelines into verifiable rules. This

in turn allows to perform validation or trigger

contextual hinting assistance with a CAD tool. In

order for the tool to get a better model, it is needed to

indicate some of the elements relationship. This can

be accomplished by tagging them into different

colors, which is simpler for the user than explicitly

connecting them with links.

Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

93

At the expert level, BM mechanics helps to

provide a clearer picture on the internal interaction of

the business model. In order to support such

storytelling, functions like color and arrows can be

used on top of the BMC. In addition, a CAD tool can

help by toggling the visibility of elements as the story

progresses allowing for a dynamic representation of

another ways static canvas. This temporal execution

of the models’ story can then be tailored to the

individual stakeholders, the dynamic management of

the visibility allowing to support multiple stories on

the same canvas.

At the master level, BM Evolution helps to

address the transformation required by renovation

and exploration of possible future states envisioned

by scenario planning. Through layers, versioning and

by allowing to compute custom views of superposing

layers CAD tools offer dynamic visualization

showing any chosen past, present or future state of a

business model. Also by chaining the

transformations, it can be known which change

affects any descendant element’s future state. A new

computation of these updated views can be performed

by the tool without any work from the designer.

6.2 Lessons Learned for Business

Model Methods Designers

Based on the lessons gained from our experience we

can share the following observations on the possible

influences on the success of a business modeling

methods. These will help to broaden the adoption of

an academic enterprise ontology by practitioners:

Designing a method that can scale in complexity

for various proficiency levels, from novice to masters,

helps its adoption.

Performing design science evaluation cycles and

evolving the method after each evaluation is key to

identifying the right balance between simplification

and the re-addition of elements at different

proficiency levels.

Finding the right community is important: people

need to be willing to quickly test and iterate the

model’s concepts. (In our case, entrepreneurs were

the ideal test participants; it is in their nature to try out

business model concepts, which allowed for quick

iterations).

Providing a tool (free canvas and book) empowers

teaching at a university level as well as in workshops,

thus helping to spread the method.

7 CONCLUSION

Starting from observation on the evolution and

adoption of the BMC we identified the need to

address the issue of how to represent and help to

design the dynamic aspect of a business model

with the Business Model Canvas. Based on

observations we identified three maturity levels of

business model canvas design and addressed the issue

by splitting the question into three sub-questions:

How can the static design usage of the business

model canvas be improved (in relation to its

coherence)?

At the novice level, the simple nature of the

canvas helped in its adoption. This simplicity lends to

the use of building blocks as a checklist. It is however

necessary to keep in mind the relationship between

the elements in order to maintain the underlying

ontological nature of the business model theory.

Guidelines can help to verify these relationships and

thereby help to create more coherent models.

How to represent the dynamic aspect of

interactions happening inside the business model?

At the expert level, it is necessary to understand

the big picture. Showing a completed model to a

person for the first time would overload them with

information. Thus, design-thinking mechanics, such

as storytelling, have to be used to present the BM

mechanics of a model one step at a time. This allows

users to understand all the elements of a business

model, as well as the way they interact with each

other. These interactions can be further strengthened

by drawing arrows to outline the main story thread in

what we call BM Mechanics.

How to represent the transformation from one

state to another of a business model?

At the master level, it was found that making

different versions of a business model could help in

analyzing its reaction to the context. The management

of these versions quickly became a constraining

factor, particularly if only part of the business model

changed. Using layers to illustrate only the changes

is a design technique that helps to overcome some of

these constraints. Having the means to describe

transformation from one state into another, can then

be combined to form a chain of transformation

leading to a tree of possible path of evolution for the

business model in what we call the BM Evolution.

Table 1: Summary of concept, design technique and CAD functions.

Maturity Concept Design Technique CAD functions

Novice BM Canvas Coherence Guidelines, rules Colors, validation,

Expert BM Mechanics Storytelling Colors, arrows,

Master BM Evolution Renovation, what-if, scenario planning Layers, versioning,

Fifth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

94

To conclude, we provide several opportunities

that could be further investigated for each of the

discussed levels.

7.1 Opportunities

The business model ontology can be directly

extended in several ways. However, it is most

advantageous to capitalize on the diffusion and

knowledge of the current version. We argue that it is

helpful to develop extension as a plugin. For example,

a customer segment can be analyzed through the lens

of such tools as personas and customer insight or

through the framework of jobs to be done (Johnson,

2010). The current focus on plugins is mainly on the

value proposition and the customers, or the

connection between the two. There are many more

elements, however, that could benefit from in-depth

analysis at a component or relationship level.

Those that come to mind include categorizing the

channel based on the time and type of interaction of

the client-to-customer relationship for this particular

event; this would make better use of the customer

relationship component. Key activities can be

decomposed into types and supporting applications.

This allows us to better align the enterprise

architecture, its business processes and infrastructure

to the business model (Fritscher & Pigneur, 2015).

Beyond small transformation of business model,

research into a theory of evolution for business

models is of great interest, particularly in identifying

why some business models survive change better than

others.

REFERENCES

Blank, S. G. and Dorf, B. (2012). The startup owner’s

manual: the step-by-step guide for building a great

company. K&S Ranch, Incorporated.

Boland, R. J. and Collopy, F. (2004). Managing as

designing. Stanford University Press.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case

Study Research. The Academy of Management

Review, 14(4), 532.

Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., Alstyne, M. Van. (2006).

Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Business

Review.

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y. (2014b). Computer Aided

Business Model Design: Analysis of Key Features

Adopted by Users. Proceedings of the 47 Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

Computer Society Press (Ed.)

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y. (2014c). Business Model Design:

an Evaluation of Paper-Based and Computer-Aided

Canvases. Fourth International Symposium on (BMSD)

Business Modeling and Software Design. Scitepress

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y. (2014d). Visualizing Business

Model Evolution with the Business Model Canvas:

Concept and Tool. Published in Proc. 16th IEEE

Conference on Business Informatics (CBI’2014), IEEE

Computer Society Press

Fritscher, B., Pigneur, Y. (2015). A Visual Approach to

Business IT Alignment between Business Model and

Enterprise Architecture. IJISMD

Golnam, A., Ritala, P., Viswanathan, V., Wegmann, A.

(2012). Modeling Value Creation and Capture in

Service Systems. In Exploring Services Science (pp.

155–169). Springer.

Gordijn, J. and Akkermans, H. (2001). Designing and

Evaluating E-Business Models, (August), 11–17.

Gordijn, J., Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. (2005).

Comparing two business model ontologies for

designing e-business models and value constellations.

Proceedings of the 18th Bled eConference, Bled,

Slovenia, 6–8.

Gregor, S. and Hevner, A. (2013). Positioning and

Presenting Design Science Research for Maximum

Impact. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 337–355.

Gregor, S. and Jones, D. (2007). The anatomy of a design

theory. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 8(5), 312–335.

Johnson, M. W. (2010). Seizing the white space. Harvard

Business Press Boston.

McCarthy, W. (1982). The REA accounting model: A

generalized framework for accounting systems in a

shared data environment. Accounting Review.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2002). An eBusiness

model ontology for modeling eBusiness, 15th Bled

Electronic Commerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, June

17-19

Osterwalder, A. (2004). The Business Model Ontology-a

proposition in a design science approach. Academic

Dissertation, Universite de Lausanne, Ecole des Hautes

Etudes Commerciales.

Osterwalder, A. Pigneur, Y., Tucci C.L. (2005) "Clarifying

Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the

Concept," Communications of the Association for

Information Systems: Vol. 16

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model

generation : a handbook for visionaries, game changers,

and challengers. Wiley.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2013). Designing

Business Models and Similar Strategic Objects : The

Contribution of IS Designing. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 14(5), 237–244.

Schoemaker, P. (1995). Scenario planning: a tool for

strategic thinking. Sloan management review, 28(3)

Wegmann, A. (2003). On the Systemic Enterprise

Architecture Methodology (SEAM. Proceedings of the

5th International Conference on Enterprise Information

Systems, 483–490.

Weill, P. and Vitale, M. R. (2001). Place to space:

Migrating to eBusiness Models. Harvard Business

Press.

Extending the Business Model Canvas: A Dynamic Perspective

95