What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth

Systems to be Successfully Implemented?

Mansour Ahwidy

1,2

and Lyn Pemberton

1

1

University of Brighton, School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, Mithras housey, Lewes road, Brighton, U.K.

2

Keywords: Technology Readiness Assessment, Ehealth, Patient Electronic Health Records, Electronic Prescription.

Abstract: This piece of work provides an assessment of the readiness levels within both urban and rural hospitals and

clinics in Libya for the implementation of Ehealth systems. This then enabled the construction of a

framework for Ehealth implementation in the Libyan National Health Service (LNHS). The study assessed

how medications were prescribed, patients were referred, information communication technology (ICT) was

utilised in recording patient records, how healthcare staff were trained to use ICT and the ways in which

consultations were carried out by healthcare staff. The research was done in five rural healthcare institutions

and five urban healthcare institutions and focused on the readiness levels of the technology, social attitudes,

engagement levels and any other needs that were apparent (Jennett et al., 2010; Hasanain et al., 2014).

Collection of the data was carried out using a mixed method approach with qualitative interviews and

quantitative questionnaires (Molina et al., 2010; Creswell and Plano, 2010; Mason, 2006; Cathain, 2009;

Cathain et al. 2008). The study indicated that any IT equipment present was not being utilised for clinical

purposes and there was no evidence of any Ehealth technologies being employed. This implies that the

maturity level of the healthcare institutions studied was zero.

1 INTRODUCTION

When Ehealth systems are incorporated in

healthcare systems they can support them in

addressing the healthcare problems that are now

facing most countries within the developing world

(Kwankam, 2004; Ludwick and Doucette, 2009; Lau

et al., 2011). However, in order to introduce Ehealth

systems in developing countries there needs to be an

overhaul of the ICT systems being used there at

present and these calls for examinations of the

infrastructure, organisation and political situations in

these countries (Hossein, 2012). The research

carried out on transforming the LNHS has indicated

that a majority of Libyans do not have enough

access to the basics required for healthcare and most

people receive medical attention purely from the

LNHS. The LNHS has invested large amounts of

money in both urban and rural healthcare institutions

and services, along with ICT, in order that the

provision of healthcare services are improved by

healthcare staff having more efficient work

processes (Hamroush, 2014). However, although

there had been a large financial has been invested,

many healthcare staff have not benefitted from

improved ICT. This study looks at how Ehealth

systems can lead to healthcare professionals carrying

out their jobs more effectively and efficiently in the

LNHS. For achieving this, the researcher conducted

a study of urban and rural healthcare institutions in

order to assess their Ehealth readiness and to be able

to create an Ehealth framework for improving the

job processes of healthcare staff. The study looked at

ways in which Ehealth systems could be utilised for

improving the keeping of patient healthcare records,

making consultations, carrying out training, making

referrals and prescribing medication (Bilbey and

Lalani, 2013; Yellowlees, 2005; Broens et al., 2007;

Khoja et al., 2007). This study has lead to the

compilation of an Ehealth framework formulated

from the research data and it has formulated a list of

recommendations that can be utilised for the

transition from the present ICT levels in the LNHS

to a more complex and developed one where Ehealth

solutions can be integrated.

Ahwidy, M. and Pemberton, L.

What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth Systems to be Successfully Implemented?.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2016), pages 71-79

ISBN: 978-989-758-180-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

71

2 THE THEORY OF Ehealth

READINESS ASSESSMENTS

The theory of Ehealth Readiness Assessments was

carried out to define Ehealth systems, how they

might benefit a populace in a developing country

and how the readiness of that country might be

evaluated. There are many factors determining the

readiness of a country for the implementation of

Ehealth systems (Khoja et al., 2007; Jennett et al.,

2004), so it was a rewarding task to investigate the

findings of previous research. Using the Brighton

University data base, Science Direct, Google

Scholar, various Libyan data bases and existing

reports from hospitals in Libya, searches were made

for relevant articles about the implementation of

Ehealth systems in developing countries. Though

there were already assessments made of several

countries, none had yet been carried out in Libya.

This literature review will give some examples of

relevant research discovered during this search and

then expand on how these frameworks will be

utilised in this assessment on the readiness of Libya

for the implementation of Ehealth systems. There

was though a limited amount of formal articles on

this subject pertaining to developing countries, so a

search was made on many databases to find any

recent research carried out on assessing the readiness

of developing countries for Ehealth implementation.

Blaya et al, 2010 made a review of Ehealth

system that had been implemented in developing

nations. They found that if a system improved

communications between the healthcare institutions,

assisted in the management and ordering of

medications and helped in monitoring patients that

might abandon their care plan, then it could be

considered as ‘promising’. They found the systems

were effective at evaluating personal electronic

assistants and mobile apparatus as they improved the

collection of data in regards to quality and time

taken.

A majority of studies carried out to evaluate

Ehealth systems are made once the system has been

implemented, as seen in the example of

Ammenwerth et al. 2001. Alexander, 2007 points

out the importance of such studies for evaluating the

success of an Ehealth system, though Brender, 2006

points out the need for evaluations to take place

before the implementation of an Ehealth system in,

order to allow decisions to have a better sense of

direction. It is the advice of Brender, 2006 that the

researcher has heeded in the formulation of the

research question, tending toward the theory that a

readiness evaluation framework is needed before

implementing Ehealth systems (Yellowlees, 2005;

Broens et al., 2007; Khoja et al., 2007).

Li et al, 2010 cite four main areas to evaluate in a

study to assess readiness for implementing an

Ehealth system. Those areas are: if it is feasible;

does the organisation possess the necessary

resources, the risks involved; an assessment needs to

be made of what external factors might threaten the

project’s success, areas where problems may arise;

to identify weaknesses in the solution where risks

may occur and an assessment of how complete and

consistent the solution is.

3 METHODS

A mixed method approach was employed for

carrying out this research on healthcare institutions,

in both rural and urban areas of Libya (Figure 1)

(Molina et al., 2010; Creswell and Plano, 2010;

Mason, 2006; Cathain, 2009; Cathain et al. 2008),

employing both questionnaires and group

interviews. The data from the multi-case study was

analysed using the Cresswell framework (2007)

(Lynna et al., 2009). The formulation of the

interview questions and questionnaires was carried

out to make sure there was not anything missing by

seeing what was needed from the literature review

and the Chan framework (2010). The selection of the

healthcare institutions was done so that all the major

population centres of Libya were covered in five

primary areas.

3.1 Research Methods and Sample Size

For the purposes of this study the participants were

found in hospitals and clinics within the professions

of nursing, hospital administration, ward attendants

and doctors. The sample size (see Figure 1) of this

study was 165, with 138 of these returning a

questionnaire; as a percentage that worked out at

83.6%. Because 58 of the questionnaires were

excluded from the final total because they were

filled out incorrectly or superfluous, the final

number for analysis was 80 (N=80).

The questionnaire was divided into two sections,

with one set of questions aimed at general medical

staff, the other aimed at administration staff. The

questions for the medical staff were designed in

order to better understand of the work processes

involved in recording the healthcare data of patients,

carrying out referrals, consultations and

prescriptions. The questions for the administrative

staff were formulated in order to better understand

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

72

Figure 1: Sample size.

Table 1: Semi-structured interviews.

categories of

participants

Healthcare institution

Tripoli

Medical Centre

Al Razi Clinic

Benghazi

Medical Centre

Quiche Clinic

Sabha Medical

Centre

Al-Manshia

Clinic

Ibn Sina

Medical centre

Al- hyat Clinic

Zawia Medical

Centre

Al Bassatein

Clinic

Administrators 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 10

Doctors 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 10

Nurses 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 10

Ward assistants 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 10

Total of participants

40

of the present ICT infrastructure in the healthcare

institutions, the background history of the healthcare

institutions and the settings of the healthcare

institutions. The formulation of each question was

done using the Li et al, 2010 framework for

assessing Ehealth readiness.

Semi-structured interviews: A total of 40

individual actors (doctors, ward assistants,

administrators and nurses) were interviewed in

Arabic using semi-structured interview techniques

(Table 1). The durations of the interviews varied

between 20 and 40 minutes and averaged out at 30

minutes for each interview. The total time taken for

all the interviews was about 20 hours and the details

of these interviews are shown below in Table 1.

The reason for interviewing the staff at the

healthcare institutions was to find out what their

perceptions of Ehealth technologies were and how

useful and beneficial they would be if implemented

in the healthcare institutions where they worked.

4 RESULTS

The results of the data were separated into separate

sections based upon the Cresswell framework

(2007).

What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth Systems to be Successfully Implemented?

73

4.1 Results of the Questionnaire

4.1.1 Healthcare Staff Availability within

Urban and Rural Healthcare

Institutions

The results of the research showed that there was a

lack of doctors available to work in rural healthcare

institutions. The results indicated that the lack of

doctors in rural healthcare institutions meant that

doctors have much less time to spend treating

patients and often patients had more severe

symptoms as they had further to travel to receive

treatment and had consequently waited until their

condition worsened, whereas patients in urban areas

would seek treatment earlier as they lived closer to

healthcare institutions and had better transport

options available.

4.1.2 ICT Access in Urban and Rural

Healthcare Institutions

The study indicated that urban healthcare institutions

had more ICT equipment and more reliable internet

connections than those in rural areas. The rural

healthcare institutions had their internet connections

affected by bad phone lines and electrical power

supplies that were unreliable. Though the urban

healthcare institutions had more computers per

doctor than their rural counterparts, this was

academic as there were no computers present in the

rooms utilised by doctors for their consultations in

both rural and urban healthcare institutions,

indicating that doctors were not employing

computers to carry out consultations. Rather than

being used for medical purposes, it was ascertained

in the study that the computers in the healthcare

institutions were being utilised for administration

purposes. Though the study indicated that rural

medical staff were using computers more often than

in urban areas, this was only for personal use and

was not being carried out during their work time at

the healthcare institutions where they worked.

4.2 Results of the Group Interviews

Results of the group interviews were conducted by

using qualitative data analysis program called

NVIVO (Bazeley, 2007; Hamed and Alabri, 2013;

Ishak and Abu Bakar, 2012).

4.2.1 Access to Ehealth Solutions in Urban

and Rural Healthcare Institutions

The results of comparing access to Ehealth

solutions, in both rural and urban healthcare

institutions, indicated that there were not any

Ehealth solutions in any of the healthcare institutions

used in the case studies. The participants returned

positive feedback regarding the possible future

implementation of Ehealth solutions in the

healthcare institutions where they worked. It was felt

that the implementation of Ehealth technology

would improve the recording of patient healthcare

records, the treating of patients and the diagnosis of

patient's ailments. The results indicated that the

participants thought that the use of electronic patient

healthcare record systems would greatly improve the

service offered to patients and make the job easier

for staff and it would stop patients that attended

multiple healthcare institutions in order to get repeat

prescriptions of medication, therefore stopping fraud

occurring and saving the LNHS valuable resources.

Presently patient referrals are carried out by giving a

patient a handwritten referral on paper to take with

them to the healthcare institution to which they have

been referred. This meant referral letters were

getting lost or patients did not attend. Respondents

felt that this task being carried out electronically

would eliminate many of these problems.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Availability of Medical Staff in

Urban and Rural Healthcare

Institutions

The issue of physician shortages is far more pressing

in rural healthcare institutions than in urban

hospitals, though urban clinics do also experience

shortages.

The World Bank (2008), Jennett et al. (2005),

Campbell et al. (2001) , Blaya and Fraser (2010)

indicate that there are many challenges to providing

healthcare services in rural areas because of the

distances between populations that are dispersed and

isolated. Because of these challenges, in rural areas

there have often been problems in the recruitment of

staff and of them leaving to urban healthcare

institutions. In the LNHS, most of the skilled

healthcare staff choose to work in urban areas

(8280), whereas in rural areas staff are more

reluctant to relocate for work (3043) (Hamroush,

2014). A lot of rural areas do not have any

healthcare staff to provide healthcare to those that

require it, so the inhabitants have to travel long

distances to seek medical attention, particularly as

Libya is so big, yet so sparsely populated.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

74

The lack of healthcare staff in rural healthcare

institutions has to be the driving force for attracting

more money being invested in Ehealth solutions to

help healthcare staff to provide improved healthcare

using localised Ehealth frameworks that are

appropriate like the framework offered in this

research study. Hamroush (2014) compares the

availability of physicians in urban and rural

healthcare institutions in Libya.

Tables in Hamroush (2014) summarise the

average number of physicians that worked in the

rural healthcare institutions that were surveyed. The

Tables show that on average, there are

approximately 73% of physicians in Libya working

in urban healthcare institutions, compared to 26 %

physicians working in rural hospitals. Those

percentages indicate there are 20 physicians for

every ten thousand local inhabitants in Libya. The

following section will focus on how available and

accessible ICT technology is within the healthcare

institutions chosen for this study.

5.2 The Availability of ICT in Urban

and Rural Healthcare Institutions

The study outcomes showed that the availability of

ICT and internet connections in both rural and urban

healthcare institutions was insufficient for the

implementation of Ehealth solutions. In order to

function efficiently the ICT systems at each

healthcare institution need to be expanded and

integrated with other healthcare institutions.

Figure 2: Phases of Ehealth Maturity Curve.

6 EHEALTH MATURITY

DIAGRAM (EMD)

The study outcomes showed that when placed on an

Ehealth Maturity Curve (Van de Wetering and

Batenburg, 2009) the healthcare institutions in both

rural and urban areas were at level 0, as can be seen

below in Figure 2.

Figure 2 above shows that the urban and rural

healthcare institutions Ehealth solution levels are at

level 0. The healthcare institutions are able to send

emails to a central data storage facility for the

purpose of administration, but do not appear to use

this facility for medical purposes. Despite the

existence of some ICT in the healthcare institutions,

these systems are not used for contacting other

healthcare institutions. This is because of a lack of

equipment sometimes or bad internet connections

and electrical supplies, but is primarily due to the

technophobic attitudes of staff who feel unwilling to

embrace new forms of technology (Bain, and Rice,

2006-2007). Therefore, it is essential if these

healthcare institutions are to rise above level 0, a

Provincial Ehealth framework be formulated using

these findings to facilitate a plan for the future in

order for the healthcare institutions to move to level

2 on the Ehealth maturity curve. Because of this the

Provincial Ehealth framework was formulated, as

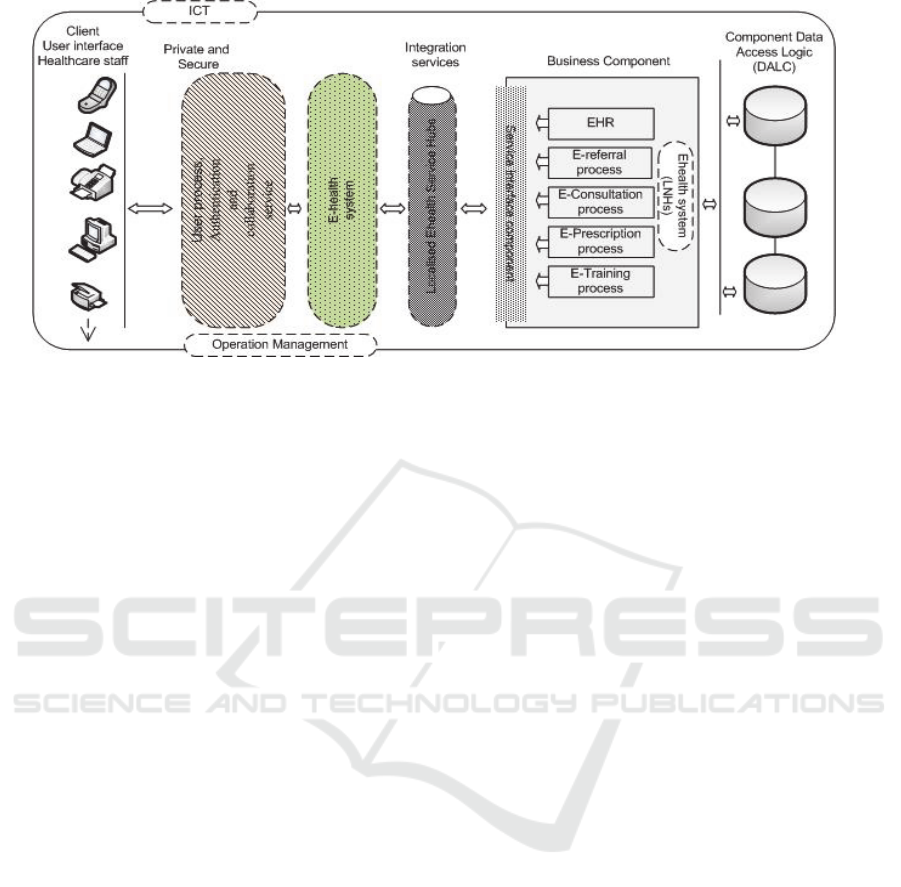

can be seen below in Figure 3.

The Provincial Ehealth framework architecture

highlights the need for the services offered in the

healthcare institutions to be integrated online by

using an Ehealth service hub that supports the whole

of the LNHS and for data to be stored electronically

rather than by using paper records as at present.

7 STRATEGY FOR EHEALTH IN

THE LNHS

In order for the LNHS to raise its maturity levels for

the implementation of Ehealth technology, it needs

to persuade LNHS staff and patients to adopt

Ehealth technologies. This can be carried out at a

local level throughout the LNHS, though this will

need to be orchestrated at a national level through

training, education and programmes to encourage

compliance and providing incentives.

The drive to raise the maturity levels for the

implementation of Ehealth technology throughout

the LNHS needs to focus in several areas. This is a

non exhaustive list of some of those:

1. LNHS users need to be made aware of what is

available to them through use of Ehealth in the

LNHS through media and other sources and be

shown the advantages of accessing their

individual healthcare records. Public support

for Ehealth developments will encourage

politicians to invest in developing ICT

What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth Systems to be Successfully Implemented?

75

Figure 3: Provincial Ehealth framework.

infrastructures and to ensure that broadband

speeds are sufficient and telephone connections

are reliable.

2. Healthcare institutions need to be given

financial aid with implementing Ehealth

systems to encourage their widespread usage.

There needs to be a direct link between usage

of Ehealth technology and funding.

3. It is of great importance for a healthcare system

utilising Ehealth technologies to ensure that

sufficient numbers of healthcare staff have

been trained to high enough standards to

operate the technology effectively. Staff also

need to be convinced of the need for Ehealth

technologies and be enthusiastic about the

prospect of being able to utilise it in order to

offer improved healthcare services

4. Researches carried out in other countries have

shown the Ehealth solutions that need to be

prioritised: sources of healthcare data, tools for

the delivery of services and the sharing of

electronic information.

5. The establishment of the foundation required

for exchanging data electronically throughout

the LNHS. This development is essential

because if it is not possible to exchange

healthcare data in a secure manner within the

LNHS there will be no Ehealth capabilities in

the LNHS.

6. Making sure that the LNHS Ehealth adoption

program is effectively coordinated, lead and

overseen. This will help establish the necessary

structures and mechanisms for governing

Ehealth solutions in the LNHS.

7. There needs to be a lot of money spent on

updating the IT infrastructure throughout the

LNHS as lack investment, coupled with

widespread civil war and looting, has left the

LNHS in short supply of basic computer

equipment.

8. Ehealth information stored by the LNHS needs

to be standardised throughout the LNHS in

order that information can be exchanged

effectively. This can be carried out through

central planning establishing implementation

procedures along with Ehealth implementation.

9. It is essential that the LNHS protects sensitive

healthcare data so that it remains private. In

order for this to succeed there needs to be a

robust and secure security system implemented

throughout the LNHS.

10. Healthcare information requires a regime for

identifying and authenticating information as

quickly as the LNHS can manage so that it can

be accessed and shared securely.

11. Facilitating healthcare institutions in the

establishment of ICT that are appropriate for

their individual needs.

12. Coordinating healthcare institutions to create

ICT infrastructures that are sustainable.

13. Supporting healthcare institutions to connect to

a nationwide fibre optic network for sharing

data and connecting to other healthcare

institutions.

14. Implementing policies for the exchange of

information between healthcare institutions that

do not contravene any privacy laws.

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

76

15. Implementing E-learning for improving

education levels.

16. The construction of the Ehealth capabilities of

the LNHS incrementally and pragmatically,

while initially investing in Ehealth

technologies that will afford the most benefits

to users of the LNHS.

17. Provide help to those areas of the LNHS that

require it, but not at the expensive of those that

would like to develop at a faster pace.

18. Creating processes for EHRs, E-consultations,

E-prescriptions, E-referrals and E-training

systems;

8 THE STUDY’S LIMITATIONS

The largest challenge in carrying out this case study

for the researcher was not just the large distances

between healthcare institutions that were travelled,

in order to create as balanced a reflection as possible

of opinions in the LNHS, but the state of warfare

that existed in the country at the time between rival

tribal factions.

The other limitation in this study is that the

framework has not been used in practice to see

where it does not work, so that it can be improved.

This is because it would require a lot of money to

test it that is not currently available in Libya, though

when the researcher presented his findings to experts

in Libya it was received positively.

A lot of the limitations inherent in the research

technique and methodology have already been

covered in the writings above. Further factors

affecting the efficiency of the research were the time

limitations imposed by the LNHS and the Libyan

culture itself. The reason for employing the methods

of questionnaire and interview in this study was to

enhance the level of confidentiality that the

participants would enjoy. That a high level of

privacy was maintained was of utmost importance.

Another hurdle placed in the researcher’s way in

carrying out the interviews was that of gender.

Because of the restrictions within Libyan culture

regarding the mixing of males and females, the

researcher being male needed to employ females to

carry out such tasks. It was expected that by placing

guarantees of anonymity the participants would

therefore feel more relaxed and deliver answers that

were more accurate, confidential and honest. Time

presented a serious limitation to the researcher due

to healthcare institutions allowing interviews to be

for no longer than 25 minutes. This was because the

LNHS authorities did not want the medical staff’s

private time intruded upon, hence limiting interview

time to that reserved for giving lectures, thus placing

a limitation upon the quantity of variables that could

be harvested.

The fact that the participant’s confidential details

were self reported creates yet another limitation to

the study. This is because it may create inaccuracies,

thus information that is technologically, socially,

culturally or medically influenced, may need to be

considered as differing somewhat to reality when

medical ISs are being planned.

9 CONCLUSIONS

After having reviewed the available literature on

Ehealth technology, assessing the healthcare

institutions selected for Ehealth readiness and

analysing the results, this paper will now set out the

conclusions reached by the researcher, namely that:

all the healthcare institutions were at level 0 on the

Ehealth maturity curve and their ICT infrastructures

would need integrating so that medical staff could

communicate within their healthcare institutions and

with other healthcare institutions, therefore

benefitting from Ehealth solutions that might be

implemented at some future date. The researcher

therefore concludes that, for the successful

implementation of Ehealth systems into the LNHS,

the ICT infrastructures within the healthcare

institutions of the LNHS need to be interconnected

so that E-consultations can be carried out to aid

medical staff in treating patients more efficiently

when they do not have the training for a specific

condition, but can source this information from a

colleague in another healthcare institution. The

researcher also came to the conclusion that all the

various systems and patient healthcare data need to

become interoperable and brought together into an

efficient and effective system. To conclude, this

paper has laid out a provisional Ehealth framework

that, if followed, will lead to the healthcare

institutions of the LNHS moving from level 0 on the

Ehealth maturity curve to a level 2, thus enabling

healthcare staff to provide improved levels of

healthcare to their patients.

REFERENCES

Ammenwerth E., Eichstadter R., Haux R., Pohl U., Rebel

S. and Ziegler S. (2001). A randomized evaluation

of a computer-based nursing documentation

What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth Systems to be Successfully Implemented?

77

system, Methods Inf Med 40, pp. 61–68.

Alexander H. (2007). Health service evaluations: Should

we expect the results to change practice? Evaluation,

9(4), 405-414.

Bain, C.D., and Rice, M.L. (2006-2007). The Influence of

Gender on Attitudes, Perception, and use of

Technology. Journal of Research on Technologyin

Education, 39(2), 119- 132.

Bazeley, P. (2007). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo.

(p6-15) London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Bilbey, N. and Lalani, S. (2013). Canadian Health Care:

A Focus on Rural Medicine. aVancouver Fraser

Medical Program 2013, UBC Faculty of Medicine,

Vancouver, BC. UBCMJ. issue 2(2).

Blaya, J. and Fraser, H. F. (2010). Implementing Medical

Information Systems in Developing Countries, What

Works and What Doesn’t. AMIA 2010 Symposium

Proceedings Page – 232.

Brender J. (2006). Evaluation Methods for Health

Informatics. Elsevier Inc. London, UK.

Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating Quantitative and

Qualitative Research: How is it Done?, Qualitative

Research, Vol. 6, pp 97-113.

Bryman, A. (2007). Barriers to Integrating Quantitative

and Qualitative Research, Journal of Mixed Methods

Research, Vol. 1, pp 8-22.

Broens, T., Huis in’t Veld, R.M.H.A., Vollenbroek-

Hutten, M.M.R., Hermens, H.J., Van Halteren,

A.T. & Niewenhuis, L.J.M. (2007). Determinants of

successful telemedicine implementations, Journal of

Telemedicine and Telecare, 6(13), 303- 309.

Cathain, A. (2009). Mixed Methods Research in the

Health Sciences. A Quiet Revolution, Journal of

Mixed Methods Research, Vol. 3, pp 3-6.

Cathain, A., Murphy, E. and Nicholl, J. (2008). The

Quality of mixed Methods Studies in Health Services

research, Journal of Health Services Research &

Policy, Vol 13, No 2, 2008: 92–98: The Royal Society

of Medicine Press Ltd 2008.

Campbell J.D., Harris K.D. and Hodge R. (2001).

Introducing telemedicine technology to Rural

Physicians and settings, J Fam Pract; 50:419-24.

Creswell, J. and Plano Clark, V. (2010). Designing and

Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd Edition,

Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Connie V. Chan , David R. Kaufman (2010) A technology

Selection Framework for Supporting Delivery of

Patient-Oriented Health Interventions in Developing

Countries. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 43

(2010) 300–306.

Hasanain, R., Vallmuur, K., and Clark, M. (2014).

Progress and Challengesin the implementation of

electronic medical records in Saudi Arabia: A

systematic review. Health Informatics- An

International Journal (HIIJ) Vol.3, No.2, May 2014.

Hamed, H. AlY. and Alabri, S. (2013). Using NVIVO for

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research. Ministry of

Education, Sultanate of Oman. International

Interdisciplinary Journal of Education – January

2013, Volume 2, Issue 2.

Hamroush, F. (2014). Medical Studies & Training:

Challenges and Opportunities. Minister Of Health in

the Transitional Libyan Government, Libya Higher

Education Forum 2014, London.

Hossein, S. M. (2012). Consideration the Relationship

between ICT and Ehealth. International Institute for

Science, Technology & Education. Vol 2, No 8.

Ishak, N. M. and Abu Bakar, A. Y. (2012). Qualitative

Data Management and Analysis uSing NVivo:An

approach used to Examine Leadership Qualities

Among Student Leaders. Education Research Journal

Vol 2.(3) pp. 94-103, March 2012, International

Research Journals.

Jennett P., Yeo M., Pauls M. and Graham J. (2004).

Organizational readiness for telemedicine:

implications for success and failure. J Telemed

Telecare. 9 Suppl 2: S27-30.

Jennett P., Jackson A., Ho K., Healy T., Kazanjian A.,

Woollard R. et al. (2005). The Essence of Telehealth

Readiness in Rural Communities: an Organizational

Perspective. Telemed J E Health: 11:137-45.

Jennett, P., Gagnon, M. & Brandstadt, H. (2010).

Readiness Models for Rural Telehealth, Journal of

Postgraduate Medicine, 51(4), 279-283.

Khoja S., Scott R., Ishaq A. and Mohsin M. (2007).

Testing Reliability of eHealth Readiness Assessment

Tools For Developing Countries. ehealth international

journal, Volume 3(1).

Khoja, S., Scott, R., Casebeer, A., Mohsin, M., Ishaq, A.

& Gilani, S. (2007). e-Health readiness assessment

tools for healthcare institutions in developing

countries, Telemedicine and e-Health, 13(4), 425-432.

Kwankam, S. (2004). What e-Health can offer?, World

Health Organization: Bulletin of the World Health

Organization, 82(10): 800-802.

Lau, F., Price, M. and Keshavjee, K. (2011). From Benefit

Evaluation to Clinical Adoption: making Sense of

Health Information System Success in Canada.

Electronic Healthcare, Vol. 9, No.4.

Li, J. (2010). E-health readiness framework from

electronic health records perspective. Australia.

Ludwick, DA., Doucette, J. (2009). Adopting Electronic

Medical Records in Primary Care: Lessons Learned

from Health Information Systems Implementation

experience in seven countries. Int J Med Inform 78:

22–31.

Lynna, J., Martens, J. , Washington, E., Steele, D. and

Washburn, E. ( 2009). A cross Case Analysis of

Gender issues in Desktop Virtual Reality Learning

environment. Volume 46. Number 3. Oklahoma State

University.

Mason, J. (2006). Mixing Methods in a Qualitatively

Driven Way, Qualitative Research, Vol. 6, pp 9-25.

Molina Azorín,J, M and Cameron, R. (2010). The

Application of Mixed Methods in Organisational

Research: A Literature Review. The Electronic

Journal of Business Research Methods, Volume 8,

Issue 2 2010 (pp.95-105).

Niglas, K. (2004). The Combined Use of Qualitative and

Quantitative Methods in Educational Research

Tallinn

ICT4AWE 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

78

Pedagogical University Press, Tallinn.

Nouh, M. H. and Jagannadha, R. P. (2013). Post-operative

Antibiotic Usage at Benghazi Medical Center, Libya

between 2009 and 2012. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy

and Biological Sciences (IOSR-JPBS). Volume 8,

Issue 4, PP 57-60.

Van de Wetering, R. & Batenburg, R. (2009). A PACS

maturity model: A systematic meta-analytic review on

maturation and evolvability of PACS in the hospital

enterprise, International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 78, 127-140.

Yellowlees, P. (2005). Successfully developing a

telemedicine system, Journal of Telemedicine and

Telecare, 11(7), 331-336.

Wong, L. P. (2008). Data Analysis in Qualitative

Research: a Brief Guide to Using Nvivo. Malaysian

Family Physician 3(1).

World Health Organization (WHO). (2008). Developing

Health Management Information Systems: A Practical

Guide for Developing Countries. Geneva: World

Health Organization.

What Changes Need to be Made within the LNHS for Ehealth Systems to be Successfully Implemented?

79