Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

Noel Carroll

1,2

, Marie Travers

2

and Ita Richardson

1,2

1

ARCH, Centre for Applied Research in Connected Health, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

2

Lero, The Irish Software Engineering Research Centre, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Keywords: Connected Health, Evaluation, Framework, Information Systems, Management.

Abstract: Connected Health is an emerging model of care that engages technology to improve patient care and

(re)habilitation. It encourages self-efficacy by developing client-centred care pathways and evidence-based

interventions to reduce the need for hospital-led care and empower patients in their homes. It also promotes

improved ‘connectivity’ between healthcare stakeholders by means of timely sharing and presentation of

accurate and pertinent information about patient status. Connected Health initiatives can achieve this

through smarter use of data, devices, communication platforms and people. However, there are few efforts

which have established an evaluation model to encapsulate and assess the value and potential impact of

Connected Health solutions from multiple stakeholders’ perspectives. We examined information systems

(IS) and health information systems (HIS) literature to identify whether a model could apply to Connected

Health. However, many of the evaluation models are narrow in focus but have influenced our development

of the Connected Health Evaluation Framework (CHEF). CHEF offers a generic approach which

encapsulates a holistic view of a Connected Health evaluation process. It focuses on four key domains: end-

user perception, business growth, quality management and healthcare practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

Societal and demographic changes, coupled with

economic challenges, have driven the need for us to

reconsider how we deliver health and social care in

our community (Rodrigues et al., 2012). Healthcare

places considerable financial burdens on both public

purse and personal finance. In addition, due to

demographical shifts, there is a growing demand for

care to be delivered in a more personalised context,

delivering ‘smart’ solutions via technological

devices. Connected Health is an emerging and

rapidly developing field which has the potential to

transform healthcare service systems by increasing

its safety, quality and overall efficiency.

While considered a disruptive technological

approach in healthcare, Connected Health is used by

different industries in various sector contexts (for

example, healthcare, social care and the wellness

sector). Thus, various definitions exist with different

emphasis placed on healthcare, business, technology

and support service providers, or any combination of

these.

Within the research community, Connected

Health is not well defined and remains an

ambiguous concept. The ECHAlliance (2014) group

promote the concept of Connected Health to act as

“the umbrella description covering digital health,

eHealth, mHealth, telecare, telehealth and

telemedicine”. In addition, Caulfield and Donnelly

(2013) defines of Connected Health as “a conceptual

model for health management where devices,

services or interventions are designed around the

patient’s needs, and health related data is shared, in

such a way that the patient can receive care in the

most proactive and efficient manner possible”. The

key here is the connectedness and the manner in

which technological solutions enable healthcare

solutions. In addition, the FDA (2014) describes

Connected Health as “electronic methods of health

care delivery that allow users to deliver and receive

care outside of traditional health care settings.

Examples include mobile medical apps, medical

device data systems, software, and wireless

technology”. Thus, as technological solutions seek

to enable new healthcare relationships and

partnerships, there is a growing interest in

examining information and communications

technology (ICT) to support the development of

Connected Health. Connected Health has been

defined by Richardson (2015) as “patient-centred

Carroll, N., Travers, M. and Richardson, I.

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem.

DOI: 10.5220/0005623300170027

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 17-27

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

17

care resulting from process-driven health care

delivery undertaken by healthcare professionals,

patients and/or carers who are supported by the use

of technology (software and/or hardware)”.

Therefore Connected Health can be considered to be

a socio-technical healthcare model which extends

healthcare services beyond healthcare institutions.

We capture this in the term ‘ecosystem’. A

Connected Health Ecosystem implies that we to

strike a balance between the various requirements

and dynamics associated with different stakeholder

groups in a modern healthcare sector. For example,

this can include primary care, secondary care,

payers, policy makers, pharmacies, clinicians,

patients, family members, innovators, public

officials, patient groups, academics and

entrepreneurs collaborating to experiment, develop

protocols and tests, and evaluate new Connected

Health service solutions.

As technological solutions seek to enable such

connectivity between healthcare stakeholders

(Hebert and Korabek, 2004), there is a growing

interest in examining how Information and

Communication Technology (ICT) enables

Connected Health solutions. If health technology is

not designed, developed, implemented, maintained,

or used properly, it can pose risks to patients.

Therefore, a continuous evaluation lifecycle is

critical for various stages of the service lifecycle.

However, healthcare technology, such as the case

with Connected Health, lags behind in presenting

evidence-based evaluation on the contribution of

ICT in supporting healthcare services (for example,

Heathfield et al., 1998; Fineout-Overholt et al.,

2005; Misuraca et al., 2013; Tuffaha et al., 2014).

This paper offers an overview of some of the key

evaluation frameworks in e-health and information

systems (IS) and investigates how these can

contribute towards the evaluation of Connected

Health. Bridging these efforts, we propose a

Connected Health Evaluation Framework (CHEF).

CHEF also plays on the fact that we need to evaluate

all of the ‘ingredients’ before we can learn of the

potential impact of Connected Health technology.

2 OBJECTIVE & APPROACH

Connected Health is emerging as a solution which

offers significant promise in how healthcare can

deliver accessible care with improved safety and

patient outcomes. Connected Health encompasses

terms such as wireless, digital, electronic, mobile,

and tele-health and refers to a conceptual model for

health management where devices, services or

interventions are designed around the patient’s

needs.

Considering the emerging nature of Connected

Health, there are few attempts to develop evaluation

frameworks to guide how to investigate the impact

of Connected Health technologies. To address this

gap, we formulate the following research question:

Which technology evaluation models can support

the evaluation of Connected Health solutions?

To explore this question, we undertook a

literature review with a particular emphasis on

information systems (IS) and healthcare IS (HIS)

evaluation literature.

3 IS & HIS EVALUATION

MODELS

The process of evaluation serves a number of

fundamental objectives. Within a healthcare context,

evaluating the impact of IS is important to

understand the dynamic nature of technology and its

ability to improve clinical performance, patient care,

and service operations (Meltsner, 2012). Therefore,

evaluation offers us the ability to learn from past and

present performance (Friedman and Wyatt, 1997)

with a view to improving process, care (Leveille et

al., 2012), economics (Dávalos et al., 2009; Van

Ooteghem et al., 2012) and healthcare satisfaction

for the future (Kuhn and Giuse, 2001; Van Bemmel

and Musen, 1997).

Identifying various methods of evaluation

throughout the IS literature enables us to build on

the current knowledge and identify techniques to

improve healthcare systems (Yusof et al., 2006)

which support the emergence and evidence-base of

Connected Health innovation. We build on the work

of O’Leary et al., (2015) in adopting a generic

approach to untangle the complexity of evaluating

Connected Health innovation.

There have been several well-cited evaluation

models across the IS and healthcare field which we

can examine with a view of developing a Connected

Health Evaluation Framework (CHEF). Various

evaluation approaches on IS were developed with

different outlooks including technical, sociological,

economic, human and organisational. A number of

frameworks also explicitly focus on HIS evaluation.

Our selection criteria were based on the search

for information system evaluation models which

adopts multiple perspectives of assessment. We

discovered that many of the models were too narrow

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

18

Table 1: Summary of IS Evaluation Frameworks.

Framework Clinical Technical Economic Human Organisational Regulation

4Cs Model

CHEATS Model

TEAM

ITAM

IS Success Model

TAM

HOT-fit Model

Integrated Model

RATER Model

Search Engine

Success Model

in focus and only address a specific element of

information systems which would not be suitable for

the generic nature of Connected Health. We

summarise these perspectives as follows:

Clinical: medical practice, based on observation,

interaction and treatment of patients;

Technical: the application of hardware and

software devices to connect healthcare service

operations in a more efficient manner;

Economic: understanding the processes that

govern the production, distribution and

consumption of goods and services which impact

on healthcare;

Human: training, personnel attitudes,

ergonomics and regulations affecting

employment and patient experience in

healthcare. This can also examine the evolution

of social behaviour and development through the

influence of both internal (e.g. attitudes, emotion,

or health status) and external factors (e.g. service

availability or economics of care);

Organisational: the nature of the healthcare

organisation, its structure, culture and politics

affect an evaluation;

Regulation: a mechanism to sustain and focus

control which is often exercised by a public

agency over activities that are valued by the

healthcare community and its stakeholders.

We examine these key factors in a number of

HIS and IS evaluation models and summarise their

primary focus in Table 1.

Table 1 examines various factors which are

considered in evaluation ranging from clinical,

technical, economic, human, organisation and

regulation. This indicates that there is a lack of a

holistic evaluation approach on healthcare which

must be addressed in Connected Health to deliver

innovative and perhaps ‘disruptive’ solutions

(Christensen et al., 2000; Schwamm, 2014). There

have been some efforts to evaluate HIS including

clinical decision support systems.

3.1 HOT-fit Model

Yosof et al., (2006) proposed the Human,

Organization and Technology-fit (HOT-fit

framework) which was developed from a literature

review on HIS evaluation studies. A review of the

literature revealed that while specific instances of

the evaluation of healthcare technology exists

(Mathur et al., 2007; O’Neill et al., 2012), there is no

evidence of a generic evaluation model which can be

applied to Connected Health to provide a holistic

view of its potential impact.

3.2 4Cs Model

The 4Cs Evaluation Framework steers away from

the technical issues of evaluation and using a social

interactionist perspective, it examines how human,

organisational and social issues are important for

service design, development and deployment. The

4Cs framework examines issues associated with

communication, care, control, and context based on

medical informatics (Kaplan, 1997; Kaplan, 2001).

3.3 CHEATS Model

Another model which evaluates the use of ICT in

healthcare includes the CHEATS framework (Shaw,

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

19

2002). It evaluates healthcare through six core areas:

Clinical: focusing on issues such as quality of

care, diagnosis reliability, impact and continuity

of care, technology acceptance, practice changes

and cultural changes;

Human and Organisational: focusing on issues

such as the effects of change on the individual

and on the organisation;

Educational: focusing on issues such as

recruitment and retention of staff and training;

Administrative: focusing on issues such as

convenience, change and cost associated with

health system;

Technical and Social: focusing on issues such

as efficacy and effectiveness of new systems and

the appropriateness of technology, usability,

training and reliability of healthcare technology.

3.4 Team

Another model which evaluates HIS is the Total

Evaluation and Acceptance Methodology (TEAM).

This offers an approach based on systemic and

model theories (Grant et al., 2002) and identifies

three key IS evaluation dimensions in biomedicine:

Role: evaluates IS from the designer,

specialist user, end user and stakeholder

perspective;

Time: identifies four main phases which

provide relative stability of the IS;

Structure: distinguishes between strategic,

tactical or organisational and operational

levels.

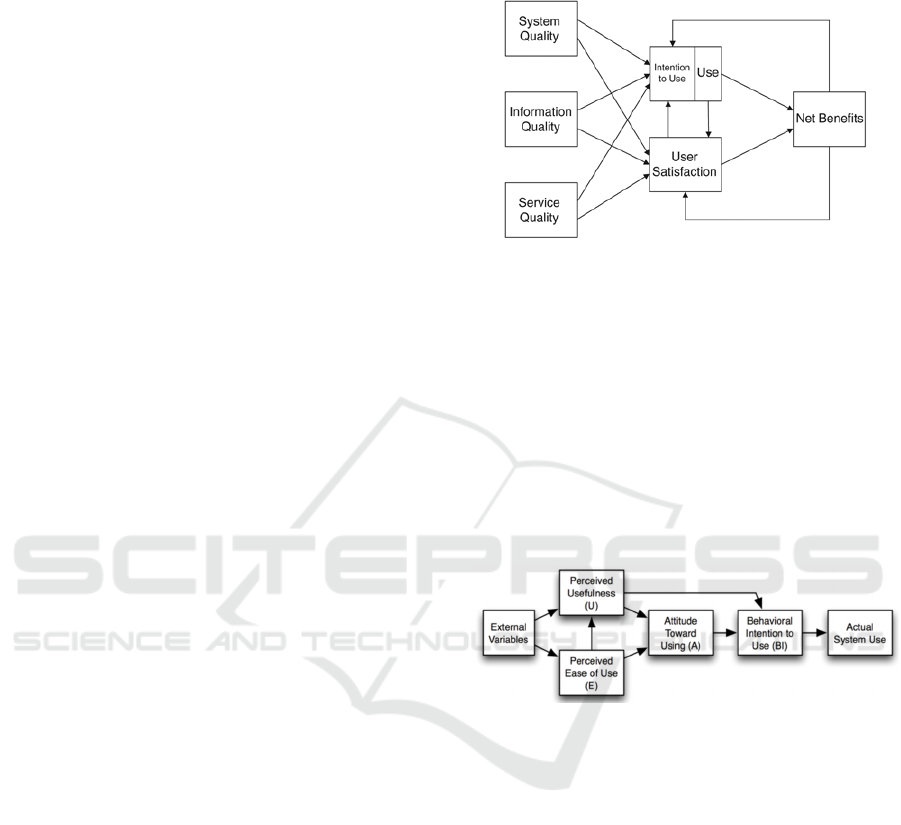

3.5 IS Success Model

From an Information Systems (IS) perspective, there

are also several well cited evaluation frameworks

which we examined. For example, the IS Success

Model (DeLone and McLean, 1992; Delone and

McLean, 2003) examines the success of IS from a

number of different perspectives and classifies them

into six categories of success (DeLone and McLean,

2003). The model adopts a multidimensional

framework which measures independencies between

the various categories (Figure 1):

Information

System and service quality

Use (intention to)

User satisfaction

Net benefits

These dimensions suggest that there is a clear

relationship between the six categories and

influences the success of the IS (i.e. net benefits).

The net benefits influence user satisfaction and use

of the information system.

Figure 1: IS Success Model (DeLone and McLean, 2003).

3.6 Tam

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

examines how users accept the use of technology

though a number of important influential factors

(Davis, 1989). Among these factors are (see Figure

2):

The perceived usefulness (U) of the

technology;

The perceived ease-of use (E) of the

technology.

Figure 2: Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989).

TAM suggests that these factors determine

people’s intention to use a technology. While TAM

provides an excellent approach to examining

people’s acceptance of technology, it is limited in

explanatory terms (Gregor, 2006) of technological

‘value’.

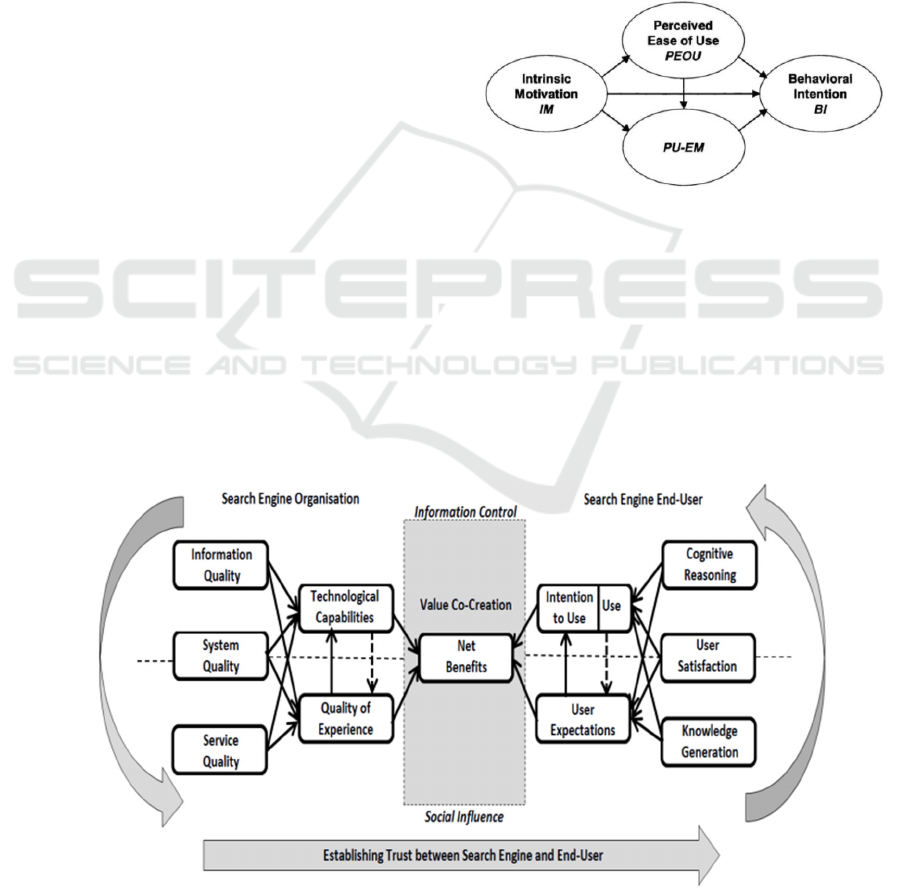

3.7 Search Engine Success Model

In a similar vein, Carroll (2014) extends the IS

Success Model to develop the Search Engine

Success Model and examines the complex task of

evaluating the impact of search engine technology

on users. The independencies between the

components build upon Delone and McLean IS

Success Model but include a more comprehensive

view of the value co-creation relationship between

the organisation and end-user. From a Connected

Health perspective, this model illustrates the cyclical

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

20

nature of establishing trust to generate and sustain

net benefits. The model adopts a multidimensional

framework which measures independencies between

the various categories (Figure 3):

Information

System and service quality

Use (intention to)

Technological capabilities

Quality of experience

User expectation

User satisfaction

Cognitive reasoning

Knowledge generation

Net benefits through a co-creation relationship

3.8 ITAM

Adopting a similar outlook on technology

evaluation, Dixon (1999) presents a socio-technical

evaluation model which examines the behavioural

aspects of technology using the IT Adoption Model

(ITAM). ITAM provides a framework for using

implementation strategies and evaluation techniques

from an end-user’s perspective (i.e. fit for purpose,

user perceptions of innovation usefulness and ease

of use, and adoption and utilisation). Related

research also focuses on consumer health behaviours

and their adoption of medical technologies. For

example, Wilson and Lankton (2004) examines

consumer acceptance of HIS to support patients in

managing manage chronic disease.

3.9 Integrated Model

Wilson and Lankton (2004) integrated the use of

TAM to extend the model which became known as

the Integrated Model (Figure 4). Their Model

merges the perception of technology’s usefulness

(PU) with extrinsic motivation (EM) in a PU-EM

scale and perception of a technology’s ease of use

(PEOU) scales. The key factors of this model

evaluate healthcare technology by examining the:

Perception of a technology’s usefulness (PU);

Perception of a technology’s ease of use

(PEOU);

Behavioural intention (BI) to use the

technology;

Intrinsic motivation (IM);

Extrinsic motivation (EM) to determine BI.

Figure 3: Integrated Model (Wilson and Lankton, 2004).

The five dimensions identified using the

Integrated Model can also provide a useful lens to

understand the impact of technology in Connected

Health, particularly the influential factors on IT-

enabled innovation and the adoption of solutions.

Identifying gaps in health service sectors is

important to enhance the overall quality of the

service delivery and identify how Connected Health

solutions can address these gaps.

Figure 4: Search Engine Success Model (Carroll, 2014).

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

21

3.10 RATER Model

There are a number of methods which evaluate the

quality of services with a view of identifying areas

to prioritise service improvements. For example, the

RATER Model (Zeithaml et al., 1990) offers a

simplified version of the SERVQUAL model

(Parasuraman et al., 1988) using five key customer

service issues (Table 2). They focus on five

dimensions to analyse and improve service

offerings. The five key dimensions can also support

the development of a service plan to improve service

delivery and are particularly apt in Connected Health

solutions.

Table 2: Key Dimensions within the RATER Model.

Dimension Description

Reliability

Ability to provide dependable service,

consistently, accurately, and on-time.

Assurance

The competence of staff to apply their

expertise to inspire trust and confidence.

Tangibles

Physical appearance or public image of a

service, including offices, equipment,

employees, and the communication material.

Empathy

Relationship between employees and

customers and the ability to provide a caring

and personalised service.

Responsiveness

Willingness to provide a timely, high quality

service to meet customers needs.

3.11 Intervention Mapping

Other initiatives which may support the evaluation

of Connected Health solutions include the

Intervention Mapping Framework (IMF). The IMF

provides a systematic and rigorous approach that can

be used to develop and promote health programmes.

It achieves this through developing theory-based and

evidence-based health promotion initiatives. These

initiatives may be incorporated into a Connected

Health evaluation, particularly from a patient-

focused perspective.

3.12 Research Gap

From our literature review, we can conclude that

evaluating the value of HIS is a complex task. This

is also confirmed by a recent report on ‘The Value of

Health Information Technology: Filling the

Knowledge Gap’ (Rudin et al., 2014) which draws

similar conclusions in that the majority of evaluation

articles are limited. They state that evaluation

articles use “incomplete measures of value and fail

to report the important contextual and

implementation characteristics that would allow for

an adequate understanding of how the study results

were achieved”, and provide a conceptual

framework using three key principles for measuring

the value of healthcare IT as follows:

Value includes both costs and benefits;

Value accrues over time;

Value depends on which stakeholder’s

perspective is used.

These principles suggest that a core focus of an

evaluation strategy ought to focus on ‘value’ and

how this can be represented from various

stakeholders’ perspectives. Other models discussed

above referred to this as ‘net benefits’ or ‘value co-

creation’. In summary, while the frameworks

explored in this report evaluate various aspects of

HIS and IS they do not provide a holistic view of

healthcare technology and cannot be successfully

applied to support the board nature of Connected

Health.

With the aim of developing a more universally

adoptable framework for multiple perspectives of

Connected Health, we propose the Connected Health

Evaluation Framework (CHEF). The need for such

an approach was also highlighted by Rudin et al.,

(2014) who raise concerns regarding evaluation in

healthcare: “unfortunately, we have found that few

studies include both costs and benefits in their

definitions of value. Most studies look at only short-

term time horizons, which ignore many of the

downstream benefits of the HIT, and many studies

don’t even explicitly state to whom the value is

accruing.” We set out to address this gap using

CHEF.

4 CHEF

This section presents the Connected Health

Evaluation Framework (CHEF). The development of

CHEF (Figure 5) is influenced by both the strengths

of current HIS/IS models and the limitations of these

models which emerged from the literature review. In

addition, while economics and regulation often

shape innovation, both have been largely overlooked

in many of the evaluation models we identified.

‘Healthcare net benefits’ are presented at the core of

CHEF. CHEF is comprised of four main layers for

Connected Health, broadly addressing clinical,

business, users and systems with a view to determine

how these co-create value. Each of the categories

supports specific Connected Health operations

across all service lifecycle stages, ultimately

generating healthcare net benefits. For example:

Business Growth: as part of the overall

healthcare service strategy phase, this focuses on

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

22

Figure 5: Connected Health Evaluation Framework (CHEF).

driving change and economics in healthcare and

organisational market share. Particular emphasis

on evaluation focuses on the cultural and strategy

change for introduction Connected Health

innovations. While introducing Connected Health

innovation, an economic evaluation should be

undertaken to examine the potential profits and

costs associated its implementation.

Healthcare Practice: as part of both the

healthcare service design and transition phases,

this focuses on health IT and innovation and how

it alters practice/clinical pathways (O’Leary et al.,

2014). From a technological perspective, an

evaluation is carried out on both the hardware and

software capability to deliver a Connected Health

solution. In addition, the innovativeness of

altering healthcare practice is evaluated from a

socio-technical and ethnography viewpoint. This

allows the examination of the impact of delivering

information in a new format and whether it

enhances the overall connectivity of healthcare

stakeholders.

End-user Perception: as part of both the

healthcare service transition and operations

phases, this focuses on safety and quality of

healthcare innovation for a user’s perspective (e.g.

a doctor, a patient or carer). This phase evaluates

the safety and quality of Connected Health

solutions. From a safety viewpoint, an evaluation

may be carried out on the usability and level of

empowerment a solution may provide in order to

provide a balance in empowerment and safety.

From a quality viewpoint, we can evaluate

whether Connected Health technologies have led

to improved healthcare decision-making and

enhanced usefulness of technological innovations.

Quality Management: as part of both the

healthcare service operations and continuous

service improvement phases, quality management

focuses on technical and regulation requirements

and conformity assessment. This phase can

evaluate the requirements of healthcare

stakeholders to generate awareness of Connected

Health innovation and to support users through

improved training programmes. In addition, an

evaluation may also assess the organisation’s

conformity with medical device regulations in

terms of technology classification and compliance.

This also informs how an organisation can realign

their service strategy – and the service lifecycle

continues through a continuous improvement

philosophy.

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

23

Within each of these subcategories, we will

identify key metrics (Rojas and Gagnon, 2008)

associated with the evaluation of Connected Health

solutions. As part of our future work, we will

identify operational key metrics for each category

and its components to support Connected Health

innovation. The outer layer of CHEF comprises of

various service lifecycle stages and highlights the

need to identify value points in each of the service

lifecycle phases.

The service lifecycle phases play a critical role

in aligning the service development process and the

market opportunities (Figure 6). The Connected

Health environment addresses healthcare technology

requirements to enhance the level of healthcare

service offerings. Connected Health can potentially

address unfulfilled needs in healthcare as a result of

external forces and various demographic drivers.

Many of these drivers are also opening new market

opportunities which enable Connected Health

solutions to improve healthcare service maturity

through enhanced service performance. The value of

Connected Health solutions includes an improved

quality of experience and usefulness in technological

solutions to deliver healthcare.

While acknowledging that technology can

provide healthcare solutions, it is equally important

to question at each phase of the service lifecycle, for

example “what problem does information solve?”

(Postman, 1992) and “what is the problem to which

this technology is a solution?” (Postman, 1999).

Postman’s question applies equally well to the

Connected Health field as a basic evaluation

question. Building on this, it is critical that as a

starting point, and before we can successfully

identify value in Connected Health, the current

healthcare system is modelled, for example, actor

interaction, value stream mapping, resource

exchange, service bottlenecks, workflows,

organisational structures and mapping the healthcare

solutions market landscape.

CHEF offers an approach to guide the evaluation

process. Thus, the two key aspects as we move

forward in Connected Health evaluation can be

derived in:

Ensuring the systems, devices and services meet

the health and social needs of users through

evidence-based research;

Developing innovative patient-centred

technological solutions to empower people to

effectively manage their health and wellness in the

home and community (Delbanco et al. 2012).

In addition, from a Connected Health

perspective, evaluation must be conducted to assess

its impact across the broad spectrum of care

services. The scope of CHEF explicitly

acknowledges the broad scope and existence of

different stakeholders. CHEF will facilitate

evaluations through an assessment process designed

to provide:

A holistic view of a healthcare system;

Tailored analysis of healthcare service

lifecycle;

Performance metrics on service operations and

patient-focused analytics;

Scorecard and benchmark tools to assess

Figure 6: Connected Health Environment.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

24

healthcare technological integrations,

healthcare interventions and healthcare

providers.

These will also form part of our research strategy

in our quest to develop a CHEF and apply it to

various healthcare products and services and derive

core evaluation metrics. There is a clear correlation

between Connected Health functionality and

healthcare net benefits from multiple perspectives.

CHEF will be further validated through continued

industry engagement and Connected Health

technologies to accommodate the rapid growth of

healthcare IT solutions.

CHEF can also promote innovation by guiding

evaluation at all stages of the health IT product

lifecycle and encouraging organisations to consider

the complex socio-technical ecosystem in which

healthcare products are developed, implemented,

and used. Particular interests include the quality

systems in place to govern Connected Health data

management, access to clinical information,

stakeholder communication, knowledge

management and patient privacy. Regulations and

conformity assessment supports the technology

evaluation processes from a health and safety

perspective. We believe that CHEF will also support

organisation in examining potential risks posed by

Connected Health functionality and in comparing

them to the potential net benefits, for example,

developing a benefit-risk profile. In addition, by

meeting the regulatory evaluation of a medical

device, conformity assessment will evaluate whether

they present challenges to Connected Health

innovation. Combined, CHEF promotes the need to

incorporate Connected Health evaluation at various

stages using quality management principles, adopt

continuously revised standards and harness a

learning and continual improvement environment to

improve patient safety.

CHEF will enable organisations to identify

poorly designed healthcare solutions, assess

performance requirements, monitor human

interaction (end-user) and identify potential gaps

within a business strategy. In addition, CHEF offers

a first step towards employing evaluation to extend

the evidence-based foundation for Connected Health

through the assessment of best practice and by

identifying interventions and opportunities for

improvement based on the CHEF evaluation and

evidence gathered.

5 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

With significantly greater shifts in demographics

and longevity, the cost of healthcare will show a

corresponding increase. In an attempt to reduce

these growing costs, governments typically attempt

to reduce healthcare overheads, including staffing,

patient contact time, consultation and scheduling

various appointments. This can also create service

bottlenecks which jeopardises the quality and safety

of healthcare.

There is evidence that a paradigm shift to

empower people to take more control of their own

health is occurring. Technology innovation enables

and aligns with these healthcare shifts, providing

greater service efficiencies and effectiveness and

supporting the reduction of costs. Connected Health

presents an exciting approach towards redesigned

healthcare delivery. However, the success of

Connected Health will hinge on evaluation strategies

to determine the real value or benefits (healthcare,

quality of care, economics, etc.) associated with

technological integration in healthcare service

systems. This paper presents an overview of how

existing evaluation frameworks in e-health and

information systems can they influence Connected

Health evaluations.

Bridging these efforts, we propose the CHEF

which we will employ through industry engagement.

Throughout our evaluation research, we also

discovered that that concept of connectedness

through IT-enabled healthcare is a complex socio-

technical environment which is also impacted on

various geography, socio-economic status, and

technological competence – often influencing their

attitudes to Connected Health innovation.

Technology therefore plays a key role in fostering

healthcare relationships given healthcare

stakeholders a sense of being interconnected.

Through evaluation processes, if we can develop a

better understanding of the Connected Health

network structure, we can begin to further evaluate

the impact of IT innovation on a healthcare

ecosystem.

CHEF is a first step in offering a holistic view of

Connected Health and is a step towards an

evaluation of healthcare technological innovations.

As part of our future work, we will continue to

collaborate with industry and academic members

within ARCH - Applied Research for Connected

Health Technology Centre. Through our

multidisciplinary research team, we will extend this

work and validate CHEF with various healthcare

stakeholders and IT providers.

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

25

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by ARCH -

Applied Research for Connected Health Technology

Centre (www.arch.ie), an initiative jointly funded by

Enterprise Ireland and the IDA, SFI Lero Grant

(www.lero.ie) 13/RC/2094 and Science Foundation

Ireland (SFI) Industry Fellowship Grant Number

14/IF/2530.

REFERENCES

Carroll, N. (2014). In Search We Trust: Exploring How

Search Engines are Shaping Society. International

Journal of Knowledge Society Research (IJKSR),

5(1), 12-27.

Caulfield, B. M., and Donnelly, S. C. (2013). What is

Connected Health and why will it change your

practice?. QJM, hct114.

Christensen, C. M., Bohmer, R., and Kenagy, J. (2000).

Will disruptive innovations cure health care?. Harvard

business review, 78(5), 102-112.

Dansky, K.H., Palmer, L., Shea, D., Bowles, K.H. (2001).

“Cost Analysis of Telehomecare”. Telemedicine

Journal and e-Health. September, pp. 225-232.

Dávalos, M.E., French, M.T., Burdick, A.E., Simmons,

S.C. (2009). “Economic Evaluation of Telemedicine:

Review of the Literature and Research Guidelines for

Benefit–Cost Analysis”. Telemedicine and e-Health,

December, pp. 933-948.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease

of use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS Quarterly, pp. 319-340.

Delbanco, T., Walker, J., Bell, S. K., Darer, J. D., Elmore,

J. G., Farag, N., Feldman, H.J., Mejilla, R., Ngo, L.,

Ralston, J.D., Ross, S.E. Trivedi, N., Vodicka, E.,

Leveille, S.G. (2012). Inviting patients to read their

doctors' notes: a quasi-experimental study and a look

ahead. Annals of internal medicine, 157(7), 461-470.

Delone, W. H. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of

information systems success: a ten-year update.

Journal of management information systems, 19(4), 9-

30.

DeLone, W. H., and McLean, E. R. (1992). Information

systems success: the quest for the dependent variable.

Information systems research, 3(1), 60-95.

Department of Communications, Energy and Natural

Resources (2011). Knowledge Society Strategy:

Report on e-Health Developments in Ireland.

Retrieved on 02/02/2015 from Website:

http://tinyurl.com/lrs3aja.

Dixon, D. R. (1999). The behavioral side of information

technology. International journal of medical

informatics, 56(1), 117-123.

ECHAlliance (2014). Connected Health – White Paper.

Retrieved on 09/03/2015 from Website:

http://cht.oulu.fi/uploads/2/3/7/4/23746055/connected

_health.pdf.

Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, B. M., and Schultz, A.

(2005). Transforming health care from the inside out:

advancing evidence-based practice in the 21st century.

Journal of Professional Nursing, 21(6), 335-344.

Friedman, C. P., Wyatt, J.C. (1997). Evaluation Methods

in Medical Informatics. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Grant, A., Plante, I., and Leblanc, F. (2002). The TEAM

methodology for the evaluation of information

systems in biomedicine. Computers in Biology and

Medicine, 32(3), 195-207.

Gregor, S. (2006). The nature of theory in information

systems. MIS Quarterly, 30(3), pp. 611-642.

Heathfield, H., Pitty, D., and Hanka, R. (1998). Evaluating

information technology in health care: barriers and

challenges. BMJ, 316(7149), 1959.

Hebert, M.A, and Korabek, B. (2004). “Stakeholder

Readiness for Telehomecare: Implications for

Implementation”. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health.

March, pp. 85-92.

Kaplan B. (1997). Addressing organizational issues into

the evaluation of medical systems. J Am Med Inform

Assoc.; 4(2): 94-101.

Kaplan, B. (2001). Evaluating informatics applications—

some alternative approaches: theory, social

interactionism, and call for methodological pluralism.

International journal of medical informatics, 64(1), 39-

56.

Kuhn, K. A., Giuse, D.A. (2001). "From Hospital

Information Systems to Health Information Systems -

Problems, Challenges, Perspective," Yearbook of

Medical Informatics, 63-76.

Leveille, S. G., Walker, J., Ralston, J. D., Ross, S. E.,

Elmore, J. G., and Delbanco, T. (2012). Evaluating the

impact of patients' online access to doctors' visit notes:

designing and executing the OpenNotes project. BMC

medical informatics and decision making, 12(1), 32.

Mathur, A., Kvedar, J.C. and Watson, A.J. (2007).

“Connected health: A new framework for evaluation

of communication technology use in care

improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes,” Current

Diabetes Reviews, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 229–234.

Meltsner, M. (2012). A patient's view of OpenNotes.

Annals of internal medicine, 157(7), 523-524.

Misuraca, G., Codagnone, C., and Rossel, P. (2013). From

practice to theory and back to practice: Reflexivity in

measurement and evaluation for evidence-based policy

making in the information society. Government

Information Quarterly, 30, S68-S82.

O’Leary, P., Carroll, N., and Richardson, I. (2014). The

Practitioner's Perspective on Clinical Pathway Support

Systems. In Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), 2014 IEEE

International Conference on (pp. 194-201). IEEE.

O’Leary, P., Carroll, N., Clarke, P. and Richardson, I.

(2015). Untangling the Complexity of Connected

Health Evaluations, IEEE International Conference on

Healthcare Informatics 2015 (ICHI 2015) Dallas,

Texas, USA, October 21-23.

O’Neill, S.A., Nugent, C.D., Donnelly, M.P., McCullagh,

P., and McLaughlin, J. (2012). Evaluation of

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

26

connected health technology,” Technology and Health

Care, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 151–167.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., and Berry, L. L. (1988).

Servqual. Journal of retailing, 64(1), 12-40.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture

to technology. New York: Vintage Press.

Postman, N. (1999). Building a Bridge to the 18th

Century: How the Past Can Improve Our Future. New

York: Alfred A. Knopf Publishers.

Richardson, I. (2015). Connected Health: People,

Technology and Processes, Lero-TR-2015-03, Lero

Technical Report Series, University of Limerick.

Rodrigues, R., Huber, M., and Lamura, G. (2012). Facts

and figures on healthy ageing and long-term care.

Itävalta: European Centre for Social and Welfare

policy and Research: Vienna.

Rojas, S. V., and Gagnon, M. P. (2008). A systematic

review of the key indicators for assessing

telehomecare cost-effectiveness. Telemedicine and e-

Health, 14(9), 896-904.

Rudin, R.S., Jones, S.S., Shekelle, P., Hillestad, R.J. and

Keeler, E.B. (2014). The Value of Health Information

Technology: Filling the Knowledge Gap. The

American Journal of Managed Care, Special Issue:

Health Information Technology, Vol. 20, No. SP 17.

Schwamm, L. H. (2014). Telehealth: Seven Strategies To

Successfully Implement Disruptive Technology And

Transform Health Care. Health Affairs, 33(2), 200-

206.

Shaw, N. T. (2002). ‘CHEATS’: a generic information

communication technology (ICT) evaluation

framework. Computers in biology and medicine,

32(3), 209-220.

Tuffaha, H. W., Gordon, L. G., and Scuffham, P. A.

(2014). Value of information analysis in healthcare: a

review of principles and applications. Journal of

medical economics, 17(6), 377-383.

Van Bemmel, J.H. and Musen, M.A. (1997). Handbook of

Medical Informatics. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.

Van Ooteghem, J., Ackaert, A., Verbrugge, S., Colle, D.,

Pickavet, M., and Demeester, P. (2012). Economic

viability of eCare solutions. In Electronic Healthcare

(pp. 159-166). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Wilson, E. V., and Lankton, N. K. (2004).

Interdisciplinary Research and Publication

Opportunites in Information Systems and Health Care.

The Communications of the Association for

Information Systems, 14(1), 51.

Yusof, M. M., Paul, R. J., and Stergioulas, L. K. (2006).

Towards a framework for health information systems

evaluation. In System Sciences, HICSS'06.

Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International

Conference on (Vol. 5, pp. 95a-95a). IEEE.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., and Berry, L. L. (1990).

Delivering quality service: Balancing customer

perceptions and expectations. Simon and ssSchuster.

Evaluating Multiple Perspectives of a Connected Health Ecosystem

27